Effect of pranayama on anxiety, depression and stress levels in post-graduate students: correlation with serum cortisol and hemoglobin levels

Автор: Nagar L., Betal Ch., Chauhan I., Tyagi P.

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.20, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Background: Anxiety, depression and stress (ADS) are prevalent mental health disorders among university students due to the demanding nature of their academic pursuits. Pranayama yogic breathing (PYB), a controlled breathing technique has been suggested as a potential intervention to alleviate these psychological maladies.

Pranayama, anxiety, depression, stress, serum cortisol, hemoglobin

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143182790

IDR: 143182790

Текст научной статьи Effect of pranayama on anxiety, depression and stress levels in post-graduate students: correlation with serum cortisol and hemoglobin levels

University students face numerous challenges and pressures in their academic pursuits due to the demanding nature of academic, social and financial goals, which often contribute to higher levels of Anxiety, Depression and Stress (ADS) (Andrews & Wilding, 2004; Mofatteh, 2020). ADS and other mental illnesses of these students are critical factors that can influence their academic performance and overall quality of life (Andrews & Wilding, 2004; Zada et al. , 2021). Anxiety disorders entail ongoing uneasiness and worry, often lacking a clear trigger. In contrast, depression, a mood disorder, leads to emotional responses tied to health problems, affecting daily life with symptoms like sadness, guilt and loss of interest. Stress, which arises from non-compliance with environmental conditions, triggers psychological and biological changes, elevating the risk of illness (Mirzaei et al. , 2019).

ADS can significantly impact students' academic performance, leading to concentration problems, memory issues, decreased motivation and poor decision-making. Social withdrawal and substance abuse can worsen these conditions (Mofatteh, 2020; SAMHSA, 2021). Additionally, chronic ADS harm physical health, including headaches, digestive problems, weakened immunity and increased cardiovascular risk (SAMHSA, 2021). University students facing ADS have a higher risk of suicidal thoughts and self-harm (Asif et al. , 2020; Martínez-Líbano et al. , 2023). A survey was conducted among 500 university students which showed that a significant proportion experienced ADS, with percentages of 88.4%, 75%, and 84.4%, respectively (Asif et al. , 2020). In another study involving 1,062 higher education students, a notable prevalence of ADS was observed, with rates of 69.2%, 63.1% and 57%, respectively (Martínez-Líbano et al. , 2023).

Studies showed that PYB offers various psychophysiological benefits which is closely tied to nervous system. This practice also contributes to mood enhancement, promoting better sleep and increasing parasympathetic tone (Jayawardena et al. , 2020). Therefore, PYB may reduce stress via serum cortisol (SC) regulation, enhancing relaxation through autonomic system balance and potentially improving hemoglobin (Hb) indirectly by boosting oxygen uptake. These interconnected benefits highlight the holistic benefits of PYB (Sengupta, 2012).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

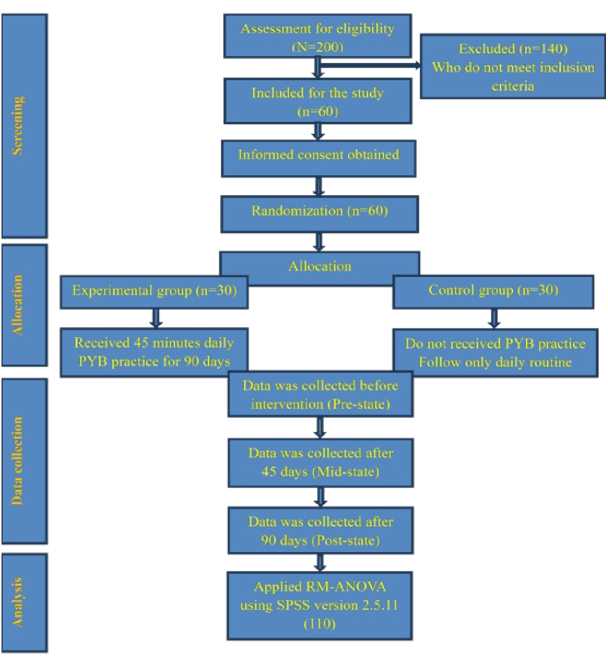

The study is mainly focused on the Post Graduate Students (PGSs) who have the high ADS score. The participants were recruited from various departments of H.N.B. Garhwal A Central University. A total of 200 subjects were included in this study using the ADSS (Anxiety, Depression and Stress Scale) assessment and 60 participants who met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to the experimental group (n=30) and the control group (n=30). The experimental group engaged in PYB practice for three months, with daily practice duration of 45 minutes, excluding Sundays and gazette holidays. The sessions were conducted under the supervision of the researchers. The control group participants did not have any specific tasks and they continued their normal daily routine activities. Data were collected at three time points: Pre (before the intervention), Mid (after 45 days) and Post (after 90 days). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study, ensuring their voluntary participation and understanding of the study's purpose and procedures. Figure 1 presents summarized screening, allocation, data collection and analysis of the study.

