Centralization and autonomation as the drivers of socio-economic development of the Russian Far East

Автор: Minakir Pavel Aleksandrovich, Prokapalo Olga Mikhailovna

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Socio-economic development strategy

Статья в выпуске: 6 (54) т.10, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article considers macroeconomic trends in the development of the economic complex in the Russian Far East. We explore the interaction of dynamic and structural parameters of reproduction and the specifics and regularities of promising modernization in the region. We analyze how the regional economy responds to various types of institutional impacts, and study the features of regional governmental economic policy in the east of the Russian Federation. We consider trends in external and internal impacts of economic, institutional, military and political nature. We describe formation regularities and assess sustainability trends. The aim of our research is to find the answer to the question about the possibilities and ways of transforming the socio-economic system of the Far East in accordance with the current national geo-economic paradigm. We prove that the best results in the development of the Far East were achieved in those periods when non-economic goals of the state were combined with the use of centralized material and financial resources of the state for the purpose of generating intra-regional economic and financial resources based on the support provided by government to the institutional environment that should be as comfortable as possible for the formation of endogenous reproduction within the region...

Far east, macroeconomic trends, institutions, autonomation, integration, economic growth, development, east asia

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147224001

IDR: 147224001 | УДК: 332.1 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2017.6.54.2

Текст научной статьи Centralization and autonomation as the drivers of socio-economic development of the Russian Far East

In 2013, accelerated development of the Russian Far East was proclaimed a national priority for the whole 21st century1. In 2012, Vladivostok hosted the APEC summit, which was held in Russia for the first time after its accession to this international organization in 1988. The events were preceded by another reconsideration of the geo-economic positioning of Russia in 2007–2012, which resulted in a shift of strategic focus in the development of economic interactions from the Atlantic to the Pacific direction.

In a sense, this reconsideration is a unique phenomenon in Russian economic history.

Naturally, for almost a century and a halflong history of colonization and development of the Far East, excluding the period of 1930– 1960, neighboring countries of Northeast Asia were priority partners and the sources of resources for the development of the Russian Far East. And in certain periods (1922–1928 and 1991–2000), the markets of Northeast Asia and the profit obtained through trading with them were the only factors that preserved the integrity of the region’s socio-economic system [4].

However, the eastern priority applied only to the Far Eastern economic region. The “pivot” to the East for the entire national economy2 has been marked for the first time. And this means changing the role of the Far East itself as a spatial “macroeconomic agent” of the national economy. If earlier the region was de facto, in terms of national economic development strategy, a relatively autonomous economic subject, which in varying degrees was supported by the metropolis in the resource and institutional aspect, then now it is a priority subject in national socio-economic dynamics, and the functioning of this subject should ensure the achievement of strategic goals of the national economy.

The economic complex of the region has been formed as a result of interaction of various trends and external and internal impacts of economic, institutional, military and political nature. The present paper is devoted to the description of regularities in the formation of these trends and estimation of their stability; the goal of the paper is to answer the question about the possibilities of its transformation in accordance with a new geo-economic paradigm; another goal is to evaluate critical points of application of management actions to achieve the changes desired.

Many research works study the development of the Far East at certain stages and under different institutional modes of operation; the works analyze the regional economy and its interaction with national and international economic space. In the Soviet period of the history of economic thought, the main attention of researchers was drawn to the problem of finding a rational concept for the development of the region and to the issues of optimal allocation of the productive forces, distribution and efficient use of economic resources.

These and other problematic issues including the location of production and its specialization, spatial distribution of production factors, territorial organization of the productive forces in the Far East, are examined in this article from the aspect of analyzing temporal patterns of formation and development of the region’s economic complex that explain its dynamic and structural features and prospective responses to various innovations in the field of governmental economic policy.

Stages in the formation of the regional economic system.

The beginning of colonization. 1860–1913.

Intensive economic development of the Far East began at the end of the 19th century, when the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway was launched. However, the history of economic development of the region began much earlier, almost immediately after the accession of Priamurye and the Ussuri region to the Russian Empire [1; 29, pp. 21-56]. The prime goal of building the region’s economic potential was a non-economic one: it was the establishment of a Russian military base in the Pacific area. Governmental policy of the time was focused on national expediency, rather than economic efficiency.

Already in 1861, the imperial government introduced special rules for migrants who settled in the Far East; the rules included the provision of tax and land benefits. Since 1881, new preferential rules were introduced. As a result, for the period from 1861 to 1890, about a million people moved to the Far East from the European part of Russia. This created labor potential that formed the basis of the future economic growth [9, p. 39].

Agriculture was the first sector to be developed in the region, and the degree of its marketability increased almost fivefold by 1902; it was followed by the food industry, construction materials industry, production of fur, fish and sea mammals.

By 1905, nearly 25% of all mined gold in Russia was produced in the Far East [2, pp. 4664]. Coal production increased fivefold in 1894–1903 (from 16 to 80 thousand tons). In the early 20th century, there began the exploration drilling to tap oil, and the exploration of non-ferrous metals deposits. At the time, the markets of the European part of Russia were geographically inaccessible; as a result, economic turnover of the Far East relied heavily on foreign markets. This was facilitated by the right to free trade of foreign goods granted in 1860 to the ports of Primorsky region.

