Clothes make the woman: the beads fashion in the Sarmatian cemetery from Hunedoara Timisana

Автор: Barca V., Grumeza L.

Журнал: Краткие сообщения Института археологии @ksia-iaran

Статья в выпуске: 268, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article analyses the beads discovered in the Sarmatian cemetery from Hunedoara Timisana (Arad County, West Romania). Beads are the most numerous dress items in the graves at Hunedoara Timisana, a total of 1396 beads (beside other fragmentary pieces) being identified in the 14 analysed graves. Beads fulfilled various functionalities within the analysed graves: they were part of necklaces, belts, earrings or buttons, but most often were sewn onto female garments. The custom of embroidery-decorating garment hems with hundreds or even thousands of beads of various colours is recorded in the Sarmatian milieu of the Great Hungarian Plain as early as their settling of the area. The fashion peaks in the period after the Marcomannic wars, very likely influenced by the arrival in this area of new groups of Sarmatians by the end of the 2nd - early 3rd c. AD.

Beads, fashion, sarmatians, cemeteries, hunedoara timisana, provincial roman workshops, western plain of romania

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143180123

IDR: 143180123 | DOI: 10.25681/IARAS.0130-2620.268.19-31

Текст статьи Clothes make the woman: the beads fashion in the Sarmatian cemetery from Hunedoara Timisana

In the summer of 2010, the rescue archaeological excavations prior the construction of the Arad-Timişoara Highway, respectively the Arad-Seceani section, investigated several archaeological sites and features, among which also site B0_7-B0_8 , located within the range of Hunedoara Timișană village, Șagu commune (Arad county) ( Bârcă et al. , 2011; Bârcă , 2014. P. 12–14). The investigations yielded 1 7 inhumations to which add the pieces from a grave destroyed by the construction of an early medieval house. The discovered graves represent a small settlement-related cemetery whose nucleus lay west the highway route ( Bârcă , 2014. P. 14). The graves’ layout

-

1 This work was supported by a grant of the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research, CNCS – UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P1-1.1-TE-2019-0783, within PNCDI III.

indicates that eastward and westward, outside the investigated limits, there existed other graves as well. The excavations performed in the southern side of the excavated perimeter investigated features of the Sarmatian settlement dated to the 3rd–4th c. AD and a few features from the early medieval period ( Bârcă et al. , 2011; Bârcă , 2014. P. 14). Except for grave 3, all the other had a rectangular grave pit with rounded corners, while in 14 cases the deceased were buried with head northwards, north-northwestwards and north-north-eastwards ( Bârcă , 2014. P. 73, 80)2. The predominant northern orientation of the graves from Hunedoara Timișană confirms, beside other previous or more recent finds, the entry of certain Sarmatian groups (the Roxolani) in the Great Hungarian Plain in the period after the Marcomannic wars (Ibid. P. 82, 83, 141). Chronologically, the grave groups from Hunedoara Timișană date to the interval comprised between the end of the 2nd c. and the third quarter of the 3rd c. AD ( Bârcă , 2014; 2016. P. 253, 254).

The results of the archaeological research carried out at Hunedoara Timișană supply a multitude of data regarding the interaction of the Sarmatians with the Roman and Germanic worlds and represent, beside other recent finds, proof that the Sarmatians settled the territory south the Lower Mureș river after the Marcomannic wars. Also, it is very likely that the deceased buried with the head northwards from cemeteries on the territory of Banat (see: Grumeza , 2014. P. 49–51), were Sarmatian, arriving in this region of the north-west Pontic area or their descendants.

The finds at Hunedoara Timișană, together with the other Sarmatian cemeteries and settlements discovered over the last two decades in territories west of the province of Dacia, indicate that their settlement in these regions was significant only after the Marcomannic wars, when certain Sarmatian groups massively entered these territories, likely with Roman agreement and under their careful control. It is further certain that for between years 20–70/80 of the 2nd c. AD, there was no Sarmatian inhabitancy in the territory south the Lower Mureș. Such archaeological facts show that territories around the western and south-western borders of the province of Dacia were under efficient Roman control. The numerous Sarmatian settlements and cemeteries discovered in the plain part of the territory south the Lower Mureș river indicate the area was not incorporated, as argued until recently in the Romanian historiography ( Daicoviciu , 1942. P. 103; Benea , 1996. P. 114), in the province territory, but lay outside its south-western border located not far from the last westward forts along

»

