Comparison of convolutional networks and transformers for generating 3D-models via binary space partitioning from a single object image

Автор: Gribanov D.N., Kilbas I.A., Mukhin A.V., Paringer R.A., Kupriyanov A.V.

Журнал: Компьютерная оптика @computer-optics

Рубрика: XI International conference on information technology and nanotechnology

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.49, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study explores the use of transformer architecture as an image encoder model for the task of 3D mesh generation from a single image. Traditionally, models based on autoencoder architecture perform such tasks, where an encoder produces a latent representation that a decoder subsequently converts into a 3D model. When processing image-based input, the ResNet18 convolutional network is a commonly used encoder. In this paper, we investigate replacing the convolutional network with a transformer-based approach while using binary space partitioning (BSP) for 3D object generation. Our experiments demonstrate that a transformer-based architecture, specifically the Compact Convolutional Transformer (CCT), can achieve performance comparable to its convolutional counterpart and exceed it both in quantitative metrics and visual quality. The best CCT-based model achieves a Chamfer Distance (CD) of 1.59 and a Light Field Distance (LFD) of 3907, whereas the convolutional variant attains a CD of 1.64 and an LFD of 3981. The CCT-based model also demonstrates superior 3D reconstruction quality on test samples. Additionally, the transformer model requires four times fewer parameters to achieve these results, though computational resources are two times higher in terms of Multiply-Accumulate operations (MACs). These findings indicate that the transformer-based model is more parameter-efficient and can achieve superior results compared to traditional convolutional networks in single-view reconstruction tasks.

Computer vision, 3D model, neural network, transformer, convolutional network, vector representation, latent vector

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140313288

IDR: 140313288 | DOI: 10.18287/COJ1863

Текст научной статьи Comparison of convolutional networks and transformers for generating 3D-models via binary space partitioning from a single object image

There exist various methods for modeling 3D objects, either as mathematical functions or as explicit 3D representations (e.g., meshes) [1 –7]. Many studies employ an autoencoder architecture to achieve this task. This architecture consists of two main components: an encoder, which generates a latent vector representation of the object, and a decoder, which reconstructs the 3D object from this representation. Autoencoders enable the processing of diverse data types, including images, point clouds, and voxels, as input data. When dealing with images, convolutional networks – most commonly ResNet18 [8] – are typically used as the encoder.

In BSP-Net [5], the authors use an autoencoder where the encoder is ResNet18 [8], while the decoder processes the latent vector and produces the final 3D object or shape by combining partitions from the binary space partitioning (BSP) process. Similar schemes are also used in other works [3, 9], but with different decoder architectures and systems. To further improve BSP-Net, several works have introduced additional enhancements [4, 10], such as the use of Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (NODE) [11] or improved loss functions [4].

In recent years, transformers [12] have been increasingly applied beyond natural language processing (NLP) to computer vision tasks [13– 17]. Studies have demonstrated that transformers can compete with convolutional networks and often outperform them in terms of memory efficiency and processing speed for certain tasks.

While transformers were originally developed for text processing [12], their application to computer vision was first demonstrated in [14]. This pioneering work introduced the concept of dividing an image into patches, each measuring 16 x 16 pixels, and processing them using a transformer network to generate the final output. This approach laid the foundation for subsequent research, leading to various modifications and new methodologies for applying transformers to image data [13, 15, 17]. Each successive study proposed refinements to improve performance or adapt transformer models more effectively for vision tasks.

Nevertheless, while the use of transformer architectures in computer vision has shown promise, they still face certain challenges. For instance, in DeepViT [17], the authors observed that increasing the depth of convolutional networks often improves performance, but the same does not necessarily hold for transformer-based architectures. They found that deeper transformer models tend to saturate in performance due to the nature of attention maps. As network depth increases, attention maps across layers become increasingly similar, reducing the model's effectiveness compared to shallower transformers or convolutional networks. To address this issue, the authors proposed a reattention mechanism, which regenerates attention maps at different layers, enhancing their diversity while maintaining low computational and memory costs.

Other works [15, 18] have found that transformer-based architectures tend to outperform convolutional networks on medium-to-large datasets when trained from scratch. However, on smaller datasets, transformers often underperform unless architectural modifications are introduced. For instance, the Compact Convolutional Transformer (CCT) [15] introduced a modified tokenization method that integrates convolutional layers, along with sequence pooling in the final layers, while retaining most of the original transformer structure from [14].

