Development of marriage and family relationships in the northern regions of Russia

Автор: Popova Larisa Alekseevna, Barashkova Anastasiya Spiridonovna

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 4 (34) т.7, 2014 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article deals with the mechanism of modern demographic development in Russia’s northern regions. The article studies the dynamics of marriage processes in the North in the post-war period, and reveals the current specifics of marriage and family relations. The authors analyze in more detail the situation in the two big northern republics: the Komi Republic and the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). They identify factors that determined a significant decrease of marriage rate in the 1990s and the relative normalization of marital and family processes in recent years. The article outlines the main directions of demographic policies in the northern regions.

Northern regions, population reproduction, marriage and family relations, level andstructure of nuptiality, demographic policy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223613

IDR: 147223613 | УДК: 314.5/.6(470-17) | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2014.4.34.11

Текст научной статьи Development of marriage and family relationships in the northern regions of Russia

Demographic studies pay great attention to the processes of fertility and mortality. At the same time, the research into the development of matrimonial relations is also an integral part of the demographic analysis: family circulation is included in a broad interpretation of the concept “reproduction of the population”. The presence of certain forms of marriage and family, and consequently, relations between men and women, between spouses, between parents and children provides stability to the process of human reproduction and its continuous renewal [1, p. 100].

What is more, all demographic processes are interconnected and interdependent. The trends to develop marriage and family relations influence not only fertility, but also mortality and the extent of migration mobility of the population.

In the midst of the protracted demographic crisis, from which the country is only just emerging, but already anticipating a structural reduction in the birth rate, the study of modern regional specificity of mating behavior of the population is of undoubted interest.

This article considers the features of matrimonial relations in the northern regions of Russia (the areas of the Far North and equated localities). It pays special attention to two large national republics of Komi and Sakha (Yakutia), which, on the one hand, are characterized by a number of common patterns of demographic development in the North and, on the other hand, are different in their own specificity, mostly due to the ethnic composition of the population and the degree of completion of the demographic transition in the titular ethnic groups.

The current patterns of demographic development in the North are the following: significant amounts of the population decline due to large-scale migration outflows over the past two and a half decades, and, consequently, higher paces of ageing of yet younger population of the North [2].

The natural movement of the population in the northern territories should be also assessed, despite the apparent relative success, reflected directly in the dynamics of the natural increase indicator in these regions during the demographic crisis period. In some northern regions the natural population loss began later than in Russia in general and ended earlier. For example, in the Komi Republic the natural decline was first observed in 1993, a year later than in the country. And in 2011, on the contrary, one year earlier than in Russia, the republic was the first to witness a positive natural increase, in urban areas – even in 2008. At the same time, in the depopulated northern regions, the total rate of natural decline, as a rule, was significantly less than the average, with the only exception being the Republic of Karelia and the Arkhangelsk Oblast.

In some Northern regions only certain territories experienced natural decline over time. For example, in the Sakha (Yakutia)

Republic depopulation was first recorded in 1993 in Aldansky District and in 1995 in Ust-Maysky District. In 2006 eight districts out of 35 experienced the decline [3].

What is more, some northern regions had a stable natural increase during the depopulation period in Russia. They were the following: Nenets Autonomous Okrug of the Arkhangelsk Oblast in the Northwestern Federal District; Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous okrugs in the Ural Federal District; the Tuva Republic in the Siberian Federal District1; the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic as a whole, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug and Kamchatka Krai (since 2007) in the Far Eastern Federal District. In Usinsk Urban Okrug of the Komi Republic there was natural growth during the whole period of depopulation.

There are several reasons for such processes. First, it is a younger age structure of the population (table 1), characteristic of the North. Its maintenance in the conditions of the long-term negative migration balance is caused not only by age potential of the population, accumulated due to longterm migration inflows, and by inflow and outflow of different age groups threads and also by relatively high levels of fertility of the indigenous peoples of the North. Ceteris paribus, the young age structure preconditions relatively high fertility and low mortality. Therefore, the increased amount of total mortality in the Republic of Karelia and the Arkhangelsk Oblast, also characterized by the young population structure, reveals a negative tendency. However, the Republic of Karelia since 2003 has had different and low total fertility rate, i.e. the significant decrease in the period of depopulation has been predetermined by mortality and fertility.

Secondly , the higher level of fertility is characteristic of the majority of indigenous Northern Peoples due to the incomplete demographic transition: almost all regions with a positive natural increase are autonomies with a noticeable percentage of the indigenous peoples of the North.

Thirdly , it is “export of mortality” from the North to southern regions. To the greatest extent, it is characteristic of territories with the resource-orientated economy. It leads to the increased life expectancy of the population of Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous okrugs, as well as Usinsky District of the Komi Republic.

These rates are ensured both by the low mortality rate from endogenous causes among men of working age due to significant territorial rotation and by the low mortality rate among older people who often leave the North. In all other Northern regions the rates of life expectancy of the population are lower than in Russia as a whole.

Thus, the lower depth of the demographic crisis in the Russian North is a mere formality due to the young age structure of the population, incomplete demographic transition among the indigenous peoples of the North and “export of mortality” to southern regions. In fact, the demographic sphere in northern regions is more troubled.