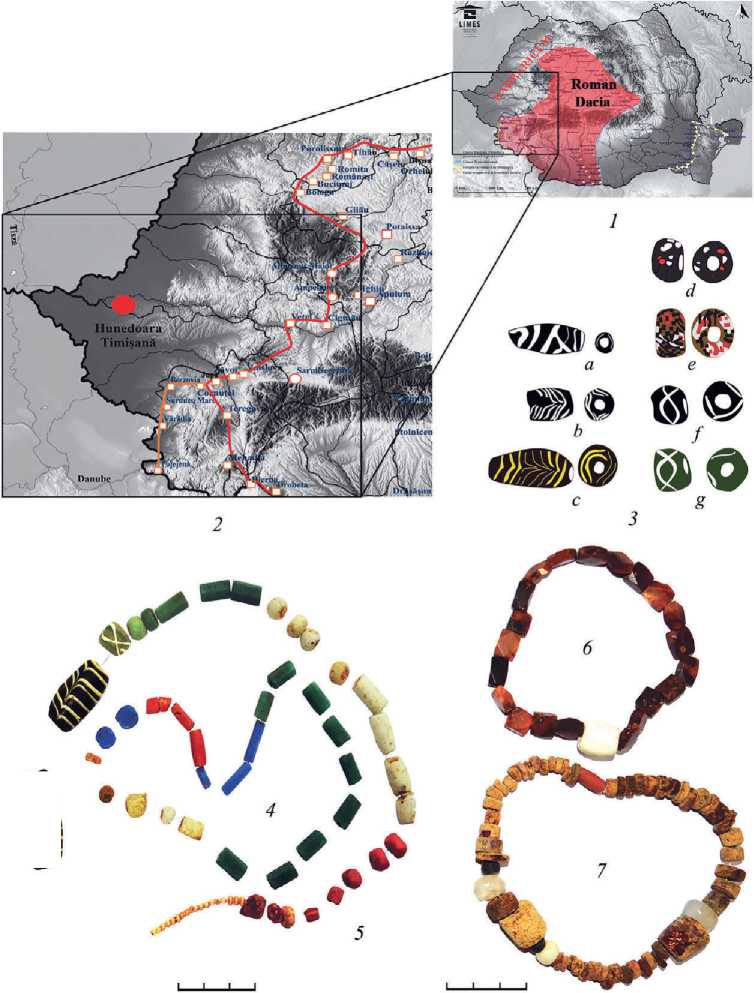

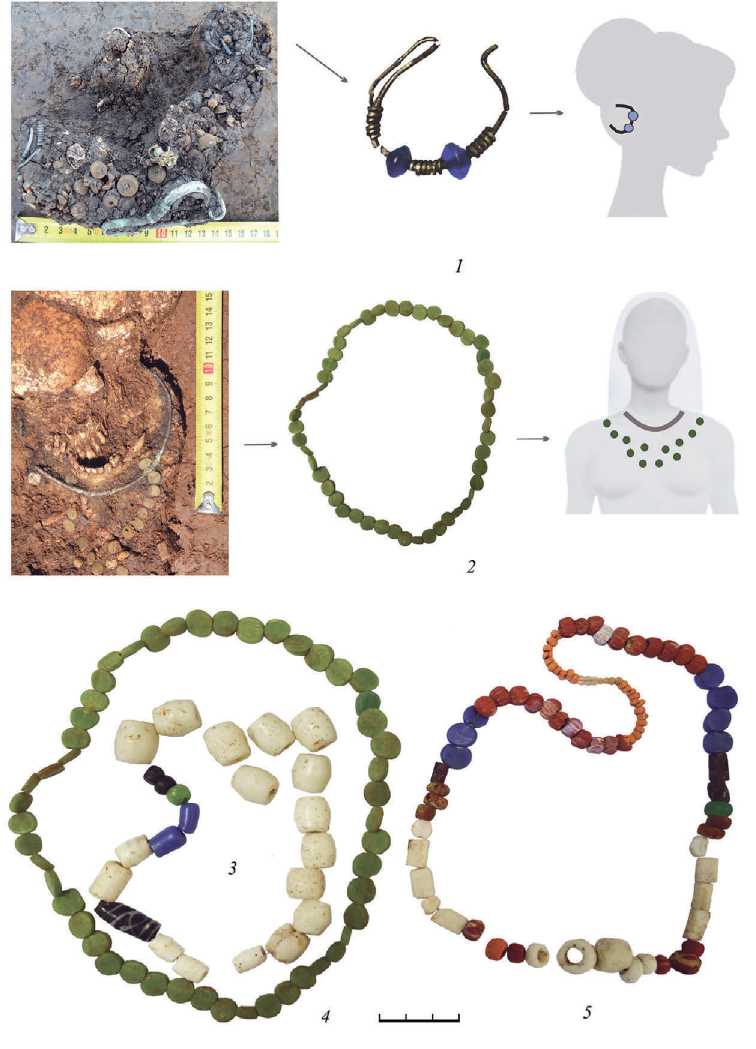

Fig. 1. The beads discovered in the Sarmatian burials of Hunedoara Timișană

-

1 – Limes Dacicus and Barbaricum (after: URL: www.limesromania.ro , with additions); 2 – location of the Hunedoara Timișană site

