Assessment of the antibiotic resistome pattern of bacteria isolated from poultry faeces

Автор: Guha S., Misra S., Ghosh B.

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

An exclusive investigation was conducted to assess the antibiotic-resistance properties of bacteria isolated from poultry faeces, with the primary objective of understanding the composition and prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance in poultry breeders. Fresh poultry faecal samples were collected from various poultry farms for analysis. The preliminary findings indicated the presence of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Recognizing the significant threat posed by antibiotic resistance to both animal and human health, especially due to the excessive use of controlled antibiotics in animal husbandry, efforts were made to isolate and evaluate antibiotic-resistant bacteria from the faecal samples. It was observed that 41% of the bacteria exhibited resistance, with specific colonies identified as 17, III, IV, 16, and II. Notably, three bacterial colonies, namely 17, III, and IV, demonstrated multi-drug resistance, highlighting the urgent need for effective strategies to mitigate contamination and curb the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in poultry environments.

Antibiotic resistance, food safety, colony-forming units (cfus), poultry faeces, public health implications

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143184707

IDR: 143184707

Текст научной статьи Assessment of the antibiotic resistome pattern of bacteria isolated from poultry faeces

The poultry industry has emerged as one of the leading global industries due to the escalating demand for poultry meat, eggs, and related products, driven by the rapidly increasing population (Guan et al., 2017). Recognized as an excellent source of high-quality protein and essential nutrients for a healthy and balanced diet (Davis et al., 2018), poultry farming involved the rearing and raising of various bird species to obtain meat and eggs, either on a commercial or domestic scale. Chicken Poultry farms, constituting the cornerstone of avian commercial farming, utilized diverse farming systems such as free cages and battery cages. The Indian poultry population has reached approximately 500 million, generating over 12 million tonnes of manure (Ibrahim et al., 2019). Despite various constraints, poultry farming in India has shown significant progress over the past decade, making it the most efficient enterprise in the livestock sector for augmenting the supply of red proteins, fats, minerals, and vitamins. India had secured the position of the world's third-largest egg producer (FAO). Poultry meat had become the fastest-growing component of global meat demand, and poultry manure was commonly employed as fertilizer in agricultural fields (Syed et al., 2020). However, it was noted that poultry faeces, acting as carriers of human pathogens, required attention to prevent pollution (Kiambi et al., 2021).

Various antibiotics were reported to have been historically used in poultry for promoting growth and preventing or treating infections (Singh et al., 2019). Antibiotics such as aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamycin, neomycin, spectinomycin, and streptomycin), penicillins (e.g., penicillin and amoxicillin), nalidixic acid, ampicillin, tetracycline, and colistin were commonly incorporated into poultry feed (Ajayi and Omoya, 2017). The application of antimicrobials had raised global concerns about the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Poultry litter, potentially contaminated with various microorganisms, including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi, posed risks of transmission to animals, humans, and the environment. Antibioticresistant bacteria in faecal samples were particularly worrisome, indicating the development of antibiotic resistance through various mechanisms (Muhammad et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2016). This resistance could occur through various mechanisms, such as: 1) Spontaneous genetic mutations could be undergone by bacteria, rendering them resistant to certain antibiotics. These mutations might occur naturally over time or as a consequence of exposure to antibiotics. 2) Genetic material, including antibiotic-resistance genes, could be transferred to other bacteria by bacteria through mechanisms like conjugation, transformation, or transduction. This facilitates the spread of antibiotic resistance among different species of bacteria. The development of antibiotic resistance could be contributed to the overuse or inappropriate use of antibiotics. 3) The unnecessary or incorrect use of antibiotics could provide selective pressure for the survival and proliferation of resistant bacteria (Hermana et al., 2020).

