Age-related features of preparing for old age: Population strategies in the context of implementation of state programs for older adults

Автор: Belekhova G.V., Popov A.V.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.18, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Against the background of global population aging and the transformation of public perceptions of old age, it becomes relevant to search for effective measures to ensure a high quality of life for the elderly. Of particular interest is the understanding of how the efforts undertaken by different socio-demographic groups to prepare for old age correlate with support measures and conditions created in the framework of state social policy for older adults (national projects “Older Generation” and “Long and Active Life”, strategy of actions in the interests of senior citizens in the Russian Federation, etc.). Thus, the aim of the work is to identify strategies for preparing for old age in different age groups. This will make it possible to trace the consistency of individual practices with the public policy, and to assess its potential and limitations. The empirical basis includes data from a sociological survey of the adult population of the Vologda Region (N = 1,500) conducted in January – February 2025. We use cluster and factor analysis methods to study the relationship between value concepts of a prosperous old age and strategies for preparing for it, as well as to establish age-specific features of their perception and formation. We find that good health, financial stability and family ties form the basis of subjective ideas about prosperous old age. Cluster analysis reveals the variability of their combinations, which indicates the absence of a single normative image of prosperous old age. We identify four main components that form strategies for preparing for old age: activity, labor, social, and health. It is proved that each age group chooses its own trajectories to prepare for old age. The revealed imbalances between the ideas of prosperous old age and the practices of achieving it indicate a low level of preparation for old age. The findings of the study provide materials for the development and revision of targeted social policy programs and national projects aimed at improving the quality of life at any age

Prosperous old age, strategy, social policy, clusters, health, labor activity, social ties

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147251536

IDR: 147251536 | УДК: 316.346.32-053.9:330.59 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2025.3.99.11

Текст научной статьи Age-related features of preparing for old age: Population strategies in the context of implementation of state programs for older adults

Modern social sciences consider old age not as a regular biological period, but as a dynamic and multidimensional social phenomenon formed by the interaction of individual strategies, cultural norms and structural conditions (Pavlova et al., 2021; Vidiasova, Grigoryeva, 2023). Old age, historically perceived as a time of near death, dependence, weakness and loneliness, is now perceived as a special period of life due to global population aging, adulthood of cohorts born in times of population explosion and increase in the required quality of life (Rogozin, 2012; Grigoryeva, Vidiasova, 2024). Within the “successful aging” and “active longevity” paradigms, widely represented in domestic and foreign works and often used as the conceptual basis of social policy toward the older adults in different countries, the elderly are positioned not only as recipients of assistance, but also as active subjects of social life and carriers of resources – social capital, professional experience, civic engagement. However, this progressive narrative faces persistent contradictions.

On the one hand, the value of maintaining productivity and autonomy in later life is declared, which implies maintaining physical and cognitive

Foundation grant 23-78-10128 function, and social integration (Rowe, Kahn, 1987; Kerschner, Pegues, 1998). On the other hand, stereotypes of helplessness and vulnerability of older people persist, exacerbated by agism in the labor market and in the public space. In particular, according to a “Romir” study, about 25% of Russians agree to some extent with the statement that “older adults are a burden for young people”1,2. Moreover, over half of the respondents faced cases of agism in their professional activities, including denial of jobs or forced retirement due to old age3. Moscow scholars, based on data from the 2022 initiative study “When does old age begin?”, emphasize that despite “the prevalence of values of respect for the elderly with a positive assessment of their contribution to society”, “there is a risk that a significant proportion of respondents have fixed negative stereotypes about the elderly, which not always correspond to reality” (Lyalikova et al., 2023, pp. 112–113). The image of old age developing in such a context reinforces normative expectations in the public consciousness, which subsequently have a regulating effect on the behavior of individuals (Anikina, Ivankina, 2019).

It is important to note that the growing awareness of the need to prepare for old age, fueled by the popularization of gerontological knowledge, does not lead to a massive transformation of behavioral patterns of this period of life. Sociological data show that only about a quarter of Russians (24%) are taking active steps to prepare for old age: they work a lot, make savings, and arrange housing4. Retirement savings remain a rare practice: only 16% of working Russians save for this purpose (mostly people aged 25–44, residents of Moscow, Saint Petersburg and million-plus cities)5. Current research (December 2024) also shows skepticism about the new long-term savings program: about one in five (22%) expresses a potential willingness to participate in it, but only 5% of them are ready to participate in the next 1–2 years, while the rest postpone the decision for 3–5 years6. This may indicate both low confidence in such initiatives or an intention to verify the effectiveness of the program, and the predominance of short-term priorities in individual planning. In terms of healthsaving behavior, the conclusions about the types of population by health-saving attitudes are indicative (Korolenko, 2021). The existence of a cluster “not motivated to take care of health, caring little or not caring at all, but recognizing personal responsibility for it”, which mainly consists of men aged 30–60 and women over 55 years old, and shows that many positive practices (abstinence from smoking, timely medical care, regular hours, healthy eating, sports, etc.) are ignored in this group (Korolenko, 2021).

The gap between the cognitive acceptance of the norms of healthy aging and their practical implementation is due to a set of objective and subjective constraints. The former ones include structural aspects: economic inequality, which hinders the use of pension, insurance, and investment tools, a shortage of affordable disease prevention programs, lack of legislative mechanisms to protect from agism, etc. Subjective constraints include socio-cultural and psychological factors: an inner belief in the irresistibility of age-related changes, a tendency to short-term planning, the perception of old age as a “period of natural decline”, the hope for family as the main source of support, as well as the conflict between individual values and dominant cultural scenarios.