3–7 – beads at Hunedoara Timișană (after: Barcă , 2014): 3a – grave 7; 3b, d – grave 9; 3c, g, 4, 5 – grave 6; 3e – grave 2; 3f – grave 15; 6, 7 – grave 3

the Lederata-Berzobis-Tibiscum road. Concurrently, it is certain that this territory, under Roman control, lay though extra provinciam .

We shall discuss below the beads discovered in the Sarmatian burials of Hunedoara Timișană (Fig. 1), however, we shall also reference this type of artefacts yielded by other Sarmatian cemeteries investigated over the most recent years in the southwestern territories of Romania.

Beads fashion in Hunedoara Timișană and other contemporaneous cemeteries

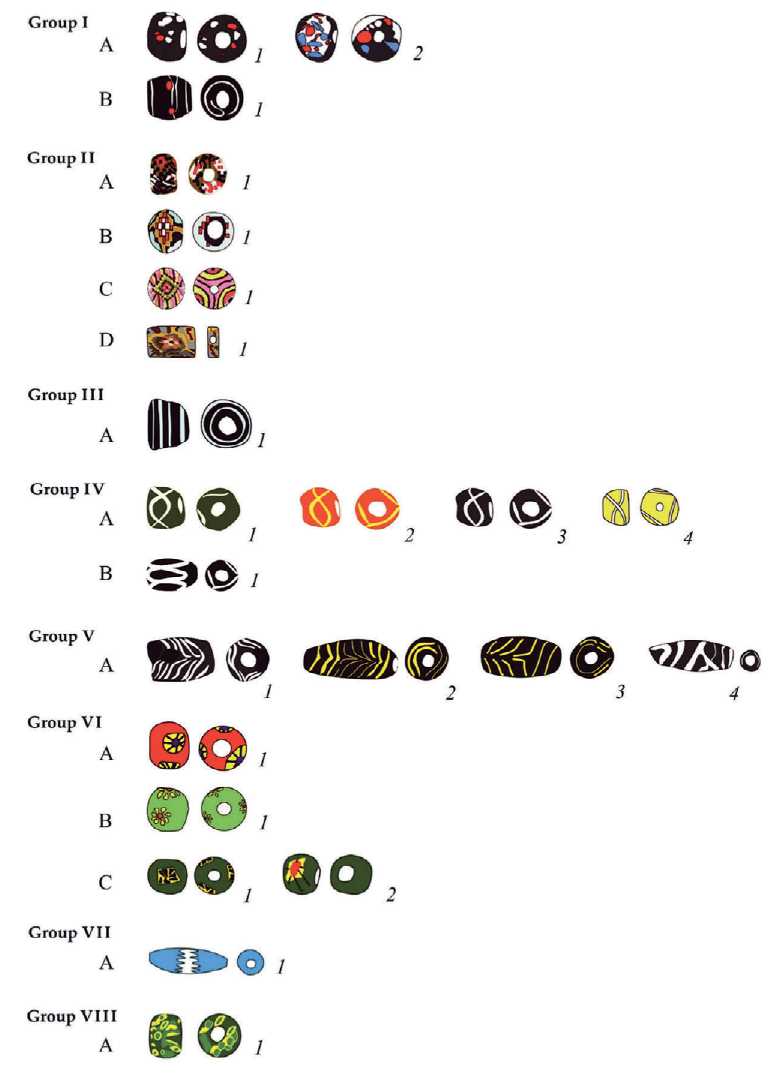

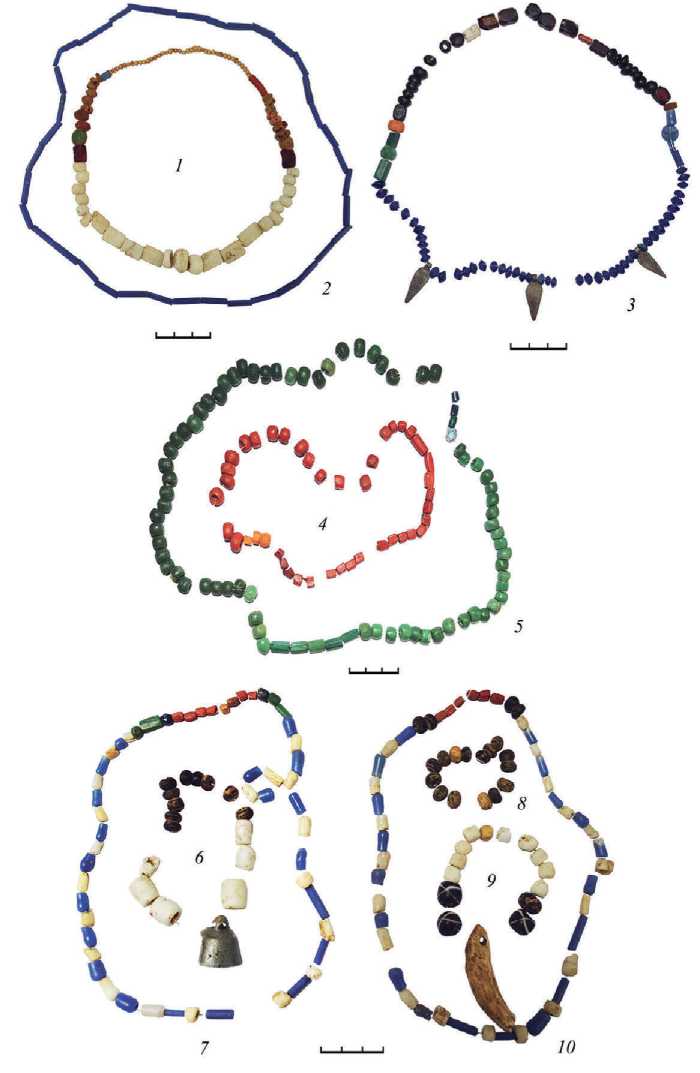

As archaeological material beads are a rather important historical source. They are artifacts that provide a large scale image of the trade relations, crafts development and especially aesthetic tastes and fashion. Beads are often found in the Sarmatian graves of the Great Hungarian Plain, their number in some cases reaching hundreds. Nevertheless, their number differs from one cemetery to another depending on the peculiarities of each site, the distance from the limes and quantity of Roman imports within the graves, as well as the resources available to the respective communities or the number