Effect of various doses of Cannabis extract on male reproductive system of FBV/N strain albino mice

Автор: Niladri Sekhar Das

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The experiment focused on the endocrinological, histopathological and biochemical effects of a Cannabis extract (CAN) containing cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa on the male reproductive system of mammals. The experiment involved five groups of albino mice (FBV/N strain), with 12 mice in each group. The groups were labeled as follows: CV-I, a control group treated with alcohol vehicle; CAN-II, a group treated with 40mg/mouse of CAN; CAN-III, a group treated with 60mg/mouse of CAN; CAN-IV, a group treated with 80mg/mouse of CAN; and CAN-V-R, a withdrawal group allowing for a 45-day recovery period after receiving 80mg/mouse of CAN treatment. The experimental subjects were given CAN through intraperitoneal injection. At low doses (40mg/mouse and 60mg/mouse), significant histopathological changes were observed, including a reduction in the weight of the testes, seminal vesicle, and epididymis, shrinkage of seminiferous tubules, impairment of the spermatogenic cycle, and a reduction in sperm count. There were also significant changes in protein, lipid, and cholesterol content, as well as in the concentration of steroidogenic enzymes such as 3-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), 17-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD), testicular acetylcholinesterase (tACHE), and testicular angiotensin-converting enzyme (tACE) at low doses. The reduction of 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD at low doses also affected the concentration of serum testosterone, supporting the higher value of cholesterol content. Additionally, a reduction in gonadotropins (FSH and LH) at low doses was documented, along with hypertrophied pituitary due to positive feedback stimulation. The reduction of lipid content was likely related to lipid peroxidation due to an increase in the amount of conjugated dienes. However, in the high-dose group (80mg/mouse) and the withdrawal group (CV-V-R), gradual recovery in all parameters was observed. In conclusion, it is suggested that high-dose CAN treatment produces a sort of stress that likely activates some stress-induced genes responsible for minimizing the drastic effects of CAN produced by low-dose treatment.

FBV/N strain adult male mice, Cannabis extract, Oxidative stress, free radicals, steroidogenic hormones

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143185132

IDR: 143185132

Текст научной статьи Effect of various doses of Cannabis extract on male reproductive system of FBV/N strain albino mice

Cannabis , also known as marijuana, is a psychoactive narcotic drug derived from the dried leaves, flowers, stems, and seeds of the hemp plant Cannabis sativa (Gaoni and Mechoulamm, 1964 Sharma et al ., 2012) . The people of Indian sub-continent have been using it for its psychoactive effects such as relaxation, euphoria, and altered perception, since ancient time. It is reported that male users of marijuana suffer from chronic infertility due to its disrupting effects on male reproductive system and hypothalamo-hypophyseal-testicular axis (Bari et al ., 2011; Mendelson et al ., 1974). Among all the derivatives of Cannabis extract (cannabinoids) obtained as fat soluble components from different parts of hemp plant, the most potent psychoactive principal is δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Dixit and Lohiya, 1975; De Zeeuw et al. , 1972). Additional research supports the idea that cannabinoids, have an inhibitory effect on the release of GnRH by interacting with CB1 and CB2 receptors. This leads to a decrease in the secretion of FSH and LH, which can significantly impact the male reproductive system (Gaoni and Mechoulamm,1964; Gye et al ., 2005). Cannabinoid receptors present on the testes, vas deferens, prostate epithelium, and spermatozoa`s acrosomal region, midpiece, and tail, suggest that Cannabis may disrupt spermatogenesis and sperm function (Lewis et al ., 2012 Aquila et al ., 2010; Agirregoitia et al ., 2010). It has been reported that cannabinoids causes testicular dysfunction and affects male fertility as measured by decreased level of testosterone in blood serum and sperm counts in rats including human beings (Mendelson et al . , 1974 Dixit and Lohiya, 1975). Altered male reproductive system with depressed testosterone level is seen after continuous use of marijuana, has been reported (Robert et al . 1974). High-dose Cannabis treatment in mice has been linked to testicular injury resulting from oxidativestress induced lipid peroxidation and the subsequent augmentation of antioxidant defense mechanism. (Mandal and Das, 2010). It is reported that testicular injury due to oxidative stress is comparatively more drastic than higher center injury (Mobisson et al ., 2022).

We have found that low doses of Cannabis extract can cause these adverse effects, but that high doses and recovery doses can activate antioxidant enzymes and help to mitigate the damage caused by the drug.

In this communication, we have investigated the histological, biochemical and endocrinological causes of the harmful effects of various doses of intraperitoneally administered Cannabis extract (CAN) on testicular function and impairment of spermatogenesis in Swiss albino mice strain FBV/N.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and solutions:

Cannabis extract, folin ciolteu reagent (FCR) solution, bovine serum albumin (BSA), Bouin`s fixative, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), β-NAD, Na-K tartarate, chloroform, Cyclohexane, Hippuric acid, testosterone RIA Kit was purchased from DiaSorin Diagnostic Division, CA, USA; Pituitary gonadotropins hormones such as follicular stimulating hor mone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) radio immunoassay kits were obtained from NIADDK, Bethesda, haematoxylin, eosin.

Preparation and purification of Cannabis extract from Cannabis sativa plant:

The active components of Cannabis sativa , are extracted using a method described by De Zeeuw et al . (1972) and Dixit et al . (1974). The extraction is carried out using 98% ethanol in a Soxhlet apparatus for 4-8 hours. The resulting extract is evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator under vacuum. The dried powder sample is then repeatedly extracted using fresh portions of light petroleum (40-60°C), followed by extraction with chloroform until extraction is complete. The completeness of the extraction is checked using thin-layer chromatographic examination of the extracts following the method of De Zeeuw et al . (1972).

Maintenance and feeding of Swiss Albino mice strain FBV/N:

Healthy Swiss Albino mice strain FBV/N, weighing between 25-30g, are bred and housed in standard polycarbonate cages in animal-based Physiology Research Laboratory of Belgachia Biophysics Division, Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, Kolkata. The mice are maintained under standard light and dark schedules (12

hours of light and 12 hours of darkness) controlled by a digital light timer. The temperature within the animal house is maintained at 22-25°C, and humidity is kept at 57% by using two dehumidifiers. The mice are fed a scientifically prepared balanced diet that contains crude protein (20-25%), crude fat (10-12%), carbohydrates (45-55%), crude fiber (4% or less), and casein (18%). Each cage, which houses six animals, is given 20g of diet per day per animal.

