Enhanced dynamic programming-based method for text line recognition in documents

Автор: Chernyshova Y.S., Suloev K.K., Shehskus A.V., Arlazarov V.V.

Журнал: Компьютерная оптика @computer-optics

Рубрика: International conference on machine vision

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.49, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

On-premise text recognition is in demand. Customers want to recognize bank cards to pay online, passports to fill in tickets' information and many more using their smartphones. As main approach to text recognition in the last two decades is artificial neural networks the resulting solutions tend to be resource-hungry and not fitting on mobile devices. In our paper, we introduce an enhanced method based on dynamic programming and a fully convolutional network for text line recognition that allows this classic model to demonstrate competitive results with much heavier architectures. The main idea is the addition of the special pin into the network alphabet that allows to apply dynamic programming to analyze the raw neural network output effectively. As our main focus is the recognition of identity documents we employ public dataset MIDV-500 and its extension MIDV-2019 as a test sample. We compare our resulting recognizer with several published models, including TrOCR, Paddle OCR, and Tesseract OCR 5, to demonstrate its superiority in accuracy and performance trade-off. Our method is about 200 times faster than TrOCR, and in the most cases is about 2 times faster than Paddle OCR. The accuracy of our recognizer is comparable with Paddle OCR on MIDV-500 and is better on MIDV-2019, including it being about 2 times more accurate for machine-readable zones images.

Data synthesis, fully convolutional neural networks, ID documents recognition, OCR, on-device recognition, text line recognition

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140313270

IDR: 140313270 | DOI: 10.18287/COJ1761

Текст научной статьи Enhanced dynamic programming-based method for text line recognition in documents

Mobile applications with recognition modules become a part of everyday life. QR code payments replace bank cards in transport and shops [1, 2], bank cards recognition simplifies online shopping, and ID document recognition allows filling various forms with fewer typos. Also the KYC (Know Your Customer) introduction leads to the demands to increase recognition systems accuracy and performance [3]. In pursuit of the latest recognition models many applications provide so called "cloud" recognition that works in a following way: after the user takes a photo (or video) of the object to be recognized, the photo is transferred to the server, where the recognition system is up. After the recognition the results are passed back to the device. For example, Microsoft provides Azure AI Document Intelligence [4] to recognize various documents, including ID documents. The main reason of the popularity of "cloud" systems is that modern recognition systems contain artificial neural networks, and modern state-of-the-art architectures tend to be huge and not adapted for mobile processors. While this approach is acceptable for recognition of non-sensitive information in places with stable and fast internet connection, it is impermissible for many other situations, as it leads to the risk of the personal data leakage for the client and to the risk of violating personal data protection laws [5, 6] and leakage of confidential information for the company. Also, it can sufficiently worsen user experience if the internet connection is unstable or just slow. Moreover, this inconvenience increases with the size of the photo to be transferred, e.g. the necessary resolution of image for QR code recognition is typically lower than that for passport recognition. As a result, applications with embedded or "on-device" recognition systems appear. Such applications run recognition systems on premises and transfer only the final results as if the user entered data manually. To be useful in real life, "on device" recognition systems should provide accurate and fast recognition, which tends to narrow the scope of ANN-based algorithms. Moreover, many ID documents recognition systems include recognition modules for a variety of languages and writing systems in order to recognize the documents from all over the world. This fact enhance the memory restrictions for the employed models. We will look at these restrictions in more detail in Related works.

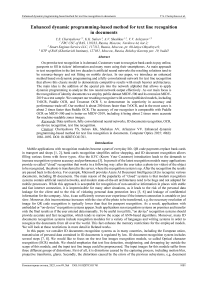

In this paper, we consider ID documents recognition systems as in many countries, including the European union, transmission of personal data contained in ID documents is regulated by law. ID document recognition system includes several steps [7, 8]. We would like to focus on the text line images recognition module, so called Optical character recognition (OCR) module. We should emphasize that text line detection, straightening, and dewarping lay outside the scope of this module, and the input text line image could be preprocessed. The input images for this module suffer from three different groups of distortions. First of all, it is distortions caused by the capturing process, including motion blur, projective transforms, glares. Secondly, the distortions caused by the errors of the previous subsystems, e.g. document localization, and fields extraction subsystems. Finally, ID documents have distinctive physical traits, such as lamination which increases the risk of highlights, and complex background with geometrical patterns and even background text. Also, the regular usage of these documents leads to text erasing, and fold marks [9]. Thus, the OCR module should be robust to all these distortions. Fig. 1 shows the examples of text line images taken from public datasets MIDV-500 [10] and MIDV-2019 [11]. It should be mentioned that for business documents (e.g. invoices) approaches that employ the preliminary recognition of all text and then use LLMs to get the properties (e.g. bank account, client's name, etc) grow in popularity [12], but they are outside the scope of this paper.

