Boris Lavrov, the commander of the first Lena expedition

Автор: Shestakova Tatyana P.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Economics of the Northern communities. Politology

Статья в выпуске: 20, 2015 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article is devoted to the life of Boris Lavrov, an Arctic explorer, one of the directorsof the Northern Sea Route Headquarters, the organizer of the Igarka port construction and Kara expeditions, the commander of the First Lena expedition, unjustifiably repressed and executed. Much attention is paid to the First Lena expedition aimed at sending ships with cargoes from Arkhangelsk to the Lena River delta.

The Northern Sea Route, the development of the Far North, the First Lena expedition, Boris Lavrov

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318711

IDR: 148318711 | УДК: 332.1/332.02 +32

Текст научной статьи Boris Lavrov, the commander of the first Lena expedition

Recently we have seen the opening of new oil fields in the platform “Universitskaya-1” in the northern part of the Kara Sea. But a hundred years ago, the number of ships, managed to pass the waters of the Kara Sea, did not exceed a few dozens. Today's success in the development of the Arctic comes after a great number of expeditions. The names of some of the employers we know, the others remain unknown or almost forgotten. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) played an important role in the development of economic activities in the Arctic.

A huge contribution to the development of the Northern Sea Route has been made by our country in 1930s. In 1920, Committee of the NSR was established in order to develop the way through the Kara Sea to the mouth of the Ob and Yenisei and establish economic relations with European countries. In 1928, the Committee was transformed into the North-Siberian State JSC of the Transport and Industry “Komsevmorput”. Its Chairman was Boris Lavrov. He controlled the construction of the port of Igarka on the Yenisei, the organization of Kara expeditions and in 1933—1934 he was the leader of the first Lena expedition aimed at shipping cargoes from Arkhangelsk to the mouth of the Lena River. The aim of this article is to give to the memory of Boris Lavrov, the person who had made a considerable contribution to the development of the Arctic, and probably could had done even more if political repressions of the 1930s—1940s did not cut short his life1. Economic development, northern societies, the Northern Sea Route, Arctic expeditions and politics closely intertwined in his life and tragic fate.

The first attempts to explore the Northern Sea Route

One of the first attempts to cross the Kara Sea and reach the mouth of the Yenisei River, was the expedition on the schooner “Ermak” in 1862 under the command of Pavel Pavlovich Kruzenstern (1834—1871). His schooner was trapped in the ice of the Kara Sea. So the team was forced to leave it and walk until they could reach the land2. Expedition was funded by the merchant Mikhail Konstantinovich Sidorov (1823—1887), born in Arkhangelsk and then he moved then to Krasnoyarsk 3. Failure of P. Kruzenstern did not stop M.K. Sidorov, who offered an award of two thousand pounds to the first man who would go along the Northern Sea Route and reach the mouth of the Ob and Yenisei. The first man to prove the possibility to go along the NSR was a British Captain J. Wiggins (1832—1905), who started the merchant shipping through the Kara Sea on the ship “Diana” and several times reached the mouth of Ob and Yenisei Rivers 4. The next important step was the expedition to the Yenisey in 1875 and 1876 of the famous Swedish Arctic explorer Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1832—1901), funded by M.K. Sidorov and a Swedish merchant A. Dixon [1, p. 661]. The island in the Yenisei Gulf was named Dixon in his honor. In 1878—1879 on the vessel “Vega” N. Nordenskiöld was the first to pass from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean with one wintering and returned back to Sweden through the Suez Canal [1, p.661]. The vessel “Vega” was escorted by the ship “Lena” till the mouth of the Lena River, which then went up the river and arrived in Yakutsk.

In 1893—1896 expedition of the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen (1861—1930) on the ship “Fram” went via Northern Sea Route from Norway to New Siberian Islands. Its aim, however, was not the way to the Pacific Ocean, but failed attempt to reach the North Pole. In 1913 F. Nansen on board of vessel “Correct” went from Tromsø (Norway) to the mouth of the Yenisei [1, c. 604].

Among other famous expeditions: Russian Polar expedition in the 1900—1902 on board of “Zarya” under the leadership of a geologist, a polar explorer Baron Eduard Vasilyevich Toll (1858— 1902). The objectives of the expedition were extensive and included detailed study of the New

Siberian Islands and the search for a hypothetical Sannikov Land. The fate of this expedition was tragic. In 1900 difficult ice conditions forced E. Toll to stay for all winter in the Kara Sea, and the second stay was on the New Siberian Islands. All members of the E. Toll’s crew who decided to walk to the islands, died, and they are still not found [2, 3].

Two more famous expeditions — by a naval officer George Lvovich Brusilov (1884—1914 or 1915) on the sailing steam schooner “Saint Anna”5 and by a geologist and Arctic researcher Vladimir Alexandrovich Rusanov (1875—1913?) on a small motor-sailing boat “Hercules” (captain — A. Kuchin). Both expeditions took place in 1912, had a task to pass along the Northern Sea Route from the East to the West, and both ended tragically [1, p.109, p. 823]. The year 1912 was extremely unfavorable for sailing in the Arctic Ocean because of difficult ice conditions. In the same year expedition on ships “Taimyr” and “Vaigach” had an attempt to go from Vladivostok to St. Petersburg. They could reach Cape Chelyuskin, but heavy ice fields forced the expedition to return to Vladivostok [2, 3].

In 1913—1915 hydrographic expedition under the command of a polar hydrographer Boris Andreevich Vilkitsky (1885-1961) on ships “Taimyr” and “Vaigach” managed to make a second expedition after N.A.E. Nordenskiöld through the Northern Sea Route. In 1913, the expedition failed to break beyond Cape Chelyuskin and it had to return back to Vladivostok. The first voyage from Vladivostok to Arkhangelsk happened in 1914—1915 with one wintering off the coast of Taimyr [1, c.149]. As a result, the expedition discovered new islands in the Arctic Ocean and officially declare them the property of Russia.

The third voyage (after N. Nordenskiöld and B.A. Vilkitsky) was made by Norwegian polar explorer and traveler Roald Amundsen (1872—1928) on the schooner “Maude” with two wintering in 1918—1920 [1, c.31].

In 1932 in the Soviet Union there was voyage through the northern seas during a single navigation on the icebreaker “Sibiryakov”. The leader of the expedition was Otto Ulevich Schmidt (1891—1956), research onboard was led by Vladimir Yulevich Wiese (1886—1954), who participated in the expedition of Georgy Sedov in 1912—1913, and wrote a fundamental book “Soviet Arctic Sea” [2].

The expeditions listed above were implemented by enthusiasm of the northern pioneers and were exploratory mostly. But in 1920s—1930s the task of establishing a regular navigation in North revealed. It was necessary to deliver cargoes to the mouth of the Ob, the Yenisei, the Lena and other Siberian rivers, shipping of timber and other goods from Siberia to European ports.