Treatment of active principals-cannabinoid (CAN) of Cannabis plant to mice:

The experiment uses adult male Swiss albino mice (FBV/N) that weigh around 30±3g. The Cannabis extract (CAN) is purified and evaporated to dryness. Then, the residue is weighed and redissolved in absolute alcohol. The CAN is then diluted and suspended in a vehicle mixture of ethanol polysorbate 20 saline (10 1 89 v/v) to achieve a final concentration of 10 mg/ml Cannabis extract (Dixit et al., 1974). The mice are divided into five groups, each consisting of 12 mice. Each group is treated with 0.2 ml of the stock vehicle mixed Cannabis extract, with a dose of 2 mg/mouse/day administered intra-peritoneally(Table 1) (Dixit et al ., 1974; Mondal and Das, 2010).

The body weight alterations in mice subjected to CAN treatment are assessed daily prior to commencing the treatment and meticulously documented. Upon completion of the final measurements for each treatment group, the animals are anesthesized under light ether. Decapitation is performed by severing the head to expose the carotid artery for blood sample collection following the Institutional Animals Ethics Guidelines. The right testes, pituitary gland, epididymis, and seminal vesicles of treated mice are weighed and preserved for standard histological examinations, while the left testes are weighed and stored at -20°C for biochemical and hormonal analyses.

Histological studies of testes:

The right testis of each mouse was placed in Bouin’s fixative solution immediately after removal and left overnight for histological analysis. Afterward, the tissue underwent dehydration using graded alcohol solutions and was processed for paraffin embedding. The embedded blocks were then sectioned to a thickness of

5 to 7µm using a rotary microtome (Leica, Germany). These sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined under an optical microscope at various magnification levels (100×, 220×, and 320×). Images were captured at 220× magnification using a Leica optical microscope equipped with an MPS photographic system for the evaluation of histomorphological and histometric characteristics.

Measurement of seminiferous tubular diameter and extent of shrinkage:

To measure tubular shrinkage, slides are stained and placed under a high power objective in a phase contrast microscope. About 10 randomly selected seminiferous tubules (round or oval-shaped) are then observed from sections of each testis of an individual rat, and their diameter is noted. This is done by taking the margin lines of the tubules (upward, downward, left and right sides) from each slide. The diameter of seminiferous tubules, their lumen, and the extent of their shrinkage (in micrometers) are measured.

Determination of relative number of tubules containing healthy and degenerated germ cells:

To analyze the effect of Cannabis extract on the testis, a minimum of 20 random tubules from each individual's testis are examined. The tubules are inspected under a magnification of 320× to count the number of tubules that contain healthy and degenerated germ cells and identify the occurrence of spermatogenesis. The mean value is then expressed as a percentage. Additionally, cytological examination of various stages of germ cells is performed to determine any histomorphological changes that may have occurred due to the exposure to Cannabis extract.

Cytological study of seminiferous tubules and study of spermatogenesis:

A quantitative analysis of spermatogenesis entails counting the relative abundance of each type of germ cell at stage VII of the seminiferous epithelium, namely type A spermatogonia (ASg), mid-pachytene spermatogonia (mPSc), and stage 7 spermatids (7Sd) (Abercrombie, 1946; Clermont and Morgentaler, 1955). The counts of germ cells at stage VII of the seminiferous spermatogenic cycles serve as indicative markers of treatment-related lesions. Theoretically, each primary spermatocyte undergoes two successive reduction divisions to yield four spermatids. Hence, the mPSc to 7Sd ratio is expected to be 1 4. The percentage of 7Sd degeneration is derived from this ratio.

Sperm count of drug treated mice:

Sperm count is assessed using a hemocytometer (Chatterjee et al ., 1988). Samples are collected from the cauda epididymis immediately post-mortem. The cauda epididymis is submerged in a small beaker containing 5ml of 1% (w/v) fructose or glucose in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). A fine hypodermic needle punctures the cauda, and the spermatozoa are rinsed with diluents. Gentle shaking of the beaker ensures homogeneous spermatozoa concentration. A drop of the suspension is then placed on the hemocytometer and covered with a cover glass. This process is repeated at least five times for each sample obtained from individual animals.

RIA for serum testosterone:

For plasma testosterone hormone assay, fresh blood is collected into a heparin coated vacuum tube. After separation by low-speed centrifugation (at ×800 g) using clinical cold centrifuge, the plasma testosterone level is measured by using Immunochem TM coated tube Testosterone125I RIA Kit supplied by DiaSorin Diagnostic Division CA, U.S.A.

Study of 3β – and 17β – hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity:

The activities of 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD were estimated spectrophotometrically following the procedures established by Talalay (1962) and modified by Jaraback et al. (1962). Testis tissue was homogenized in glycerol solution with 5nmol potassium phosphate and 1mmol EDTA at a concentration of 100mg ml-1 homogenizing mixture, then centrifuged at 10000g for 30mins at 4oC. to measure 3β-HSD activity, 1ml of the supernatant was mixed with 1ml of sodium pyrophosphate buffer (pH 8.9), 40 µl of 0.3mmol dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and 960µl of 0.025% bovine serum albumin (BSA) to make a 3ml incubation mixture after which the addition of 0.5µmol of oxidized β-NAD allowed absorbance to be recorded at 340nm against a blank (without NAD), with one unit of enzyme activity defined as a change in absorbance of 0.001 per minute. For 17β-HSD activity, the same procedure was followed, but 40µl of 0.3mmol testosterone was used as the substrate instead of DHEA.

Estimation of protein, lipid and phospholipid content:

The protein estimation of testicular tissue sample is carried out according to the Lowry et al ., (1951). To estimate protein content using the Lowry method, aliquots of standard BSA protein (5 to 100 micrograms) and diluted testicular tissue samples (at a ratio of 1 20) are prepared in test tubes. A 5ml alkaline copper solution, formed by mixing 50ml of 2% Na 2 CO 3 solution in 0.1% 1N NaOH with 1ml of 0.5% CuSO 4 in 1% Na-K-Tartarate solution, is added to each tube. After 10 minutes in the dark, 0.1ml of Folin-Ciocalteu solution is added, and the mixture is allowed to sit for 30 minutes, resulting in a blue color. Protein content is estimated by measuring absorbance at 750nm using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer, with a standard calibration curve prepared using BSA absorbance data.