Table 1. Share of the population under and of working age in the Northern regions of Russia, according to the population census, % [4; 5; 6]

|

Region |

1989 |

2002 |

2010 |

|||

|

Under working age |

Of working age |

Under working age |

Of working age |

Under working age |

Of working age |

|

|

Russian Federation |

24.5 |

57.0 |

18.1 |

61.3 |

16.2 |

61.6 |

|

European North |

||||||

|

Republic of Karelia |

25.6 |

58.4 |

18.0 |

62.9 |

16.0 |

61.2 |

|

Komi Republic |

28.0 |

62.1 |

19.8 |

66.1 |

17.7 |

64.7 |

|

Arkhangelsk Oblast |

26.6 |

58.0 |

18.7 |

62.7 |

16.7 |

61.6 |

|

including Nenets Autonomous Okrug |

30.9 |

61.4 |

25.4 |

63.0 |

22.7 |

63.0 |

|

Murmansk Oblast |

27.4 |

64.0 |

18.1 |

68.4 |

16.2 |

65.5 |

|

Asian North |

||||||

|

Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug |

33.2 |

63.3 |

22.8 |

70.4 |

20.4 |

69.0 |

|

Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug |

32.8 |

65.2 |

24.9 |

70.5 |

22.0 |

70.2 |

|

Tuva Republic |

37.3 |

54.9 |

33.9 |

59.8 |

30.5 |

59.7 |

|

Sakha (Yakutia)Republic |

32.5 |

61.0 |

26.5 |

63.5 |

23.3 |

64.0 |

|

Kamchatka Krai |

28.2 |

66.5 |

18.8 |

68.9 |

17.1 |

65.6 |

|

Magadan Oblast |

29.4 |

66.9 |

19.1 |

69.8 |

16.8 |

66.5 |

|

Sakhalin Oblast |

27.2 |

62.7 |

18.6 |

66.5 |

16.7 |

63.7 |

|

Chukotka Autonomous Okrug |

30.6 |

67.5 |

23.2 |

70.1 |

22.4 |

67.3 |

The critical demographic problems of northern territories are the following: low life expectancy of the population, especially of men, and especially in rural areas; the young age structure of the dying and the significant proportion of mortality from external causes and diseases of exogenous etiology; low fertility rates in traditionally Russian northern regions and territories with the completed demographic transition among indigenous ethnic groups;

connection of the incomplete demographic transition among the indigenous peoples of the North with the adverse qualitative characteristics of fertility (particularly, with the significant percentage of non-marital births) and high levels of infant mortality [7].

Matrimonial relations in the North can be estimated as adverse. Due to a younger age structure, a high percentage of the working age population, which is also the age of marital activity, the northern regions have an increased crude marriage rate (tab. 2).

However, in some areas (for example, in the Komi Republic, Nenets Autonomous Okrug, the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic) the level of marriage rate is currently slightly higher than the Russian average, and it is often even lower.

In the Republic of Karelia and the Arkhangelsk Oblast the crude marriage rate is consistently below the national average rate. In the Tuva Republic its value is significantly lower than the national average level. On the one hand, it is caused by the fact that, unlike other territories of the Far North and equated localities, the young age

Table 2. Dynamics of the crude marriage rate of the population of the RF Northern territories in 2000–2011, marriages per 1000 persons [9; 10]