Fig. 1. Samples of text line images from ID documents from MIDV datasets

All in all, for the effective "on device" text line recognition we need a method that is simultaneously robust to the possible distortions and time- and memory-effective. As it has already been mentioned, ANNs are a modern to-go approach to OCR and our study is no exception. In this paper, we present an efficient fully convolutional network (FCN) and dynamic programming (DP) – based approach to the recognition of text line images suitable for the "on device" applications, and also show that to get high accuracy one should pay attention not only to the architecture of the ANN, but to the training strategy.

Related works

OCR module is an essential part of any document and text recognition system. Early systems contained OCR methods with explicit text line segmentation, i.e. with explicit division of one text line image into images of separate characters. Methods with explicit segmentation divide into two groups: method based on connected components analysis and methods based on projection analysis. In projection-based approaches, heuristic over-segmentation is of particular interest. In this approach, a segmenter tends to create more character candidates than necessary, including "garbage" images, i.e. oversegmented (parts of characters) and under-segmented (glued characters) ones. Then, in the basic approach a graph is built based only on the segmenter's scores. In a more complex variant, a classifier can recognize not only the normal characters, but also the previously mentioned "garbage". Thus, all character candidates are classified, and a graph is built based on the segmenter's and classifier's scores. The final part of the algorithm is the search of the best path in the graph. Heuristic over-segmentation has been used in many papers, including the famous paper by LeCun et al [13], but the segmenter used was always an image processing algorithm. Then, in 2020 the authors of 2CNN approach [14] proposed to use a FCN as a segmenter. Employment of the FCN allowed the authors to create a method robust to the distortions typical for camera-captured images. Moreover, 2CNN is a method intended to work "on device" and, thus, employs tiny ANNs. The authors of [15, 16] proposed to use a FCN for handwritten text recognition, but, in fact, their method includes a CNN with a fully-connected layer that detects the number of characters in the image. Also, in these approaches the authors add a "blank" character between the real characters to enhance the alignment.

At the same time, more and more end-to-end approaches to text line recognition appear. The one popular for many years is recurrent neural networks (RNN) that are used for scene text recognition [17, 18], historical documents recognition [19], camera-captured and scanned documents recognition [20, 30], and ID cards recognition [21]. Tesseract OCR which is well-known and widely used open-source OCR engine [14, 22, 23] also employs RNN, specifically long short term memory (LSTM) networks. Speaking about Tesseract OCR, we would like to emphasize that while the first version that appeared almost twenty years ago is outdated, modern versions of Tesseract OCR, starting from 4.0.0 (the current one is 5.3.2), use modern LSTM and show competitive recognition accuracy. The other ANN type that is gaining popularity and show state-of-the-art results is transformer [24]. Many studies focus on using transformers for OCR tasks [25, 26]. A popular open source OCR library Paddle OCR uses a tiny transformer in its third version [27]. At AAAI 2023 M. Li et al [28] presented a model entitled TrOCR that demostrated state-of-the-art results for several datasets including SROIE dataset [29] from one of the ICDAR 2019 challenges. In 2024 DTrOCR model [31] demonstrated even better results.

Therefore, all modern approaches to OCR employ ANNs. Moreover, in many cases ANNs present the main or even the only part of the algorithm. As a result, the need to use the OCR module on-the-premises rises the problem of an efficient usage of ANNs on the mobile devices that leads to some interesting results [32, 33, 34, 35]. Let us start with some numbers. The current top smartphones, e.g. iPhone 15 Pro Max or Samsung Galaxy S23+, have 8 GB RAM. According to statistics iPhone 11 that has 4 GB RAM is a rather popular smartphone. Moreover, many people use models like iPhone 7 Plus that has 3 GB RAM and Samsung Galaxy A03 Core that has 2 GB RAM. This numbers are important, as, for example, for TrOCR [28] the base model contains 334M parameters and takes up 1.33 GB. What is more, any application working with OCR should be multilingual and multi-script, i.e. be able to recognize a variety of writing systems (Arabic, Chinese, Indic languages), thus using several ANNs. The 2CNN approach [14] is suitable for mainstream mobile devices, but the separate segmentation and classification steps, firstly, make the system's updates more difficult as two CNNs are usually fine-tuned to each other, and, secondly, the end-to-end solutions are more context-aware, e.g., in the methods with explicit segmentation classifier extracts information only from the segmented character, but in the end-to-end pipeline the ANN can include features of neighbour characters into the final decision. Tab. 1 provides a short overview of the discussed published approaches. Thus, we face a necessity for a 1CNN-based approach to text line images recognition with a tiny model.