To extract total lipids from testicular tissue according to Floch et al ., (1957), fresh tissue (0.8-1.2 grams) is homogenized with 2ml Tris HCl buffer and an equal volume of TCA solution is added in homogenate, then left for 30 minutes. After adding 10ml chloroform methanol (2 1 v/v) and incubating for 3-4 hours, 0.5M DPTA is added and centrifuged. The resulting supernatant and pellet are dissolved in chloroform methanol water (2 1 8 v/v) and incubated overnight with N 2 flushing. The lower chloroform layer, enriched with lipids, is isolated, treated with 2M KCl, and incubated for 3-4 hours. The lower chloroform-soluble lipids are collected, vacuum dried, and dissolved in chloroform.

Phospholipid is isolated from the total lipids fraction by repeated precipitation with the ice cold acetone (Lipsky et al., 1957; HsuChen and Feingold, 1973). 0.81.0gm of testicular tissue, is homogenized in 20ml of water followed by the addition of 20ml of 10% TCA (w/v) to the homogenate and centrifuge at 5000 r.p.m. for 30 minutes. The precipitate after mixing with 75ml of a methanol-chloroform mixture (2 1, v/v), vigorously shaken and allowed to sit at room temperature in a nitrogen atmosphere overnight, followed by filtration. The filtrate is resuspended in 95ml methanol-chloroform-water (2 1 0.8 v/v), filtered again, and washed 3 times with 2M KCl. Collect the lower chloroform phase, add an equal volume of water, and shake. Leave the mixture overnight at room temperature in a separating funnel. Finally, collect the lower chloroform phase of the liquid, dry it under vacuum, and dissolve it in chloroform under a nitrogen atmosphere. Seperation is done by silicic acid column chromatography (Lea et al., 1966)

Extraction, purification and Estimation of cholesterol:

A testicular tissue sample is immersed in 5ml solution of alcohol-acetone (1 1) in a 10ml volumetric flask and boiled before cooling. After making upto the mark with alcohol-acetone, filtrate and 5ml of filtrate is mixed with 0.15ml of KOH solution and incubated for 40 minutes at 37-40oC. Phenolphthalein is added, and titration with 10% acetic acid in absolute alcohol follows. The solution is then evaporated and cooled, and 0.1ml of 50% alcohol is added. The mixture is washed with petroleum ether multiple times, decanting carefully. The combined extracts are evaporated to dryness, ensuring complete removal of solvents. If needed, absolute alcohol is added for further drying.

Estimation and development of colour of the cholesterol component for quantification of cholesterol:

In a dark cabinet, a water bath at 24°C is maintained, with adjustments made using hot or cold water as necessary. Bottles containing dried tissue extract are pipetted with 5 cc of acid-free chloroform, along with 5 cc portions of standard solutions containing 0.24, 0.4, and 0.6 mg of pure cholesterol in chloroform, then placed in a water bath. A glass-stoppered container is used to prepare 20 cc of pure acetic anhydride with 1 cc of concentrated sulfuric acid, chilling it in an ice bath. Samples are taken out at intervals, reacted with the reagent, and returned to the bath. Color development is timed and read against a standardized dye solution in a calorimeter (Sperry et al ., 1943).

Assay of conjugate dienes of testicular lipids:

Testicular tissue is homogenized in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at a concentration of 50 mg/ml. Lipids are extracted from the homogenate (0.5 ml) using a chloroform-methanol mixture (2 1, v/v) and centrifuged at 1000g for 5 minutes at room temperature. The chloroform is then evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, and the lipid residue is dissolved in 1.5ml of HPLC-grade cyclohexane. The absorbance of the resulting conjugated diene is measured spectrophotometrically at 215 and 233 nm, with the conjugated diene content expressed as nanomoles per milligram of tissue. (Slater, 1984a; Slater, 1984b).

Estimation of testicular Acetylcholinesterase enzyme and Angiotensinogen converting enzyme (ACE):

A 400µl of aliquot of testicular tissue homogenate (approximately 20mg of tissue in 1ml phosphate buffer, pH 8.0) is added to a cuvette containing 2.6ml of phosphate buffer (0.1M, pH 8.0), then 100µl of DTNB is added to the cuvette and the absorbance is measured at 412nm. 20µl of acetylcholine iodide is added to show changes in absorbance and record the absorbance is noted and the change in absorbance per minute is calculated. For estimation of ACE 0.1ml of 10% (w/v) tissue homogenate is added to 0.3ml of incubation medium containing 5mM Hippuryl-L-Histidyl-L-Leucine, 300mM NaCl, 100mM Potassium phosphate buffer ( pH 8.3) and various concentration of enzymatic proteins and incubated at 37oC for 30 minutes. The reaction is stopped by adding 5ml of 1N HCl. The hippuric acid is extracted with 2.5ml of ethyl acetate by vortex mixing for 90 seconds. 1ml of extract is taken up in 5ml of distilled water. The hippuric acid concentration is determined by measuring the absobance of 228nm against zero time blank prepared by adding 1N HCl before the enzyme. The enzymatic activity is found to be linear with protein concentration and incubation time (Cushman and Cheung, 1971; Jaisawal et al ., 1984).

Statistical analysis:

The data are expressed as mean ±SEM. For statistical analysis, the quantitative data of each parameter from the different groups are analyzed by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a two tail “t” test followed by post hoc test. Significance are set at p<0.05. All calculation have done by Microsoft excel 2016 version.

RESULTS

Body weight, seminal vesicles, epididymis and testicular weight changes:

During the study, none of the mice treated with Cannabis extract (CAN) at varying doses exhibited signs of mortality or morbidity. Although there were no significant changes in the initial body weight of the CAN-treated mice compared to the control group (CV-I), a notable decrease in testicular mass was observed. Specifically, the weight of the testes showed significant reduction at lower doses (40mg/mouse and 60mg/mouse) in the CAN treatment groups (CAN-II and CAN-III). However, at a higher dose (80mg/mouse) and during the withdrawal period of 45 days (CAN-IV and CAN-V-R), a gradual recovery of testicular weight was observed. The weights of seminal vesicles and epididymis were significantly altered at lower doses, indicating potential effects of CAN treatment (Table 2).