|

Region |

Year |

|||||||||||

|

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

|

|

Russian Federation |

6.2 |

6.9 |

7.1 |

7.6 |

6.8 |

7.5 |

7.8 |

8.9 |

8.3 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

9 |

|

European North |

||||||||||||

|

Republic of Karelia |

6.0 |

6.4 |

6.8 |

7.0 |

6.7 |

7.2 |

7.7 |

8.4 |

8.5 |

8.3 |

8.8 |

9 |

|

Komi Republic |

5.7 |

7.3 |

7.3 |

7.7 |

6.2 |

7.5 |

7.7 |

8.7 |

8.0 |

8.6 |

9.0 |

10 |

|

Arkhangelsk Oblast |

5.2 |

6.4 |

6.6 |

7.3 |

6.0 |

7.5 |

7.6 |

8.9 |

7.9 |

8.4 |

8.9 |

9 |

|

including |

||||||||||||

|

Nenets Autonomous Okrug |

6.2 |

7.0 |

7.3 |

6.9 |

5.1 |

6.3 |

7.6 |

8.9 |

8.4 |

8.0 |

8.1 |

8 |

|

Murmansk Oblast |

7.0 |

7.9 |

7.9 |

8.7 |

7.4 |

8.4 |

8.5 |

9.3 |

8.6 |

8.9 |

9.3 |

9 |

|

Asian North |

||||||||||||

|

Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug |

8.7 |

10.8 |

10.4 |

10.0 |

8.4 |

9.7 |

10.5 |

11.5 |

10.6 |

10.7 |

11.3 |

12 |

|

Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug |

8.4 |

9.9 |

9.9 |

10.1 |

8.6 |

9.2 |

8.9 |

10.1 |

8.8 |

9.4 |

9.8 |

10 |

|

Tuva Republic |

3.7 |

4.9 |

5.4 |

6.6 |

5.2 |

5.3 |

5.6 |

8.7 |

8.7 |

8.5 |

6.8 |

7 |

|

Sakha (Yakutia) Republic |

6.1 |

7.7 |

7.8 |

8.2 |

6.8 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

8.4 |

7.8 |

8.5 |

8.7 |

9 |

|

Kamchatka Krai |

7.1 |

8.0 |

8.5 |

8.7 |

7.5 |

8.9 |

9.0 |

9.6 |

9.5 |

10.1 |

10.3 |

10 |

|

Magadan Oblast |

7.4 |

8.3 |

8.9 |

9.0 |

7.4 |

8.8 |

9.1 |

10.0 |

9.8 |

9.5 |

9.6 |

10 |

|

Sakhalin Oblast |

6.2 |

6.9 |

7.6 |

8.0 |

7.2 |

8.2 |

8.8 |

9.7 |

9.6 |

9.7 |

9.9 |

9 |

|

Chukotka Krai |

6.9 |

7.8 |

9.7 |

9.3 |

9.5 |

10.0 |

9.7 |

10.0 |

9.7 |

10.1 |

9.1 |

7 |

structure of the Tuva population (with a high percentage of children ages) is characterized by a relatively low, below the national average proportion of the working age population (see table 1). But, in addition, the low crude marriage rate correlates with a high percentage of non-marital births that is more than twice higher than the national average level and with a low level of crude divorce rates. It is obvious that this region has very strong features of matrimonial relations of the indigenous population that have a negative impact on the level of official regulation of marriage rates.

The trends in marriage processes in the northern regions are close enough to the national average; still there is some time lag.

The national average decline in the marriage rate began almost immediately after the war, after a significant, but very short compensatory rise.

In 1946, the crude marriage rate of the Russian population doubled the pre-war value; however, in the conditions of significant postwar gender imbalance, the marriage processes experienced a decline since the following year [8, p. 18-20].

This time there was a fundamentally different situation in the northern regions. Already in the pre-war period the need to attract natural resources in the economic turnover had led to the influx of population to the North.

However, in the first postwar decade the amount of migration growth was unprecedented. As the majority of migrants were young, mostly unmarried men, the migration improved the age-gender and marital structure of the population in the northern territories significantly, setting apart from the current situation in the country.

In the Komi Republic, for instance, in 1945 the crude marriage rate was also more than two times higher than in the prewar 1940 – 10.7 and 4.6 per 1000 persons, respectively. However, it continued to rise at a rather high rate during the first postwar decade.

The most significant growth was in the first half of the 1950s, when there was a maximum migration rate in the republic. Having reached the peak (28.4‰ in 1955), apparently, due to “Komsomol” weddings in the regions of new development, the marriage rate in the Komi Republic began to decline gradually. For three decades this trend was slow and gradual, changing only at certain periods, primarily due to unfavorable changes in the age structure of the population. So, the small number of people, born during the war, and the migration outflow resulted in low values of the crude marriage rate of the population in the Komi Republic in the 1960s – early 1970s.

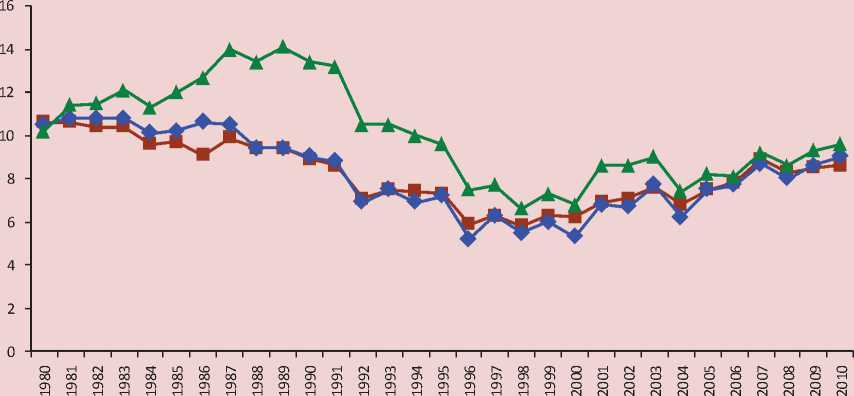

Obviously, the same was true for the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, as by the early 1980s the values of the crude marriage rate in these republics had almost equaled to the national level (fig. 1) . The relatively young age structure of the population of the considered regions indicates a greater problem of the development of the official marriage and family relations during this period.

The first half of the 1980s in the Northern regions observed some improvement in marital processes, especially, the Sakha

Figure 1. Dynamics of the crude marriage rate of the population in the Russian Federation, the Komi Republic and the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic in 1980–2011, marriages per 1000 persons

— ■ — Russian Federation t Komi Republic * Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)

(Yakutia) Republic where in 1980–1987 the increase of the crude marriage rate amounted to 37.3%. Apparently, this was a consequence of the 1981 Regulation “On measures to strengthen support for families with children” [11], which played a prominent role in the normalization of the demographic situation in the country in the first half of the 1980s, especially in the regions with higher fertility rates.

