Current trends in the traditional nature management of indigenous peoples of Siberia (the case of the Republic of Khakassia)

Автор: Panikarova Svetlana Viktorovna, Vlasov Maksim Vladislavovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Environmental economics

Статья в выпуске: 2 (26) т.6, 2013 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article is based on the results of the author’s empirical research exploring the characteristics of the traditional nature management of indigenous peoples of Siberia. The article proposes the mechanisms of implementing the potential of traditional nature management and provides recommendations for enhancing the efficiency of this type of economic activity in the case of the Republic of Khakassia.

Traditional nature management, regional development, indigenous peoples

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223446

IDR: 147223446 | УДК: 338.4:745(043)

Текст научной статьи Current trends in the traditional nature management of indigenous peoples of Siberia (the case of the Republic of Khakassia)

The main scientific research programmes in the field of nature management in the USSR in the 1917 – 1990 period were aimed at revealing the resource and raw materials potential of its territories; as for the study of traditional nature management of indigenous peoples, it was carried out on a purely voluntary basis. At the same time, this issue was studied intensively in the U.S. and European science centres. In this respect, the unexplored issues concerning the traditional nature management of indigenous peoples are becoming especially significant.

The present work is aimed at the development of the mechanisms implementing the potential of traditional nature management of indigenous peoples of Southern Siberia on the basis of the empirical study devoted to modern trends of nature management of the Khakass people.

In the early 1990s, the Russian Federation officially recognized and provided a legislative framework for the concept “traditional nature management of indigenous small-numbered peoples and ethnic groups of the North”, which is defined as a system of activities, formed throughout a centuries-old ethnic adaptation of ethnic groups to the natural and economic conditions of the territory; this system is oriented, in the first place, toward the maintenance of stability in the lifestyle and the type of nature management by an inexhaustible use and reproduction of natural resources for the benefit of the self-sufficient ethno-cultural existence of indigenous peoples [1]. The main functions of traditional nature management include food self-sufficiency, employment, increase in incomes, preservation of culture and the traditional way of life, preservation of biodiversity and productivity of the territory. In the future, this concept is reduced to “the traditional nature management of indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East”.

The situation concerning indigenous small-numbered peoples has changed for the better after the formation of a legal framework, implementation of government programmes on socio-economic development, the emergence of the network of organizations of the indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East, financed by international funds [8].

The question arises, why the Russian legislation highlights only the traditional nature management of indigenous small-numbered peoples and ignores the problems of economic management of indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East that do not have the status of small-numbered. According to the authors, the issues of social and economic disadvantages emerging on the territories of residence of indigenous peoples, including the ‘titular’ ethnic groups of the certain Russia’s subjects, require special approaches to their solution, particularly, in the sphere of nature management.

The territory of Southern Siberia is an ancient centre where the traditional complexes of extractive sector were formed. The Khakasses, as well as other Turkic peoples living on this territory, were originally engaged in hunting, fishing and harvesting of taiga resources, and they adapted to the peculiarities of the environment very well. Traditional nature management was an important part of their economic and cultural complex, and the product obtained as a result of fishing activities contributed substantially to the welfare of cattle-breeders. By the end of the 19th century, the revenue from cattle breeding in the Khakassia government agencies amounted to 82.5%, from agriculture – to 15.9%, from traditional nature management – to 1.6% [13].

In the process of their centuries-old historical development, the Khakasses have created an original ethnic culture, related to their economic activities [7]. The notion of yulyus that was an important part of the Khakasses’ world view formed the basis for their nature management, regulating the rules, ways and methods of their crafts and trades in the past [2]. Yulyus was seen as a sort of ‘life’s baggage’ that man must use rationally and spend before passing away. The exploitation of available natural resources was also considered in the light of yulyus. Wasteful nature management caused the ‘dispersion’ of life force of an individual as well as all of his clan. To avoid this, the Khakasses diversified nature management strategies and created many taboos that helped to maintain the balanced state of the territory’s ecological system.

