Efficacy of spermine foliar application in delaying senescence of the fourth youngest leaf in wheat

Автор: Nemat M. Hassan, Heba T. Ebeed, Hanan S. Ali

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The objective of this study is to elucidate the role of exogenously applied spermidine (Spm) in delaying both naturally and drought-induced senescence in the fourth youngest leaf of wheat, thereby helping it remain in a vegetative state for as long as possible. Wheat seedlings were grown until the emergence of the fourth youngest leaf (30 days after sowing, DAS) and then subjected to drought stress up to the 50th DAS. This leaf, which undergoes natural senescence due to aging, showed further signs of decline under drought conditions, including reductions in growth parameters, starch content, and the levels of CaІ⁺ and K⁺, along with increases in Na⁺ and soluble sugars content. Additionally, catalase isozyme expression varied significantly, while five distinct peroxidase isozymes were observed, depending on age and drought exposure. Concurrently, chloroplast ultrastructure exhibited notable alterations, such as reduced volume and a more spherical shape, diminished thylakoid membranes, increased diameter and number of plastoglobuli, disappearance of starch grains, stacking and bending of lamellae, thickening of the cell wall, and greater distance between chloroplasts and the cell wall. However, foliar application of Spm mitigated the adverse effects of senescence on growth parameters, carbohydrates, ion content, and isozyme expression of both catalase and peroxidase. It also improved chloroplast structure, as indicated by the chloroplasts’ restored elliptical shape, proximity to the cell wall, and reappearance of starch grains. These findings suggest that Spm can counteract the negative impacts of leaf senescence in wheat, significantly delaying the onset of senescence and helping the fourth leaf maintain its vegetative status. This delay could contribute to enhanced productivity by modulating key metabolites, ions, and chloroplast structure.

Chloroplast Ultrastructure, Drought, Ion Imbalance, Isozyme Expression, Leaf Senescence, Spermine, Wheat

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143185126

IDR: 143185126

Текст научной статьи Efficacy of spermine foliar application in delaying senescence of the fourth youngest leaf in wheat

Eventually, the fourth leaf in wheat undergoes senescence—a natural process of aging and degradation—as part of the plant’s overall developmental cycle. Leaf senescence can occur naturally or be accelerated by various environmental stressors. The onset of senescence in the fourth leaf refers to the beginning of a series of physiological and biochemical changes that lead to cellular deterioration and the remobilization of nutrients to other parts of the plant, particularly the developing grains. This process involves visible symptoms such as the loss of green pigmentation, a reduction in photosynthetic efficiency, membrane damage, accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), hydrolysis of macromolecules, disintegration of chloroplasts, and degradation of RNA, DNA, and proteins. It also includes the activation of senescence-associated genes, ion imbalance, and nutrient reallocation (Tripathi et al ., 2014).

Drought is a major abiotic stressor that accelerates leaf senescence, resulting in reduced photosynthesis and metabolic activity, ultimately diminishing crop productivity. Wheat, being the most important cereal crop globally, serves as a primary staple food. Therefore, improving wheat yield under drought stress is a critical objective to support global food security amidst a rapidly growing population. One potential strategy is to delay the senescence of the fourth leaf, preserving its youth and photosynthetic function for as long as possible. In response to drought stress, plants undergo various physiological modulations, including increases in soluble compounds such as sugars. These sugars play essential roles in enhancing cellular dehydration tolerance and protecting membrane integrity (Brito et al., 2019; Hassan et al., 2020; Trabelsi et al., 2024). Moreover, plant water status significantly influences the accumulation of ions such as Ca²⁺, K⁺, and Na⁺. Ca²⁺ supports physiological performance and stress adaptation, while K⁺ is vital for growth, maintaining cell turgor, and regulating stomatal function (Benlloch-González et al., 2010). nder drought conditions, increased Na⁺ accumulation is typically observed in senescing cells due to altered membrane permeability, disrupted ion homeostasis, and impaired Na⁺/K⁺ pump function, resulting in K⁺ deficiency (Larbi et al., 2020; Trabelsi et al., 2024).

Additionally, senescence is associated with oxidative stress, driven by imbalances in ROS production and detoxification. Trabelsi et al . (2024) noted that water deficits promote ROS accumulation, leading to lipid peroxidation and membrane damage. Antioxidant defense systems, including enzymatic antioxidants like catalase and peroxidase, play crucial roles in mitigating oxidative damage (Nandi et al ., 2019). ROS are predominantly generated in chloroplasts (Sobieszczuk-Nowicka and Legocka, 2014), and under stress, they cause structural damage such as disruption of chloroplast envelopes and increased numbers of plastoglobuli, along with thylakoid disorganization (Shu et al ., 2013; Domínguez and Cejudo, 2021; Hu et al ., 2023). Mulisch and Krupinska (2013) reported that during senescence, chloroplasts transform into gerontoplasts—changing from ellipsoidal to spherical shapes, reducing in volume, degrading thylakoid systems, and accumulating large plastoglobules. These detrimental effects may be mitigated by exogenous application of protective agents such as spermine (Spm), a polyamine (PA). PAs are small organic molecules found in both free and bound forms in all living organisms, with diverse roles in stabilizing membranes and macromolecules. They have been recognized as anti-senescence agents due to their ability to retard chlorophyll degradation and prevent membrane damage (Navakoudis et al ., 2007). Exogenous application of PAs enhances endogenous PA levels, which typically decline during senescence (Cao, 2010). Shu et al . (2013) reported that Spm alleviated stress-induced structural damage to the photosynthetic apparatus and reduced oxidative stress. Similarly, Serafini-Fracassini et al . (2010) demonstrated that Spm protected chloroplast complexes in senescing Lactuca leaves.

