Breathing plants: analyzing air pollution’s effect on leaf and stomatal morphology

Автор: Prithviraj P.S., Reshmi G.R.

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Urban air pollution has emerged as a critical environmental issue, posing significant risks to both human health and the natural environment. Among various environmental stressors, air pollution stands out due to its pervasive nature and detrimental impacts on urban flora. Plants, as integral components of urban ecosystems, are constantly exposed to pollutants such as particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and ozone. These pollutants can cause a range of physiological and morphological changes in plants, affecting their growth, development, and overall health. This study investigates the impact of air pollution on the morpho-anatomical characteristics and stomatal index of plant species growing in polluted and non-polluted areas. The research focuses on the adaptive responses of plants to air pollution by examining changes in leaf macro- and micro-morphological traits. Significant reductions in leaf length, breadth, L/B ratio, stomata size, stomata number, stomata index, and stomata frequency were observed. A lower stomata number is suggested to be an adaptation mechanism to minimize the absorption of gaseous pollutants from the air. Additionally, stomata clogging with occluded stomata pores, induced by air pollution, was identified in three plant species. These morphological alterations serve as indicators of environmental stress, providing valuable insights into the initial detection of urban air pollution. This comparative assessment highlights the importance of monitoring morpho-anatomical changes in plants as a tool for environmental pollution studies. The alterations in the leaf morpho-anatomical traits and stomatal characteristics were profound, emphasizing their potential use as reliable indicators of urban air pollution. By systematically comparing plants from polluted and non-polluted areas, the research highlights the crucial role of these morphological changes in the early detection and monitoring of environmental stress. This comparative assessment underscores the importance of integrating morpho-anatomical studies into urban air pollution monitoring programs. The findings contribute to a better understanding of how plants adapt to polluted environments, offering valuable insights for developing strategies to mitigate the impacts of air pollution on urban vegetation.

Stomatal index, air pollution, stress, leaf morphology

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143184713

IDR: 143184713

Текст научной статьи Breathing plants: analyzing air pollution’s effect on leaf and stomatal morphology

Environmental pollution, especially the rapid decline in air quality generated by anthropogenic activities, has become an important problem in urban areas (Fenger, 2009). However, emissions of pollutants such as carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3), and especially the emission of particulate matter are threatening environmental sustainability and functionality and pose potential threats in urban areas. Air contamination has harmful impacts on plants species particularly growing on roads sides and bus stops (Rai, 2016; Krishnaveni et al., 2015). Air pollution affects both plant and human health, inducing physiological and biochemical responses. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that air pollution can contribute to about four million deaths annually worldwide. Therefore, the prediction of air conditions and reduction in pollutants in urban areas are urgently needed (Vingarzan, 2004). As urban forests can improve environmental conditions, including air quality. Compared to humans and other animals, plants are more sensitive to environmental stress and have stronger physiological, biological, and morphological responses. Therefore, understanding the physiological link between tree parameters and environmental stress can be significant for gaining visions into urban forest health and functioning (Mukherjee and Agrawal, 2018).

Plants typically express phenotypic differences in response to environmental changes and under different environmental conditions, plants allocate biomass in several organs in order to capture optimum light, water, nutrient and carbon dioxide, for its maximum growth rate. Several studies have been done in anatomy of vegetative organs under polluted condition. Turgor changes in the guard cells determine the area of stomatal pore through which gaseous diffusion can occur, thus maintaining a constant internal environment within the leaf. In plants stomata play a major role in gaseous exchange and transpiration in which stomatal control is a critical process in plant adaptation in various environments (Leghari and Zaidi, 2013). The elevation of air pollution can cause both acute and chronic damage to the anatomical, morphological (leaf number, leaf area, stomata number), physiological (pH and relative weight content) and biochemical (pigments and ascorbic acid) characteristics of plant species (Karmakar and Padhy, 2019; Kaur and Nagpal, 2017). These gaseous contaminants reduce the stomatal conductance and photosynthesis (Adrees et al., 2015).