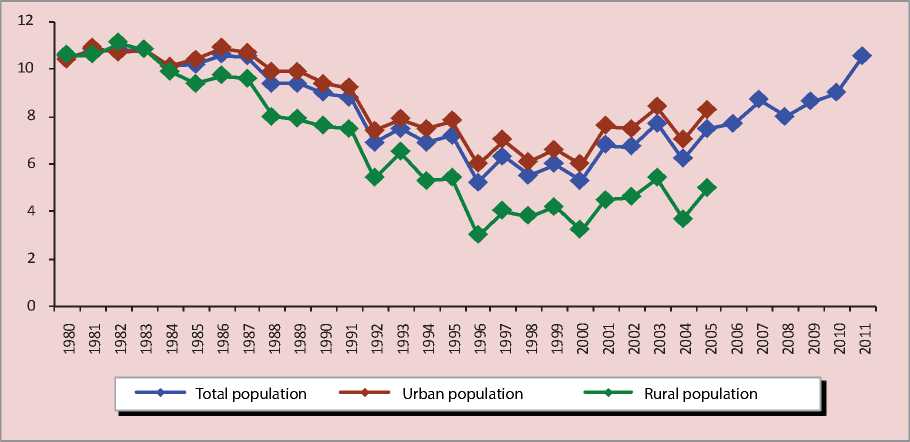

There was no noticeable growth in the marriage rate in the Komi Republic; there was rather stabilization of its level. Although it should be noted that in 1981–1983 the republic had the highest indicators since the mid-1960s (10.8 marriages per 1000 persons). What is more, almost till 1991 the crude marriage rate in the republic exceeded the all-Russian level. However, in the second half of the 1980s, the decline rate in its level in the Komi Republic increased significantly (fig. 2).

The main reason, like two decades ago, was a decrease in the share of the population of the marriageable age due to the low birth rate of the 1960–1970s and another migration outflow. And at the end of the 1980s marital processes were influenced by changing standards of marriage and family behavior due to sexual revolution, which had been popular in the West two decades ago. Democratization of social norms, regulating gender relations, led to a gradual shift from traditional marriage and family norms, causing earlier sex life,

Figure 2. Dynamics of the crude marriage rate in the Komi Republic in 1980–2011, marriages per 1000 persons

widespread premarital sexual relations, trial and de facto marriages, the increase in the number of marriages caused by out of wedlock pregnancy, the increase in the share of non-marital births occurring in de facto marital unions and in single-parent families, Besides, people started to marry and have children earlier.

Due to a younger age structure of the marriage rate half of men under 24 got married in the early 1990s. One should pay attention to quite a significant increase in the marriage rate of rural men of 20–24 years in the republic during this period. It indicates normalization of marriage processes in rural areas due to mitigation of the problem “shortage of brides”. Significant outnumber of men of the age of the maximum marriage rate complicates their activity on the marriage market.

Therefore, the female indicators of the marriage rate in the Komi Republic are traditionally higher than the male ones, especially in rural areas.

However, during the 1980s and early 1990s there was noticeable improvement in gender proportions in the most active marriageable ages: if in 1981 there were 63 women per 100 men of 20–29 in rural areas, after 10 years there already 76 women. As a result, at the beginning of 1990s the Komi Republic observed a significant reduction in the difference between the levels of the marriage rate of rural men and women. Mitigation of gender disparities in the age of maximum marriage activity, leading to the convergence of male and female marriage potentials, further continued. So, ten years later in 2001 there were 89 women per 100 rural male of 20–29 years.

However, the early 1990s experienced the significant decrease in the level of the marriage potential fulfilment due to severe deterioration of the socio-economic situation. Therefore, men failed to take full advantage of the improved gender ratio on the marriage market.

The dramatic decline in living standards due to the crisis in the reforming Russian economy resulted in postponement of demographic events in the early 1990s. It should be noted that the marriage rate is the least subject to significant changes of external conditions. Its level is greatly influenced by conflicts and crises. Therefore, almost instantly the marriage processes reacted to the deteriorated socio-economic situation: in 1992 the reduction in its level everywhere had a disastrous nature. At the same time, in the postwar period the level of the crude marriage rate of the population in the Komi Republic exceeded the national average due to the younger age structure of the population; since 1992 it has become stably lower than the all-Russian level, despite the fact that the age structure of the population has still been relatively young.

