Archaeology of the Slavic period in northern Germany

Автор: Bleile R.

Журнал: Краткие сообщения Института археологии @ksia-iaran

Рубрика: Материалы конференции «Век археологии: открытия - задачи - перспективы» (10-11 апреля 2019 г., ГИМ)

Статья в выпуске: 259, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In the north-eastern part of Germany, between the Rivers Elbe and Oder, Slavic societies settled from the 7th to the 12th century AD. The last decades of archaeological research on Slavic sites of this period shed light on different features and brought outstanding finds to light. More than 600 Slavic fortresses are known in the eastern part of Germany. Only a few have been excavated so far. Close to the coast of the Baltic Sea, maritime trading centres developed under Scandinavian influences. The article gives an overview of results of archaeological fieldwork. In the second part, the focus is on the important and well-known fortress Starigard/Oldenburg, situated in Schleswig-Holstein. The chronicler Adam of Bremen wrote that one had to board a ship there if one wanted to travel by sea to Wollin in the Oder estuary. Starigard was the seat of the ruling princes of the Wagri and the site of the first bishopric in the area of the Obodrites. The location of the fortress and Adam of Bremen’s information were factors in spotting a maritime trading centre in Starigard/Oldenburg as well. In the eastern area of the rampart, a princely court was excavated. Three phases of a hall could be identified. Phases four and five were interpreted as churches because a lot of graves are situated inside and along the southern wall. Church and cemetery were destroyed in a fire disaster, which could be associated with the Slav uprising of 983 AD and with which the first bishopric phase ended. At about this point inside the church, where the altar once stood, there was a 2-m stone plinth containing a posthole. A figure of a god was presumably set in it. Finds proved the practice of both Christian and pagan religious activities. Others are examples of the function of Starigard as an important hub in a maritime trading network. New research is planned for the future.

Early middle ages, west slavs, northern germany, mecklenburg-western pomerania, schleswig-holstein, ramparts, christianisation, starigard/oldenburg

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143173109

IDR: 143173109

Текст научной статьи Archaeology of the Slavic period in northern Germany

For many years, the archaeology of the Slavic period (7th to 12th centuries AD) in the north-eastern part of Germany has worked with an interdisciplinary approach involving place name research, history and natural sciences ( Brather , 2008. S. 9–29; Müller, Wehner , 2016)1. Emphasis has been and remains on the identification of Slavic cultural relics as well as the description of cultural contacts, accumulations and transformations. This is so important because cultural contacts could have existed between Slavic settler groups migrating in the 7th century and a remaining Germanic population and because there was already contact between the Slavs and the Frankish and later the Ottonian Empire as well as the Danish and Swedish elites from the 8th century ( Biermann , 2016a; Lübke , 2001; Müller-Wille , 2003). Moreover, the Slavic culture in this region from the second half of the 12th century unfolded in the course of the reformation of German law in the medieval German culture ( Lübke , 2014; Die bäuerliche Ostsiedlung…, 2005). In the far north-west, the Slavs were also in the close vicinity of Saxons, Danes and Frisians. The area of today’s Schleswig-Holstein is therefore also described as the hub for those peoples ( Müller-Wille , 2002).

The questions of what exactly Slavic cultural expression actually is, how this was influenced and what elements of other cultures reached the area play a special role (generally: Brather , 2004, especially pp. 236–239). Germania Slavica research, a term from the mid 20th century, which was organised by, among others, the Leipzig Centre for the History and Culture of East Central Europe, consequently enjoys a high standing (Struktur und Wandel…, 1998; Schich , 2003; Brather, Kratzke , 2005).

In the view of archaeology, the term «Slavs» is a scientific construct, of linguistic, archaeological and ethnic components. Historical linguistics, history and archaeology each developed their own methods from various sources and formed their specific concepts. Consequently, what can be understood under «Slavs» in the region at a particular time depends on the scientific viewpoint. Archaeology uses the term archae-ologically or historically for societies of the Early and High Middle Ages without postulating ethnic or political units with it ( Brather , 2008. S. 44–50). The term «West Slavs» is to be understood as the geographical limit to the areas of today’s Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, parts of Austria and eastern parts of Germany (Ibid. S. 2, 3. Fig. 1). Moreover, there is a term «Elbe Slavs», which is supposed to cover geographically the tribes and tribal unions between Elbe and Oder, Baltic Sea and the Erz Mountains ( Lübke , 1993. S. 21; 2001. S. 23, n. 1). The tribal unions of the Obodrites in the west and the Veleti, later called the Lutici, in the east settled in the very north of this Elbe Slavic area. Several subtribes belonged to them at the time ( Biermann , 2014. S. 157).

Main topics of the archaeology of the West Slavs

The migration of the first Slavic societies and their development are an important field of research ( Biermann , 2016a; 2016b). Here, two questions in particular are interesting: when exactly did the first Slavic settlers immigrate and did they encounter the rest of the Germanic populations or not? In the answering of these questions, dendrochronological datings of rampart constructions, wells, boardwalks, and bridges became just as important as palynological studies on the basis of core samples from lakes. The reforestation in the Migration Period can be readily recognised, for example in the core sample from the Belauer See in Schleswig-Holstein ( Wiethold , 1998. S. 154–158). It can be seen from the dendrochronological datings that the first Slavic settlers migrated to the region in the second half of the 7th century at the earliest ( Dulinicz , 2006. S. 39–51). Onomastics provided the indication that Indo-Germanic names of water bodies survived into the Slavic period ( Udolph , 2016).