The aim of the present study was to investigate and compare the effect of air pollution on the leaf morphology, anatomy and stomatal index of some common plants growing around the areas of polluted areas and the same plant species growing in the nonpolluted region. In this study the investigation was carried out to know the effect of environmental pollution especially on leaf properties of plants in urban and rural area because leaf is the most sensitive and exposed part to be affected by air pollutants instead of all other plant parts such as stems and roots. The information generated under the study will help to understand how pollution affects morphology and anatomy of selected plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA

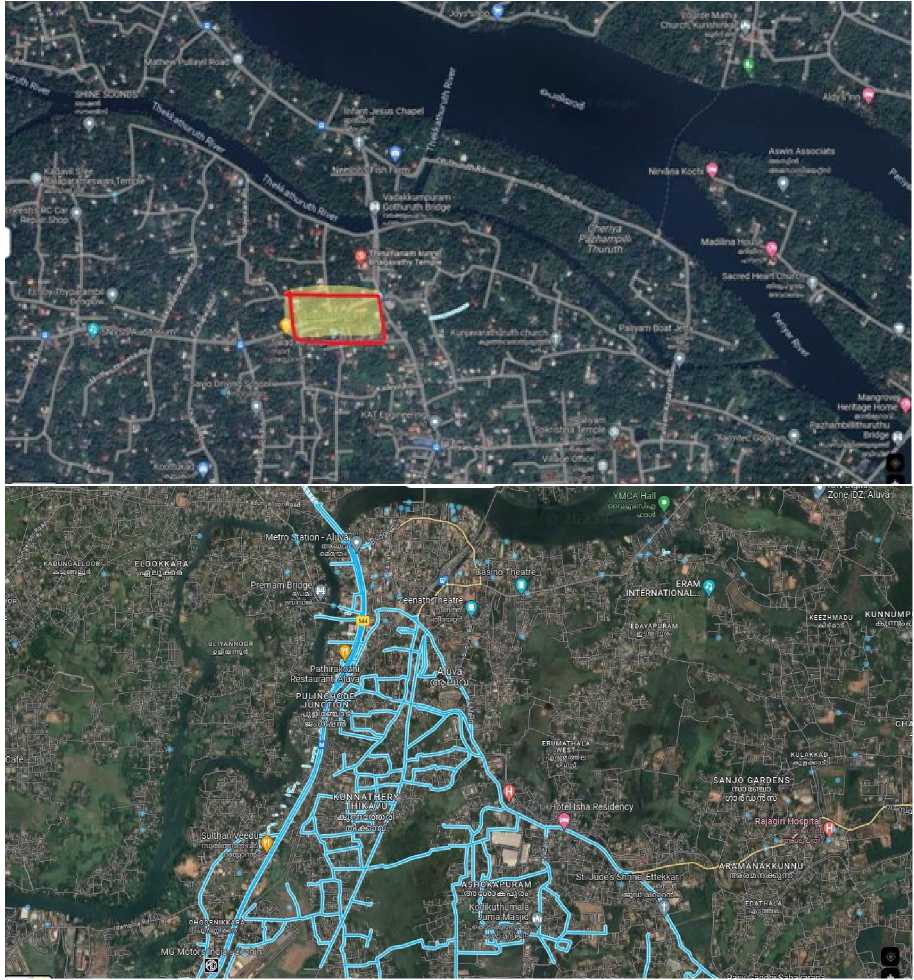

The non- polluted area under study is in an around Vadakkumpuram (Fig 1a). It is area which is rich in vegetation and biodiversity. The polluted area selected for the present study is area in and around Aluva metro station (Fig. 1b). Comparing to the metro station the respective area is less effected by air pollution and thus it is selected as the control site for this study. Plant twigs and leaf samples of five selected plant species are collected from area around Aluva metro station and alternative samples are also collected from Vadakkumpuram regions to investigate and compare the effect of air pollution on the leaf morphology and anatomy of the selected plant species.