In wheat, the fourth youngest leaf plays a crucial role in tillering and overall plant development. It contributes significantly to photosynthesis and is also sensitive to environmental factors such as cold or drought. Given wheat’s global strategic importance, improving its resilience to stress is essential. One approach is the cultivation of wheat on neglected or marginal lands by enhancing drought tolerance through delaying senescence of the fourth leaf via application of compounds like Spm. This supports sustained nutrient supply and photosynthetic activity, which are key to maintaining productivity. Therefore, the objective of the present study is to characterize normal and drought-induced senescence in the fourth wheat leaf and to assess the potential of exogenous Spm application in delaying this process. Specifically, the study evaluates Spm's effects on mesophyll chloroplast ultrastructure, growth parameters, carbohydrate fractions, ion content (Ca²⁺, K⁺, and Na⁺), and the expression patterns of catalase and peroxidase isozymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and growth conditions

Certified grains of wheat ( Triticum aestivum L. cultivar Misr 2), obtained from Sakha Agricultural Research Station, Kafr El-Sheikh, Egypt, were surface sterilized in 1% w/v sodium hypochlorite for 10 min, rinsed with water several times then soaked in water for 12 h. Thereafter grains were sown in plastic pots (25 cm in diameter) each contained 2 kg of soil (clay:sand; 2:1 w/w), approximately 2 cm-depth, 8 seeds per pot, allowed to grow at 20±2/10±2°C, day/night temperature with a 11-h photoperiod at 400-450 mol m-2 s-1 PPFD and thereafter thinned to only four. On the 7th and the 14th DAS, seedlings were supplied with half strength Long Ashton nutrient solution. All pots were irrigated with tap water until developing the 4th youngest leaf (30 days after sowing, DAS) at which pots were divided into two groups; one was left as control (each pot was irrigated with 200 ml water twice a week) and the other group was subjected to drought stress by water withholding. On the 30th DAS, the pots of both groups (watered and drought) were divided into two subgroups; one was foliar sprayed once with water giving 2 treatments (control and drought) and the other group was sprayed once with 100 µM Spm containing 0.01% Tween-20 surfactant giving 2 treatments (control with Spm and drought with Spm); every pot received 30 ml water or Spm using a hand sprayer. The experiment (with the 4 types of treatments, 3 replications for each) was left up to the late stage of senescence (50th DAS)

during which the 4th youngest leaf was harvested randomly from each treatment on the 30th, 37th, 44th, 47th and the 50th DAS, washed thoroughly with distilled water and plotted dry between layers of tissue for determination of growth parameters and for the subsequent analyses. Fresh weight was determined and then oven-dried at 80 ºC for 2 days for dry weight determination from which water contents were calculated.

Determination of carbohydrate fractions

Soluble sugars were extracted from dry leaf tissue (0.5 g) with 80% ethanol (Schortemeyer et al ., 1997). For glucose determination, an aliquot of the extract (0.5 ml) was mixed with 2.5 ml of o-toluidine reagent (2 g of thiourea dissolved in 60 ml of o-toluidine then raised to 100 ml with glacial acetic acid) and left to react at 97 °C in water bath for 15 min. After cooling, the absorbance was measured at 625 nm (Webster et al ., 1971). Fructose was determined in an aliquot of the extract (0.5 ml) reacted with 0.5 ml of resorcinol reagent (0.1 g resorcinol and 0.25 g of theorem dissolved in 100 ml of glacial acetic acid) and 2 ml of 5 % HCl at 80°C in water bath for 10 min. After cooling, the absorbance was measured at 550 nm within 30 min (Devi, 2007). For sucrose determination, 0.1 ml of the ethanolic extract was digested by 0.1 ml of 5.4 N KOH in boiling water bath for 10 min. After cooling, 3 ml of freshly-prepared anthrone reagent (0.15 g of anthrone dissolved in 100 ml of 72 % H 2 SO 4 ) were added, incubated at 97 °C in water bath for about 8 min, cooled, and then absorbance was measured at 625 nm (Laurentin and Edwards, 2003). Determination of starch was performed in the residues remained after extraction of soluble sugars. The residues were suspended in 1.6 M perchloric acid at 70 °C in water bath for 2 h, cooled and centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 10 min and then the released soluble sugars were determined as glucose.

Determination of calcium, potassium and sodium ions

Ca2+, K+ and Na+ were extracted by the homogenization of about 0.5 g dry leaf tissue in ultra-high purity water then heated in water bath at 95 °C for 1h, cooled and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 20 min then ion contents were determined in the diluted supernatants

(Hansen and Munns, 1988) using Jenway PFP7 flame photometer.

