A Customized Machine Learning Model for Improving Malware Detection

Автор: Mosleh M. Abualhaj, Sumaya Al-Khatib, Mahran Al-Zyoud, Mohammad O. Hiari, Ali Al-Allawee, Mohammad A. Alsharaiah

Журнал: International Journal of Computer Network and Information Security @ijcnis

Статья в выпуске: 1 vol.18, 2026 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Malware detection is a significant factor in establishing effective cybersecurity in the face of constantly increasing cyber threats. This research article aims to investigate the field of machine learning (ML) techniques for malware detection. More specifically, the paper focuses on the Customized K-Nearest Neighbors (C-KNN) classifier and the Firefly Algorithm (FA). The work aims to assess the effectiveness of C-KNN and C-KNN with FA (C-KNN/FA) in malware identification using the MalMem-2022 dataset. The novelty of the proposed method lies in the synergistic integration of the C-KNN algorithm with the FA for metaheuristic optimization. The use of FA to select the most relevant features enables the C-KNN to train on a small and high-quality feature set. Therefore, the performance of malware detection will be improved. We compare the performance of both methods to understand the influence of KNN parameter adjustment and feature selection on malware classification. The C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have produced remarkable results in malware identification, reaching an accuracy of 99.98%. This accomplishment is quite encouraging. With regard to multiclass and binary classification methods, C-KNN and C-KNN/FA both perform better than their alternatives.

Cybersecurity, Malware, Machine Learning, K-nearest Neighbors, Firefly Algorithm

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15020172

IDR: 15020172 | DOI: 10.5815/ijcnis.2026.01.01

Текст научной статьи A Customized Machine Learning Model for Improving Malware Detection

Cyber-attacks pose critical cybersecurity concerns globally, and detecting malicious hackers before an attack can save high financial costs and prevent devastating consequences. Data breaches in companies cost tens of millions. Hackers continually evolve tools to acquire confidential information and exploit vulnerabilities in an organization's security [1]. One avenue they exploit is through malware, often capitalizing on a company's "Bring-Your-Own-Device" (BYOD) policy. This policy permits employees to access confidential company information using their mobile devices, providing hackers with a broad attack surface to inject malware into the company's infrastructure [2].

Malware incidents have surged since 2018, with 5.5 billion attacks, a 2% year-over-year increase. As of 2023, 300,000 new cases of malware were created daily, taking an average of 49 days to identify. Hackers are now developing advanced malware to penetrate systems and avoid detection [3]. This advanced malware can self-replicate, insert itself into programs or files, and even lay dormant. It can simulate sandbox conditions to bypass malware detection mechanisms by making the software believe the file is safe [4].

Malware detection employs various approaches, including signature-based methods that rely on known malware patterns, heuristic analysis to identify suspicious behaviors, anomaly detection by comparing against normal system behavior, sandboxing for dynamic analysis of malware samples, and Machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence for pattern recognition and anomaly detection, and memory analysis for runtime inspection. A combination of these approaches is often necessary for comprehensive and effective malware detection in the constantly evolving landscape of cybersecurity threats [4-7].

To combat advanced malware, organizations turn to Advanced Malware Protection (AMP), primarily designed to prevent breaches caused by sophisticated malware. ML models, a key component of AMP, identify patterns matching known malware characteristics, offering a more effective defense against zero-day attacks and sophisticated threats [6,8,9]. While ML enhances malware detection rates and efficiency, it faces challenges, requiring substantial data to build accurate algorithms. However, the data fed to ML models may contain redundant and irrelevant variables, impacting performance by increasing over-fitting, degrading accuracy, and extending training time. ML feature selection algorithms, such as metaheuristic algorithms, address these issues. These algorithms randomize and select optimal solutions, improving optimization performance [10,11].

Firefly Algorithm (FA), a widely used metaheuristic algorithm in cybersecurity, is employed in this paper for feature selection to improve accuracy in malware exposure. Leveraging FA's unique characteristics, the goal is to strategically enhance the efficiency and success of feature selection for malware detection scenarios [12,13]. After feature selection, the proposed model utilizes KNN to classify malware from non-malicious files, with tailored KNN parameters optimized for malware detection. Particularly, this work will employ FA and KNN to handle the issue of the malware that is concealed in memory and is used to abuse the weaknesses in MS Windows [14,15].

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the related works. Section 3 discusses the MalMem-2022 dataset. Section 4 presents the key elements and steps of the suggested AMD system. Section 5 shows the environment in which the suggested AMD system is developed, along with the AMD achieved results. Finally, the paper concludes.

2. Related Works

This section analyses numerous preceding works that have been suggested to tackle the problem of malware exposure. The analyzed works are separated into three categories. The first category analyses the accomplishment of numerous methods on various datasets. The second category focuses on achieving the KNN classifier (the classifier used in this work) to detect malware with multiple datasets. Finally, the third category analyses the works that have been assessed utilizing the MalMem-2022 dataset (the dataset that has been utilized in this study).