PLANT SPECIES SELECTION AND SAMPLE COLLECTION

MORPHOMETRY STUDIES

Various macroscopic characters of the leaves of fresh plants were recorded. Leaves were collected in replicates from trees which were having uniform height and growth form. Colour, texture, and physical appearance of the leaves were analysed with naked eyes. Leaf shape and size variation is also noted. Length and breadth of leaves were measured using a ruler. Length to breadth ratio (L/B) were also calculated. The measurement of leaf length was from leaf tip along the midrib of the leaf lamina to the leaf base at the point of attachment of the lamina to the petiole. The leaf breadth was measured along the widest breadth across the lamina.

MICROSCOPIC EVALUATION

Stem anatomy

Fine sections of petioles of tree species of the selected plants were taken and stained with safranin and mounted in glycerine.

Determination of stomatal structure and stomatal index

To study the epidermal morphology, stomatal number and stomatal index of leaf, the leaf was subjected to epidermal peeling. The epidermis was peeled by hand and to prepare the abaxial surface, the leaf blade was placed on a tile or a cutting plate with its adaxial surface facing upwards. The adaxial surface was carefully scrapped with sharp razor until only the abaxial surface was left behind and all the above materials were removed with the help of camel hairbrush. The peels washed with water, placed on a clean glass slide in a drop of glycerine and followed by a cover slip over it. The slide with cleared leaf was placed on the stage of the microscope and examined under 45X objective and 10X eye piece. The number of stomata present in the area of 1sq.mm including the cell or at least half of its area within the square was counted. The average number of stomata per sq.mm was determined and their values are tabulated. Number of stomata and epidermal cell were counted per square millimeter area and the stomatal frequency and stomatal index were calculated by using the following formulae (Salisbury, 1927):

Stomatal index (SI)= S x 100 (E+S)

Where, SI - stomatal index

-

S- The number of stomata in 1sq.mm area of leaf

Stomatal frequency (S.F.) = S x 100 E

S.F – Stomatal frequency

-

S- The number of stomata in 1sq.mm area of leaf

RESULTS

Plants from polluted and non-polluted areas were collected, identified and described based on literatures. Photographs of plants collected from polluted and non-polluted areas were shown in Fig. 2 and 3.

DESCRIPTION ABOUT THE SELECTED PLANTS

Tridax procumbens L., Chromolaena odorata (L.) R. M. King & H. Rob . , Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp., Mangifera indica L., and Clerodendrum Infortunatum L. were selected for our study. Plants were identified based on the herbarium specimens, expert opinions and salient features described in the species protologues.

Tridax procumbens L.

Kingdom -Plantae

Division -Tracheophyta

|

Class |

-Magnoliopsida |

|

Order |

-Asterales |

|

Family |

-Asteraceae |

|

Genus |

- Tridax L. |

|

Species |

- Tridax procumbens L. |

Tridax procumbens is a prostrate herbaceous plant, whose flowering axis rises up to 40 cm high. It is abundantly covered with erect stiff hairs. The leaves are opposite, simple, and with dense hairs. At the end of the long stems, is a capitulum inflorescence. The fruit is topped with a tuft of white hairs.

Chromolaena odorata (L.) R. M. King & H. Rob .

|

Kingdom |

-Plantae |

|

Division |

-Tracheophyta |

|

Class |

-Magnoliopsida |

|

Order |

-Asterales |

|

Family |

-Asteraceae |

|

Genus |

- Chromolaena |

|

Species |

- Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M. King |

|

& H. Rob. |

C. odorata is a bushy plant with woody stem, and spread much branched. It can reach up to 7 m high. It is entirely covered with a pubescence. The leaves are simple and opposite. As indicated, the name of this species, its leaves give off a strong odour when crumpled. The terminal inflorescence consists of small and narrow cylindrical flower heads with white florets.

Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp

|

Kingdom |

-Plantae |

|

Division |

-Tracheophyta |

|

Class |

-Magnoliopsida |

|

Order |

-Fabales |

|

Family |

-Fabaceae |

|

Genus |

- Gliricidia |

|

Species |

- Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp |

A perennial, medium-sized (2-15 m high) legume tree. Leaves are imparipinnate; leaflets (5- 20) are ovate. The bright pink flowers is arranged in clustered racemes. The fruits are dehiscent pods, 10-18 cm long and 2 cm broad, that contain 8 to 10 seeds.

Mangifera indica L.

Kingdom -Plantae

Division -Tracheophyta

Class -Magnoliopsida

Order -Sapindales

Family -Anacardiaceae

Genus - Mangifera

Evergreen trees, to 30 m high. Leaves simple, alternate, clustered at the tips of branchlets, lamina elliptic, elliptic-lanceolate, margin entire, glabrous, shiny. Flowers polygamous, in terminal panicles. Fruit a drupe, 5-15 cm long, mesocarp fleshy, endocarp fibrous.

Clerodendrum Infortunatum L.

Kingdom -Plantae

Division -Tracheophyta

Class -Magnoliopsida

Order -Lamiales

Family -Lamiaceae

Genus - Clerodendrum

Species - Clerodendrum infortunatum L.

Clerodendrum infortunatum is a shrub that can grow from 1 - 5 metres tall. Leaves are simple, opposite; both surfaces’ pubescent, inflorescence in terminal, peduncled, few-flowered cyme; flowers white with purplish pink throat. Fruit berry, globose, turned bluish-black or black when ripe, enclosed in the red accrescent fruiting-calyx. The fruits are drupes.

MACROSCOPIC EVALUATION

The morphological parameters of plant species collected from the contaminated sites were significantly affected due to the vehicular emissions. The size of leaves is regularly declining because vehicular emissions in the study area is increasing day by day. The natural colour of the plants was also affected. Plants in polluted area was looking like a dry dead leaf with full of lesions and other patch marks, they were also covered by dust and dirt (Fig 3).

The plants in non-polluted area where fresh looking and more appealing with lesser number of lesions. The natural fragrance of the plant was much more experienced from the plants collected from non- polluted sites than in polluted sites. Plants in polluted areas seems to have lower growth than the ones in nonpolluted area. The leaves where sometimes teared and rolled inwards. The strength of stem was very less in plants in polluted area than in non-polluted area. They were looking dull and tired but the plants of non-polluted sites were looking healthy and strong. The flowers in non-polluted site plants have bright colour and fragrance than the plants in polluted area.

Leaf characteristics such as L/B ratio, and length and breadth of leaves are important factors in the assessment of air pollution. Among the selected polluted and non-polluted plants there were reduction in the width of leaf in the polluted plants. The leaf length was measured and the results revealed that there was reduction in leaf length in polluted plants when compared to non-polluted plants.

Dust particles were present on the leaf surface of plants growing in polluted area. Plant species are regularly manifested in the atmosphere and consume,

store and integrate pollutants on their leaves. Therefore, the morphological parameters of the plants collected from control site showed better growth than the polluted sites. This study showed that air pollution adversely affects plant morphology. The morphological analysis showed that the contaminated plant species undergo physical and probably functional changes to tolerate air pollution. Both the polluted and non-polluted site maximum L/B ratio was observed in Mangifera indica and minimum observed in Cleodendrom infortunatum (Table 1 ).

Figure 1. ( A ) The non-polluted site selected for the study; ( B ) The polluted site selected for the study.

A

B

Figure 2. Showing plants from non-polluted site a) Tridax procumbens b) Chromolaena odorata c) Gliricidia sepium d) Mangifera indica e) Clerodendrum infortunatum

Figure 3. Showing plants from polluted site a) Tridax procumbens b) Chromolaena odorata c) Gliricidia sepium d) Mangifera indica e) Clerodendrum infortunatum