Inclusion/ Exclusion Criteria

Post Graduate Students (PGSs) with high ADS (Anxiety, Depression and Stress) score and age ranging from 21 to 24 (mean age 22.95±1.15) years with general health status but no prior exposure to PYB practice were included in the study. PGSs with major psychological problems, low ADS and unwillingness to participate in PYB practice were excluded from the study. But the PGSs of both groups were forbidden strictly to take any kind of medicine, counseling, psychotherapy and physical exercise or physiotherapy, so that the result of the treatment variable may not be contaminated and thus the experiment was conducted in a completely controlled condition.

Assignment of Treatment

Measurements

The data on ADS of the PGSs were collected by administering the Anxiety Depression Stress Scale (ADSS), developed by Pallavi Bhatnagar of the National Psychological Corporation, Agra (U.P.), Similarly, data on SC level in ug/dl were collected by using Electro Chemi Luminescent Immuno Assay (ECLIA) technique in pathology lab. Blood samples were collected from both the experimental and control groups between 8.00 to 10.00 AM and promptly sent to the laboratory for further estimation. The data on Hb level in gm/dl were collected by using same blood sample.

Data Analysis

Table 4 displayed the Mean ± SD values for ADS, SC and Hb levels of both the experimental and control groups. A repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) was adopted using SPSS version 2.5.11 (110), considering two factors: groups with two levels (experimental and control) and states (pre, mid and post). Post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction were performed to account for multiple comparisons and the Huynh-Feldt epsilon was applied to adjust the degrees

of freedom.

RESULTS

Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics of the selected participants, comprising 27 males and 33 females, with age ranging from 21 to 24 years (mean age: 22.95±1.15). At the beginning of the study, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups for all variables. All the 60 subjects successfully completed the study and no adverse events were reported during the intervention period.

The outcomes of the repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) are as follows:

The results of the repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) revealed significant differences between the groups for anxiety (p<0.001), depression (p<0.001), stress (p<0.001), serum cortisol (SC) (p<0.001) and hemoglobin (Hb) (p<0.001). Additionally, significant differences were observed between the states for anxiety (p<0.001), depression (p<0.001), stress (p<0.001), SC (p<0.001) and Hb (p<0.001). Notably, there were significant interactions between the groups and states for anxiety (p<0.001) depression (p<0.001), stress (p<0.001), SC (p<0.001) and Hb (p<0.001), indicating interdependence among these variables. Specific values for F, df, Huynh-Feldt epsilon and p-values can be found in Table 3.

Post hoc analysis within-groups yielded the following findings:

-

(i) In the experimental group, there were significantly lower anxiety scores from the pre to mid-state (p<0.001, 95% CI [0.83, 1.90]) and from the pre- to post-state (p<0.001, 95% CI [2.16, 3.63]). However, no significant difference was observed in the control group.

-

(ii) The experimental group displayed significantly lower depressions scores from the pre to mid-state (p=0.001, 95% CI [0.38, 1.61]) and from the pre- to poststate (p<0.001, 95% CI [2.49, 3.70]). Conversely, no significant difference was found in the control group.

-

(iii) The stress scores were significantly lower in the experimental group from the pre to mid-state (p=0.001, 95% CI [0.43, 1.90]) and from the pre- to post-state (p<0.001, 95% CI [2.41, 4.05]), while no significant difference was observed in the control group.

-

(iv) The experimental group displayed significantly lower SC levels from the pre to mid-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [1.51, 2.49]) and from the pre- to post-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [4.17, 5.35]). Conversely, no significant difference was found in the control group.