The construction of the Ussuri Railway, economic growth in Russia (1907–1913) and proactive governmental policy gave a powerful impetus to economic development in the Far East. State resources were allocated in direct and indirect form (subsidies, reduced transport tariffs, provision of support to settlers, etc.). At the same time, the economic complex of the region, with the exception of state-owned enterprises satisfying the needs of the army and navy, operated autonomously on the basis of market principles and criteria. Economically, the region was fully opened, economic barriers in the western direction were alleviated with the help of state protectionist policy. As for the barriers to external communications with the Asia-Pacific Region, they were simply nonexistent. In 1913, foreign trade turnover of the Far East was more than 98 million rubles in gold, of which imports accounted for more than 76% (or over 75 million rubles in gold) [9, p. 143]. Workforce was largely formed by legal and illegal immigrants from China.

As a result of the concentration of capital, including foreign capital, in the leading industries (gold and coal mining, fishery), as well as due to rapid development of trade, there was an increase in the income generated and in the total number of jobs in the region by the beginning of the First World War. In 1900– 1913, the volume of industrial production in the Far East increased by almost 70%.

War economy. 1914–1922.

With the beginning of the First World War, the situation changed. State support was continuously decreasing and almost stopped since 1917. This led to a nearly complete decline of industry in the Far East, the industry which was to concentrate exclusively on the criteria of economic efficiency, from the point of view of which the region was far from leading

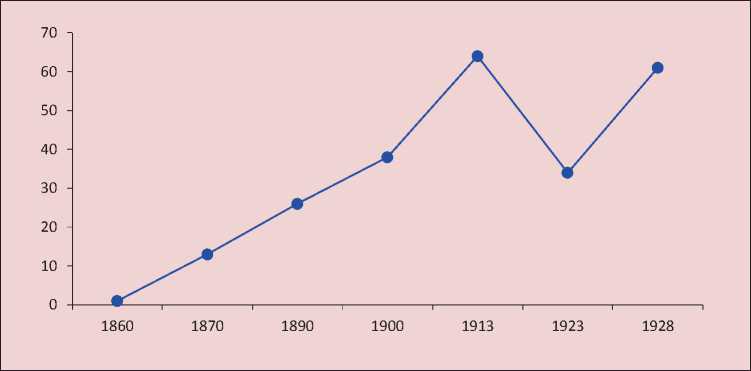

Figure 1. Changes in the volume of industrial production in the Far East, million rubles (in comparable prices as of 1926)

Source: Archival materials on the regional economic plan of the Far East (“Dal’kraiplan”). Khabarovsk. 1938. # 51. Sheet 2.

positions not only in Russia, but also in Siberia: it had the lowest concentration of production and, consequently, the lowest productivity [15, p. 140].

The scale of economic activities had to be matched with the changed conditions of functioning “on one’s own basis”. The gold industry found itself in a difficult situation. By the end of 1922, gold mining was only about 10% of the prewar level. Commercial production of tungsten, tin, and limestone stopped. The carrying capacity of the railways decreased more than fivefold.

The established economic relations of the Far East were almost completely disrupted, both within Russia and with Asian countries. The economic cycle was limited to the regional market. By 1922, industrial output in the region decreased by 47% in comparison with 1913 (Fig. 1) .

Due to the critical importance of external economic resources at that time, that period can be defined as “negative colonization”: the country invested its income in the region rather than sought to extract additional income from it. This can be interpreted as investments in future profits, but from the point of view of the region itself, it was the recipient of the country’s income.

Economic recovery (1923–1932).

The Center did not render any significant assistance to the Far Eastern region during that period. The region could rely only on its own resources. Regional planning and management authorities received broad powers, including the power to handle financial issues of capital construction and prospective development strategy. This helped concentrate resources in the most important and most promising areas (fish, forestry, gold mining) [16, p. 56]. In fact, in this period, a concept for planned management of the economy of the Far East was formulated which was implemented in the following 50 years. The essence of the concept consisted in concentrating limited resources in the sectors of specialization with simultaneous unconditional minimization of current and non-recurring costs in almost all the other economic sectors of the region [15, p. 144].

The concept was successful in the actual situation of the 1920s. In 1923–1928, the economy of the region received nearly one billion rubles of investments mainly from intraregional sources. Almost 15% of the total amount of investments was financed by a surplus of foreign trade, the cost of which was about 7% of the gross output of the region. The export quota reached 24% in the forest industry, 23.7% in the coal industry, and 7.4% in the fishing industry [16, p. 59].

By 1928, the economy of the Far Eastern Republic was largely rebuilt, new industries – petroleum and cement – emerged, and the gross industrial output of the Far East amounted to 95.3% from the level of 19133. While in general, the region’s economy remained predominantly agrarian. Only 9% of the population was employed in industry, and the value of agricultural products accounted for nearly 70% of the entire gross domestic product of the region.

Since 1928, the autonomation of economic life in the Far East gave way to integration into the national reproductive process. It was facilitated by changes in the national military and political priorities. Given the importance of the economic potential in terms of potential remoteness of the Far Eastern theater of military action from the European part of the USSR, a decision was made to accelerate the creation of economic potential that would be relatively autonomous in its main production elements in the Far East. Accordingly, the scale and source of resources for accumulation changed fundamentally.

As a result, in 1928–1932, additional investments allowed the volume of production in the heavy and extractive industries to be increased fourfold and the production of consumer goods – by 1.9%. Exports presented a significant share of total production: 24% – in the forest industry, 23.7% – in the coal industry, and 7.4% – in the fishing industry.