Up to the beginning of the 20th century, hunting occupied a significant place in the Khakasses’ economy. Before joining the Russian Empire, the Khakasses who lived in taiga areas were regarded as hunting tribes and paid tribute in fur ( yasak ). N.N. Kozmin writes: “The hunting tribes were being constantly hunted themselves almost to the same extent as they hunted their prey. They were conquered by some strong tribe and after being laid under tribute (becoming the tribe’s kishtyms ), they received only one good in return, which is given by the consciousness: the tribute should be carried, to one place, and that ordinarily they would not be oppressed and robbed from every side” [6]. In the pre-revolutionary period, according to the registers of the Krasnoyarsk chancery, each person paid from 1 to 6 sables, except for the locality of Kachinskaya Zemlitsa, where the biggest fee amounted to 5 sables. The skins of foxes, lynxes, wolves, wolverines, bears, beavers, otters, squirrels, elks were also accepted, as well as payments in cash, namely 1 ruble per sable or as much, as other furs were evaluated, based on their price, established in relation to sable [12].

Other significant types of nature management in the economy of the Khakasses included gathering, wild-hive beekeeping, gathering pine nuts. During the 19th – 20th centuries, nutgathering ways remained virtually the same. Pine nuts were gathered by a team argys, consisting of 2 to 6 people. From 150 to 700 kg of nuts were gathered per one household. The Khakasses also gathered honey. Wildhive beekeepers looked for beehives with the help of solonets lure. At present, bee farming is widespread in the Khakassian aals (traditional Khakassian rural settlements). Along with wild-hive beekeeping, gathering has also changed significantly. The Khakasses don’t dig out edible roots (yellow daylight, adder’s-spear, etc.) anymore. But they still gather wild leek, wild berries, and, under the influence of Russian culture, they gather forest mushrooms (mostly for sale).

The most important elements of the traditional economy of the indigenous peoples in Siberia started deteriorating in the post-revolutionary 1920s already, with the changes in the self-government system of the indigenous peoples and also during collectivization, when the main institution of nomadic cattle-breeders, the institution of private ownership of the cattle, was transformed. The settlement system, as well as the ways of transferring traditional knowledge, practical skills and spiritual values remained mostly the same. Nevertheless, they faced profound transformation in the 1950s – 1960s, when the inhabitants of economically unviable villages were resettled to the farm centres of integrated collective farms and state farms, the Russian language became the overall medium of instruction, and school education for village children often implied education in boarding schools. The industrial development of Siberia led to the development of the traditional economic complex at a different cultural, organizational and economic basis. In the Soviet period and up to the 1990s, due to the socio-economic and socio-political processes in the country (collectivization, settlement and development of wild land (‘the upturn of virgin soil’), establishment of collective farms and their conversion into state farms, development of heavy industry, etc.) the socio-economic development of Khakas-sian aals changed considerably. As a result, traditional nature management receded into the background and became a subsidiary occupation of many Khakasses.

At the end of the 1990s, due to the socioeconomic crisis in the country (decline of agriculture, mass unemployment in rural areas), a significant part of Khakasses, living in the pre-taiga zone of Khakassia, resumed their hunting, fishing and other traditional activities. The return to traditional nature management was facilitated partly by an increased market demand for forest products (pine nuts, furs, curatives, etc.), which contributed to the development of traditional economy of the Khakasses [7].

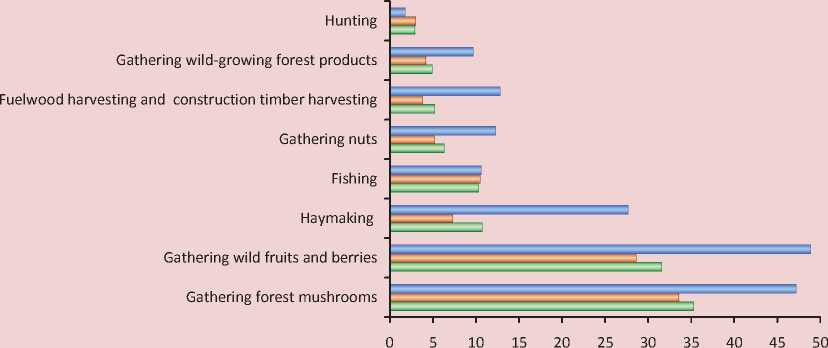

According to the results of empirical research (a survey of 1.500 households in 32 settlements of the region)1, we can conclude that modern households of the Khakasses are involved in traditional nature management to a greater extent than the Russian ones (fig. 1). It is evident that the Khakasses prefer almost all the kinds of activities on the use of forest resources (except for hunting and fishing).