National projects and government programs, such as “The Older Generation”, “Long and Active Life”, and the strategy of actions in the interests of senior citizens in the Russian Federation up to 2030, declare goals for developing the personal potential of older adults, maintaining their health, social inclusion, and financial stability. However, these initiatives often ignore the actual life strategies of citizens, which are formed under the influence of the limitations outlined above. These programs do not take into account spatial inequality: access to high-quality medicine, educational courses for the elderly, and digital services is sharply reduced outside of large cities and has restrictions depending on the region. There is a contradiction between the normative prescriptions “how to age correctly and successfully” and the everyday practices of the population, which in many ways turn out to be reactive, being a response to crises, rather than the result of conscious planning. In such circumstances, the concepts of active longevity and successful aging promoted by the state can remain a rhetorical construct unrelated to the real lives of most citizens.

All government initiatives imply that prosperous old age is formed in the context of “a life perspective that considers the influence of experience gained in the early periods of life on the nature of human aging in the future” (Golubeva, 2015, p. 635; Korolenko, 2022, p. 5), which means that old age ceases to be predetermined, and its construction increases request for individual training and provision of necessary conditions for the implementation of life strategies. This requires a review of social policy aimed not only at promoting “correct” practices, but also at removing systemic constraints that turn agency into the privilege of educated and economically stable segment. Understanding these processes is necessary to predict future scenarios where old age can become both a period of realization of accumulated capital and a period of marginalization, aggravated by the inability to adapt to the speed of technological and social changes.

Consequently, the research issue lies in the contradiction between the universality and inevitability of old age as a life period and the heterogeneity of ways of preparing for it, due to the socio-cultural, economic and institutional features of Russia. Despite the general understanding of the need for advance planning, as well as the implementation of national projects and programs such as “The Older Generation”, “Long and Active Life”, strategy of actions in the interests of senior citizens in the Russian Federation, etc., Russia is characterized by a significant gap between the declaration of the importance of health, financial independence, labor or other activity, social inclusion in old age and the actual behavior of the population. This contradiction requires an analysis of individual life strategies.

In this regard, the aim of our study was to identify strategies for preparing for old age in different age groups based on the analysis of the relationship between their concept of “prosperous old age” and actual practices of preparing for it. This will allow tracing the consistency of individual practices with the measures of public policy, assess their potential and limitations in supporting the population. The logic of the study involves determining the dominant values of “prosperous old age” in Russian society (using the example of the Vologda Region), analyzing strategies for preparing for old age with the emphasis on their prevalence in different age groups, identifying gaps between values and behavior by distinguishing the points where the declared goals are not transformed into actions (for example, the high importance of “health in old age” with disregard of preventive measures and healthsaving practices).

Such studies are important for government authorities, social institutions, non-profit organizations, and other agents working with the elderly, because identifying “gaps” between stated goals (for example, “I want to be healthy in old age”) and actual practices (lack of savings, low physical activity, disregard of therapy for chronic diseases) will help develop targeted management actions. In addition, the findings will contribute to the development of research on prosperous old age and strategies for achieving it based on studying old-age-related preventive practices and values.

Literature review

In numerous socio-gerontological studies of old age, one of the most discussed paradigms is successful aging, which was introduced into scientific community in the 1960s by R. Havighurst. An American lecturer and researcher in the field of psychology and sociology of aging held the view of the natural scenario of the relationship between an elderly and society and defined “successful aging” as an inner feeling of happiness and satisfaction with present and past life (Havighurst, 1963). Subsequently, as part of the evolution of gerontological approaches, such areas as healthy aging (physical health and disability prevention), active aging (continued work and social engagement), productive aging (long-term employment as a benefit to society), positive aging (subjective perception of old age as a period of opportunities), etc. (Evseeva, 2020). Despite the terminological differences, all these models share a focus on achieving an optimal aging scenario that combines objective indicators (physical health, social activity) and subjective life satisfaction (Belekhova et al., 2024).

Empirical studies based on these theories identify such key components of the life strategies of the elderly as work providing identity and economic stability, health care through prevention and management of age-related changes, as well as social inclusion aimed at maintaining connections and overcoming isolation. The analysis of such strategies is carried out both retrospectively through the lens of biographical experience and in the context of current practices using sociological surveys, which allows us to take into account the diversity of aging trajectories depending on cultural, economic and individual factors.

In many foreign works, the study of behavioral practices in old age is based on the concept of successful aging by Rowe and Kahn, who developed the ideas of R. Havighurst. Within this concept, the analytical model of aging strategies is determined by a combination of components such as the absence of disease and disability, as well as difficulties in performing daily activities, high cognitive function, and active social engagement (Rowe, Kahn, 1987). Based on data from national surveys of several Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea; 6479 participants aged 65 to 75 years in total) conducted in 2008–2011, it was found that the proportion of older adults who fully met the criteria for successful aging was less than a fifth of the sample (17.6%) (Nakagawa et al., 2021). Generalized and country-specific indicators of successful aging varied within and between countries, even after taking into account individual socio-demographic factors (age, gender, and education). The analysis showed that the chances to successfully age were highest in Japan and lowest in China, especially in rural areas. In addition, younger age and male gender increased the likelihood of successful aging (Nakagawa et al., 2021). Based on the results of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) for 1998–2004, American scientists assessed the prevalence of the successful aging among older Americans (65 years and older) and showed a decrease in its prevalence over time, including after considering individual socio-demographic factors (age, gender, education and ethnicity) (McLaughlin et al., 2010). Such results indicate the significant role of macro-level social factors (health and social protection system, economic conditions) in ensuring successful aging, which is also confirmed by the conclusions based on the data from the Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), conducted in 2004–2007 in Israel and 14 European countries based on a sample of the population aged 65 years and older (Hank, 2011).