The Far East was turning from an agrarian into an industrial region.

Industrialization and the war economy. 1933–1945.

Since 1930, the economic barrier between the Far East and the “continental” Russia almost disappeared. Subsidies from the state budget compensated for increased transportation costs, costs of labor and energy. However, there emerged a political barrier on the eastern borders of the region, which led to a complete reorientation of the Far Eastern economy toward hinterland regions of the USSR. After 1933, centralized capital investment was pumped into the economy of the Far East. In 1933–1940, 10.2 billion rubles was invested in the economy of the region [20, p. 73]. The share of the Far East in the country’s capital investment rose from 0.8% in 1924–1927 to 6.3% in 1932–1937, and to 7.5% in 1938–1940. Only the Central and the Ural economic areas had the share exceeding that of the Far East [20, p. 73]. Over 100 industrial sites in Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk, Vladivostok, and Blagoveshchensk were built and renovated. The strongest gold and tin industries in the Soviet Union were created in the Magadan Oblast and in Yakutia [15, pp. 160-161].

By 1940, gross industrial output of the USSR increased in 8.5 times in comparison with 1913, and in the Far East – in more than 15 times. Coal production grew in 19.3 times, reaching 7.2 million tons by 1940 (in the whole Soviet Union, the growth was in 5.7 times), which allowed the country to abandon coal imports. Tree hauling in the region reached 15.8 million cubic meters by 1940, having increased in 4.6 times in comparison with 1928 and in 5.5 times in comparison with 1913 [15, p. 165]. By 1938, the Far East has turned into an industrial region, the share of agriculture in the total product of industry and agriculture fell from 68% in 1913 to 19.6% in 1937 [20, pp. 76-87].

Despite the war, the economy of the Far East continued to develop. By 1950, industrial output increased by 63% in comparison with 1940. The monotony of economic growth reflected the fundamental effect of centralization of resource allocation and the priority of non-profit and non-economic allocation criteria.

The Far East was not the main region to which the industrial potential of the USSR was evacuated during the war. However, several industrial enterprises from central regions of Russia and Ukraine were moved there. Industrial and infrastructure construction continued during the war; the region’s share in the capital investment in the 1940s was 7.8% of all capital investments of the USSR, which was higher than in the 1930s [3, p. 31].

The beginning of stagnation. 1946–1964.

The necessity of rebuilding the Soviet economy after the war demanded the concentration of all available resources in the Western regions of the country. The region’s share in the federal investment declined, and it was impossible to mobilize missing accumulation resources within the region at that stage, because the scale of the Far Eastern economy and the needed amount of investment increased dramatically. The Far East for a time lost its status of a priority region from the military-political point of view, which meant the need to engage in interregional competition for centralized accumulation resources. Such competition occurred on the basis of economic criteria, according to which the majority of economic sectors in the region lagged behind those in the Siberian and European regions.

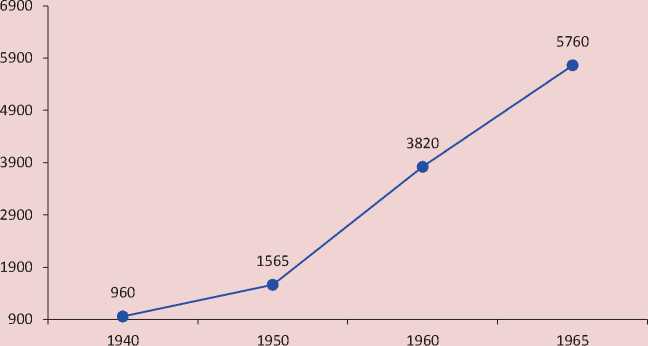

Due to the fact that fixed capital in the industries, the investment in which in the 1930s–1940s was carried out at an accelerated pace, was relatively new, and the high level of capacity utilization was widespread in the Soviet economy, the region’s economy was able to continue to grow rapidly (Fig. 2) , maintaining high average annual growth rates of its industrial production (9%).

But the pace of development in the Far East began to slow down and became lower than national average in the industry of the USSR (12.3% per year), which led to the Far Eastern dynamics lagging behind (in 1945–1964, the growth of industrial output in the Far East amounted to 600% vs 723% in the Soviet Union on the whole [13, p. 53]), which was contrary to the accepted regional development concept, involving the accelerated development of its economy.

An economic reform that was being prepared could reinforce the trend, since the reform envisaged a large-scale implementation of cost accounting principles in the allocation of resources, including the allocation of resources with regard to spatial planning, as well. It would pose a major challenge for the development of regional integration and subsidiary industries, for which the performance indicators limited the possibilities of development, given the narrowness of the domestic market. At the same time, the lag in the development of these industries could block the development of the entire economic complex.

Figure 2. Dynamics of gross industrial output in 1950–1965, million rubles (in comparable prices as of 1926)

Based on: [3, p. 31; 20, pp. 76-87].

Under the circumstances it became necessary to adjust the overall regional development concept through export-oriented production [17, pp. 3-15]. By the end of the 1950s, the focus on foreign trade was already quite evident. The volume of foreign trade turnover in the region increased in 15.5 times in comparison with 1938 [11, p. 13]. Since 1964, the concept received political interpretation. Long-term compensation agreements on the development of forest resources, coal, and natural gas were signed with Japan; according to the agreements these industries could obtain loans from Japan for fixed and working capital with the payment being made with finished products of these industries.

