Abiotic stress, Seed germination, Salt tolerance

Автор: Renu Rajan, Ramseena K.M., Sreelakshmi Rajesh

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

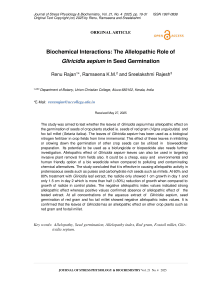

The study was aimed to test whether the leaves of Gliricidia sepium has allelopathic effect on the germination of seeds of crop plants studied ie. seeds of red gram (Vigna unguiculata) and fox tail millet (Setaria italica). The leaves of Gliricidia sepium has been used as a biological nitrogen fertilizer in crop fields from time immemorial. This effect of these leaves in inhibiting or slowing down the germination of other crop seeds can be utilized in bioweedicide preparation. Its potential to be used as a biofungicide or biopesticide also needs further investigation. Allelopathic effect of Gliricidia sepium leaves can also be used in targeting invasive plant removal from fields also. It could be a cheap, easy and environmental and human friendly option of a bio weedicide when compared to polluting and contaminating chemical alternatives. The study also concluded that it is effective in causing allelopathic activity in proteinaceous seeds such as pulses and carbohydrate rich seeds such as millets. At 60% and 80% treatment with Gliricidia leaf extract, the radicle only showed 1 cm growth in day 1 and only 1.5 cm in day 2 which is more than half (>50%) reduction of growth when compared to growth of radicle in control plates. The negative value indicates strong allelopathic effect whereas positive values confirm absence of allelopathic effect of the tested extract. At all the concentrations of the aqueous extract of Gliricidia sepium on seed germination of red gram and fox tail millet showed negative values. It is confirmed that the leaves of Gliricidia have an allelopathic effect on other crop plants such as red gram and foxtail millet.

Allelopathy, Seed germination, Allelopathy index, Red gram, Foxtail millet, Gliricidia sepium

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143185120

IDR: 143185120

Текст научной статьи Abiotic stress, Seed germination, Salt tolerance

The detrimental effects of synthetic herbicides on the environment and human health have spurred increased interest in eco-friendly alternatives for weed control, including allelopathy. Gliricidia sepium has been found to have potential to be used as a potent synthetic herbicide in tea plantations of Sri Lanka to control weeds (Ranawana et al. , 2024). Interference may occur when one plant species fails to germinate, grows more slowly, shows symptom of damage, or does not survive in the presence of another plant species. Such interference can result from competition and allelopathy. The interaction of plants through chemical signals has many possible agricultural applications (Nelson, 1996). Decline in crop yields in cropping and agroforestry system in recent years has been attributed to allelopathic effects. It has been reported that Eucalyptus spp. and Acacia spp. have phytotoxic effects on tree crops and legumes (Velu et al. , 1999). Also, Menges (1987), observed that incorporation of residues of Palmer amaranth in the soil inhibited the growth of carrot and onion. Allelopathic associated problems often result to accumulation of phytotoxin and harmful microbes in soil, which give rise to phytotoxicity and soil thickness (Sahar et al. , 2005).

A large number of weeds and tree possess allelopathic properties, which have growth inhibiting effect on crops. Thus, chemicals with allelopathic activity are present in many plants and various organs, including leaves (Inderjit, 1966) and fruits (Rice,1984) and have potential inhibitory effects on crops (Seigler 1996). Many allelopathic compounds produced by plants are released to the environment by means of volatilization, leaching, decomposition of residue and root exudation.

