Economic integration of immigrants through overcoming inequalities in employment and wages. Comparative analysis of British and French Muslim communities

Автор: Moisa Natalya I.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Foreign experience

Статья в выпуске: 3 (63) т.12, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The issue of immigration management is one of the most complex and relevant both in academic science and practical politics. It polarizes public opinion and provokes fierce debate. One of the most important objective of the domestic policy of countries with a large number of immigrants is effective socio-economic integration of foreign cultural communities and consolidation of the civil society. The article deals with the general issues of integration of Muslim immigrants in the UK and France in the economy; provides data on their number, employment, income and social status compared with the ethnic majority. The information framework of the research includes official statistics, sociological surveys, analytics of government institutions and commissions, reports of well-known research centers and Muslim organizations. Due to the peculiarities of statistics it is impossible to directly compare the situation of British and French Muslims. Moreover, in the UK and France, migrant integration is carried out according to different historical models. The article demonstrates the specific features of each country in migrant resettlement, the position of Muslims in the labor market among various immigrant minorities, the issues of the national policy in fighting against discrimination and Islamophobia. The purpose of the article is to focus on objective quantitative and qualitative indicators of economic activity of Muslim immigrants in the two countries in question to overcome the existing stereotypes and political speculation. Analysis of the economic status of Muslims in the UK and France reveals a significant spread depending on the country of origin, country of birth, belonging to the first or the second generation of immigrants. The article concludes that the UK opens up more opportunities for the economic integration of Muslims than France.

Immigration, muslims, economic integration of immigrants, uk, france, employment, labor market

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147224177

IDR: 147224177 | УДК: 325.14 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2019.3.63.10

Текст научной статьи Economic integration of immigrants through overcoming inequalities in employment and wages. Comparative analysis of British and French Muslim communities

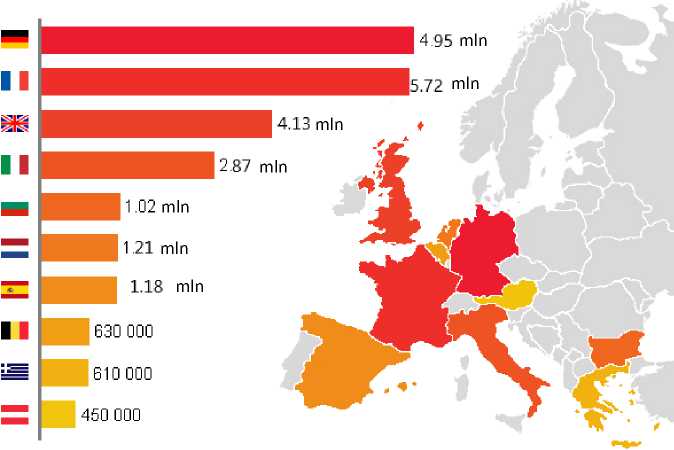

At the moment, Islam is the second largest and fastest growing religion in Europe. The number of Muslims is increasing three times faster than the growth of indigenous nonMuslim population. This is due to the record high immigration in the past 30 years and higher birth rate than in Christian or nonreligious families. The numbers ( Fig. 1 ) speak for themselves.

According to Pew Research Center, in 2016 the largest Muslim communities have developed in France, Germany, the UK, and Italy [1]. Germany is most often chosen as an asylum; traditional migrants prefer the UK. The rapid demographic growth of the Muslim community in Europe makes its rapid integration impossible. In countries of mass migration of Muslims the rejection among indigenous population is growing. Islamophobia is progressing; among all migrant communities, the most difficult is the integration of Muslims [2, pp. 3, 9]. The increase in the number of Muslims in Europe since the end of the 20th century has become a global challenge for the European civilization. The issue of the threat to national identity, the concept of the nation state is on the agenda. At the same time, it is equally important to maintain economic stability, a high standard of living in economically developed European countries, and therefore, search for effective mechanisms for migrant integration

Figure 1. Muslim population in European countries

Germany France

Great Britain

Italy

Bulgaria the Netherlands

Spain

Belgium

Greece

Austria

Source: Pew Research Center

into the host society. The level of integration of newcomers depends on two main factors: how quickly their number grows and how quickly they adapt to the new conditions. Most first-generation migrants are limited to their ethnic group. They settle nearby, practically creating ethnic ghettos, communicate in their national languages, find work “among their own”, but such economic integration does not lead to social integration.

We believe that socio-economic integration is best achieved through ordinary, non-ethnic employment. Access to free labor market, getting a job on an equal basis with local candidates provides legal income, social status, as well as the opportunity to learn the official language, learn the rules and customs of the host society, make friends and build good relations with colleagues among indigenous population. For representatives of the second generation of migrants it is also a chance to develop a successful career in open competition with the representatives of the ethnic majority. The purpose of the research is to study the problem of employment and overcome the pay gap of Muslim immigrants of the first and the second generation in the UK and France as two most indicative countries facing a global challenge of modern immigration.

