Classification of non-political participation practices of urban youth: forms, motivation, barriers

Автор: Antonova Natalya L., Abramova Sofya B., Gurarii Anna D.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.15, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article explores civic (non-political) participation practices among young people, which are understood as voluntary, public, and altruistic individual or collective actions. They are viewed as a condition for allowing young people to exercise their right to the city and are aimed at transforming urban space. The role of citizens in modern urban centres is increasing; they are becoming not only users, but also co-authors. Local activities that transform the territory in which young people live lead to an increase in their self-esteem and confidence, the acquisition of soft skills, and the formation of norms of interpersonal interaction. This study's main aim is to identify types of youth civic participation in a large industrial city. Drawing on data from an online survey (quota sampling, n = 800) of young people in the large industrial city of Yekaterinburg (Russia) conducted at the end of 2020, we suggest a typology of civic participation practices. The types were identified through the experience of participation in activities aimed at exercising a right to the city, a willingness to collaborate with other people, the degree of the institutionalisation of civic practices, and motivation to participate or not participate in civic practices. The article argues for building a constructive dialogue with government authorities to meet the needs of young people in transforming urban space. Studying specific do-it-yourself urban design practices in different cities and territories to find the most successful models for potential replication may be a promising direction for further research.

City, right to the city, civic participation, urban youth

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147237314

IDR: 147237314 | УДК: 316.62

Текст научной статьи Classification of non-political participation practices of urban youth: forms, motivation, barriers

Over recent decades, the relevant research literature has focused on a wide range of issues, including urban youth participation. Young people are viewed as engineers of the future. Their engagement in the city’s agenda and participation in urban life are considered prerequisites for developing urban space (Pancer et al., 2002). The importance of young voices being heard has been stressed. As actors in civic participation, young citizens are a fundamental resource in the intellectual and innovative development of a region. Their unique “mission” is to pioneer social transformation. Based on the analysis of sociological sources (Lisovskiy, 2000; Gribanova, 2012; Trotsuk, Sokhadze, 2014; Shchemeleva, 2019), civic participation is seen as a social quality of an individual, their activities aimed at transforming the environment and changing the personality itself.

The French researcher Michel de Certeau notes that, as a rule, citizen initiatives and practices are not included in urban planning and management strategies (Certeau, 1990). However, urban communities often act as a source and driving force in civic participation and attracting additional resources. Young citizens form groups, create movements, and mobilize resources to promote their ideas and projects for improving urban space.

Participation in city development gives individuals an opportunity to immerse themselves in activities that connect them with the world, which carries both individual and social significance (Nakamura, 2002). Local activities that seek to transform the territory in which young people live lead to an increase in their self-esteem and confidence, the acquisition of soft skills, and the formation of norms of interpersonal interaction.

Such activities may also increase civic competence through cooperation and discussion of key challenges and participation in public hearings. These actions enable young people to promote their interests within democratic principles (Youniss et al., 2002, р. 121).

The intensification of interactions between youth and local government, the development of dialogue with the representatives of government agencies, and the improvement of communication channels and management procedures in urban space development are conditions for making a city attractive to young proactive people who strive to change the city with their participation practices.

As such, the degree of a local government’s openness to grassroots initiatives may become a critical issue. As noted by N. David and A. Buchanan (David, Buchanan, 2020, р. 9), the institutionalization of youth participation in local governance and the prioritization of such participation in city planning strategies are still low. Similarly, R. Saito (Saito, 2006, р. 69) found that young people face various barriers, including access to information resources. Other researchers emphasize a gap in civic participation between people with different socio-economic statuses (Schlozman et al., 1999). Thus, the social segregation of urban space may decrease the number of local youth initiatives. Today’s youth strive to take leadership roles and participate in the life of their cities and communities, but they do not always succeed in implementing their initiatives (Mclaughlin, 2019) or fully exercising their right to the city (Lefebvre, 1996).

When transforming the city to realize their life plans and intentions, young people also themselves change, acquiring new social characteristics, roles, and statuses. Changing the city and changing themselves, young people gain social experience through learning norms and values, thus reaching social maturity.

Theoretical framework

Civic participation in the functioning, development, and management of cities is the focus of numerous discussions in the research literature (Lefebvre, 1991; Purcell, 2002; Harvey, 2008; Soja, 2010). The actions of an urban population are determined by their needs and ideas about the image of the city in which they want to live, study, work, and spend their free time. Civic participation practices are becoming an essential part of urban life (Sedova, 2014; Faehnle et al., 2017). The role of citizens in modern urban centers is increasing; they are not only users, but also co-authors. Civic participation in spatial transformations results in qualitative changes in the individual: increasing their emotional attachment to a city, the affirmation of territorial identity, and developing responsibility (Antonova et al., 2020, p. 389). Therefore, the city becomes a valuable resource for its residents.

