Ageing of the population

Автор: Medvedev G.O.

Журнал: Экономика и социум @ekonomika-socium

Статья в выпуске: 5-2 (24), 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

n several decades, aging of population has become an issue for the developed nations. While the process of population aging has been noticed in some European states in 19th century it had not become an issue until 1970s, when percentage of elders started to increase rapidly. States have to adapt new demographic reality. While discussing global population aging, it is important to understand the large demographic and social variability across regions and countries. In this paper, the process of population aging will be investigated on example of US and Japan.

Demography, population aging, japan, us

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140124615

IDR: 140124615

Текст научной статьи Ageing of the population

In pre-modern nations, the amount of children is generally high and child mortality rates are high as well; the amount of elders remains on a very low level. After beginning of demographic transition, states face a great and sudden fall in child mortality. Adapting to the new demographic reality takes several years (second stage of demographic transition), and the period, when birth rates were as high as before transition but mortality had already became low is when so-called “baby-boom’ is taking place. After, birth rate started to decline, but the amount of elders remained quite low. Support ratio (the number of people age 15-64 per one older person aged 65 or older) stays at a very high level, what provides a possibility to states to decrease social spends and use budget funds to support economic growth. This period is called “demographic dividend’ and usually longs up to 30 years. In these years, high temps of economic growth are observed. However, after the second demographic transition and increase in life expectancy the amount of people aged 65+ began to grow, while the amount of workers (age 16-64) remains constant or declines. States face a problem of growing social spendings with the decrease of budget receipts from taxes and slowing economic growth.

Japan, a pioneer in population aging, can be named a great source of experience for other countries. The US, however, can be named a state that succeed in performing several problems (governmental and nongovernmental as well), and, moreover, it is one of the best performing developed countries in the matter of population aging.

Main Theory

Demographical character of population is determined by the share of each age cohort. Countries with a very young age structure are those in which two-thirds or more of the population are younger than age 30 (typically, pre-modern countries that did not started demographical transition). Youthful age structure countries have more than 60 percent of their population younger than age 30, transitional age structure countries have between 45 and 60 percent of the population in under-30 age cohort. In countries with a mature age structure less than 45 percent of the country’s population is under age 30, while up to one-quarter of the population comprises older adults above age 60 [6, p. 1].

Aging of population is connected with three major factors. The first one and the most important is declining in fertility (TRF is considered almost equal or lower than replacement rate). The second is declining in mortality and growth in life expectancy, however its effect is limited in comparison with the previous factor. The third is migration (usually, significantly does not affect population aging countries) [11, pp. 12-13].

The main aspect in population aging is a fast increase in the share of elderly (people aged 65 or more): from 7.8% in 2008 to 14.7% in 2040 [9, p. S5]. While several European states did not faced such a rapid increase after the third state of demographic transition, the aging of the baby boom generation will become an issue for them as well. The next aspect is connected with growing importance of so-called ‘aging of elders’. The share of the older population at ages 80 and older (often referred to as the oldest-old) is growing more rapidly than the older population itself—worldwide, the growth rates for 1999–2000 were 3.5% for those aged 80 and older compared with 2.3% for those aged 65 and older [9, p. S7].

Economic progress is usually associated with high amount of labour force in population, while shares of children (under 16) and elders (over 65) remain low. This period that takes place after the second stage of demographic transition is called demographic dividend. The evidence is that population dynamics can explain between 1.37 and 1.87 percentage points of growth in GDP per capita in East Asia or as much as one-third of the miracle. Here, two main reasons can be named. The first one is connected with growing working age population that is the primal source of ‘producers’ and ‘consumers’ in society. The second reason is behavioristic [3, p.441]. However, while these cohorts that made an incredible economic growth possible become retired, so-called ‘demographic burden’ occurs, particularly with regard to increase in health and retirement spendings on the one hand and decrease in labour market supply.