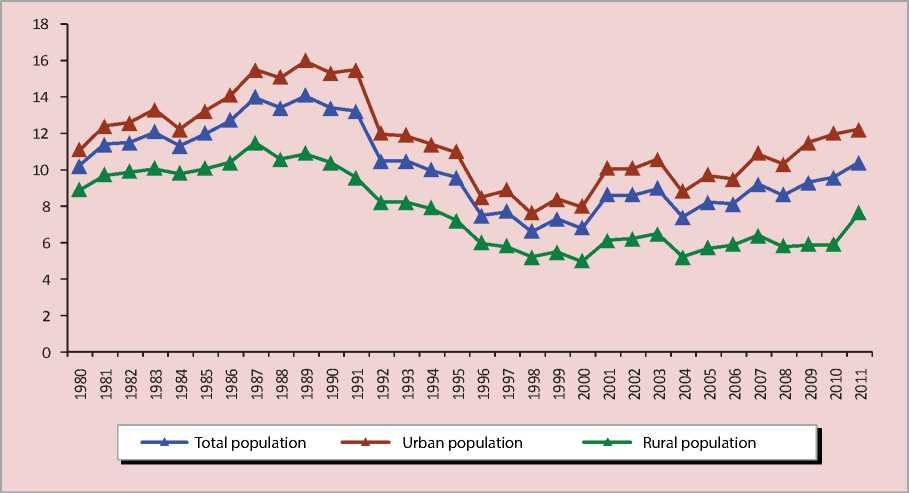

In the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic the marriage rate, having increased considerably during the 1980s, remained quite high almost till 1991. However, it fell sharply since the beginning of socio-economic reforms. In 1992 the crude marriage rate decreased by 20.5%. In 1991–1996 the decline amounted to 43.2%; in 1998, with the minimum crude marriage rate being recorded (6.6 marriages per 1000 persons), there was a twofold decrease, compared to 1991 (fig. 3) .

The instability of the socio-economic situation and raising inflation forced many potential wedding couples to postpone the wedding. Evidently, the 1992 recession was largely associated with the inevitable decline in the marriage rate due to the leap year. May and the leap year are not popular for marriage among people. The year before a number of people get married in December not to start a family in a leap year.

However, the monthly number of marriages in 1992 discloses that the most significant reduction in the marriage activity occurred from April, when the marriages, planned already in 1992, were registered. At the same time, the figures show that the period in the marriage activity of the population in the Komi and Sakha (Yakutia) republics has been reduced by half since that time. The decline in the marriage rate is now observed not once in four years, and in each even-numbered year. In Russia as a whole the four-year period remained mostly unchanged.

In the 1990s the marriage rate level in the Komi Republic and the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic experienced fluctuations determined by the descending trend: each subsequent recession was deeper than the previous one and the increase became increasingly small. In the first decade of the economic reform (1992–2001) the average crude marriage rate in the Komi Republic was more than one third below the level of the previous decade (1982–1991). In rural areas of the republic it was reduced by half, in urban – by more than 30%. There was the same trend in the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic. In urban areas the decline

Figure 3. Dynamics of the crude marriage rate in the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic in 1980–2011, marriages per 1000 persons

was exactly the same as in the Komi Republic; in rural areas it was not as significant as in Komi (37%).

Another indicator of the reduced marriage potential of the population in the 1990s is the dynamics revealing the probability to get married by a certain age. It is calculated by summing the age-gender marriage rates by a certain age on the basis of a total demographic factor. Such calculations are only performed for the Komi Republic due to scarce data. At the 2001 marriage rate 76% of men and 81% of women could get married by the age of 50 (including remarriage), while in 1991 98% of men and 121% of women could. Unfortunately, the calculation of many demographic indicators after 1996 is impossible as Rosstat stopped to publish some demographic data (the list was expanded in 2006; Figure 2 clearly demonstrates it: crude marriage rates separately for urban and rural population in the Komi Republic have recently become unavailable for researchers). So, it is impossible to assess the reduction in the probability to marry for the first time in general during this decade.

However, this assessment can be carried out for the initial period of socio-economic reforms. In the Komi Republic in 1991 75% of men and 90% of women could marry for the fist time by the age of 50, while in the middle of the decade (1995) 64% of men and 68% women could. At the same time, since the beginning of the 1990s all odd-numbered years have been characterized by the increased marriage activity of the population, so the 2001 and 1995 indicators reflect not the most unfavorable situation of those years.

Marriage potential of the population is higher nowadays. The figures reveal that in the early 2000s in the Komi Republic, the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic and in the whole country, there was an increase in the marriage rate: the last decade demonstrated a clear increasing trend. Since 2004 the northern republics have been again characterized by the four-year period of marriage activity. At the end of the decade, the marriage rate in the Komi Republic was equal almost to the 1991 level, and in 2011 – to the 1987 level, close to the maximum level of the early 1980s. In the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic in 2011 the marriage rate equaled the 1992–1993 level, but the increase was also very noticeable. Apparently, in many respects this growth was a result of the improved age structure of marriage cohorts. Numerous generations, born in the middle and a second half of the 1980s, attained marriageable age. However, the state demographic initiatives to support family fertility have contributed enough in recent years.

Figure 2 shows that the crude marriage rate in the rural areas of the Komi Republic started to lag behind the urban ones significantly in the second half of the 1980s. In the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic where the marriage rate in the rural territories has been traditionally below the urban ones, in the second half of the 1980s this difference between urban and rural areas increased (fig. 3).

The low marriage rate in rural areas of the Komi Republic was mostly caused by significant ageing of the rural population. However, since 1994 the crude marriage rate in rural women has dropped even below the city level, which was the only rural indicator of the marriage rate, compared favorably with the urban. As it has been already mentioned, such a good indicator was based on very favorable gender ratio on the marriage market. “Shortage of brides”, existing in the rural areas of the republic, has traditionally determined both the reduced marriage rate of the male population and the increased one of the female.

Over the past three decades the gender ratio in rural areas of the Komi Republic has levelled off significantly, contributing to the convergence of male and female marriage potentials.