Other studies of life strategies in old age, carried out by foreign authors, reveal the complex relationship between the subjective perception of aging, the stability of personality patterns and available resources. The work of Keller and his colleagues (Keller et al., 1989), based on indepth interviews with 32 adults aged 50–80 years, demonstrated the paradoxical perception of old age: despite the predominance of negative associations with age-related changes (loss of health, loss of loved ones), the majority of respondents assessed this period as positive. Effective coping strategies, including compensation for limitations, stress management, maintenance, social engagement, and changes in life orientations, have become key factors in this contradiction (Keller et al., 1989). At the same time, there are five models of positive and negative aging experiences:

-

1) aging as a natural and gradual process without remarkable features;

-

2) aging as a period of life evaluation, philosophical reflection;

-

3) aging as a period of increased freedom, new interests, and fewer demands;

-

4) aging as a period associated with physical health difficulties;

-

5) aging as a period of losses, both interpersonal and job related.

The key message of the paper, which is in the fact that subjective well-being in old age is formed not by the absence of problems, but by the ability to cope with them through internal activity, laid the foundation for studying aging as a process controlled by personal resources.

A longitudinal study by Coleman and coauthors (Coleman et al., 1998) complemented these findings by revealing the persistence of life themes in old age. Scholars have shown that family relations, the desire to maintain independence in everyday life and own home are central elements of the identity of older people, even in conditions of physical and social limitations. Further studies of life strategies in old age once again showed the multidirectional nature of aging, consisting in the connection between positive and negative characteristics of this period, and also confirmed the link between individual resources (health, income, education, social ties, etc.) and the perception of aging. For example, a high subjective assessment of health and a low level of loneliness shift the focus from physical decline, reinforcing a positive perception of personal growth and selfempowerment (Steverink et al., 2001).

The reviewed foreign studies allow us to identify two complementary aspects of the development of life strategies in old age. On the one hand, they reflect the persistence of basic life values, on the other, they require flexible adaptation to changing conditions through resource mobilization. Thus, understanding personal resources and capabilities becomes a key factor in effectively addressing the problems of aging and forming successful coping strategies that ensure a high level of subjective wellbeing in old age.

The Russian scientific tradition has also accumulated a significant amount of theoretical and applied works on the image and lifestyle of older people, strategies for their social behavior and problems of adaptation to modern conditions. Some of the studies are based on the conceptual foundations of the active longevity paradigm. In particular, based on a 2023 survey of senior citizens of the Sverdlovsk Region over 60 years old (417 people), it was found that active longevity for people of the Urals is primarily associated with maintaining health (90.7%), physical activity (66.9%), confidence in the future (38.1%), communication and social relations (27.8%) (Kas’yanova et al., 2023). Such social roles as “mentor”, “parent”, “friend”, and “enthusiastic person engaged in what they love” are identified as the most typical for the elderly. Older people of the Urals are aware of the importance of different types of activity, but they are poorly implementing them in practice. Also, many of them do not try to plan their activities for the future: plans are limited to a week or a month. The preferred activities of older adults are those for their own pleasure (hobbies) and to keep fit, paid for mainly with their own funds (Kas’yanova et al., 2023).

Another example of studying old-age-related life strategies within the concept of active longevity is a study conducted by scientists from Vologda Research Center of RAS. According to the sociological survey “Active longevity and its factors” conducted in 2021 in the Vologda Region, respondents named maintaining good health throughout their lives as a key component of active longevity (53%), while maintaining social ties took the second position (31%), the possibility of long-term work – the third (25%). The practices of self-development, education, and hobbies were given low priorities (Korolenko, 2022). At the same time, almost one in five (18%) does not take aimed actions to maintain a long and active life, and among the measures implemented, the most common are maintaining family relations and regular communication with friends. Healthsaving practices such as physical activity, proper diet, stress management, abstinence from bad habits, and trips to doctors are even less common. The study highlights the main contradiction: the expressed attitudes toward active longevity among the inhabitants of the region do not transform into systemic actions. Measures to maintain health, which is given top priority among values, are actually less frequent than those to maintain social ties (Korolenko, 2022).

In the socio-psychological research, the authors identify several strategies for adaptation in old and very old age – a closed-loop strategy, which means preserving oneself as an individual, and an alternative strategy, which means preserving oneself as a person. It is noted that women’s and men’s adaptation to old age has specific differences due to gender-specific lifestyle features: men identify themselves as specialists in their area, while women more often associate themselves with family responsibilities and household management (Dvoryanchikov, Sokolinskaya, 2017).

In studies on the life strategies of the elderly, special attention is paid to the role of work as a key factor of adaptation in a post-industrial society. This “work-oriented approach” is implemented in a study within the project “Peculiarities of employment and career of the elderly in modern Russia”, based on the 2022 all-Russian survey of pensioners (55–59 years old; 60–65; 66–74; 75+) from 71 constituent entities. Two basic life strategies of pensioners have been identified: active – orientation toward continuing to work (typical for those who work and plan to continue working, as well as for those who do not work but are seeking to find work); passive – orientation toward life without work (typical for those who have completed their work or plan to complete it) (Barkov et al., 2022). The choice of an active strategy correlates with gender, age, and educational characteristics: it is more often followed by men, relatively young respondents, and people with higher education. The study found that women are guided by social motives (the desire to avoid loneliness) and passion for the profession, while for men over 65 it is important to work because it is their habit. It is separately noted that pensioners with high incomes (for example, if they are helped by their children) consider work primarily as a tool for self-realization, which emphasizes the link between economic stability and the possibility of choosing meaningful practices (Barkov et al., 2022).