Settlement archaeology and research into cultural landscapes form a further focus of research. Several studies during the past two decades have investigated the small-and large-scale settlement landscapes, such as the location of unfortified Slavic settlements ( Klammt , 2015) and the development of the settlement clusters «Werder» in Mecklenburg ( Schneeweiß , 2003). Various data like soil quality maps, reliefs, changes in water bodies, and qualities of find sites were able to be linked through the deployment of geographic information systems.

In the districts of Schwerin, Rostock and Neubrandenburg of the former German Democratic Republic, which today are parts of the federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the archaeology of the Slavic period was primarily centrally structured through the Academy of Sciences of the German Democratic Republic ( Brather , 2008. S. 24, 25). Emphasis was placed on excavations in a few of the several hundred Slavic forts ( Struve , 1981; Biermann , 2016b), on burial grounds ( Paddenberg , 2000; Pollex , 2010) and on the maritime trading centres on the coast that showed Scandinavian influences ( Kleingärtner , 2014). The fortresses of Behren-Lübchin ( Schuldt , 1965), Teterow ( Unverzagt, Schuldt , 1963) and Groß Raden ( Schuldt , 1985) as well as the maritime trading centres Ralswiek ( Herrmann , 1997–2008) and Menzlin ( Schoknecht , 1977) rank among the most important excavations.

But district museums also undertook excavations, for example the museum in Schwerin on the lowland fort and trading centre of Parchim-Löddigsee. The excavations were continued by the Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania State Office for the Preservation of Monuments ( Paddenberg , 2012). This State Office also continued important excavations at the maritime trading centre of Groß Strömkendorf ( Jöns et al. , 1997).

In Schleswig-Holstein in the old Federal Republic, the Collaborative Research Centre 17 of the German Research Foundation, which was based at Kiel University from 1973 to 1983 (Gabriel, 1984. S. 7, 13, 14; Starigard/Oldenburg…, 1991. S. 7), is worth mentioning. Later, the interdisciplinary research project «Starigard/ Oldenburg – Wolin – Novgorod: Besiedlung und Siedlungen im Umland slawischer Herrschaftszentren» was developed (Müller-Wille, 1998) A research project into the Slavs on the middle Lower Elbe, integrating excavations at fortresses and settlements, was undertaken through collaboration among institutions from the federal states of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Lower Saxony and Brandenburg between 2005 and 2010 (Slawen an der Elbe…, 2011; Slawen an der unteren Mittelelbe…, 2013).

Highlights of archaeological features and finds

Numerous excavations and studies brought a lot of impressive results to light. At this point only a few can be named to underline the great potential of the region for research into the Slavic settlement period.

Indications of temples and idols were found in several fortresses. The temple site of Arkona at the northern tip of the island of Rügen is of special importance ( Ruchhöft , 2018). Moreover, however, the wooden idol from the island Fischerinsel in the Tollensesee ( Gringmuth-Dallmer, Hollnagel , 1971) and the find of a temple building from the outer bailey settlement of Groß Raden ( Schuldt , 1985) as well as the temple of Parchim-Löddigsee ( Keiling , 1984) are salient.

The region is rich in water bodies. In many lakes there are islands on which unfortified settlements or forts stood during the Slavic period. Numerous bridges to these islands have been proved though excavations in moist ground and through underwater archaeological investigations ( Herrmann , 1975; Bleile , 1999). The 750-m long bridge from Teterow ( Unverzagt, Schuldt , 1963) as well as a bridge in the Oberruckersee, which led across 20-m deep water ( Herrmann , 1966), ranks among the best known. On the Plauer See, the rise in the water level in the 11th century through climatic changes and in the 13th century through the construction of watermills were able to be proved through the chronological sequence of paths and bridges ( Bleile , 2008).

