Correlation between economic growth, oil prices and the level of monetization of economy in oil and gas exporting countries: challenges for Russia

Автор: Domashchenko Denis Viktorovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Socio-economic development strategy

Статья в выпуске: 1 (43) т.9, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The low monetization of the Russian economy occasionally provokes serious debates on the necessity of its substantial increase in order to promote economic growth. However, this step will not change the crisis situation due to the counteraction of structural factors and flaws in monetary regulation. The study of the level of monetization in the periods of stagnation and decline in oil prices in the countries that export raw materials shows it is impossible to promote economic growth only at the expense of additional money supply. The policy of inflation targeting in commodity-based developing economies proves efficient only if commodity prices are growing, when monetary policy restrains excessive credit activity. At present, falling oil prices and a liberal foreign exchange regime stimulate high inflation and decline in credit activities. Therefore, during the time of negative commodity market conditions, it is necessary to readjust monetary regulation so that it could counteract deleverage processes in the real sector of economy. The dynamics of credit activities should become the main regulating indicator instead of the consumer price index. The Bank of Russia should start lowering interest rates if credit activities are declining, even if the consumer price index remains high. It will be possible to return to neutral monetary policy only after the falling trend in oil prices is reversed and credit activities increased.

Monetization, banking system, inflation targeting, financial stability, loans

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223812

IDR: 147223812 | УДК: 336.741.236.2 | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2016.1.43.6

Текст научной статьи Correlation between economic growth, oil prices and the level of monetization of economy in oil and gas exporting countries: challenges for Russia

The level of monetization of the economy is essential for creating the necessary conditions for successful economic development. For example, Ya. M. Mirkin in [8, p. 22] shows that “low monetization and the saturation of the economy with financial assets at the level of developing countries that are in the lower zone of per capita income lead to the deceleration of economic growth, excessive dependence on short investments of nonresidents, to the weakness of the resource potential of the financial sector, to inflated price of money in the economy”. The work [12] also confirms the stable relationship between monetization and GDP per capita for a sample of 120 countries. Finally, the author of [1] argues that low values of the coefficients of monetization of the Russian economy and high speed of money circulation indicate the insufficient trust of economic agents in the national monetary system, which, as a rule, is an inevitable consequence of high inflation, as evidenced by the state of the Russian economy. The patterns examined by the authors cover a very wide range of countries with source actual data collected in the period of growth of the world economy and the upward cycle in oil prices. However, since the middle of 2014, there is a downward trend in oil prices, which negatively affects the economy of hydrocarbons exporting countries.

Money is a key component in calculating the level of monetization of the economy. Money represents information about the ability of economic agents to perform an economic or financial transaction. Nowadays, money emission depends on the ability of the banking system, economy and government to generate debt obligations. The stronger and the more diversified the economy and economic ties, the greater the capacity to carry out monetary emission under the new debt obligations. Thus, the level of monetization of the economy is largely determined by economic structure, by the activity of business entities and by the depth of the financial system. The Ministry of Economic Development of Russia clearly states that the “growth of monetization coefficient means that the accumulation of financial resources in the financial sector goes faster than the growth rate of the nominal gross domestic product (GDP). This process does not ensure the growth of investment volumes, it changes the structure and diversifies the ways of formation of investment sources” [14]. Does it mean that the government does not pay attention to the calculations and conclusions made by economists?

Developed countries are characterized by the high level of monetization; however, the situation is not so clear with regard to commodity export oriented countries. Oil and gas producing countries can be divided into two groups: the countries where GDP per capita is extremely low and most people live below the poverty line, and the countries where GDP per capita is very high and the population is relatively wealthy.

The success of the second group of countries is associated not so much with a low number of population relative to the volume of commodity exports (e.g. Norway and Canada), as with the ability of the financial system to accumulate and redistribute savings effectively, which ultimately has a positive effect on the overall level of monetization of the economy.

However, the increase in the level of monetization does not mean the automatic and accelerated GDP growth. There is an opinion that the growth of monetization of the economy can increase economic growth rates. In our opinion, this is true only in the framework of oil prices growth in the countries in which monetization level was insufficient. The work [4] reveals a positive correlation between the positive increase in the level of monetization of the economy and GDP per capita. But attention is drawn to the limit of monetization coefficient equal to 54%, under which its further increase does not produce a significant effect on the increase in GDP per capita.