-

(v) Similarly, the Hb levels were significantly higher in the experimental group from the pre to mid-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [-1.07, -0.57]) and from the pre- to post-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [-2.72, -2.24]), while no significant difference was observed in the control group. Post hoc analysis between groups revealed the following findings:

-

(i) The experimental group displayed significantly lower anxiety scores as compared to the control group at mid-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [-2.23, -0.76]) and poststate (P<0.001, 95% CI [-3.78, -2.47]). However, there was no significant difference between the groups at prestate.

-

(ii) The experimental group exhibited significantly lower depression scores as compared to the control group at the mid-state (P=0.001, 95% CI [-1.83, -0.49]) and post-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [-4.03, -2.56]).

Conversely, there were no significant differences between the groups at pre-state.

-

(iii) The stress scores were significantly lower in the experimental group compared to the control group at the mid-state (P=0.01, 95% CI [-1.97, -0.36]) and post-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [-4.08, -2.72]). However, there were no significant differences between the groups at prestate.

-

(iv) The experimental group exhibited significantly lower SC levels as compared to the control group at the mid-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [-2.72, -1.17]) and poststate (P<0.001, 95% CI [-5.19, -3.75]). Conversely, there were no significant differences between the groups at pre-state.

-

(v) Similarly, the Hb levels were significantly higher in the experimental group compared to the control group at the mid-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [0.47, 1.59]) and post-state (P<0.001, 95% CI [2.18, 3.34]). However,

there were no significant differences between the groups at pre-state.

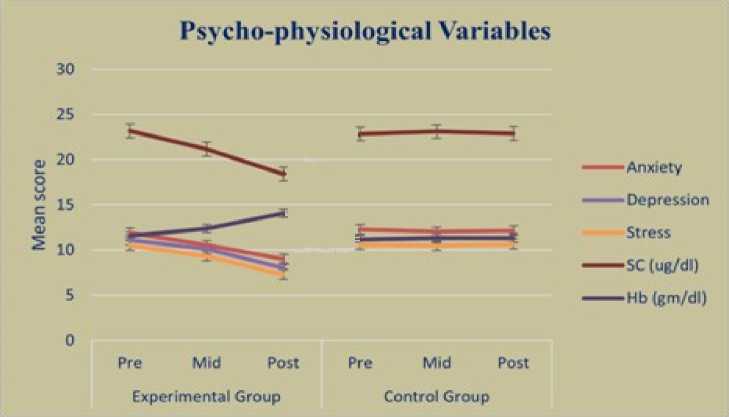

The post hoc comparisons within groups and between groups are presented in Table 4 and graphical presentations can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Flow chart summarized screening, allocation, data collection and analysis.

Table 1 : Assignment of pranayama yogic breathing (PYB) in experimental group.

|

S.no |

Name of PYB practice |

Duration (Minutes) |

Method |

Benefits |

|

1 |

Sahaja PYB |

05 |

Observe natural breath without controlling it, shifting awareness through different areas |

Increases mindfulness, concentration, creativity, energy levels, inner peace, thought control, emotional stability |

|

2 |

Anuloma-viloma PYB |

10 |

Alternate nostril breathing with equal inhalation and exhalation |

Balances breath and brain hemispheres, calms anxiety, heals cardiovascular and nervous disorders |

|

3 |

Bhramari PYB |

10 |

Humming sound while breathing, focus on ajna chakra |

Relieves stress, anger, anxiety, insomnia, enhances healing capacity, strengthens voice, |

|

4 |

Ujjayi PYB |

10 |

Breathing through the throat with a soft snoring-like sound, slow and deep breaths |

Tranquilizing practice, soothes nervous system, calms the mind, cure insomnia, benefits in high blood pressure |

|

5 |

Bhastrika PYB |

10 |

Forceful inhalation and exhalation with diaphragm and abdomen movements |

Burns toxins, aids women during labor, increases oxygen exchange and metabolism, strengthens the nervous system |

Table 2: Baseline characteristics of post-graduate students (PGSs) (n=60).