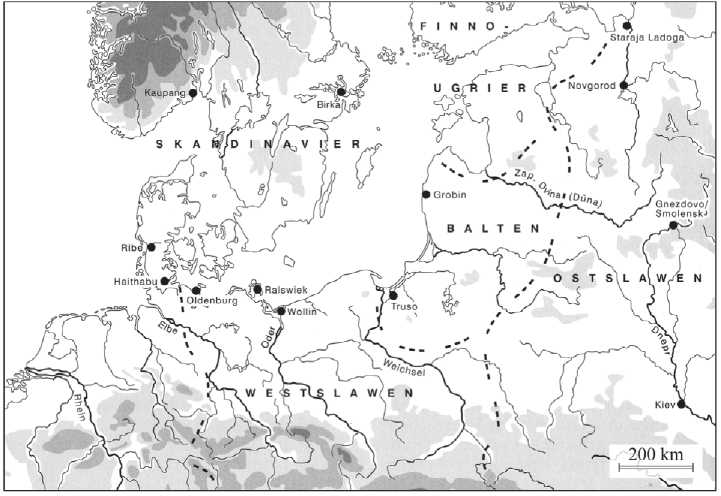

A special feature of the region is the maritime trading centres that had been founded by Scandinavian seafarers, at regular intervals like beads on a string, during the early Slavic period ( Kleingärtner , 2014). Their investigation provided extensive material that leads to the awareness of the integration of the region into a trading network encompassing the whole of Europe as well as the Middle East. The four boats from Ralswiek rank among the most important finds ( Herfert , 1968; Herrmann , 1997–2008. Part 2). Together with the wreck from Schuby-Stand, they show us the commonalities and differences in Slavic and Scandinavian shipbuilding ( Nakoinz , 1998). The maritime trading centres Groß Strömkendorf, Rostock-Dierkow, Ralswiek and Menzlin petered out in the mid Slavic period of the 10th century at the latest. The Wagri central fortress Starigard/Oldenburg alone, which is described as «civitas maritima» in the chronicles of Adam of Bremen in the 11th century (Fig. 1), survived up to the German legal system period (Starigard/Oldenburg…, 1991).

Special focus: the Slavic ramparts of Starigard/Oldenburg

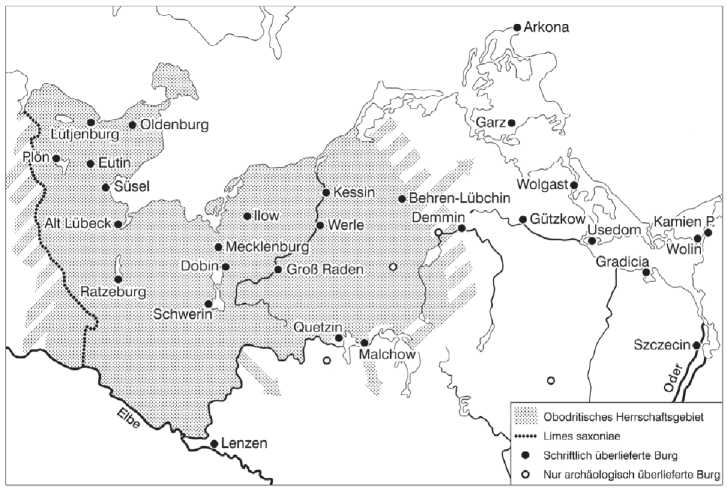

The ramparts of Starigard/Oldenburg are located in Schleswig-Holstein, on a promontory north of the Oldenburger Graben in the centre of the town of Oldenburg not far from the Baltic Sea coast (Fig. 2). When in use, the fortress was presumably bounded by water on two sides. The Oldenburger Graben, which today is a depression between

Fig. 1. Trading centres and ethnic groups of the 8th to 11thcenturies in the Baltic Sea Region (source: Muller-Wille , 2011. S. 268. Kt. 1)

Fig. 2. Slavic princely and territorial forts at the beginning of the 12th century in the area of Obodrite rule (source: Muller-Wille , 2003. S. 251. Fig. 10)

the Hohwacht Bay in the west and the Bay of Lübeck in the east, could have been navigable in the Early Middle Ages. In this case, the ramparts would lie at the junction of overland and water routes. The chronicler Adam of Bremen wrote that one had to board a ship if one wanted to travel by sea to Wollin on the Oder estuary. Starigard was the seat of the ruling princes of the Wagri and the site of the first bishopric in the area of the Obodrites ( Struve , 1989). The location of the fortress and Adam of Bremen’s information were factors in spotting a maritime trading centre in Starigard/Oldenburg as well.

The first excavations took place in the years 1953 to 1958 and provided knowledge of the great potential of this place. Consequently, Starigard/Oldenburg was able to be integrated into the Collaborative Research Centre 17 of the German Research Foundation. From 1973 to 1976 as well as from 1979 to 1986, excavations, in which scientists from the Ukraine also took part, were undertaken annually. The management of the research project was in the hands of the Director of the State Archaeological Museum, Professor Karl Wilhelm Struve, the direction of excavations with Dr Ingo Gabriel. The excavations included the multiple ring of fortifications as well as the internal buildings of the fortress. The aim was to investigate the chronological sequence of the fortress complex and particularly the internal buildings ( Struve , 1985).

The oval basic form with concave long sides characterises the ramparts. It is the result of extensions and modifications. Phases I and II belong to a hillfort of the 9th century, phases III and IV to the large fortress of the 9th to 12th centuries, and phase V indicates the multipart fortress of the 13th century ( Gabriel , 1984).

The first fortress was a hillfort with a diameter of 140 m. The position and size assign it to the typical early Slavic elevated fortresses of the Baltic Sea region. An open settlement was situated to the east of the hillfort. In the third phase, this settlement was integrated into the fortress through an extension of the ramparts, which now extended 260 m east to west. Consequently, Starigard became the Obodrites’ biggest fortress.