The simple increase in the level of monetization in the conditions of the falling trend in oil prices will not stimulate the growth of the Russian economy that is oriented mainly on the export of hydrocarbons, because the set of factors that in modern conditions goes together with a significant reduction in foreign exchange export revenues will in any case outweigh the positive effects of developing monetization.

Table 1 shows the macroeconomic indicators of countries focused on oil and gas exports, among which we can see different levels of monetization of their economies; and the degree of dependence of GDP on oil prices dynamics in the countries under consideration does not depend on the dynamics of monetization of their economies.

We can see that the countries are arranged in descending order by share of oil and gas in total exports of goods. So, Russia has only 70% of oil and gas export, among other goods; but the correlation between the dynamics of its GDP in relation to the dynamics of oil prices reaches 83%. In addition, the fluctuations in GDP dynamics in relation to the changes in oil

Table 1. Calculated indicators of dependence of macroeconomic indicators of the countries focused on oil and gas exports on the dynamics of oil prices from 2000 to 2014

|

Country |

Rank according to the monetization of economy |

Share of oil and gas exports in total exports, % |

Correlation coefficient of the dynamics of GDP and oil prices, % |

Beta coefficient of GDP dynamics for oil prices, % |

Monetization of economy (М2/GDP, %) |

|

|

2000 |

2014 |

|||||

|

Algeria |

2 |

97 |

95 |

53 |

38 |

71 |

|

Nigeria |

13 |

97 |

54 |

71 |

22 |

20 |

|

Kuwait |

3 |

94 |

93 |

70 |

71 |

65 |

|

Azerbaijan |

12 |

93 |

68 |

66 |

16 |

28 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

5 |

86 |

98 |

56 |

45 |

55 |

|

Kazakhstan |

10 |

78 |

80 |

57 |

15 |

34 |

|

Russia |

9 |

70 |

83 |

64 |

22 |

44 |

|

Norway |

7 |

69 |

88 |

38 |

48 |

53 |

|

UAE |

11 |

67 |

93 |

48 |

33 |

30 |

|

Colombia |

8 |

56 |

76 |

38 |

26 |

47 |

|

Bolivia |

1 |

55 |

52 |

20 |

52 |

78 |

|

Canada |

4 |

26 |

84 |

32 |

72 |

63 |

|

Mexico |

6 |

13 |

75 |

28 |

23 |

54 |

Source: calculated by the author using the source data of Thomson Reuters.

prices account for 64% which is an impressive figure. According to this index, only Nigeria (71%), Kuwait (70%) and Azerbaijan (66%) are in a worse situation than Russia. However, in these countries the share of oil and gas exports significantly exceeds 90% of the total exports of goods.

The highest correlation between the dynamics of oil prices and the GDP dynamics is typical for countries of the Middle East, fluctuations in their GDP growth is significantly lower than in Russia.

After 15 years, Russia’s economic growth rate still depends to a great extent on the fluctuations in world commodity markets.

According to the results of the graphical analysis of correlation coefficients and beta dynamics of nominal GDP relative to world oil prices (see Fig. 1 ) we determined four groups of hydrocarbons exporting countries that are characterized by different degree of dependence of economic growth on changes in oil prices.

Russia is in the “risk group” (with high factors of correlation and beta) together with Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Kazakhstan.

The situation is slightly better in Azerbaijan and Nigeria: their GDP, despite lower correlation with oil prices, also reacts strongly to the direction of the trend in oil prices.

Figure 1. Correlation and variability (beta coefficient) of GDP depending on oil prices since the beginning of the 21st century

65%

55%

си

си о

45%

си

35%

25%

Ml

M Ml Ml M Ml Ml

Ml

■ Ml

Hl Ml

ни

Ml Ml Ml

НИИ

Hl Ml

ни

нн

Ml

3!Е11

меги

СдЕНяВ

г way

■ ин

■■■ СжСаваиа^Н

В ИН ■■■■■■■■■

mi

Ml

Ml Ml Ml

15%

50% 55% 60% 65% 70% 75% 80% 85% 90% 95% 100%

Correlation coefficient

Source: author’s calculations based on source data from Thomson Reuters Agency.

UAE, Norway and Canada managed to achieve more smoothed fluctuations in GDP, despite their strong correlation with the dynamics of oil prices.

Finally, Bolivia, Mexico and Colombia form a group of countries that react to oil market trends very weakly.