Five-year plans between the reforms. 1965– 1991.

Since the mid 1960s, there was another change in the economic situation in the Far East economy, which by this time was already rigidly connected to the national economic complex of the USSR.

First, the plans to increase the efficiency of production by implementing the principles of cost accounting in the assessment of enterprise performance did not and resource allocation system did not work out; and an extensive way of development became the defining strategy for the Soviet economy. It meant an increase in resource intensity of output growth and, therefore, an increase in the evaluations of the usefulness of the branches of specialization of the Far East to the national economy. The Far East started to attract the attention of the central government as a new source of raw materials for some industries.

Second, the military-political situation in the Far East became more acute once again, due to tense relations with China.

The circumstances led to the adoption of special decrees by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Council of Ministers of the USSR (1967, 1972); the decrees provided for the allocation of additional public investment to the development of the regional economy, construction of new industrial facilities, development of the raw materials base, energy, and defense industries. The share of the Far East in national investment began to increase and reached 7.1–7.4% in 1965–1975. Regarding the acceleration of growth rates this impulse did not have a significant positive effect (Tab. 1). The fact that the region’s growth rates were above national average was a small solace in the background of general decline in growth rates.

Growth rate was falling not only in industry in general, but in the industries that were most efficient and privileged from the viewpoint of obtaining resources in connection with the exhaustion of cheap sources of raw materials and slow introduction of new equipment and technologies. The lack of accumulation resources to provide for retired raw materials extraction capacities became even more pronounced.

In 1986–1987, an attempt was made to enhance the effect of using foreign markets for the region’s development. Mikhail Gorbachev declared the beginning of the turn of Soviet foreign and economic policy toward the Pacific region. A long-term state program for economic and social development of the Far Eastern economic region and the Transbaikal region for the period until 2000 was adopted in September 1987 and proclaimed a new era for the Far East.

From the very beginning, the proclaimed goal of creating an economic complex that would be competitive in the international market economy was at variance with the program provisions concerning the common tasks of system-wide integration of regional economy in national economy with the help of centralized capital investments. In 1986–1990, 51.5 billion rubles (7.6% of Russia’s aggregate national investments) was allocated to the Far East. It was quite comparable with the scale of investment in the development of the Far East in the period of industrialization. However, the program failed to change the inertia of the development. There existed neither the tools, nor ideology for an investment maneuver implemented for the purpose of upgrading the quality of the regional economy. The predominantly extensive development with limited resources led to further deceleration in growth, the increase in disparities reflect the system’s regional and national issues. However, it was structural problems that are not directly testified to, and did not anticipate the ensuing systemic crisis.

However, in 1987–1991, the economy of the Far East, being part of the national market and receiving government support, was gradually transformed into a marginal and relatively autonomous system with uncompetitive production, low export potential (including the export to domestic markets of other regions), and high dependence on imports. The transformation was actually completed in 1991 in the form of collapse of economic relations, which put the regional economy on the brink of disaster.

Table 1. Average annual growth rate of industrial production, %

|

1965-1970 |

1971-1975 |

1976-1980 |

1981-1985 |

1986-1990 |

|

|

USSR |

8.3 |

7.3 |

4.1 |

3.4 |

2.5 |

|

Far East |

8.3 |

7.0 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

2.8 |

|

Sources: Narodnoe khozyaistvo RSFSR v 1975 g . [Economy of the USSR in 1975]. Moscow, 1976; Ekonomiko-statisticheskii spravochnik DVER [Economic and statistics reference book of the Far Eastern economic region]. Khabarovsk – IEI DVO RAN, 1992. |

|||||

Transformational crisis and economic recovery. 1992–2007.

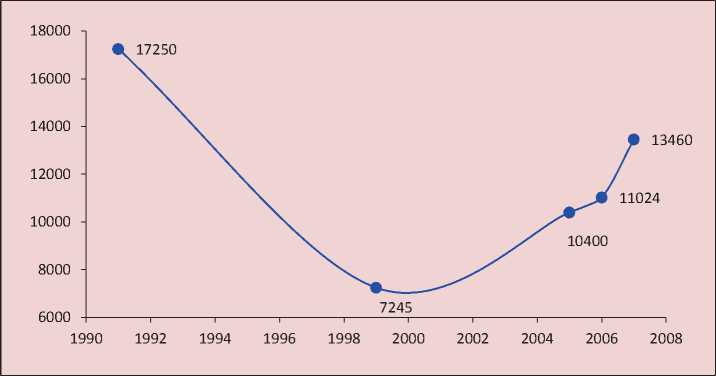

The transformation of the principle of “economic feasibility” as a criterion for interregional resource allocation and markets into the principle of interregional competition based on comparative parameters of production costs and investment expectations turned out to be devastating for the Far East of Russia, for which (see above) for almost 100 years, the allocation of resources had been based on non-economic criteria, and the only form of competition had been the competition for centralized “funds” (material, food, financial, etc.). In 1992–2007, the economy of the Far East went through a sharp downturn (1992– 1994) and depressive stabilization (1995– 1998) to economic recovery (1999–2007) (Fig. 3) . The Far East economy passed the lowest point in the crisis only in 1999. But the very period of transformational recession was not homogeneous.

Since the beginning of the reform there was no catastrophic collapse of the regional economy in terms of collapse of economic ties with the subsequent collapse of production and social systems. At the very beginning of the reforms (1992–1993), there were factors that supported the economy of the region.