In addition to the risk of microbial contamination, concerns persisted about the transmission of multidrugresistant bacteria due to the sub-therapeutic use of antimicrobials for prophylaxis or acting as growth promoters in poultry farms (Hamed et al., 2021). The misuse of antibiotics in various scenarios affected bacterial responses to treatment, fostering the development of multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria, which could potentially be transmitted to humans indirectly through the consumption of poultry or poultry by-products (Yasharth and Das, 2021). Consequently, the objective of this study was to monitor the antibiotic resistance profile of bacteria in chicken faeces in the southern part of West Bengal, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Collection:

Faeces samples were collected from a total of five locations (Diamond Harbour, Joka, Jagatpur Bazar Kestopur, Baguiati VIP Market, Tollygunge & Joykrishnapur Chairi Village) from Southern part of South West Bengal, India (Table 1; Fig 1). Faeces samples obtained from the poultry farm in Joykrishnapur Chairi Village, located in the Sonarpur subdivision of South Twenty-Four Parganas district in West Bengal, India. This area, known for its substantial poultry farms, plays a crucial role in meat production, and the local population heavily relies on poultry-related activities. The study was designed to assess the prevalence of different bacteria in chicken faeces in this area and determine the antimicrobial sensitivity profile against bacteria associated with poultry. A total of three samples of 45-day-old fresh female chicken faeces were collected in autoclaved conical flasks. Among these samples, sensitive and antibiotic-resistant bacteria were identified. A total of 41% of bacteria displayed resistance at different antibiotic concentrations, with 25% exhibiting multi-drug resistance. Upon analysis, it was observed that the poultry faeces sample had shown proper and adequate bacterial growth, indicating a diverse microbial community in the environment.

Isolation of bacteria from the sample

The sample was collected and subjected to the Double dilution method. The sample was diluted from 10-1 to 10-10. A quantity of 1 gm of the sample was taken into a test tube and suspended in 9 ml of sterile saline. The sample was thoroughly mixed, and 1 ml of the sample was transferred to 9 ml of sterile saline. The sample was appropriately mixed, and successive dilutions were performed until reaching a dilution factor of 10-10. Subsequently, 100 µL of each dilution was spread on an agar plate, and the plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C in an incubator. Colonies were counted on the following day. The calculation of the CFU value for the sample was carried out using the formula CFU/ML =NO. OF COLONIES × DILUTION FACTOR

AMOUNT OF INOCULATION

Screening of antibiotic resistance bacteria

Screening for antibiotic-resistant bacteria was deemed an important process in healthcare and research settings to identify the presence and prevalence of bacteria that had developed resistance to antibiotics. Various methods were commonly employed for screening antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including:

Antibiotic Resistance Testing

A standard laboratory technique was employed, involving the cultivation of bacteria in the presence of various antibiotics to ascertain their susceptibility or resistance. Antibiotic-containing nutrient agar plates, comprising Ampicillin, Neomycin, Streptomycin,

Tetracycline, Amoxicillin, Nalidixic Acid, and Colistin at concentrations ranging from 50 µg/mL to 100 µg/mL, were prepared. Isolated single colonies from the mother plate were then transferred to the respective antibiotic plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C in the incubator. It was observed that both antibiotic plates exhibited the presence of corresponding antibiotic-resistant bacteria, indicating their true resistance to the respective antibiotics. Subsequently, the colony-forming unit (CFU) value of the resistant bacteria was calculated using the prescribed formula:

CFU/ML = NO. OF COLONIES × DILUTION FACTOR AMOUNT OF INOCULATION

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Testing:

The determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was conducted through a laboratory procedure aimed at establishing the lowest concentration of an antibiotic capable of inhibiting the growth of a specific microorganism. A series of test tubes, containing varying concentrations of antimicrobial agents ranging from 25 µg/mL to 300 µg/mL, were prepared. To each tube, 30 µL of bacteria was added using a micropipette, and the corresponding volume of antibiotic was introduced based on the concentration. The tubes were then incubated overnight at 37 °C. Following a night of incubation, visible growth was observed in each tube. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the antibiotic agent that completely inhibited visible growth.

Gram staining of antibiotic resistance bacteria

Gram staining was a commonly employed laboratory technique for classifying bacteria into two major groups, Gram-positive and Gram-negative, based on differences in the structure of the bacterial cell wall. However, information about antibiotic resistance was not provided by Gram staining, as its primary purpose was determining bacterial morphology and cell wall characteristics. The staining procedure involved several steps: A glass slide was coated with a small sample of the bacterial culture and allowed to air dry. The bacterial cells on the slide were gently fixed in place by heating. Crystal violet, a purple dye staining all the cells on the slide, was then flooded onto the slide. Iodine solution, acting as a mordant and forming a complex with crystal violet to enhance staining and improve dye retention within the cells, was applied. A decolourizing agent, such as alcohol, was briefly washed over the slide in a step that differentiated between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Gram-positive bacteria retained the crystal violet-iodine complex, while Gram-negative bacteria were decolourized. Safranin, a red dye staining the decolourized Gram-negative bacteria, was then applied to the slide. Gram-positive bacteria remained purple due to the strong retention of crystal violet. Following the completion of the Gram staining procedure, bacteria were observed under a microscope, with Gram-positive bacteria appearing purple and Gramnegative bacteria appearing red.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Approximately 41% of bacteria found in faecal samples were identified as being resistant to various antibiotics