Currently, there is a wide range of civic participation practices. We define them as voluntary, public, altruistic, and non-political individual or collective social actions. They are viewed as a condition for allowing young people to exercise their right to the city and are aimed at transforming urban space. Among the new types of civic participation, one can find do-it-yourself urban design (Gordon, 2014), ‘guerrilla’ urbanism (Finn, 2014), bicycle activism (Balkmar, Summerton, 2017), community gardening (Rogge, Theesfeld, 2018), and others. The performers of urban initiatives are described as “informal actors” (Groth, Corijn, 2014, р. 204), or, in emergency cases, “spontaneous volunteers” (Twigg, Mosel, 2017, р. 445). It is hardly possible to provide a complete taxonomy of such activities. Some are unique and isolated, others have been reproduced in different places, and some are incomplete and open. These initiatives can be constructive or destructive, rational or irrational, situational (temporary) or permanent (sustainable). Thus, O. Zhuravlev (Zhuravlev, 2017, р. 129) emphasizes time as a decisive factor in the classification of such initiatives.

Practices of local civic participation act as an expression of a civic position and reflect a civic strategy of participation in the production of urban space. As M.N. Koroleva and M.A. Chernova note, “the local civic activism is the result of a conscious choice, a kind of civic strategy” (Koroleva, Chernova, 2018, p. 94). The government ignoring the needs of citizens and the “invasion” of territory “appropriated” by residents (courtyard, house, borough) are drivers for collaboration between citizens. Such associations represent the interests of citizens and strive to address local urban problems. Based on neighborhoods, the purpose of public initiative associations is to comanage the area of residence (Evans, 2002). As Western researchers note, a friendly neighborhood as a formed communication system determines the manifestation of proactive practices: from gifts to joint social activities, which contributes to an increase in life satisfaction (Crean, 2012; Browning, Soller, 2014).

Petitions and appeals to local government, media campaigns, protests, online discussions, and mobilization are examples of traditional civic participation practices in urban development (Fisher et al., 2012, р. 28).

The existing research demonstrates that young people are the most active actors in civic participation, making a significant contribution to the city’s social capital (Ginwright, Cammarota, 2007; Gallay et al., 2020). As A.A. Zhelnina (Zhelnina, 2015, p. 47) notes, Russian cities are characterized by the “intervention” of creative urban youth in improving and transforming space. Young people adapt changing realities to their needs (Zubok, Chuprov, 2019, p. 181). The city becomes a platform for self-realization and self-expression, a stage for the manifestation of youth actions (Jacobs, 1961). The participation of youth in the production of city space helps them exercise their right to the city and strengthens their agency.

Our empirical and sociological research is focused on building a typology of the practices of youth civic participation. Reviewing the works that attempt to design such a typology, we did not find any typologies substantiated by empirical data. At the same time, we should recognize that some works contain interesting ideas and provisions concerning urban residents’ political participation: researchers focus on institutional and non-institutional political actions (Hooghe, Marien, 2013), individual and collective participation (Ekman, Amna, 2012), as well as offline and online practices of political activity (Oser et al., 2013; Dombrovskaya, 2020).

The project of the Center for Civic Analysis and Independent Research/GRANI (Perm) is among the studies focused on typology of civic participation (Demakova et al., 2014). The researchers have proposed an extensive list of civic participation practices reflecting current initiatives aimed at improving the lives of different social groups: protection of public spaces, local history and urban protection, protection of interest of people with special needs etc. A.A. Beksheneva and N.N. Yagodka proposed a typology of civic associations (Beksheneva, Yagodka, 2020). G. Badescu and K. Neller analyzed the reasons for civic participation that contributes to increasing trust in society and becomes a tool for inclusion in political life (Badescu, Neller, 2007). S.M.

Moskaleva and E.V. Tykanova analyzed the realization of non-governmental organizations’ projects aimed at improving the urban environment in Saint Petersburg and divided them into following trajectories: delayed trajectory, fragmentation trajectory, partial implementation trajectory and initial projects’ transformation trajectory (Moskaleva, Tykanova, 2016, p. 118).

In general, the research analysis of typologies of citizen participation (social, political, civic) is focused on determining the types of initiatives and drivers of their inclusion in organizations that are actors in various kinds of innovations and transformations (Van der Meer et al., 2009; Suter, Gmur, 2018), while the basis is the coincidence of the values of the participants with the values of the organization (Clary, Snyder, 1999).