Since 1920 shipping in the mouth of the Ob and Yenisei, known as Kara operations, had been started. In 1932, Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route was established and got the basic functions of “Komsevmorput”. B.V. Lavrov, at the time — a member of Chief Directorate, presented a draft on transfer of cargo ships from Arkhangelsk to the mouth of the Lena River. The passage presented in the draft is known as the First Lena Expedition.

Boris Lavrov: before and after the revolution

Boris Lavrov born on the 21st of October 1886 in the village of Feodoritskoe, Rybinsky Uyezd of the Yaroslavl Province in the family of a priest. Village of Feodoritskoe does not exist now — it was near the confluence of the Volga and Mologa and was flooded after the construction of the Rybinsk power plant and the Rybinsk Reservoir. He studied in the Yaroslavl Theological seminary. In the beginning of the 1900s, Boris Lavrov joined the revolutionary movement and had been an active member of the Bolshevik Party since 1903.

Lavrov involved his fellow from the village school N.A. Uglanov in political work. Later, this per-son became a prominent figure of the October Revolution and had responsible positions in the Party and Government in the 1920s. Uglanov wrote in his autobiography [4]: “my fellow and friend from the school, the son of a priest of our village, Boris Vasilevich Lavrov, had been studying at the Yaroslavl seminary and had already been a social democrat…I remember specific moments. B.V. Lavrov arrived for the Christmas

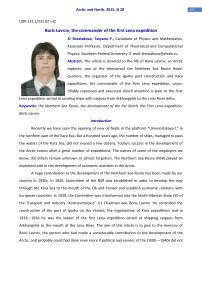

Picture 1. Boris Vasilevich Lavrov holidays, had brought a lot of literature, Resolutions of the II Party Congress and explained me in details all the reasons for the split that took place at the Congress. He announced himself a Bolshevik and a supporter of Lenin...”. For the revolutionary activities Lavrov was expelled from the seminary. Later on, he studies at the Kazan University and was also expelled and sent into exile to Arkhangelsk province under police surveillance.

In 1912—1913 he worked with V.I. Lenin for the newspaper “Pravda”, in 1915—1917 was working on the fronts of the First World War. Lavrov had been on the side of revolution, but, apparently, he had doubts on political issues. During the Civil War, he had left the Bolshevik Party, and returned back in 1920. He tried to practice for the good of his country and had leadership skills, fully manifested in his work on the economic development of the North.

After October 1917 Lavrov was sent to the Narkomprod, in 1918 was regional prodcom-missar in Vyatka. In the 1920s he worked in the Narkomvneshtorg in Central Asia and the North Caucasus. He served as a Trade Representative of the USSR in Afghanistan. The jurisdiction of the Commissariat was JSC “Komsevmorput”. In 1928 he became Chairman of the JSC “Komsev-morput” and B.V. Lavrov was involved in the development of the North. The objectives of the JSC were to construct factories, mines, shipyards in the upper reaches of the Ob and Yenisei. In 1929— 1931, construction of Igarka port was the main business of the JSC “Komsevmorput” and its Chairman.

Igarka

Separate attempts to organize operation of the Northern Sea Route were made by Russian and foreign businessmen before the October Revolution. In 1911 Russian, British and Norwegian manufacturers created joint-Siberian Stock Company for this purpose. Activity of the company attracted even F. Nansen [5, 6]. In 1913 he sailed on a cargo ship “Correct” from Norway to the mouth of the Yenisei, partly repeating the path of “Fram” in 1893. Then Nansen traveled to Siberia and the Far East. Back home he wrote the book “In Siberia”, which was published in Russian in 1915 with the title “In the country of the future” [7]. The book emphasized the thought of F. Nansen that the development of vast riches of Siberia was a task for the future, but not for the present time.

In 1916 the construction of the port of Ust-Yenisei began. It was 310 km from the mouth of the Yenisei. However, in the navigation period it was flooding. Its reconstruction required a lot of time and enormous costs that would prevent the upcoming release of Siberian goods on the world markets. Therefore, in 1927—1928 the Yenisei River was studied in order to determine the best location for construction of the port. Such a place was Igarka duct, formed by a deep bend of the Yenisei River [3]. On its banks the construction of a timber processing plant, the city and the port began.

In spring 1929 B.V. Lavrov came to Igarka. In that year the first house had been built and the construction of a sawmill № 1 had been started. The plant was opened in November and the first cargo ships came to Igarka. Two hundred people were wintering there. Work continued during the polar night, despite the hard conditions: permafrost, cold, sometimes reaching – 60 C. The builders faced enormous difficulties; it was actually the first experience in such conditions.

The soil became hard as a rock, then turned into a swamp; building materials subjected to deformations which had not been described in the engineering literature.

The following year, the port of Igarka welcomed more ships. Two thousand people were wintering there, and a year later — twelve thousand. In 1931 in Igarka three sawmills were built. It took three years to build two-story houses instead of tents and huts. Igarka became a town. Shops, schools, stadium and club appeared there.

Boris Lavrov supervised the construction of Igarka not from the Moscow office. He was in Igarka with builders, was involved in the fusing of the forest, and appeared on unfinished berths. He gained enormous prestige among the people, he led. He also studied, received special knowledge, which helped to make the right decisions.

Lavrov was the head of “Komsevmorput” and therefore was responsible not only for construction of Igarka, but also for the implementation of marine operations in the Kara Sea. In 1930, the first sailing directions of the Kara Sea were released together with a detailed map. Instead of separate expeditions there were pre-planned cargo ships sailing there. Port of Igarka gained international importance. Ships began to arrive from Western Europe for Siberian wood materials to Igarka. Foreigners, who were visiting Igarka, were surprised by its growth. People wrote a lot about it in our country and abroad.

In 1935 a special “Arctic” issue of the journal “Technology for the youth” was published and it was devoted to the development of the Arctic and the Northern Sea Route. The journal also published the article by B. Lavrov about the construction of Igarka [8].

The First Lena

The next natural step was to spread the cargo transfer to the mouth of Lena River. In order to achieve this, the ships had to overcome the most difficult part of the Northern Sea Route — round the Taimyr Peninsula and cross the Laptev Sea. In 1930, Lavrov organized an expedition on the schooner “Beluga”, aimed at sailing around the Taimyr Peninsula, but heavy ice conditions did not allow this to happen. In 1932 Lavrov presented his project to the government and explained the possibility to pass on the cargo ships to the mouth of the Lena River. Lavrov defended the project against the skeptics and had been appointed a head of the expedition.