|

Experimental |

Control |

Total |

|

|

Age Group (mean±SD) |

22.93 (1.04) |

22.96 (1.27) |

22.95 (1.15) |

|

Gender (%) |

Male 16 (53.33) |

11 (36.66) |

27 (45) |

|

Female 14 (46.66) |

19 (63.33) |

33 (55) |

|

|

Anxiety |

Pre (mean±SD) |

Pre (mean±SD) |

|

|

Depression |

11.90(1.21) |

12.27(1.23) |

|

|

Stress |

11.13(1.30) |

11.17(1.20) |

|

|

SC (µg/dl) |

10.50(1.33) |

10.60(1.35) |

|

|

Hb (gm/dl) |

23.17(1.80) |

22.85(1.59) |

|

|

11.57(1.03) |

11.15(1.05) |

Note; SC-Serum Cortisol; Hb -Hemoglobin

Table 3: Summary of Analysis of Variance (RM ANOVA) of Psycho-Physiological Variables.

|

Variables |

Factors |

F(df) |

Huynh-Feldt (ε) |

P |

Partial Eta Squared (ƞp2) |

|

ADSS |

|||||

|

Anxiety |

Group |

40.67(1, 58) |

0.935 |

<0.001 |

0.41 |

|

States |

33.32(1.87, 108.47) |

0.935 |

<0.001 |

0.36 |

|

|

Group X States |

27.99(1,58 X 1.87,108.47) |

0.935 |

<0.001 |

0.32 |

|

|

Depression |

Group |

30.63(1, 58) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.34 |

|

States |

34.26(2.00, 116.00) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.37 |

|

|

Group X States |

41.50(1,58 X 2.00,116.00) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.41 |

|

|

Stress |

Group |

38.34(1, 58) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.39 |

|

States |

24.46(2.00, 116.00) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.29 |

|

|

Group X States |

27.30(1,58 X 2.00,116.00) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.32 |

|

|

SC |

Group |

32.35(1, 58) |

0.983 |

<0.001 |

0.35 |

|

States |

126.37(1.96, 113.99) |

0.983 |

<0.001 |

0.68 |

|

|

Group X States |

126.89(1,58 X 1.96,113.99) |

0.983 |

<0.001 |

0.68 |

|

|

Hb |

Group |

28.07(1, 58) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.32 |

|

States |

161.49(2.00, 116.00) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.73 |

|

|

Group X States |

136.71(1,58 X 2.00,116.00) |

1.000 |

<0.001 |

0.70 |

Note; ADSS- Anxiety, depression, Stress Scale, SC-Serum Cortisol; Hb -Hemoglobin

Table 4: Results of Outcome Measures at Pre, Mid and Post of Experimental and Control Groups. Values are Given in Mean and Standard Deviation.

Variables Experimental Group Control Group

(n=30) (n=30)

|

Pre |

Mid |

Post |

Pre |

Mid |

Post |

|

|

ADSS |

||||||

|

Anxiety |

11.90(1.21) |

10.53(1.54) ***$$$ |

9.00(1.23) ***$$$ |

12.27(1.23) |

12.03(1.29) |

12.13(1.30) |

|

Depression |

11.13(1.30) |

10.13(1.30) ***$$$ |

8.03(1.49) ***$$$ |

11.17(1.20) |

11.30(1.29) |

11.33(1.34) |

|

Stress |

10.50(1.33) |

9.33(1.66) ***$$ |

7.27(1.31) ***$$$ |

10.60(1.35) |

10.50(1.43) |

10.67(1.32) |

|

SC (ug/dl) |

23.17(1.80) |

21.16(1.33) ***$$$ |

18.40(1.28) ***$$$ |

22.85(1.59) |

23.11(1.66) |

22.88(1.49) |

|

Hb (gm/dl) |

11.57(1.03) |

12.39(1.05) ***$$$ |

14.05(1.07) ***$$$ |

11.15(1.05) |

11.36(1.10) |

11.29(1.15) |

Note; ADSS- Anxiety, depression, Stress Scale, SC-Serum Cortisol; Hb -Hemoglobin

Note; (***=P<0.001, **=P<0.01, *=P<0.05) Based on Bonferroni adjusted Post hoc analysis when Mid and Post States were compared with respective Pre-value. ($$$=P<0.001, $$=P<0.01, $=P<0.05) Based on Bonferroni adjusted Post hoc analysis when Pre, Mid and Post States of the Experimental Group were compared with the respective States of the Control Group.

Figure 2. Graphical presentation of psycho-physiological variables.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study indicate that the experimental group, which received the pranayama yogic breathing (PYB), exhibited significant improvements in psycho-physiological variables compared to the control group. Specifically, the experimental group showed lower anxiety, depression and stress (ADS) scores as well as lower serum cortisol

(SC) levels and higher hemoglobin (Hb) levels. These results suggest that the intervention had a positive impact on the psycho-physiological well-being of the Post Graduate Students (PGSs).