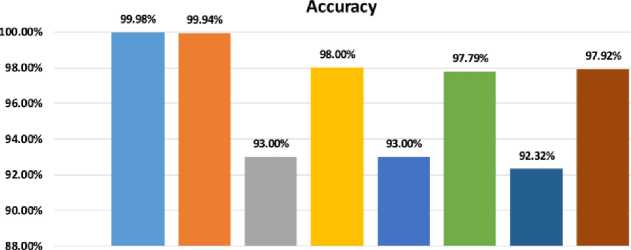

The first category discusses the attainment of numerous methods on multiple datasets. Rakshit et al. [16] suggested a technique to find the structural characteristics that ML systems can use to detect ransomware. The research employs a modified version of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), called Attended Recent Inputs (ARI)-LSTM. The empirical analysis showed that the ARI-LSTM outperforms traditional LSTM in ransomware detection. Meanwhile, the ARI-LSTM achieved an impressive 93% accuracy in ransomware detection. Odat E. et al. [17] suggested an ML model for malware detection based on the coexistence of static features. The approach suggests malicious applications possess distinct co-existing permissions and APIs compared to benign ones. By utilizing the coexistence of characteristics, the model successfully classifies malware with high accuracy when assessed using a variety of conventional ML algorithms. On the Malgenome dataset, the suggested technique attains an accuracy of almost 98%, compared to 87% for the state-of-the-art. On the Drebin dataset, the suggested technique attains an accuracy of about 95%, outperforming the state-of-the-art accuracy of approximately 93%. Zhang S. et al. [18] present an ML model to distinguish domain generation algorithms (DGA) to mitigate potential malware threats. To predict future domain features, the model applies a timeseries method that relies on a Hidden Markov Model (HMM). A deep neural network (DNN) model is also incorporated to handle the vast dataset collected over time. The proposed framework and DNN model demonstrated high performance, with classification accuracy reaching 95.89%, the DNN model achieving 97.79%, second-level clustering at 92.45%, and HMM prediction at 95.21%. Danial et al. [19] present a new method that focuses on specific forms of spyware and ransomware, including screen recorders, keyloggers, and blockers. The proposed method delineates the foundational architecture of an anti-spyware program designed to detect spyware activities by tracing their paths, terminating running processes, removing executable files, and restricting network connections. The experiments exhibited an accuracy rate of around 93% in identifying spyware. Almashhadani et al. [20] address the problem of hostbased detection techniques that demand host infection to detect abnormalities and identify ransomware. With the use of TCP, HTTP, DNS, and NBNS traffic, eighteen features were retrieved. These features are instructive and can distinguish traffic produced by a compromised host. The proposed technique operates at both the packet and flow levels. Extensive experimental investigations confirm the efficacy of the derived characteristics with a high detection accuracy of 97.92% for packet level and 97.08% for flow level. Kento et al. [21] have proposed a method for detecting malware infections focusing on registry accesses and malicious processes executed on Windows-based host PCs. In experimental tests conducted using URSNIF banking spyware, the authors calculated a high failure rate in registry accesses and confirmed the detection results through specific access checks. This method was applied to eight instances of URSNIF, revealing a registry access failure rate of approximately 35.3% and identifying six specific registry accesses.

The second category focuses on achieving the KNN classifier (the classifier used in this work) in detecting malware with different datasets. Akhtar et al. [22] proposed a method for dynamic malware analysis using the Cuckoo sandbox. The Cuckoo sandbox observes malware behavior within a controlled environment and produces a report detailing its actions. The proposed method includes a module for extracting and selecting features. The module extracts the important features from the report to ensure high malware classification accuracy. Several ML algorithms were employed for malware classification in the proposed method. The proposed method achieved 98.69% accuracy with the KNN classifier. Gumaa M. A. [23] proposed a method for malware detection based on the most important permissions and API calls. The proposed method focuses on selecting and generating features through a graph-based approach. It combines two types of raw features to create a new, more informative set of features. The features are then used to train the ML classifiers, including KNN. The experimental results showed that the KNN classifier has attained an accuracy of 96.5% in malware detection. S. Poornima et al. [24] proposed an automated hybrid analysis method for malware detection. The malware data is fed to the feature extraction process and classified into signature- and behavior-based data. The resulting features are used with many algorithms to evaluate malware classification accuracy. Among several classifiers, the KNN classifier achieved an accuracy of 97.78% in malware classification. Radwan, A.M. [25] proposed a method to classify the portable executable (PE) file in Windows OS as normal or malicious. The proposed method extracted several raw features, using a static analysis technique, from the three main headers of PE files. The extracted features are combined with a set of derived features to form an integrated feature set. Most of the common ML classifiers are used to classify the PE files OS as normal or malicious based on the resulting integrated feature set. The KNN classifier has achieved a remarkable accuracy of 98.70% in distinguishing the malicious from the normal PE files. Akhtar M.S. et al. [26] have proposed a method that detects polymorphic malware using ML classifiers. The features were inspected and classified within the proposed method as dynamic and static. The features that significantly impacted the results were kept, and the remaining features were eliminated from the set of features. The feature rank method selects the significant features for malware detection. The results show that the KNN classifier has achieved 95.02% accuracy in malware detection with the proposed method. Alkahtani H. et al. [27] have proposed a method to detect malware on smartphones. The proposed method extracts static and dynamic features from the smartphone's unknown applications. The extracted features classify these unknown applications as malicious or benign. Several ML classifiers were used with the proposed method to detect malicious applications based on the extracted features. The KNN classifier has achieved an accuracy of 90% in detecting malicious applications.

The third category analyses the works that have been assessed utilizing the MalMem-2022 dataset (the dataset that has been utilized in this study). Luhr J. et al. [28] have suggested and compared two techniques to detect the malware that is concealed in the memory of the computers. The first method employs a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) framework, and the second one employs an ML ensemble-based model of SVM, LR, KNN, and RF classifiers. The two methods were compared utilizing the MalMem-2022 dataset in multiclass and binary classification. The MLP technique attains 99.93% and 75.91% accuracy in multiclass and binary classification, respectively. On the other hand, the Ensemble method achieves higher accuracy of 99.95% and 79.11% than the MLP technique in multiclass and binary classification, respectively. Carrier et al. [29] proposed another method to detect malware and evaluated it on the MalMem-2022 dataset. The suggested technique employs a two-layer ensemble learning framework: the first layer includes NB, DT, and RF as base learners, while the second layer uses LR as the meta-learner. This combination achieved the highest accuracy, reaching 99%. Mezina et al. [30] suggested a malware detection technique, which they evaluated using the CIC-Malmem-2022 dataset. The suggested technique employs four layers of a dilated convolutional network (DCNN). The four layers contain two convolutional layers, each with 32 to 256 neurons. The proposed method achieved 99% and 83% accuracy with multiclass and binary classification, respectively. Jerbi et al. [31] suggested another technique that employs the Malmem-2022 dataset for assessment. The proposed technique uses a memetic algorithm to produce new instances of malware. Then, the new samples are identified utilizing efficient detectors generated by a method that relies on artificial immune systems. The suggested technique achieved an accuracy of 97.67% with binary classification.