First, the trend of priority development of the commodity sector, traditionally viewed as a negative trend, became positive under the new conditions, albeit for a short time. The raw materials sectors that defined industrial dynamics in the region, continued to receive state support for some time.

Secondly, the revenues from foreign trade that had been previously accumulated exclusively in the state budget started to come on the balance sheets of Far Eastern exporters, which compensated for the reduction in domestic demand and income.

These circumstances helped mitigate the manifestation of shock in the industrial

Figure 3. Dynamics of industrial production, million rubles, prices as of 1926

Sources: Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik: stat. sb. [Russian statistical yearbook: statistics collection]. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii, 1998. 813 p.; Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik: stat. sb. [Russian statistical yearbook: statistics collection]. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii, 2006. 750 p.

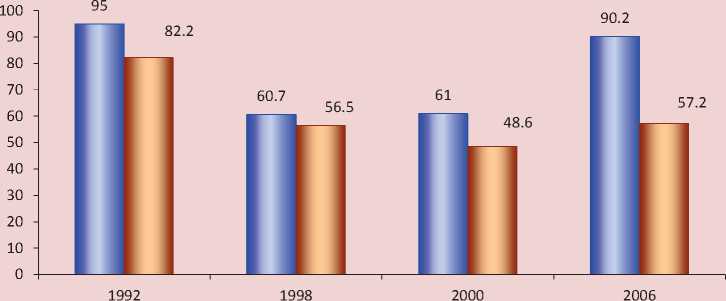

production in the region compared with the situation in Russia in 1992–1993 (25.2% against 29.5% in Russia on the whole in 1992– 1993); but in general, the regional economy was unable to replace the lost external (centralized) compensators with intra-regional or foreign economic ones, which resulted in a rapid formation of “dynamic scissors”, and in the region’s economy lagging behind national average (Fig. 4). In 1996, a “presidential” program for socio-economic development of the Far East until 2005 was adopted; it declared the restoration of state support for the development of the region at the expense of the federal budget, that is, the transition to a policy of maintaining cumulative economic growth. But the program could not amend the situation, and actual possibilities of the federal budget were greatly exaggerated. It became virtually impossible to overcome the transport and energy barriers and carry out structural modernization and major changes in the migration situation, even without the subsequent 1998 financial crisis, which actually annulled this program.

During the entire period after 1992, the region actually functioned in conditions of competitive interregional allocation of resources, which meant that the Far East would invariably lose, since its economic agents, as shown above, had no comparative economic advantages. Moreover, even the then level of state support for regions in reality resulted in a comparative loss of the Far East, because governmental policy was also based on the principles of comparative effectiveness of the spatial distribution of resources, which was obviously higher in regions possessing the initial economic advantage, and the Far East was not among them. As a result, state distribution only aggravated the relative economic depression of the region in full accordance with the concept of the so-called cumulative causation [27].

Figure 4. Dynamics of GDP/GRP, %, 1991=100

I п Russia □ Far East

Sources: Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik: stat. sb. [Russian statistical yearbook: statistics collection]. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii, 2006. 750 p.; Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik: stat. sb. [Russian statistical yearbook: statistics collection]. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii, 2008. 847 p.

In those conditions, economic growth in the region could only be predominantly endogenous in nature, based mainly on the accumulated inertia of the productive and social capacities created previously and on the income generated by export industries (forestry, mining, fishing, metallurgy).

By 1998, the region’s economic development reached its lowest point: the volume of gross regional product reduced by 44%; the volume of industrial production decreased by more than 50%; investment in fixed capital decreased by more than 70%.

Slow recovery of the regional economy began only in 1999 through the strengthening of the ruble after the devaluation following the 1998 crisis, and a stimulating role that export played in the Russian Far Eastern economy. The value of exports from the region in 1991– 2007 increased more than fivefold. Growing export incomes acted as a compensator for reducing interregional demand in the 1990s and as a factor in increasing the aggregate demand since 1999. It was largely facilitated by modernization of the “export core”, the group of specialization sectors that provided the bulk of regional exports. Since 2004, export deliveries of oil and gas from offshore fields of Sakhalin began, and by 2008, oil production has increased compared to 2000 in 3.6 times, and gas production increased in 2.7 times. It radically changed the structure of exports in the region. If in 1992, the export of oil and oil products was 4.1% of total exports, then in 2004, it was 33.6%, and in 2008 – 49.8% [13, p. 97].

It did not change the fact that the Far East had no support from the economic growth factors that were crucial for the Russian economy in that period; the factors included the rapid growth of income from hydrocarbon exports and the increase in domestic final demand as a result of aggregate income growth. The first factor emerged too late; besides, there was a very low level of localization of that part of income from exports, which remained after deduction of compensation under the agreement with the foreign investors of payments. The second factor was blocked by the fact that the region itself lacked the production and services of final consumption, which could perceive the impetus from the incomes.

However, in this period, favorable conditions began to be formed for the promotion of endogenous factors in economic growth due to the increased rate of investment in fixed assets mainly in two areas – investment in infrastructure in order to increase resource exports (sea ports, railways, motor roads, electricity, pipelines), and investment in the processing industry that was focused on export and national needs (oil and gas refining, machine building, wood processing, mining industry). The average annual growth rate of investment in fixed capital during this period amounted to more than 14%. In addition to some part of the investments allocated to the tertiary sector of the economy, most of them were allocated to the projects with relatively long term of development, which manifested in the statistical decrease in the marginal productivity of investment in fixed capital.