SDS-PAGE electrophoretic analysis for catalase and peroxidase isozymes

Catalase was extracted with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM of EDTA followed by centrifugation at 12000 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C (Nurhidayah et al., 2014) while peroxidase was extracted with 0.2 M Tris -HCl buffer (pH 7.8) containing 14 mM β-mercaptoethanol then centrifuged at 10000 ×g for 20 min at 4 °C (El-Ichi et al. 2008). Total soluble proteins were separated on non-denaturating Poly Acrylamide Gels (PAG) without mercaptoethanol and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) using the Bio-Rad Mini Protean 3 equipment (Laemmli, 1970). The resolving gel contained 10 % acrylamide is composed of 0.4 ml acrylamide solution, 3.4 ml water, 2.5 ml gel buffer, 100 µl SDS solution, 50 µl ammonium persulphate, and 5 µl N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED). The stacking gel contained 5% acrylamide is composed of 1.7 ml acrylamide solution, 5.7 ml water, 2.5 ml gel buffer, 100 µl SDS solution, 50 µl ammonium persulphate, and 10 µl TEMED. Equal amounts of protein extracts were mixed with sample buffer and 10 µg were loaded and separated at 4 °C. To visualize catalase profile, gels were soaked in 3.27 mM H2O2 for 25 min, rinsed twice in distilled water, and stained in a freshly prepared solution containing 1% (w/v) of both potassium ferricyanide and ferric chloride (Anderson et al., 1995). Staining for peroxidase was achieved by soaking in distilled water then in a solution containing 25 mg benzidine dihydrochloride with two drops of glacial acetic acid and 50 ml of distilled water with five drops of 1% freshly prepared H2O2 added to the mixture immediately before use (Larsen and Benson, 1970). The gels were scanned and analyzed by the Total Lab 100. The electrophoresis buffer comprised 30.3 g Tris base, 144 g glycine and 10 g SDS dissolved in 1 L water and stored at 4 °C, whereas the stacking gel buffer was 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), but the resolving gel buffer was 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), and the sample buffer was 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) containing 10% glycerol and 5% mercaptoethanol. Acrylamide/bisacrylamide solution comprised 29.2 g acrylamide and 0.8 g bisacrylamide dissolved in 100 ml distilled water while both SDS and ammonium persulphate solutions were freshly prepared as 10% in distilled water. TEMED was obtained from Sigma chemical.

Ultra-structure of chloroplast using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

A fixative buffer solution comprising 0.2 M phosphate buffer (50 ml), 16% formaldehyde (20 ml) and 50% glutaraldehyde (10 ml) then diluted to 100 ml was used according to Morris (1965). Fixatives containing both formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde were used to give better tissue fixation than either of these aldehydes used separately. Formaldehyde penetrates tissue more rapidly than glutaraldehyde, but its fixation ability is less permanent. The use of this combination provides rapid stabilization of cell ultrastructure by formaldehyde, followed by a more permanent fixation by the subsequent treatment with the slower penetrating glutaraldehyde. Tissue blocks of approximately 1 mm3 were immersed in this fixative for 30 min to 2 h, wash with the appropriate buffer and then post fixed with 1% osmium tetraoxide (OsO 4) buffered with cacodylate for 2 h. ltrathin sections were observed at 80 KV using the JEOL JEM -2100 TEM at the EM nit, Alexandria niversity, Egypt.

Statistical Analysis

The experimental design was randomized block arrangement comprising 4 treatments (control, control+Spm, drought, and drought +Spm) in three replications for 5 intervals (30, 37, 44, 47 and 50 DAS). Microsoft Excel software and analysis of variance were used for statistical analysis. Means were compared using revised Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at 0.05 levels.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, the fresh and dry weights of the fourth youngest leaf of wheat cultivar Misr 2 increased gradually from 30 to 47 days after sowing (DAS), then declined at 50 DAS, corresponding to the late stage of senescence. Drought stress significantly reduced both fresh and dry weights compared to control plants. However, foliar application of spermine (Spm) markedly alleviated the impact of drought, particularly during the early stages. While water content in the fourth youngest leaf remained nearly constant in control plants throughout the growth period, drought caused a significant reduction. In contrast, Spm treatment improved water content under drought conditions, although values remained lower than those in well-watered controls.

Table 2 shows that glucose and sucrose contents in the fourth youngest leaf increased with age up to 47 DAS, followed by a decrease at 50 DAS. Drought stress led to a significant drop in both sugars, but Spm foliar spray mitigated this effect, restoring glucose and sucrose levels close to control values. Conversely, fructose content declined steadily in all treatments with age and showed a more pronounced decrease under drought. Spm application partially alleviated this decline. Similarly, starch content gradually decreased with age and further declined under drought stress. Spm treatment significantly improved starch content in both control and drought-stressed plants, with drought-stressed plants showing values near those of the control.

As shown in Table 3 , Ca² ⁺ , K ⁺ , and Na ⁺ contents increased from 30 to 44 DAS in well-watered plants, then declined sharply during senescence. Drought stress significantly reduced Ca² ⁺ and K ⁺ levels while increasing Na ⁺ accumulation. Spm foliar application mitigated these effects, restoring Ca² ⁺ and K ⁺ and reducing Na ⁺ accumulation to levels similar to those of the respective controls. As a result, the K ⁺ /Na ⁺ ratio, which was higher in control plants, declined under both natural and drought-induced senescence—more markedly under drought. Spm increased the K ⁺ /Na ⁺ ratio in both control and drought-treated plants. Changes in Ca² ⁺ were relatively minor during senescence, but drought-induced reductions were significantly reversed by Spm treatment.