The reduction in ADS scores in the experimental group of present study aligns with previous researches. Jagadeesan et al (2022) found that Bhramari PYB reduced ADS scores significantly (p<0.05) in COVID-19 patients in home isolation. Similarly, Shah & Kothari (2019) demonstrated that Nadi-shodhana PYB, along with conventional physiotherapy, improved lung functions and lowered ADS levels significantly (p<0.01) in post CABG patients. Other studies also support the positive effects of PYB on lowering ADS (Brown & Gerbarg, 2005; Chandrababu et al, 2019).

Maheshkumar et al (2022) found that yoga participants had higher salivary cortisol responses initially but showed reduced levels (p=0.03) over time due to practice of PYB. Similarly, other studies back up our findings in positive effect of PYB on cortisol (Abedi Amiri et al , 2018; Balaji & Varne, 2017; Kamei et al , 2000; Ma et al. , 2017). Sahu and Kishore (2015) found significant impacts (p<0.001) of Bhramari PYB and Jyoti Dhyan on Hb levels and alpha EEG in college students, suggesting improved blood circulation and oxygen delivery.

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The research was carried out with a limited sample size within a single university campus located in H.N.B. Garhwal A Central University. ADS patterns could potentially vary based on geographical location and institutional management and social structure also. The second limitation is that the study is confined only to post graduate students’ population. Therefore, the limited sample size restricts the generalizing outcomes to broader section of populations. Circadian cortisol variations further limit generalizability. Thirdly, research is confined to ADS, SC and Hb like psycho-physiological parameters among postgraduates, excluding age, gender and diverse exercises' effects. Fourth limitation is that the inadequate physiological assessment hinders direct correlation between ADS and serum cortisol and hemoglobin levels. Therefore, more substantial studies are needed for conclusive insights into pranayama's impact, including larger samples and encompassing yoga asanas, meditation and other yogic practices.

CONCLUSION

In fine, it can be stated that this study confirmed the positive impact of pranayama yogic breathing (PYB) on postgraduate students' well-being. PYB led to lower anxiety, depression and stress (ADS) scores, reduced cortisol levels and increased hemoglobin (Hb) levels. These results align with previous research and highlighted PYB's potential in enhancing mental and physical health. Therefore, Pranayama Yogic Breathing

(PYB) can be suggested as a most promising and potential means of alleviating ADS in Post Graduate students. However, further research is needed to explore its long-term effects and applicability in different populations, underscoring its value as a tool for wellbeing promotion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the dedicated faculty members and esteemed research scholars affiliated with the H.N.B. Garhwal A Central University. Their generous support and invaluable insights have greatly enhanced the quality of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declares that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Список литературы Effect of pranayama on anxiety, depression and stress levels in post-graduate students: correlation with serum cortisol and hemoglobin levels

- Abedi Amiri, M., Avandi, S. M., & Esmaeilzadeh, S. (2018). Effect of six-week pranayama training on the serum levels of cortisol and blood pressure in pregnant women in the third trimester. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility, 21(6), 55-63.

- Andrews, B., & Wilding, J. M. (2004). The relation of depression and anxiety to life-stress and achievement in students. British Journal of Psychology, 95(4), 509-521. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007126042369802

- Asif, S., Mudassar, A., Shahzad, T. Z., Raouf, M., & Pervaiz, T. (2020). Frequency of depression, anxiety and stress among university students. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(5), 971976. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.5.1873

- Balaji, P. A., & Varne, S. R. (2017). Physiological effects of meditation, yogasana and pranayama on stress scores and plasma cortisol levels among nursing staff of a multispeciality hospital. International Journal of Physiology, Nutrition and Physical Education, 2(1), 96-98

- Brown, R. P., & Gerbarg, P. L. (2005). Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 11(4), 711-717.

- Bryant, E. F. (2015). The yoga sutras of Patanjali: A new edition, translation, and commentary. North Point Press.

- Chandrababu, R., Kurup, S. B., Ravishankar, N., & Ramesh, J. (2019). Effect of pranayama on anxiety and pain among patients undergoing cardiac surgery: A non-randomized controlled trial. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 7(4), 606-610.