of female graves in each cemetery. These circumstances hold also in the funerary complexes of the area between the Lower Mureș, Tisza and Danube: 1594 beads come from the eighteen graves at Foeni- Cimitirul Ortodox , 2204 beads from the 32 graves at Giarmata- Site 10 , while 24 graves at Pančevo- Vojlovica yielded 2215 beads (the cemetery contains 54 graves, mostly female) (see more recently: Grumeza, Bârcă , 2020) (Fig. 2).

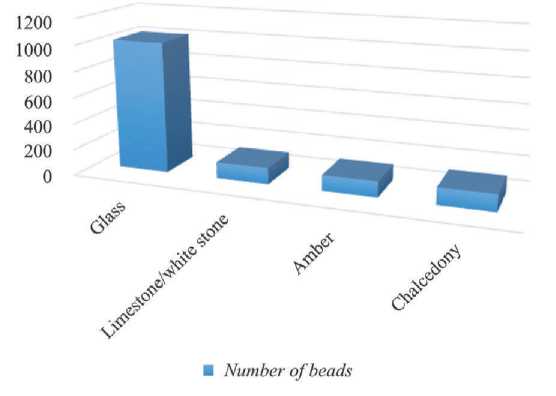

Beads are also the most numerous dress items in the graves at Hunedoara Timișană. A total of 1396 beads (beside other fragmentary pieces) were identified in the 14 graves analysed. In this cemetery, Grave 3 is noticeable with 592 beads, Grave 7 with 169 beads and Grave 9 with 201 beads – all three being female burials (young girls and adult female graves). While the majority of the beads were discovered in the neck and chest area of the dead, in some graves they were found also by the wrists and ankles, indicating in these cases, that they composed bracelets or anklets decorating the feet. From the point of view of the raw material, most beads from the analysed graves are made of glass (73 %), followed by beads made of a highly friable stone or limestone (9 %), and chalcedony (10 %). Amber beads represent 8 % of the investigated beads (Fig. 3).