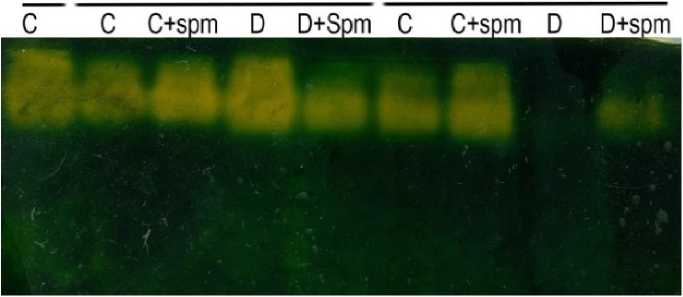

In Figure 1, catalase isozyme expression varied across treatments. In control plants, catalase was expressed until 47 DAS but disappeared entirely by 50 DAS. nder drought stress, isozyme intensity peaked at 37 DAS, then declined and disappeared by 44 DAS. Spm treatment enhanced catalase isozyme expression throughout 30–47 DAS under both control and drought conditions.

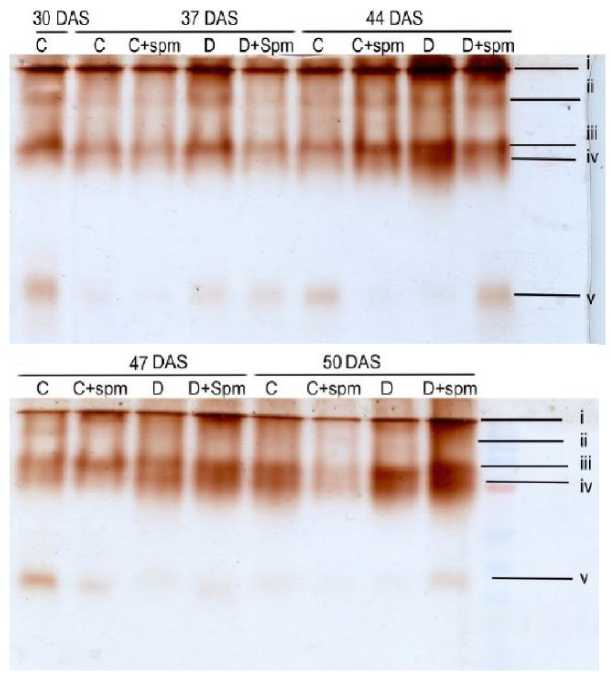

Regarding peroxidase, five distinct isozymes were observed, their expression patterns varying with senescence and drought stress (Figure 2) . Isozyme I was consistently present across all treatments and increased up to 47 DAS before declining. Drought enhanced its expression, which Spm modulated to slightly lower levels in drought-stressed plants and slightly higher levels in controls. Overall, isozyme expression was higher under drought, regardless of Spm treatment. However, all five isozymes were concurrently expressed only in control plants at 47 DAS. In other treatments, the number of detectable isozymes ranged from one to four ( Table 4 ). For instance, isozyme II was induced by drought at 37 and 44 DAS with or without Spm, and in controls at 44 DAS. Isozyme III was suppressed by Spm in controls at 30 DAS, while isozyme IV was induced from 44 DAS onward. Isozyme V disappeared at 37 DAS in both control and Spm-treated plants and from drought-stressed plants from 44 DAS onward.