The expedition started in 1933. It was carried out on cargo ships “Volodarsky”, “Tovarish Stalin” and “Pravda" that had to go with the other ships almost all the way but it had a task to deliver equipment necessary for geological exploration for the expedition to the south-western part of the Laptev Sea. The plan was to transfer several ships to the Lena River and from the Ob and Yenisei Rivers. Icebreaker assistance was done by the icebreaker “Krasin”.

“Krasin” came from Leningrad in July 1933, passed the Baltic Sea and went round Scandinavian Peninsula, restocked in Murmansk and want to the Strait Matochkin Shar between the North and South islands of Novaya Zemlya. They had an appointment with “Tovarish Stalin”, “Volodarsky” and “True”. But these ships went out from Arkhangelsk later because of the delay in loading. The meeting took place on the 13th of August at the east entrance to the strait and “Krasin” led cargo ships through the ice of the Kara Sea to the edge of pure water. In pure water ships reached Dickson Island on the 18th of August. The leader of the expedition arrived there by plane from Igarka. Before taking over the leadership of the expedition, he had to finish everything related to the organization of Kara operations, which were under his control.

Dixon Island

Later, Boris Lavrov himself described the expedition in his book “The first Lena”[9]. Describing his arrival to the island of Dixon, he quoted from the report of N.A.E. Nordenskiöld’s expedition, 1876: “In a short time this desert will become a meeting point for a great number of ships, which will contribute to the relations not only between Europe and Ob and Yenisei systems, but also between Europe and Northern China”. But it is for the future. Expedition is ahead. Famous predecessors’ experience was important for the expedition. Lavrov turns to the experience of F. Nansen, E. Toll and R. Amundsen. Graves of explorers, known and unknown ones are on the island. Not far from the island of Dixon, there is a grave of the P. Tessem, mem-ber of the R. Amundsen’s expedition on the schooner “Maude”. Lavrov asked himself a question: Why were people attracted by the North? Why was he attracted? And his answers were: “love to unexplored, to understanding the things had not been understood, the possibility of a broad scientific study and economic development of huge northern areas” [9].

Meanwhile, icebreakers “Rusanov” and “Sibiryakov” came to Dixon. “Rusanov” had to deliver goods to the Pronchishchev Bay on the east coast of the Taimyr Peninsula. “Sibiryakov” that in the previous year for had a historic sail along the NSR during one navigation, had to carry out scientific research in the Kara Sea. However, on the way, both icebreakers net heavy ice and had to return to Dixon. It was a concern. Due to delays with loading ships arrived at Dixon later than expected and it was the second reason for worries.

On the 23rd of August Lavrov called a Council on board the “Krasin”. The council was attended by the Chief of the expedition onboard of “Sibiryakov” Professor V.Y. Wiese, captains of “Krasin”, “Sibiryakov”, “Rusanov”, “Volodarsky”, polar pilot A.D. Alexeyev and other mem-bers of the expedition.

The main question was: What way would the ships follow? Half-way along the Taimyr Islands there are so — called Minin Skerries — an archipelago of small islands, called after a navigator named Fedor Minin, one of the leaders of the Great Northern expedition whose members described the northern coast of Russia in 1733— 1734 for the first time.

Wiese said there were three possible ways: first — the coastal one, using straits between the islands of the archipelago; the second — to the north of the archipelago, and then via Vilkitsky Strait; third way- to the north, and then to Shokalsky Strait between islands of Severnaya Zemlya.

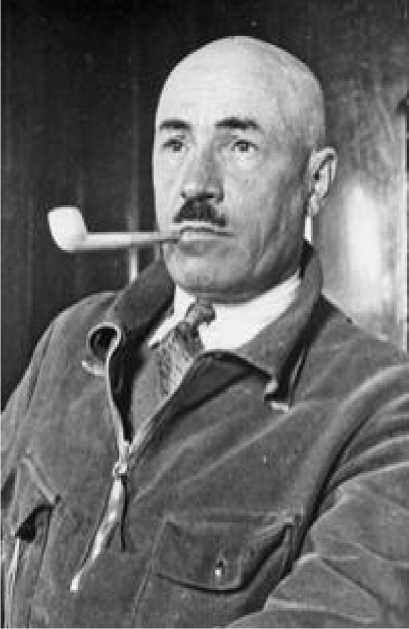

Picture 2. The map of the First Lena expedition, M.E. Singer “Lena path”

Opinions were divided. In the south of the Kara Sea there were large areas of ice. So, the northern path looked more attractive, but even riskier. Lavrov had not much experience like Wiese and polar captains. He led a polar expedition for the first time and had a full responsibility for it. At the Council it was decided to choose the second option — to go along the edge of Minin Skerries, and time had shown that solution had allowed the ships to get to the mouth of the Lena River in that navigation and avoid wintering at least on the way there.

Council on the island of Dixon was called historical — so important was the Lena expedition for the country. The meeting was recorded. The expedition was accompanied by journalists — a correspondent of the newspaper “Izvestia” M. E. Singer and a correspondent of the newspaper “Vodniy transport” S.T. Morozov. Their essays about Lena were first published shortly after these events [10, 11]. Singer, referring to the words of Lavrov, wrote that the correct option had been chosen in accordance to the Ob and Yenisei flow along the western coast of Taimyr, the thermal effect of the continent and the direction of winds, the experience of “Vega”, “Fram” and “Zarya”

expeditions [10]. Ice conditions were important as well. They had the data of air-exploration made by the pilot Alexeyev.

Morozov deserves a special mention. Savva Timofeevich Morozov — grandson and a full namesake of a well known Russian manufacturer; a young journalist who combined duties of a correspondent with duties of a fireman of the second class on the icebreaker “Krasin”, in future — a writer, honorary polar explorer, member of the Geographical Society of the USSR. Onboard of “Krasin” he made his way from Leningrad to Cape Chelyuskin, and then onboard of “Volodarsky” to Tiksi Bay. The book of essays “Lensky campaign” Morozov dedicated to “Boris Vasilevich Lavrov — the builder of the Soviet North” [11]. He met with Lavrov in Moscow before the expedition. Here's how S.T. Morozov described the leader of the first Lena expedition: “In this man there was something of the explorers — Ermak, Dezhnev, Khabarov ... Not in the appearance — but as a matter of fact. Of course, there was not a dense beard, nor clothing from animal skins or tall boots. Clean-shaven, in a light jacket and an open-necked shirt, with constantly smoking pipe in the corner of his mouth, he made impression of a typical citizen, business person, even a cracker. By the tone of how confident and slowly he picked up the phone, in concise phrases, addressed the invisible interlocutors, it was obvious that he had a great deal of cases, that his advices and instruction were waited for on the Yenisei River, where the wood rafts float, and in Leningrad on the Kanonersky island where a large icebreaker was repaired and assigned to sail to the Arctic, and in Sevastopol, where marine aviators complete a test of a new machine for a polar ice exploration...”[12].