A similar logic is found in the works of Penza researchers who, based on data from their interregional surveys of pensioners (2018–2019) and employers (2018), studied the behavioral practices of older people associated with improving well-being (Shchanina, 2021). The typology was based on the nature of social activity. It was determined that 66% of elderly people implement active behavioral practices, and 34% – passive ones. At the same time, active practices are divided into constructive and reactive ones. In constructive behavioral practices, an elderly person either influences the social environment, or realizes his or her potential through creative activities and new forms of social interaction, or maintains current social ties without changing the environment. In reactive practices, older adults try to compensate for losses and reduce the damage caused by retirement age. The paper shows that among the most common practices aimed at improving one’s well-being, in addition to receiving a retirement pension, include work, financial behavior, and self-sufficient farming in order to generate additional income. At the same time, the level of activity of pensioners varies and is determined by the number of simultaneously selected and implemented practices (Shchanina, 2021).

Leaving aside the “life strategy” concept and a large number of synonymous terms (model, attitude, behavioral practices, etc.), we note that a very apt definition of life strategy in old age is presented in the study (Budyakova et al., 2024): life strategy is a general plan in line with a goal that is vital for the functioning and development of a person, which requires the mobilization of resources both of previous ages and current to ensure a safe comfortable life of older adults. The authors of this study used biographical, autobiographical methods and meaningful content analysis to research the life strategies of older people. The analysis was carried out on biographies of famous personalities and information from websites where the problems of the elderly are actively discussed. Such strategies as work, family, home/dacha, sports, hobbies, religion and sacrifice were identified and described. It is determined that the leading activity of older adults is work. However, the work strategy cannot be implemented by everyone in old age for a number of objective reasons: job specifics, state of health, requirements of employers, regulatory restrictions, etc. The researchers emphasize that positive strategies for living in old age should meet a number of conditions:

-

1) be meaningful;

-

2) continue the general logic of personality development in ontogenesis, so there should be conscious preparation for this period of life;

-

3) include different activities, at least one of which should be leading and influence all others, give them meaning;

-

4) be developed ensuring security of the individual, allowing to preserve dignity and selfrespect in old age, to resist agism (Budyakova et al., 2024, pp. 102–103).

In our opinion, prosperous old age as an optimal future life is based, on the one hand, on favorable objective living conditions (environmental factors), on the other hand, on the development and implementation of appropriate individual attitudes and behavioral practices (an individual’s attitude). The present study is characterized by the use of specialized methodological tools. Using survey data structured around a cluster of questions about old age, we focus on its perception as a separate period requiring preparation. Respondents are gradually guided from common associations (“What is prosperous old age?”) to specific practices (“What do you currently do to achieve it?”), which allows identifying not only the declared values, but also the gap between them and everyday actions.

Data and methods

The research is based on data from the sociological survey “Population well-being” conducted by Vologda Research Center of RAS in January –

February, 2025. Data were collected with a handout survey of adults of the Vologda Region in the cities of Vologda and Cherepovets, and in eight municipal districts. The sample size was 1,500 people. The sample is representative, quota controlled by gender (men, women), age (18–24 years old, 25–34 years old, 35–44 years old, 45–54 years old, 55–64 years old, 65–74 years old, 75+ years old), economic activity (employed, unemployed, economically inactive). The sampling error is no more than 3–4%.

The logic of the paper is based on the study of the relationship between subjective ideas about prosperous old age and strategies for preparing for it in various age groups. The first part is devoted to identifying the key components of prosperous old age. To substantiate the complexity of the issue, in addition to frequency distribution of features, cluster analysis was applied, which allowed us to identify various combinations of opinions and determine the priority of components. In the second part of the paper, attention is paid to strategies for preparing for prosperous old age. Based on the data obtained on its perception, a descriptive and factorial analysis of the practices that people use to improve their lives in old age was carried out. An emphasis is on the search for age differences in behavioral strategies: from professional selfrealization among young people to health care and social activity in more mature groups. The last part examines the influence of the subjective perception of prosperous old age on the choice of strategies to achieve it. For this purpose, as in the previous part, the factor weights of the components of preparation for prosperous old age are assessed by age groups of the population.

Findings

The perception of prosperous old age

The starting point for the study was to explore what people mean by prosperous old age ( Tab. 1 ). According to the survey results, it is viewed mainly through the lens of good physical and mental

Table 1. Distribution of answers to the question “What does prosperous old age mean to you?”* by age group, %