Table 1: Showing different morphometric characters of plants growing in polluted and non-polluted

|

Tridax procumbens |

Gliricidia sepium |

Cleodendrom infortunatum |

Mangifera indica |

Chromolaea odorata |

||||||

|

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

|

|

LL (cm) |

5.2 |

2.5 |

10 |

7 |

20 |

14 |

30 |

26 |

12 |

9 |

|

LB (cm) |

2.5 |

1.5 |

5 |

3.6 |

17 |

13 |

8 |

5 |

8 |

6 |

|

L/B ratio |

2.08 |

1.66 |

2 |

1.18 |

1.18 |

1.11 |

3.75 |

5.2 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

NP: Non-polluted; P: Polluted; LL: Leaf Length; LB: Leaf Breadth; L/B ratio: Length/Breadth ratio

Table 2: Showing stomatal characteristics of non- polluted and polluted plants

|

Plant species |

Stomatal type |

stomata |

No. of epidermal cells |

Stomatal index |

Stomatal frequency (%) |

||||

|

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

||

|

Tridax procumbens |

Anomocytic |

15 |

12 |

23 |

38 |

39.47 |

24 |

65.21 |

31.57 |

|

Chromolaena odorata |

Anomocytic |

5 |

7 |

52 |

137 |

8.77 |

4.86 |

9.61 |

5.109 |

|

Gliricidia sepium |

Anomocytic |

15 |

9 |

85 |

82 |

15 |

9.89 |

17.64 |

8.53 |

|

Mangifera indica |

Anomocytic |

86 |

48 |

268 |

342 |

24.29 |

12.3 |

32.08 |

14.03 |

|

Clerodendrum infortunatum |

Diacytic and anomocytic |

25 |

14 |

109 |

139 |

18.65 |

9.15 |

22.93 |

10.07 |

NP: Non- Polluted; P: Polluted

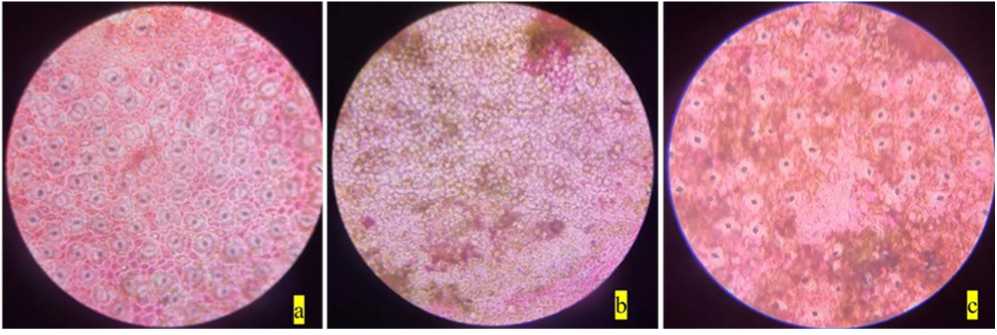

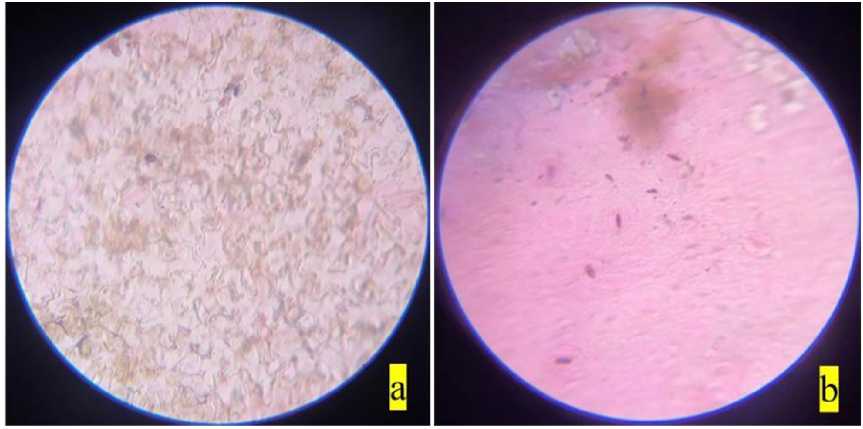

Figure 4. Stomata of Mangifera indica : a) non-polluted site; b) polluted site; c) polluted site magnified view.