On the 24th of August the vessels were set out. “Krasin” was making a way and was followed by timber carrier “Tovarish Stalin” damaged before arriving at Dixon and “Pravda”, then — the icebreaker “Rusanov”, timber carrier “Volodarsky” and the caravan was closed by “Sibiryakov".

Cape Chelyuskin

On the way to Cape Chelyuskin “Krasin” lost a propeller. It was a crucial moment, endangering the fate of the expedition. But, it was decided to break through the ice. On the 30th of August convoy managed to reach clean water, on the 31st of August they reached Cape Chelyuskin. At the same time, reports were received from ships “Chelyuskin” and “Sedov”: Shokalsky Strait was in ice. So, the right decision was made earlier. The path through the Shokalski Strait proved to be irresistible and ships could be jammed by ice before arrival at destination.

Chelyuskin Cape is the northernmost point of Asia with the only radiostation on the territory from Dixon to Tiksi. Wiese wrote, “Today, for the first time the Northern edge of Asia saw such a great number of vessels: seven ships were there at the same time near the polar station at Cape Chelyuskin” [2]. This is a significant place for all polar explorers. Members of the expedition visited the polar station. On the shore — a pole put by R. Amundsen in 1919 during an expedition on the schooner “Maude”. At the top of the column — a copper ball with the inscription: "To the Conquerors of the Northeast Passage Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld and his glorious companions. Expedition to the “Maude” 1918—19”. It was another reminder from great predecessors.

The ships had gone further without icebreakers. “Krasin” had to return and help riverboats. “Rusanov” followed to the Pronchishchev Bay. “Sibiryakov” stayed for loading at Cape Chelyuskin. On the boat “Tovarish Stalin” spontaneous combustion of coal had been started even before the arrival at Cape Chelyuskin. The vessel had gas, oil and dynamite for geologists onboard as well. So, fire onboard was extremely dangerous. It was decided to unload some coal at Cape Chelyuskin and upload it onboard of “Krasin” and “Sibiryakov”. Timber carrier “Pravda” went for unloading to the Bay of Noordwijk. “Volodarsky”, where the head-quarters of the expedition moved, had to go the Bay of Tiksi together with “Tovarish Stalin”.

Tiksi Bay

On the 2nd of September there was a heavy storm, which lasted until the 6th of Sep-tember. But the storm let the expedition to pass to Tiksi Bay together with the river boat “The First Five-Year Plan”. East wind drove ice from the west coast of Taimyr Peninsula, making way easier. Lavrov realized this and called the “The First Five-Year-Plan” from Dixon.

On the 8th of September, “Volodarsky” entered the harbor of Tiksi. By the time of arrival, there were no buildings, except for the two houses of the polar station. Participants of Leno-Hatanga expedition wintered there. The task of their expedition was to conduct research in the Lena Delta region and to identify the place for the new port. The ships of the First Lena expe-dition brought to Tiksi Bay a new group researchers and cargoes for the Lena-Hatanga expedition. It was possible to see part of the schooner “Zarya” used for Toll’s expedition in 1900—1902, a reminder of past tragedies. Wood, of which the schooner was made, was very strong. So, workers that wintered nearby could use it for firewood.

In the bay there were no conditions for unloading ships and were no piers. There were barges, but no tugs to take the barges to ships and to unload them in the sea. It was decided to use small boats for towing barges. But the boats turned out to be not ready. Lavrov went ashore to supervise the work personally. Unloading was done, at a great cost to members of the expedition.

On the 9th of September the ship “Tovarish Stalin” entered the Bay. A fire was in its hold, hatches were battened down to prevent the spread of fire and the deck was hot; the crew continuously cooled it with water. The rapid unloading of flammable substances started. The fire was extinguished the day after due to the pumping of water into the hold.

On the 12th of September the river boat “The First Five-Year Plan” came to the Bay. It passed from Dixon to Tiksi with the help of “Krasin” and brought a lighter (a kind of barge) used by “Volodarsky” and “Tovarish Stalin” to moor. This considerably facilitated further unloading. By the 16th of September unload had been done fully. It took one week instead of the estimated ten days, but by this time alarming reports had been arriving. Before the 10th of September Vilkitsky Strait off Cape Chelyuskin had started to cover with ice, and old ice began to transform in the large field. Here is what the chief of the expedition onboard of “Sibiryakov” Wiese wrote: "I am very worried about the Lena vessels and radioed the chief of the Lena expedition in Tiksi Bay: "The passage of ships of the Lena expedition through the Vilkitsky Strait after the 20th of September is the greatest concern even with an icebreaker”. B.V. Lavrov received daily meteorological and ice reports from the station at Cape Chelyuskin and, of course, and he was aware of the threat for Lena vessels. But it was impossible to stop the unloading — Yakut Territory needed the goods delivered from Arkhangelsk so much” [13].

The main task of the Lena Expedition was done. Establishing links with the East Siberia, which Fridtjof Nansen had left for distant future, became a matter of fact. Participants of the First Lena made it real. B.V. Lavrov discussed prospects with explorers. He said that it was possible to sail from Arkhangelsk to Kolima, that cargoes could be carried to Yakutia and back.

On the 16th of September 16 a farewell meeting was held and vessels started their way back. Correspondents left the expedition. M. Singer flew from Tiksi to Moscow on pilot Leva-nesky’s plane. Morozov went with a caravan of river vessels headed by “The First Five-Year Plan”, which brought up loads the Lena to Yakutsk. In the Bay of Tiksi the Lena-Hatanga expedition was left for wintering. They carried out the work that was the beginning of the Tiksi Arctic seaport construction (the name was approved by the NSR Board in March 1934) [14].

Wintering

On the 18th of September the vessels “Volodarsky” and “Tovarish Stalin” joined the icebreaker “Krasin”. Then the caravan was joined by the icebreaker “Rusanov”and timber carrier “Pravda”, which due to the weather conditions could not be unloaded in the Bay of Noordwijk. By the 20th of September convoy reached Vilkitsky Strait. Because of the cold, the Strait seemed to be impassable for the timber carriers, even though they were led by powerful icebreaker “Krasin”.

The situation was more difficult to the West of Cape Chelyuskin where the icebreaker “Sibiryakov” was trapped in ice near the archipelago of Nordenskiöld.

Ice conditions in the Kara Sea, as well as the delay of more than ten days because of the loading of the ships “Volodarsky”, “Tovarish Stalin” and “Pravda” in Arkhangelsk made the wintering inevitable [10]. On the 23rd of September it was decided to prepare the ships for the wintering and to let the icebreakers “Krasin” and “Rusanov” go; they could be used for other purposes, to release “Sibiryakov” of the ice trap. A place for wintering had to be chosen so that the ships were not caught by drifting ice, and the risk that the shrinking ice would crush the vessels was minimal. Thus they decided to stop for wintering place at the Samuil Islands (now Komsomolskaya Pravda Islands), near the north-eastern coast of the Taimyr Peninsula. A Selection of people staying for the winter was held: primarily those who could contribute of the expedition with strong spirit and physical endurance. The rest continued the way home onboard of “Krasin” and “Rusanov”. Boris Lavrov was then allowed to leave the wintering, as the main goal — delivery of cargoes to Yakutia — was done. But he did not consider such an opportunity.