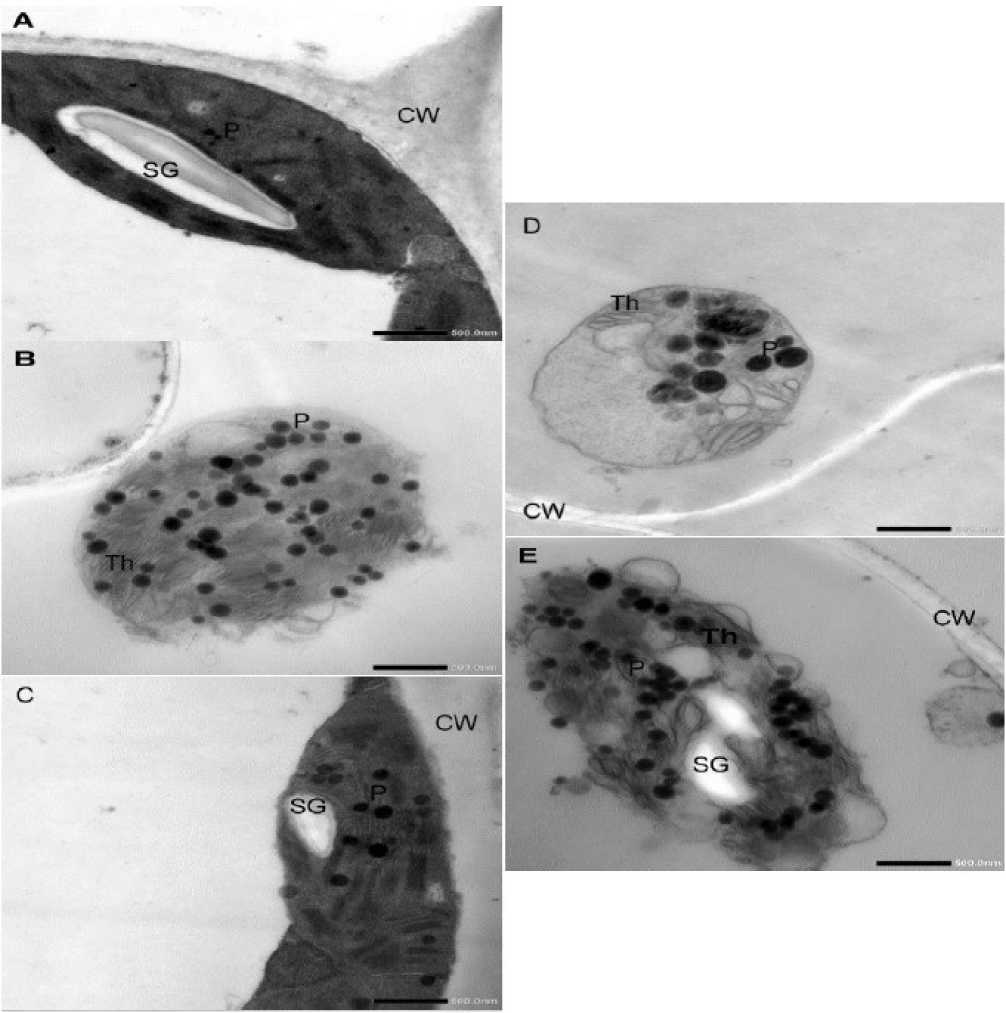

Chloroplast ultrastructure, observed via transmission electron microscopy (Figure 3), was examined at two time points: 30 DAS (prior to treatment) and 47 DAS (during senescence). At 30 DAS, chloroplasts were intact and oval-shaped, located close to the cell wall with compact thylakoid stacks, well-defined grana lamellae, few plastoglobuli, and prominent starch grains (Fig. 3A). By 47 DAS, senescing leaves exhibited smaller, spherical chloroplasts with reduced thylakoids, increased plastoglobuli, and absence of starch grains (Fig. 3B). Drought stress at 47 DAS further damaged chloroplasts: increasing cell wall thickness, separating chloroplasts from the cell wall, eliminating starch grains, increasing plastoglobuli diameter and number, and disorganizing the thylakoid structure with bending and stacking of lamellae. Spm foliar application improved chloroplast integrity in both control and drought-treated plants. In well-watered Spm-treated leaves, chloroplasts retained an oval shape, remained close to the cell wall, and showed well-organized grana, fewer plastoglobuli, and intact starch grains (Fig. 3C). In drought-stressed plants treated with Spm, chloroplasts were more elliptical and detached from the cell wall. Although thylakoid lamellae were swollen and partially disorganized, starch grains reappeared, and plastoglobuli number increased only moderately (Fig 3D).

Table 1. Changes of fresh weight, dry weight and water content of the fourth youngest leaf of 30-day old wheat cultivar Misr 2 subjected to drought stress without or with foliar spray of spermine (Spm) from the onset of senescence (30 days after sowing, DAS) up to late senescence (50 DAS). Values are means ± SD (n=6). Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

|

DAS |

30 |

37 |

44 |

47 |

50 |

|

Treatment |

Fresh weight (mg leaf-1) |

||||

|

Control |

380.3 ± 13.2 a |

378.9 ± 18.1 b |

416.1 ± 27.7 b |

455.5 ± 28.9 a |

204.8 ± 24.2 b |

|

Control+Spm |

373.8 ± 12.9 a |

490.4 ± 17.7 a |

443.5 ± 20.0 a |

472.9 ± 19.7 a |

280.0 ± 16.7 a |

|

Drought |

373.5 ± 12.9 a |

359.4 ± 12.4 b |

202.0 ± 16.5 d |

207.2 ± 17.6 c |

79.8 ± 13.4 d |

|

Drought+Spm |

373.9 ± 12.8 a |

362.6 ± 11.7 b |

320.9 ± 25.4 c |

393.2 ± 38.5 b |

126.9 ± 23.3 c |

|

Dry weight (mg leaf-1) |

|||||

|

Control |

65.7 ± 1.2 b |

65.8 ± 7.7 b |

75.3 ± 3.9 b |

92.3 ± 3.7 a |

37.7 ± 4.5 b |

|

Control+Spm |

70.7 ± 2.4 a |

87.9 ± 4.9 a |

78.2 ± 2.1 a |

95.9 ± 4.6 a |

53.3 ± 2.1 a |

|

Drought |

65.4 ± 1.9 b |

61.9 ± 1.5 b |

53.9 ± 1.8 c |

53.2 ± 1.6 c |

27.2 ± 1.3 d |

|

Drought+Spm |

69.3 ± 2.1 ab |

57.2 ± 1.9 b |

75.3 ± 2.3 b |

81.8 ± 3.2 b |

30.7 ± 2.1 c |

|

Water content (%) |

|||||

|

Control |

82.36 ± 1.9 a |

82.61 ± 1.1 a |

81.86 ± 2.8 b |

79.64 ± 2.9 a |

82.86 ± 2.7 a |

|

Control+Spm |

82.11 ± 1.7 a |

82.66 ± 1.5 a |

82.33 ± 1.8 a |

79.72 ± 1.5 a |

80.95 ± 1.3 a |

|

Drought |

82.16 ± 1.2 a |

83.15 ± 1.4 a |

74.37 ± 1.5 d |

74.46 ± 1.8 c |

67.93 ± 1.2 c |

|

Drought+Spm |

82.22 ± 1.4 a |

83.79 ± 1.5 a |

76.53 ± 1.6 c |

76.63 ± 1.2 b |

74.78 ± 1.4 b |

Table 2. Changes of Ca2+, K+, Na+ and K+/Na+ ratio of the fourth youngest leaf of 30-day old wheat cultivar Misr 2 subjected to drought stress without or with foliar spray of spermine (Spm) from the onset of senescence (30 days after sowing, DAS) up to late senescence (50 DAS). Values are means ± SD (n=6). Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