In the case of stabilizing oil prices, and even more when the trend in oil prices is downward, the majority of countries under consideration show the decorrelation between the indicators of monetization of the economy and the pace of their economic growth. In this period, even the growth of monetization of the economy may well be accompanied by reduction in GDP.

In the near future the Russian economy will not be able to get rid of the high dependence of its GDP on oil prices; however, it is crucially important to reduce the amplitude of fluctuations in the growth rate of the economy in response to the oil trend. In this case the key objective is to reduce the beta coefficient of GDP to 25–30%, as in Norway or Canada.

It does not make sense to continue to increase the monetization of the economy without its structural reforms, but it is essential to promote conditions for financial stability.

Financial stability, in the opinion of the author, is ensured through the simultaneous increase in lending and in money supply. The growth of lending that is observed in virtually all commodity export driven economies and that promotes the processes of economic restructuring and diversification provides adequate growth of revenues and indicators of money supply. The terms of financial stability ensure the balanced development of the economy and protection from subsequent external opportunistic risks.

In case of mismatch between the increase in loan debt and money supply aggregates, we observe the formation of financial instability conditions that create risks in the implementation of external opportunistic risks.

Table 2 shows that the strongest loan expansion since the beginning of the century occurred in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and

Table 2. Growth rates of indicators (2014/2000), at the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar

|

Country |

Banking sector loans |

Money supply М2 |

GDP |

International reserves |

Population |

Currency |

|

Azerbaijan |

43.83 |

24.51 |

14.26 |

23.27 |

1.19 |

0.88 |

|

Kazakhstan |

36.51 |

25.61 |

11.60 |

13.80 |

1.16 |

0.80 |

|

Russia |

31.17 |

14.63 |

7.16 |

13.96 |

0.98 |

0.48 |

|

Algeria |

20.30 |

7.31 |

3.91 |

13.75 |

1.28 |

1.19 |

|

UAE |

8.94 |

3.44 |

3.85 |

5.75 |

3.10 |

1.00 |

|

Colombia |

7.79 |

6.85 |

3.78 |

5.20 |

1.21 |

0.94 |

|

Nigeria |

7.70 |

11.29 |

12.26 |

3.71 |

1.45 |

1.18 |

|

Saudi |

7.29 |

4.89 |

3.96 |

35.71 |

1.37 |

1.00 |

|

Arabia |

5.88 |

4.15 |

4.51 |

4.52 |

1.80 |

1.07 |

|

Kuwait |

3.44 |

3.21 |

2.92 |

2.32 |

1.14 |

0.60 |

|

Norway |

2.93 |

6.11 |

4.07 |

12.78 |

1.30 |

0.92 |

|

Bolivia |

2.90 |

4.36 |

1.88 |

5.50 |

1.20 |

0.62 |

|

Mexico |

2.57 |

2.13 |

2.42 |

2.30 |

1.16 |

1.58 |

Source: calculated by the author using the source data of Thomson Reuters.

Russia – the former Soviet republics focused on hydrocarbon resources. However, the pace of economic growth in these countries was 3–4 times slower than the growth of the total loan debt in the economy. In most cases the majority of money supply generated through lending either left the country in the form of capital outflow or was disinvested through consumer lending of imported goods instead of increasing domestic production with high added value.

If loan growth significantly exceeds GDP growth, we can say there are the risks of fueling the credit bubble. If the growth of loans corresponds to the growth of money supply, then it is premature to talk about the credit bubble, because the entire money supply generated in the process of lending is concentrated in the national banking system and forms the resource base for future economic development.

The countries that experienced inadequate credit expansion together with limited monetization will have more problems in dealing with the crisis associated with the deterioration of commodity market environment. And vice versa, in the countries that carried out the policy of simultaneous growth in lending and savings, oil deflation will not have negative effects on the state of their economies. These countries include, first of all, Norway, Canada, Mexico and Bolivia.

It is interesting to note that the resistance of GDP to oil prices fluctuations is typical of those countries in which there was a simultaneous growth of credit and money supply over the last 15 years, namely in Canada and Norway. And in those countries where the growth of money supply 1.5–2 times exceeded the growth of debt load, the fluctuations of oil trend had almost no impact on the amplitude of GDP fluctuations.