Unfortunately, hunting that was once the field of specialization of Khakasses’ traditional economy, is facing serious problems in the Republic of Khakassia and in the whole country as well. The reasons for this difficult situation are of a complex nature, but experts claim that the main reasons can be found in the wrong government decisions.

According to V.I. Kenikstul’s assessment, all the various reorganizations of the state authorities of hunting sector management since 1990 have negative consequences, mostly. The ill-conceived ‘reforms’ undermined the hunting sector management and control system that had been developing for decades; they also damaged the system of state accounting, monitoring and regulation of the use of hunting animals. The elimination of the regional hunting administrations made it impossible to carry out federal target censuring of hunted animals. The activities of federal reserves have been terminated, their staff dismissed and their property lost. The officials of the state hunting inspectorate lost their independence and their right to keep and use arms, special equipment, etc. [5].

As a result, the planned quotas on the hunting of wild animals are not reached. For example, the percentage of achieving the

Figure 1. Traditional nature management in the Republic of Khakassia for the households’ own use

□ % of the number of respondents, total z % of the surveyed Russians z % of the surveyed Khakasses

planned quota of hunting resources in Khakassia in 2011 – 2012 amounted to: 35.6% for maral, 7.7% for wild boar, 17.8% for brown bears, 56.2% for sable, 4.9% for badger. The low degree of development of the quota reduces the state budget revenues and poses a threat to the environment and animal husbandry. For example, wolf population in Khakassia has increased sharply, and it is one of the strongest factors of the negative impact on hoofed animals. In hunting areas, where these carnivores are not exterminated, they can destroy up to 10% a year and more resources of wild hoofed animals, which exceeds the established annual hunting limits. The total number of wolf population in the Republic of Khakassia, judging by the winter route censuses, increases 2-fold annually, and the number of wolf attacks on farm animals increases, respectively.

Economic efficiency of the hunting economy in the Siberian regions can be estimated by comparing the revenues from the hunting economy per 1 hectare of fixed hunting lands (tab. 1) .

In the Siberian Federal District there are several regions, where the annual revenues per 1 ha of hunting areas exceed the district average. These regions include Altai Krai, the Kemerovo Oblast, the Novosibirsk Oblast, the Omsk Oblast, Krasnoyarsk Krai. Several regions, such as the Republic of Buryatia, the Republic of Khakassia, the Republic of Tyva, Zabaykalsky Krai have relatively low revenues per ha of hunting areas. Significant differences in economic efficiency can be explained, besides objective factors, by the broad powers of the RF subjects in regulation of hunting sector. Consequently, the institutions of hunting economy and their efficiency vary considerably in different regions.

The total area of hunting lands in the Republic of Khakassia is 5589.7 thousand hectares, out of which 3875 thousand are accessible to public. According to the State Committee for wildlife and environment conservation of the Republic of Khakassia, there are over 9 thousand hunters and 22 wildlife managers (a legal entity or an individual entrepreneur carrying out hunting-related economic activities).

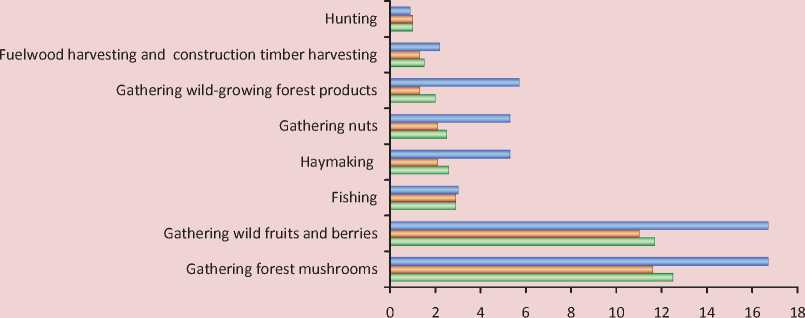

By all the types of traditional nature management, except for hunting and fishing, the potential marketability of traditional nature management products of Khakassia households is higher than that of the households on average: 16.3% of respondent Khakasses have opportunities to sell forest mushrooms (an average of 12.1% of households), 15.9% – wild fruit and berries (an average of 11.1% of households), and 4.9% – nuts (an average of 1.6% of households), etc. (fig. 2) .