The total CFU (colony-forming unit) count of bacteria in faeces could vary greatly depending on various factors such as the individual's health, diet, and the presence of any gastrointestinal disorders (Fig 3). The total CFU count of bacteria in faeces was 12 × 1011 CFU/ml. This meant that there could be billions to trillions of bacteria present in faecal matter. It's worth mentioning that the majority of bacteria in faeces were harmless or even beneficial, playing important roles in digestion and the maintenance of gut health. However, some harmful pathogens might have also been present, albeit in much smaller quantities.

Approximately 25% of bacteria isolated from faecal samples were found to be multi-drug resistant

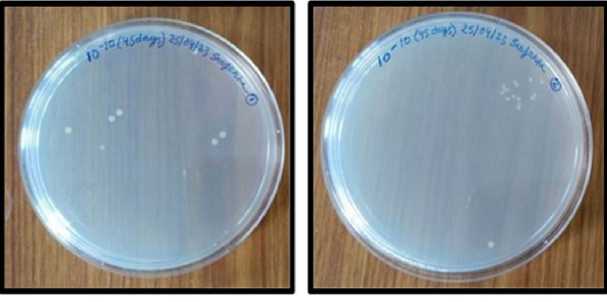

Amoxicillin-resistant bacteria, numbered 17, III, and IV, Nalidixic Acid-resistant bacteria, numbered 16, and streptomycin-resistant bacteria numbered II, were identified among them. Colistin-resistant growth was observed in bacteria numbered 17, III, and IV, rendering them multi-drug resistant (Table 2; Fig 4).

Single Antibiotic Resistance Bacteria = 5 × 1011 CFU/ML Multi Drug Resistance Bacteria = 3 × 1011 CFU/ML