Research methods

A comparative analysis was chosen as the main method of studying the issues of employment of the representatives of Muslim minorities. It reveals and takes into account many factors explaining the similarities and differences in integration models. In order to determine quantitative indicators we used open data from statistical sources such as the Eurostat statistical office of the European Union, the national statistics offices of the United Kingdom and France. When studying government approaches to Muslim integration we analyzed government acts and official reports. In particular, the Report on the pay gap on ethnic grounds released by the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission in August 2017. We used secondary analysis of sociological surveys and sociological experiments conducted by both independent and government institutions to determine the level of discrimination and social tension against Muslim minorities.

The number and settlement of Muslims in the UK and France

All estimates of the number of Muslims in the UK in recent years are based on the results of the last national census in 2011: 2.71 million Muslims, representing 4.8% of the population in England and Wales [3]. Although the number of Muslims exceeds the total number of votaries of all other non-Christian denominations, it is too early to talk about the Islamization of the country, when only every 20th resident is Muslim. According to the same census, 47% of the total number of Muslims were born in the UK. In 2001, when the issue of religious affiliation first appeared in the census, 1.55 million people were called Muslims, thus the increase of Muslims in the decade between the two censuses was 75%. The main factors in increase are higher birth rate in Islamic families, as well as the growth of migration from Muslim countries [4, p. 23]. According to Pew Research Center, newly arrived migrants provided a 60% increase in the Islamic population in Europe from 2010 to 2016 [1, p. 12]. Therefore, contemplating on the situation of Muslim communities we can assume with confidence that the majority of Muslims in Britain and France are immigrants of two generations.

British Muslims are divided into many ethnic groups. According to data from 2011, 68% (1.83 million) came from Asia, 32% – are of non-Asian origin. Most English-speaking

Muslims are British-born descendants of immigrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India. An interesting fact is that in a survey of 73% of people practicing Islam defined their nationality as British with confidence [4, p.17]

Statistics on British Muslims are diverse and in open access, unlike French statistics. Unfortunately, neither census data nor any other government statistics on French Muslims exist. Under French law, collection of personal information based on race, nationality and religion is prohibited. For a long time, the only practice with regard to immigrants in France was the assimilation policy. In France, assimilation means that anyone wishing to reside permanently in France and obtain French citizenship had to adopt the model of behavior of the local community and preferably marry a French woman/man. The fact that once a migrant is naturalized in France, in official sense, they are no longer immigrants or members of a national or religious minority does not contribute to a correct understanding of the number of Muslims in France as well1. Thus, immigrants who arrived in the 1960s-1980s are beyond the research scope. How many of them remained committed to Islam is unknown.

Independent research centers, commercial analysts, as well as Muslim public organizations that collect information through their channels and conduct various social surveys may help the researchers. Cross-comparisons of European and national statistics are also possible. Officially, the prevailing view is that the number of French Muslims is approximately equal to the number of Muslim immigrants (those born abroad in Islamic countries). The CIA World Factbook yearbook for 2017 estimates the number of Muslims in France as 7–9% of the population (as of July 2017, 67.1 million people) [5]. According to the report of the Supreme Council for Integration, 4 million Muslims lived in France in 2000 [6, p. 33]. Wikipedia, citing Director of the National Institute for Demographic Research (Institut National D’Etudes Demographiques — INED) Francois Eran, states that the number of Muslims in 2017 amounted to 8.4 million2. This figure is well correlated with the estimate of 8.5 million people provided in the latest serious research by Jean-Paul Gourevitch “Les veritables enjeux des migrations” (The True Problems of Migration) [7, p. 176]. However, Azouz Begag, a former Minister for equal opportunities (2005–2007), using differences in the level of religious practice such as “Muslim religion” and “Muslim culture”, introduced into circulation by the Supreme Council for Integration, believes that the number of people belonging to the “Muslim culture” in France in 2017 reaches 15 million.

According to the survey in 2008-2009, in France the share of adult immigrants who consider to be both French and of their ethnic group is 45%, of immigrants’ children born outside France – 58%, of immigrants’ children (both parents are immigrants) born in France – 66% [8]. Most often French Muslims settle inside and around the three largest cities – Paris, Marseille, and Lyon. There, there are five large cathedral mosques. In Lille, Toulouse, Marseille, Muslims make up at least 20% of the population, and in Seine-Saint-Denis department, part of the Paris agglomeration, according to its prefect, there are 700,000 Muslims, and Mohammed is the most common name among the inhabitants. In a survey conducted by the National Institute of Statistics