The issue regarding the typology of youth civic participation has not been in the focus of sociological community yet. The proposed research will contribute to deepening and expanding the understanding of civic participation of urban youth on the basis of a typology built on the empirical data.

Methods

This empirical sociological research was conducted at the end of 2020. The focus was the youth of the city of Yekaterinburg.

Yekaterinburg is the fourth largest Russian industrial city in terms of population. On the one hand, it is a regional city, remote from the historical capitals (Moscow and Saint Petersburg). On the other, it is one of the fastest growing urban centers in the country and the largest in the Urals. The city has hosted several significant events, including international industrial exhibitions and the 2018 FIFA World Cup. Young people aged 18–30 make up 15.1% of the population, with 9% currently studying in various educational institutions. In comparison, in Russia as a whole, students make up 2.85% of the population. Yekaterinburg can be described as a youth city: this is due not only to the large number of educational institutions, but also numerous opportunities for an engaging life beyond formal education. The city strives to be a cultural, historical, creative, entertainment, political, and sports center. In this sense, Yekaterinburg provides a developed environment for the manifestation of youth activities and is open to different kinds of initiatives.

The study’s main aim is to identify the motives and factors that determine civic participation among young citizens and, as a result, build a typology of youth civic participation in a large industrial city. The research goals are the following: to consider the nature of youth civic participation (individual/group); to reveal the organizational level of youth civic participation; to characterize the motivation of young citizens for civic participation; to reveal the reasons why young citizens choose not to participate in civic practices.

The data analyzed in this article was obtained by a formal online survey (quota sampling). It consisted of 25 questions (17 closed-ended questions, 4 open-ended questions, and 4 semiclosed questions). The survey was open from November 3 to December 31, 2020, and was distributed through social media, educational institutions’ websites, city information platforms, urban communities, and other channels.

By the end of the survey period, 837 responses had been collected, of which 37 were rejected according to the following criteria: age discrepancy, city of residence discrepancy, low level of survey completion (a large number of missed questions, the prevalence of the answer “I find it difficult to answer”), and compliance with quotas based on gender, age, and employment. The final sample included the responses of 800 participants aged 18 to 30; of them, 60% were girls and 40% boys. The distribution of respondents by age is as follows: up to 22 years old – 55.6%, 23–26 years old – 27.8%, over 27 years old – 16.6%. Student youth make up 50.3%, working youth 43.6%, not working and not studying 6.1%. Every fifth participant was married; 35% of respondents identified themselves as middle class. The average time taken to complete the survey was 20 minutes. The data was analyzed using SPSS and subjected to frequency, crosstabulation, and correlation analysis to calculate a percentage, average indicators, and correlation coefficients.

Since young people from only one city were included in the sample, our findings are not intended to be representative and cannot be generalized to the level of all Russian youth. Similarly, they may not completely coincide with previous research on youth activity in different types of cities or in cities with different levels of socio-economic development. At the same time, we believe that for Russian cities with a millionplus population the types of civic participation of the younger generation may be similar. According to the Federal State Statistics Service, there are 15 million-plus cities including Moscow and Saint Petersburg in Russia, as of January 1, 20211.

Results and discussion

A typology for youth civic participation activities can be developed in various ways. In this article, we consider three typologies based on the fundamentals of social action: the individual or group nature of activities, the organizational level of activities, and the motives underlying participation and nonparticipation.

Typology 1

We used two criteria to classify youth groups in terms of the collective forms of activities: the experience of participation in activities for exercising their right to the city and the willingness to collaborate with other people in joint actions aimed at improving city life and developing urban space. At the intersection of these criteria, four distinct groups of young people were constructed.

-

1. Active collaborators (41.5% of the respondents) have experience of participating in developing urban space and express willingness for collective action and cooperation with other people. This group includes a slightly higher share of men, more people aged 27–30, and those who are married and have children.

-

2. Active individualists (7%) regularly participate in city public life but still prefer individual activities.

-

3. The collaborative pool (30%) has not yet joined in activities for developing their city but is potentially ready to cooperate with other residents.

-

4. Anti-activists (21.5%) have not participated and are not ready to engage in cooperation.

We have not found any pronounced differences between the socio-demographic characteristics of all these groups. Young people with absolutely identical gender, age, income, and education attributes can belong to any of the four groups. However, they differ significantly in their assessment of the role of residents in urban development. Thus, among the first type (active collaborators), 55% feel responsible for what is happening in their city and 71% – in their apartment building. Among the fourth type (antiactivists), 14% and 37%, respectively, share such a sense of responsibility.