Weeds are one of the most challenging problems facing agricultural production all over the world. Weeds compete for light, nutrients, water, and space that reduce crop growth and yield. Additionally, weeds also attract insect pests, bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens, further reducing the crop yield. (Chauhan, 2020). There are various ways to control weeds which include physical chemical and biological means. Agriculture in developed countries mainly relies on synthetic herbicides to control weeds. The heavy reliance on herbicides resulted the development of herbicide- resistant weeds. (Heap, 2022). In addition, there are several other negative consequences related to heavy use of herbicides, such as high chemical costs, potential leaching and runoff into groundwater, or concerns with recycling irrigation water (Poudyal and Cregg, 2019). Public concerns over the impact of herbicides on human health and the environment are also increasing. Due to the evolution of herbicide- resistant weeds and public awareness with synthetic herbicides, there is a need to develop a sustainable ecofriendly tool to manage weeds. One great field for discovering such tools is the use of plant based natural compounds called allelochemicals to control weeds. These allelopathic chemicals have phytotoxic activities with the potential to be used for suppressing certain weeds as natural herbicides.

Allelopathy refers to the direct or indirect effect of plants upon neighboring plants or their associated microflora or microfauna by the production of allelochemicals that interfere with the growth of the plant (IAS, 2018). The allelochemicals released from the plants act as a defense system against microbial attack herbivore predation, or competition from other plants (Kong et al., 2019). The study of allelopathy is a subdiscipline of chemical ecology that focuses on the effects of chemicals produced by plants or microorganisms on the growth and development of other plants in natural or agricultural systems (Einhellig, 1995). The effect can be either positive or negative on the growth of the surrounding plants. The word allelopathy is derived from two separate Greek words, allelon meaning of each other or mutual and pathos meaning to suffer or feeling. Even though the term ‘allelopathie’ was first used by Austrian scientist Hans Molisch in 1937 (Willis, 2007), the chemical interaction between plants has been known for thousands of years. In 300 B.C, the Greek botanist Theophrastus mentioned the negative effects of chickpea on other plants and later Pliny, a Roman scholar (1 A.D.) noted the inhibitory effect of the walnut tree over nearby crops. The allelochemicals are released from plant a part by leaching from leaves or litter on the ground, root exudation, volatilization from leaves, residue decomposition, and other processes in the natural and agricultural field (Anaya, 1999). Upon release, the allelochemicals can suppress the germination, growth, and establishment of the surrounding plants or modify the soil properties in the rhizosphere by influencing the microbial community (Zhou et al., 2013). Since allelopathic substances play an important role in regulating the plant communities, they can also be used as natural biodegradable herbicides (Duke S. et al., 2000).

Research on allelopathy was traditionally focused on assessing the phytotoxic activities of plant residues or crude extracts. Recent allelopathic studies made great improvements with rapid progress in separation and structural elucidation techniques, active compounds can be detected, isolated, and characterized. Allelochemicals are produced by plants as secondary metabolites or by microbes through decomposition. Allelochemicals are classified into 14 categories based on their chemical similarities (Rice, 1984). The 14 categories are water soluble organic acids, straight- chain alcohols, aliphatic aldehydes and ketones; simple unsaturated lactones; long-chain fatty acids and polyacetylenes; benzoquinone, anthraquinone and complex quinones; simple phenols, benzoic acid and its derivatives; cinnamic acid and its derivatives; coumarin; flavonoids; tannins; terpenoids and steroids; amino acids and peptides; alkaloids and cyanohydrins; sulfide and glucosinolates; and purines and nucleosides (Cheng and Cheng, 2015)

Plant growth regulators, such as salicylic acid, gibberellic acid, and ethylene are also considered to be allelochemicals. Allelochemicals vary in mode of action, uptake, and effectiveness. The mode of action for many of the identified allelochemicals is still unclear. Many allelochemicals have mechanisms that are not used by any of the synthetic herbicides, giving researchers leads to new mode of action (Duke et al., 2002). While the efficacy and specificity of many allelochemicals are unknown or limited they are an appropriate alternative for synthetic herbicides. (Bhadoria, 2010). In this scenario the current research project has been proposed with the following objectives: Identification of allelopathic effect of Gliricidia sepium on other crop plants, study the effect of selected plant on the germination and growth of red gram and foxtail millet, identify the potent concentration of Gliricidia sepium to cause allelopathy on crop seeds and to find out the Allelopathic Index of Gliricidia sepium on seeds of Vigna unguiculata and Setaria italica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