Table 1. Summary of the previous works

|

Ref# |

Authors (Year) |

Algorithm |

Feature selection method |

Dataset |

Results (Accuracy) |

|

Ref [16] |

Rakshit et al. (2019) |

ARI-LSTM |

Not Applied |

Self-created Ransomware dataset |

93% |

|

Ref [17] |

Odat E. et al. (2023) |

Random Forest |

Proposed Feature selection method based on FP-growth algorithm |

Malgenome dataset |

98% |

|

Drebin dataset |

93% |

||||

|

Ref [18] |

Zhang S. et al. (2019) |

DNN model |

Not Applied |

Self-created malware dataset |

97.79% |

|

Ref [19] |

Danial et al. (2018) |

linear regression, JRIP, and J48 decision tree |

Not Applied |

Self-created spyware dataset |

92.32% |

|

Ref [20] |

Almash hadani et al. (2019) |

Random Trees |

Not Applied |

Self-created Locky ransomware dataset |

97.92% |

|

Ref [21] |

Kento et al. (2018) |

Proposed method |

Not Applied |

URSNIF banking spyware |

Not provided |

|

Ref [22] |

Akhtar et al. (2023) |

KNN |

Proposed feature ranking |

From Kaggle library |

98.69% |

|

Ref [23] |

Gumaa M. A. (2021) |

KNN |

Not Applied |

Self-created malware dataset |

96.50% |

|

Ref [24] |

S. Poornima et al. (2024) |

KNN |

Proposed Feature selection |

CICAndMal2017 datasets |

97.78% |

|

Ref [25] |

Radwan, A.M (2019) |

KNN |

Proposed Feature selection |

Self-created malware dataset |

98.70% |

|

Ref [26] |

Akhtar M.S. et al. (2022) |

KNN |

Proposed feature ranking |

Not provided |

95.02% |

|

Ref [27] |

Alkahtani H. et al. (2022) |

KNN |

Proposed Feature selection based on CNN-LSTM |

CICAndMal2017 |

90% |

|

Ref [28] |

Luhr J. et al. (2022) |

MLP |

PCA |

CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset |

99.93% in binary classification |

|

75.91% multiclass classification |

|||||

|

99.95% in binary classification |

|||||

|

79.11% multiclass classification |

|||||

|

Ref [29] |

Carrier et al. (2022) |

ensemble learning |

Not-Applied |

CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset |

99% binary classification |

|

Ref [30] |

Mezina et al. (2022) |

DCNN |

Not-Applied |

CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset |

99% in binary classification |

|

83% multiclass classification |

|||||

|

Ref [31] |

Jerbi et al. (2023) |

Suggested technique based on Memetic Algorithm and an Artificial Immune system |

Proposed based on adapted Memetic Algorithm |

CICMalMem-2022 dataset |

97.67% binary classification |

The first category of the preceding works [16 – 21] presents several methods to handle the issue of malware detection. However, none of these methods have used feature selection methods or the KNN ML classifier to distinguish the malware from the benign instances. Moreover, though some of these methods have achieved high accuracy in malware detection [18- 20], The findings present an opportunity to suggest a novel methodology for improving malware exposure. Finally, the suggested methods have been evaluated utilizing different datasets, but not the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset, which contains samples for abusing malware that is concealed in memory and is utilized to abuse the weaknesses in MS Windows. The main goal of discussing the studies in the first category is to show the achievement of different alternative methods in malware detection. The second category of the preceding works [22-27] presents a set of methods to handle the malware detection issue using the KNN classifier. While these methods employ different feature selection techniques, none incorporate metaheuristic optimization techniques. Moreover, though some of these methods have achieved high accuracy in malware detection [22-25], The findings present an opportunity to suggest a novel methodology for improving malware exposure. Finally, the suggested methods have been evaluated utilizing different datasets, but not the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset. The main goal of discussing the works in the second category is to show the achievement of the KNN classifier (the classifier used in this work) in malware detection. The third category of the previous studies [28-31] presents the methods to handle the issue of malware detection and has been evaluated on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset. Similar to the first category [16 – 21] and second category [22-27], the methods in the third category [28-31] use various techniques for feature selection but not any of the metaheuristic optimization techniques. In addition, none of them used the KNN classifier to distinguish the malware from benign instances. While existing methods have shown high accuracy in detecting malware, the results open the door for introducing a new approach to enhance detection capabilities further. Table 1 summarizes the preceding works. The works in the third category are the main concentration of this work, as they handle the same problem this work aims to handle.

This work focuses on malware that is concealed within the memory to abuse the weaknesses of MS Windows. To our knowledge, only the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset contains such malware. Therefore, this work will be using the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset. In addition, this work will use metaheuristic optimization techniques, particularly the FA algorithm, for feature selection. Finally, a customized version of the KNN classifier that tailors the hyperparameters specifically for the proposed AMD system.