It is also clear that the forms of civic participation are correlated with assessments of their

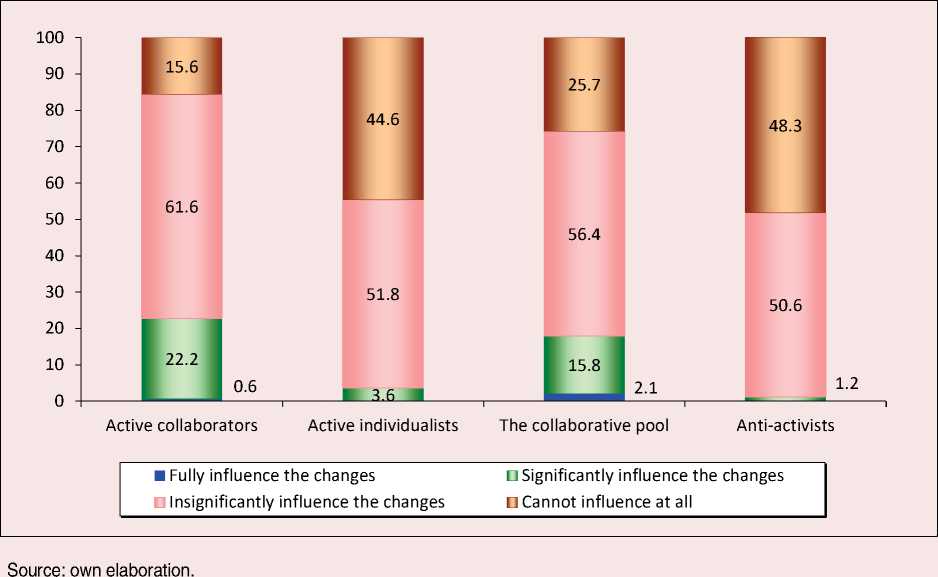

Figure 1. The degree of influence of different groups on city agenda, depending on the forms of activity (collective/individual), in %

effectiveness. Among those who chose collective forms, there are fewer people who consider such actions as incapable of influencing city life (16% among active collaborators, 25% among the collaborative pool, 45% among active individualists, and 48% among anti-activists; Fig. 1 ).

It is worth noting that although some respondents believe that residents’ activities are not very effective, they do participate in such activities or are ready to do so in the future. This indicates, first, the importance of such participation and an unwillingness to be inactive, and second, their belief in the ability to change through action the attitude toward this type of activity and the potential for increasing the importance of urban youth activism. Among the surveyed, 48% took part in some kind of activity to develop urban life over the past year.

Typology 2

The second typology reflects the models of participation depending on the organizational level of civic practices. We have constructed four models.

-

1. Fully institutionalized forms that originate from pre-existing instruments devised by federal and local government (33% of all cases of participation in urban activities). They include written appeals, through the internet as well (13%) and oral statements in public institutions on topical issues (10%), and participation in public hearings on the development of urban space (10%).

-

2. Forms of citizen self-organization that are based on mutual cooperation with federal and local government (54% of the used practices). To illustrate this, young people point out participation in agreed meetings (13%), cleaning and renovating

-

3. Fully self-organized (non-institutionalized) forms without engaging with city authorities, including within the framework of civil society institutions (73%). The most common option is participation in the activities of NGOs and nonprofit organizations (25%), gathering like-minded people to address the problems of the yard, house, or part of the house (8%), and participation in various kinds of meetings (23%). These forms also include unauthorized rallies, pickets, and protests that affect urban construction, transport, and other issues (17%).

-

4. Non-formal online activities taking place on the Internet: on social media, in blogs, and on city forums (46% of all participation activities over the past year).

courtyards, parks, and embankments (31%), helping the underserved population (10%), and others.

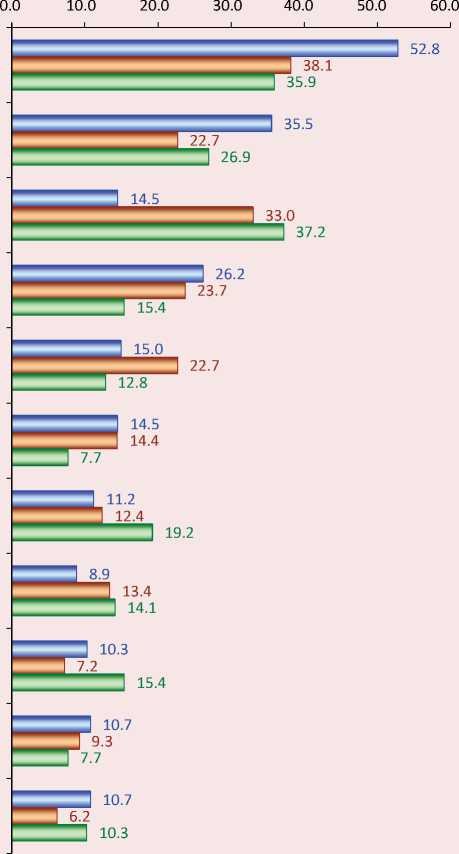

We should note that the structure of the above participation models changes with age and demonstrates a downward trend in online activity, as well as an upward trend in institutionalized practices and interest in addressing local issues (house/yard) (Fig. 2) .