Table 1. Revenues from the hunting economy (rubles per hectare)

|

Region |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

|

Siberian Federal District |

0.46 |

0.59 |

0.82 |

1.29 |

1.29 |

|

Altai Republic |

Data not available |

0.02 |

2.14 |

1.54 |

Data not available |

|

Republic of Buryatia |

0.12 |

0.15 |

0.19 |

0.30 |

0.29 |

|

Republic of Tyva |

0.48 |

0.68 |

0.38 |

1.09 |

0.74 |

|

Republic of Khakassia |

0.06 |

0.88 |

0.36 |

0.27 |

0.97 |

|

Altai Krai |

1.45 |

0.92 |

1.02 |

1.51 |

1.97 |

|

Zabaykalsky Krai |

0.50 |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.76 |

1.08 |

|

Krasnoyarsk Krai |

0.12 |

0.26 |

1.57 |

2.88 |

2.11 |

|

Irkutsk Oblast |

0.67 |

0.88 |

0.85 |

0.96 |

1.07 |

|

Kemerovo Oblast |

0.10 |

0.88 |

1.52 |

2.44 |

2.33 |

|

Novosibirsk Oblast |

0.91 |

1.49 |

2.32 |

2.81 |

2.64 |

|

Omsk Oblast |

0.98 |

1.51 |

2.53 |

2.86 |

3.30 |

|

Tomsk Oblast |

0.11 |

0.30 |

0.17 |

Data not available |

Figure 2. Traditional nature management in the Republic of Khakassia for sale

□ % of the number of respondents, total 5 % of the surveyed Russians Z % of the surveyed Khakasses

Table 2. Abandonment of traditional natural management of the households in the Republic of Khakassia

|

Activity |

% of the number of respondents |

||

|

Total |

Russians |

Khakasses |

|

|

Fishing |

8.70 |

8.09 |

10.90 |

|

Hunting |

2.39 |

2.49 |

3.54 |

|

Gathering forest mushrooms |

22.83 |

23.65 |

16.89 |

|

Gathering wild fruits and berries |

22.39 |

23.24 |

16.89 |

|

Gathering wild-growing forest products |

5.87 |

5.81 |

8.45 |

|

Gathering nuts |

10.87 |

10.79 |

13.35 |

|

Haymaking |

22.39 |

22.41 |

17.98 |

|

Fuelwood harvesting and construction timber harvesting |

4.57 |

3.53 |

11.99 |

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Table 2 shows the distribution of answers to the question: what type of traditional nature management the household was engaged in, though at present it quitted for a certain reason. Khakassia households are much less likely to abandon gathering wild mushrooms, wild fruits and berries and forest harvesting, than households on average, and they more often quit fuelwood harvesting and construction timber harvesting.

Besides, the respondents were asked what other activities, presented in the list, they would like to be engaged in (or take up, if they haven’t been engaged in any activity stated in the list), in addition to the main work, for consumption within the household.

The distribution of answers is presented in table 3 . The preferences of Khakassia houhesolds are higher for almost all the kinds of traditional nature management except for gathering forest mushrooms (historically Khakasses did not gather and process forest mushrooms).

The traditional knowledge of Khakassia households, which was formed through many generations, still plays a significant role in modern economic conditions. Work performance in Khakassian individual households is higher (in comparison to the average indicators for individual households) in such activities as gathering wild crop and pine nuts (tab. 4) .

Table 3. Potential of traditional nature management

|

Types of traditional nature management |

% of the number of respondents |

||

|

Total |

% of Russians |

% of Khakasses |

|

|

Fishing |

11.66% |

11.96% |

9.14% |

|

Hunting |

4.48% |

4.31% |

3.83% |

|

Gathering forest mushrooms |

28.25% |

31.58% |

19.47% |

|

Gathering wild fruits and berries |

28.25% |

29.67% |

24.78% |

|

Gathering wild-growing forest products |

4.48% |

3.83% |

6.49% |

|

Gathering nuts |

8.52% |

8.13% |

10.32% |

|

Haymaking |

9.42% |

7.18% |

16.81% |

|

Fuelwood harvesting and construction timber harvesting |

4.93% |

3.35% |

9.14% |

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Table 4. Work performance in household of Khakassia*

|

Activity |

Private households of the region on average (rub./h per person) |

Khakass households (rub./h per person) |

|

Gathering forest mushrooms |

47.6 |

47.6 |

|

Gathering wild fruits and berries |

84.1 |

89.8 |

|

Gathering wild crop |

186.9 |

246.8 |

|

Gathering pine nuts |

182.4 |

194 |

|

* In purchase prices of 2011. |

||

Thus, the system of traditional nature management of Khakasses comprises the peculiarities of the region’s socio-economic development and the features of Khakasses’ traditional culture. The indigenous population of Khakassia has preserved traditional forms of nature management, besides the people still widely use their traditional knowledge as well. The Khakassian households are involved in traditional nature management to a greater extent in virtually all the types of activities (except for hunting and fishing), and, just as important, the marketability of Khakasses’ traditional nature management is considerably higher.