|

Answer options |

Age, years |

Mean |

||||

|

18–24 |

25–34 |

35–54 |

55–64 |

65+ |

||

|

Good physical and mental health |

83.6 |

77.7 |

75.0 |

71.6 |

76.5 |

75.8 |

|

Financial stability and adequate pension |

62.3 |

70.5 |

65.5 |

63.1 |

66.8 |

65.8 |

|

Access to high-quality medical services |

56.6 |

57.3 |

53.9 |

50.9 |

54.2 |

54.1 |

|

Good relations in the family and with relatives |

54.9 |

47.3 |

47.9 |

52.8 |

51.1 |

49.9 |

|

Convenient and safe housing |

46.7 |

32.3 |

35.4 |

36.5 |

37.9 |

36.6 |

|

Friends and a pleasant social circle |

35.2 |

31.4 |

29.9 |

33.6 |

27.6 |

30.7 |

|

The opportunity to live comfortably and not work |

37.7 |

28.6 |

26.8 |

21.0 |

21.9 |

25.9 |

|

Social security and access to legal aid |

18.0 |

23.6 |

22.0 |

19.9 |

20.7 |

21.3 |

|

Absence of loneliness and isolation |

23.8 |

16.4 |

16.0 |

17.7 |

23.2 |

18.5 |

|

The opportunity to do what I love, hobbies |

23.8 |

18.6 |

13.0 |

17.0 |

11.9 |

15.2 |

|

The opportunity to continue working |

11.5 |

9.5 |

10.2 |

10.3 |

5.6 |

9.3 |

|

A feeling of importance to society, family, and friends |

13.1 |

7.7 |

9.2 |

8.5 |

6.3 |

8.5 |

|

Respect from others |

17.2 |

8.2 |

6.2 |

8.5 |

7.5 |

8.1 |

|

Participation in social and cultural life |

8.2 |

5.5 |

5.8 |

6.6 |

5.3 |

6.0 |

|

Absence of agism |

6.6 |

4.5 |

5.1 |

5.9 |

6.6 |

5.6 |

* Respondents were allowed to choose no more than 5 options.

Note: the main components of prosperous old age that will be used in further analysis are highlighted in gray; the data are ranked by the last column of the table.

Calculated based on: data from the 2025 sociological survey of adults of the Vologda Region “Population well-being”, Vologda Research Center of RAS.

health (76%), financial stability and adequate pension (66%), access to high-quality medical services (54%), good relations in the family and with relatives (50%). Since the respondents were offered to choose up to five possible answers, we can highlight convenient and safe housing, which was considered as important by over a third (37%) of them. All other components of prosperous old age are much less significant. In particular, issues related to agism (6%), participation in social and cultural life (6%), and respect (8%) are on the periphery of public opinion. Based on this, prosperous old age is perceived primarily as a high physical and cognitive functional capacity, security, financial prosperity and stable family ties, which, in the aggregate, allows meeting basic human needs and therefore has much in common with traditional ideas about a decent life (Smoleva, Morev, 2015).

It is interesting that estimates of the main components of prosperous old age do not dramatically change by age groups. As a rule, young people get the highest share, for example, in choosing good physical and mental health, or convenient and safe housing. The latter aspect particularly stands out among people aged 18 to 24, which once again indicates the acuteness of the issue of acquiring own real estate (Savenkova, 2022). Using a broader list of characteristics of prosperous old age does not significantly improve the overall picture. For younger people, the importance of being able to live comfortably and not work, have hobbies and get respect from others is more pronounced. At the same time, the absence of loneliness and isolation is equally emphasized not only by the youngest, but also by the oldest age group.

In the process of studying the subjective perception of prosperous old age, it should be remembered that its content is determined by a set of various components that combine with each other depending on individual ideas and life experience of a person, the socio-cultural context, thereby forming an integral, but very heterogeneous image. This is clearly demonstrated in Table 2 , which shows the results of cluster analysis. The respondents’ responses were used as initial data, characterizing agreement (1) or disagreement (0) with the five key components of prosperous old age. Clusters were based mainly on two of them: convenient and safe housing (1.00), as well as good physical and mental health (0.77).

Table 2. Characteristics of clusters created based on the distribution of answers to the question “What does prosperous old age mean to you?”

|

Cluster |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

Share |

15.7% |

15.7% |

17.5% |

19.1% |

19.4% |

12.6% |

|

Input field (predictor significance) |

Convenient and safe housing (1.00) |

|||||

|

0 (100.0%) |

0 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

0 (100.0%) |

0 (100.0%) |

|

|

Good physical and mental health (0.77) |

||||||

|

0 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

1 (55.4%) |

1 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

|

|

The most common response option (percentage of respondents who have chosen it) |

Financial stability and adequate pension (0.52) |

|||||

|

0 (51.5%) |

0 (100.0%) |

1 (79.0%) |

1 (64.8%) |

1 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

|

|

Good relations in the family and with relatives (0.37) |

||||||

|

0 (63.8%) |

0 (62.7%) |

1 (61.8%) |

1 (57.1%) |

1 (100.0%) |

0 (100.0%) |

|

|

Access to high-quality medical services (0.28) |

||||||

|

0 (64.7%) |

1 (52.1%) |

1 (100.0%) |

0 (80.5%) |

1 (67.4%) |

0 (51.3%) |

|

Note: since binary categorical variables were used in the cluster analysis, gray cells indicate that the most common category is 1. Calculated based on: data from the 2025 sociological survey of adults of the Vologda Region “Population well-being”, Vologda Research Center of RAS.

The optimal number of clusters was estimated with the Bayes information criterion. As a result, six stable clusters with internal consistency and differentiation were identified. All of them have approximately the same share, which varies from 13 to 19%. The silhouette value of cohesion and separation is in the middle zone (0.4), which indicates an acceptable quality of the model: the resulting clusters are distinguishable, although not completely clearly separated from each other, they make it clear how the selected components of prosperous old age intersect.

The analysis showed that the health factor is given top priority in the public perception of prosperous old age. It occurs in all clusters, with the exception of cluster 1, where negative responses dominate in all the considered positions. The importance of financial stability and adequate pension is also almost universally noted (except for clusters 1 and 2). The remaining components of prosperous old age are rarer, and they variously combine with each other. As a result, the content of the clusters is rather vague. Excluding cluster 1, we can observe that the number of components of prosperous old age ranges from two (focus on health and financial prosperity or health and medical care) to all five. Such a variety of meanings prevents the unambiguous interpretation of clusters and, consequently, their use in further work.