Table 1. Number of young Muslims in urban areas of Birmingham, 2011

|

District |

Pre-school age, 0–4 |

School age, 5–15 |

||||

|

Total |

Muslims |

% of Muslims |

Total |

Muslims |

% of Muslims |

|

|

Washwood Heath |

3 520 |

2 935 |

83.4 |

7 650 |

6 547 |

85.6 |

|

Bordesly Green |

3 660 |

2 979 |

81.4 |

7 798 |

6 531 |

83.8 |

|

Sparkbrook |

3 282 |

2 670 |

81.4 |

6 715 |

5 526 |

82.3 |

|

Springfield |

3 012 |

2 261 |

75.1 |

6 020 |

4 510 |

74.9 |

|

Aston |

3 190 |

2 109 |

66.1 |

6 046 |

4 173 |

69.0 |

|

Lozells and E. Handsworth |

2 874 |

1 750 |

60.9 |

6 012 |

3 749 |

62.4 |

|

Nechells |

3 322 |

2 086 |

62.8 |

5 677 |

3 710 |

65.4 |

|

Hodge Hill |

2 657 |

1 562 |

58.8 |

5 363 |

3 136 |

58.5 |

|

South Yardley |

2 898 |

1 427 |

49.2 |

5 320 |

2 638 |

49.6 |

|

Source: Census 2011. ONS Table DC2107EW |

||||||

and Economic Studies (Institut national de la statistique et des etudes economiques — INSEE) in 2015, 9,000 secondary school students were interviewed, 25.5% of whom called themselves Muslims [9]. The survey of school students is actually quite revealing. According to sociologists, half of the Muslim population in France today is represented by children and adolescents under 243.

Just like in France, the majority of Muslims in the UK are concentrated in metropolitan areas. 76% of the Muslim population in England reside in Greater London, Birmingham, and Manchester. Muslims in London make up 12.4% of the population, and in the UK there are 35 administrative districts where Muslims make up 10% or more of the population. Among people who called themselves Muslims children and adolescents under 15 years account for 33%. This is a great demographic resource. In general, the entire Muslim population is young and growing rapidly: about 60% are people under 30. The ethnic settlement in some cities has resulted in the emergence of areas where the concentration of Muslim children is more than 50% [3]. This is illustrated in Table 1 .

In general, immigrants rarely dispersed since integration into groups, creation of ethnic enclaves meets their needs to survive and adapt in the new socio-economic, political and cultural environment of the host society [10, p. 150]. But the degree of concentration of ethnic communities in one place of residence is different for England and France. The model of ethnicity-based resettlement dominates in the UK, being typical for three main ethnic communities – Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis. The area of settlement of the group expands mainly due to an increase in the population. Thus, about 40% of Bangladeshis in London live in one of its 33 districts – Tower Hamlets – and account for at least a third of the Muslim population [11, p. 15]. The determining factor in resettlement is ethnic rather than social status. Another model, which, according to the study by A.V. Kapralov [11], is more typical for the French society, is a model of social resettlement. It implies the resettlement of immigrants according to their income and employment. Here, further social integration of immigrants and their even settlement is possible, as well as the concentration of rich immigrants in upscale areas and poor immigrants – in downscale areas [11, p. 15]. In our case, the second option is more common, which is especially evident in Paris and its suburbs. Initially, the majority of immigrants have a lower social status than the local population; they are concentrated in areas with minimum cost of rental housing. But ethnic groups in Paris do not live in isolation in ethnic neighborhoods, but in multinational areas with mixed Arab, black African and white French population.

The emergence of socially disadvantaged areas is very dangerous as they accumulate the most problematic part of the population. Such “ghettos” are characterized by high unemployment level, low incomes, criminality, spread of drug addiction. However, in London there is another problem – “ethnic enclaves” (sometimes even rich ethnic areas), where immigrants exist in their world, reproducing the conditions of their country of origin, where they can exist more or less isolated from the native British and support their traditional lifestyle [11, p. 20].

Analysis of employment practice and income levels of Muslim immigrants in the UK and France in 2000–2017

It is difficult to argue the fact that socioeconomic problems (poor housing, high unemployment rate, difficulties in obtaining education, etc.), as well as religion-related discrimination lead to severe consequences and the strengthening of Islamic extremism. According to many researchers, all significant Muslim demonstrations accompanied by violence, for example in 2005 and 2011, were primarily the result of socio-economic factors rather than religious ones. Therefore, the issue of economic integration of Muslim migrants and the effectiveness of state measures to limit racial or religious discrimination in employment is extremely important in our study.