Currency regime is the most significant factor in providing the required level of monetization in raw materials producing countries. Under the “currency board” regime in the country the parameters of money emission are “anchored” to the country’s export revenue and to the algorithm of formation of international reserves. If the national currency is freely floating, then it is necessary to develop domestic debt market and bank lending for the adequate growth of money supply. Nominally the tasks of the Bank of Russia remain the same: to ensure the stability of the ruble and price stability. The author agrees with M.V. Ershov that “the Bank of Russia has not yet managed to achieve either the first goal – to preserve the stability of the ruble, or the second goal – to ensure price stability” [6, p. 38]. At the same time, there is no clear answer as to which currency regime is effective in an open economy. For instance, S.R. Moiseev, on the basis of analyzing dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models, notes that “in some cases, for example, if there is a threat of sudden cessation of foreign capital inflows, lowered nominal price rigidity or in the prevalence of pricing in the currency of the consumer (importer), researchers recommend to stick to the policy of fixed exchange rate. However, the vast majority of economists believe that, in the absence of speculative attacks in the currency market and non-fundamental fluctuations in the exchange rate, an optimal regime is the floating exchange rate regime” [9, p. 22].

In the end of 2014, Russia abandoned the policy of currency corridor and moved to inflation targeting, therefore, it chose a way to support money emission through the growth of the debt market. However, the past year that was characterized by the inflation targeting regime in the conditions of falling trend of oil prices has exposed the stagflationary signs of such a policy. A.E. Dvoretskaya writes: “...While not denying the enormous potential inherent in the mechanism of inflation targeting, we note that its use gives good results only in a stable economic and political environment, and in a diversified economy” [2, p. 21]. The problem of the floating exchange rate in Russia also consists in the fact that the foreign exchange market did not always react adequately to the changing dynamics of the oil trend, no matter how the Bank of Russia and the Ministry of Finance wanted it. For example, we can observe the slowdown in the weakening of the ruble in October – December 2015 against the speed up of the fall in oil prices in the same period. In order to speculate successfully against the ruble, it is necessary to show an increased demand for the currency, but the amount of free rubles in the market is becoming smaller and international speculators by the end of 2015 have turned their attention to attacks against the South African rand and Brazilian real.

In this regard, a softer interest rate policy of the Bank of Russia should “help” speculators borrow rubles at a lower interest rate in order to bring the weakening of the ruble to the levels recommended by the budgetary policy of Russia, namely 3,200 rubles per barrel of oil. As of mid-January 2016, the ruble strengthened against the balanced level provided for in the federal budget in 2016 by 25% (2,500 rubles per barrel of oil), and with the current interest rate policy of the Bank of Russia, it will be not so easy to provide the necessary devaluation of the ruble to a level more “comfortable” for the budget. The situation is changing towards the necessity to have a weaker ruble. If at the end of 2014, the Bank of Russia raised interest rates to protect the ruble from speculators, then exactly one year later there emerges the issue of the “strong ruble” that hampers the execution of the budget.

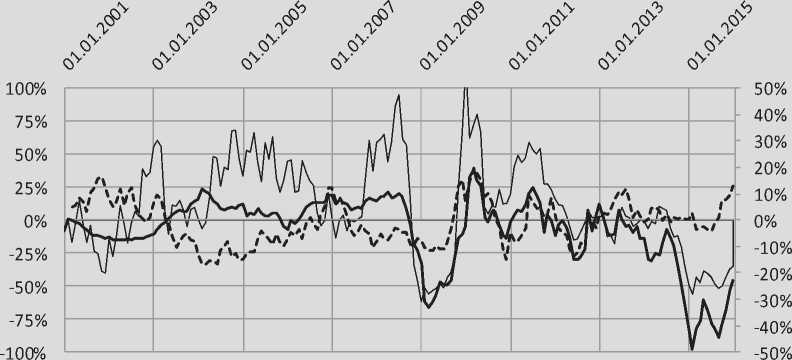

Since the beginning of the 21st century, oil prices have formed four upward, three downward and three consolidation mediumterm trends. Moreover, the increase in oil prices within the framework of these trends lasted 83 months, the decrease lasted 38 months, and the neutral tone lasted 34 months. In December 2015, the price of Brent crude oil returned to the level of the spring of 2004, which started a prolonged upward trend that lasted 29 months ( Fig. 2 ). The recent upward trend in 2009–2012 started with approximately 35 U.S. dollars per barrel and lasted also 29 months.

The specific feature of the current downward trend of oil prices consists in the fact that it is more extended in time (by February 2016, the decline has been going on for 17 months) and has much smaller potential for a trend reversal in the near future in view of objective fundamental and technical factors.