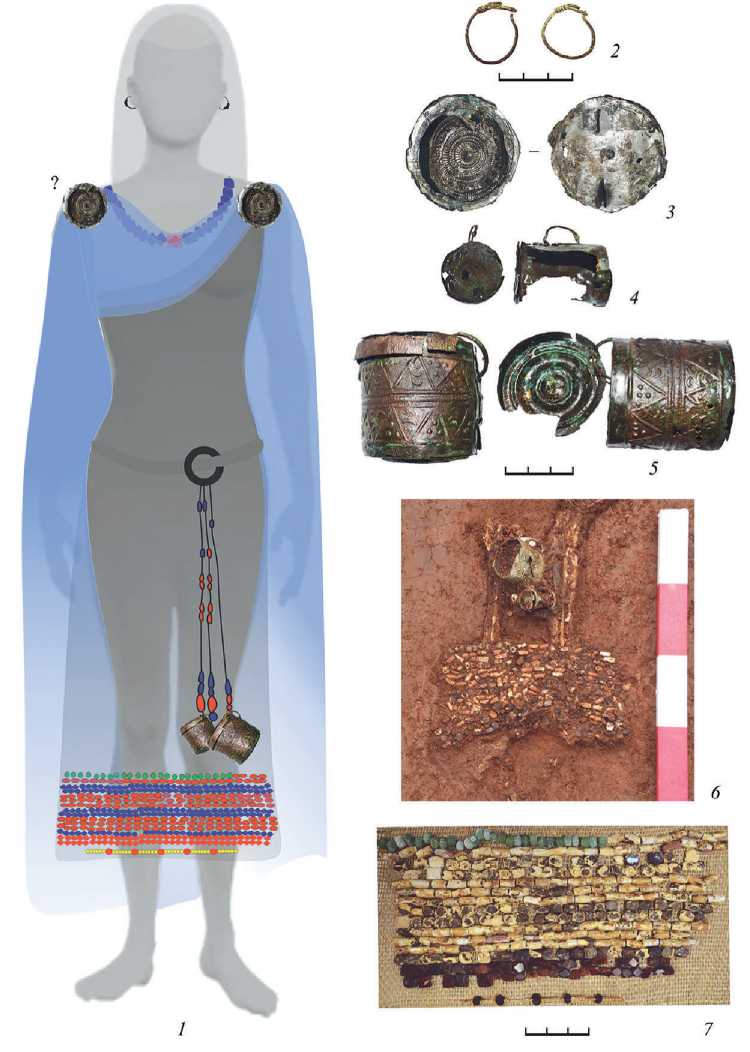

An example of glass beads worn as decoration on the lower sides of the coat/dress was identified in grave 3 from the Hunedoara Timișană cemetery, where 592 beads (mainly in glass) were identified. The many specimens set on rows in the ankle area were beaded on the garment in 16 successive rows (Fig. 4: 1, 6, 7 ). Each row followed a certain chromatic and structural symmetry, with mostly alternating polyhedral and biconical beads of complementary colours:

Row 1: 28 globular, green glass beads

Row 1–2: 27 biconical beads of white (?) glass (probably red, discoloured); their surface preserves a dark-blue metal patina here and there.

Row 3–4: 39 polyhedral beads of a highly friable stone, white; their surface still preserves a dark-blue metal patina here and there.

Fig. 2. Types of polychrome beads yielded by the Sarmatian graves from South-Western Romania (after: Grumeza, Barcă , 2020)

Fig. 3. Distribution of beads in the Hunedoara Timișană cemetery according to the raw material (after: Grumeza et al. , 2014)

Row 5–7: 54 biconical beads glass, white (?) (probably red, discoloured); their surface still preserves a dark-blue metal patina here and there.

Row 8–9: 39 polyhedral beads of a highly friable stone, white; their surface still preserves a dark-blue metal patina here and there.

Row 10–12: biconical beads glass, white (?) (probably red, discoloured); their surface still preserves a dark-blue metal patina here and there.

Row 13: 22 polyhedral beads of a highly friable stone, white; their surface still preserves a dark-blue metal patina here and there.

Row 14–15: 42 polyhedral chalcedony beads, flattened in profile, asymmetrically pierced.

Row 16: symmetrical combinations of 27 minuscule glass beads covered with gold leaf, in the shape of a simple sphere or formed of two, three or even four linked spheres and 5 disk beads, flattened, of porous, cherry glass ( Grumeza et al. , 2014. P. 122).