Strategies for preparing for prosperous old age

Obviously, depending on a person’s age, strategies for preparing for prosperous old age will change. For some, they may be influenced by idealized pictures of distant future, while for others, they may be related to current living conditions. Exploration of these features requires the use of additional methods to reduce the set of options as characteristics of individual behavioral patterns to a small number of meanings. One of these tools is the factor analysis, which we applied to the question of actions to achieve prosperous old age using principal components analysis and orthogonal rotation (varimax with Kaiser normalization). A pre-check showed that the sample is suitable for factorization7.

Four components were extracted, reflecting integrated strategies for preparing for prosperous old age and explaining 66% of the total variance ( Tab. 3 ). Based on the meaning of variables and factor weights, the components received the following symbols:

– activity component: combines practices aimed at internal development, financial independence, psychological stability and cultural

-

7 The data were pre-checked before performing factor analysis. The measure of sampling adequacy according to the Kaiser – Meyer – Olkin test was 0.857, which indicates a high degree of its suitability for factorization. In addition, the presence of significant correlations between variables and the validity of the use of factor analysis are confirmed by the results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity ( χ 2 = 10533.534; df = 136; p < 0.005).

Table 3. A rotated matrix of components created based on the distribution of answers to the question “What do you currently do to achieve prosperous old age?”

Answer option (variable)

Component name

activity component

work component

social component

health component

I am engaged in spiritual practices (meditate, pray, train mindfulness)

0.775

I create my own sources of passive income (purchase real estate for rent, invest, purchase securities)

0.767

I prepare mentally and psychologically: learn to understand myself better, work on positive thinking, deal with my psychological struggles and traumas

0.763

I am engaged in public life (environmental actions, book club, solving household issues together with other owners, etc.)

0.756

I save up for a living in old age

0.708

I visit cultural institutions (theaters, cinemas, libraries)

0.619

I use modern technologies to prolong and maintain youth and health (for example, cosmetology)

0.447

0.400

0.432

I improve my professional qualifications

0.823

I gain continuous working experience

0.817

I try to work officially with a salary reported for tax

0.693

I get additional education

0.463

0.636

I try to get state awards that guarantee benefits and pension increase

0.488

0.562

I maintain cognitive activity

0.416

0.410

I maintain good relations with family members

0.873

I regularly communicate with friends and acquaintances

0.870

I try to avoid stress

0.860

I take care of my health (visiting doctors, eating, sleeping, exercising)

0.845

Note: gray color indicates the cells with the largest contribution of the variable to the corresponding component; coefficients with values over 0.4 are displayed.

Calculated based on: data from the 2025 sociological survey of adults of the Vologda Region “Population well-being”, Vologda Research Center of RAS.

activity, which may indicate a conscious preparation for prosperous old age;

– work component: focuses on actions related to professional self-realization, proposes that prosperous old age is a result of continuous and uninterrupted working experience;

– social component: focuses on the importance of interpersonal relations, since prosperous old age largely depends on stable and deep social connections;

– health component: focuses on taking care of physical and psycho-emotional health, which emphasizes the importance of supportive practices in ensuring active longevity and prosperous old age.

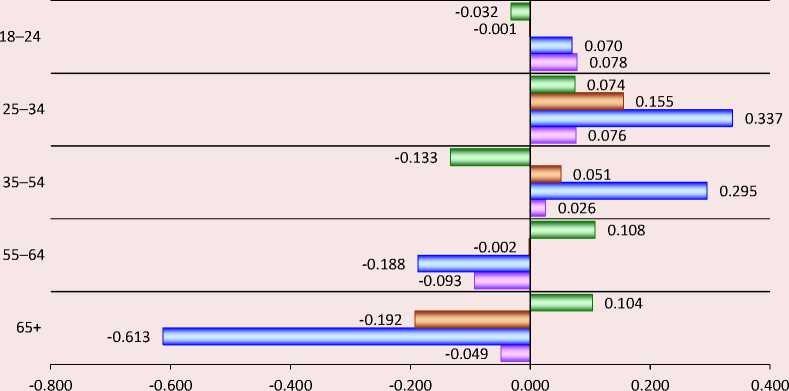

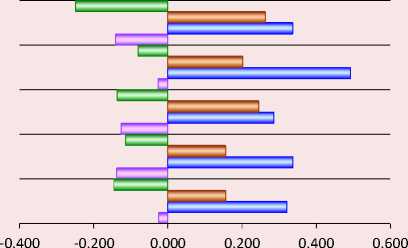

Later, the selected components were used to combine with age groups in order to track changes in behavioral patterns ( Fig. 1 ). For this, average factor scores for each component were calculated, which could take both positive and negative values: the former indicated a clearer manifestation of the related strategy for preparing for prosperous old age, whereas the latter indicated a lesser degree of manifestation. The results of the analysis vividly showed how priorities for living change with age.

Figure 1. Factor weights of the components of preparation for prosperous old age by age groups

health component social component work component activity component

Calculated based on: data from the 2025 sociological survey of adults of the Vologda Region “Population well-being”, Vologda Research Center of RAS.

Young people aged 18–24 try to achieve prosperous old age primarily through professional self-realization and various activities, while issues of health and interaction with loved ones are on the periphery of everyday practices. An older group (25–34 years old) is characterized by an increased share of the work component, reaching its maximum among all ages, which emphasizes the importance of career development as a key strategy for well-being in old age. The activity component maintains high levels, while the importance of health and social ties begin to grow, though remaining on the periphery.