Tab. 1. Overview of the previously published approaches to text line recognition

|

Approach/ system title |

Underlying model |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

TrOCR[28] |

Visual transformer |

High accuracy for a variety of input images |

Very large models that cannot be used on-device because of hardware restrictions, e.g. available RAM, and speed |

|

DTrOCR[28] |

Modified decoder part of TrOCR |

High accuracy for a variety of input images |

Very large models that cannot be used on-device because of hardware restrictions, e.g. available RAM, and speed |

|

CNN method[14] |

FCN for segmentation + CNN for recognition of separate characters |

High accuracy for text line images + highly efficient for mobile devices |

Two models demand fine-tuning to each other |

|

Paddle OCR v3[27] |

Attention-based model |

Efficient for separate languages |

Needs separate model for each language with similar alphabets |

|

Tesseract OCR 4 and higher |

LSTM |

Good recognition of dictionarybased texts, e.g. names |

Fails on texts with atypical models |

|

FineReader 15 |

Private RNN |

Popular library with closed code, has client support |

Expects high-quality images |

We proceed from the following considerations. Firstly, a 2CNN approach is successfully optimized for mobile devices and it employs a FCN that predicts cuts between the characters and a CNN classifies the segmented images. Secondly, method [15, 16] uses a CNN to predict the number of characters and a FCN with "blank" characters to recognize resulting image, but they scale the FCN input according to the predicted number of characters. Finally, the authors of CRAFT text detector [36], while not working with OCR, trained their model to show the score of the character center being in the given point and the score of the point being the center of a gap between two neighbouring characters. Thus, we realized that a FCN gives a perfect opportunity to recognize text line images if given additional information about mid-character gaps via a special synthetic pin but usually the researchers tend to add extra steps to avoid analyzing of the FCN output. In our paper, we present a data-driven approach to training a tiny FCN suitable for the recognition of text line images in ID documents.

Proposed approach

Basing on previously mentioned research we propose to use a FCN to recognize a text line image of arbitrary length to get a projection of the text line image on the horizontal axis. We should emphasize that our "projection" is not strictly consistent with its mathematical definition. It is a raw output of the FCN with size W± X 1 X A, where A is the size of the alphabet, for an input image I with size W X H ft xed X 1. After applying the FCN, we adapt the projection's size to W X 1 X A to get direct correspondence between the columns of the image and the projection. Each 1 X 1 X A subvector of the result contains scores of each alternative after the SoftMax, i.e. the sum of the elements of the subvector equals to 1. Finally, we use dynamic programming to find the best path. The algorithm has the following steps:

-

1. Scale input image to the predefined height (it is necessary to get the final projection with height equal to 1. The width stays arbitrary).

-

2. Apply the FCN to the scaled image to build projection P(x).

-

3. Employ dynamic programming to build the resulting path optimizing the sum of scores of characters' recognition, using predefined restrictions on character's width w £ [wm i n, wmax ].

-

4. Filter extra characters, e.g. multiple spaces on the borders of the image.

Additional synthetic pin to boost the dynamic programming

As we have mentioned, FCNs can recognize gaps between characters, for example, as "blanks". In this case, we speak about meaningless gaps between the characters, not about the "space" characters that should be a part of the recognition result. We propose to increase their importance in the algorithm and to use them as a special "synthetic pin", i.e. to allow them to explicitly participate in the best path optimization. For example, let us consider a FCN that recognizes English letters and spaces. In this case, the size of the alphabet A = 27 for basic implementation and A = 28 for an implementation with a synthetic pin. There is no difference in the architectures.

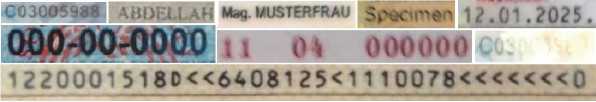

After we get the projection P(x) that contains scores for the classes including the synthetic pin, we need an efficient way to analyze the projection and to build resulting textual value. If you look at the projection in Fig. 2 (2) you would understand that just adding confident recognition of the synthetic pin to projection in the same way as for the other pins increase the number of local maxima that are not distinguishable from each other. As a result, building of the best recognition path would be even more difficult. Thus, we decide that we should process them in a different way. The basic scheme of the best path selection in P(x) is maximizing the score of the accumulated answer. As the synthetic pin marks gap between two consequent characters, i.e. the point in P (x) that should not be taken into the final answer, we decided that the best way to think about it as of a pin with negatively growing score. Fig. 3 demonstrates a short text line and its score, where the score is in the range [-1,1] with —1 marking the confident recognition of the synthetic pin. The same thing is shown in the step (2) in Fig. 2b, the right branch. We do it in the simple way. If the most confident pin for the current column is a gap we multiply the score by —1. As a result, the score diagram starts to have clear local maxima and minima. The addition of negative values in the places of gaps between the characters allows us to use dynamic programming more efficiently to optimize the best path successfully.