This beaded dress probably had over it a cape fastened with two brooches. One was fragmentary, but the other one was a unique box/capsule-type disk brooch. The brooch is made of two silver circular plates attached by a rivet made of the same metal. The outer side of the upper plate is decorated with a pattern in the granulation and filigree technique. The lower sheet is doubled on the inside by another sheet made of a lead, copper, silver and tin alloy. A spring fastening system is attached to the outer side of the lower plate. The bronze spring, preserved fragmentarily, was attached by a rectangular support provided with a hook. The spring chord was vertical and inserted through the hook. The pin did not survive. The brooch diameter is 5 cm (Fig. 4: 3 ). The brooch may be included in the category of disk brooches ( Scheibenfibeln ) represented by many types and versions. The specimen belongs to the type of disk brooches of the box/capsule type (Dosenfibel/Kapselfibel) very rare in both the Roman and Barbarian environments (for the analysis of this type brooches see: Bârcă , 2016).

Fig. 4. The Hunedoara Timișană cemetery, grave 3

1 – reconstruction of the dress worn by the deceased; 2 – earring; 3 – brooch; 4, 5 – pyxides; 6 – layout of some of the artefacts at the time of the find (after Barcă , 2014); 7 – successive rows of beads sewn on clothes

Similar clothes and decorations were noted in certain Sarmatian graves from Hungary, like Kiskundorozsma- Subasa (nearby Szeged) – grave 121, Site 26/78 ( Bozsik , 2003. P. 102, Fig. 4: 8, 10, 11 ). In the latter, the grave goods also included a bronze pyxis (Ibid. P. 102. Fig. 7: 6 ; 8: 6 ) identical with that in grave 3 from Hunedoara Timișană (Fig. 4: 5 ) ( Bârcă , 2014. P. 137, 149. Pl. 7: 5 ; 72: 4 ; Bârcă , 2017. P. 109, 110. Fig. 3: 3 ; 4: 2 ). A chromatic order of the beads sewn onto apparel was also noticed in grave 9 at Hunedoara Timișană. By the deceased’s feet were identified successive rows of globular beads, made predominantly of dull green, red and white glass. Each row maintained the same colour ( Grumeza et al. , 2014. P. 123; Bârcă , 2014. P. 155, 156. Pl. 26: 1 ; 61: 3 ).

The custom of embroidery-decorating garment hems with hundreds or even thousands of beads of various colours is recorded in the Sarmatian milieu of the Great Hungarian Plain as early as their settling of the area. The fashion peaks in the period after the Marcomannic wars, very likely influenced by the arrival in this area of new groups of Sarmatians by the end of the 2nd – early 3rd c. AD ( Kulcsár , 1998. P. 48–51, 96, 97, 112), when also emerge new funerary ritual and material culture elements. The hem-beading custom persisted in the 3rd c. AD and to a lesser extent in the 4th c. AD (Ibid. P. 51, 97, 112). A careful analysis of the funerary finds shows the fashion spread in the Sarmatian environment of the Great Hungarian Plain, with the note that in the Upper Tisza area and the adjacent territories in the northern part of the Great Hungarian plain, the custom is rarely found (Ibid. P. 51, 97, 112).

Combinations of glass and amber beads were also identified in the neck area of the dead in grave 7 at Hunedoara Timișană, again likely sewn onto the clothing and/ or part of necklaces (Fig. 5: 2 ). Most (50 pieces) are flattened discs made of green glass, set circularly in the chest area and the neck, and completed with globular, polyhedral or hexagonal beads (Fig. 5: 3–5 ). Another necklace made of beads and pendants comes from grave 17 at Hunedoara Timișană (Fig. 6: 3 ). Three lanceolate silver pendants were identified in the northern side of the grave pit (the head area), beside a collar and a bead string. The front side of the necklace was composed of pendants, intermingled with 47 biconical beads of blue glass and other pieces of various shapes and colours, predominantly globular, dark-coloured.

Beads – as earring parts – were documented in grave 14 from the Hunedoara Timișană cemetery (Fig. 5: 1 ). The earrings were made of a silver thread, with an extremity bent in the shape of a loop wound onto the specimen’s body and the other extremity bent as a hook. One of the earrings had attached to its body two slightly translucent dark-blue biconical glass ( Bârcă , 2014. P. 158. Pl. 35: 2 ; 73: 6 ). To date, this form is unique in the Sarmatian world. On the territory of Banat are known earring variations completed with carnelian beads and/or silver pendants, yet in other forms, found in graves 8, 9 and 14 in the Vršac- Dvorište Eparhije Banatska cemetery ( Барачки , 1961. Сл. VII: 8, 9 ; XI: 1, 2 ). Earrings with silver link, mixed with carnelian beads emerge in a series of Sarmatian graves from the cemeteries on the territory of Hungary, like those at Endrőd- Kocsorhegy ( Juhász , 1978. P. 107, 114. Pl. II: 9, 10 ), Madaras- Halmok ( Kőhegyi, Vörös , 2011. P. 263, 264. Fig. 256: 4 . Pl. 64: 4, 5 ), Szentes- Zalota ( Nagy , 1997. P. 69. Pl. 13: 1 ), Zsámbok ( Párducz , 1950. Pl. LXXII: 1, 2 ) and Szeged- Öthalom ( Párducz , 1960a. P. 98, 99. Pl. XXVII: 11, 12 ), etc.