With these modifications, it is now possible to achieve 90 % accuracy on CIFAR-10 [19] in under 30 minutes of training using an NVIDIA 2080Ti GPU. The authors also conducted experiments on other smaller datasets, demonstrating the superiority of transformer architectures over convolutional networks in such scenarios.

These works demonstrate that transformer-based architectures are continuously becoming more powerful, much like convolutional networks did in earlier years.

This paper explores the feasibility of replacing convolutional networks with transformers for feature extraction and object vector generation in single-view reconstruction tasks. BSP-Net [5] is used as the central 3D model generation framework in our experiments, and the CCT [15] architecture is employed as the transformer-based encoder.

1. Experiment preparation

For our experiments on generating 3D models from a single image, we use the BSP-Net [5] system. This choice is motivated by its strong performance on relevant metrics, the availability of source code and pretrained models, and its suitability for modifications.

BSP-Net is a deep generative network that represents 3D shapes through binary space partitioning, enabling direct generation of compact polygonal meshes. The architecture consists of three main modules that operate on feature vectors extracted by an encoder. First, a multi-layer perceptron produces a set of plane parameters that define implicit equations for spatial subdivision. Second, a grouping operator combines these planes into convex shape primitives through selective neuron connections, where each convex is formed by the intersection of half-spaces defined by the planes. Finally, an assembly layer merges these convex primitives using union operations to reconstruct the complete shape. Unlike methods based on implicit functions that require expensive iso-surfacing procedures, BSP-Net directly outputs watertight polygonal meshes by applying Constructive Solid Geometry operations to extract explicit surfaces from the learned BSP-tree structure.

The primary advantages of BSP-Net lie in its ability to generate compact, low-polygon meshes that preserve sharp geometric features while maintaining computational efficiency during inference. The method produces meshes that are guaranteed to be watertight and can easily be textured or manipulated, addressing a key limitation of voxelbased and implicit function approaches that often result in over-tessellated surfaces. Training is unsupervised, requiring no ground truth convex decompositions, as the network learns to reconstruct shapes using a shared set of convex primitives across the entire training set. This structural consistency naturally establishes part-level correspondence between different shapes. Additionally, the direct mesh generation eliminates the need for isosurfacing algorithms, reducing inference time to approximately 0.5 seconds per mesh while producing representations that effectively capture both smooth surfaces and sharp edges – a capability that distinguishes it from methods generating only smooth approximations.

All training parameters and configurations follow those specified in BSP-Net [5]. For the dataset, a subset of ShapeNet [20] is used, comprising 13 different object classes and 24 views per object, with an overall count of approximately 40,000 objects. Each single image has a size of 137 pixels by height and width. During training, these images are center-cropped to 128 pixels by height and width. In the current experiments, only the encoder part of the model is trained, while the decoder remains frozen. The encoder model is trained based on latent vectors generated from a voxel encoder model from the BSP-Net work. All models were trained for 1000 epochs.

For the transformer-based model, we employ the Compact Convolutional Transformer (CCT) [15], chosen for its flexibility, open-source implementation, and ease of modification. Several variants of CCT are used in the experiments. We adopt the notation from the original work while introducing additional parameters to distinguish between model configurations. For example, CCT-18/7 x 2-3-384 consists of 18 transformer encoder layers, a tokenizer with 2 convolutional layers using 7 x 7 kernels, and an embedding dimensionality of 384. A multiplier of 3 determines the number of hidden neurons per transformer encoder layer (i.e., 3 x 384 hidden neurons). The following models were created and evaluated: CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256, CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256, CCT-28/7 x 2-4-256, and CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384.

While this notation captures the key architectural differences, we also introduce a custom variant based on CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384, referred to as CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384-v1. The primary modification in this version is the removal of the pooling layer in the second convolutional block of the tokenizer, which increases the output vector size from the tokenizer. Further details on this modification and its impact on performance are discussed in the next section.