Table 2. CIC-MalMem-2022 features

|

# |

Feature Name |

# |

Feature Name |

# |

Feature Name |

|

1 |

pslist.nproc |

20 |

handles.nmutant |

39 |

psxview.not in eprocess pool false avg |

|

2 |

pslist.nppid |

21 |

ldrmodules.not in load |

40 |

psxview.not in ethread pool false avg |

|

3 |

pslist.avg threads |

22 |

ldrmodules.not in init |

41 |

psxview.not in pspcid list false avg |

|

4 |

pslist.nprocs64bit |

23 |

ldrmodules.not in mem |

42 |

psxview.not in csrss handles false avg |

|

5 |

pslist.avg handlers |

24 |

ldrmodules.not in load avg |

43 |

psxview.not in session false avg |

|

6 |

dlllist.ndlls |

25 |

ldrmodules.not in init avg |

44 |

psxview.not in deskthrd false avg |

|

7 |

dlllist.avg dlls per proc |

26 |

ldrmodules.not in mem avg |

45 |

modules.nmodules |

|

8 |

handles.nhandles |

27 |

malfind.ninjections |

46 |

svcscan.nservices |

|

9 |

handles.avg handles per proc |

28 |

malfind.commitCharge |

47 |

svcscan.kernel drivers |

|

10 |

handles.nport |

29 |

malfind.protection |

48 |

svcscan.fs drivers |

|

11 |

handles.nfile |

30 |

malfind.uniqueInjections |

49 |

svcscan.process services |

|

12 |

handles.nevent |

31 |

psxview.not in pslist |

50 |

svcscan.shared process services |

|

13 |

handles.ndesktop |

32 |

psxview.not in eprocess pool |

51 |

svcscan.interactive process services |

|

14 |

handles.nkey |

33 |

psxview.not in ethread pool |

52 |

svcscan.nactive |

|

15 |

handles.nthread |

34 |

psxview.not in pspcid list |

53 |

callbacks.ncallbacks |

|

16 |

handles.ndirectory |

35 |

psxview.not in csrss handles |

54 |

callbacks.nanonymous |

|

17 |

handles.nsemaphore |

36 |

psxview.not in session |

55 |

callbacks.ngeneric |

|

18 |

handles.ntimer |

37 |

psxview.not in deskthrd |

||

|

19 |

handles.nsection |

38 |

psxview.not in pslist f a lse a v g |

Table 3. Types of CIC-MalMem-2022 malware

|

Types Malware |

Subtypes Malware |

# of Samples |

|

Ransomware |

Shade |

2128 |

|

Ako |

2000 |

|

|

MAZE |

1958 |

|

|

Conti |

1988 |

|

|

Pysa |

1717 |

|

|

Sum |

9791 |

|

|

Spyware |

Transponder |

2410 |

|

Gator |

2200 |

|

|

Coolwebsearch |

2000 |

|

|

TIBS |

1410 |

|

|

180Solutions |

2000 |

|

|

Sum |

10020 |

|

|

Trojan Horse |

scar |

2000 |

|

Emotet |

1967 |

|

|

Zeus |

1950 |

|

|

Refroso |

2000 |

|

|

Reconyc |

1570 |

|

|

Sum |

9487 |

|

|

Total |

29,298 |

|

3. CIC-MalMem-2022 Dataset

The Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity released the academic dataset CIC-Malmem2022 to support research on classifying malware, specifically focusing on obfuscated malware. The dataset is created to evaluate obfuscated malware detection techniques using memory. The CIC-Malmem2022 dataset was designed to closely mimic real-world scenarios by including popular malware found in actual environments. The dataset is created by a controlled procedure of extracting features from memory dumps. The CIC-Malmem2022 dataset has 55 features and 58,596 records, with 29,298 classified as benign and 29,298 as malicious. Table 2 displays the features of the CIC-Malmem2022 dataset. Table 3 displays how the dataset records are distributed across various forms of malware. Based on the numbers shown in Table 3, the CIC-Malmem2022 dataset is considered to be balanced in binary classification (contains an equal number of benign and malicious samples). However, it is considered slightly imbalanced in the multiclass classification context (malicious samples are categorized into various malware families, including Emotet, Conti, Zeus, etc.); the sample counts across different malware families vary. The dataset does not include features that represent the temporal aspect of malware behavior, often called "aging features." These features usually describe how malware changes over time, such as shifts in behavior or code structure. Instead, the dataset mainly contains static features extracted from memory dumps without any time-based sequence or metadata [29-31].

4. Proposed AMD System

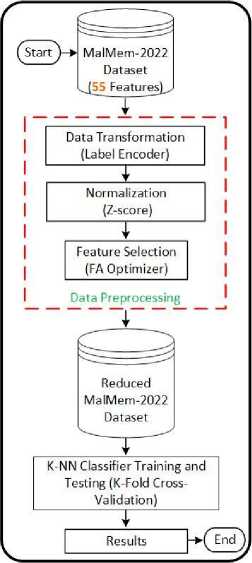

This section discusses the proposed AMD system that will be used to detect the malware. Several steps are performed to build the AMD system for malware detection. First, the categorical data within the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset is transformed into numbers. Then, the data with the large scale will be normalized into a compatible scale. After that, the key features for detecting the malware will be selected using the FA optimization algorithm. Finally, the KNN classifier will be trained and evaluated using different hyperparameter values to achieve the best performance detecting malware. Fig. 1 overview the steps performed to build the AMD system. These steps are detailed in the following subsections.

Fig.1. Steps to build the AMD system

-

4.1. CIC-MalMem-2022 Dataset Preprocessing

The label column in the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset contains non-numeric data. The label encoding technique has converted the label column values into numbers [32,33]. This article will evaluate the suggested AMP system using scenarios of binary classification and four and 16 classes of multiclass classification. Accordingly, the label encoding mechanism will change the content of the label column into two, four, or 16 unique values based on the scenario. In the case of binary classification, the label column will have the values 0 and 1. In the case of 4 classes, the label column will have the values 0, 1, 2, and 3. In the case of 16 classes, the label column will have the values 0, 1, 2, and 15.

-

4.2. Features Selection using FA Algorithm

On the other hand, the values within features of the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset are distributed over a large scale, negatively impacting the performance of the suggested AMP system. Therefore, the Z-score normalization mechanism has been used to decrease the scale of the values so that it has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 [32,33]. At this point, the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset is prepared for feature selection algorithms to be applied. Tables 4 and 5 show a sample of the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset before and after preprocessing, respectively.