People had to stay for almost a year in the “land of ice and night” for wintering 6. According to the memoirs of one of the members of the expedition N. N. Urmantsev, those who were left for wintering had strong negative feelings caused by leaving of “Krasin” and “Rusanov”, their heads were full of dark thoughts about the upcoming winter [16]. It was necessary to overcome such sentiments.

Due to B.V. Lavrov skill the wintering was used for scientific research in the Far North. Urvantsev, the leader of the geological group, went onboard of “Pravda” to the Bay of Noordwijk and he was appointed a leader of the scientific operation. Meteorological, hydrological, topographic studies were made and a connection with the group at Cape Chelyuskin was established.

The ships were in the ice but there was a rist that the storm could break the ice and damage the sips. So, on one of the nearby islands it was decided to build a house, station and warehouse. Other adjacent islands were explored as well.

Winterers were engaged not only in scientific research but everyday routine also. There were classes for those who wanted to study the Maritime College program. These classed allowed a sailor to become a navigator and a fireman — to become a mechanics. Teaching was done by more experienced members of the expedition; they also were the members of the Exam Commission, which, in coordination with Narkomvod order got the right to issue students diploma of the college level. Winterers had their small entertainments and even a theatre...

In Tiksi Bay the plane P-5 was taken onboard of “Volodarsky”. It was decided to use it for air exploration. The first flight was made in October 1933 to the polar station at Cape Chelyuskin. The plane was operated by the polar pilot Mauno Yanovich Lindel. Planned flights to the Severnaya Zemlya were delayed: P-5 motor was broken. Lavrov spent almost a month visiting wintering station. Later Lindel got the U-2 aircraft. He used for air exploration. The aircraft had an open cockpit. So, it was convenient for observation, since it was flying within a small speed, which allowed considering all the details of the terrain and the pilot and observers felt themselves uncomfortable in the polar conditions. A test picture 3. b.v. lavrov in 1933 flight was made to the Bolshevik Island of Severnaya Zemlya and then Lavrov and Lindel came back from Cape Chelyuskin to the wintering grounds.

A polar night was around with all its severity and beauty: light of the moon and stars, relentless game of the Northern lights... Life flowed over with a strict schedule. Sessions of radio contact with relatives that stayed away and other winterers made the life more interesting. Together with the whole country they were watching the fate of “Chelyuskin” trapped by drifting ice...

On the 30th of January 1934 the sun came out for the first time: the northern gray twilight lasted two hours. In February air exploration was resumed. Under the command of N.N. Urvantsev an expedition deep into the Taimyr was prepared and conducted [16]. The expedition lasted 21 days, from the 20th of March to the 9th of April aimed of topographical survey and tests in arctic conditions. Off-road vehicles crossed the northern part of the Taimyr from the Gulf of Teresa Klavenes (the name was given by R. Amundsen during the expedition of 1918-1920) to Mogilny Cape where two members of the Vilkitsky’s expedition 1914—1915 on the ships “Taimyr” and “Vaigach” were buried. Then their route lay along the Taimyr coast to Cape Chelyuskin, and then — to the place of the wintering through the Maud Bay where Amundsen wintered in 1919.

Training plane U-2 could fly only a short distance. In order to expand the range of flights, an additional petrol tank was installed. The winterers began to explore near the island of Malyi Taimyr and the eastern shores of Severnaya Zemlya. B.V. Lavrov constantly served as a pilot observer. The flights were not without accidents. May 11, 1934: due to the strong wind the aircraft was off the course. Visibility dropped to zero, but Lindel managed to land the plane. They were twelve to fifteen kilometers from the ships. After a while they decided to walk. Then the blizzard increased, and the wind changed and its direction gave the landmark. The outlines of objects and distances were distorted due to refraction (bending of light rays in the atmosphere). In icy conditions, without clear guidelines, it is very easy to get lost and freeze. The path to the ships took twelve hours with a few stops for rest. According to the words of one winterer, Lavrov and Lindell “looked straight into the jaws of the polar death”.

On the 26th of May they flew to the Pronchishchev Bay, where the wintering hunters were. The flight was risky, since at the Pronchishchev Bay and on an airplane there was no radio. In case of an accident it was impossible to rely on help. Sunny weather changed to the foggy one, but there was no hope for the better weather conditions. They flew along the the east coast of Taimyr. The fog forced to land several times.

Lavrov wrote about one of the forced landings: “We landed in a deep snowy ravine ... landing place is not known exactly. It should be somewhere between the Andrey islands and the islands of Peter, at East Taimyr Cape” [9]. Due to the fog it was possible to leave this place the day after.

Despite the risks, Lavrov would complete ice exploration, before the new navigation season and the sailing of the second convoy to the Lena River. The convoy supposed to sail from the East to West along the Northern Sea Route guided by the icebreaker “Fyodor Litke”. Eastern District of Taimyr had not been covered by air exploration before. In order to get the full picture, it was necessary to make a flight to Severnaya Zemlya. The plan was to visit the wintering on the Domashny Island. This tiny island, which could only be found on a topographic map, is a part of the Sedov’s islands, belonging to the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago.

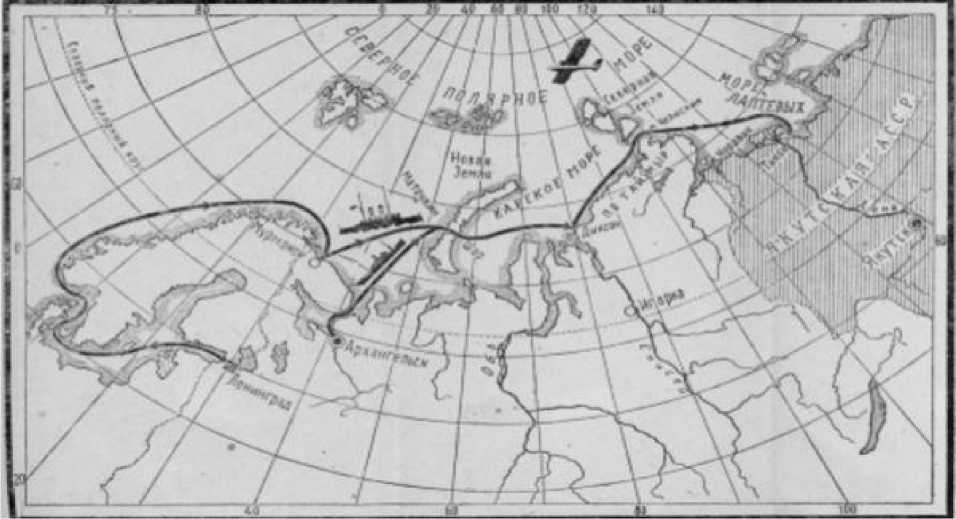

Picture 4. Ice cover near the North-East coast of the Taimyr Peninsula in 1933 according to the air observations during the First Lena expedition (from the B.V. Lavrov’s book “The First Lena”).