This enormous size alone illustrates its marked status as the central fortress of the Wagri princes. The construction of the ramparts scarcely differentiates itself from other known fortresses. In contrast, the finds of the internal buildings are much more interesting, because they are unique in the whole of the West Slavic area. In Starigard, a princely courtyard of the 9th and 10th centuries with the first wooden church buildings and a princely cemetery were uncovered ( Gabriel, Kempke , 2011).

Some important features of this rampart

This multiphase court complex consists of a palisade, a hall with courtyard as well as wing constructions and stores. The finds of the oldest, double-span hall of post construction with a central long fire are impressive. On the basis of corresponding finds of tools, a fine forging workshop within the area of this oldest courtyard is verifiable. The layout of the princely courtyard is comparable with Carolingian royal residences and could have been inspired by these (on the features of the courtyard and the churches, see: Gabriel , 1989b; Gabriel, Kempke , 2011).

A central long fire could not be verified in the second hall. This second princely courtyard dates to the second and last thirds of the 9th century. The centre of the 17-m long and 12-m wide princely hall forms an almost square room with only one central post. The side aisles in the east and west are each subdivided into four with posts.

There followed a third princely court, whose finds are worse preserved and which dates to the first third of the 10th century. This third post construction is a hall building with a length of 18 m and a width of 6.5 m without recognisable constructional subdivisions. External supports surround the building on the long sides. Remains of crucibles and metal as well as a chimney surrounded by stone attest also the work area of a fine forging workshop within the courtyard of this phase.

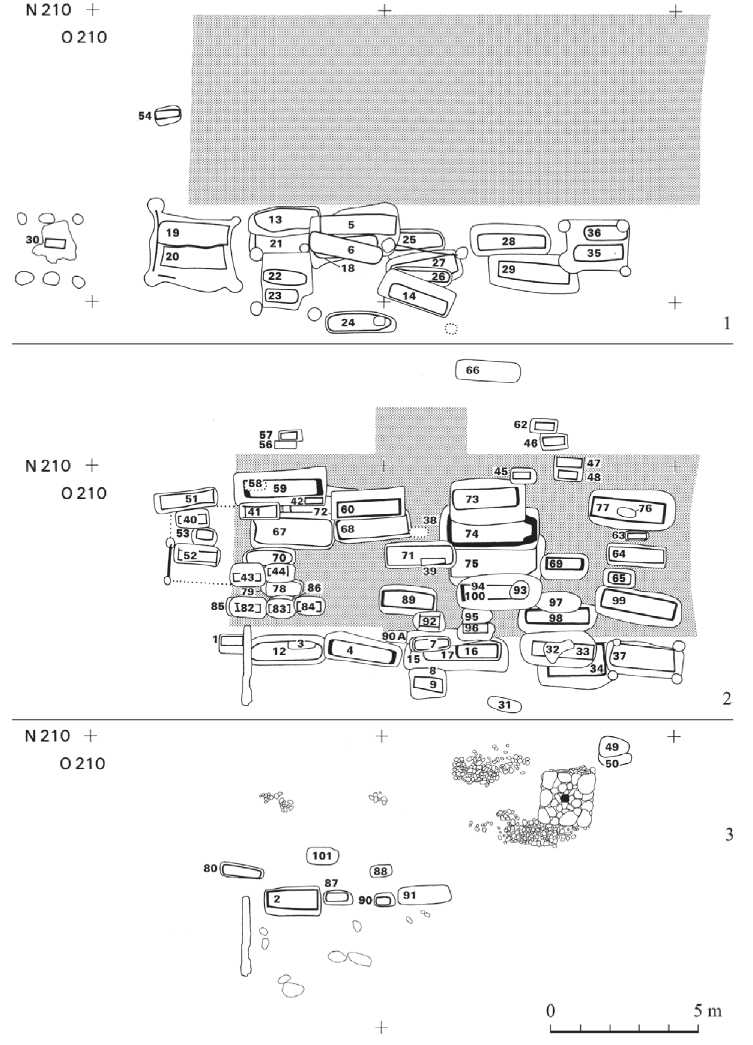

In about the middle of the 10th century, an 18-m long and 6.5-m wide post building was erected on the site of the third princely hall (Fig. 3). Burials took place in front of its southern wall with eaves. We know, through the grave goods from the subsequent phase, that they must have related to members of the princely elite. The burials directly next to the large building alter its interpretation. It is now to be regarded as a church, especially because graves were also constructed inside the building in the next phase.

The fifth and final hall construction was clearly a church. It is a 16-m long and 6-m wide post construction, which had been erected on clay foundations. Again, finds of an internal structure are absent, but then numerous graves lay in the interior of the church.

Since, without exception, inhumation burials in an east-west alignment are involved (on anthropological research, see: Teegen, Schultz , 2017) and these lie mostly in a building, a Christian burial practice is demonstrated. The individual burial grounds and numerous grave goods are additional evidence of social and, in some cases, probably the geographical origin of the buried as well.

Of special importance are the central graves 74 and 75, which are aligned in parallel in the middle of the church west of an open space – this is interpreted as the site of an altar. Its position already allows the assumption that the buried could be the founder or founders of their own church.