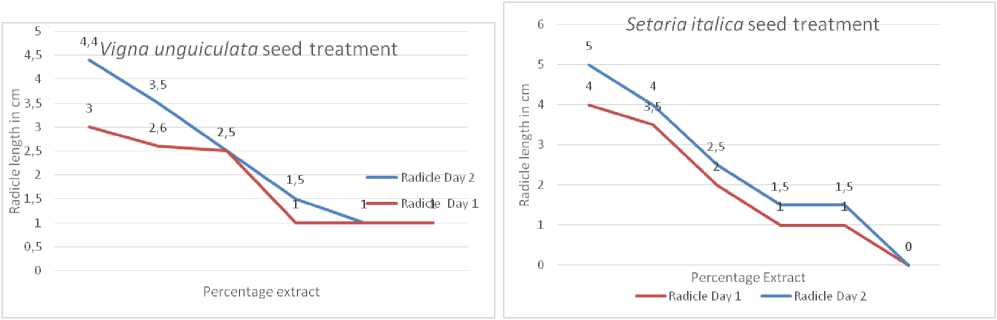

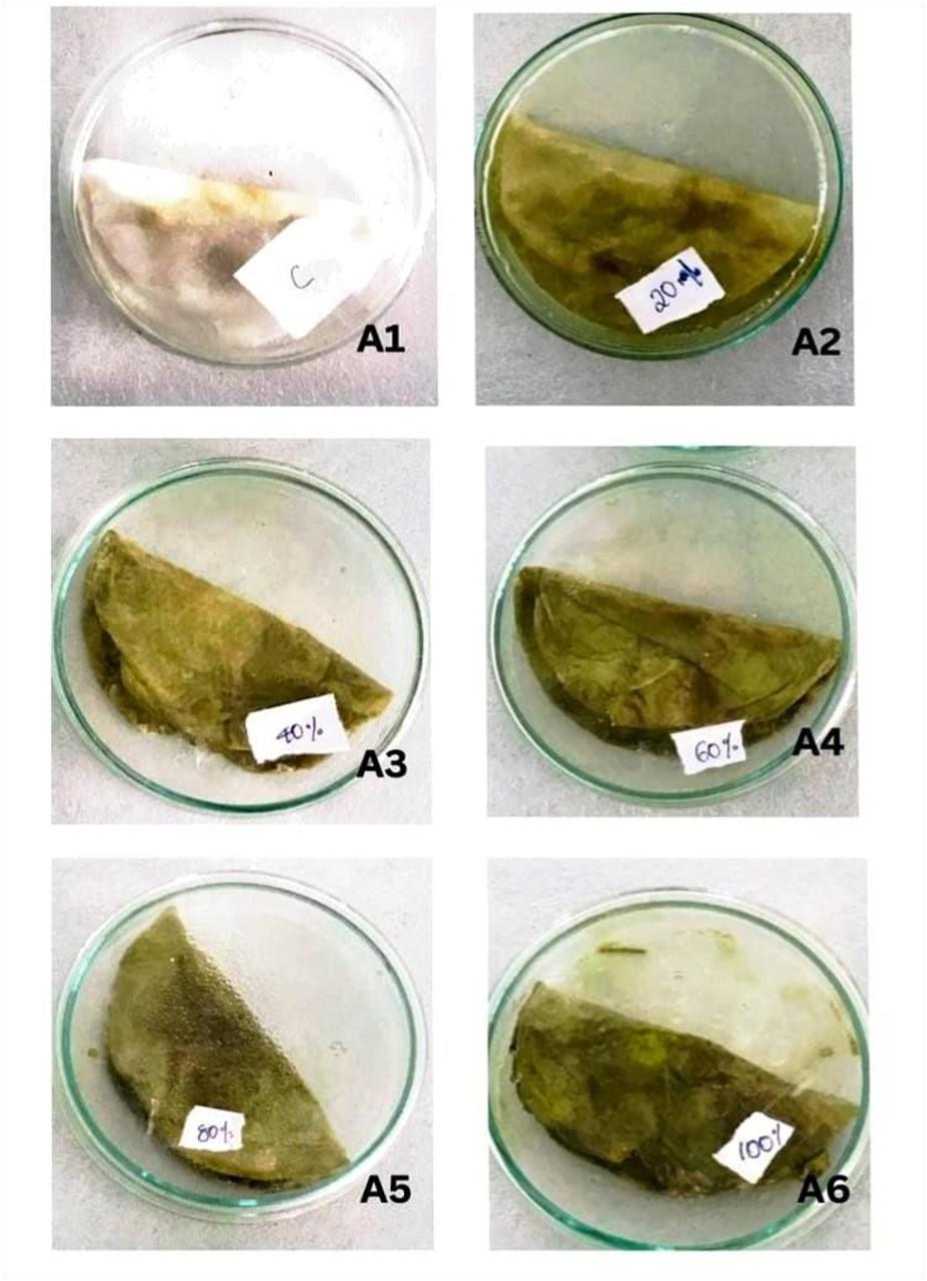

Grains of Fox tail millet- Setaria italica Fig 1(a) and seeds of Red Gram- Vigna unguiculata Fig 1(b)were obtained from market samples around Aluva. The grains were surface sterilized with 1% Sodium hypochloride for 20 mins, then rinsed with distilled water several times. Fresh samples of leaves of Gliricidia sepium Fig 1(c) were collected at random at the vegetative stage in 2025 March- April season from Aluva locality. The leaves were sun-dried and then ground using mixer grinder to pass through 2mm mesh sieve. 20% ,40%, 60%, 80% and 100% aqueous extracts of leaf samples were prepared in sterile conditions. The mixture was shaken intermittently and left for 24 hours. Thereafter, the suspension was filtered using No.1 Whatman filter paper. Three replicates per treatment of 10 seeds/grains per replicate were incubated on tissue paper in petri- dishes using the respective leachate concentration and laid in completely randomized design under laboratory condition. The tissue paper was constantly moistened twice daily using the respective leachate concentrations and distilled water as control. The petri-dishes were kept at room temperature under 12 hours of natural light each day and monitored daily. Seeds were considered germinated upon radicle emergence. The first germination was observed after a day. Readings were taken for 48 hrs.

Length of radicle and percentage germination analysis were conducted for 2 days subsequently to compare the allelopathic effect of various concentrations (0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80% and 100%) of aqueous extracts of Gliricidia sepium leaves on seeds of Setaria italica and Vigna unguiculata seeds. Radicle lengths were measured manually in cm. Germination percentage was calculated by the formula,

Germination %= (No: of seeds germinated / Total No: of seeds taken) x 100.

Allelopathic Index or Response Index (RI %) of Gliricidia sepium was calculated by the formula,

Allelopathic Index= (Total length of radicle x Length of radicle under chemical)/ (Total length of radicle x Length of radicle under control) x100

RESULTS

Allelopathic Index of different concentrations of aqueous extract of Gliricidia sepium on seeds of red gram (Table 3) and that on seeds of foxtail millet (Table 4) are tabulated above. The negative value indicates strong allelopathic effect whereas positive values confirm absence of allelopathic effect of the tested extract. As all the concentrations of the aqueous extract of Gliricidia sepium on seed germination of red gram and fox tail millet showed negative values. It is confirmed that the leaves of Gliricidia have an allelopathic effect on other crop plants such as red gram and foxtailmillet.