Data on the economic activity of the UK population in 2011 show that 19.8% of Islamic population had a full-time employment (the entire population – 34.9%), 7.2% of Muslims were unemployed (compared to 4.0 % of the total unemployment in the country) [4, p. 19]. The Muslim community of the country considers such indicators to be the result of racial discrimination and Islamophobia. In 2003, recognizing these negative phenomena, the government adopted The Employment Equality Religion or Belief Regulations, the main articles of which were later confirmed by the Equality Act 2010 [12]. It is noteworthy that the employment situation among Muslims is improving. According to the Office for National Statistics for 2004, 13% of Muslims were unemployed, which is three times higher than that among Christians. Muslims aged 16–24 had the highest unemployment rate – 28% (among Christians of the same age the unemployment rate was significantly lower – 11%). According to the latest census, the share of Muslims without a profession has significantly decreased in 10 years – from 39 to 26%. [4, p. 60]. In 2011, the number of university graduates among Muslim was only slightly lower than the national average: 24 against 27%. In general, there has been a significant increase in the level of education of the non-indigenous population.

In 2011, the share of employed Muslim women was 29% compared to 50% in the country as a whole. The share of Muslim women aged 16–74 who responded that they are fully devoted to home and family amounted to 18%, which is three times higher than the national average [4, p. 62]. This is largely due to the fact that in Islamic world, the majority of women after marriage give priority to their family, but it is also of great importance that they still feel some discrimination in employment [4, p. 63]. However, the share of Muslim women among university students is quite high – 43%, in some municipal units the share of Islamic women studying fulltime exceeds the share of Muslim men. Quite impressive are the data on the share of Muslims employed in top management and high-paid jobs – 5.5% against 7.6% across the population. 9.7% of Muslims are self-employed or work in small business, which almost equals the share of all self-employed in the country (9.3%) [4, p. 64].

In order to study the financial situation of Muslim immigrants it is recommended to refer to the report of JRF (Joseph Rowntree Foundation) “Reducing Poverty in the UK” published in 2014. One of the articles is called “Religion and Poverty”. This is a rare case when the relations between religion and material well-being is investigated. Most studies are based on the ethnic origin of the subjects. The research framework is rather impressive: there were 60,925 respondents who answered questions about their religious identity [13]. According to the JRF research, the group of poorest UK inhabitants contains the largest number of Muslims. The report characterizes the poverty level as less than 60% of the family’s annual median income, which at the end of 2017 amounted to 27,300 pounds [14].

According to the above calculations, 50% of Muslims live in poverty. However, the most prosperous group is the Jews, where the share of the poor does not exceed 13%. To compare, we present other groups: the share of the poor among the Sikhs is 27%; among the Hindus – 22%; Catholics – 19%; Anglicans – 14%, among people who do not belong to any religion – 18% [13, p. 34]. According to the authors, the causes of poverty lie in the history of Muslim immigration to the UK, and are primarily explained by the fact that they are immigrants of the first generation. Among the most important causes of poverty are also lack of English skills, the number of young children in the family, which hinders the employment of mothers and reduces per capita income. The majority of the poorest members of the Muslim communities come from Pakistan and Bangladesh. Most immigrants from these countries did not have professional qualifications and their English was satisfactory. However, in the second generation, these immigrants achieve much better economic results. Women employment is more difficult as it is customary for women to take care of children and the household in their traditional environment. The Muslim Council of Britain recognizes that an unmarried Islamic woman is 1.5 times more likely to find a job than a married woman [4, p. 63].

Thus, the authors of the reports do not consider ethnic or religious discrimination to be the main reason for low income of immigrants from Pakistan and Bangladesh, mentioning, however, that the religious factor becomes important if the potential candidate prefers to wear national clothes that sharply distinguish them from the general background or otherwise emphasize their religious beliefs. The authors also note that the risk of becoming poor is much greater among Muslims than that of other groups, but the reason for that is not clear enough.

Unfortunately, we do not have comparable statistics on the Muslim population in France. However, there is no doubt that immigrants are very vulnerable in the labor market as the unemployment rate in France is much higher than in the UK. In 2015–2016 it varied from 9.7 to 10.2% [15]. In 2017, the number of officially reported unemployed amounted to 3.55 million people. The share of Muslims among them is unknown. Most studies indirectly confirm that the share of employed Muslims is significantly lower than the national average. Thus, in 2014 in areas of their residence, in depressed areas, the unemployment rate of people aged 15–64 years comprised 26.7% compared to 10% of the national average [16]. Although the migration crisis in Europe did not affect France as much as Italy or Germany, according to Eurostat, the number of forced migrants from Muslim countries also increased: from 64,000 in 2014 to 84,000 in 2016 [17]. Since the influx of humanitarian migrants does not correspond to the needs of the labor market, this makes it difficult to solve the problem of employment of the new comers.

The low level of migrants’ education significantly limits the opportunities of their inclusion in production – to mainly unstable, low-paid places jobs with poor working conditions and an increased risk of ending up on the street. According to Eurostat, in France in 2016 42% of the population aged 15–74 did not have a complete secondary education, while in the EU as a whole – only 35%; the unemployment rate of those of the same age born in other countries was 17%. In 2015, 24% of migrants over 18 were considered poor because their income was below 60% of the median income in the country, 10% suffered from severe material deprivation (Eurostat, 2017). Migrants’ limited access to the labor market significantly complicates their socioeconomic integration and mobility [18, p. 20].