Some respondents have experience of participating in only one type of activity. Thus, 7% participated only in cleaning and renovating the city environment, 5% only in meetings, and 12% only discussed urban problems online. According to K. Clement (Clement, 2015, р. 211), civic participation in Russia takes place through small practices and interactions. However, our research has shown that most young people combine various forms of civic participation, choosing on average three answers. Consequently, young people develop experience of participating in both situational and permanent practices. The preferred forms are non- formal offline activities, but there is also extensive cooperation with government agencies. These findings serve as a promising basis for increasing the level of trust between both parties and developing a wide range of urban residents’ participation practices aimed at implementing their right to the city.

Typology 3

The third typology of civic participation concerns the motivation of both participants and non-participants in activities to improve urban life and space. We identified five groups of motivation factors common to these two categories and one group of motivation factors specific to non-participants. Since the purpose of civic participation is to improve the lives of citizens, three main motivation factors directly affect three levels of such improvement: the world as a whole, the city environment, and the citizen personally (Table) .

The first group of motives reflects the idea of improving the world as such (47% of all reasons for participation) or helping people (16%). The city here is a venue for meeting these global needs.

The second group of motives addresses the need for a comfortable living environment, an urban identity, and love for the city: 58% of survey participants strive for their city to be beautiful, clean, and modern.

Personal development and the maximum use of one’s potential make up the third group of motives. On the one hand, self-interest is clearly involved when urban projects are considered a way of acquiring valuable contacts (7%), career advancement and gaining power (2%), and promoting one’s ideas (7%). On the other hand, young citizens strive to make full use of their free time for public benefit (13%) and develop their personal qualities (13%).

Figure 2. Forms of civic participation depending on the age of the respondents, in %*

Expressed their opinion on the Internet

Participated in activities for the improvement of public spaces

Participation in tenant meetings

Participation in NGOs, NPOs

Participation in protests on city development agenda

Participation in peaceful demonstrations on city development agenda

Appeals to the state authorities on city development agenda

Participation in discussions held in city administration

Helped citizens in difficult life situations

Participation in public hearings on city development agenda

Organized a team to solve some problems of the city

□ 18–22 □ 23–26 □ 27–30

* % calculated on number of people who engaged in civic activity over the last year for each age sub-group Source: own elaboration.

Typology of motives for participation and non-participation in urban activities, %*

|

MOTIVES FOR PARTICIPATION |

MOTIVES FOR NON-PARTICIPATION |

||

|

1. Saving the world and people |

|||

|

I want to help people |

16 |

Lack of faith in the possibility of positive change |

62 |

|

I want to change the world for the better |

47 |

||

|

2. Improving the living environment |

|||

|

I want to live in a clean city |

58 |

Lack of personal attachment to the city and city identity |

12 |

|

3. Personal and career development |

|||

|

I have free time that I want to use meaningfully |

13 |

Lack of knowledge about how to influence the situation |

51 |

|

I want to develop my skills |

13 |

It may take too much time, effort, and money |

33 |

|

I plan to make valuable contacts |

7 |

Indifference and laziness |

32 |

|

I want to spread my ideas |

7 |

It is not interesting |

15 |

|

I feel that I can develop personally in this area |

3 |

Lack of necessary connections |

9 |

|

I can move up the status ladder and gain access to resources and power |

2 |

Lack of necessary skills |

9 |

|

4. Alternative to government action |

|||

|

The local government is unable to transform the city |

34 |

Everything is decided by other people and the government |

28 |

|

I want to represent the interests of the urban community in city management |

6 |

||

|

5. Communication |

|||

|

I like to communicate with like-minded people |

4 |

One can’t do it alone; one needs like-minded people |

31 |

|

My friends have participated |

4 |

||

|

6. Fears |

|||

|

- |

Fear of sanctions that may follow |

40 |

|

|

It may be dangerous |

33 |

||

|

* % is calculated on the number of respondents to these questions. The amount is more than 100%, because each participant could name several reasons for participating/not participating in improving the urban environment. Source: own compilation according to the results of an online survey of Yekaterinburg youth. |

|||

Of particular interest here is the fourth type of the motives, which are based on replacing the unsuccessful efforts of local government with more effective actions to address urban problems. Thirty-four percent believe that residents engage in urban activism when they understand that the city authorities are unable to transform the city, while another 6% are ready to represent the interests of the city community in urban management. In the same vein, A. Arampatzi and W.J. Nicholls found that an inability or a weak ability of the city authorities to control and address urban problems is a reason for the emergence and development of social movements (Arampatzi, Nicholls, 2012, р. 2591).