Both deceased were laid in huge tree coffins. In grave 74, there was a sword, a casket with gaming pieces, a complex of textile remains, which are regarded as the remains of a reliquary pouch, with threads of gold flattened wire and gold sheet rattles as well as a filigree gold bead. Grave 75 contained a bronze dish and the point of a lance. Such grave goods are not to be found in other graves in the cemetery. They underline the high rank of the buried persons. They would be regarded as marshal and seneschal in the neighbouring German empire ( Gabriel , 2006. S. 151).

Church and cemetery were destroyed in a fire disaster, which could be associated with the Slav uprising of 983 and with which the first bishopric phase ended.

Graves were also laid at the same place after the destruction of the church. The grave goods of precious metal or riding spurs attribute them again to the elite. Another fire disaster followed, which is dated to around 1000 and can possibly be associated with the more recent insurgency of the year 1018. At about this point, where the altar once stood, there was a 2-m stone plinth containing a posthole. A figure of a god was presumably set in it. Horse skulls and horse limbs had been ritually deposited in the surrounding area as remains of cult-motivated meals ( Gabriel, Kempke , 2011. S. 17).

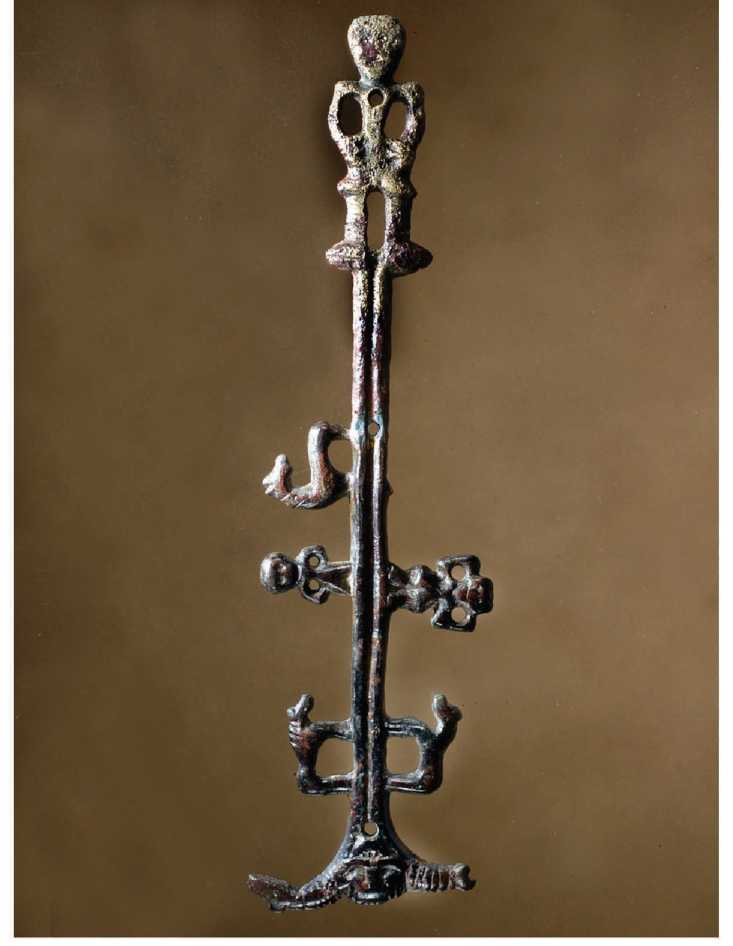

These finds illustrate the spatial and temporal closeness of paganism and Christianity in Starigard. The expression of this is, moreover, in finds such as a small pectoral cross from a child’s grave, remains of a church bell and fragments of two

Fig. 3. Starigard/Oldenburg. The northern cemetery inside the princely court

1 – central building number 4 (church) with graves in front of the southern wall; 2 – central building number 5 (church) with graves inside and in front of the southern as well as the eastern wall; 3 – stone plinth with posthole at the position of the formal altar, ritual deposits of horse bones, graves, 10th century (source: Gabriel, Kempke , 2011. S. 16. Fig. 6)

reliquary caskets on the one hand as well as the knife sheath fitting with cosmological iconographic programme (Fig. 4), the wooden pocket idol and the small clay doll on the other ( Gläser et al. , 2002 S. 38–41, 99, 117, 119–128, 133–136).

Fig. 4. Starigard/Oldenburg. Cast bronze fittings with cosmological imagery, 10th century. Archaeological Museum Gottorf Castle

Everyday utensils, weapons, dress accessories, and jewellery from various European regions rank among the extensive find material ( Gabriel , 1989a). The integration of the place into a maritime trading network is illustrated by the exceptionally high number of bones of raptors, which had presumably been used for falconry. In the whole of the Baltic Sea region, only Starigard and the maritime trading centres Groß Strömkendorf, Haithabu and Schleswig exhibit a significant accumulation of finds of this kind. Consequently, the hunting birds seem to have been commodities that were transported over the Baltic Sea presumably from Scandinavia to Starigard ( Bleile , 2018. P. 1317–1321). This finding is further evidence that either Starigard itself was a maritime trading centre or such a centre existed in its immediate surroundings on the Oldenburger Graben.