Fig. 2. the left branch, shows the result of the basic implementation of such a approach and the result is not so good. The recognizer tends to find spaces between neighbour characters and to divide wide characters into several ones. On the step (2) we show the top score for each column of the image. The red line denotes zero score. The base version of the approach (Fig. 2, the left branch) shows only positive score

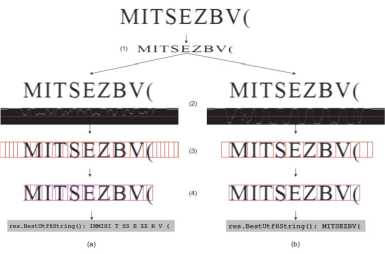

Fig. 3. FCN results and pipeline. Left – combined FCN result, center – recognition pipeline, right – per-alternative projections

To find the best path we need to maximize the following function:

(Si=i (ci - c lt - cl r )) x f ( N) ^ ты

where N denotes the length of the resulting string, c ^ is the score of the ith characters, c^ and C [r are the scores of synthetic pin to the left and to right of the ith character. We select every possible N and sets of C [ , c^ , C [r basing on w £ [Wmin, wmax ] and image width W.

f(N) (Eq. 2) is a special weight function to balance the selection of long and short strings. The input images of the same width can contain string of arbitrary length, e.g. it can be a string of one character with large spaces or the characters can take all the image. We cannot use the average score as in the long string it is more probable to select less confident character. For example, in Fig. 3 (left) the first character has smaller score than the other ones. If we used an average, we could loose this character and get "APPY" in the result.

f (N) = - ln(l + c^r/^) (2) N ln(l+l/N)

where ctr £ [0; 1] is a constant that means a threshold of the scores. If the scores of the next selected character is more than ctr the resulting optimized function value will increase, if it is smaller ctr the resulting optimized function value will decrease.

Recognition process without and with a synthetic pin. Left branch (branch a) shows the recognition process without a synthetic pin. Right branch (branch b) shows the same steps of the recognition process, but with a synthetic pin involved.

To employ dynamic programming to build the best path we, firstly, calculate the maximal possible number of the characters in the resulting string kmax according to image width W and characters' width range [wmin, wmax] (Eq. 3):

Is = max

W+Wmin-1 wmin

Then using the characters' width range [wmin, wmax] we set starting scores for columns of the image that could contain the beginning of the first character of the string (Eq. 4), i.e. the columns belonging to the range [0, wmax ]. We would like to emphasize that due to the restrictions on the width of the characters we do not have to calculate the whole W x kmax matrix. To calculate the paths, we employ Eq. 5, 6 and 7.

dp(x,0) = P(x) (4)

acur (x, k) = 0.5 x (PN(x — w/2) + PN (x + w/2)) (5) dp cur (x, k) = a cur (x, k) + P (x) (6) dp(x, k) = dp(xst, 0) + dp(xpr, k — 1) + dpcur (x, k) (7)

where xst denotes the starting point of dynamic, xpr is the column of previous best dynamic score in the current path, k is the index of the current character, w is the current width of the character, PN is the part of P with the negative synthetic scores.

Fig. 3 (center) shows the recognition pipeline with examples. The step of image preparation has not been discussed before, as, in fact, the algorithm itself does not demand any special modifications of the input image, but horizontal paddings tend to enhance the recognition results as it is better if meaningful local minima and maxima in P(x) and PN (x) are not right next to the image borders.

Also, it is important to mention that in the previous examples of the projection we have shown the best scores in one combined image. But, in fact, all scores of all alternatives are available. Fig. 3 (right) demonstrates per-class scores for a cropped alphabet for the sample image (we cropped the alphabet to the synthetic pin, space, and letters from the image for demonstrative purposes), the alternatives are sorted in the alphabetic order with synthetic pin being the last one.

Number of synthetic pin instances

When we add a synthetic pin into our model we should decide how to add it into our training data. The most obvious variant is to add synthetic pin wherever possible in the training samples, but in this case our sample will be very unbalanced as, for example, a text line containing N characters contains N — 1 synthetic pin instances. Thus, we decided that we should balance the probability of using the synthetic pin instance. We consider the following facts. If we create a uniformly distributed training sample we can calculate the probability of each character as 1/A. But the synthetic pin represents a gap between neighbouring characters. And if we consider the gap between the "AB" pair and the gap between the "AS" pair we notice that the gap's vicinity looks differently because of the different form of neighbouring characters. As a result, we can acquire A2 of differently looking gaps. Thus, we assume that the probability of taking the gap instance into the training sample should be higher than 1/A and we decide that as the number of different characters is A1, the probability of character synthesis is A-1, and the number of different gaps is A2, the probability of gap synthesis should be A-1/2.