The islands were discovered in 1930 by the expedition on the icebreaker “Sedov” and until 1937 were called Kamenev Islands. Then they were renamed in honor of the vessel that discovered them. On the 12th of June Lavrov and Lindell flew from Cape Chelyuskin to the Severnaya Zemlya. During flight there was a serious accident.

On the way home

The flight had to be from Cape Chelyuskin to the northwest across the Vilkitsky Strait, to the Cape Neupokoev and Bolshevik Island. Then the plane flew over the Shokalsky Srtait, along the Krasnoflotskie Islands, Snegnaya Bay, Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya Island and Gamarnik Cape (since 1937 — Cape Copper). After Gamarnik Cape, one of the cylinders of the engine failed. Lindell was able to land the plane, but he could not fix the motor. There was no hope for help. It was impossible to organize the search with dogs and vehicles because of the polar summer conditions. They had to survive and get out of this situation by themselves. First of all it was necessary to resolve the issue: to return by foot to Cape Chelyuskin or to go to the wintering on the Domashniy Island? The first way was familiar, well-versed, and easy not to go astray. But the distance to Cape Chelyuskin, of not less than three hundred kilometers, excluded this option.

The Domashniy Island was in about 150 km. It is extremely difficult to find a small point among thousands square kilometers of white lifeless space. “I remember many of the polar journeys of sailors and Arctic explorers after losing their vessels,” — writes Lavrov [9]. “How many were ended well? Few, though many of them were better equipped than we did” [9].

Picture 5. Approximate route Lavrov and Lindel followed until the Domashniy Island in June 1934 (reconstructed according to the B.V. Lavrov’s book “The First Lena”)

Lavrov and Lindel had no special preparation for such a situation. Lavrov wrote about Lindel: “In the wintering camp everyone knows that he was trained to fly perfectly and at the same he is a bad walker for long distances” [9]. Some experience of walking along the polar ice had been gotten during the winter. But that that moment the conditions are even worse. In the polar summer conditions, the snow started to melt; it was snow on the surface and the thin ice under that did not withstand human weight. Feet fail and fall on the sea ice, covered with a layer meltwater. It was almost impossible to find a dry place to put a tent. Light tent does not hold heat and get wet. Clothing, shoes, blankets — all became wet and there was no hope to dry them.

They made the sled out of the top cover of the fuselage. On the 15th of June Lavrov and

Lindel spent a night on almost dry soil of Cape Krzhizhanovsky. The next day they saw islands at the sea. They got a hope that this was the Kamenev archipelago. Therefore they made an attempt to go there directly. The attempt failed. The Gulf of Stalin was next on the road (Now – Panfilovtsev Gulf). It was important to cross it and get on its northern shore to shorten the path.

But the road was extremely difficult. The lack of clear guidelines, short stops in the wet tent, fog that was hiding the sun so it was impossible to determine the time. When the sun was up it was hot, pain in the eyes and sunglasses do not help.

B. V. Lavrov had been writing a diary. Several times there were confident that they had already reached the Eastern Island of the Kamenev archipelago, but confidence turned out to be wrong. Only on the 24th of June Lavrov and Lindell had reached that island and after comparison with the map doubts disappeared. Then it was necessary to go along the islands of the archipelago. On the 25th of July they crossed a large bay and got to the Sredniy Island.

They were exhausted. Gloomy thoughts were is their heads. They were worried about the ice cover of the strait that separated the Domashniy Island. Lavrov wrote: “depletion and general decline of physical forces can put an end to our further work. Of course, we will still fight for a different outcome; it is early to give up”. They did it. On the 27th of June they came to the wintering on the Domashniy Island.

End of the expedition

Wintering of the First Lena expedition and research done by its participants received the highest rating. In June 1934 Chief of the Northern Sea Route O. Schmidt sent a telegram: “... I have heard a lot about your wonderful work, about you, who managed to turn a wintering into a brilliant scientific expedition to study the North Asia ...”[17].

Lavrov was awarded the Order of Lenin. And also that was the yeas when five years of Igarka was celebrated. The decision of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR, 25th of July 1934: “Noting the huge work carried out by Comrade Lavrov Boris Vasilevich on the creation and construction of Igarka, organization of the Kara expeditions and Lena expedition in 1933, and also his energy and perseverance in carrying out scientific research during the wintering of the Lena expedition, the Central Executive Committee of the USSR states: to award Comrade Lavrov Boris Vasilevich the Order of Lenin for his contribution to the exploration of the Arctic”[11].

That time Lavrov was still on the Domashniy Island. Polar station was built there in 1930— 1932 by the G.A. Ushakov’s expedition. The expedition included four people, including N.N. Urvantsev. Coastlines of the Severnaya Zemlya islands had not yet been mapped by that time. In two years, participants of the expedition managed to do it, except for the northernmost Schmidt

Island. It was found out that the Shokalsky Bay discovered by Vilkitsky’s expedition was actually a strait.

In 1932, the icebreaker “Rusanov” brought a new team to the polar — four people headed by woman-polar explorer N.P. Demme. In 1933, the icebreaker “Sedov” had to bring a new group of wintering there. However, as we already know, the ice conditions in 1933 were difficult and icebreaker “Sedov” was not able to come to the island. Demme’s group stayed there for the second winter, which was hard due to the lack of provision. In spring three out of four people had been sick. Hunting for bears helped a bit. Lavrov and Lindell had to deliver means against scurvy there. But it was not possible to do. Lavrov and Lindell came there. They were totally exhausting and saw those people in a difficult situation. They took over the hardest work — cleaning of the territory. Their own clothes and boots turned into rags, but they had nothing to replace them. They waited for the arrival of the icebreaker “Sadko”, but it was trapped by ice. It soon became clear that “Sadko” would not come.

A real threat of a third winter became clear too. Finally, on the 30th of August 1934 a plane, piloted by A.D. Alexeyev landed. The aircraft delivered six people and fifteen dogs to Cape Chelyuskin. Winterers were taken on board of “Sibiryakov”. For one of winterers, seriously ill with scurvy, help came too late — the day after he died.