- Jagadeesan, T., R, A., R, K., Jain, T., Allu, A. R., Selvi G, T., Maveeran, M., & Kuppusamy, M. (2022). Effect of Bhramari Pranayama intervention on stress, anxiety, depression and sleep quality among COVID 19 patients in home isolation. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, 13(3), 100596. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjaim.2022.100596

- Jayawardena, R., Ranasinghe, P., Ranawaka, H., Gamage, N., Dissanayake, D., & Misra, A. (2020). Exploring the Therapeutic Benefits of Pranayama (Yogic Breathing): A Systematic Review. International Journal of Yoga, 13(2), 99-110. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJ0Y_37_19

- Jerath, R., Edry, J. W., Barnes, V. A., & Jerath, V. (2006). Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: Neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. Medical Hypotheses, 67(3), 566-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.042

- Kamei, T., Toriumi, Y., Kimura, H., Kumano, H., Ohno, S., & Kimura, K. (2000). Decrease in serum cortisol during yoga exercise is correlated with alpha wave activation. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 90(3), 1027-1032.

- Ma, X., Yue, Z.-Q., Gong, Z.-Q., Zhang, H., Duan, N.-Y., Shi, Y.-T., Wei, G.-X., & Li, Y.-F. (2017). The Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing on Attention, Negative Affect and Stress in Healthy Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2 017.00874

- Maheshkumar, K., Dilara, K., Ravishankar, P., Julius, A., Padmavathi, R., Poonguzhali, S., & Venugopal, V. (2022). Effect of six months pranayama training on stress-induced salivary Cortisol response among adolescents-Randomized controlled study. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 18(4), 463-466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2021.07.005

- Martínez-Líbano, J., Torres-Vallejos, J., Oyanedel, J. C., González-Campusano, N., Calderón-Herrera, G., & Yeomans-Cabrera, M.-M. (2023). Prevalence and variables associated with depression, anxiety, and stress among Chilean higher education students, post-pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.20 23.1139946

- Mirzaei, M., Yasini Ardekani, S. M., Mirzaei, M., & Dehghani, A. (2019). Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Adult Population: Results of Yazd Health Study. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 14(2), 137-146.

- Mofatteh, M. (2020). Risk factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression among university undergraduate students. AIMS Public Health, 8(1), 36-65. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2021004

- Novaes, M. M., Palhano-Fontes, F., Onias, H., Andrade, K. C., Lobäo-Soares, B., Arruda-Sanchez, T., Kozasa, E. H., Santaella, D. F., & Araujo, D. B. de. (2020). Effects of Yoga Respiratory Practice (Bhastrika pranayama) on Anxiety, Affect, and Brain Functional Connectivity and Activity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00467

- Premont, R. T., & Stamler, J. S. (2020). Essential role of hemoglobin ßCys93 in cardiovascular physiology. Physiology, 35(4), 234-243.

- Sahu, K. P., & Kishore, K. (2015). The effect of Bhramari Pranayama and Jyoti Dhyan effect on alpha EEG and Hemoglobin of college going students. Int Journal of Physical Education, Sports and Health, 1(4), 40-44.

- SAMHSA. (2021). Prevention and Treatment of Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among College Students. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory.

- Saraswati, S. S., & Hiti, J. K. (1996). Asana pranayama mudra bandha. Yoga Publications Trust Bihar, India.

- Satyananda. (2009). Asana pranayama mudra bandha (4. ed., repr). Yoga Publications Trust.

- Sengupta, P. (2012). Health Impacts of Yoga and Pranayama: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(7), 444-458.

- Shah, M. R., & Kothari, P. H. (2019). Effects of nadi-shodhana pranayama on depression, anxiety, stress and peak expiratory flow rate in post CABG patients: Experimental study. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 9(10), 40-45.

- Sharma, A., Khanna, V., Bhardwaj, A., & Raina, A. (2016). Role of nadi shuddhi pranayama on hypertension. Headache, 48(29), 39-58.

- Zaccaro, A., Piarulli, A., Laurino, M., Garbella, E., Menicucci, D., Neri, B., & Gemignani, A. (2018). How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2 018.00353

- Zada, S., Wang, Y., Zada, M., & Gul, F. (2021). Effect of mental health problems on academic performance among university students in Pakistan. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot, 23, 395-408.

- Zope, S. A., & Zope, R. A. (2013). Sudarshan kriya yoga: Breathing for health. International Journal of Yoga, 6(1), 4-10. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.105935