In mature age (35–54 years old), the orientation toward professional self-realization continues to dominate, although its influence is reducing. The range of proactive life strategies and the frequency of interpersonal contacts are noticeably lower, while the health component value becomes negative, which indicates changes for the worse in self-preservation behavior. In the next age group (55–64 years old) the situation is changing dramatically. The only component in the positive area is health, the care of which can be perceived as a key direction for maintaining the quality of life in conditions of decreasing importance of work and reducing social activity in general.

The age group over 65 is characterized by the development of the previously outlined trends. The work component shows the greatest negative value, obviously indicating career ending. The focus remains on taking care of the physical and psycho-emotional health. Also, while the activity component is even growing slightly, the social component shows a sharp drop, which may be due to a natural reduction in the range of social ties, including due to the loss of loved ones. Thus, with age, the hierarchy of strategies for preparing for prosperous old age changes from focusing on activities and professional self-realization in youth to increasing attention to health in old age.

The results of the analysis demonstrate a dynamic transformation of strategies for ensuring prosperous old age, which reflects both age-related changes in priorities and contradictions between the ideas of successful aging and the actual possibilities of their implementation. In youth, the dominant attitude is toward active future building through professional self-realization and multitasking, which corresponds to the concepts of active longevity and successful aging, emphasizing continuous development and social inclusion. However, the hyperfocus on career and productivity in middle age (25–54 years old) is accompanied by less attention to health and social connections, which contradicts the basic principles of successful aging (Rowe, Kahn, 1997), requiring a balance between physical, cognitive and social well-being. After 55 years of age, health becomes the only supported component, while work and social strategies lose their importance. This may indicate that the idea of remaining active in all areas of life inevitably faces the realities of age restrictions and objective losses (narrowing social circle, career ending, decreasing health potential), which in turn imposes restrictions on the universality of the paradigms of active longevity and successful aging. The collected data emphasize that social programs supporting the elderly should take into account the non-linearity of life trajectories, rather than using a single pattern like active longevity or successful aging, and develop flexible solutions that support health as the basis of the well-being in old age and create conditions for the reestablishment of social ties and alternative forms of self-realization after retirement.

The influence of subjective perception of prosperous old age on strategies for preparing for it

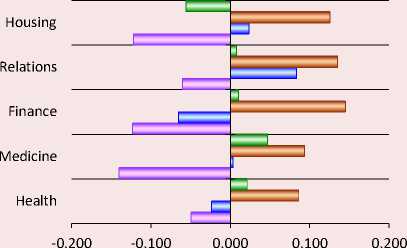

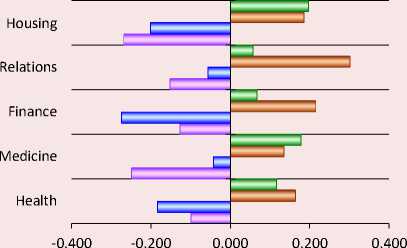

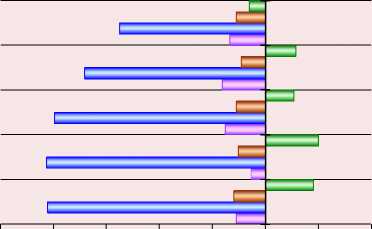

In addition to age characteristics (including generational), strategies for preparing for prosperous old age depend on how it is viewed by people. Previously, we identified five main components of it: good physical and mental health, financial stability and adequate pension, access to high-quality medical services, good relations with family and relatives, comfortable and safe housing. To make their indication more straightforward, they were further referred to as “health”, “finance”, “medicine”, “relations” and “housing”. The predominance of one or another vision of prosperous old age, despite the complexity of combining different perspectives, as demonstrated by cluster analysis, should have an impact on behavioral patterns. The assessment of factor weights fully confirms this thesis, although in some cases it is problematic to explain the results ( Fig. 2 ).

The example of the aggregated population clearly shows how the perception of prosperous old age through the lens of health or medicine leads to pronounced self-preservation behavior strategies. However, such positive relationship is not observed when it comes the emphasis on financial prosperity and professional self-realization. It would be logical to expect that in such a situation people would put efforts into accumulating resources through hard work, but actually such correlation is very rare and often occasional. At the same time, prosperous old age viewed as good relations with family and relatives is closely linked to work, which is hardly obvious. Such a bias can be caused both by the limitations of the methodological tools used and by the specifics of cognitive processes. In particular, the inclination toward short-term goals, as well as systematic errors in predicting the future, can disrupt the integrity of the perception of ways to achieve prosperous old age, reducing the consistency and stability of appropriate behavioral attitudes.

Figure 2. Factor weights of the components of preparation for prosperous old age, considering its subjective perception by age groups

Aggregated population

18–24 years old

-0.200 -0.100 0.000 0.100 0.200 0.300

|

□ health component |

□ social component |

|

□ work component |

□ activity component |

-

□ health component

-

□ work component

-

□ social component

-

□ activity component

25–34 years old

35–54 years old

Housing

Relations

Finance

Medicine

Health

-0.200 0.000 0.200 0.400 0.600

|

□ health component |

□ social component |

|

□ work component |

□ activity component |

-

□ health component

-

□ work component

-

□ social component

-

□ activity component

55–64 years old

65+ years old

-1.000 -0.800 -0.600 -0.400 -0.200 0.000 0.200 0.400

-

□ health component

-

□ work component

-

□ social component

-

□ activity component

-

□ health component

-

□ work component

-

□ social component

-

□ activity component

Calculated based on: data from the 2025 sociological survey of adults of the Vologda Region “Population well-being”, Vologda Research Center of RAS.