They had to leave dogs because there was no place for them on the plane. There was a hope that new group would come but it never happened. However, the head of the expedition Nina Demme managed to take the three cats and a kitten in a suitcase. She brought cats with her two years ago, and a kitten was born during the wintering.

Nature and animals were described a lot in the book about the First Lena expedition by Boris Lavrov. He watched the northern dogs, mentioned birds — gulls and snow Buntings-occasionally pleased polar explorers with their visit. The author revealed as a man, carefully observing the nature and, at the same time, anxious about the fate of natural wealth of our country. Lavrov participated in the hunt for the bear many times but he was sorry when a bear was killed not because of the vital needs, but only to fulfill a hunting passion. He talked about the “senseless murder” and warned against the risk of destruction of bears and walruses populations; underlined the need to develop hunting rules in the Far North.

Meanwhile the icebreaker “Fyodor Litke” went along the Northern Sea Route from Vladivostok to Murmansk. It was given the task released the first Lena expedition’s ships [13]. Head of the research on “Fyodor Litke” was Professor V.Y. Wiese. On the 12th of August “Fyodor Litke” approached the northern entrance to the strait between the Samuil Islands; the strait was covered with ice. “Fyodor Litke” was different from the other icebreakers that split ice by pushing it with their bow. “Fyodor Litke” ice could cut the ice by a frontal bow shock. Five days and “Fyodor Litke” made a channel of nine km length towards the ships of the first Lena expedition; after that the bow was completely broken but the ships were released. Timber carrier “Pravda” went to the Noordwijk Bay for unloading, and “Volodarsky” with coal — to Bay of Tiksi. “Tovarish Stalin” and “Fyodor Litke” went to Dixon. On the way back “Volodarsky” and “Pravda” met “Sibiryakov” at Cape Chelyuskin. By this time there Lavrov, Lindel and winterers from the Domashniy Island had been there. Vessels of the Second Len expedition came from the West led by the icebreaker “Ermak”. After meeting them “Sibiryakov”, “Volodarsky” and “Pravda” left the Cape Chelyuskin, and three days after reached Dixon. The First Lena expedition was completed.

According to S.T. Morozov, back in Moscow Lavrov celebrated his second birthday on the 27th of June, when he and Lindel reached the Domashniy Island [12]. “In this situation I'm supposed to live no less than one hundred years”, — he said. A short time was left to live ... Just a few years of normal human life before his arrest.

Several years after the Lena expedition

In 1935 B.V. Lavrov became a director of the Research Institute of Economy of the North. In the short time he managed to recruit many specialists and organize research. One result of this activity is, for example, the book by Sibirtsev and Itin “The Northern Sea Route and Kara expeditions” with Lavrov’s foreword and reduction [3].

Lavrov could not stay at the Institute, he wanted some practical activities. Back in 1933 an exploratory expedition led by N.N. Urvantsev was sent to the Noordwijk Bay. Urvantsev and his team had to spend winter with the ships of the first Lena expedition; in 1934 the icebreaker “Rusanov” brought them to Noordwijk Bay. Development of oil fields in the area looked promising. In addition, in the Noordwijk Bay some other mineral were found — coal and salt. With the active participation of B.V. Lavrov the draft of the “Nordvikstroy” project was pre-pared. Lavrov became its leader.

The objective of the trust was to conduct geological exploration, field development, construction of the city and the port. Plans were no less ambitious than in construction Igarka. However, Lavrov had no chance to do it.

Political repressions

Lavrov B.V. was arrested as head of the trust “Nordvikstroy”. By that time N.A. Uglanov, his schoolmate and friend had been arrested and killed. Geologist N.N. Urvantsev, captain of

“Volodarsky” N.V. Smagin and other people who knew him at work in the Arctic had been arrested as well. According to the NKVD report, published on the “Memorial” website, Lavrov was exposed by the statements of Uglanov, Urvantsev and others. Today, we know how these statements were written. He was charged as a member of anti-Soviet Right-Trotskist organization, where he was involved by Uglanov. In addition, Lavrov was said to be involved in sabotage activities at the trust “Nordvikstroy”7. On the 6th of July 1941 Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court sentenced Lavrov to death. He was shot on the 28th of July 19418.

Boris Lavrov’s brothers were arrested. Dmitry Vasilevich Lavrov, teacher of mathema-tics and physics at school in Rybinsk, was accused of leading peripheral counterrevolutionary organization, which he created after the instructions of Uglanov. He was shot. Alexei Vasilevich Lavrov, hydraulic engineer, chief engineer at “Gidroelektroproekt” in Rostov-on-Don, spent two years in prison. However, the charges against him were not proved and in 1940 he was released. All brothers were recognized as victims of political repressions.

After NKVD archives had been declassified, Boris Lavrov’s relatives got a chance to look through the documents. At the end there was a petition for clemency attached. According to his daughter Natalia Borisovna Lavrova9, the petition was written on the 7th of July 1941 (the day after sentencing) — a clear handwriting, set out on two pages, logically sustained. It says that he (B.V. Lavrov) had never taken part in the counterrevolutionary organizations and he had never been a threat; he had never refused from hard work that he was assigned to by the party and government. Further — where and how he worked in the Arctic, and at the end — “... I’m asking to save my life”. In content it was not a petition for clemency, but the appeal for a ret-rial. Apparently, he had a desire to leave a paper, which would clarify what had happened, and there were no hope of preserving life under those circumstances.

Memory

In 1972 a bay in the Laptev Sea on the Taimyr Peninsula was called in honor of Lavrov [18, 19]. The title was awarded by Khatanga District Executive Committee on the proposal Hydrographic Enterprise of the Ministry of the Navy and Hatangsky hydrobase on the 2nd of March 1973 and was approved by the decision of the Krasnoyarsk Krai Executive Committee. This is the same bay where Lavrov and Lindell had a forced landing of the 26th of May 1934, “somewhere between the islands of Andrew and Peter”. This small bay can be found only on the topographic map, its coordinates — 76° 40’ north latitude, 111° 30’east longitude.

Journalist and writer S.T. Morozov did alot to preserve the memory of Boris Lavrov. He wrote a series of articles and a book “The ice and people” where B Lavrov is represented under the name Yegor Bagrov [20]. In 1964 Morozov visited Igarka. Then, it was its thirty-five year anniversary. Talking to Chairman of the City Council, he mentioned Lavrov, but it turned out that the Chairman did not hear anything about Lavrov [21]. After that, Morozov expressed his opinion about the need to keep the memory of the man who organized the construction of Igarka in a great number of publications. “There must be Boris Lavrov’s street in Igarka!” — he said at the end of the article in the newspaper “Krasnoyarsk Rabochiy” published in 1987 [12]. After the publication in late 1987 Igarka City Council decided to name one of the streets in honor of B. Lavrov, taking into account the wishes of the citizens10.