The fifth group of the motives reflects young people’s critical need for communication: 8% consider collective forms of urban activism as an opportunity to spend time with friends and likeminded people.

Several distinct features have been observed in the structure of motives for non-participation in addressing urban problems. The role of motivation related to personal resources is significantly increasing. The study’s participants believe that non-participation in urban activities occurs due to a lack of required skills (9%), a lack of information on the specific ways one can influence the life of the city (51%), a lack of interest (15%), and indifference and/or laziness (32%). An additional anti-motive is the perceived significant expenditure of time, effort, and money (33%). In other words, the study’s participants perceive intrapersonal reasons, i.e. low willingness to regularly practice civic participation, as the main obstacle. The role of friends who can introduce others to urban activism is growing: 31% of the respondents believe that the absence of such like-minded mediators is a significant obstacle. The motive for improving the world has retained its high importance. Thus, a lack of confidence in the possibility of positive changes and effective actions hinders civic participation among 62% of the respondents. This idea is continued by those who believe that city residents do not engage in activism since they think that ordinary citizens have little power in public decision-making; so, when they are dissatisfied with the actions of the city authorities, they are not able to influence decisions (28%).

Finally, we would like to draw attention to a specific aspect associated with fears: 33% believe that people think carrying out public activities can be dangerous, while 40% associate activism with possible adverse outcomes. This points to significant aspects in understanding the very essence of civic participation. In our opinion, there is a blurred border with political activism, which is perceived predominantly as a protest movement and leads to confrontation with the official authorities (informationally, physically, and in other ways). Equally, ideas about participation are often built on associations with individual performance and a fanatical fight for ideas by those who “have nothing else to do”2. Hence, one of the fundamentally essential tasks for the successful development of civic participation is raising awareness about its purpose, tasks, and forms, which, among other things, will help to remove it from the category of antisocial actions subject to authorization by the government.

Conclusions

As a result of this empirical sociological research, we have identified the following types of civic youth participation. First, based on the criterion of experience of participation in activities aimed at exercising a right to the city and the willingness to collaborate with other people, we offer the following typology: active collaborators (41.5%), active individualists (7%), the collaborative pool (30%), and anti-activists (21.5%). Second, the typology based on the level of organization of civic practices consists of fully institutionalized forms that originate from pre-existing instruments devised by the federal and local government (33%), forms of citizen self-organization based on mutual cooperation with the federal and local government (54%), fully self-organized (non-institutionalized) forms without engaging with the city authorities including within the framework of civil society institutions (73%), and non-formal online activities such as social media, blogs, city forums (46%). Third, we suggest a typology of civic participation based on young people’s motivation to participate in such practices: improving the world (47%) and helping people (16%), the need for a comfortable and supportive living environment (58%), the need to communicate (8%), the need for personal development (13%), and constructive actions as a response to the inadequacy of government efforts (34%). Among the reasons not to participate in civic practices, a special place is occupied by the motives associated with perceived danger from participating in such activities (33%), as well as potential sanctions (40%). In general, we argue that it is important to strengthen the dialogue between authorities and young people exercising their right to the city: to increase the confidence level of young citizens in regional authorities by implementing effective ways of interaction in the course of implementation of specific projects. The presented typologies allow us to consider the phenomenon of civic participation of urban youth in different aspects and can be further used depending on the goals of theoretical, applied and empirical projects (for example, it is advisable to rely on typology 1 while creating new forms of youth participation in urban practices, and on typology 3 while creating a motivating video for youth participation).

The proposed study makes it possible to expand the modern understanding of the younger generation of a large city and its potential in civic participation. In line with the concept of the “right to the city”, civic participation acts as a source and driving force for the appropriation and transformation of urban space. The identified types of youth civic participation will undoubtedly contribute to theoretical sociology and will be of interest to specialists implementing regional youth policy, as well as to practicing managers whose activities are aimed at city development. Studying specific do-it-yourself urban design practices being implemented in other cities and territories in order to find the most successful models for potential replication may be a promising direction for further research.

Список литературы Classification of non-political participation practices of urban youth: forms, motivation, barriers

- Antonova N., Abramova S., Polyakova V. (2020). The right to the city: Daily practices of youth and participation in the production of urban space. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny=Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, 3, 384–403. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2020.3.1597 (in Russian).