Subjective ideas about prosperous old age have the least impact on the strategies of people over 35 years of age. The average factor scores for each component here do not change their sign and differ by several tenths. The only exception is the oldest group, in which the perception of prosperous old age as comfortable and safe housing causes a decrease in health indicators. The main changes relate to young people, which underlines the need for in-depth analysis to identify more well-founded patterns and a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of influence of ideas about prosperous old age on strategies to achieve it in different age groups. In further research, additional factors will be considered that allow clarifying the observed differences and conclusions drawn.

Nevertheless, the present study clearly demonstrates the inconsistency between subjective ideas about prosperous old age and actual (declared) strategies for preparing for it. The fact that the emphasis on health and access to high-quality medical care is reflected in self-preservation behavior, while the focus on financial prosperity is hardly translated into active accumulation of resources, indicates the difficulty of materializing existing ideals into behavioral practices (for example, people tend to declare the importance of financial stability, but are not always willing to sacrifice current comfort for the sake of long-term goals). It is significant that subjective beliefs have little effect on life strategies for people over 35 years of age. This suggests that in mature age, the goals become less flexible, and attempts to change behavior encounter developed habits and limited resources. The collected data emphasize that the concepts of successful aging and active longevity, which involve conscious future building, face constraints due to both thinking patterns and structural barriers (environmental features, limited personal resources). Social programs aimed at supporting prosperous old age should take into account this duality and not only promote long-term planning, but also create an environment that minimizes the gap between intentions and actions.

Conclusion

Aging and reaching retirement age represent special period of life, accompanied by a transformation of social roles, a revision of priorities and the need to adapt to changing living conditions. These processes involve not only the development of new attitudes, such as health care or maintenance of social ties, but also the restructuring of behavioral strategies in response to changes in age, physical and status characteristics of a person.

The conducted research revealed the key features of the development of life strategies of different age groups aimed at preparing for prosperous old age (using the example of latest empirical data on the Vologda Region). It was found that good physical and mental health (76%), financial stability (66%), access to high-quality medicine (54%) and stable family ties (50%) form the basis of subjective ideas about prosperous old age. Housing conditions, despite their importance for young people (37%), remain supplementary, while issues of social engagement and agism are on the periphery (6–8%). Cluster analysis confirmed the dominance of health and financial security in the structure of perception, but revealed significant variability in their combinations, which indicates the absence of a single normative image of old age in the public consciousness.

The identification of four key components of preparation for prosperous old age: activity, work, social component and health – helped to understand the structure of strategies for preparing for it. Young people (18–34 years old) are characterized by a focus on professional self-realization and various activities (professional development, financial planning), while health care and social connections become relevant in mature age (35–54 years old). In the group of people aged 55–64, the emphasis on health care dominates, and for people over 65, the decrease in work and social activity is compensated by increased attention to physical and psycho-emotional health.

The relationship between the subjective perception of prosperous old age and the actual preparation practices turned out to be ambiguous. While the focus on health and access to medicine correlates with self-preservation behavior, the attention to financial well-being does not lead to systematic actions in the field of finance and employment. An unobvious relationship has been established between the importance of family relations and work activity, which may reflect the compensatory nature of employment as a way of maintaining social ties. It has been revealed that ideas about prosperous old age have a minimal impact on the actual strategies for people over 35 years old, which casts doubt on the ability of educational resources and outreach materials to influence changes in the behavior of the population. In general, these data confirm the occasional nature of long-term planning, which is often developed as a response to current challenges rather than as a conscious strategy.

Russia’s state policy toward the older generation is represented by a set of initiatives, including the national project “Long and Active Life”, aimed at ensuring access to high-quality medical care, disease prevention and timely rehabilitation, including in remote and sparsely populated areas of the country, and the “Strategy of Actions in the Interests of Senior Citizens up to 2030”, which is aimed at growth in prosperity and life expectancy of senior citizens. This policy comprehensively covers key areas of well-being – health protection and active longevity, strong family values and respect for the elderly, conditions for the realization of personal potential and social participation, a system of social services and comfortable infrastructure, increasing financial security of the elderly – and thereby creates an institutional environment designed to minimize structural barriers to decent life in old age. However, the findings of this study, revealing significant variability in subjective perceptions of prosperous old age and heterogeneity, often occasional, of actual strategies for preparing for it at different ages, as well as persistent gaps between values and practices, emphasize the difficulty of achieving full harmony between policy goals and the diversity of individual life trajectories. Consequently, effective promotion of prosperous old age requires government social programs not only to create common institutional conditions, but also to develop flexible solutions adapted to the age specifics and actual practices of the population, with an emphasis on supporting health as a foundation and creating opportunities for various forms of social inclusion and self-realization in old age.

The findings underscore the need to consider age-related and structural constraints (economic, territorial) when developing programs aimed at supporting the elderly. In addition, they substantiate further research on the mechanism of development of ideas about prosperous old age and their impact on behavioral strategies, as well as the creation of targeted programs that stimulate rational planning of old age. The revealed gaps between values and actual behavior require targeted measures aimed not only at promoting “correct” practices, but also at removing barriers that hinder their implementation for various socio-demographic groups. The paper contributes to understanding the mechanisms of old age building as a period of life when individual resources, cultural norms and institutional conditions intersect, determining the trajectories of well-being.