Histometric studies on shrinkage of seminiferous tubules:

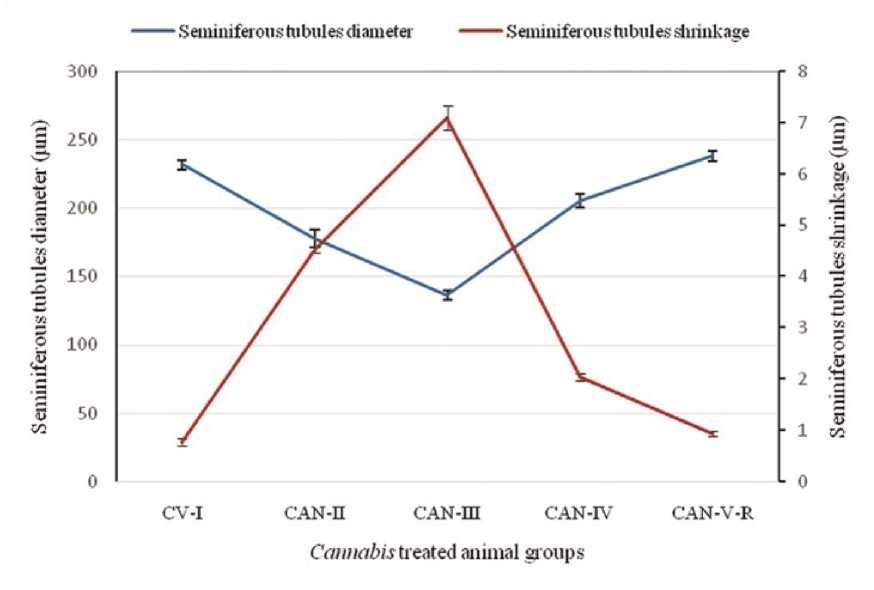

Histological examination as part of the routine process revealed significant shrinkage of the seminiferous tubules at low doses (CAN-II and CAN-III) compared to the control vehicle-treated group CAN-I, where seminiferous tubules remained compact without any interstitial or intercytoplasmic spaces within germ cells. The most pronounced shrinkage of testicular tubules was observed in CAN-III animals. The reduction in seminiferous tubular diameter at low dose (60mg/mouse) led to increased spacing within the germ cells. Serious damages to the laminar basement membrane were noted in conjunction with the shrinkage of seminiferous tubule diameter (Table 2) (Figure 1).

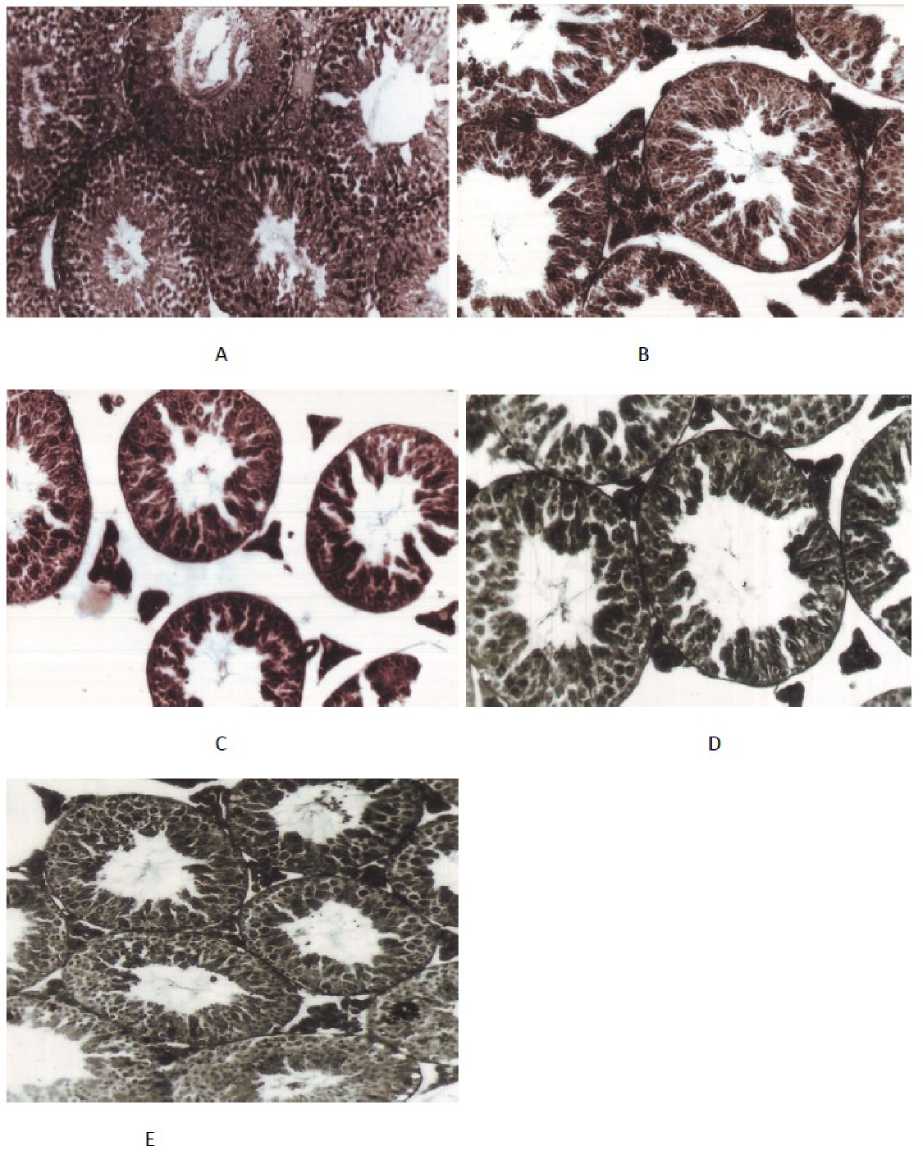

Cytological changes of germ cells of testes:

Histological analysis also reveals that following treatment with CAN-drug (at total doses of 40mg and 60mg per mouse), there is a noticeable reduction in the number of spermatogonia. Common occurrences of cytolysis and chromatolysis are observed, accompanied by a decrease in spermatozoa count. Particularly, after treatment with a total dose of 60mg per mouse, there is a complete arrest of spermatogenesis. The cytoplasm appears scanty, and the nuclei are shrunken, indicating detrimental changes in the germinal epithelium following drug treatment, especially at the total dose of 60mg (CAN-III). However, the effects are less pronounced at higher doses (CAN-IV) and after a 45-day withdrawal period following high-dose drug administration (80mg/mouse) (CAN-V-R).

Furthermore, in the CAN-IV group, the diameter of the tubules is slightly distended compared to that of the control vehicle-treated group (CV-I). Significant recovery effects on the germ cell layers with regression of seminiferous tubules in the testes (though not returning to normal) are observed in the higher dose group (CAN-IV) and withdrawal group (CAN-V-R). Complete recovery of spermatogenesis and testicular cell function is noted in mice after a 45-day withdrawal period from the drug, although testicular weight is not fully restored (Figure 2).