- Arampatzi A., Nicholls W. (2012). The urban roots of anti-neoliberal social movements: The case of Athens, Greece. Environment and Planning, 44, 2591–2610. DOI: 10.1068/a44416.

- Badescu G., Neller K. (2007). Explaining associational involvement. In Van Deth J.W., Montero J.R., Westholm A. (Eds.). Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis. New York: Routledge.

- Balkmar D., Summerton J. (2017). Contested mobilities: Politics, strategies and visions in Swedish bicycle activism. Applied Mobilities, 2(2), 151–165. DOI: 10.1080/23800127.2017.1293910.

- Beksheneva A.A., Yagodka N.N. (2020). Political and non-political forms of citizen participation in public life in Russia. Vestnik Rossiiskogo universiteta druzhby narodov. Seriya: Gosudarstvennoe i munitsipal'noe upravlenie=RUDN Journal of Public Administration, 7(1), 25–35. DOI: 10.22363/2312-8313-2020-7-1-25-35 (in Russian).

- Browning C.R., Soller B. (2014). Moving beyond neighborhood: Activity spaces and ecological networks as contexts for youth development. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 16(1), 165–196.

- Certeau M. de (1990). L’invention du quotidien. 1. Arts de faire. Paris: Éditions Gallimard. Folio essays.

- Clary E.G., Snyder M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(5), 156–159. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8721.00037

- Clement K. (2015). Unlikely mobilisations: How ordinary Russian people become involved in collective action. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 2(3–4), 211–240.

- Crean H.F. (2012). Youth activity involvement, neighborhood adult support, individual decision making skills, and early adolescent delinquent

- behaviors: Testing a conceptual model. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 175–188. DOI: 10.1016/j.appdev.2012.04.003

- David N., Buchanan A. (2020). Planning our future: Institutionalizing youth participation in local government planning efforts. Planning. Theory & Practice, 21(1), 9–38. DOI: 10.1080/14649357.2019.1696981.

- Demakova K., Makovetskaya S., Skryakova E. (2014). Non-political activism in Russia. Pro et Contra, May–August, 148–163. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/ProEtContra_63_148-163.pdf (accessed: December 10, 2021; in Russian).

- Dombrovskaya A.Yu. (2020). Civil activism of youth in modern Russia: Features of its manifestation in online and offline environments. Vlast’=The Authority, 28(2), 51–58. DOI: 10.31171/vlast.v28i2.7134 (in Russian).

- Ekman J., Amna E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22(3), 283–300. DOI: 10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

- Evans P. (2002). Livable Cities? Urban Struggles for Livelihood and Sustainability. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Faehnle M., Mäenpää P., Blomberg J., Schulman H. (2017). Civic engagement 3:0 – Reconsidering the roles of citizens in city-making. The Finnish Journal of Urban Studies, 55(3). Available at: https://www.yss.fi/journal/civic-engagement-3-0-reconsidering-the-roles-of-citizens-in-city-making/ (accessed: April 25, 2021).

- Finn D. (2014). Introduction to the special issue on DIY Urbanism. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 7(4), 331–332. DOI: 10.1080/17549175.2014.959154

- Fisher D., Campbell L., Svendsen E. (2012). The organizational structure of urban environmental stewardship. Environmental Politics, 21(1), 26–48. DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2011.643367

- Gallay E., Pykett A., Smallwood M., Flanagan C. (2020). Urban youth preserving the environmental commons: Student learning in place-based stewardship education as citizen scientists. Sustain Earth, 3(3). 1–10. DOI: 10.1186/s42055-020-00026-1

- Ginwright Sh., Cammarota J. (2007). Youth activism in the urban community: Learning critical civic praxis within community organizations. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(6), 693–710. DOI: 10.1080/09518390701630833

- Gordon D. (2014). Do-it-yourself urban design: The social practice of informal “improvement” through unauthorized alteration. City & Community, 13(1), 5–25. DOI: 10.1111/cico.12029.

- Gribanova V. (2012). The essence of the concept “activity” in scientific literature. Vestnik Taganrogskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogicheskogo instituta. Seriya “Gumanitarnye nauki: pedagogika, psikhologiya, politologiya i sotsiologiya, ekonomika, pravo”. Spetsvypusk no. 1=Bulletin of the Taganrog State Pedagogical Institute. Ser. “Humanities: Pedagogy, Psychology, Political Science and Sociology, Economics, Law”. Special Issue, 1, 15–19 (in Russian).

- Harvey D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, 23–40.