Table 1: Observations of experiments on Vigna unguiculata seeds

|

Conc. Of Gliricidia leaf extract on Vigna seeds |

Germination Percentage |

Mean Radicle Length |

||

|

Day 1 |

Day 2 |

Day 1 |

Day 2 |

|

|

Control (0%) |

85% |

90% |

3.0±0.023 |

4.4±0.020 |

|

20% |

75% |

90% |

2.6±0.012 |

3.5±0.011 |

|

40% |

75% |

90% |

2.5±0.011 |

2.5±0.022 |

|

60% |

50% |

65% |

1.0±0.020 |

1.5±0.016 |

|

80% |

45% |

55% |

1.0±0.011 |

1.0±0.013 |

|

100% |

40% |

50% |

1.0±0.010 |

1.0±0.022 |

Table 2: Observations of experiments on Setaria italica seeds

|

Conc. Of Gliricidium leaf extract on Setaria seeds |

Germination Percentage |

Mean Radicle Length |

||

|

Day 1 |

Day 2 |

Day 1 |

Day 2 |

|

|

Control (0%) |

80% |

85% |

4.0±0.019 |

5.0±0.015 |

|

20% |

80% |

80% |

3.5±0.015 |

4.0±0.011 |

|

40% |

75% |

80% |

2.0±0.019 |

2.5±0.013 |

|

60% |

45% |

50% |

1.0±0.017 |

1.5±0.020 |

|

80% |

15% |

20% |

1.0±0.018 |

1.5±0.017 |

|

100% |

0% |

0% |

0.0±0.016 |

0.0±0.018 |

Table 3: Allelopathic Index of Gliricidia sepium on Vigna unguiculata seed germination

|

SI NO |

EXTRACT CONCENTRATION |

ALLELOPATHIC INDEX ON RED GRAM |

|

|

DAY 1 |

DAY2 |

||

|

1 |

Control (0%) |

-67.3 |

-74.2 |

|

2 |

20% |

-75 |

-79.5 |

|

3 |

40% |

-70 |

-64 |

|

4 |

60% |

-95 |

-56.6 |

|

5 |

80% |

-55 |

-45 |

|

6 |

100% |

-50 |

-50 |

Table 4: Allelopathic Index of Gliricidia sepium on Setaria italica seed germination

|

SI NO |

EXTRACT CONCENTRATION |

ALLELOPATHY INDEX ON FOXTAIL MILLET |

|

|

DAY 1 |

DAY 2 |

||

|

1 |

Control (0%) |

-80 |

-83 |

|

2 |

20% |

-77.1 |

-80 |

|

3 |

40% |

-62.5 |

-68 |

|

4 |

60% |

-55 |

-66.6 |

|

5 |

80% |

-85 |

-86.6 |

|

6 |

100% |

0 |

0 |

Figure 1: (a): Setaria italica seeds (b): Vigna unguiculata seeds (c): Gliricidia sepium leaves

A

B

Figure 2: (a): Allelopathic effect of Gliricidia sepium leaf extract on Vigna unguiculata seeds (b): Allelopathic effect of Gliricidia sepium leaf extract on Setaria italica seeds

Figure 3: (a): Effect of Gliricidia sepium extract on Vigna unguiculata seeds Day 1, A1- Control, A2-20%, A3-40%, A4-60%, A5-80% and A6-100%

Figure 3: (b): Effect of Gliricidia sepium extract on Vigna unguiculata seeds Day 2, B1- Control, B2-20%, B3-40%, B4-60%, B5-80% and B6-100%

Figure 3: (c): Effect of Gliricidia sepium extract on Setaria italica seeds Day 1, C1- Control, C2-20%, C3-40%, C4- 60%, C5-80% and C6-100%