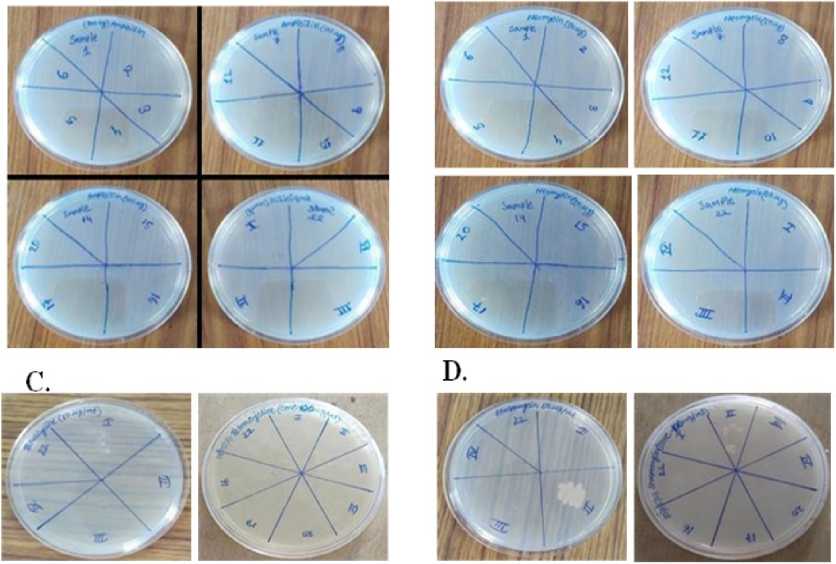

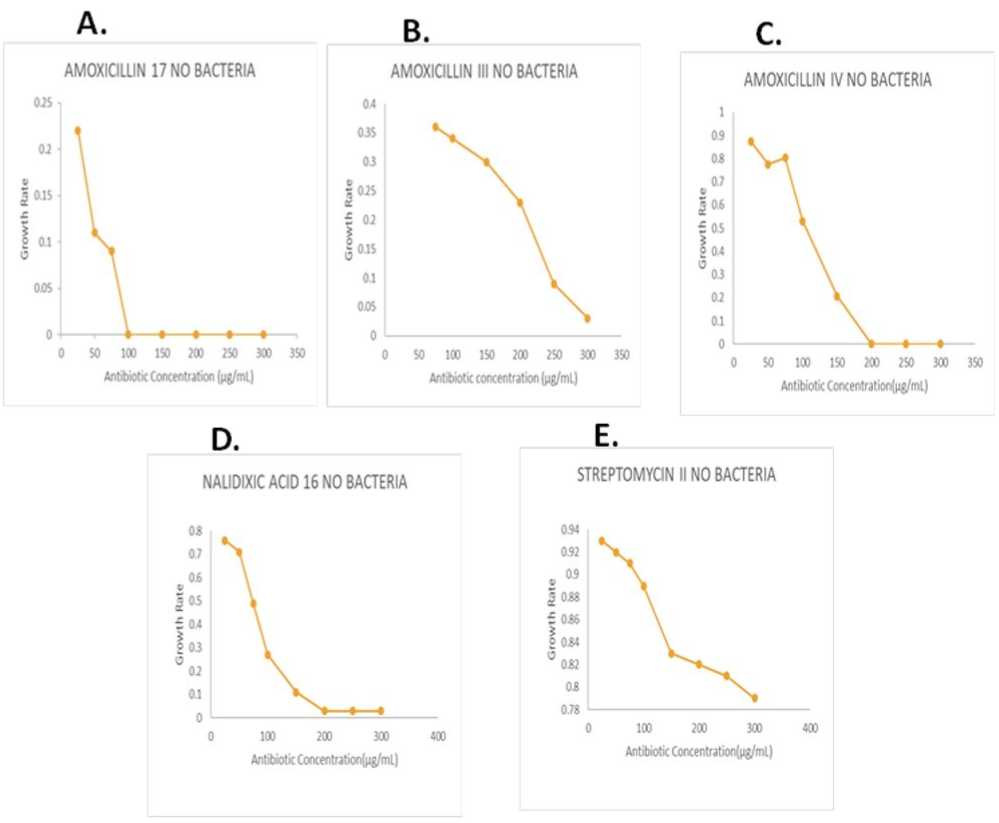

The MIC values of amoxicillin, nalidixic acid, and streptomycin against resistant bacteria were found to be quite high

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) was measured as an indicator of the effectiveness of an antimicrobial agent against a specific bacterium. It was represented by the lowest concentration of the antimicrobial agent that inhibited the visible growth of the bacterium (Table 3). The MIC value of streptomycin against resistant bacteria was found to be quite high. A high MIC value indicated that a higher concentration of the antimicrobial agent was required to inhibit the growth of the resistant bacteria (Fig 5).

The Gram character of the antibiotic-resistant bacteria

Antibiotic resistance in bacteria sourced from poultry faeces was posed as a significant public health concern. Antibiotics were often administered to promote growth and prevent disease among the livestock on poultry farms, leading to the development of resistant bacterial strains. These bacteria could be transmitted through contaminated poultry products or environmental exposure, potentially causing difficult-to-treat human infections (Shazali et al., 2014). Efforts to mitigate this issue involved promoting responsible antibiotic use in agriculture, implementing strict hygiene measures in poultry production, and developing alternative strategies to reduce reliance on antibiotics. Addressing antibiotic resistance in poultry faeces was crucial to safeguarding both animal and human health (Ge et al., 2021). In this study, the impact of seven antibiotics - Ampicillin, Neomycin, Streptomycin, Tetracycline, Amoxicillin, Nalidixic acid, and Colistin - on poultry faecal samples was investigated. Findings revealed that bacterial resistance emerged in four antibiotics, specifically Amoxicillin, Streptomycin, Nalidixic acid, and Colistin, with concentrations ranging between 50 µg/mL to 100 µg/mL. Of the bacterial samples analyzed, five exhibited antibiotic resistance (Samples no- 17, III, IV, 16, II), with three demonstrating multidrug resistance (Samples no17, III, IV) (Zige and Omeje, 2023 . This highlighted that approximately 41% of bacteria within the faecal samples were resistant to various antibiotics, with around 25% displaying multidrug resistance. Observations, as depicted in Figures 4 and 5, illustrated the resistance patterns of bacteria isolated from the faecal samples across different antibiotics and concentrations. The number of colonies observed varied significantly based on the antibiotic type and concentration employed (McMurry et al., 1998).