Figure 3 shows the dynamics of prices for Brent crude oil since 1987. It is obvious that the bubble has burst in this market, and now

Figure 2. Annual increase in the prices for Brent crude oil (left scale), the Russian ruble and the U.S. dollar index

I I Prices for Brent crude (left scale)

Increment Rub/USD (right scale)

Increment USDx (right scale)

Source: calculated by the author with the use of the data provided by Thomson Reuters.

Figure 3. Prices for Brent crude for the past 28 years

Source: Thomson Reuters.

the prices above 80 U.S. dollars per barrel are viewed as completely biased. In the medium term, we can expect the consolidation of oil prices in the range from 10 to 40 U.S. dollars, as it was since the late 1980s and up to 2004 (the average price per barrel of oil in 1987– 2004 was 20.6 million U.S. dollars). Given the inflation of the U.S. dollar that has accrued since 1999 in the amount of 44%, we can say that today the price of oil adjusted for inflation of the U.S. dollar is at the level of 29.7 U.S. dollars per barrel that should not be perceived as a disaster, but it is an average level with regard to inflation.

Table 3 shows comparative data on the dynamics of oil prices and the consumer price index in the United States and Russia. Even with the significant decline in oil prices over the past 16 months in comparison with the inflation of the U.S. dollar, their current level is 2.4 times higher than in 1999.

Thus, aside from the emotional assessment of the situation, we can note an absolutely objective nature of events occurring in the oil market. Further decline of oil prices in the Russian rubles is also very likely.

Having changed the currency regime in favor of the free float of the Russian ruble, the Bank of Russia should use the official interest rate in the regulation of economic activity and fulfillment of the task of balancing the budget. By the end of 2015, Russia’s foreign exchange market has come to equilibrium, but the amplitude of its fluctuations is historically two times lower than the fluctuations of oil prices. Thus, another reduction in the price of oil in rubles will cause a significant decline in domestic consumption.

The consequences of the credit bubble, which was inflated in the Russian Federation during the periods of continued rise in oil prices, generally have a negative impact on the current state of the economy: credit risks are growing, it is more and more difficult for enterprises to service the accumulated debts, investment pause is prolonged. The Bank of Russia needs to pay more attention not only to the rate of consumer inflation that serves as the basis for its interest rate policy, but also to the indicators that characterize the components of financial stability of the banking system. So, in the current conditions it is necessary to

Table 3. Dynamics of oil prices and inflation indicators in the U.S. and Russia

|

Date |

Price of Brent crude, U.S. dollars/barrel |

Price of Brent crude, rubles/barrel |

Accumulated inflation of the Russian ruble since Jan. 01, 1999 |

Accumulated inflation of the U.S. dollar since Jan. 01, 1999 |

Oil prices/ CPI in U.S. dollars |

|

Jan. 01, 1999 |

10.5 |

217.7 |

- |

- |

1.00 |

|

Jan. 01, 2004 |

30.3 |

892.5 |

150.8% |

12.5% |

2.57 |

|

Jan. 01, 2009 |

35.9 |

1052.9 |

329.4% |

28.3% |

2.67 |

|

Jan. 01, 2014 |

110.0 |

3590.8 |

511.6% |

42.2% |

7.37 |

|

Jan. 01, 2015 |

55.3 |

3108.3 |

581.1% |

43.3% |

3.67 |

|

Jan. 01, 2016 |

36.5 |

2660.1 |

663.2% |

44.8% |

2.40 |

smooth the processes of deleverage in the real sector of the economy where the interest rate should be the main instrument of regulation. Given the limited money supply growth in 2015, the Bank of Russia has an opportunity to pursue a much more accommodative monetary policy. The current high interest rates of the Bank of Russia artificially preserve the increased interest bank margin, which only increases the disparity between the growth rates of the accumulated debt and the aggregate money supply M2. At that, the indicator of monetization of the economy will increase simultaneously with the aggravation of the recession, i.e., the level of monetization will increase on the background of the downturn in the economy.

When the growth rate of the accumulated debt and the aggregate of M2 money supply are aligned, the Bank of Russia will be able to conduct neutral monetary policy without jeopardizing the financial stability of the banking system.

At present, pursuing its interest rate policy, the Bank of Russia pays attention to the consumer price index and inflation expectations; this excludes the possibility of maneuver to mitigate the processes of deleverage in the real sector of the economy.