|

DAS |

30 |

37 |

44 |

47 |

50 |

|

Treatment |

Ca2+ content (µmole g-1 dry weight) |

||||

|

Control |

92.2 ± 8.9 a |

96.6 ± 9.8 b |

115.3 ± 8.4 ab |

119.5 ± 8.1 ab |

110.9 ± 9.3 b |

|

Control+Spm |

92.2 ± 8.9 a |

115.9 ± 7.7 a |

132.6 ± 9.7 a |

140.3 ± 9.4 a |

140.0 ± 9.7 a |

|

Drought |

92.2 ± 8.9 a |

79.9 ± 9.7 c |

75.6 ± 11.4 c |

69.4 ± 7.7 c |

61.2 ± 10.5 d |

|

Drought+Spm |

92.2 ± 8.8 a |

95.5 ± 11.1 b |

95.5 ± 7.8 b |

106.5 ± 9.6 b |

84.5 ± 7.3 c |

|

K+ content (µmole g-1 dry weight) |

|||||

|

Control |

479.2 ± 38 a |

595.1 ± 44 ab |

513.7 ± 31 b |

458.8 ± 35 b |

411.4 ± 44 a |

|

Control+Spm |

479.2 ± 38 a |

636.8 ± 34 a |

644.7 ± 41 a |

649.3 ± 46 a |

413.3 ± 40 a |

|

Drought |

479.2 ± 38 a |

384.9 ± 23 c |

281.6 ± 43 d |

249.4 ± 39 d |

225.6 ± 27 c |

|

Drought+Spm |

479.2 ± 38 a |

516.9 ± 32 b |

466.1 ± 38 c |

422.6 ± 41 c |

374.5 ± 36 b |

|

Na+ content (µmole g-1 dry weight) |

|||||

|

Control |

11.91 ± 1.44 a |

13.83 ± 1.59 c |

14.35 ± 1.66 c |

17.17 ± 1.97 c |

18.11 ± 1.91 c |

|

Control+Spm |

11.91 ± 1.44 a |

12.55 ± 1.66 c |

13.67 ± 1.23 c |

16.07 ± 1.48 c |

18.21 ± 1.72 c |

|

Drought |

11.91 ± 1.44 a |

32.05 ± 2.53 a |

42.62 ± 3.57 a |

47.24 ± 4.13 a |

48.91 ± 4.26 a |

|

Drought+Spm |

11.91 ± 1.44 a |

22.89 ± 2.15 b |

26.00 ± 3.01 b |

29.40 ± 3.11 b |

30.26 ± 4.03 b |

|

K+/Na+ ratio |

|||||

|

Control |

40.25 ± 2.8 a |

43.02 ± 2.4 b |

35.80 ± 2.7 b |

26.49 ± 2.1 b |

22.72 ± 2.1 a |

|

Control+Spm |

40.25 ± 2.8 a |

50.76 ± 3.5 a |

47.16 ± 3.8 a |

40.40 ± 3.4 a |

22.69 ± 1.9 a |

|

Drought |

40.25 ± 2.8 a |

12.01 ± 2.1 d |

6.61 ± 1.1 d |

5.28 ± 0.8 d |

4.61 ± 0.7 c |

|

Drought+Spm |

40.25 ± 2.8 a |

22.59 ± 2.3 c |

17.92 ± 2.1 c |

14.37 ± 1.3 c |

12.38 ± 1.4 b |

Table 3. Changes of carbohydrate fractions (glucose, fructose, sucrose and starch) of the fourth youngest leaf of 30-day old wheat cultivar Misr 2 subjected to drought stress without or with foliar spray of spermine (Spm) from the onset of senescence (30 days after sowing, DAS) up to late senescence (50 DAS). Values are means ± SD (n=6). Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