The MIC testing was proceeded with. MIC testing, abbreviated for Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, was a pivotal procedure used to ascertain the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent required to inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism. This assessment was instrumental in evaluating the efficacy of antibiotics or other antimicrobial substances against various pathogens (Kelley et al , 1998). Following Figures 6 and 7, the MIC values of different antibioticresistant bacteria alongside their corresponding antibiotics were observed, and the MIC value range for each sample was presented: For sample 17, no bacterium demonstrated resistance to amoxicillin, with MIC values ranging from 75µg/mL to 100µg/mL. Sample III, no bacterium displayed resistance to amoxicillin, with MIC values ranging from 250µg/mL to 300µg/mL. In sample IV, no bacterium exhibited resistance to amoxicillin, with MIC values ranging from 150µg/mL to 200µg/mL. In Sample 16, no bacterium displayed resistance to nalidixic acid, with MIC values ranging from 150µg/mL to 200µg/mL, and Sample II did not exhibit high resistance to streptomycin. This organized presentation facilitated clear comprehension and interpretation of the MIC testing results for each antibiotic and sample (Ajayi and Omoya, 2017 .

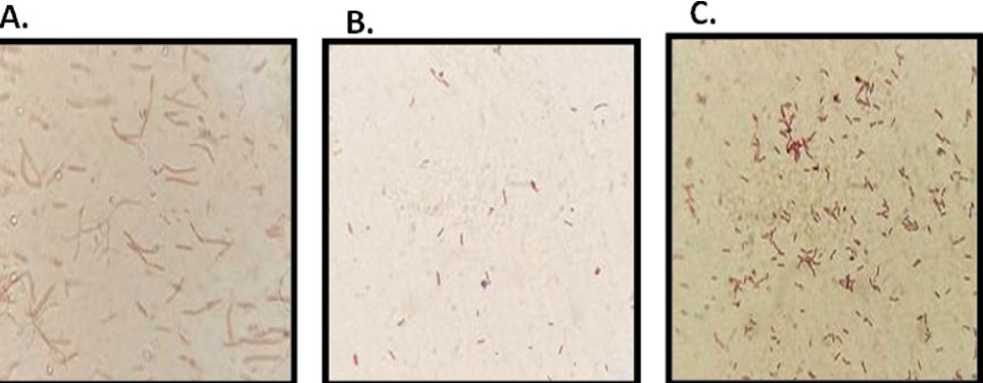

Gram staining was proceeded with. Gram staining was considered a pivotal technique in microbiology, serving as a cornerstone for differentiating bacteria into Gram-positive and Gram-negative groups based on their distinctive cell wall compositions (Islam et al , 2017). This method held significant importance in various aspects of microbiological studies, including diagnosis, treatment selection, and the elucidation of bacterial characteristics. By swiftly identifying the Gram character of bacteria, Gram staining facilitated the prompt determination of appropriate therapeutic strategies and further avenues for research (Bogaard et al. , 2002). Following Figure 8, our examination revealed the Gram characteristics of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Among these, Amoxicillin 17 no bacteria exhibited, which were identified as gram-negative, small rod-shaped bacilli. Similarly, Amoxicillin III and Amoxicillin IV no bacteria showed, yet they were characterized as gram-positive, small rod-shaped bacilli. Nalidixic acid 16 no bacteria displayed, identified as gram-negative with sphericalshaped cocci. Lastly, Streptomycin II no bacteria presented, which were gram-negative and exhibited spherical-shaped cocci (Hassan et al. , 2014 .