Learning details

The crucial part of our learning process is usage of purely synthetic data. In fact, acquiring of natural data annotations for the proposed method is time- and resources-consuming. Moreover, it demands very painstaking manual labour to provide exact coordinates for the millions of characters in text line images. We describe our datasets in more detail in Datasets section. Fig.4 demonstrates the geometrical annotations necessary for the FCN training: the x-abscissas of the left and borders of each character, the cuts between them and also the vertical boundaries of the text line image.

|E|n|i|g|x|f|d|k|(| ^

I I О I II I I \l characters

Вц^ДОЩ = En|i|^x|f|d|k|(| ^ Enigxfdk( ^

Fig. 4. Geometrical annotation for training

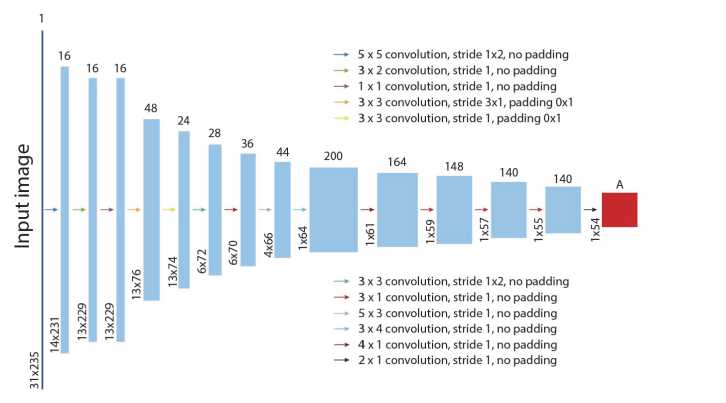

Fig. 5 and Table 1 show the architecture of the proposed FCN that we use in our experiments. We also use ReLU activation function after each convolutional layer. To train the FCN we use images of fixed size Wfixed x H^ixed. For each ideal image we need full geometrical annotation to denote the centers of the characters and cuts on the projection. We have trained our models using GPU Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090. One model takes about 25 hours to train.

Fig. 5. Architecture of the FCN

Tab. 2. FCN Architecture

|

Layer |

Filters |

Stride |

Padding |

Output Size |

|

input |

– |

– |

– |

235 x 31 x 1 |

|

conv |

16, 5x5 |

2x1 |

no |

231 x 14 x 16 |

|

conv |

16, 2x3 |

1x1 |

no |

229 x 13 x 16 |

|

conv |

16, 1x1 |

1x1 |

no |

229 x 13 x 16 |

|

conv |

48, 3x3 |

1x3 |

1x0 |

76 x 13 x 48 |

|

conv |

24, 3x3 |

1x1 |

1x0 |

74 x 13 x 24 |

|

conv |

28, 3x3 |

2x1 |

no |

72 x 6 x 28 |

|

conv |

36, 1x3 |

1x1 |

no |

70 x 6 x 36 |

|

conv |

44, 3x5 |

1x1 |

no |

66 x 4 x 44 |

|

conv |

200, 4x3 |

1x1 |

no |

64 x 1 x 200 |

|

conv |

164, 1x4 |

1x1 |

no |

61 x 1 x 164 |

|

conv |

148, 1x3 |

1x1 |

no |

59 x 1 x 148 |

|

conv |

140, 1x3 |

1x1 |

no |

57 x 1 x 140 |

|

conv |

140, 1x3 |

1x1 |

no |

55 x 1 x 140 |

|

conv |

Л, 1x2 |

1x1 |

no |

54 x 1 x Л |

Restrictions of the approach

In our view, the main limitation of our method is that we need to build a projection of the centers of characters on the horizontal axis (or on the vertical axis if we consider vertical writing). Thus, the approach is not directly suitable for accurate recognition of scripts that combine horizontal and vertical writings, for example, typical Urdu Nastaliq texts are inherently cursive and while the separate words are aligned horizontally, the letters inside one word are often aligned vertically [37]. But we should mention that the approach can be adapted to such scripts if we add ligatures as separate pins.

Datasets

Purely synthetic training data

To train our recognizer we use purely synthetic data without any sensible texts, i.e. using random synthesis of character sequences. The need for synthetics arises from the fact that to train the FCN we need full geometrical annotations with provided coordinates for centers of the characters and the cuts between them. This kind of annotations are not provided in any public natural dataset. Thus, we create a synthetic training dataset using a method described in [38] and later used in [14]. In our experiments we train our models from scratch. Fig. 4 shows the images from the training sample, the first three images are backgrounds, the last three images are the text mask images. It should be mentioned that to make the data more variable we mix the backgrounds and text masks during the online augmentation stage, thus, each text lines can be printed in any background. We also employ a number of standard augmentations such as projective and affine transform, blur and motion blur, various noise, and darkening. For each text line image we automatically acquire the ground truth per line.