A look into the future

Despite this knowledge that was able to be gained from the excavation trench on the east of the ramparts, the extensive find material and the documentation of finds holds still more potential. This means that the excavation trenches on the west of the ramparts have not been evaluated yet. In addition, investigations of the skeleton material of the princely cemetery are being strived for. Indeed, anthropological and pathological studies have already yielded interesting indications of age at death and diseases, but there remain questions about family relationships, the origins of people and their diet. There are therefore plans to commission a new research project for this important central Slavic fortress2.

Список литературы Archaeology of the Slavic period in northern Germany

- Biermann F., 2014. Zentralisierungsprozesse bei den nördlichen Elbslawan // Zentralisierungsprozesse und Herrschaftsbildung im frühmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa / Hrsg. P. Sikora. Bonn: Habelt-Verlag. S. 157-194. (Studien zur Archäologie Europas; 23.)

- Biermann F., 2016a. Über das "dunkle Jahrhundert" in der späten Völkerwanderungs- und frühen Slawenzeit im nordostdeutschen Raum // Die frühen Slawen - von der Expansion zu gentes und nationes. Beiträge der Sektion zur slawischen Frühgeschichte des 8. Deutschen Archäologiekongresses in Berlin, 6.-10. Oktober 2014 / Hrsg.: F. Biermann, T. Kersting, A. Klammt. Langenweissbach: Beier & Beran. S. 9-26. (Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte Mitteleuropas; 81/1.)

- Biermann F., 2016b. North-Western Slavic Strongholds of the 8th-10th Centuries AD // Fortified Settlements in early Medieval Europe. Defended Communities of the 8th-10th Centuries / Eds.: Chr. Neil, H. Hajnalka. Oxford; Philadelphia: Oxbow Books. P. 85-94.

- Bleile R., 1999. Slawische Brücken in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern // Bodendenkmalpflege in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Jahrbuch. 46 (1998). Lübstorf: Landesamt für Bodendenkmalpflege Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. S. 127-169.

- Bleile R., 2008. Quetzin - Eine spätslawische Burg auf der Kohlinsel im Plauer See. Befunde und Funde zur Problematik slawischer Inselnutzungen in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Schwerin: Landesamt für Kultur und Denkmalpflege. 216 S.

- Bleile R., 2018. Falconry among the Slavs of the Elbe? // Raptor and human - falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale. Vol. 3 / Eds.: K.-H. Gersmann, O. Grimm. Kiel; Hamburg: Wachholtz Murmann Publishers. P. 1303-1370.

- Brather S., 2004. Ethnische Interpretationen in der frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie. Geschichte, Grundlagen und Alternativen. Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter. 807 S. (Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde; 42.)

- Brather S., 2008. Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. 2. überarbeitete Auflage. Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter. 449 S.

- Brather S., Kratzke Chr., 2005. Auf dem Weg zum Germania Slavica-Konzept. Perspektiven von Geschichtswissenschaft, Archäologie, Onomastik und Kunstgeschichte seit dem 19. Jahrhundert Leipzig: Leipziger Universitäts-Verlag. 210 S. (GWZO-Arbeitshilfen; 3.)

- Die bäuerliche Ostsiedlung des Mittelalters in Nordostdeutschland. Untersuchungen zum Landesausbau des 12. bis 14. Jahrhunderts im ländlichen Raum / Hrsg.: F. Biermann, G. Mangelsdorf. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2005. 400 S. (Greifswalder Mitteilungen; 7.)

- Dulinicz M., 2006. Frühe Slawen im Gebiet zwischen unterer Weichsel und Elbe. Eine archäologische Studie. Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag. 423 S.

- Gabriel I., 1984. Starigard/Oldenburg. Hauptburg der Slawen in Wagrien. I: Stratigraphie und Chronologie (Ausgrabungen 1973-1982). Neumünster: Karl Wachholtz Verlag. 215 S.

- Gabriel I., 1989a. Hof- und Sakralkultur sowie Gebrauchs- und Handelsgut im Spiegel der Kleinfunde von Starigard/Oldenburg // Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission. 69 (1988). Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. S. 103-291.

- Gabriel I., 1989b. Zur Innenbebauung von Starigard/Oldenburg // Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission. 69 (1988). Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. S. 55-86.

- Gabriel I., 2006. Der König von Wagrien und sein goldener Reliquienbeutel // Magischer Glanz. Gold aus archäologischen Sammlungen Norddeutschlands / Hrsg.: R. Bleile. Schleswig: Archäologisches Landesmuseum. S. 144-155.

- Gabriel I., Kempke T., 2011. Starigard/Oldenburg. Hauptburg der Slawen in Wagrien. VI: Die Grabfunde. Einführung und archäologisches Material. Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag. 256 S.

- Gläser M., Hahn H.-J., Weibezahn I., 2002. Heiden und Christen - Slawenmission im Mittelalter. Lübeck: Schmidt-Röhmhild. 151 S.