Spermatogenic cell cycle changes:

In the testes treated with the control vehicle, the seminiferous tubules appear tightly packed, containing a thick, multilayered germinal epithelium with various stages of spermatogenic cells and distinct clusters of mature spermatozoa. However, in the low-dose groups (CAN-II and CAN-III), there is a noticeable decrease in the number of spermatogonia, with the presence of pachytene spermatocytes exhibiting pycnotic chromatids. Quantitative cytological analysis of germ cells at stage VII of the seminiferous epithelium cell cycle reveals that CAN treatment at low doses particularly at 60mg/mouse (CAN-III) leads to a significant reduction in type A spermatogonia (ASg), preleptotene spermatogonia (pLSc), mid-pachytene spermatogonia (mPSc), and stage 7 spermatids (7Sd) compared to the control group. However, at higher doses, detrimental effect of CAN is less and there is a remarkable recovery, nearly approaching levels observed in the control group (Table 3).

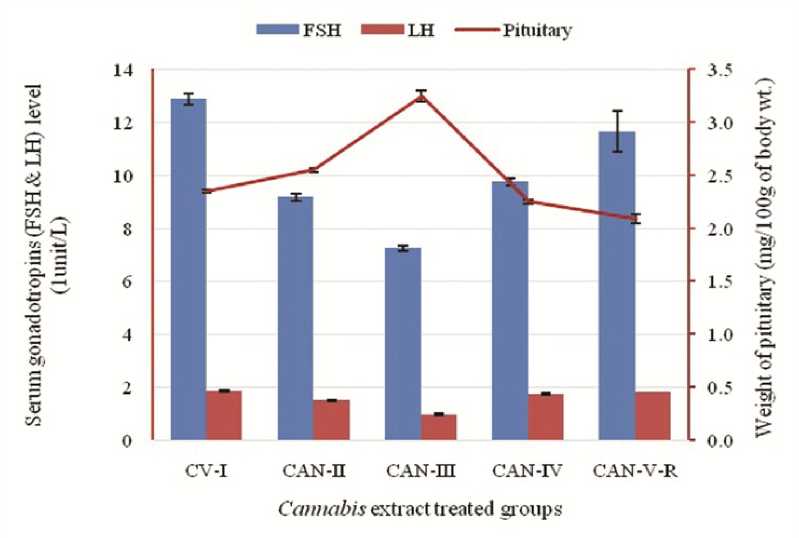

Cannabis-induced serum hormonal profile changes:

Substantial alterations and a marked decrease in plasma testosterone and gonadotropins concentration are evident primarily at low doses (CAN-II and CAN-III). Conversely, at higher doses (CAN-IV), the impact is less pronounced, with some indications of resurgence in plasma testosterone and pituitary gonadotropins like FSH and LH. This trend is similarly noted in CAN-V), where a period of 45 days post-treatment cessation of the drug at an 80mg total dose reveals a comparable effect. Interestingly, the pituitary gland exhibited increased weight at lower doses, suggesting hyperactivity at those levels (Table 4) (Figure 3).

Table 1. Experimental design for the treatment with Cannabis extract to the FBV/N strain mice (n=12).

|

Group |

Treatment description |

ml/ mouse |

mg/ mouse |

Days |

For recovery (days) |

Total dose (mg/mouse) |

Group name |

|

I |

Alcohol vehicle treated mice (Control) |

0.2 |

- |

40 |

- |

- |

CV-I |

|

II |

CAN treated |

0.2 |

2.0 |

20 |

- |

40 |

CAN-II |

|

III |

CAN treated |

0.2 |

2.0 |

30 |

- |

60 |

CAN-III |

|

IV |

CAN treated |

0.2 |

2.0 |

40 |

- |

80 |

CAN-IV |

|

V |

CAN treated + kept animal for recovery |

0.2 |

2.0 |

40 |

45 |

80 |

CAN-V-R |

Table 2. Change of body weight and other male reproductive parameters of FBV/N albino mice strain after treating with Cannabis extract (CAN) at different doses. (n=12). (Value are mean ± S.E. of 12 animals in each group. The CAN groups are compared with control vehicle group, CV-I)

|

Animal Groups |

Body wt. (g) |

Testes wt. (mg/100g body wt.) |

Seminal vesicle (mg/100g body wt.) |

Epididymis (mg/100g body wt.) |

Seminiferous tubular diameter (µm) |

Extent of tubular shrinkage (µm) |

|

CV-I |

31.09±0.34 |

660.12±6.28 |

472.62±9.81 |

400.25±2.26 |

231.88±0.98 |

0.77±0.02 |

|

CAN-II |

30.27*±0.19 |

473.79*±1.98 |

450.87*±5.38 |

362.48*±3.40 |

177.76*±1.93 |

4.52*±0.02 |

|

CAN-III |

26.94*±0.25 |

453.88*±2.41 |

323.16*±8.98 |

271.09*±2.25 |

136.49*±1.08 |

7.10*±0.07 |

|

CAN-IV |

32.40*±0.33 |

520.74*±6.06 |

349.48*±5.52 |

310.69*±2.28 |

205.48*±1.40 |

2.04*±0.02 |

|

CAN-V-R |

34.77*±0.29 |

555.38*±4.95 |

460.18*±6.28 |

450.58*±2.10 |

238.19*±1.20 |

0.93*±0.01 |

*P<=0.05 compared with CV-I, Post-hoc ANOVA test has been done.

Table 3: Effect of Cannabis extract (CAN) on spermatogenesis at stage VII of the seminiferous epithelium in albino male mice (FBV/N strain). ASg, type A spermatocytes; pLSc, preleptotene spermatocytes; mPSc, mid-pachytene spermatocytes; and 7Sd, stage 7 spermatids. n=12. Value are mean ± S.E. of 12 animals in each group.

|

CAN treated groups |

Relative number of germ cells per tubular cross section of the testis |

Ratio-mPSc 7Sd |

Sperm count (106/cauda epididymis) |

|||

|

ASg |

pLSc |

mPSc |

7Sd |

|||

|

CV-I |

0.64±0.056 |

21.90±0.53 |

23.80±0.49 |

69.20±0.34 |

1 2.9 |

157.25±8.89 |

|

CAN-II |

0.453*±0.097 |

14.99*±0.265 |

11.86*±0.152 |

30.46*±0.564 |

1 2.57 |

120.16*±3.59 |

|

CAN-III |

0.357*±0.016 |

12.37*±0.275 |

9.76*±0.145 |

20.42*±0.352 |

1 2.09 |

90.72*±2.45 |

|

CAN-IV |

0.706*±0.082 |

21.82*±0.328 |

20.32*±0284 |

61.81*±0.513 |

1 3.04 |

110.25*±2.78 |

|

CAN-V-R |

0.66*±0.045 |

22.034*±0.372 |

24.27*±0.83 |

71.87*±0.141 |

1 2.96 |

137.18*±3.62 |

*p<0.05 compared with vehicle treated control (CV-I) group as based on statistical analysis by Post-hoc ANOVA test.