Figure 6: Examples from training sample

It is necessary to emphasize that the usage of synthetic images for automatically created ground truth is highly important, as we need exact geometry for characters' borders and cuts between consequent characters.

Public testing datasets

As our target is mobile-based recognition of various documents, we used a public dataset of imitations of ID documents entitled Mobile Identity Document Video dataset, MIDV-500 [10] for short and also used its later extension MIDV-2019 [11] (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Examples of photos of the same ID card from MIDV-500 and MIDV-2019

MIDV-500 originally contains 500 video clips for 50 different types of ID documents, one document per type. As the publication of real ID documents is prohibited in many countries, the authors used the images from public domain, usually the official sample images with names like "SPECIMEN" that are published by governments for public use. Then, the authors split the first 3 seconds of each video into the frame sequences with 10 fps. The ground truth with fields' values and quadrangles for each document and with the quadrangle of the document for each frame are provided. MIDV-2019 is an extension of MIDV-500 that employs the same ID document instances, but provides 200 more video clips with strong projective distortions and low-lightning conditions, that were further divided into frames in the same way as MIDV–500 clips. We did not used any images from MIDV-500, MIDV-2019 or other datasets of documents' images in the training process.

As our main focus is text line recognition, we preprocessed the images from both MIDV–500 and MIDV–2019. As it has already been mentioned, the original images are of ID documents in various backgrounds. For each photo, the datasets contain the ground truth with the coordinates of each corner of the physical object. The ground truth for each ideal document contains information about each field location and its value.

Using provided ground truth we cropped the images of text lines using the following prerequisites:

-

• We know the physical sizes of the ID documents in millimeters, as they are standard for ID cards and passport

-

• We want to extract images with 300 dpi

Thus, we use the following procedure:

-

1. Using the coordinates of the document quadrangle in the image and document's size calculate the projective transform between the distorted and the ideal coordinates

-

2. For each field, using the projective transform and the field's ideal coordinates, calculate its coordinates in the distorted image. We also add 20% padding for each coordinate of the ideal field

-

3. For each field, crop projectively extracted image of the field and save it. Also save corresponding textual value from the ground truth.

We use such an approach to avoid the errors of subsystems employed before the recognition as they could seriously decrease the accuracy, e.g., in [39] the authors achieve only 85.18% accuracy for MRZ while our baseline [14] shows 92.98% accuracy. The exact number of extracted text lines images by type is shown in Tab. 3, where Dates stands for dates printed with digits and punctuation only, Latin names stands for the image of name and surname fields that use only the English alphabet, MRZ stands for machine readable zone images, and Docnum means the images with document numbers. We should emphasize that we do not perform any additional image preprocessing, e.g. binarization, as, firstly, modern recognition models demonstrate competitive results without any image preprocessing, and, secondly, the preprocessing could drastically decrease the readability of the text in the images, for example, in case of a highlight and low-lighting conditions.

Tab. 3. The distribution of text line images in MIDV-500 and MIDV-2019

|

Field |

MIDV – 500 |

MIDV–2019 |

||

|

type |

Images |

Chars |

Images |

Chars |

|

Dates |

17735 |

176142 |

10920 |

108840 |

|

Latin names |

15257 |

131067 |

9240 |

78360 |

|

MRZ |

5096 |

220992 |

3600 |

156480 |

|

Docnum |

9329 |

88294 |

5760 |

54360 |

Experimental setup

In our experiments we would like to cover two important questions. The first one is the influence of the number of synthetic pin's samples in the training process. To be exact, we would like to know if we should add synthetic pin between any two characters thus making the characters' distribution unbalanced or we should balance the number of synthetic pins. The second question is the comparison of the proposed method with the previously published ones. To train the proposed model, we use only the previously described synthetic data. To test all the models we use cropped text line images from MIDV-500 and MIDV-2019. It should be added that in text lines from MIDV-500 and MIDV-2019 the total number of various characters is equal to 70, including digits, punctuation, and capital and small Latin letters. For our experiments, we train case-insensitive classifier and also we unite characters 0 and 0, thus, the final of classes equals 43. It should be mentioned that we also combine 0 and 0 into one class when calculating the metrics, i.e. we do not consider the mix up of 0 and 0 an error, for all the considered methods. We do it to make sure that our method does not have any unjustified advantages. For the proposed method have trained 10 models.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate text recognition accuracy, we calculate the per-character recognition rate PCR [14].

nrn _ ^tal ^'"(.^idealкгесоЛ^Чаеад

rCR — 1--7----:-----7г-----------

- ^ideal)

where Ltota[ denotes the total number of lines, len(l [ideal ) is the length of the i-th line and lev(lil deal , l irecog ) stands for the Levenshtein distance between the recognized text and the ground truth.