- Gringmuth-Dallmer E., Hollnagel A., 1971. Jungslawische Siedlung mit Kultfiguren auf der Fischerinsel bei Neubrandenburg // Zeitschrift für Archäologie. 5. S. 102-133.

- Herfert P., 1968. Frühmittelalterliche Bootsfunde in Ralswiek, Kr. Rügen (Zweiter Grabungsbericht) // Ausgrabungen und Funde. 13, 4. S. 211-222.

- Herrmann J., 1966. Die slawischen Brücken aus dem 12. Jahrhundert im Ober-Ückersee bei Prenzlau. Ergebnisse der archäologischen Unterwasserforschungen // Ausgrabungen und Funde. 11, 4. S. 215-230.

- Herrmann J., 1975. Underwater archaeological research in the German Democratic Republic // International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 4, 1. P. 138-141.

- Herrmann J., 1997-2008. Ralswiek auf Rügen. Die slawisch-wikingischen Siedlungen und deren Hinterland. Bd. 1-5. Schwerin: Landesamt für Kultur und Denkmalpflege Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. 5 Bd.

- Jöns H., Lüth F., Müller-Wille M., 1997. Ausgrabungen auf dem frühgeschichtlichen Seehandelsplatz von Groß Strömkendorf, Kr. Nordwestmecklenburg. Erste Ergebnisse eines Forschungsprojektes // Germania. 75, 1. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. S. 193-221.

- Keiling H., 1984. Ein jungslawisches Bauwerk aus Spaltbohlen von Parchim // Ausgrabungen und Funde. 29, 3. S. 135-144.

- Klammt A., 2015. Die Standorte unbefestigter Siedlungen der nördlichen Elbslawen. Zwischen Klimaveränderung und politischem Wandel. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt. 294 S. (Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie; 277.)

- Kleingärtner S., 2014. Die frühe Phase der Urbanisierung an der südlichen Ostseeküste im ersten nachchristlichen Jahrtausend. Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag. 503 S. (Studien zur Siedlungsgeschichte und Archäologie der Ostseegebiete; 13.)

- Lübke Chr., 1993. Slaven zwischen Elbe/Saale und Oder: Wenden - Polaben - Elbslaven? // Jahrbuch für die Geschichte Mittel- und Ostdeutschlands. 41. München; New Providence; London; Paris: Saur. S. 17-43.

- Lübke Chr., 2001. Die Beziehungen zwischen Elb- und Ostseeslawen und Dänen vom 9. bis zum 12. Jahrhundert: Eine andere Option elbslawischer Geschichte? // Zwischen Rerik und Bornhöved. Die Beziehungen zwischen den Dänen und ihren slawischen Nachbarn vom 9. bis ins 13. Jahrhundert / Hrsg.: O. Harck, Chr. Lübke. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. S. 23-36.

- Lübke Chr., 2014. Von der Sclavinia zur Germania Slavica: Akkulturation und Transformation // Akkulturation im Mittelalter / Hrsg R. Härtel. Ostfildern: Jan Thorbecke Verlag. S. 207-233. (Vorträge und Forschungen; LXXVIII.)

- Müller U., Wehner D., 2016. Wagrien im Brennpunkt der Slawenforschung // Mehrsprachige Sprachlandschaften. Das Problem der slavisch-deutschen Mischtoponyme. Akten der Kieler Tagung 16.-18. Oktober 2014 / Hrsg.: K. Marterior, N. Nübler. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag. S. 209-260.

- Müller-Wille M., 1998. Starigard/Oldenburg - Wolin - Novgorod: Besiedlung und Siedlungen im Umland slawischer Herrschaftszentren. Ein fachübergreifendes Forschungsprojekt // Struktur und Wandel im Früh- und Hochmittelalter. Eine Bestandsaufnahme aktueller Forschungen zur Germania Slavica / Hrsg. Chr. Lübke. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. S. 187-198. (Forschungen zur Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Mitteleuropa; 5.)

- Müller-Wille M., 2002. Schleswig-Holstein. Drehscheibe zwischen Völkern // Spuren der Jahrtausende. Archäologie und Geschichte in Deutschland / Hrsg.: U. von Freeden, S. von Schnurbein. Stuttgart: Theiss. S. 368-387.

- Müller-Wille M., 2003. Zwischen Kieler Förde und Wismarbucht. Archäologie der Obodriten vom späten 7. bis zur Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts // Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission, 83 (2002). Mainz: Philip von Zabern. S. 243-264.

- Müller-Wille M., 2011. Die Ostseegebiete während des frühen Mittelalters. Kulturkontakt, Handel und Urbanisierung aus archäologischer Sicht // Zwischen Starigard/Oldenburg und Novgorod. Beiträge zur Archäologie west- und ostslawischer Gebiete im frühen Mittelalter / Hrsg. M. Müller-Wille. Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag. S. 267-293. (Studien zur Siedlungsgeschichte und Archäologie der Ostseegebiete; 10.)

- Nakoinz O., 1998. Das mittelalterliche Wrack von Schuby-Strand und die Schiffbautraditionen der südlichen Ostseeküste // Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt. 28. Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums. S. 311-322.