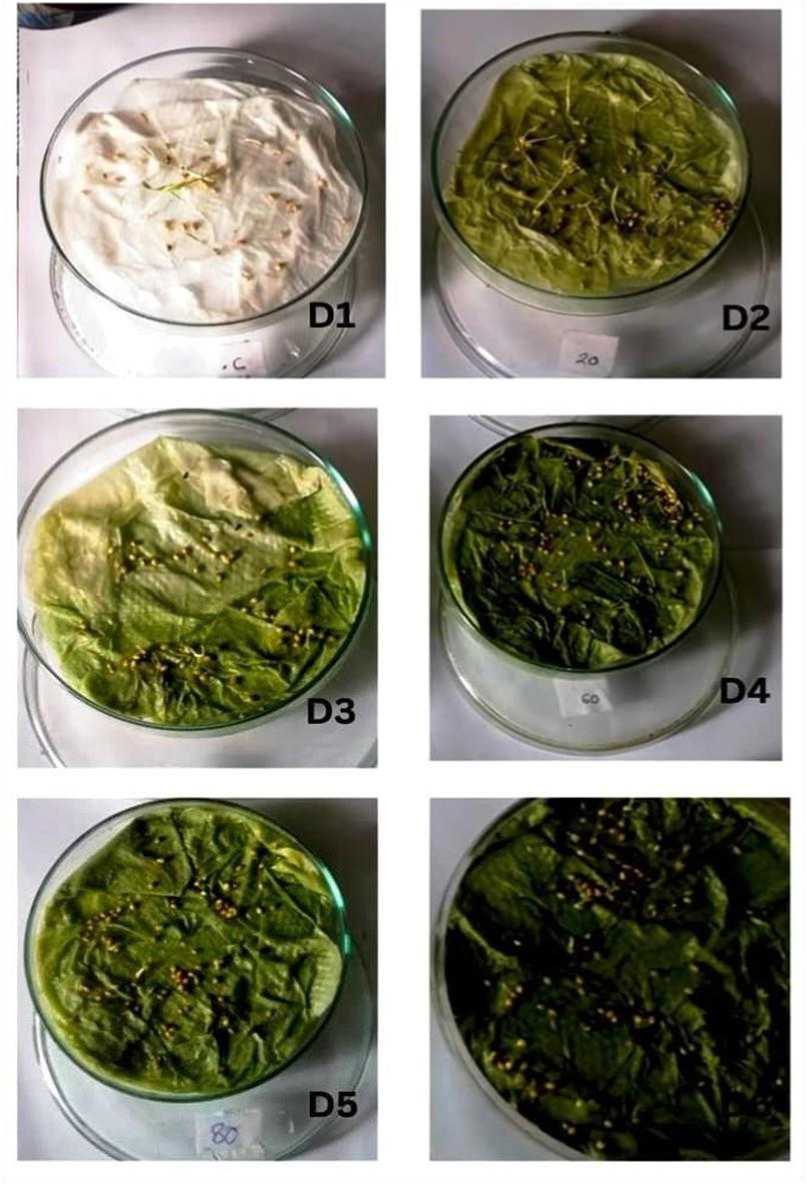

Figure 3: (d): Effect of Gliricidia sepium extract on Setaria italica seeds Day 2, D1- Control, D2-20%, D3-40%, D4- 60%, D5-80% and D6-100%

DISCUSSION

The study shows that the maximum seed germination was shown in the control where no extract used i.e. plant extract significantly suppressed the germination and the severity of effect was to proportional to the extract concentration. Increased concentration of extracts resulted in decreased germination rate, plumule formation and radicle formation.

The highest inhibitory effect was recorded in the 100% concentration solution, while the lowest was recorded in control solution. The "inhibitory" chemical is released into the environment where it affects the development and growth of neighboring plants. Allelopathic chemicals can be present in any part of the plant. They can be found in leaves, flowers, roots, fruits, or stems. They can also be found in the surrounding soil. Target species are affected by these toxins in many different ways. The toxic chemicals may inhibit shoot/root growth, they may inhibit nutrient uptake, or they may attack a naturally occurring symbiotic relationship thereby destroying the plant's usable source of a nutrient (Soni et al., 2017).Various other studies conducted elsewhere also revealed allelopathic suppression in soybean, maize and chilli (Sahoo et al. 2010). Melia azaderach, Morus alba and Moringa oleifera leaf leachates inhibited the germination, radicle and plumule growth of soybean (Kumar et al. 2009). Recent searches indicates that allele chemicals were universally present in plants and one of the most important physio- biochemical functions of them is defense against its enemies (Gavazzi et al. 2010) and suggests that early removal of these weeds, from the field is essential in order to avoid the losses in terms of poor germination and seedling vigor. There are several papers in which the allelopathic potential of aqueous plant extracts under field conditions in the most significant crops such as wheat, maize, or cotton has been investigated, presenting them with phytotoxic results expressed in terms of weed density and biomass reduction. Among the most common aqueous plant extracts used for weed control are sorghum and sunflower, which in concentration at 12 L ha -1 are efficient in limiting the dry weight of wild oats (Avena fatua L.) and canary grass (Phalaris minor Retz.), while at 6 L ha -1 is the most economically viable treatment. The authors of these applications recommended applying the extract directly to the soil or growing media to mitigate phytotoxicity on the above- mentioned crops. Summarizing the chemical effects induced in plants by the treatment of these extracts, the authors highlighted that there was a significant increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), suppression of the gibberellic pathway and accumulation of abscisic, salicylic and jasmonic acids, changes in cell membrane permeability and deregulation of nutrient uptake as well as modification of photosynthesis and respiration.