One may get a certain idea of the economic integration of the Muslim population from a joint study of national institutions of INSEE and INED conducted in 2008-2010 under the poetic name “Trajectories and Origins”4, the purpose of which was to establish a link between the living conditions and opportunities for the advancement of individuals in the society with the social and ethnic (immigrant) background

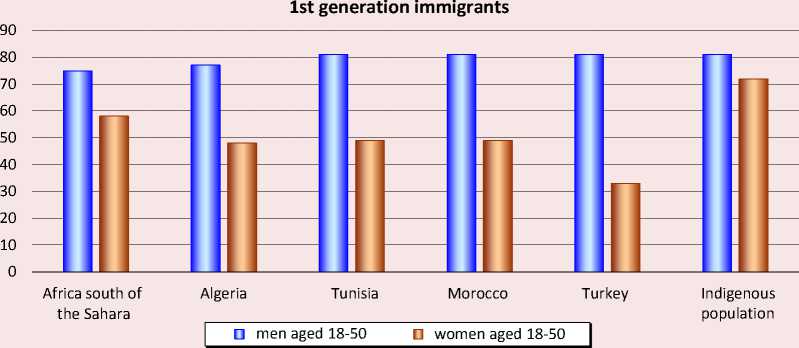

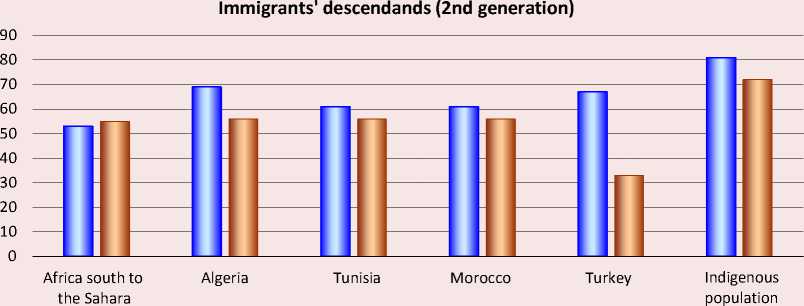

[19]. The study covers 21,000 people of different age and background, both immigrants and their children and the local French population. The main idea of this fundamental research was to determine the extent to which immigrants can use the resources and opportunities of the French state and society for successful integration and personal growth. For this purpose the dynamics of differentiation and homogenization within one group and between groups was determined. The survey participants told about their parents and country of origin, income level, education, profession, and marital status. The survey confirmed that the lowest employment rate was among immigrants from Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Turkey, subSaharan Africa. These data are graphically presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3 .

The comparison of generations demonstrates that women employment is growing, but in general, immigrants’ children in France are left without employment more often than their parents. The reason for this is not clear, but it definitely is not the youth of the second generation. Three quarters of first-generation immigrants surveyed entered the country when they were under 30 and were nevertheless in demand in the labor market. Moreover, when comparing groups of people aged 18–30 and 31–50, it was revealed that the risk of losing a job increases after 30; for example, for immigrants from Algeria, it was 2 times higher than that of the indigenous population, and for immigrants from Turkey – 1.6 times.

Despite the fact that the question of religion was asked to all respondents of INED/INSEE, the study focuses on the specific features of integration of different ethnic groups. How legitimate is this projection on the Muslims? Here we are guided by the idea of Islam as a very strong traditional religion, the importance

Figure 2. Employment of French immigrants by country of origin (% of population), 2009

Source: compiled from INED and INSE data (Trajectories and Origins. Survey on Population Diversity, 2010 in France).

Figure 3. Employment of the second generation of French immigrants by country of origin (% of population), 2009

men aged 18-50 women aged 18-50

Source: compiled from INED and INSEE data (Trajectories and Origins. Survey on Population Diversity, 2010 in France). Available at: of which, like the number of followers, is steadily growing. It can be assumed that at least 80% of immigrants from Maghreb countries and their descendants consider themselves Muslims. According to the study conducted by the French Institute of Public Opinion (Institut frangais d’opinion publique — IFOP) for La Croix newspaper in 2011, 75% of immigrants from Muslim countries considered themselves religious.

The qualification level and language skills are important basic criteria for employment. About 40% of immigrants who came to France in 1990–2000 had no qualifications (or had only primary or lower secondary education), while 34% had higher education. These figures are much better than those of the first-generation immigrants (1960–1970s), 76% of whom had no secondary education or professional qualifications and only 11% graduated from universities. Many immigrants coming to France from the former French colonies had good French skills. 77% of people from West and Central Africa, 53% from the Sahel zone, 44% from North African countries demonstrated good language skills [19, p. 33]. Compared to immigrants from Portugal or Turkey, Africans had an important advantage. However, studies and opinion polls show that it is Muslim immigrants who have been most often discriminated against in employment.