While addressing challenges of supporting an aging population, state may provide a concept of positive aging. This concept includes the idea of Adulthood 2.0 (includes people aged from 55 to 75). Due to modern health treatment system and their lifestyle, after getting retired these people remain active and state should not understand them as ‘bruden’: if these resources are not used it is simply a waste of well-educated, skilled and experienced human capital. Society may benefit from people working longer years and the contribution they can provide as volunteers and their economic power as consumers and product makers. In order to reach that, Volunteer programmes, entrepreneurship schemes, ‘bridge jobs’ and life-planning (after the person’s 40s) should be developed [10, pp. 26-28]. Moreover, several researches considered that innovation is not primary connected with youths. Advanced technologies require more years of training in order to become familiar with existing ones, and, respectively, more years for developing new technologies based on previous knowledge. Between two types of intelligence (fluid and crystallized) only the first one declines after person’s 40s. However, crystallized intelligence declines much slower or even has tendency to increase [1, p. 301].

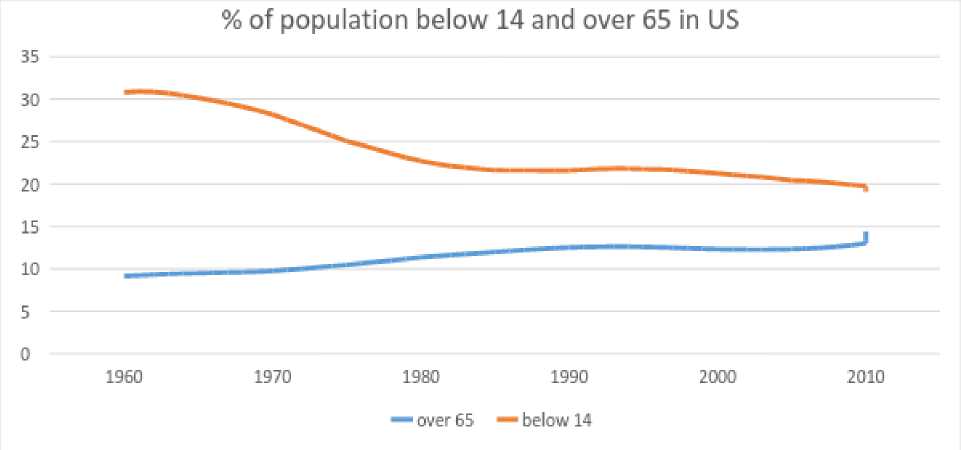

The US Demographic Overview

The population of the United States had been relatively “young” in the first half of the 20th century. In these years, country moved from first through second to third stage of demographic transition: from high fertility and mortality rates to low ones, with several years of high fertility and low mortality (‘baby-boom’ cohorts). While in the year 1900 the average life expectancy in the US equaled to 47 years and only 4.1% of all population was over 65, in 1960, the amount of senior citizens rose to 9.1% and the life expectancy was 69 on average. Nowadays, life expectancy has risen by astounding 29 years since the beginning of the century and is now 79 years on average. So, after living to 65 (usual retirement age), one can live on for about 17 more years without working and with receiving the social goods. And the percentage of population aged 65 and above was 14.4% in 2014 – it has been rising steadily since 1960s.

If to plot the data on the graph it can be noticed that the percentage of children has been falling while the percentage of elderly has been rising simultaneously. It can be seen that the population is ageing and that while in 1960s there were over 3 children per 1 senior, in 2014 the amount of them was almost equal.

The evidence is that aging is becoming faster while the baby boomer cohort enters old age: by 2030 20% of population will be older than 65. After biggest cohorts get retired, aging will get slower (22% by 2060) [11, p. 15]. However, now the US faces the challenge of adapting its social institutes (especially healthcare and retirement system) to new demographic reality in order to protect the most vulnerable in the population. One option that is likely to be considered involves relying on individual private savings and wealth accumulation. However, it is unlikely that individuals could save enough to maintain their pre-retirement welfare. The other option is connected with increase of the state’s role in supporting pension system, but, there, individuals can rely fully on the state support and the burden may be unaffordable.