However, their realization decreased in the 1990s considerably. Despite the decline in the crude marriage rate and the total marriage rate of women below the urban level not only of the crude marriage rate, the first marriage rate of the rural population in the Komi Republic still remained above the urban. If in the urban areas 62% of men and 66% of women could marry for the first time in 1995, in the rural ones 69% of men and 74% of women could. Hence, rural people realized their marriage potential better. The higher marriage rate of the urban population was determined by the re-marriage rate, a consequence of the high divorce rate.

Thus, the situation with the official marriage rate in the rural areas could be considered more favorable than in the urban.

However, it is necessary to study a more significant reduction in the marriage rate among rural people. In our opinion, it can be considered as an indicator of changes in patterns of marriage and family behavior of the Russian population in the second half of the 1980s due to the spread of de facto marriages. De facto marriages, unlike extramarital sexual relations without stable family relationship that are more spread in the city, become more popular in the rural areas, and, especially, in the Komi Republic, where indigenous ethnic groups comprise more than a half of the rural population. They have had some specifics of marriage and family behavior, recognizing de facto marriages along with registered ones. It is obvious that de facto marriages came into wide practice in the second half of the 1980s–early 1990s in the village again as in the 1920–1930s. Later they became typical for the urban population, especially for re-marriages.

The lack of legal regulation of marital relations, traditionally more common for re-marriages had involved the spread of de facto marriages since the end of the 1980s. Till the early 1990s there was an increase in the share of re-marriages in all age groups except the youngest. This growth was especially vivid in the urban areas where for a long time the share of re-marriages in their total number had been one and a half – two times higher than their share in the rural areas. But since the early 1990s in the rural areas and since the middle of the decade in the urban areas the share of re-marriages declined and then stabilized. Only recently (in 2007–2008) this share has again grown in the overall structure of registered marriages. The increased government attention to demographic problems was encouraged by the Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly in 2006. As the great importance was attached to the normalization of matrimonial relations, registered marriages began to strengthen their positions again.

The important point is a ratio of remarriage rates among women and men. Usually men remarry more often than women. Researchers usually explain such psychological factors as women’s higher demands to a new partner if they have children from the first marriage, low competitiveness of women with children on the marriage market, etc. At the same time, insufficient attention is paid to gender proportions. However, apparently, more frequent re-marriages among men are caused by a greater number of women. In the Komi Republic gender disparity in favor of men results in a high value of brides of any marital status on the marriage market, that is why the above pattern has not been observed until recently.

But since the beginning of the 2000s in the conditions of significant alignment of gender proportions and numerical predominance of men in the most active breeding ages the share of re-marriage among men in the Komi Republic has exceeded the female rate. Obviously, women’s increased demands to a new husband with children and reduced competitiveness of women with children on the marriage market also play an important role in distribution of re-marriages among men and women.

As it has been already mentioned, in the late 1980s–early 1990s on the background of the indicators decrease in almost all age groups often people under 20 got married. However, in the first half of the 1990s this tendency came to an end.

So, in the Komi Republic the highest percentage of marriages among people under 18 was recorded in 1992 (1.2% of men and 6.3% of women), and among people under 24 in 1993 (53.8% and 64.2, respectively). Since 1994 the decrease in the average marriageable age in the Komi, the Sakha (Yakutia) republics and Russia, as a whole, changed in its growth. The increase in the share of marriages among people over 25 has been recently very vivid. Apparently, due to the government and society’s attention to the family issues people who have delayed their marriage for some reason get married nowadays. As a result, in 2009–2011 in the Komi Republic the share of marriages among men over 25 exceeded 72%, among women almost reached 60%.

On the other hand, taking into account that in most developed countries the reduction in the average marriageable age changed into its growth in the early 1970s after the sexual revolution, one may consider this as a natural long-term historical trend, which can involve a more significant reduction in the marriage rate and a further increase in the level of the single state. Apparently, people retreat from the traditional model of early marriage. The sexual life of young people begins earlier, and the marriageable age rises.

At the same time, public opinion is increasingly sympathetic to de facto marriages. Their number grows, putting aside registered marriages.

In other words, the recent increase in the average marriageable age, the significant lag of the rural marriage rate, stabilization (until recently) of the re-marriages share and the high share of non-marital births (about a half is registered at the joint request of the parents) reveal wide spread of de facto marriages. Quite significant orientation of young people on unregistered marriage, early premarital sexual relations on the background of the low contraceptive culture and contraceptive responsibility contribute to further strengthening of alternative forms of family organization.

Popularity of de facto marriages is confirmed by the comparison of the results of 1994, 2002 and 2010 censuses. So, during the second half of the 1990s and the early 2000s, the share of men of the marriageable age in a de facto marriage increased from 6.3% in 1994 to 8.7% in 2002 and to 12.6% in 2010, the share of women from 5.5 to 7.6% and to 10.7%, respectively [12, 13] in the Komi Republic.

It should be noted that in the Komi Republic the share of the population in de facto marriages was significantly above the national average of the same indicator. The de facto marriage rate of the Russian population in general even in 2002 was lower (6.1% of men and 5.1% of women over 16 who reported their marital status) than this rate the Komi Republic in the mid 1990s.