We cannot clearly state that religion is the main cause of discrimination. During the INED/INSEE survey, the majority of respondents pointed to discrimination by race and country of origin, a smaller share linked discrimination to issues of religion, gender or age. (Indeed, it is difficult to distinguish between the “Muslim” and “non-Muslim” aspect of the issue since in Europe almost all Muslims come from the same country or region. For example, Muslims in Germany are primarily Turks, Muslims of France mostly come from Maghreb countries). However, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published in December 2010 explicitly point to the existence of religious discrimination. American researchers from the United States conducted a “mail questionnaire” sending identical resumes with Arabic names and Muslim backgrounds and Christian stating the participation in Catholic organizations to the leading national recruiting agency to determine the difference between the employment opportunities and income levels of the second-generation Muslim immigrants and

French Christians. A Muslim was 2.5 times less likely to find a job than a Christian. A similar study with similar results was conducted by the U.S. Department of Labor in 2013. In 2009, the Open Society Institute noted an increase in religious discrimination: 55.8% of Muslim and 43% of non-Muslim respondents stated that in 2009 they were more likely to face racial prejudice than 5 years ago. 68.7% of Muslim and 55.9% of non-Muslim respondents believed that the same could be said about religious prejudices. More than 90% of all respondents believed that Muslims suffer from religious prejudices of the society [20].

According to the research conducted by Institut Montaigne in 2013–2014, 44% of second-generation immigrants faced discrimination at least once in their lives. Having the same professional qualifications, Catholics are 30% more likely to be called for an interview than the Jews, and twice more likely than Muslims, especially Muslim men, who had to apply four times more resumes than Catholics to be invited for an interview [21]. Entrepreneurs ignore people of a different race when selecting candidates to work with clients or for leadership positions. Despite the fact that the 2006 law “On equal opportunities” proclaims personnel recruitment based on anonymous resumes the latter are not used. According to the INED/INSEE survey, the economic activity of Muslims is most often limited to work in construction (25% – the first generation, 16% – the second), manufacturing (17 and 16%), as well as the service sector (HoReCa – 53 and 59%) [22, p. 8]. Muslim women are most likely to find a job in healthcare and social sector. Muslims are almost not introduced in public service – there are 10 times less Muslims than the representatives of the indigenous population.

In early 2015, Prime Minister of France Manuel Valls declared there is “territorial, social and ethnic apartheid” in the country, recognizing the existence of discrimination on racial and ethnic grounds. We have already mentioned the model of “social resettlement” typical of French immigrants: in disadvantaged suburbs, which after January 1st, 2015 became known as “priority zones” despite all state efforts, the share of unemployed, especially among young people is still the highest. 5.5 million people live in 1,500 priority areas; more than half of these people are immigrants of the first and second generation. Particularly vulnerable are minorities who have been able to rise above their social environment and receive a good education. As emphasized in the report of the research center of the National Observatory of Urban Policy in 2015, those with higher education over 30 are 22% less likely to work within trade if they live in a priority urban area. Muslims living in migrant areas are much more religious than those scattered in mixed areas, and 90% of young people aged 18–25 eat Muslim food and do Ramadan. Failures in the socio-economic integration of migrants, the feeling of social segregation lead to the fact that young people in suburbs oppose Islam to republican values.

In the UK, on the contrary, the influence of the territorial factor on the unemployment rate is not recorded, but among other factors there is racial discrimination and Islamophobia. In the framework of the survey undertaken on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) approximately 3,000 applications for 987 positions were sent under false names of Nazia Mahmud, Mariam Namagembe and Alison Taylor. All three candidates had British education, very similar qualifications and experience. Alison Taylor received a positive response from employers in every ninth case, while candidates with “non-British” names received responses only at every sixteenth position5.

The most recent and interesting statistical study on the economic inequality of migrants in the UK is a study by the University of Essex conducted in 2015–2017 on behalf of the Commission on Human Rights to study the pay gap between white Britons and the representatives of non-white minorities, identify areas of violation and appeal to state intervention, if necessary [23]. Data were taken from quarterly reports of the National Bureau of Statistics (Labor Force Survey) [24]. This is the only source that records the ethnic origin of employees. To what extent are the data on ethnic minorities applicable to Muslims, since the question of religious affiliation was not raised in the study? According to the 2011 Census, 31.6% of the black and nonblack population in the UK are Muslim, i.e. each third [25]. Some ethnic groups such as Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Somalis, are almost entirely Muslim. Therefore, we consider it acceptable to extrapolate the data of the study on the pay gap among national minorities to the UK Muslim population within certain limits.