Table 4. Effect of Cannabis extract (CAN) on testosterone, gonadotropins (FSH & LH) and pituitary in albino mice, FBV/N strain (n=12). Value are mean ± S.E. of 12 animals in each group. The CAN groups are compared with control vehicle group, CV-I.

|

CAN treated groups |

Serum Testosterone (ng/ml) |

Serum FSH (1U/L) |

Serum LH (1U/L) |

Pituitary (mg/100g body wt.) |

|

CV-I |

2.39±0.04 |

12.87±0.22 |

1.86±0.04 |

2.35±0.013 |

|

CAN-II |

1.51*±0.09 |

9.18*±0.13 |

1.50*±0.02 |

2.55*±0.019 |

|

CAN-III |

1.35*±0.03 |

7.24*±0.11 |

0.97*±0.03 |

3.25*±0.051 |

|

CAN-IV |

1.75*±0.02 |

9.76*±0.77 |

1.74*±0.03 |

2.09*±0.019 |

|

CAN-V-R |

2.14*±0.04 |

11.66*±0.14 |

1.81*±0.01 |

2.25*±0.036 |

*p<0.05 compared with vehicle treated control (CV-I) group as based on statistical analysis by Post-hoc ANOVA test.

Table 5 . Effect of Cannabis extract (CAN) on biochemical parameters in albino mice, FBV/N strain (n=12). Value are mean ± S.E. of 12 animals in each group. The CAN groups are compared with control vehicle group, CV-I.

Table 6 . Effect of Cannabis extract (CAN) on testicular acetylcholinesterase (tACHE) and testicular angiotensin converting enzyme (tACE) in albino mice, FBV/N strain (n=12). Value are mean ± S.E. of 12 animals in each group. The CAN groups are compared with control vehicle group, CV-I.

Figure 1: Effect of Cannabis extract on seminiferous tubules diameter and extent of shrinkage in adult male albino mice (FBV/N strain). CAN-III shows the maximum shrinkage of seminiferous tubule, where as in high dose i.e., CAN-IV this shrinkage is minimized. Values are mean ± S.E.M. of 12 mice in each group. (P<0.05)

Figure 2: Photomicrograph (magnification × 220, H & E stained) of transverse section of Cannabis extract treated mice testes with control as well as various doses of drug. (A) T. S. of alcohol vehicle treated mice testis (CV-I) showing germinal epithelial layer of seminiferous tubules appear tightly packed, with various stages of spermatogenic cells; (B) T.S. of total of 40mg (CAN-II) Cannabis extract treated mice testis shows noticeable decrease in the number of spermatogenic and germ cells with degenerated germinal epithelium; (C) T.S. of mice testis treated with total of 60mg Cannabis extract per mice (CAN-III) shows detrimental changes in the germinal epithelium, shrinkage of seminiferous tubules with scanty cytoplasm and shrunken nuclei; (D) T.S. of testis treated with 80mg per mice (CAN-IV) Cannabis extract shows restoration of normal diameter of seminiferous tubule with compactness due to recovered healthy epithelium and germinal cell layers; (E) T.S. of testis of mice treated with total dose 80mg per mice plus withdrawal of drug for another 45 days per mouse (CAN-V-R) shows recovery effect.

Figure 3: Effect of Cannabis extract on plasma gonadotropins (FSH and LH) and weight of pituitary in adult male albino mice (FBV/N strain). Values are mean ± S.E.M. of 12 mice in each group. Here decline concentration of gonadotrpins and as a result pituitary hypertrophy due to positive feedback effect is prominently seen at the dose of 60mg/mouse but at the higher dose gradual increment of gonadotropins is concomitantly related with the achieving of normal weight of pituitary. P<0.05 for each bar diagram and linear diagram as compared to the control alcohol vehicle treated animal (CV-I)

Cannabis extract treated animal groups

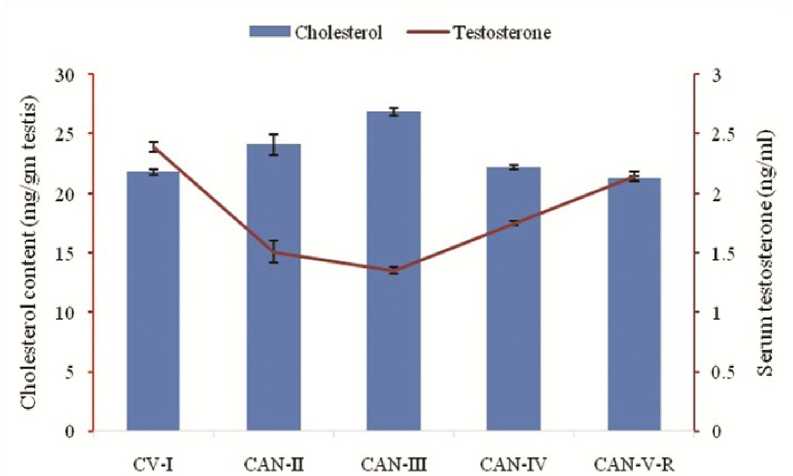

Figure 4: Correlation between the effect of Cannabis extract on cholesterol content and serum testosterone concentration in adult male albino mice (FBV/N strain). Values are mean ± S.E.M. of 12 mice in each group. In low dose group (60mg/mouse) it is clearly visualized that rising cholesterol level is associated with diminishing testosterone level. P<0.05 for each bar diagram and linear diagram as compared to the control alcohol vehicle treated animal (CV-I).