In Russia in 2010 the de facto marriage rate for men and women was 8.4 and 6.9%, respectively [6], that was lower than in the Komi Republic in 2002 In the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic the de facto marriage rate was also higher than in the whole country. The share of men in a de facto marriage increased in the republic in 2002–2010 from 8.0 to 10.6%, the share of women – from 7.3 to 9.6% [6, 12].

In addition, registered marriages are often preceded by either de facto marriages or premarital pregnancy, with it being more or less stable premarital relationships between future spouses. For a more detailed study of some aspects of the official marriage rate, not reflected in the current statistics, at the end of 2002 we conducted the study of all cases of marriage registration in 3 rural settlements of the Komi Republic in 1992–2001 [14]. The criterion to select these rural settlements was the possibility to get reliable retrospective information. In small communities, where everyone knows each other, additional information can be obtained from interviews with the experts, registering demographic events.

The study has showed that in the period under consideration at least in the rural areas of the Komi Republic the majority of registered marriages were preceded by de facto marriages of varying duration. More than 20% of marriages were registered after the birth of children. The great share of marriages was registered due to premarital pregnancy of the bride (30–45%). It is considered to be one of the factors of instable family life.

Besides, not all cases of non-marital births fall within the statistics of illegitimate births, which in the Komi Republic in 2011 was 32.7% of births and 41.8% in rural areas, even after six years of decline, i.e. the level of illegitimate birth was, in fact, even higher than that, reflected in the official statistics.

Regulation of de facto marriages often ends the process of demographic development of the family. The study has disclosed that in approximately 40% of marriages, registered during the decade, children were not born later: either they had been born by future spouses before marriage (more than 20% of marriages), or were not planned due to the age of spouses, the presence of children from previous marriages, etc. (almost 20% of marriages).

Thus, in the last two decades along with the officially regulated form of the family, de facto marriages have been widespread in Russia, with only part of them being registered later. This is true for the Komi and Sakha (Yakutia) republics to a greater extent. And even it is more characteristic of the Tuva Republic that has traditionally had low marriage rates and a very high level of extramarital fertility.

It is known that not only single-parent families but also de facto marriages are characterized by a smaller number of children in the family. Moreover, de facto marriages are less stable in terms of divorce rates: obstacles to the official registration of the relationship strengthen centrifugal tendencies in unstable unregistered marriage.

It predetermines lower fertility rates.

In other words, the family structure of the past two decades predetermines low birth rates.

The increased government attention to the problems in the demographic sphere in 2006–2007 led to betterment in the processes of officially registered marriages. In the early 2000s the growth in the marriage rate was caused by the improvement of the age structure of marriage cohorts in recent years, recently it has been intensified by “postponed marriages” – older age at marriage. The decline in the share of non-marital births since 2006 indicates the enhanced situation in this sphere.

This reveals that trends in the development of marriage and family relationships can have a positive impact. That is why it is necessary to promote the family values revival, expand measures to strengthen the institution of family and moral traditions of family relationships.

For northern regions of Russia the objective to consolidate the institution of the family, revive and deepen spiritual and moral traditions of family relationships is very important. Indeed, in many respects the crisis of family values and prevalence of extrafamilial interests are responsible for the low level of reproductive attitudes of the population, their insufficient implementation, and for the fact that fertility is becoming more and more “extrafamilial activity”. And in the northern regions these negative aspects are amplified due to more substantial disorganization of family life.

It is caused by large migration (non-indigenous and, especially, non-permanent population has lower levels of social control and self-control, that is why migrants increase likelihood of different kinds of deviations, including in the matrimonial sphere), and by some features of matrimonial behavior of indigenous peoples (residual effects of polygamy as in the Tuva Republic, traditionally loyal attitude to the illegitimate birth as in the Komi Republic, or disorganization of matrimonial relations on the basis of longterm marginalization of some indigenous peoples of the North).

To sum it up, we emphasize the critical demographic problems of the northern regions that require intensified regional measures of demographic policy.

-

• Almost all northern territories of Russia face a very acute problem of mortality, particularly, premature male mortality from external causes, especially, in rural areas. Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous okrugs are not an exception: life expectancy of the population there is also very far behind developed countries.

-

• In most northern territories of Russia it is necessary to significantly reduce infant mortality: in the republics of Tuva and Sakha (Yakutia), in Nenets, Yamalo-Nenets and Chukotka Autonomous okrugs, Kamchatka Krai, the Magadan and Sakhalin oblasts.

-

• In the Republic of Karelia, the Murmansk and Arkhangelsk oblasts it is highly relevant to improve fertility. In recent years, the quantitative aspects of fertility have become urgent in Kamchatka Krai and the Magadan Oblast.

-

• In the republics of Karelia, Komi, Sakha (Yakutia) and the Arkhangelsk Oblast attention should be paid to the promotion of marriage and births in a registered marriage.

-

• The extremely significant level of extra-marital fertility, correlated with high values of the infant mortality rate, characteristic of the Tuva Republic, Nenets and Chukotka Autonomous okrugs, Kamchatka Krai, the Magadan and Sakhalin oblasts challenges these regions to improve the quality of birth.