- Paddenberg D., 2000. Studien zu frühslawischen Bestattungssitten in Nordostdeutschland // Offa. Berichte und Mitteilungen zur Urgeschichte, Frühgeschichte und Mittelalterarchäologie. 57. Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag. S. 231-345.

- Paddenberg D., 2012. Die Funde der jungslawischen Feuchtbodensiedlung von Parchim-Löddigsee, Kr. Parchim, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag. 390 S. (Frühmittelalterliche Archäologie zwischen Ostsee und Mittelmeer; 3.)

- Pollex A., 2010. Glaubensvorstellungen im Wandel. Eine archäologische Analyse der Körpergräber des 10. bis 13. Jahrhunderts im nordwestslawischen Raum. Rahden/Westfalen: Verlag Marie Leidorf. 681 S. (Berliner Archäologische Forschungen; 6.)

- Ruchhöft F., 2018. Arkona - Glaube, Macht und Krieg im Ostseeraum. Schwerin: Landesamt für Kultur und Denkmalpflege Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. 334 S.

- Schich W., 2003. Germania Slavica. Die ehemalige interdisziplinäre Arbeitsgruppe am Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut der Freien Universität Berlin // Jahrbuch für die Geschichte Mittel- und Ostdeutschlands, 48 (2002). München: K. G. Saur. S. 269-297.

- Schneeweiß J., 2003. Der Werder zwischen Altentreptow-Friedland-Neubrandenburg vom 6. Jh. vor bis zum 13. Jh. n. Chr. Siedlungsarchäologische Untersuchung einer Kleinlandschaft in Nordostdeutschland. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt. 239 S. (Universitätsforschungen zur Prähistorischen Archäologie; 102.)

- Schoknecht U., 1977. Menzlin - Ein frühgeschichtlicher Handelsplatz an der Peene. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften. 215 S.

- Schuldt E., 1965. Behren-Lübchin. Eine spätslawische Burganlage in Mecklenburg. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. 157 S.

- Schuldt E., 1985. Groß Raden. Ein slawischer Tempelort des 9./10. Jahrhunderts in Mecklenburg. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. 234 S.

- Slawen an der Elbe / Hrsg.: K.-H. Willroth, J. Schneeweiß. Göttingen: Wachholtz, 2011. 246 S. (Göttinger Forschungen zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte; 1.)

- Slawen an der unteren Mittelelbe. Untersuchungen zur ländlichen Besiedlung, zum Burgenbau, zu Besiedlungsstrukturen und zum Landschaftswandel. Beiträge zum Kolloquium vom 7. bis 9. April 2010 in Frankfurt a. Mein / Hrsg.: K.-H. Willroth, H.-J. Beug, F. Lüth, F. Schopper, S. Messal, J. Schneeweiß. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2013. 305 S. (Frühmittelalterliche Archäologie zwischen Ostsee und Mittelmeer; 4.)

- Starigard/Oldenburg. Ein slawischer Herrschersitz des frühen Mittelalters in Ostholstein / Hrsg. M. Müller-Wille. Neumünster: Karl Wachholtz Verlag, 1991. 328 S.

- Struktur und Wandel im Früh- und Hochmittelalter. Eine Bestandsaufnahme aktueller Forschungen zur Germania Slavica / Hrsg. Chr. Lübke. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998. 380 S. (Forschungen zur Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Mitteleuropa; 5.)

- Struve K. W., 1981. Die Burgen in Schleswig-Holstein. Bd. 1: Die slawischen Burgen. Neumünster: Karl Wachholtz Verlag. 115 S.

- Struve K. W., 1985. Starigard-Oldenburg. Geschichte und archäologische Erforschung der slawischen Fürstenburg in Wagrien // 750 Jahre Stadtrecht Oldenburg in Holstein. Oldenburg i. H.: Stadt Oldenburg. S. 73-206.

- Struve K. W., 1989. Starigard - Oldenburg. Der historische Rahmen // Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission, 69 (1988). Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. S. 20-47.

- Teegen W.-R., Schultz M., 2017. Starigard/Oldenburg. Hauptburg der Slawen in Wagrien. VII: Die menschlichen Skelettreste. Neumünster: Wachholtz Murmann Publishers. 608 S.

- Udolph J., 2016. Heimat und Ausbreitung slawischer Stämme aus namenkundlicher Sicht // Die frühen Slawen - von der Expansion zu gentes und nationes. Beiträge der Sektion zur slawischen Frühgeschichte des 8. Deutschen Archäologiekongresses in Berlin, 6.-10. Oktober 2014 / Hrsg.: F. Biermann, T. Kersting, A. Klammt. Langenweissbach: Beier & Beran. S. 27-51. (Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte Mitteleuropas; 81/1.)

- Unverzagt W., Schuldt E., 1963. Teterow. Ein slawischer Burgwall in Mecklenburg. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. 135 S.

- Wiethold J., 1998. Studien zur jüngeren postglazialen Vegetations- und Siedlungsgeschichte im östlichen Schleswig-Holstein. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt. 365 S. (Universitätsforschungen zur Prähistorischen Archäologie; 45.)