A more explicit identification of the trend of lowering official interest rates by the Bank of Russia would not lead to a substantial increase in lending activity. Economic agents in the conditions of gradual but steady decline in interest rates, as a rule, are in no hurry to expand lending, especially if the economy is in a state of decline. The gradual reduction of interest rates enables soft refinancing of the accumulated debt for current borrowers on more favorable terms. Enterprises will spend less on servicing the current debt, creating the conditions for dealing with other costs of the enterprises, which ultimately reduces the prices of final products. In other words, at the present time it is especially important not to limit access to credit by restricting money supply, but to promote more favorable conditions for the refinancing of the accumulated debt in order to help business survive.

If the Bank of Russia can be proactive, then its trend aimed to decrease the official interest rate will help meet the inflation target level in 2017. Otherwise, the rapid credit contraction is inevitable along with the aggravation of the recession.

If the Bank of Russia focuses on the quantitative indicators of financial stability, if it synchronizes the rate of growth of monetary aggregates and credit activity by using the monetary policy instruments, then there will be no new imbalances in the monetary sphere hindering socio-economic development.

Список литературы Correlation between economic growth, oil prices and the level of monetization of economy in oil and gas exporting countries: challenges for Russia

- Andrianov V.D. Monetizatsiya ekonomiki: global’nye tendentsii i rossiiskie realii . Biznes i banki , 2013, no. 34 (November), pp. 1-3.

- Dvoretskaya A.E. Vzaimodeistvie denezhno-kreditnoi i byudzhetnoi politiki kak faktor finansovoi ustoichivosti . Den’gi i kredit , 2015, no. 10, pp. 20-28.

- Dvoretskaya A.E. Tselepolaganie v sovremennoi denezhno-kreditnoi politike Rossii . Bankovskoe delo , 2014, no. 7, pp. 6-14.

- Grekov I.E. O sovershenstvovanii podkhodov k opredeleniyu monetizatsii ekonomiki i obosnovanie ee optimal’nogo urovnya . Finansy i kredit , 2007, no. 11, pp. 60-70.

- Ershov M.V., Tatuzov V.Yu., Ur’eva E.D. Inflyatsiya i monetizatsiya ekonomiki . Den’gi i kredit , 2013, no. 4, pp. 7-12.

- Ershov M.V. Vozmozhnosti rosta v usloviyakh valyutnykh provalov v Rossii i finansovykh puzyrei v mire . Voprosy ekonomiki , 2015, no. 12, pp. 32-50.

- Mamonov M.O., Solntsev O. Otsenka vliyaniya veroyatnogo kreditnogo szhatiya na ekonomicheskuyu dinamiku i ustoichivost’ bankovskogo sektora: doklad na Gaidarovskom forume -2015 “Rossiya i mir: novyi vector” . Moscow, 2015.

- Mirkin Ya.M. Finansovoe budushchee Rossii: ekstremumy, bumy, sistemnye riski . Moscow: GELEOS Publishing House; Kepital Treid Kompani, 2011. 480 p.

- Moiseev S.R. Novaya makroekonomicheskaya teoriya otkrytoi ekonomiki . Den’gi i kredit , 2016, no. 1, pp. 18-25.

- Nametkin D.N., Safina N.Yu. Ob osnovnykh problemakh finansovoi stabil’nosti . Den’gi i kredit , 2016, no. 1, pp. 41-44.

- Pozdyshev V.A. Bankovskoe regulirovanie v 2015-2016 godakh: osnovnye izmeneniya i perspektivy . Den’gi i kredit , 2015, no. 12, pp. 3-8.

- Sadkov V.G., Grekov I.E. O vozdeistvii urovnya monetizatsii ekonomiki i struktury denezhnoi massy na effektivnost’ sotsial’no-ekonomicheskogo razvitiya . Finansy i kredit , 2004, no. 5 (143), pp. 43-46.

- Glazyev S.Yu. O neotlozhnykh merakh po ukrepleniyu ekonomicheskoi bezopasnosti Rossii i vyvodu rossiiskoi ekonomiki na traektoriyu operezhayushchego razvitiya: doklad . Moscow: In-t ekonomicheskikh strategii, Russkii biograficheskii in-t, 2015. 60 p.

- Po voprosu monetizatsii. Otvet Ministerstva ekonomicheskogo razvitiya Rossii . Available at: http://economy.gov.ru/minec/references/faq/201601110450

- McLoughlin C., Kinoshita N. Monetization in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. IMF Working Paper. WP/12/160.