Boat “Boris Lavrov”

A boat built in 1980 was named in honor of Boris Lavrov. It was widely discussed in the press. Articles about the person whose name appeared on the board of a boat were published in a great number of newspapers: starting from a regional Tiksi newspaper “Mayak Arktiki” [17] and ending up by the article in “Izvestiya” written by Saava Morozov [23]. Symbolically, “Boris Lavrov” was assigned to the port of Tiksi and carried cargoes along the Northern Sea Route. It is an iceclass ship, which could go to the Arctic seas from Murmansk to Anadyr and enter the Arctic rivers such as Lena and Kolyma.

According to the lists of vessels, placed on the website “Water transport”, in July 1993 the boat was owned by OJSC IC “Arctic Shipping Company”. In 2009, the company transferred the ship to the foreign company ARSCO. Shortly thereafter, the sailors stopped receiving any salary, went to Court and even demanded the arrest of the vessel. In September 2010, “The Arctic Shipping Company” was declared bankrupt, and its ships, including “Boris Lavrov”, were auctioned. The new owner of “Boris Lavrov” is LLC IC “Vega” and its new port is Vostochniy. In April 2011, the ship got new name “Alexsandr”11. Renaming a ship when it enters a new owner — is not uncommon. However, it is a special situation. Once on board the ship the name of Boris Lavrov have erased, a piece of history of our country has disappeared. People saw the name on the board, someone (not everyone) wondered who a man that gave the name of the ship was and what he did. Can a “speaking nothing” name "Alexander" encourage someone to continue the work of the Arctic exploration, which requires the efforts of many dedicated people? It is quite obvious that the answer is no.

Picture 6. The boat “Boris Lavrov”. Beginning of 1980s.

What made the owners to change the name of the ship is unknown. Were they not aware of Boris Lavrov’s fate, or did not they want to have a name of a person who used to be called “Bolshevik of the Arctic” on a board of their ship? The ship is still working now. However, it does it not in the northern latitudes, but in the Pacific Ocean. But the name of Boris Lavrov disappeared from the boat. As if he was again a subject of repressions.

Conclusion

The article was aimed to show the connection between economics and politics through the prism of the life and fate of one of the Main Directorate of the Northern Sea Route leaders, the organizer of the Igarka port construction, Kara expeditions and chief of the First Lena expedition. The goal — to pay tribute to Boris Lavrov, the man who had made a considerable contribution to the development of the Arctic, has been reached. The article introduces the activities, character of B.V. Lavrov, conditions of life and work, difficulties he faced while managing the Arctic expeditions, development of the Northern Sea Route in the 1920—1930s.

We are talking about a man whose life was tragically cut by political repression, the author avoids dry presentation. At the same time, all contained in the article is based on documentary, supported by references that could be tested.

What conclusions could be made after discussing the life and destiny of B.V. Lavrov? Of course, the society is obliged to preserve his memory, as well as the memory of thousands of other people who devoted their life, strength and professional competence for economic development of the country and were tragically affected by years of political repressions. At the same time it must be mentioned that value of a human life was, unfortunately, very low that time. The high price of life itself, the incredible efforts of many Soviet people created a powerful industrial base, new sea ports and developed transport communications for the years ahead and determined the socio-economic development of the Arctic region, ensured the delivery of goods to the remote areas of the Far North and the welfare of the population living there. All this was paid for dearly.

Список литературы Boris Lavrov, the commander of the first Lena expedition

- Severnaya entsiklopediya [Northern Encyclopedia]. Moscow, Evropeyskie izdaniya, 2004. 1198 p.

- Vize V.Y. Morya Rossiyskoy Arktiki [Seas of the Russian Arctic]. Moscow, Paulsen, 2008. T. 1. 242 p. T. 2. 318 p.

- Sibirtsev N., Itin V. Severnyy morskoy put i karskie ekspeditsii [The northern sea route and Kara expedition]. Novosibirsk, 1936, 232 p.

- Uglanov N.A. Avtobiografiya. [Autobiography] Deyateli SSSR i revolyutsionnogo dvizheniya Rossii. [Memebers of the Soviet and Russian revolutionary movement]. Moscow, 1989. pp.165—176.

- Nansen-Kheyer L. Kniga ob ottse [A book about father]. Leningrad, 1986. 512 p.

- Kalvari G. Gorod na Severe [The town in the North]. Novosibirsk, 1931. 70p.

- Nansen F. V stranu budushchego: Velikiy Severnyy put iz Evropy v Sibir' cherez Karskoe more [To the country of the future: great northern route from Europe to Sibir through Kara Sea]. Petrograd, 1915. 456 p.

- Lavrov B.V. Gorod Zapolyarya [Polar City]. Tekhnika — molodezhi, 1935, no. 12, pp. 76—79.

- Lavrov B.V. Pervaya Lenskaya [The first Lena]. Moscow,1936. 288 p.

- Zinger M.E. Lenskiy pokhod [Lena path]. Leningrad, 1934. 88 p.

- Morozov S.T. Lenskiy pokhod [Lena path]. Moscow, 1934. 120 p.

- Morozov S.T. Bol'shevik Arktiki [The Bolshevik of the Arctic]. Krasnoyarskiy rabochiy. 24.09.1987.

- Wize V.Yu. Vladivostok — Murmansk na “Litke” [Vladivostok-Murmansk on “Litke”]. Leningrad, 1936. 156 p.

- Mikhaylov B.M. Rozhdenie porta Tiksi [Birth of the Tiksi port]. Letopis Severa [Northern Chronicles]. T. 11. Moscow, Mysl, 1985.

- Nansen F. V strane lda i nochi [On the land of ice and night]. St. Petersburg, T.1., 1897. 320 p. T. 2, 1898. 344 p.

- Urvantsev N.N. Taymyr — kray moy severnyy [Taimyr — my northern land]. Moscow, Mysl, 1978. 238 p.

- Melnikov A. Zdravstvuy, «Boris Lavrov»! [Hello, “Boris Lavrov!”]. Mayak Arktiki. 15.08.1981.

- Avetisov G.P. Imena na karte Arktiki [Names on the map of the Arctic]. St. Petersburg, 2009. 623 p.

- Popov S.V. Morskie imena Yakutii [Sea names of Yakutiya]. Yakutsk, 1987. 168 p.

- Morozov S.T. Ldy i lyudi [Ice and people]. Moscow, 1979. 288 p.

- Morozov S.T. Shiroty i sud'by [Latitudes and faiths]. Leningrad, 1967. 208 p.

- Polyarnye gorizonty [Polar horizons]. Vol. 3. Krasnoyarsk, 1990. 368 p.

- Morozov S.T. Skvoz ldy i gody [Through ice and ages]. Izvestiya. 03.10.1981.