Fig. 5. The Hunedoara Timișană cemetery.

Rare discoveries of the wearing of beads ( 1, 2 ). Beads ( 3–5 )

1, 2 – graves 14 and 7 (after: Grumeza, Barcă , 2020); 3–5 – grave 7 (after: Barcă , 2014)

Fig. 6. The Hunedoara Timișană cemetery. Beads. (after: Barcă , 2014)

1, 2 – grave 8; 3 – grave 17; 4, 5 – grave 9; 6–10 – grave 15

Another bead wearing manner was documented in grave 7 Hunedoara Timișană. In this case, beads were likely part of a fabric braid fastened centrally by a metallic ring. The objects were positioned to the left of the deceased, on a north-south axis. Similar belts likely existed in graves 3 (Fig. 4: 1, 4, 5 ), 6 and 15 as well. These were worn on the left side, completed with various pendants, bucket-pendants, pyxides, bells etc., hung by strings. Such dress objects were discovered in numerous female graves in the Szeged- Csongrádi út cemetery, graves 14, 19, 24, 25 ( Vörös , 1981. Pl. 2, 4, 8, 9). The presence of belts/cords is firstly marked by the find of a link (used to knot the cordon) and the stringing, on the left side, of beads, bronze bells, bone pendants, but also of knives or other objects that could be hung on the belt (Ibid. P. 132).

From above mentioned examples, we note that beads were very important dress objects in the Sarmatian female costume. They did not have only an aesthetic value, but also marked the status of women in society, either adolescent or adult. Furthermore, graves with numerous beads were also richly furnished, thus providing important clues for identifying the Sarmatian female elite from the area south the Lower Mureș river.

Final remarks

Following the analysis of the beads from the funerary finds at Hunedoara Timișană we may note the following:

-

1. The majority of beads from Hunedoara Timișană (and other contemporaneous cemeteries) were most likely crafted in the Tibiscum workshops ( Dacia Superior ). The functioning of these officinae (during the 2nd – early 4th cc. AD) may be connected to communities of craftsmen, who came from the Syrian-Palestinian-African regions following the establishment of military units in this particular area: cohors I Sagittariorum and numerus Palmyrenorum Tibiscensium ( Benea , 2004, P. 267). Physical-chemical analyses have shown that it was mainly the Syro-Palestinian workshops that supplied the imperial market with raw glass ( Antonaras , 2017. P. 6, 8, with further bibliography).

-

2. The anthropological-archaeological analyses made on various cemeteries ascribed to the Sarmatian culture (including Hunedoara Timișană) show that garments embroidered with various beads (on dress hems or trousers) was specific to adult women and adolescents ( Vörös , 1981), and had a similar function with that of a wedding dress or a garment that marks the entry of women into adult society.

-

3. Beads fulfilled various functionalities within the analysed graves: they were part of necklaces, belts, earrings or buttons, but most often were sewn onto female garments. We are dealing with the same fashion among the Sarmatian groups settling in most part of the Great Hungarian Plain (in the Marcomannic wars’ aftermath). Thus a constant characteristic of the female funerary costume through the entire 2nd – 3rd cc. AD was the embroidery with beads – a genuinely Eastern tradition – which can be nowadays easily reconstructed (Fig. 4: 1 ).

Список литературы Clothes make the woman: the beads fashion in the Sarmatian cemetery from Hunedoara Timisana

- Барачки Ст., 1961. Сарматски налази из Вршца // Рад војвођанских музеја. № 10. C. 117–143.

- Antonaras A. Ch., 2017. Glassware and Glassworking in Thessaloniki 1st Century BC – 6th Century AD. Oxford: Archaeopress. 383 p., tab. 35–54. (Archaeopress Roman Archaeology; 27.)

- Bârcă V., 2014. Sarmatian Vestiges Discovered South of the Lower Mures River. The Graves from Hunedoara Timișană and Arad. Cluj-Napoca: Mega Publishing House. 285 p.