Table 4. Sample of the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset before preprocessing

|

Random Sample of features |

Label |

|

52.05,12245,12,306.125,2082,13.55 |

Benign |

|

51.34146341,12496,12,304.7804878,2105,13.41463415 |

MAZE |

|

46.92682927,10997,16,268.2195122,1924,11.6097561 |

Coolwebsearch |

|

47.28125,9077,11,283.59375,1513,12.53125 |

Refroso |

Table 5. Sample of the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset after preprocessing

|

Random Sample of features |

Label |

|

–0.5404, 2.2055, -0.5494, -0.4832, -0.0833, -0.5491 |

0 |

|

-0.5396, 2.2060, -0.5483, -0.4837, -0.0865, -0.5480 |

1 |

|

-0.5426, 2.2036, -0.5504, -0.4871, -0.0718, -0.5515 |

10 |

|

-0.5407, 2.2070, -0.5517, -0.4687, -0.0947, -0.5512 |

11 |

One popular optimization approach for feature selection is the FA algorithm. FA is an optimization technique inspired by nature, based on how fireflies flash. The FA optimization technique is useful for feature selection in malware detection for several reasons. First, the FA aims to search for solutions globally. This suggests that it can explore a lot of feature subsets and help find a solution that is either nearly ideal or globally optimal. Second, the parallel exploration of the FA algorithm allows it to converge toward promising regions of the solution space quickly. Third, the algorithm automatically prioritizes more promising portions of the solution space. This can lead to a more efficient search by reducing the computing cost of evaluating feature subsets. Fourth, the FA algorithm is well known for its ability to adapt to changing environments where different actions may be best [12,13,34,35]. The core principle of FA is that fireflies communicate and entice one another through bioluminescent flashing. Fireflies that emit more light are seen as more attractive and are more likely to draw in other fireflies. The algorithm mimics this behaviour in order to identify solutions that are either optimal or very close to optimal. Fig. 2 shows the flashing behaviour of fireflies.

Fig.2. Flashing behaviour of fireflie s [12]

The FA algorithm helps find the most useful features for detecting malware [14,15,27,28]. Fig. 3 shows the basic steps the algorithm follows. The process begins by randomly initializing the fireflies’ positions in the search space (lines 1–2). Next, the algorithm calculates how attractive each firefly is based on the objective function (lines 3–4). It then determines the brightest fireflies and updates their positions accordingly (lines 5–12). If a firefly detects another one that is brighter, it moves toward it (lines 13–15) and then updates its position (line 16). The brightest firefly is tracked, and its position is updated to reflect any improvements (lines 17–18). The algorithm then recalculates the

4.3. KNN Classification Algorithm

5. Implementation, Results, and Discussion

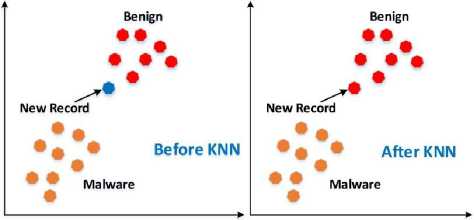

The KNN classifier is a non-parametric technique employed for both regression and classification. KNN boasts several advantages that contribute to its widespread use in classification tasks across various domains, including cybersecurity. Notably, KNN is robust, easy to interpret, and requires minimal computation time. Functioning as a lazy learning classifier, KNN does not actively learn from the training data but stores all samples within it. These stored values become essential during the training phase. KNN exemplifies instance-based learning, wherein the training set is retained, enabling the classification of new data by comparing it to the most similar records in the training set. The KNN classifier operates through the following steps: i) Define a positive integer value k along with the new sample, ii) Select the k values in the dataset closest to the new testing sample, iii) Determine the most similar classification among these entries, iv) Assign this classification to the new sample using the defined value of k, and v) If satisfactory results are not achieved, adjust the value of k until the correct results are obtained [36-38]. Fig. 5 demonstrates the KNN classifier.

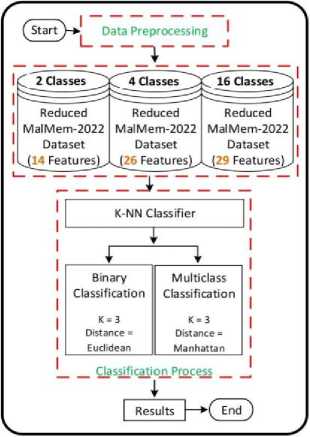

Fig.5. KNN algorithm

The ML KNN classifier involves several hyperparameters that must be carefully set to optimize performance for a specific application. Among these, the key KNN hyperparameters are K and the distance metric. Assigning the appropriate values to these hyperparameters is crucial for enhancing the performance of the proposed AMD system [3638]. This paper aims to propose a customized KNN (C-KNN) that tailors the K and distance metric hyperparameters specifically for the proposed AMD system. It is essential to note that there is no universally ideal value for K and the distance metric. Determining the best values for K and the distance metric requires systematic investigation and analysis, contingent on the specific dataset and circumstances. To achieve this, numerous tests have been conducted on C-KNN using different K values and distance metrics, particularly on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset for the suggested AMD system. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using Grid Search, a method that exhaustively tests a range of possible combinations of K values and distance metrics. This process systematically evaluates each configuration, measuring performance through cross-validation, and identifies the set of hyperparameters that produces the highest accuracy, ensuring the most effective model configuration. Based on the investigations on the MalMem-2022 dataset and insights from preceding work, the value of K is three in binary classification and four and 16 classes in multiclass classification. Regarding the distance metric, in binary classification, the Euclidean distance metric has consistently achieved excellent outcomes. On the other hand, in multiclass classification, the Manhattan distance metric is favored.

The suggested AMD system is now prepared to identify and detect malware. Fig. 6 illustrates the AMD system. In the subsequent section, the AMD system's performance will be assessed.