It is clear that the pay gap is a long-lasting phenomenon. Ethnic minorities have always earned less than the indigenous population. This is often determined by the social background, yet sometimes it is only the matter of discrimination. We have repeatedly mentioned that newcomers do not know the language, are not qualified enough, are unfamiliar with the UK culture. But studies prove that immigrants often work in lower-paid industries with higher qualifications. In

2002–2014 white British people, both men and women, earned more than the rest in 70% of cases, but the gap varies greatly among different ethnic groups, and the wages of women and men are very different. Income is highly dependent on the place of birth – the UK or another country. However, there are exceptions: for example, Indian and Chinese men earn the same as white UK citizens regardless of their place of birth. But the situation among Pakistanis and Bangladeshis born abroad is worse [23, p. 8]. For example, a man who comes from Bangladesh receives an average of 48% less. His sons born in Britain reduce the gap to about 26%. The same image is for Pakistanis – 31 and 19%.

The situation for women is debatable. Women from Bangladesh and Pakistan earn 12% less than the average earnings of the white majority, other ethnic groups do not make a significant difference, or immigrants have higher wages. Thus, black African women receive 21% more than their white competitors [23, p. 55].

What are the possible flaws in such a report? It only gives an idea of wage employment. It does not take into account the self-employed and extra income (side activity), while 10% of Muslims in the UK are self-employed. We cannot limit ourselves to figures and assume that the difference in pay is due to ethnic discrimination. It is necessary to take into account the full range of business qualities valued by employers. Only if the difference in pay is not explicable can we talk about discrimination. What do the authors of the report see as the main reason for the pay gap? As tempting as the simple idea that ethnic minorities are paid less because of racial discrimination may seem, the image is somewhat different. It turns out that minorities tend to gravitate to certain professions, or more precisely, to spheres of employment, and in many respects this fixation is due to the pay level at their work.

Contemplating about the pay situation of Muslim minorities in France, we can note the already mentioned 2008–2009 INED/INSEE project. According to the survey, 97% of employed migrant men worked full-time, only about 70% – women. 88% of economically active men and 92% of women were hired for wage. Against this background, immigrants from Turkey stood out sharply – 74% of first-generation immigrants and 83% of their sons were hired, the rest were selfemployed [19, p. 69].

To quantify the pay gap, French researchers studied the hourly pay of men and women in full-time and part-time, simultaneously determining whether part-time employment is desirable or forced. They came to an interesting conclusion that according to a combination of factors (country of origin, language skills, qualifications, occupation, etc.), the majority of immigrants receive a pay comparable to the pay of the ethnic French. But to come to this conclusion it was necessary to conduct factor analysis of statistics.

The relative pay of immigrants from all countries except Spain, Italy and Portugal was lower than that of the indigenous population. Men from Turkey and African countries earned less of all. As for women, the pay gap between the indigenous population was observed only among Turkish women. Trying to explain the pay gap the researchers constructed four models starting with basic statistics and each time complicating factor analysis. Thus, in pure statistical terms, immigrants from Algeria had 13% less income than the indigenous French. After adding indicators such as education, professional qualifications the figure was 16% less. With the introduction of other features such as time spent in France, language skills, citizenship, the gap was reduced to minus 7%, and after adding very specific requirements to skills and work experience, the pay gap was reduced to 1–2% [19, pp. 71–72]. Thus, according to the econometric model it turned out that discrimination is insignificant.

In our view, it is still impossible to reduce the unique economic characteristics of migrants to mathematical models. There is a number of factors and conditions that are not limited to statistics with regard to the Muslim minorities. The main thing here is to understand why social mobility does not work well for Muslims in France. After all, their earnings do not differ much because Muslims or national minorities in general are paid less, but because they are mostly employed in low-paid economic sectors. The same report notes that migrants’ children, for example from Algeria or Tunisia, often inherit their parents’ activity, although they demonstrate certain improvement in skills, shifting from purely manual labor to partially automated manual labor. This raises the questions about the effectiveness of the French policy towards Muslim migrants.

Conclusion

The economic integration of Muslims is a fundamental element in the complex relationship between immigrants and the host society. The author attempts to generalize and analyze diverse statistics for 2001–2017 obtained as a result of surveys of the Muslim population, especially first- and second-generation immigrants from Asia and Africa legally residing in the UK and France. The analysis leads to some cautious conclusions about the level of socialization of these religious minorities achieved to date.

In the UK and France, different models of socio-economic interaction with immigrant minorities have historically been implemented, but in both countries their inclusion in economic activity is slow and incomplete. The main problems today are a sharp increase in the number of people in Muslim communities, a relatively low level of education and skills of newcomers, their unwillingness to integrate and acculturate. This is reflected in concentrated resettlement and creation of ethnic neighborhoods, the reproduction of traditional ethnic spheres of employment, which is a serious problem for both economic integration and inclusion of Muslims in the civil societies of the host countries.