The financial and economic crisis of 2008– 2009 demonstrated the futility of hopes for the possibility to base macroeconomic dynamics in the Far East on endogenous factors. The cumulative impact of the shock of external demand due to the downturn of economies in Northeast Asia and the shock of domestic demand due to the reduction of federal budget revenues and decline in economic activity in the private sector led to the fact that in the first half of 2009, there was a nearly 18% decline in the region’s industry compared to the 11% reduction in Russia as a whole.

“The pivot to the East”. 2009–2017.

An increase in the assessment of “national economic value” of the Far East was due not so much to the crisis of 2008–2009, as to the deep geopolitical and macroeconomic problems emerging during its development, which required adjustments in national geo-economic policy in Russia. It was associated with the fact that already by 2007 there was an aggravation of the challenge of maintaining the possibilities of extensive growth of export rent in European markets, which was and remains the main source of comprehensive income and the main factor in economic growth of the national economy. Tough market competition, encouraged by restrictive regulation on European energy markets, increasingly interfered with the maintenance of stable positions in European markets. As for the increase in the share of intensive drivers of growth in foreign trade rent, it is impeded by the technological dependence of Russian export companies and a slow structural modernization of the economy that prevents from quick and efficient replacement of traditional export with its new types.

In addition, a model of the Russian economy established by 2009 assumed that in order to maintain the stability not only of growth, but also of the entire system of socioeconomic functioning it is necessary to ensure not only a certain level of extraction of export rent, but its increase, as well. It was objectively possible in short term only if the spatial field of extraction of export rent was expanded, while its product structure was maintained.

East Asia and, in particular, China were considered as a new and promising space for export expansion, especially in the energy sector. The implementation of the concept of “spatial re-branding”, of course, implied a substantial strengthening of infrastructure of the Far East as a transit ground for the country’s exports to new markets. The markets of East Asia, which traditionally served as the main compensator of fluctuations in domestic demand for the stabilization and development of economy of the Far East, now had to be turned into one of the main sources of growth and development for the national economy as a whole.

By 2009, much was made in the course of solving the most pressing infrastructure issues. New electricity generation capacities were commissioned, grid infrastructure was enhanced, the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Baikal–Amur Mainline were upgraded, tariff policy on railway transport was adjusted, seaports were renovated and developed; all this significantly improved the condition of the transport infrastructure [14]. In 2009– 2011, the priority development of major export infrastructure was continued. The region received considerable investment resources. The volume of gross investments amounted to 2.5 trillion rubles or 9% of fixed capital investment for Russia as a whole, which was comparable in proportion to the period of the 1970s, when the region modernized and expanded the military-industrial complex of national importance.

This time, investment boom was associated with the establishment of a reliable transport and energy infrastructure aimed at overcoming the existing restrictions on the intensive exploitation of existing deposits of mineral raw materials, fuel and energy resources of the region and the development of new ones; it was also aimed at increasing export deliveries to

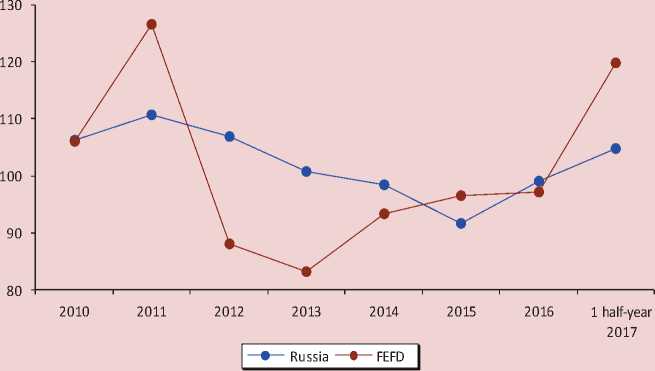

Figure 5. Investments in fixed capital, percentage of the previous period

Sources: Regiony Rossii. Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskie pokazateli. 2016 [Regions of Russia. Socio-economic indicators. 2016]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2016. 1326 p.; Information for monitoring the socio-economic situation in constituent entities of the Russian Federation. Federal State Statistics Service. 2017. Available at: rosstat/ru/statistics/publications/catalog/doc_1246601078438

the countries of the Asia-Pacific region. The most important projects of this kind included the Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean oil pipeline, resource projects in Southern Yakutia, the facilities of the APEC Summit in Vladivostok, regional pipelines, a network of federal highways, and modernization of sea ports [19].

Institutional maneuver

The construction of major corporate projects in the Far East (those directly related to the APEC Summit and those that implement a long-term export strategy) has been completed or was close to being completed by 2012. This led to a decline in investment activity in the region (Fig. 5). There remained high investment risks for private capital; it was reflected in a relatively higher index of investment risk in the region in comparison with national average4.

The federal budget, of course, could not compensate for the outflow of private capital.

But even if it were possible, it is unlikely that the result would be a significant change in the comparative macroeconomic dynamics in the region and in Russia as a whole, which does not depend much on the dynamics of investments in the economy of the Far East due to the above-mentioned specifics of the sectoral structure of investments leading to a long payback period and a low level of localization of the demand generated by investment. The actual investment dynamics have little effect on the pace of development of the region (Tab. 2) .