M3HSD —1'HSD ---Testosterone

CV-I CAN-n CAN-Ш CAN-IV CAN-V-R

Cannabis extract treated animal groups

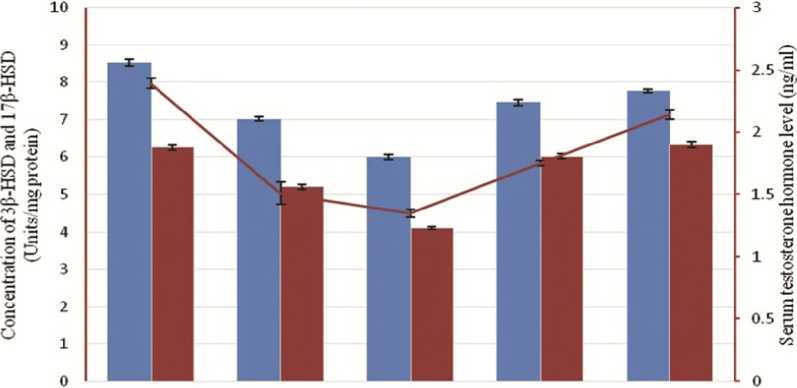

Figure 5: Correlation among the effect of Cannabis extract on testicular steroidogenic enzymes – 3-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) and 17-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) along with testosterone in adult male albino mice (FBV/N strain). Values are mean ± S.E.M. of 12 mice in each group. Subtle declination of the concentration of two major steroidogenic enzymes along with their ultimate product, testosterone, is clearly noticed at low dose (60mg/mouse). P<0.05 for each bar diagram and linear diagram as compared to the control alcohol vehicle treated animal (CV-I). Enzyme activity is expressed as 1 Unit of enzyme activity which is the amount causing the change in absorbance of 0.001 Unit/min using steroid as substrate.

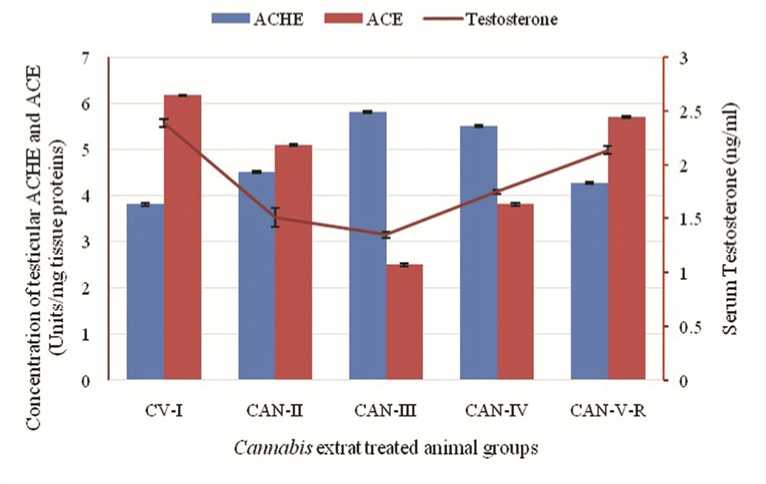

Figure 6: Correlation among the effect of Cannabis extract on concentration of testicular ACHE and ACE and serum testosterone concentration in adult male albino mice (FBV/N strain). Values are mean ± S.E.M. of 12 mice in each group. Severe effects on low dose group (60mg/mouse) are also documented here with the rising level of tACHE along with diminishing level of tACE and serum testosterone. P<0.05 for each bar diagram and linear diagram as compared to the control alcohol vehicle treated animal (CV-I).

Biochemical changes: injury to testicular lipids, proteins, cholesterol and conjugated dienes:

According to the biochemical analysis, administering CAN at low doses (CAN-II and CAN-III) leads to noteworthy reductions in lipid and protein levels in albino male mice compared to those treated with the control vehicle (CV-I). However, this effect is less pronounced in animals receiving higher doses and those undergoing drug withdrawals. A significant change is observed in the testicular cholesterol content, with the low-dose group receiving 60mg/mouse (CAN-III) exhibiting an increase in cholesterol levels. Furthermore, diene conjugate levels gradually increase with lower-dose treatment compared to higher doses (Table 5).

Effect of Cannabis extract on 3-β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and 17-β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase:

At low dose 3-β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3-β-HSD) and 17-β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17-β-HSD) decreases, whereas at higher dose shows recovery effect to some extent (not same as to the noramal level). Withdrawal shows recovery effect (Figure 5).

Effect on testicular ACHE and testicular ACE:

Biochemical analysis reveals that CAN treatment at low doses (CAN-II and CAN-III) leads to significant increases in testicular Acetylcholinesterase (tACHE) activity compared to albino male mice treated with the control vehicle (CV-I). However, this elevation is less pronounced in animals receiving higher doses and those undergoing drug withdrawal. A notable change in testicular Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (tACE) content is observed, with ACE activity gradually decreasing in low-dose groups. High-dose treatment (80mg/mouse) exhibits signs of ACE activity restoration, while the withdrawal group shows some degree of recovery, albeit not to the extent seen in the CV-I group (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

FBV/N mice strain treated with Cannabis extract shows alarming histo-architectural condition due to reproductive toxicity with the loss of testicular and epididymal weight, augmentation of testicular atrophy, severe damages to the basement membrane and shrinkage of diameter of seminiferous tubules (Figure 1). CAN drug initiates drastic damages to the several cell layers of seminiferous tubules. At low doses (CAN-II and CAN-III) type A spermatogonia (ASg), mid-pachytene spermatogonia (mPSc), and stage 7 spermatids (7Sd) shows sharp decline with maximum degeneration of spermatid at the dose of 60mg per mouse (CAN-III) (Table - 3) (Figure 2) and for this reason sperm count is significantly lowered at this dose that is, 90.72±2.45 million/cauda epididymis in comparison to the vehicle treated group (157.25±8.89 million/cauda epididymis) (P<0.05). It is very much interesting to notice in this context that at high doses group (CAN-IV) and 45 days withdrawal group (CAN-V-R) the effect in all parameters are comparatively lessened due to the presence of natural internal defense mechanism (Mandal and Das, 2010). Moreover at the withdrawal dose the damages more or less recovered though not alike control vehicle group with slight distended seminiferous tubules.