|

DAS |

30 |

37 |

44 |

47 |

50 |

|

Treatment |

Glucose content (mg g-1 dry weight) |

||||

|

Control |

1.91 ± 0.21 a |

2.61 ± 0.31 b |

2.63 ± 0.22 b |

3.61 ± 0.23 a |

2.88 ± 0.18 a |

|

Control+Spm |

1.91 ± 0.21 a |

2.83 ± 0.27 a |

2.78 ± 0.21 a |

3.38 ± 0.24 a |

2.76 ± 0.19 a |

|

Drought |

1.91 ± 0.21 a |

2.24 ± 0.21 c |

2.18 ± 0.31 c |

2.31 ± 0.21 b |

2.25 ± 0.22 b |

|

Drought+Spm |

1.91 ± 0.21 a |

2.85 ± 0.15 a |

2.27 ± 0.18 c |

2.22 ± 0.19 b |

2.74 ± 0.23 a |

|

Fructose content (mg g-1 dry weight) |

|||||

|

Control |

67.98 ± 5.45 a |

62.13 ± 4.38 b |

49.13 ± 3.79 b |

54.22 ± 6.04 b |

38.82 ± 4.18 bc |

|

Control+Spm |

67.98 ± 5.45 a |

63.56 ± 4.11 b |

63.55 ± 5.87 a |

78.77 ± 8.11 a |

51.20 ± 5.45 a |

|

Drought |

67.98 ± 5.45 a |

62.42 ± 5.37 b |

39.49 ± 3.68 c |

42.46 ± 3.81 c |

36.64 ± 3.11 c |

|

Drought+Spm |

67.98 ± 5.45 a |

74.44 ± 6.15 a |

67.73 ± 5.55 a |

60.51 ± 5.43 b |

41.14 ± 3.59 b |

|

Sucrose content (mg g-1 dry weight) |

|||||

|

Control |

34.49 ± 2.23 a |

58.76 ± 4.38 a |

68.02 ± 3.58 b |

121.14 ± 6.97 a |

65.23 ± 4.12 b |

|

Control+Spm |

34.49 ± 2.23 a |

50.21 ± 4.22 b |

68.28 ± 5.13 b |

130.78 ± 8.46 a |

81.08 ± 6.15 a |

|

Drought |

34.49 ± 2.23 a |

56.91 ± 0.21 a |

61.41 ± 0.31 c |

41.42 ± 0.21 c |

14.58 ± 0.22 d |

|

Drought+Spm |

34.49 ± 2.23 a |

50.95 ± 0.15 b |

77.36 ± 0.18 a |

90.62 ± 0.19 b |

41.06 ± 0.23 c |

|

Starch content (mg g-1 dry weight) |

|||||

|

Control |

18.99 ± 1.73 a |

21.02 ± 1.87 b |

55.04 ± 3.97 b |

119.03 ± 9.12 b |

68.75 ± 5.74 b |

|

Control+Spm |

18.99 ± 1.73 a |

24.36 ± 2.37 b |

61.34 ± 5.57 a |

151.63 ± 9.57 a |

143.80 ± 9.18 a |

|

Drought |

18.99 ± 1.73 a |

40.02 ± 3.65 a |

44.19 ± 3.92 c |

25.79 ± 2.88 d |

20.43 ± 1.85 d |

|

Drought+Spm |

18.99 ± 1.73 a |

21.84 ± 1.88 b |

54.95 ± 4.78 b |

47.02 ± 5.01 c |

31.57 ± 3.33 c |

30 DAS 37 DAS 44 DAS

47 DAS 50 DAS

C C+som D D+Som C C+spm D D+som

Figure 1: Electrophoretic analysis of catalase of fourth youngest leaf of 30-day old wheat cultivar Misr 2 subjected to drought stress without or with foliar spray of spermine (Spm) from the onset of senescence (30 days after sowing, DAS) up to late senescence (50 DAS).

Table 4. The presence (+) or absence (-) of the five electrophoretic analysis of peroxidase isozymes of the fourth youngest leaf of 30-day old wheat cultivar Misr 2 subjected to drought stress without or with foliar spray of spermine (Spm) from the onset of senescence (30 days after sowing, DAS) up to late senescence (50 DAS).

|

DAS |

Treatment |

Peroxidase isozymes |

||||

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

||

|

30 |

Control |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

Control+Spm |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

Drought |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

Drought+Spm |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

37 |

Control |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

|

Control+Spm |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

Drought |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

|

|

Drought+Spm |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

|

|

44 |

Control |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

Control+Spm |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

Drought |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

Drought+Spm |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

47 |

Control |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

|

Control+Spm |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

|

Drought |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

|

Drought+Spm |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

50 |

Control |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

Control+Spm |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Drought |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

|

Drought+Spm |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Figure 2: Electrophoretic analysis of peroxidase of fourth youngest leaf of 30-day old wheat cultivar Misr 2 subjected to drought stress without or with foliar spray of spermine (Spm) from the onset of senescence (30 days after sowing, DAS) up to late senescence (50 DAS).

Figure 3: Transmission electron micrograph showing chloroplast ultra-structure of fourth youngest leaf of 30-day old wheat cultivar Misr 2 subjected to drought stress without or with foliar spray of spermine (Spm) from the onset of senescence (30 days after sowing, DAS). A, at the onset of senescence (30 DAS, prior to treatment); B, control plants with normal irrigation without Spm at 47 DAS (during senescence); C, control plants with normal irrigation with Spm at 47 DAS (during senescence); D, drought-stressed plants without Spm at 47 DAS (during senescence); E, drought-stressed plants without Spm at 47 DAS (during senescence),

DISCUSSION

Plant leaves possess mechanisms that influence their fate during aging or under stress conditions, undergoing sequential physiological and biochemical changes that lead to senescence and programmed cell death. Leaf senescence can limit yield in certain crops;

therefore, delaying its onset may enhance biomass accumulation and potentially increase crop yield. In the present study, increasing leaf age or exposure to drought stress significantly reduced fresh weight, dry weight, and water content in the fourth leaves of wheat plants. However, foliar application of spermine (Spm) ameliorated these parameters in well-watered plants and mitigated the adverse effects of drought in stressed plants. These improvements suggest that Spm delays both natural and drought-induced leaf senescence.