If the strategy of “investment pump” is inefficient from the point of view of achieving a dramatic change in the macroeconomic trends of the region, then the situation is different in the formation of standards of economic development of the region, i.e. dramatically improving the quality of life and

Table 2. Comparative growth rates of macroeconomic indicators, 2009–2016, %, 2009=100

Indicators Russia Far East Gross regional product 116.3 114.5 Industrial production 116.4 136.1 Export 91.3 157.4 Investments in fixed capital 113.4 86.2 People’s real incomes 106.9 112.2 Sources: Regiony Rossii. Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskie pokazateli. 2016 [Regions of Russia. Socio-economic indicators. 2016]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2016. 1326 p.; Information for monitoring the socio-economic situation in constituent entities of the Russian Federation. Federal State Statistics Service. 2017. Available at: doc_1246601078438

the business environment in the region. Without achieving this result, it is impossible to expect any stable integration of Russia in general and the Far East in particular in the economic system of East and Northeast Asia, even the state of the export infrastructure is satisfactory. For this sub-region of the world, the level of economic development and the institutional environment of potential partners are, if not decisive, then one of the most important conditions not just for trade interactions, but for full-fledged integration that is the ultimate goal of Russia in the East.

Therefore, it is necessary to solve the problem by promoting development rather than growth; that is, to change the quality of the social, utilities and business environments in the region, create incentives for intraregional income generation, achieve a fundamental change in the ratio of alternative costs to people’s incomes with the help of boosting business in general and investing in particular, since it will help solve the problem of outflow of the population and improve its quality more efficiently than all kinds of programs and benefits. This implies changing the structure of investment flows, which, given the absolute value, should be aimed at addressing the above tasks and supporting them with the help of institutional innovations.

Consequently, the most important condition of sustainable and effective development of the Far East, confirmed by the entire history of formation and modification of macroeconomic and social trends, is to preserve public investment of the measures aimed to address the issues of social and infrastructural development of the region in establishing an effective institutional environment promoting the activation of endogenous drivers of regional economic growth.

Aggravation of the macroeconomic and budget situation, along with awareness of the above-mentioned fundamental problems that have prevented success in the development of the region, has led to a change in the state policy for stimulating the development of the Eastern regions since 2013.

In the framework of a new state program for development of the region (2013–2018), the Eastern policy started to emerge as two relatively independent, although related, fragments. First, it was assistance, including financial assistance at the expense of the federal budget, to the development of the export infrastructure for extending foreign trade of Russian exporters in the eastern direction. Second, it was the implantation of institutional innovations [7; 10] aimed to raise private investments, including foreign ones, in order to increase the degree of endogeneity of economic growth in the region.

Obviously, these changes do not take into account to the fullest extent the trends in economic development of the region described above. The main issue is to preserve the interconnection between economic growth and socio-economic development, which is manifested in the interpretation of private investment as a tool to substitute public investment to support economic growth, especially in the export-manufacturing sector. Meanwhile, the priority tasks of economic development consist in the transformation of the Far East into a prosperous and modern region by improving human capital, community environment, and social infrastructure, and by creating comfortable business environment. The solution to these problems is possible only with the help of public-private partnership of the national level, in which public investment is focused on infrastructure and institutional framework of regional socioeconomic partnership, and private investment is concentrated in the sphere of maximizing export rent on the basis of exploitation of efficient natural and economic resources in the region and in the interregional system of national economy.

Conclusion

The study of the interdependence of macroeconomic trends and institutional environment for development of the Far East shows that there is no unambiguous solution to the problem of designing the “best” correlation between the objectives and means of regional development. This correlation was different for various historical stages, depending on the nature of the objectives pursued and the choice of tools for achieving them. However, it is possible with a certain degree of generality to formulate conditionally optimal relations between the goals of development and the types of economic policy in the region.

The best results were achieved when noneconomic goals of the state, for the achievement of which the region used centralized state material and financial resources, were combined with the goals of generating intraregional economic and financial resources, which was based on the support provided by government to the institutional environment that was as convenient as possible for the formation of endogenous reproduction within the region.

Accordingly, the periods when the state pursued exclusively “colonial” goals of extracting the maximum possible utility in the region with minimal support at the expense of state resources of endogenous development factors were the least successful from the point of view of maintaining stable socio-economic dynamics in the region.

Relative success was achieved with the use of a combination of building a preferential institutional regime that helps enhance the endogenous growth and development factors in the region, but that is not supported by the economic and financial resources of the state. In this case, positive economic and social development of the region is possible, but the influence of the state on the rate of this development and its feedback influence on the solution to public issues become minimal.

The modern period is characterized by a combination of “colonial” exploitation of transit and natural resource potential of the region, on the one hand, and on the other hand, by the substitution of economic and financial resources of the state with the institutional incentives in the sphere of designing an endogenous socio-economic system of the region. Such an eclectic combination of the approaches and purposes of application of economic and institutional resources will most likely result in a failure to implement the goals of neither the federal nor the regional level. We can assume that in the future it will be necessary to construct a new institutional economic framework for solving the dual problem of socio-economic development and national economic integration with East Asia.

Список литературы Centralization and autonomation as the drivers of socio-economic development of the Russian Far East

- Antologiya ekonomicheskoi mysli na Dal'nem Vostoke. -Vypusk 2. Issledovanie sel'skoi ekonomiki Priamurskogo kraya mezhdu russko-yaponskoi i pervoi mirovoi . Executive editor P.A. Minakir. Khabarovsk: RIOTIP, 2009. 288 p..