Spermatogenesis with the formation of healthy germ cells within testes and maturation of these cells in epididymis is totally under control of hormones, specially testosterone, FSH and LH. With this correlation it is assumed that the atrophied and degenerative architecture of seminiferous tubules with its collapsed spermatogenic cell layers is positively related with reduces testosterone, FSH and LH hormonal level in low dose CAN treated group (Table-4). Reduction in serum testosterone, the primary male sex hormone of mammals, and gonadotropic hormones, FSH and LH, is one of the main causes for the cessation of spermatogenesis and testicular degeneration (Figure 3). Testicular degeneration with massive cellular destruction, damage epithelium, and reduced germ cell count is also correlated with the reduction of testicular lipid content in low dose group (CAN-II and CAN-III). Lowering the lipid content in testicular tissues in low dose groups is due to maximize lipid peroxidation which is documented with the significantly increased of diene conjugates (162.44±3.08 nmol/mg tissue in CAN-II and 173.68±3.65 nmol/mg tissue in CAN-III) (P<0.05) (Table-5). At low dose (CAN-II and CAN-III) the augmentation of cholesterol level is presumably associated with the impairment of testosterone synthesis. In CAN-II and CAN-III groups the cholesterol level are increased significantly (P<0.05) in comparison to the vehicle treated group, CV-I whereas in these two groups (CAN-II and CAN-III) the testosterone levels are lowered significantly (P<0.05) (Figure 4). It is quite interesting that at high dose e.i., 80mg per mouse CAN treatment (CAN-IV) group the level of androgenic hormone and gonadotropins are more or less recovered, even the extent of lipid peroxidation is minimized with the documentation of lowering cholesterol amount and higher testosterone level along with lower conjugated dienes level. Significant reduction of testosterone hormone level in low dose drug treatment group may be correlated with the concomitant reduction of two major enzymes in Leydig cells, namely 3-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) and 17-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD). At the low dose (CAN-II and CAN-III) the enzymes are significantly low in concentration in comparison with CV-I (P<0.05), which indicates the inhibitory effect on testosterone synthesis due to the concomitant reduction of these two enzyme levels and thereby affects spermatogenic cycle drastically (Figure 5). But at high dose drug treatment and also at withdrawal dose recovery of these two enzymes is very much conspicuous to be observed, probably due to the rejuvenation and arousal of antioxidant defense mechanism.

The concurrent reduction of lipid and increased lipid peroxidation at low doses occurs due to oxidative stress induced by CAN induced free oxygen radicals (Mondal and Das, 2010 ). Lower dose of CAN treatment (CAN-II and CAN-III) is more responsible for the production of more free radicals as well as oxidative stress which is the main cause of testicular degeneration, impairment of testicular hormone synthesis, inhibition of spermatogenesis. In our previous research (Mondal and Das, 2009, 2010) we prove that to combat with such oxidative stress, an array of enzymes are synthesized to constitute the antioxidant defense system, which is not sufficient at low dose group (CAN-II and CAN-III) to protect the tissues from the malicious effect of oxidative stress, but at the high dose and 45 days recovery dose, probably at a certain threshold level of reactive oxygen radicals, a triggering effect is switched on to synthesis higher level of antioxidative enzymes like SOD, Catalase and glutathione peroxidase which take the responsibility to scavenge the radicals (Mondal and Das, 2010 ). From this point of view it is observed that the degree of the production of antioxidant enzymes and its defense mechanism is strongly correlated with a threshold level of oxidative stress. As in low dose treated group (CAN-II and CAN-III) drug induced oxidative stress do not achieve that threshold line, sufficient amount of antioxidative enzymes do not produced to protect the menace. So, heavy tissue damage is significantly noticed in these two groups. The failure of enzyme synthesis is evidenced with the documentation of lower testicular tissue protein content at low dose groups (CAN-II and CAN-III) in comparison with control vehicle treated group (CV-I) (Table-5). But at high dose group (CAN-IV) and withdrawal group (CAN-V-R) the protein content gradually achieve its normal levels in comparison to control group and thereby indicates the enhancement of antioxidative enzyme synthesis (Table 5).

Research emphasizes the crucial role of testicular angiotensin-converting enzyme (tACE) expression by Leydig cells in testicular steroidogenesis (Douglas et al., 2004) highlighting its importance in male reproductive function. Additionally, the presence of ACE in the testes implies its involvement in key aspects of male fertility, with normal spermatozoa potentially secreting tACE to enhance fertilizing ability. Testicular ACE activity indirectly influences sperm motility, likely through interactions with the renin-angiotensin and kallikrein-kinin systems (Shibahara et al., 2001). Studies indicate a positive correlation between tACE expression, particularly in the neck and mid-piece regions, and sperm motility (Pencheva et al., 2012).). Localization of ACE in post-meiotic spermatids and ejaculated spermatozoa (Pauls et al., 2003), even on sperm head, midpiece and flagellum (Kohn et al., 1998) suggests its role in sperm function probably on its motility. At low doses, particularly at 60mg dose (CAN-III) the decreased quantity of tACE might be correlated with the lowering level of testosterone synthesis and sperm count in epididymis. On the other hand decreasing tACE level at low doses gradually diminishes the fertile potentiality of male animals due to seriatim lack of motility of spermatozoa. At high and withdrawal dose the reestablishment of tACE concentration is observed with indicates the slow but steady recovery of testicular steroidogenesis and healthy testicular and epididymal microenvironment to produce healthy and motile spermatozoa (Table-6).

The non-neuronal cholinergic system consists of acetylcholine, acetylcholinesterase, and their transporter and receptors are distributed in spermatogonia, spermatids, seminiferous tubules, even within Sertoli cells, which indicates a potentially important role of testicular ACHE (tACHE) in germ cell production and differentiation (Schirmer et al ., 2011). In testicular tissue Acetylcholinesterase (ACHE) though increases germ cell apoptosis but augment spermtazoa motility (Mor et al ., 2008) With the cannabinoid drug treatment it is clearly observed that at low doses (CAN-II and CAN-III) germ cell epithelium within seminiferous tubules has been largely diminished and one of its reasons might be due to the increment of tACHE activity within the testicular tissue which is supported by our observation. Another interesting obserbvation is that as tACE level is lowered at low dose mice group and for what sperm motility are minimized, greater value of tACHE in these groups probably play a role to enhance sperm motility (Figure 6).

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the present study shows extract of Cannabis plant i.e., cannabinoids causes serious damage to the male reproductive system, histopathologically, biochemically and endocrinologically when administered intrperitoneally. But extent of damage is mostly caused at low doses probably due to excessive production of oxidative stress and super oxide radicals which are not ameliorated by the low production of antioxidants. But at high dose due to activation of some genes, augmentation of defense mechanism helps to manage amelioration. Probably a threshold level of oxidative shock is required to trigger the activation of these genes. Here farther research is needed to find out such stress shock genes, but through our experiment, the presence of such genes is speculated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Tapas Kumar Mondal, Associate Professor, Biophysics Division, Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, Kolkata, West Bengal, India, for his invaluable guidance throughout this study. His insightful feedback and expertise were instrumental in shaping this research. I would also like to thank Biophysics Division of Saha Institute Nuclear Physics for providing access to necessary resources.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author declare that she has no conflicts of interest.