The other performance measure we take is time. We measured the total time necessary to recognize the various groups of text line images on CPU AMD Ryzen 7 1700 in one thread. Additionally, we measured time on GPU Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 for TrOCR model.

Baselines

To compare our method with other widely used ones, we selected several methods that cover the three main groups described in Related works. It should be mentioned that we selected the methods developed for documents' recognition, excluding the methods developed for the scene text recognition. We chose 2CNN approach [14] that employs a FCN a segmenter and a CNN as a classifier as this approach is specifically intended for recognition on device and also because the idea of FCN segmenter inspired our research. We use Tesseract OCR 5.3.2, TrOCR-small [28], TrOCR-base [28], and Paddle Ocr v3 [27] recognition module for comparison. We also included previously published results for Tesseract OCR 4.0.0 and ABBYY FineReader 15 into our comparison to emphasize that Tesseract OCR 5.3.2 is a modern and constantly developing OCR system. We do not retrain or fine-tune the baseline models. It should be mentioned that we do not include DTrOCR model [31] as the model is not publicly available.

Experimental results

In Tab. 4 we show that without synthetic pin's examples the recognizer shows poor results ("No synthetic pin" column) and the addition of maximal number of synthetic pin's examples sufficiently increase the results (the "All synthetic" column). Finally, in the middle column entitled "Balanced synthetic" we show the results of the recognizer trained with the described balancing method.

Tab. 4. Text lines recognition results of the proposed method with no synthetic pin examples, balanced number of synthetic examples and the all possible synthetic pin's examples for MIDV-500

|

Text Line type |

No synthetic pin |

Balanced synthetic |

All synthetic |

|

PCR× 100% |

|||

|

Latin names |

65.93 |

82.42 |

73.67 |

|

Dates |

69.18 |

87.15 |

82.81 |

|

MRZ |

87.84 |

94.93 |

94.73 |

|

Docnum |

59.21 |

83.62 |

80.03 |

In Tab. 5 we compare the "balanced synthetic" model with other published models and results. If considering the best of our models, our approach overcomes the 2CNN approach for all the fields, but has a draw with TrOCR [28] in terms of accuracy. While our approach shows the better results for Latin names and MRZ, TrOCR-small is better for documents' number and TrOCR-base is better for Dates. But Tab. 7 shows that while TrOCR shows quality comparable to the proposed method, its performance is drastically slow as it takes 0.29 seconds to recognize one name and 1.13 seconds to recognize one line of MRZ with TrOCR-small model on CPU. This speed is determined by the model itself as vision transformers are recurrent in inference. As a result, while giving promising results, TrOCR cannot be used for "on-device"

recognition systems. To compare the performance on CPU we used AMD Ryzen 7 1700. For TrOCR GPU measurement we used GPU Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090.

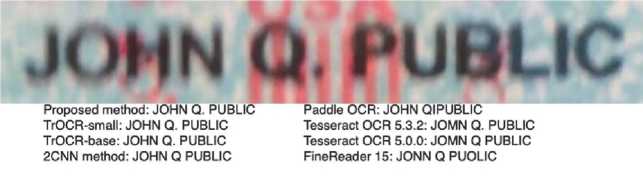

In Tab. 5 we provide sizes of the compared models. According to Tab. 5 and Table 7 the closest model is Paddle OCR that uses tiny transformer-like model. We also should mention that unlike the TrOCR [28] model that is very heavy (its is small version takes 246 MB), the recognizer of Paddle OCR is 9.96 MB against 2.5 MB of our model. Tab. 5 demonstrates that we show better results for MRZ, but Paddle OCR is more accurate in Latin names. In our view, the main reason of this difference is the fact that Paddle OCR recognition model has been trained using real data. As a result, they show better result for text lines that contain most prominent language model as MIDV-500 has sample names like "TEST" and "SPECIMEN" and are inferior to our model on the data that are not presented in typical texts. In Fig. 6 we show the recognition results of the same one text line image with different models. To further compare our recognizer and Paddle OCR we present their PCR on MIDV-2019 in Table 6. MIDV-2019 is an extension of MIDV-500 that contains images with strong distortions typical for camera-captured images, i.e. images with strong projective transform and unstable lighting conditions. On this sample our recognizer overcomes Paddle OCR in all text lines, if considering the best model, except Latin names, but the difference in Latin names recognition is significantly smaller. In case of average accuracy of 10 models, the Docnum fields are recognized better with Paddle OCR, but it should be taken into account that for Paddle OCR one best model was selected and published.