- Hooghe M., Marien S. (2013). A comparative analysis of the relation between political trust and forms of political participation in Europe. European Societies, 15(1), 131–152. DOI: 10.1080/14616696.2012.692807

- Jacobs J. (1961). Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Koroleva M., Chernova M. (2018). Urban activism: Management practices of authorities as resources and barriers for urban development projects. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 9, 93–101. DOI: 10.31857/S013216250001963-2 (in Russian).

- Lefebvre H. (1991). The Production of Space. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Lefebvre H. (1996). Writings on Cities. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Lisovskiy V. (2000). Dukhovnyi mir i tsennostnye orientatsii molodezhi [Spiritual World and Value Orientations of the Youth of Russia]. Saint Petersburg: SPbGUP.

- Mclaughlin D. (2019). How young people are healing the world: An activist reflects on the Tikkun youth project. In: Daniel Y. (Ed). Tikkun Beyond Borders: Connecting Youth Voices, Leading Change. Available at: https://windsor.scholarsportal.info/omp/index.php/digital-press/catalog/view/156/291/1467-1 (accessed: May 1, 2021).

- Moskaleva S.M., Tykanova E.V. (2016). Social conditions of the performance of civic and expert groups aimed at the improvement of the quality of urban environment. Zhurnal sociologii i social'noj antropologii=Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, XIX(4)(87), 103–120 (in Russian).

- Nakamura L. (2002). Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet. New York: Routledge.

- Oser J., Hooghe M., Marien S. (2013). Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification. Political Research Quarterly, 66(1), 91–101. DOI: 10.1177/1065912912436695

- Pancer M., Rose-Krasnor L., Loisell L. (2002). Youth conference as a context for engagement. New Directions for Youth Development, 96, 47–64. DOI: 10.1002/yd.26

- Purcell M. (2002). Excavating Lefebvre: The right to the city and its urban politics of the inhabitant. GeoJournal. 58, 99–108.

- Rogge N., Theesfeld I. (2018). Categorizing urban commons: Community gardens in the Rhine-Ruhr agglomeration, Germany. International Journal of the Commons, 12(2), 251–274. DOI: 10.18352/ijc.854.

- Saito R. (2006). Beyond access and supply: Youth-led strategies to captivate young people’s interest in and demand for youth programs and opportunities. New Directions for Youth Development, 112, 57–74. DOI: 10.1002/yd.193

- Schlozman K., Verba S., Brady H. (1999). Civic participation and the equality problem. In: Skocpol T., Fiorina M. (Eds). Civic Engagement in American Democracy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press.

- Sedova N. (2014). Сivic activism in modern Russia: Forms, factors, and social base. Sotsiologicheskiy Zhurnal=Sociological Journal, 2, 48–71. DOI: 10.19181/socjour.2014.2.495 (in Russian).

- Shchemeleva I.I. (2019). Social activity of the student youth: Factor and cluster analysis. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 4, 133–141. DOI: 10.31857/S013216250004594-6 (in Russian).

- Soja E. (2010). Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Suter P., Gmür M. (2018). Volunteer engagement in housing co-operatives: Civil society “en miniature”. Voluntas, 29, 770–789. DOI: 10.1007/s11266-018-9959-0

- Trotsuk I.V., Sokhadze K.G. (2014). Social activity of the youth: Approaches to the assessment of forms, motives and factors in the contemporary Russian society. Vestnik RUDN. Seriya: Sotsiologiya=RUDN Journal of Sociology, 4, 58–74 (in Russian).

- Twigg J., Mosel I. (2017). Emergent groups and spontaneous volunteers in urban disaster response. Environment and Urbanization, 29(2), 443–458. DOI: 10.1177/0956247817721413

- Van der Meer T., Te Grotenhuis M., Scheepers P.L. (2009). Three types of voluntary associations in comparative perspective: The importance of studying associational involvement through a typology of associations in 21 European countries. Journal of Civil Society, 5(3), 227–241. DOI: 10.1080/17448680903351743

- Youniss J. et al. (2002). Youth civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(1), 121–148. DOI: 10.1111/1532-7795.00027

- Zhelnina A. (2015). Creativity in the city: Reinterpreting the public space. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsialnoy antropologii=Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 2(78), 45–59. Available at: https://publications.hse.ru/mirror/pubs/share/folder/c3b8jtgfb6/direct/157650662.pdf (accessed: October 25, 2021; in Russian).

- Zhuravlev O. (2017). Vad blev kvar av Bolotnajatorget? En nystart för den lokala aktivismen i Ryssland. Arkiv. Tidskrift för samhällsanalys, 7, 129–164. DOI: 10.13068/2000-6217.7.4.