The suggested AMD system is assessed on a PC with the following specs: Intel Corei7-13700K processor, 16GB RAM, 1TB SSD, Nvidia Geforce RTX 4090 24 GB, and Ubuntu 22.04. The system was developed using Python, which is a large number of tools for developing and implementing ML systems [30]. The K-fold cross-validation technique is employed to assess the performance of the AMD system. The CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset is partitioned into five subgroups using K-fold cross-validation, ensuring that each subset has a similar size. The system is thereafter trained and assessed five times, with each iteration utilizing a distinct fold as the validation set and the remaining k-1 folds as the training set. K-fold cross-validation offers a reliable and impartial evaluation of a system's performance by tackling concerns relating to data partitioning, model variability, and the potential influence of a particular training/test split [39].

The achievement of the AMD system is assessed using binary and multiclass. The suggested AMD system is assessed utilizing the confusion matrix (Fig. 7): True positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN). Five metrics are built upon the confusion matrix to evaluate the achievement of the AMD system in malware detection. These metrics are Accuracy (ACC), Recall (Rec), Precision (Pre), Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and F1-score. Acc is inversely proportional to the difference between the true and predicted classes. The Acc is calculated using Equation 1. Rec is the ratio of actual positives that are correctly identified. The Rec is computed using Equation 2. Pre measures the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified. The Pre is calculated using Equation 3. MCC is a measure of the quality of classification with two classes. The MCC is calculated using Equation 4.

F1-score is the harmonic mean of Pre and Rec, balancing both metrics to provide a single measure. The F1-Score is calculated using Equation 5 [40-42].

Fig.6. AMD system

Predicted Predicted

Negative Positive

Actual Negative

Actual

Positive

|

TN |

FP |

|

FN |

TP |

Fig.7. Confusion matrix

Besides the previous five metrics, the False Positive Rate (FPR), True Negative Rate (TNR), and False Negative Rate (FNR) will be used in the evaluation of the AMD system. These metrics offer finer-grained insights into the types of classification errors, which are especially critical where false positives and false negatives have very different implications. FPR (Type I error) is vital for minimizing disruption from falsely flagged benign samples. FNR (Type II error) is crucial in malware detection, as false negatives allow threats to pass undetected. TNR helps quantify the model's ability to identify benign samples correctly. Equations 6, 7, and 8 can be used to calculate the FPR, FNR, and TNR of the AMD system.

Accuracy = (TP + TN )/(TP + TN + FP + FN )(1)

Precision = TP/(TP + FP )(2)

Recall = TP/(TP + FN )(3)

MCC = (TPTN - FPFN )/ √((TP + FP) × (TP + FN) × (TN + FP) × (TN + FN))(4)

F 1 - score = 2(PrecisionRecall)/(Precision + Recall)(5)

FPR = FP/(TN + FP )(6)

FNR = FN/(TP + FN )(7)

TNR = TN/(TN + FP )(8)

-

5.1. Performance Assessment of the AMD System

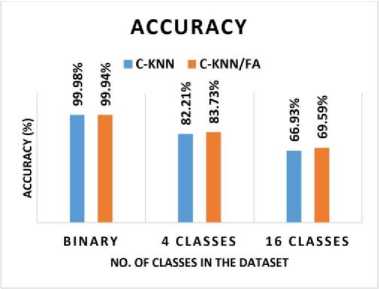

Fig. 8 shows the Acc of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes). C-KNN achieved a binary classification Acc of 99.98%, whereas C-KNN/FA achieved an Acc of 99.94%. In the 4 classes classification, C-KNN has accomplished an Acc of 82.21%, and C-KNN/FA has accomplished an Acc of 83.73%. In 16 class classifications, C-KNN has accomplished an Acc of 66.93%, and C-KNN/FA has an Acc of 69.59%. Hence, both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have accomplished great Acc results in malware detection. However, C-KNN accomplished a slightly higher Acc of 0.04% compared to C-KNN/FA in binary classification, C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher Acc of 1.52% compared to C-KNN in 4 classes classification, and C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher Acc of 2.66% compared to C-KNN in 16 classes classification.

Fig.8. Acc of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes)

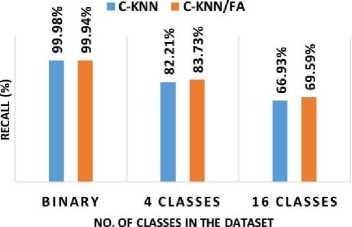

Fig. 9 shows the Rec of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes). C-KNN achieved a binary classification Rec of 99.98%, whereas C-KNN/FA achieved a Rec of 99.94%. In the 4 classes classification, C-KNN has accomplished a Rec of 82.21%, and C-KNN/FA has accomplished a Rec of 83.73%. In 16 class classifications, C-KNN has accomplished a Rec of 66.93%, and C-KNN/FA has a Rec of 69.59%. Hence, both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have accomplished great Rec results in malware detection. However, C-KNN accomplished a slightly higher Rec of 0.04% compared to C-KNN/FA in binary classification, C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher Rec of 1.52% compared to C-KNN in 4 classes classification, and C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher Rec of 2.66% compared to C-KNN in 16 classes classification.

RECALL

Fig.9. Rec of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes)

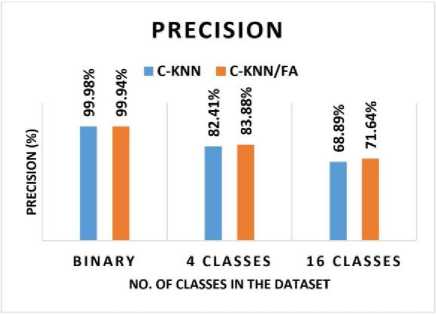

Fig. 10 shows the Pre of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes C-KNN achieved a binary classification Pre of 99.98%, whereas C-KNN/FA achieved a Pre of 99.94%. In the 4 classes classification, C-KNN has accomplished a Pre of 82.41%, and C-KNN/FA has accomplished a Pre of 83.88%. In 16 class classifications, C-KNN has accomplished a Pre of 68.89%, and C-KNN/FA has a Pre of 71.64%. Hence, both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have accomplished great Pre results in malware detection. However, C-KNN accomplished a slightly higher Pre of 0.04% compared to C-KNN/FA in binary classification, C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher Pre of 1.47% compared to C-KNN in 4 classes classification, and C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher Pre of 2.75% compared to C-KNN in 16 classes classification.