The second generation of British Muslims demonstrate serious improvements in their status and income, especially those born in the UK. 73% of Muslims certainly choose “British” as their cultural identity. In France the opposite is observed. Immigrant children do not improve their socio-economic status relative to their parents’ status; positive changes are insignificant. With a certain degree of confidence we can say that the UK policy towards Muslim minorities is more balanced and provides better results.

Список литературы Economic integration of immigrants through overcoming inequalities in employment and wages. Comparative analysis of British and French Muslim communities

- Europe’s Growing Muslim Population. Demographic Study. November 2017. Pew Research Center. Available at: http://www.pewforum.org/2017/11/29/europes-growing-muslim-population/

- Muslims in European Union. Discrimination and Islamophobia. EUMC, 2006.

- 2011 Census Data. Office for National Statistic. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census/2011censusdata

- British Muslims in Numbers. A Demographic, Socio-economic and Health profile of Muslims in Britain drawing on the 2011 Census. The Muslim Council of Britain, January 2015. Available at: http://www.mcb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/MCBCensusReport_2015.pdf

- The World Factbook, CIA, 2017. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/fr.html

- Ponkin I. Islam vo Frantsii [Islam in France]. Moscow, 2005. 196 p.

- J.-P. Gourévitch. Les veritables enjeux des migrations. Monaco, 2017, 220 p.

- Simon P. French National Identity and Integration: Who Belongs to the National Community. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. 2012.

- Être né en France d’un parent immigré. INSEE, Enquête emploi de 2015, enquête annuelle de recensement de 2015. Available at: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3303358?sommaire=3353488

- Kastorjano R. Integration und Suche nach kollektive Identitaet von Einwanderervereinigungen in Frankreich. Migration und Staat R. Leveau, W. Ruf. Muenster, 1991. Cit. Ex. Kuropyatnik A.I. Immigration and national society: France. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsial’noi antropologii=Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology.

- Kapralov A.V. Rasselenie immigrantov v krupneishikh gorodskikh aglomeratsiyakh zarubezhnoi Evropy: avtoref. dis. na soisk. uch. step. kand. geograf. nauk [Migrant Resettlement in Major Urban Agglomerations in Europe abroad. Candidate of Sciences (Geography) dissertation abstract]. Moscow, 2009.

- Equality Act 2010. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/pdfs/ukpga_20100015_en.pdf

- Reducing Poverty in the UK: A Collection of Evidence Reviews. 2014. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Available at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/Reducing-poverty-reviews-FULL_0.pdf

- Household disposable income and inequality in the UK: financial year ending 2017 Available at: https://www.ons. gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/ householddisposableincomeandinequality/latest#median-household-disposable-income-1600-higher-than-pre-downturn-leve

- Conjoincture en France. March 2017. INSEE. Available at: https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/2662654?sommaire=2662688&q=unemployment

- L’Observatoire national de la politique de la ville (ONPV).2016. Rapport annuel 2015. Available at: http://www.onpv.fr/uploads/media_items/rapport-onpv-2015.original.pdf

- Population by educational attainment level, sex, age and country of birth; Employment rates by sex, age and country of birth; Unemployment rates by sex, age and country of birth. At-risk-of-poverty rate by broad group of country of birth; severe material deprivation rate by broad group of country of birth. Eurostat. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

- Preobrazhenskaya A.A. The French model of integration of immigrants: test of time. Chelovek. Soobshchestvo. Upravlenie=Human. Community. Management, 2017, vol. 18 (3), pp. 18-36. (In Russian).

- INED-INSEE, Trajectories and Origins (TeO), Survey on Population Diversity in France. Initial Findings, 2010. Available at: https://teo-english.site.ined.fr/

- Adida C.L., Laitin D.D., Valfort M.-A. Identifying barriers to Muslim integration in France. PNAS December 28, 2010. 107 (52) 22384-22390. Available at:

- DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1015550107

- Discriminations religieuses a l’embauche: une realite. Institute Montaigne, 2015. Available at: http://www.institutmontaigne.org/res/files/publications/20150824_Etude%20discrimination.pdf

- Emplois, salaires et mobilité intergénérationnelle. Série Trajectoires et Origines (TeO) Enquête sur la diversité des populations en France. Available at: http://www.ined.fr/fichier/t_publication/1611/publi_pdf1_publi_pdf1_doc. travail.182.pdfNumber:182

- The Ethnicity Pay Gap. Equality and Human Rights Commission. Research Report 108. 2017. Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/research-report-108-the-ethnicity-pay-gap.pdf

- Labour Force Survey. Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentand labourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/labourmarketstatusbyethnicgroupa09

- 2011 Census Analysis: Social and Economic Characteristics by Length of Residence of Migrant Populations in England and Wales. November 2014. Office for National Statistics. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160107131432/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_381447.pdf