Although population aging may or may not result in increasing proportions of older persons in poor health, the numbers experiencing that condition are almost certain to rise. However, according to the report issued by the Institute of Medicine in 2008, the U.S. healthcare workforce will be not ready to meet the health needs of a growing aging population [11, p.16]. However, here, the increase in elderly population will provide not only additional costs but benefits as well. For instance, health care spending in the US represents a large and increasing share of GDP, rising from 5.2% in 1960 to 16.0% in 2008 [11, p. 16]. Moreover, the US elderly cannot be considered as inactive, unproductive and fully depended. This negative stereotype is not supported by empirical evidence. Along with growing labor force participation among those older than age 65, high levels of volunteer work are shown [11, p. 16].

In the US, several programs were already successfully implemented. For instance, Village Model( is a program for elders who want to remain in their own homes. After paying a membership fee person gets access to network that provides a wide range of different service, from healthcare and education courses to delivery and home repairs. Village Model is driven by paid staff and volunteers as well. Some other features can be also mentioned, through them: technologies (boomers who are now retiring are much more familiar with new devices than previous generations) [10, pp. 27-28].

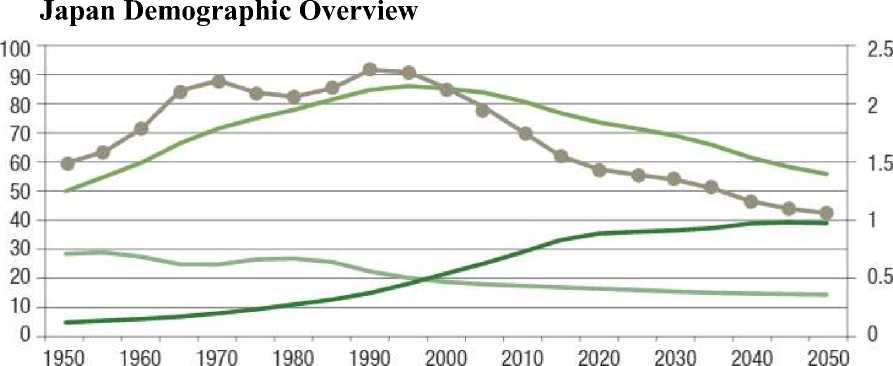

— 0-14 — 15-64 -- 65+ ^IDR(RH)

Note: estimates start from 2015

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015).

Wodd Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, DVD Edition

As well as in The US, in the first half of the 20 century Japan was moving from the first to third stage of the demographic transition. From the middle of 20 century, the share of the youngest cohort (under 14) began to decline, while share of elderly started to increase, from 5% in 1950 to more than 38% in 2015. The baby boom generation born in postwar years started retiring in 2007, and the old-age population will continue to increase disproportionately in coming years. TRF remains in a very low level (1.4), that is one-third lower than the replacement rate (2.1, as was previously said). According to that, share of elders in Japanese population will continue to increase disproportionately. Japan has recently become the first country in history with an average age of 40, as well as it is experiencing the most rapid aging of its older population. By 2040, 38% of the population aged 65 or older will be aged 80 or older, up from 22% in 2000.

The baby-boom generation should be described separately. This generation have had significant impact on the dynamism of Japanese society, determining Japaneese incredible economic growth (so-called ‘miracle’) [5, p. 33. 3, p. 441]. An economic boom associated with postwar reconstruction and the Korean War followed, along with a brief surge in fertility paralleling the Western baby boom. A ten-year plan to double the national income, implemented in 1960, achieved its target in six years. During this time, the TFR steadily declined while life expectancy and the median age of the population steadily increased [2, p. 103]. Due to the constant growth of the seniors share, the necessity of reforms has occurred. The age of eligibility for kosei nenkin, one of the two public pension schemes, has been raised from 55 to 65. Due to deflation pensions were overpaid since 2005. Politicians have been very reluctant to vote to reduce nominal pension payments—an unpopular move, especially among older voters [2, 105]. So, burden for working people remains quite high and, due to Japanese traditions of supporting elders on the one hand, and political difficulties (older generation forms large voicing bloc, and reforms against it will make politicians simply unpopular).