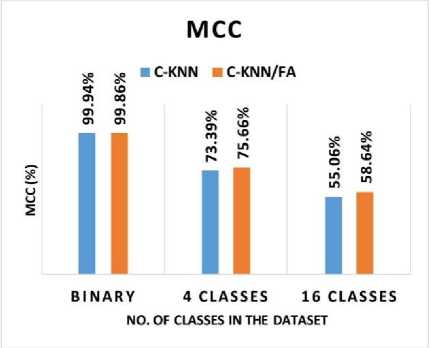

Fig. 11 shows the MCC of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes). C-KNN achieved a binary classification MCC of 99.94%, whereas C-KNN/FA achieved an MCC of 99. 86%. In the 4 classes classification, C-KNN has accomplished an MCC of 73.39% and C-KNN/FA has accomplished an MCC of 75.66%. In 16 class classifications, C-KNN has accomplished an MCC of 55.06%, and C-KNN/FA has an MCC of 58.64%. Hence, both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have accomplished great MCC results in malware detection. However, C-KNN accomplished a slightly higher MCC of 0.08% compared to C-KNN/FA in binary classification, C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher MCC of 2.27% compared to C-KNN in 4 classes classification, and C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher MCC of 3.58% compared to C-KNN in 16 classes classification.

Fig.10. Pre of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes)

Fig.11. MCC of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes)

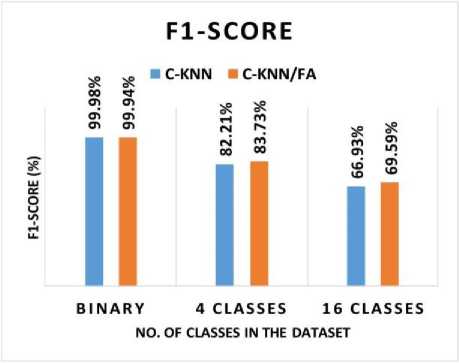

Fig. 12 shows the F1-score of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes). C-KNN achieved a binary classification F1-score of 99.98%, whereas C-KNN/FA achieved an F1-score of 99.94%. In the 4 classes classification, C-KNN has accomplished an F1-score of 82.21%, and C-KNN/FA has an F1-score of 83.73%. In 16 class classifications, C-KNN has accomplished an F1-score of 66.93%, and C-KNN/FA has an F1-score of 69.59%. Hence, both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have accomplished great F1-score results in malware detection. However, C-KNN accomplished a slightly higher F1-score of 0.04% compared to C-KNN/FA in binary classification, C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher F1-score of 1.52% compared to C-KNN in 4 classes classification, and C-KNN/FA accomplished a slightly higher F1-score of 2.66% compared to C-KNN in 16 classes classification.

Fig.12. F1-score of the AMD system with binary and multiclass (4 classes and 16 classes)

-

5.2. TNR, FPR, and FNR

-

5.3. Performance Assessment of the AMD System Against Other Methods

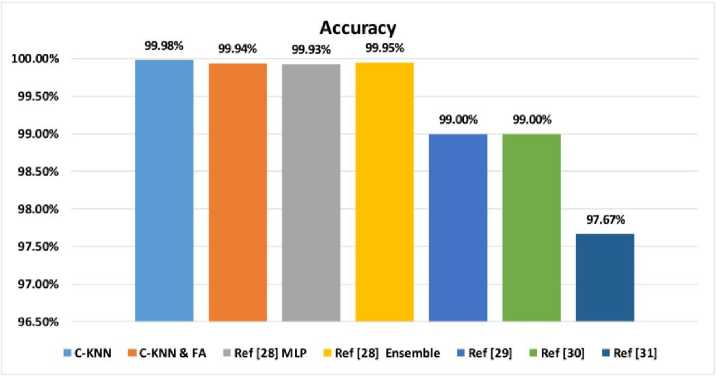

Fig. 13 displays the accuracy of the proposed AMD system compared to other methods on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset using binary classification. It is evident that the C-KNN method outperforms all other applied methods on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset in binary classification. The closest technique ([28]-Ensemble) attained an accuracy of 99.95%, while the proposed C-KNN method achieved a slightly higher accuracy of 99.98%. Consequently, the proposed C-KNN method outperforms the closest method by 0.03% in terms of accuracy in binary classification.

86.00»

Table 7. compares the performance of the C-KNN classifier and C-KNN enhanced with the FOA across binary, 4-class, and 16-class multiclass classifications in terms of TNR, FPR, and FNR. In binary classification, C-KNN alone outperforms C-KNN/FOA across all three metrics, with C-KNN/FOA showing slight degradations in TNR, FPR, and FNR by 0.04. However, in multiclass classification, integrating FOA consistently improves performance. For the 4-class classification, C-KNN/FOA shows improvements in TNR (by 0.4%), FPR (by 0.39%), and FNR (by 1.52%). In the more complex 16-class classification, C-KNN/FOA achieves an improvement of 0.19% in TNR, 0.18% in FPR, and 2.65% in FNR. These results suggest that while FOA may not benefit simpler binary classification tasks, it significantly enhances the robustness of C-KNN in handling more complex, high-class-count malware detection scenarios.