Tab. 5. Sizes of models

|

Model |

Size |

|

Proposed method |

2.5 MB |

|

TrOCR-small[28] |

246 MB |

|

TrOCR-base[28] |

1.33 GB |

|

Tesseract OCR 5.3.2 |

14.7 MB |

|

Tesseract OCR 4.0.0 |

22.4 MB |

|

Paddle OCR v3[27] |

9.96 MB |

Fig. 8. Example of recognition results of different methods

Tab. 6. Text lines recognition results of the proposed method, TrOCR-small, TrOCR-base, 2CNN method, Tesseract OCR 5.3.2 and other previously published results for MIDV-500

|

Text line type |

||||

|

PCR x 100% |

||||

|

Latin names |

Dates |

MRZ |

Docnum |

|

|

Proposed method |

80.39±2.17 |

86.29±0.96 |

94.06 ± 1.23 |

82.57±1.6 |

|

TrOCR-small[28] |

76.88 |

89.34 |

61.01 |

88.43 |

|

TrOCR-base[28] |

78.54 |

89.92 |

62.29 |

88.28 |

|

2CNN method[14] |

79.04 |

84.59 |

92.98 |

80.06 |

|

Paddle OCR v3[27] |

87.26 |

87.80 |

92.40 |

86.72 |

|

Tesseract OCR 5.3.2 |

74.98 |

74.50 |

58.01 |

70.55 |

|

Tesseract OCR 4.0.0 |

75.44 |

57.80 |

47.94 |

41.83 |

|

FineReader 15 |

55.76 |

56.67 |

74.11 |

57.11 |

Tab. 7. Text lines recognition results of the proposed method and Paddle OCR for MIDV-2019

|

Text line type |

||||

|

PCR × 100% |

||||

|

Latin names |

Dates |

MRZ |

Docnum |

|

|

Proposed method |

77.13 ± 1.78 |

85.12 ± 0.48 |

88.95 ± 0.98 |

76.95 ± 0.76 |

|

Paddle OCR v3[27] |

79.60 |

81.48 |

81.33 |

76.68 |

Conclusion

In our paper, we have presented an approach to the recognition of text lines images that were captured in uncontrolled conditions, for example, with a camera of a smartphone. The core idea of approach is the usage of the fully convolutional neural network with a special synthetic pin that denotes the cuts between the consecutive characters to build a projection of the image on the horizontal axis and further usage of dynamic programming to analyze the projection and build the answer. As we use purely synthetic training data we do not need any expensive manual annotations. Our approach is suitable for the on-the-device systems as it employs a tiny FCN that is performance- and memory-efficient. According to the experiments performed on target datasets, our approach has overcome the majority of popular models in accuracy and has overcome all of them in the trade-off between of accuracy and time and memory consumption. Moreover, as the baselines models use 32-bit floating point numbers for weights we measured our model in the same way, i.e. its weights were presented with 32-bit floating point numbers. But, in fact, our model can be successfully quantized to 8-bit integer weights and will be smaller than 650 KB. Also, as our approach does not employ any language models, we suppose that additional usage of dictionaries or addition of human-readable texts into the training data could further enhance the resulting model. Moreover, in our experiments we analyzed the influence of the number of the examples of synthetic pin in training sample on the resulting accuracy of the model and showed that our proposed method for data balancing is efficient. In our future work, we plan to further analyze the influence of training data distribution on the accuracy of the model and to perform experiments for texts in other writing systems, including Chinese and Arabic.

Tab. 8. Total time required for all images recognition for each field in MIDV-500

|

Total time (seconds) |

||||

|

Latin names |

Dates |

MRZ |

Docnum |

|

|

Proposed method |

92.63 ± 2.31 |

108.12 ± 2.47 |

199.57 ± 3.24 |

60.89 ± 1.98 |

|

TrOCR-small[28]-GPU |

473.31 |

553.62 |

683.64 |

291.03 |

|

TrOCR-base[28]-CPU |

22849.21 |

28019.77 |

40698.67 |

12879.91 |

|

TrOCR-base[28]-GPU |

824.11 |

1033.14 |

1068.42 |

472.85 |

|

2CNN method[14] |

112.70 |

121.76 |

233.18 |

110.07 |

|

Paddle OCR v3[27] |

194.40 |

207.88 |

184.36 |

120.41 |

|

Tesseract OCR 5.3.2 |

210.32 |

268.40 |

437.75 |

163.39 |

|

Tesseract OCR 4.0.0 |

304.27 |

371.91 |

586.81 |

227.96 |