Table 1: Collection of poultry faeces from different locations

|

Date of Sample Collection |

03/03/2023 |

11/03/2023 |

16/03/2023 |

21/03/2023 |

26/03/2023 |

|

Temperature |

34 °C |

37 °C |

37 °C |

38 °C |

37 °C |

|

Collection Area |

Diamond Harbour Joka |

Jagatpur Bazar Kestopur |

Baguiati VIP Market |

Tollygunge |

Joykrishnapur Chairi Village |

|

Collection Time |

03:25 pm |

09:45 am |

10:05 am |

04:15 pm |

05:55 pm |

|

Latitude |

22.4533° N |

22.3555°N |

22.6108° N |

22.4986° N |

22.437682° N |

|

Longitude |

88.3025° E |

88.2554° E |

88.4272°E |

88.3454° E |

88.347552° E |

|

Chicken Age |

13 Days & 40 Days |

40 Days |

43 Days |

45 Days |

45 Days |

|

Sex |

Male & Female |

Female |

Male |

Male |

Female |

|

Faeces Type |

Separate hard lumps, soft blobs with clear-cut & fluffy pieces with ragged edges |

Fluffy pieces with ragged edges |

Soft blobs with clear-cut |

Soft blobs with clear-cut |

Fluffy pieces with ragged edges |

|

Faeces Quantity |

150-200 gm |

200-250 gm |

100-150 gm |

100-150gm |

150-200 gm |

|

Isolation Done |

Performed |

Performed |

Performed |

Performed |

Performed & identified |

Figure 1. The sample collection areas were designated as follows: [A] Diamond Harbour Joka, [B] Jagatpur Bazar Kestopur, [C] Baguiati VIP Market, [D] Tollygunge, [E] and [F] Joykrishnapur Chairi Village.

ABC

Figure 2 . The types of faeces were characterized as follows: [A] Hard lumps were separated, [B] Soft blobs with clearcut shapes were formed, and [C] Fluffy pieces with ragged edges were observed.

Figure 3 . The total colony-forming unit (CFU) count of the bacterial colony plates was determined to be 10-10

Table 2: Bacteria isolated from the faecal sample were found to be resistant to different antibiotics.

|

SI NO |

Antibiotic |

Concentration |

Sample 16 |

Sample 17 |

Sample I |

Sample II |

Sample III |

Sample IV |

|

1 |

Ampicillin |

100 µg/mL |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

2 |

Neomycin |

50 µg/mL |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

3 |

Streptomycin |

50 µg/mL |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

|

100 µg/mL |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

||

|

4 |

Tetracycline |

50 µg/mL |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

100 µg/mL |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

5 |

Amoxicillin |

50 µg/mL |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

100 µg/mL |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

||

|

6 |

Nalidixic Acid |

50 µg/mL |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

100 µg/mL |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

7 |

Colistin |

50 µg/mL |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

100 µg/mL |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

Figure 4. No colonies were observed on ampicillin (100µg/ml) [A], neomycin (50 µg/ml) [B], and tetracycline (50 & 100 µg/ml) [C]. Furthermore, II no colonies were detected on streptomycin (50 µg/ml) as well as (100 µg/ml) [D], 17, III, & IV no colonies additionally, appeared on amoxicillin (100 µg/ml) [E], and 16 no colonies showed on nalidixic acid (100 µg/ml) [F]. Furthermore, 17, III, & IV no colonies were observed on colistin (100 µg/ml) [G].

Table 3: Displayed the MIC values of the different antibiotic-resistant bacteria in their corresponding antibiotics.

|

Antibiotic |

Sample No |

Blank |

Contro l |

25 µg/mL |

50 µg/mL |

75 µg/mL |

100 µg/mL |

150 µg/mL |

200 µg/mL |

250 µg/mL |

300 µg/mL |

|

Amoxicillin |

17 |

.00 |

.26 |

.22 |

.11 |

.09 |

.00 |

.00 |

.00 |

.00 |

.00 |

|

Amoxicillin |

III |

.00 |

.51 |

.49 |

.46 |

.36 |

.34 |

.30 |

.23 |

.09 |

.03 |

|

Amoxicillin |

IV |

.00 |

.993 |

.874 |

.775 |

.803 |

.531 |

.207 |

.00 |

.00 |

.00 |

|

Nalidixic Acid |

16 |

.00 |

.87 |

.76 |

.71 |

.49 |

.27 |

.11 |

.03 |

.03 |

.03 |

|

Streptomycin |

II |

.00 |

.97 |

.93 |

.92 |

.91 |

.89 |

.83 |

.82 |

.81 |

.79 |

Figure 5. [ A ] The 17 no bacterium was found to be amoxicillin-resistant, with a MIC value ranging from 75µg/mL to 100µg/mL. [ B ] The III no bacterium exhibited amoxicillin resistance, with a MIC value ranging from 250µg/mL to 300µg/mL. [ C ] The IV no bacterium demonstrated amoxicillin resistance, with a MIC value ranging from 150µg/mL to 200µg/mL. [ D ] The 16 no bacterium was identified as being resistant to nalidixic acid, with a MIC value ranging from 150µg/mL to 200µg/mL. [ E ] The II no bacterium was characterized by high resistance to streptomycin.