Table 7. TNR, FPR, and FNR results

|

Classes |

TNR (%) |

FPR (%) |

FNR (%) |

|||

|

C-KNN |

C-KNN/FA |

C-KNN |

C-KNN/FA |

C-KNN |

C-KNN/FA |

|

|

Binary |

99.96 |

99.92 |

0.04 |

0.08 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

|

4 Classes |

94.72 |

95.12 |

4.27 |

3.88 |

17.78 |

16.26 |

|

16 Classes |

97.85 |

98.04 |

2.14 |

1.96 |

33.06 |

30.41 |

Fig.13. Acc of the AMD system versus other methods on CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset (binary classification)

Accuracy

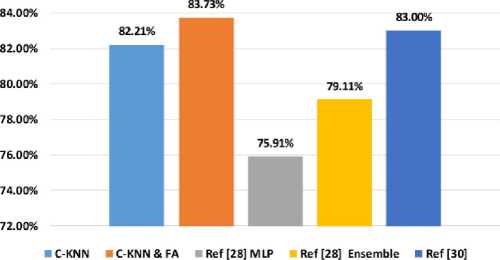

Fig.14. Acc of the AMD system versus other methods on CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset (4 classes)

Fig. 14 displays the accuracy of the proposed AMD system compared to other methods on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset using multiclass classification. Clearly, the C-KNN/FA method outperforms all other applied methods on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset in multiclass classification. The closest technique [30] attained an accuracy of 83.00%, while the proposed C-KNN/FA method achieved a slightly higher accuracy of 83.73%. Consequently, the proposed C-KNN/FA method outperforms the closest method by 0.73% in terms of accuracy in multiclass classification.

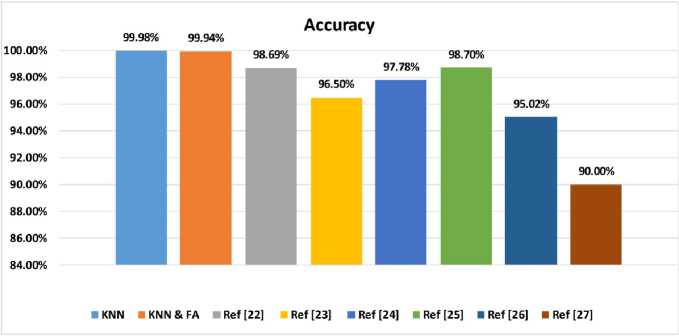

Fig. 15 illustrates the accuracy of the proposed AMD system compared to other methods across various datasets, alongside the typical KNN, focusing on binary classification. Notably, both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA outperform other methods in binary classification tasks. The nearest method [25] achieved an accuracy of 98.70%, while the proposed C-KNN and C-KNN/FA methods achieved even higher accuracies at 99.98% and 99.94%, respectively. Consequently, the proposed C-KNN and C-KNN/FA methods outperform the closest method by 1.28% and 1.24%, respectively, in terms of accuracy in binary classification.

Fig.15. Acc of the AMD system against other methods using KNN classifier (binary classification)

Fig. 16 depicts the accuracy of the proposed AMD system in contrast to other methods across various datasets, utilizing different classification methods for binary classification. In the Fig. 16, [17.M] pertains to reference 3 using the Malgenome dataset, while [17.D] corresponds to reference 3 using the Drebin dataset. As depicted in Fig. 16, both the C-KNN and C-KNN/FA outperform other methods in binary classification tasks. The closest method [17.M] attained an accuracy of 98.00%, while the proposed C-KNN and C-KNN/FA methods achieved notably higher accuracies at 99.98% and 99.94%, respectively. Consequently, the proposed C-KNN and C-KNN/FA methods outperform the nearest method by 1.98% and 1.94%, respectively, in terms of accuracy in binary classification.

Fig.16. Acc of the AMD system against other methods on various dataset (binary classification))

In summary, the C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have achieved notable results in malware detection. In binary classification, C-KNN outperforms C-KNN/FA in terms of Acc, Rec, Pre, and F1-score by 0.04% and MCC by 0.09%. However, in multiclass four classes 16 classes classification, C-KNN/FA exhibits superior performance over C-KNN. For 4 classes, C-KNN/FA surpasses C-KNN in Acc, Rec, and F1-score by 1.52%, Pre by 1.47%, and MCC by 2.27%, Similarly, in 16 classes, C-KNN/FA outperforms C-KNN in Acc and Rec by 2.66%, Pre by 2.75, MCC by 3.58, and F1-score by 2.66%. Both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA outperform alternative approaches evaluated using the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset in binary and 4 class classifications. In binary classification, C-KNN surpasses the nearest approach by 0.03% in accuracy, while in 4 classes of classification, C-KNN/FA outperforms the nearest approach by 0.73%. Furthermore, when compared to alternative approaches utilizing various classification methods with different datasets, both C-KNN and C-KNN/FA exhibit superior accuracy. In particular, they outperform the nearest approach that employs the KNN classifier by 1.28% and 1.24%, respectively. Additionally, when compared to the nearest approach using other classification methods and different datasets, C-KNN and C-KNN/FA outperform by 1.98% and 1.94%, respectively. The difference in numbers between the AMD model and the previous model is small. However, in high-risk cybersecurity situations, even tiny improvements can make a big difference, like identifying hundreds or thousands more threats correctly. The small performance gap also suggests that while ensemble methods are strong, C-KNN's main strength may be its simplicity, efficiency, and ability to handle memory-based malware behaviors. This makes it a good choice for use in places with limited computer power or where quick decisions are needed.

5. Conclusions

The primary focus of this research is to investigate the performance of the C-KNN classifier, which uses specific K and distance metric values for malware detection. This research also presents the FA algorithm as a means of selecting pertinent features, significantly enhancing malware instance identification techniques. The experiments are comparing the performance of the C-KNN and C-KNN/FA methods. The research findings suggest that selecting optimal values for K, adopting appropriate distance metrics, and utilizing FA for feature selection can significantly enhance malware classification performance. The C-KNN and C-KNN/FA have produced remarkable results in malware identification, reaching an accuracy of 99.98%. This accomplishment is quite encouraging. The obtained findings underscore the importance of fine-tuning KNN parameters and utilizing feature selection approaches to enhance accuracy, especially in malware detection. Future work will explore real-time deployment of the proposed system, assess its resilience against adversarial attacks, and optimize it for low-resource environments to support practical and scalable implementation.