Social security spending in Japan (mostly pension, medical, and old-aged care spending) takes up nearly 55 percent of the total non-interest spending by the general government [5, p. 52]. Cuts in the replacement ratio would undermine the pension’s role in alleviating old-age poverty, while higher contributions would discourage labor market participation and aggravate already large intergenerational imbalances.

In order to decrease the burden for working population, Japanese elderly should encouraged to participate workforce as well as in the US. This is the main measure that could be undertaken in conditions of constant and disproportional growth of elderly share. For instance, several changes can be made in Japanese companies’ HRM policy, providing new approaches of ‘psychological contracts’ (individual beliefs, shaped by organization, regarding terms of an exchange agreement) between employers and their older employees [4, p. 106].

Conclusion

In this paper the general approaches of population aging were overlooked, with primal examples of the US and Japan. Population aging started in the middle of the 20 century when most developed countries went through the third stage of demographic transition. The decrease in child dependency ratio (with elderly dependency ratio remained low) provided a ‘demographic dividend’: a possibility for rapid economic growth, however, causing increased economic burden on working population after 20-30 years. While there is no viable demographic way to avoid population aging, there are some measures could be undertaken to avoid social crisis that can occur. Firstly, the level of seniors participation in the workforce should be increased, by creating ‘bridge jobs’, popularisation volunteer programs through elderly, life-planning strategies, as well as through changing employers’ HRM policy. Other measures are connected with providing more positive image of old aged people.

Список литературы Ageing of the population

- Ang J, Madsen J. Imitation Versus Innovation in an Aging Society: International Evidence Since 1870. /J. Ang, J. Madsen. -Journal Of Population Economics. April 2015;28(2). P. 299-327. Режим доступа: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 23.04.2016.

- Aoki R. A Demographic Perspective on Japan's 'Lost Decades'. /R. Aoki. -Population And Development Review. 2012;38. P. 103-112.Режим доступа:: EconLit, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 23.04.2016.

- Bloom, D.E., Williamson, J.G. Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia. World Bank Economic Review. 1998. -P. 419-455.

- Keith J. Comparing HRM Responses to Ageing Societies in Germany and Japan: Towards a Aew Research Agenda. /J. Keith. -Management Revue. March 2016;27(1/2). P. 97-113.Режим доступа: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 23.04.2016.

- Kobayashi M. Housing and Demographics: Experiences in Japan. /M. Kobayashi. -Housing Finance International. Winter 2015;(12). P. 32-38. Режим доступа: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 23.04.2016.

- Madsen, E. L. The Effects of Age Structure on Development. Policy and Issue Brief /E. L. Madsen, B. Daumerie, K. Hardee. -Washington: Population Action International, 2010. -Р. 1-4. -Режим доступа: http://populationaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/SOTC_PIB.pdf. -Дата доступа: 30.04.2016.

- Nobuo S. Ageing Society and Evolving Wage Systems in Japan. /S. Nobuo. -Management Revue. March 2016;27(1/2). -P. 50-62. Режим доступа: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 30.04.2016.

- Oliver M. Population Ageing and Economic Growth in Japan. /M. Oliver. -International Journal Of Sociology & Social Policy. November 2015;35(11/12). P. 841. Режим доступа: Publisher Provided Full Text Searching File, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 23.04.2016.

- Schoeni R., Ofstedal M. Key Themes in Research on the Demography of Aging /R. Schoeni, M. Ofstedal. -Demography, August 2, 2010. -P. S5-S15. Режим доступа: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. -Дата доступа: 30.04.2016.

- Timmermann S. Big Ideas and Trends from the Aging Field: Connecting the Dots with Financial Services /S. Timmermann. -Journal Of Financial Service Professionals. September 2014. -P. 26-30. Режим доступа: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 30.04.2016.

- Uhlenberg P. Demography Is Not Destiny: The Challenges and Opportunities of Global Population Aging. /P. Uhlenberg. -Generations. Spring 2013;37(1). -P. 12-18. Режим доступа: SocINDEX with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Дата доступа: 30.04.2016.