-

• In the Magadan Oblast, Chukotka and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous okrugs the issues to improve stability of the family are topical.

-

• In the Tuva Republic it would be better to strengthen moral traditions of family relations and improve official regulation of matrimonial processes.

In our opinion, for the regions of the Russian North the demographic policy objective should be defined as creation of conditions for sustainable and high quality development of the population, provision of stable natural growth based on the convergence of the life expectancy rate in the region with that in the country, enhancement and improvement of the quality structure of fertility, based on the strengthened moral traditions of family relationships.

Cited works

-

1. Volkov A.G. Family – the Object of Demography . M: Thought, 1986.

-

2. Popova L.A., Zorina E.N. Northern Version of the Russian Model of the Demographic Aging. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends and Forecast , 2013, no.2(26), pp. 111125.

-

3. Mostahova T., Veselkova I. Improving the Management of Demographic Processes in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Federalism , 2009, no.2, pp. 169-178.

-

4. Population Age Structure in RSFSR according to AllUnion Population Census in 1989. Moscow, 1990.

-

5. Age and Sexual Structure and Marriage Status. Results of the AllRussian Population Census in 2002: In 14 Volumes. Volume 2 . Federal State Statistics Service. Moscow, 2004.

-

6. National Census of 2010. Available at: http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/perepis_itogi1612 . htm (accessed May 31, 2013).

-

7. Popova L.A. Features of the demographic development of the Russian northern territories. Russia and the modern world , 2010, no.4. pp. 178190.

-

8. Sinelnikov A.B. Marriages and Fertility in the USSR . Moscow: Nauka, 1989.

-

9. Demographic Yearbook of the Komi Republic. 2010 . Syktyvkar, 2011. Pp. 166167.

-

10. The Central Statistical Database . Available at: http://cbsd.gks.ru/ (date accessed 31.05.2013).

-

11. Resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU, USSR Council of Ministers No. 235 of January 22, 1981 “On measures to strengthen public support for families with children”. C ollection of the USSR Resolutions , 1981, no.13, p.75.

-

12. Age and Sex and Marital Status. Results of the AllRussian Census in 2002: in 14 Volumes. Volume 2. Federal State Statistics Service. Moscow, 2004.

-

13. Marital Status and Education. The Results of the Population Census in 2010. Komi Republic. Volume 2: Statistical Collection. Komistat . Syktyvkar, 2012.

-

14. Popova L.A. Modern Features of the Formation and Development of the Family in the Komi Republic. Family in Russia: Scientific Social and Political Journal , 2006, no.1, pp. 2539.

Список литературы Development of marriage and family relationships in the northern regions of Russia

- Volkov A.G. Sem’ya -ob”ekt demografii . Moscow: Mysl’, 1986.

- Popova L.A., Zorina E.N. Severnyi variant rossiiskoi modeli demograficheskogo stareniya . Ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz , 2013, no.2(26), pp. 111-125.

- Mostakhova T., Veselkova I. Sovershenstvovanie upravleniya demograficheskimi protsessami v Respublike Sakha (Yakutiya) . Federalizm , 2009, no.2. pp. 169-178.

- Vozrastnoi sostav naseleniya RSFSR po dannym Vsesoyuznoi perepisi naseleniya 1989 g . Moscow, 1990.

- Vozrastno-polovoi sostav i sostoyanie v brake (Itogi Vserossiiskoi perepisi naseleniya 2002 g.: v 14 t. T. 2) . Feder. sluzhba gos. statistiki . Moscow, 2004.

- Vserossiiskaya perepis’ naseleniya 2010 . Available at: http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/perepis_itogi1612.htm (data obrashcheniya: 31.05.2013).

- Popova L.A. Osobennosti demograficheskogo razvitiya severnykh territorii Rossii . Rossiya i sovremennyi mir , 2010, no.4, pp 178-190.

- Sinel’nikov A.B. Brachnost’ i rozhdaemost’ v SSSR . Moscow: Nauka, 1989.

- Demograficheskii ezhegodnik Respubliki Komi. 2010 . Syktyvkar, 2011. Pp. 166-167.

- Tsentral’naya baza statisticheskikh dannykh . Available at: http://cbsd.gks.ru/(data obrashcheniya: 31.05.2013).

- Postanovlenie TsK KPSS, Sovmina SSSR № 235 ot 22 yanvarya 1981 g. “O merakh po usileniyu gosudarstvennoi pomoshchi sem’yam, imeyushchim detei” . SP SSSR , 1981, no.13, p.75.

- Vozrastno-polovoi sostav i sostoyanie v brake (Itogi Vserossiiskoi perepisi naseleniya 2002 g.: v 14 t. T. 2) . Feder. sluzhba gos. statistiki . Moscow, 2004.

- Sostoyanie v brake, obrazovanie. Itogi Vserossiiskoi perepisi naseleniya 2010 goda. Respublika Komi. Tom 2: stat. sb. . Komistat. Syktyvkar, 2012.

- Popova L.A. Sovremennye osobennosti formirovaniya i razvitiya sem’i v Respublike Komi . Sem’ya v Rossii: Nauch. obshchestv.-politich. zhurn. , 2006, no.1, pp. 25-39.