For each architecture, Multiply-Accumulate operations (MACs) were calculated to measure the computational complexity of the architecture, as well as two metrics commonly used in 3D modeling: Chamfer Distance (CD) and Light Field Distance (LFD) [21] – to measure the quality of the final generated 3D objects. CD reflects the accuracy of vertex positions, while LFD evaluates the visual similarity between the modeled and original meshes. For both metrics, lower values indicate better performance.

2. Result and evaluation

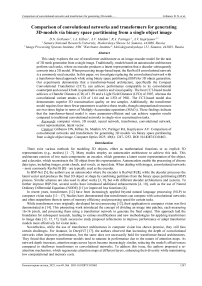

The training loss for different models is shown in fig. 1 with the first few epochs omitted from the plot due to high initial values. From the figure, we observe that each network converges to different final loss values. For example, ResNet18 achieves the lowest loss value, while CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256 and CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256 exhibit the highest. However, further analysis reveals that differences in loss values do not directly correlate with final result quality.

Loss value from training Single View Reconstruction

0 200 400 600 800

Epoch

Fig. 1. Training loss during training of different image encoders

The results of the experiments are summarized in tab. 1.

Tab. 1. Evaluation result for BSP-Net system with different image encoders

|

Image encoder architecture |

Training time, hours |

Number of parameters, millions |

MACS, Giga |

Metric |

|

|

CD |

LFD |

||||

|

ResNet18* |

- |

40 |

4.7 |

1.64 |

3946 |

|

ResNet18 |

10 |

40 |

4.7 |

1.68 |

3981 |

|

CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256 |

139 |

9 |

9.4 |

1.59 |

3907 |

|

CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256 |

13 |

10 |

0.8 |

2.21 |

4116 |

|

CCT-28/7 x 2-4-256 |

22 |

23 |

1.6 |

1.86 |

3999 |

|

CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384 |

28 |

33 |

2.3 |

1.82 |

4016 |

|

CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384-v1 |

66 |

33 |

8.5 |

1.82 |

3976 |

In the table, we also highlight the ResNet18 model pretrained in the original BSP-Net work, labeled ResNet18*, while another ResNet18 model was trained from scratch to evaluate training time and loss behavior. From the results, we observe that our retrained ResNet18 achieves performance similar to the original BSP-Net version. In the following sections, references to ResNet18 refer to our retrained model.

According to the table, ResNet18 was the fastest to train (10 hours), whereas the CCT architectures required up to 139 hours - nearly 14 times longer. The best-performing model, CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256, achieved a Chamfer Distance (CD) of 1.59 and a Light Field Distance (LFD) of 3907, which is slightly better than ResNet18. Notably, CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256 reached this performance while using four times fewer parameters (9 million vs. 40 million for ResNet18), demonstrating the parameter efficiency of the CCT architecture.

However, this conclusion does not apply to all CCT variants. The advantage of CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256 is likely due to its ability to process more input features, which also increases computational cost. Reducing the number of input features by a factor of 16 in CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256 speeds up training to the level of ResNet18 but leads to a performance drop. This model achieved a CD of 2.21 and an LFD of 4116 – an increase of 0.62 CD (39% higher) and 209 LFD units compared to CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256.

We also trained additional architectures with the same number of input features as CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256: CCT-28/7 x 2-4-256 and CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384. These models achieved nearly identical results. For instance, CCT-28/7 x 2-4-256 achieved a CD of 1.86 and an LFD of 3999 - only 0.27 CD (17 % higher) and 92 LFD units more than CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256. Although the metric differences were significantly reduced and results improved in these new variants, they still underperformed compared to both CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256 and ResNet18.

In CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384-v1, the number of input features was increased by a factor of 4 compared to CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384, yet there was no significant improvement in the metrics. This may be due to the limited magnitude of the increase in input features or the continued use of two convolutional layers in the tokenizer.

In conclusion, while CCT shows promise as a transformer-based architecture for 3D model generation, these experiments highlight the challenges in identifying the optimal architecture.

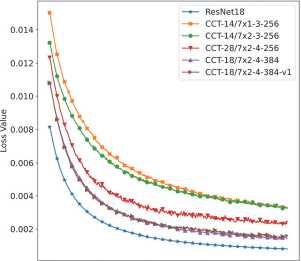

Fig. 2 shows visual differences between the trained models on three input samples from the test dataset. The first row presents the input images and the second row represents the source 3D objects in the form of meshes, while the remaining rows display the generated 3D results from each model, as indicated in the first column.