Table 4: Morphology of the different antibiotic-resistant bacterial isolates

|

ISOLATE |

MORPHOLOGY |

|

AMOXICILLIN 17 NO BACTERIA |

Gram Negative, Small Rod Shape, In Pair Appearance |

|

AMOXICILLIN II NO BACTERIA |

Gram Positive, Small Rod Shape, Singlet Appearance |

|

AMOXICILLIN IV NO BACTERIA |

Gram Positive, Small Rod Shape, In Pair Appearance |

|

NALIDIXIC ACID 16 NO BACTERIA |

Gram Negative, Spherical Shaped, Small, In Pair Appearance |

|

STREPTOMYCIN II NO BACTERIA |

Gram Negative, Spherical Shaped, Small, In Pair Appearance |

D. E

^^^—^^^-^^^—^^^^ ■—

Figure 6. [ A ] Amoxicillin 17 no bacteria, which were gram-negative, small rod-shaped bacilli. [ B ] Amoxicillin III no bacteria, which were gram-positive, small rod-shaped bacilli. [ C ] Amoxicillin IV no bacteria, which were grampositive, small rod-shaped bacilli. [ D ] Nalidixic acid 16 no bacteria that were gram-negative and had sphericalshaped cocci. [ E ] Streptomycin II no bacteria, which were gram-negative and had spherical-shaped cocci.

The high prevalence of multidrug-resistant bacteria in poultry was reflected as a reservoir of resistance in birds that could also be transmitted to humans. If these resistant organisms to antimicrobials persisted, there would have been a great problem of antimicrobial choice in the near future. Proper efforts were deemed necessary to reduce or check the prevalence of resistant bacteria in farms, including the adoption and implementation of guidelines for the prudent use of antimicrobial agents in animals used for food (Salehizadeh et al , 2020).

CONCLUSION

In this study, a diverse range of bacteria was successfully isolated from poultry faeces, revealing that a complex microbial community comprising bacteria is harboured in poultry faeces. The results indicated the presence of a high percentage of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in poultry faeces, suggesting the existence of antibiotic-resistance genes that could be transferred to other non-pathogenic and pathogenic bacteria in the environment. Antibiotic resistance had become a significant concern in modern society, exacerbated by the common practice of using antibiotics in poultry farms to promote growth and prevent diseases in the birds. However, this practice was found to contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in poultry. The use of manure from these farms as fertilizer in agriculture posed a risk of spreading antibiotic-resistant bacteria to the soil, crops, and ultimately, the food chain. Exposure of consumers to these antibiotic-resistant bacteria through contaminated food could unknowingly does the infections that were difficult to treat with antibiotics. Addressing antibiotic resistance in poultry farming requires transdisciplinary systematic efforts, with the government playing a crucial role in implementing regulations and guidelines to ensure the responsible use of antibiotics in the poultry industry. Monitoring and controlling antibiotic usage had been essential to limit the development and spread of antibiotic-resistant genes among bacteria in poultry farms. Promoting alternatives to the routine use of antibiotics, such as probiotics and improved hygiene practices, had also been identified as measures to reduce reliance on antibiotics and decrease the risk of antibiotic resistance.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

We, hereby, confirm that the research is original and has not been published nor under consideration in any journal. This study did not involve the handling or rearing of any animal subjects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors are indebted to the Principal, Bidhannagar College, Kolkata for providing the necessary infrastructural and laboratory facilities to conduct the experiments and research work. Thanks are due to the Heads of the Department of Microbiology and Zoology of Bidhannagar College, Kolkata for extending collaborative research. The authors are also indebted to the local people associated with the respective poultry farms for collecting the samples.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.