- Bârcă V., 2016. Disc brooches of box/capsule type (Dosenfibel/Kapselfibel) in the Sarmatian environment of the Great Hungarian Plain. A few notes on their dating and origin // Orbis Romanus and Barbaricum. The Barbarians around the Province of Dacia and Their Relations with the Roman Empire / Ed. V. Bârcă. Cluj-Napoca: Mega Publishing House. P. 251–282.

- Bârcă V., 2017. Notes on the metal pyxides recently discovered in the Sarmatian environment south the Lower Mureș River // Plural. History-Culture-Society. Vol. 5. No. 2. P. 101–123.

- Bârcă V., Ursuţiu A., Cociş S. I., Stăncescu R. E., Ţuţuianu C. D., Irimuş L., Cociş Al., Sălcudean C., Bondric A., Brehuescu Al., 2011. Hunedoara Timişană, com. Şagu, jud. Arad, Punct: Autostrada Arad-Timişoara, tronson Arad-Seceani, km 23+170 – 23+690 (siturile B0_7-B0_8) // Cronica cercetărilor arheologice din România. Campania 2010. Sibiu: Muzeul Naţional Brukenthal, 2011. P. 187–192.

- Benea D., 1996. Dacia sud-vestică în secolele III–IV. Timişoara: Editura de Vest. 306 p.

- Benea D., 2004. Die Romischen Perlenwerkstaetten aus Tibiscum = Atelierele romane de mărgele de la Tibiscum. Timișoara: Excelsior Art. 287 p.

- Bozsik K., 2003. Szarmata sírok a Kiskundorozsma-subasai 26/78. Lelőhelyen // Úton-útfélen. Múzeumi kutatások az M5 autópálya nyomvonalán / Ed. Cs. Szalontai. Szeged: Móra Ferenc múzeum. P. 97–106.

- Daicoviciu C., 1942. Bănatul şi iazygii // Apulum. Vol. I. P. 98–109.

- Grumeza L., 2014. Sarmatian Cemeteries from Banat (Late 1st – Early 5th Centuries AD). Cluj-Napoca: Mega Publishing House. 413 p.

- Grumeza L., Bârcă V., 2020. Glass beads discovered in the Sarmatian cemeteries from south-western Romania // Archaeology and Early History of Ukraine. Vol. 3 (36). P. 402–415.

- Grumeza L., Rumegă-Irimuș L., Bârcă V., 2014. Beads // Bârcă V. Sarmatian Vestiges Discovered South of the Lower Mures River. The Graves from Hunedoara Timișană and Arad. Cluj-Napoca: Mega Publishing House. P. 120–133.

- Juhász I., 1978. Szarmata temető Endrődön // A Békés Megyei Múzeumok Közleményei. No. 5. P. 87–114.

- Kőhegyi M., Vörös G., 2011. Madaras-Halmok, Kr. U. 2–5. Századi szarmata temető. Szeged: Szegedi Tudományegyetem, Régészeti Tanszék. 455 p.

- Kulcsár V., 1998. A kárpát-medencei szarmaták temetkezési szokásai. Aszód: Osváth Gedeon Múzeumi Alapít. 153 p.

- Nagy M., 1997. Szentes és környéke az 1–6. században. Történeti vázlat és régészeti lelőhelykataszter // Studia Archaeologica. No. III. Szeged: A Móra Ferek Muzeum Evkönyve. P. 39–95.

- Párducz M., 1950. A szarmatakor emlékei Magyarországon = Denkmäler der Sarmatenzeit Ungarns. Vol. III. Budapest: Budapest Akadémiai Kiado. 402p. (Archaeologia Hungarica; vol. XXX.)

- Párducz M., 1960а. Hunkori Szarmata temető Szeged-Öthalmon // A Móra Ferek Muzeum Evkönyve. 1958–1959. P. 71–99.

- Párducz M., 1960b. Koraszarmata sírok Csanyteleken // Folia Archaeologica. No. XII. P. 71–74.

- Simonenko A. V., 1993. Sarmatian tribes of the Great Hungarian Plain and the north pontic region. Problem of migration // Specimina Nova. No. IX. P. 59–64.

- Simonenko A. V., 2001. On the tribal structure of some migrations waves of Sarmatians to the Carpathian Basin // International Connections of the Barbarians of the Carpathian Basin in the 1st–5th centuries A.D. / Eds.: E. Istvánovits, V. Kulcsár. Aszód-Nyíregyháza: Osváth Gedeon Museum Foundation – Jósa András Múzeum. P. 117–124.

- Vörös G., 1981. Adatok a szarmatakori női viselethez // Communicationes Archaeologicae Hungaricae. Budapest. P. 121–135.