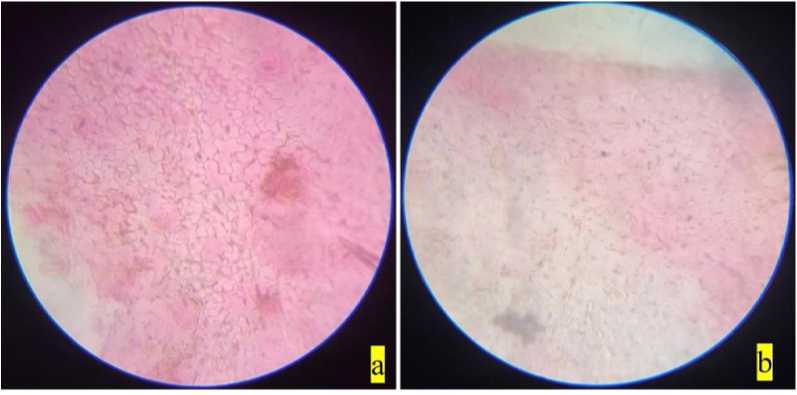

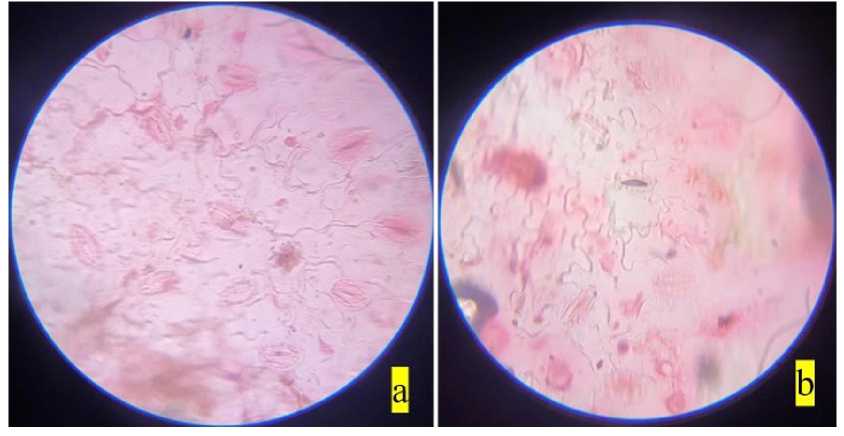

Figure 5. Stomata of Clerodendrum infortunatum : a) non-polluted site; b) polluted site

Figure 6. Stomata of Chromolaena odorata : a) non-polluted site; b) polluted site

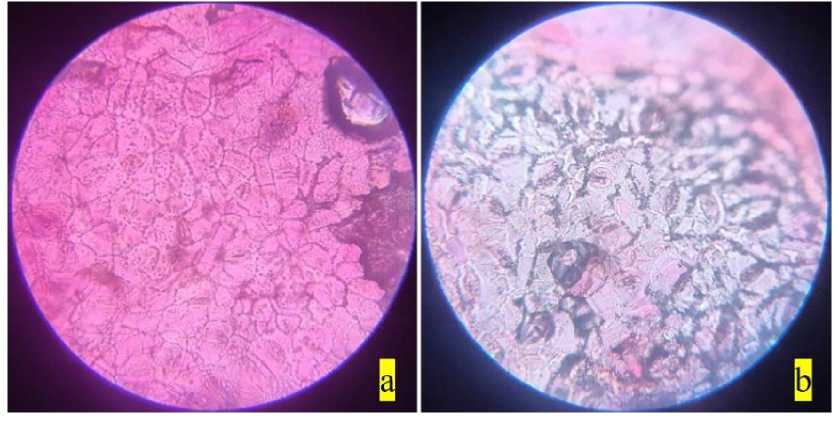

Figure 7. Stomata of Tridax procumbens : a) non-polluted site; b) polluted site

Figure 8. Stomata of Gliricidia sepium : a) non-polluted site; b) polluted site