The enhancement of economic efficiency of traditional nature management depends in many respects on the institutional structure [3, 11] and development of the territory where indigenous peoples live [4, 9, 10]. Besides, in order to implement the potential of traditional nature management of indigenous peoples of Siberia, it is appropriate to apply the following measures:

– to expand the range of products with those having useful properties. This, in turn, requires special studies on the assessment of the region’s resource base and useful properties of harvested resources (for example, on the content of vitamins, antioxidants, etc.).

– to carry out marketing studies of pilot batches of products for estimating the buyers’ attitude toward them, to improve the quality and range of products.

In the study, the authors make the following conclusions.

First, the Russian law actually limits the right of the indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East to practice traditional economic activities. Thereby, no attention is paid to the issues of social and economic ill-being of the territories where the indigenous peoples, who do not have the status of ‘small-numbered’, live. Their rights to self-organization and self-government are ignored as well.

Secondly, the indigenous population of Khakassia has preserved traditional forms of nature management (except for hunting and fishing). The marketability of Khakasses’ traditional nature management is considerably higher in all the kinds of activities, which indicates that the territories, where the indigenous peoples live, possess significant development potential.

Thirdly, using the obtained empirical data, the authors propose the mechanisms for the efficient implementation of the potential of traditional nature management of indigenous peoples of Siberia.

Список литературы Current trends in the traditional nature management of indigenous peoples of Siberia (the case of the Republic of Khakassia)

- Bocharnikov V.N., Bocharnikova T.B. Socio-economic aspects of development of the basins of the Samarga and Yedinka rivers. Sikhote-Alin: conservation and sustainable development of the unique ecosystem. Materials of the scientific and practical conference held September 4 -8, 1997. Vladivostok, 1997. P. 28-30.

- Burnakov V.A. Concept of yulyus and ecological traditions of the Khakasses. Traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples of the Altai-Sayan in the sphere of nature management: materials of the All-Russian scientific and practical conference, Barnaul, 11 -13 May, 2009. Ed. by I.I. Nazarov. Barnaul: Publishing house ‘ARТIКА’, 2009.

- Vlasov M.V. Strategy of production of new knowledge. Social sciences and modernity. 2007. No 3. P. 18-22.

- Vlasov M.V., Veretennikova A.Yu. The content of a current economic institute. Journal of economic theory (the Ural Branch of RAS). 2011. No. 4. P. 33-45.

- Kenikstul V.I., Yermakov A.A. On the improvement of hunting economy management system. APK: ekonomika, upravleniye. 2009. No. 10.

- Kozmin N.N. The Khakasses. Historical-ethnographic and economic essay. Irkutsk, 1925. P. 6.

- Kyrzhinakov A.A. Taiga occupations of the Khakasses in the 19th -20th centuries. Ph.D. in History thesis summary. Abakan, 2005.

- Maksimov A.A. About the revival of traditional economy forms in rural settlements of the Komi Republic. Ekonomika regiona. 2008. No. 1. P. 30-38

- Panikarova S.V., Vlasov M.V. Assessment of economic potential of region farms (on example of the Republic of Khakassia). National interests: priorities and security. 2012. No. 25. P. 25-32.

- Panikarova S.V., Vlasov M.V. Business in the sphere of national crafts as the most important component of ethno-economy (on the example of the Republic of Khakassia). Regional economy: theory and practice. 2012. No. 15. P. 40-48.

- Panikarova S.V., Vlasov M.V., Chebodayev V.P. Institutes of development in ethno-economics. Problems of modern economy. 2011. No. 4. P. 54-58.

- Pokrovskiy N.N. History of Siberia. Primary sources. Vol. 6. Siberia of the 18th century in the journeys of G.F. Miller. Novosibirsk, 1996. P. 69.

- Yarilova A.A. Manuscript Fund of Khakassian Research Institute of Language, Literature and History. No. 712.