- Bol'bukh A.V., Zibarev V.A., Krushanov A.I., Kuznetsov M.S., Mandrik A.T., Flerov V.S. Istoriya Dal'nego Vostoka SSSR. Kn. 7 . Vladivostok, 1977. 250 p..

- Gladyshev A.N., Nikolaev N.I., Singur N.M., Shapalin B.F. Ekonomika Dal'nego Vostoka. Problemy i perspektivy . Khabarovsk: Khabarovskoe knizhnoe izdatel'stvo, 1971. 406 p..

- Dal'nii Vostok i Zabaikal'e v Rossii i ATR . Khabarovsk: IEI DVO RAN, 2005. 79 p..

- Granberg A.G. et al. Dvizhenie regionov Rossii k innovatsionnoi ekonomike . Moscow: Nauka, 2006. 400 p..

- D'yakonov F.F. Formirovanie narodnokhozyaistvennogo kompleksa Dal'nego Vostoka . Moscow: Nauka, 1990. 94 p..

- Isaev A.G. Territorii operezhayushchego razvitiya: novyi instrument regional'noi EKOnomicheskoi politiki . EKO, 2017, no. 4 (514), pp. 61-77..

- Kolosovskii N.N. Voprosy ekonomicheskogo raionirovaniya . Ekonomicheskoe raionirovanie SSSR . Moscow: GIGL, 1959. Pp. 6-14..

- Krushanov A.I., Kulakova I.F., Morozov B.N., Sem Yu.A. Istoriya Dal'nego Vostoka SSSR. Kn. 5. . Vladivostok, 1977. 305 p..

- Leonov S.N. Instrumenty realizatsii gosudarstvennoi regional'noi politiki v otnoshenii Dal'nego Vostoka Rossii . Prostranstvennaya ekonomika , 2017, no. 2 (50), pp. 41-67..

- Margolin A.B. Problemy narodnogo khozyaistva Dal'nego Vostoka . Moscow: Izd-vo AN SSSR, 1963. 255 p..

- Melamed I.I., Prokop'eva M.S. Vostochnaya politika Rossii i razvitie vostochnykh territorii RF . Regional'naya ekonomika: teoriya i praktika , 2013, no. 43 (322), pp.17-25..

- Minakir P.A., Prokapalo O.M. Regional'naya ekonomicheskaya dinamika. Dal'nii Vostok . Khabarovsk: DVO RAN, 2010. 304 p..

- Minakir P.A., Prokapalo O.M. Rossiiskii Dal'nii Vostok: EKOnomicheskie fobii i geopoliticheskie ambitsii . EKO, 2017, no. 4, pp. 5-26..

- Minakir P.A. Ekonomika regionov. Dal'nii Vostok . Moscow: Ekonomika, 2006. 962 p..

- Minakir P.A. Ekonomicheskoe razvitie regiona: programmnyi podkhod . Moscow: Nauka, 1983. 224 p..

- Nemchinov V.S. Teoreticheskie voprosy ratsional'nogo razmeshcheniya proizvoditel'nykh sil . Voprosy ekonomiki , 1961, no. 6, pp. 3-15..

- Priamur'e: fakty, tsifry, nablyudeniya . Moscow, 1909. 940 p..

- Prokapalo O.M., Isaev A.G., Suslov D.V., Devaeva E.I., Kotova T.N. Ekonomicheskaya kon"yunktura v DFO v 2011 g. . Prostranstvennaya ekonomika , 2012, no. 2, pp. 89-127..

- Tarasova Yu.A. Nekotorye itogi sotsialisticheskoi industrializatsii Dal'nego Vostoka za gody dovoennykh pyatiletok . Voprosy ekonomiki Dal'nego Vostoka . Blagoveshchensk: Amurskoe knizhnoe izdatel'stvo, 1958. Vol. 1. Pp. 71-97..

- Shlyk N.L. Vneshneekonomicheskie svyazi na Dal'nem Vostoke . Moscow: Sov. Rossiya, 1989. 149 p..

- Ekonomika Dal'nego Vostoka: perekhodnyi period . Khabarovsk; Vladivostok: Dal'nauka, 1995. 239 p..

- Ekonomika Dal'nego Vostoka: pyat' let reform . Khabarovsk: DVO RAN. 1997. 263 p..

- Ekonomika Dal'nego Vostoka: reforma i krizis . Khabarovsk; Vladivostok: Dal'nauka, 1994. 200 p..

- Ekonomicheskaya reforma na Dal'nem Vostoke: rezul'taty, problemy, kontseptsiya razvitiya . Khabarovsk, 1993. Pp. 46-50..

- Davis S.F. The Russian Far East: the Last Frontier? Routledge. London and New York, 2003. 176 p.

- Nijkamp P. (Ed.). Handbook of regional and urban economics. Free University. Amsterdam, 1986. 85 р.

- Lynn N.J. Resource Based Development: What Chance for the Russian Far East? The Russian Far East and Pacific Asia. Unfulfilled Potential. Ed. by M.J. Bradshaw. Routledge. London and New York, 2012. Pp. 10-31.

- Stephan J.J. The Russian Far East. A History. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 1994. 241 р.

- The Russian Far East and Pacific Asia. Unfulfilled Potential. Ed. by M.J. Bradshaw. Routledge. London and New York, 2012.