Allelopathic plant extracts and synthetic herbicides can be used together to reduce the application doses of these harmful ones. For more widespread application, it is crucial to understand the specific role of environmental factors on the bioavailability and effectiveness of allelochemicals. Environmental elements, mainly air and soil, act as carriers of allelochemicals, so pedoclimatic conditions can greatly influence the transport and retention of these compounds.

Regarding weed management in wheat crops, it was proven that the dose of Isoproturon could be reduced by as much as 60% following the application of a mixture of an aqueous extract of sorghum (Farooq et al. 2011). It was also discovered that the combination of an aqueous extract of sorghum and Pedimentalin at a dose equivalent to one-third of the standard amount resulted in a higher cotton yield than the application of the full dose of synthetic herbicide, even though weed suppression was relatively lower. Reduced doses of Pedimentalin were also combined with aqueous extracts from sorghum, sunflower, brassica, and rice demonstrating that 50–67% less herbicide in combination with allelopathic aqueous extracts can be effective in controlling weeds and increasing oilseed canola yields. Allelopathic Index of different concentrations of aqueous extract of Gliricidia sepium on seeds of red gram (Table 3) and that on seeds of foxtail millet (Table 4) are tabulated above. The negative value indicates strong allelopathic effect whereas positive values confirm absence of allelopathic effect of the tested extract.

As all the concentrations of the aqueous extract of Gliricidia sepium on seed germination of red gram and fox tail millet showed negative allelopathic index values. It is confirmed that the leaves of Gliricidia have an allelopathic effect on other crop plants such as red gram and foxtail millet.

CONCLUSIONS

The study concluded that leaves of Gliricidia sepium has allelopathic effect on the germination of seeds of crop plants studied ie. seeds of red gram (Vigna unguiculata) and fox tail millet (Setaria italica). The leaves of Gliricidia sepium has been used as a biological nitrogen fertilizer in crop fields from time immemorial. This effect of these leaves in inhibiting or slowing down the germination of other crop seeds can be utilized in bioweedicide preparation. Its potential to be used as a biofungicide or biopesticide also needs further investigation. Allelopathic effect of Gliricidia sepium leaves can also be used in targeting invasive plant removal from fields also. It could be a cheap, easy and environmental and human friendly option of a bio weedicide when compared to polluting and contaminating chemical alternatives. The study also concluded that it is effective in causing allelopathic activity in proteinaceous seeds such as pulses and carbohydrate rich seeds such as millets.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Allelopathy has been known and used in agriculture since ancient times; however, its recognition and use in modern agriculture are very limited. Allelopathy plays an important role in the control of weeds, diseases and insects. Furthermore, allelochemicals can act as environmentally friendly herbicides, fungicides, insecticides and plant growth regulators, and can have great value in sustainable agriculture. Although allelochemicals used as environmentally friendly herbicides has been tried for decades, there are very few natural herbicides on the market that are derived from an allelochemical. With increasing emphasis on organic agriculture and environmental protection, increasing attention has been paid to allelopathy research, and the physiological and ecological mechanisms of allelopathy are gradually being elucidated.

ACKNOWLEGEMENT

The authors express their gratitude to the research department of Botany, Union Christian College, Aluva for their support and encouragement during the study.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declare that he has no potential conflicts of interest.