Growth inhibition under drought stress is likely due to a reduction in plant water content. Shaddad et al . (2013) attributed this inhibitory effect to decreased water potential of the cell sap, the osmotic effects of water stress, or inhibition of cell division. The effectiveness of Spm foliar application in alleviating the effects of natural and drought-induced senescence was evident and aligns with the findings of Mustafavi et al . (2016), who reported that Spm improved growth characteristics in Valeriana officinalis under drought stress. Spm belongs to the class of polyamines (PAs)—low molecular weight aliphatic nitrogenous bases containing two or more amino groups. These compounds are produced during metabolism and are found in nearly all cells. Due to their essential roles in plant growth, development, and stress responses, PAs are considered novel plant biostimulants (Chen et al ., 2019).

In addition to promoting growth, PAs regulate soluble compounds and ion balances in senescing leaves. In this study, Spm increased soluble sugar levels and promoted starch accumulation. These results are consistent with Chen et al . (2019), who suggested that soluble sugars may accumulate during senescence despite reduced photosynthetic activity, possibly due to starch-to-hexose conversion, excess carbon availability, reduced amino acid synthesis, or decreased sugar export. Growth arrest under drought may be a mechanism for preserving carbohydrates to sustain metabolism and ensure prolonged energy supply. The regulation of sugar content by Spm may stem from its role in preserving the structure and function of the photosynthetic apparatus.

nder stress, plants activate endogenous mechanisms to cope with adverse conditions. Soluble sugars, as osmotically active organic compounds, help balance vacuolar solute potential, support metabolism, regulate development, and initiate senescence programs (Yoshida, 2003). Environmental stress also alters the concentration of key elements such as Ca²⁺, K⁺, and Na⁺. nder natural and drought-induced senescence, Ca²⁺ and K⁺ levels decreased while Na⁺ increased, leading to a decline in the K⁺/Na⁺ ratio. Spm application counteracted these imbalances, increasing Ca²⁺ and K⁺ contents and thereby enhancing growth. Ca²⁺ is crucial for maintaining membrane and cell wall integrity, ion transport, and enzyme activity (Hadi and Karimi, 2012), while K⁺ plays a vital role in osmotic regulation, cell turgor, and drought tolerance (Wei et al., 2013). In contrast, high Na⁺ concentrations are toxic to most plants and disrupt physiological processes. Benlloch-González et al. (2010) reported that K⁺ deficiency reduced leaf water potential and photosynthesis in sunflower and increased drought sensitivity. Similarly, Wang et al. (2007) found that in salt-treated cucumber seedlings, K⁺ and the K⁺/Na⁺ ratio decreased, but exogenous PAs reduced Na⁺ accumulation and increased K⁺ levels and the K⁺/Na⁺ ratio. Ali (2000) also demonstrated that PAs reduced Na⁺ accumulation in Atropa belladonna exposed to salinity.

Leaf senescence also affected isozyme expression of catalase and peroxidase, key antioxidant enzymes that detoxify reactive oxygen species (ROS). While only one catalase isozyme was detected, five peroxidase isozymes were observed, varying with age and drought conditions. Spm treatment alleviated these changes and enhanced isozyme expression, suggesting improved oxidative stress defense. This is consistent with Radhakrishnan and Lee (2013), who reported increased peroxidase activity in Spm-treated soybean, and Sun et al . (2019), who observed enhanced catalase and peroxidase activities in Spm-treated zoysiagrass. Puyang et al . (2015) also noted that PAs prevent oxidative damage under flooding stress. By increasing antioxidant enzyme activity, Spm likely reduces ROS accumulation, protecting leaf cells from damage and delaying senescence.

Maintaining chloroplast structural integrity is essential for photosynthesis. Transmission electron micrographs of the fourth leaves revealed senescence-related chloroplast degradation. Normal chloroplasts exhibited oval shapes and tightly stacked thylakoids. However, with age or drought, plastoglobuli number and size increased, starch grains disappeared, and thylakoid stacks loosened. These changes are consistent with

Sobieszczuk-Nowicka and Legocka (2014), who noted early senescence symptoms in chloroplasts, and Prochazkova and Wilhelmova (2007), who observed plastoglobuli accumulation and thylakoid disorganization in gerontoplasts. Such structural alterations under stress compromise photochemical efficiency and damage the D1 protein of PSII due to ROS production in chloroplasts. Salinity stress similarly affects chloroplast structure, causing envelope damage and increased plastoglobuli (Shu et al ., 2013). Foliar Spm application preserved chloroplast integrity, reduced plastoglobuli numbers, and maintained starch grain presence, indicating protection of the photosynthetic system. Shu et al . (2013) also reported that Spm protected Lactuca leaves from chloroplast degradation by regulating antioxidant systems and improving PSII efficiency.

CONCLUSIONS

Aging and drought stress induced senescence in the fourth leaves of wheat, leading to reductions in growth parameters, carbohydrate levels, and essential ions (Ca² ⁺ and K ⁺ ), along with increases in Na ⁺ and ROS. Senescence also resulted in chloroplast malformations — decreased size, altered shape, thylakoid disorganization, loss of starch grains, increased plastoglobuli, and thickened cell walls. Spm application mitigated these detrimental effects, restoring growth and biochemical markers to near-control levels. Chloroplasts in Spm-treated plants were elliptical, retained starch grains, and showed moderate plastoglobuli numbers, despite some thylakoid disorganization. These findings suggest that Spm delays wheat leaf senescence by modulating metabolites, ion content, and chloroplast structure.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.