Fig. 2. Generation results from different models on three samples from the test data

From these results, we can observe that nearly every model generates a 3D shape that closely matches the corresponding input image - even CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256, which has the lowest quantitative metrics.

The first input is a bench, and all models produce a similar 3D object. The main differences lie in the surface quality of the models. For example, the ResNet18-based model produces a bench with extraneous, unnecessary parts on the legs. The clearest and most accurate 3D model is generated by CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256, which aligns well with its strong metric scores.

The second input is a car. The generated results resemble the input across all models, with one exception: CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384 produces a different car type than the input, whereas all other models correctly capture the vehicle. Interestingly, the model with the lowest metrics, CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256, does not exhibit this error.

The final input is a lamp. Results are consistent with those from the first example: differences are mostly visible in the lamp head, while the overall structure remains largely consistent across models.

The combination of quantitative metrics and visual comparisons confirms the potential of transformer architectures in this domain. Notably, CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256 performs on par with - or even surpasses - the traditional convolutional ResNet18 encoder, both in terms of visual quality and metric performance, while using four times fewer parameters.

These findings suggest strong prospects for future research and improvements. For instance, some studies have proposed distillation techniques between convolutional and transformer-based models using attention mechanisms [22], which result in highly efficient and precise transformer models. This approach could be applied not only between image-trained convolutional and transformer encoders but also with convolutional encoders trained directly on 3D data, such as voxel-based representations. Other research addresses training under data-scarce conditions [23], and we believe such techniques could enhance model robustness and generalization in any training setup.

3. Conclusion

In this paper, we investigated the feasibility of using transformers to generate 3D polygonal meshes from a single object image. The transformer model is used to generate an object vector, which is then passed to a BSP-based decoder to construct the final 3D mesh. As the transformer encoder, we adopted the Compact Convolutional Transformer (CCT), which is well-suited for image-based tasks.

Our experiments demonstrate that CCT-based transformer architectures can deliver comparable – and with certain configurations, superior – results to traditional convolutional networks, while requiring significantly fewer parameters. Several CCT variants were evaluated, including CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256, CCT-14/7 x 2-3-256, CCT-28/7 x 2-4-256, CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384, and CCT-18/7 x 2-4-384-v1, to analyze the impact of architectural choices, particularly the number of input features and tokenizer configuration. The best-performing CCT model, CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256, achieved a Chamfer Distance (CD) of 1.59 and a Light Field Distance (LFD) of 3907, compared to the ResNet18 baseline's CD of 1.64 and LFD of 3981. Visual analysis of test samples further confirmed the quantitative results, showing that CCT-14/7 x 1-3-256 produces cleaner and more accurate 3D reconstructions compared to ResNet18, with fewer artifacts and better surface quality. This shows that the transformer model not only competes in output quality but also does so with four times fewer parameters, highlighting its parameter efficiency. However, this parameter efficiency comes with increased computational costs, as the CCT model requires approximately two times more Multiply-Accumulate operations (MACs) and significantly longer training times – up to 139 hours compared to 10 hours for ResNet18.

With continued research and refinement, we believe that transformer-based models can achieve even better results. The rapid advancement of transformer techniques has already introduced many simple yet powerful improvements, opening promising directions for future exploration in 3D reconstruction and beyond. For instance, distillation techniques between convolutional and transformer-based models [22] and methods for training under data-scarce conditions [23] could further enhance model performance and robustness. The parameter efficiency and superior quality results compared to CNN models demonstrated by applying the existing CCT architecture to our 3D reconstruction task suggest potential applications in specialized imaging systems, such as single-pixel imaging methods where parameter efficiency and quality is crucial [24, 25]. Furthermore, the compact nature of the CCT architecture makes it particularly suitable for deployment in real-world computer vision systems, including quality inspection applications [26], agricultural monitoring and weed detection [27], structural defect assessment [28], mobile robotics navigation [29], and real-time object detection on resource-constrained devices [30]. These applications would benefit from the parameter efficiency, which correlates with reduced computational requirements, while maintaining the high reconstruction quality that our adapted transformer-based approach demonstrates.

Acknowledgements

The research was carried out within the state assignment theme FSSS-2023-0006.