Enhancing heavy metal cleanup: microbial-assisted phytoremediation by Alternanthera ficoidea (L.) P. Beauv.

Автор: Florips Thomas, Akshaya Prakash C., Fathima Mishiriya V., Kadeeja Beebi P., Sebastian Delse P.

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In the era of sustainable development, phytoremediation has emerged as a promising, eco-friendly strategy for reclaiming heavy metal-contaminated environments. This study explores the phytoremediation potential of Alternanthera ficoidea for cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) and investigates the role of beneficial microbes-Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Trichoderma viride-in enhancing metal uptake. Remarkably, the roots of plants treated with Cd + Azotobacter sp. exhibited a 173% increase in Cd accumulation compared to Cd-only treatments. Even more striking, Cd accumulation in the shoots surged by 1025% in plants treated with Cd + T. viride. Conversely, microbial inoculation significantly reduced Pb accumulation in both roots and shoots of A. ficoidea. Bioaccumulation (BCF) and translocation factor (TF) analyses revealed that microbial augmentation, particularly with Azotobacter sp., enhanced the phytostabilization capacity of A. ficoidea for Cd. Additionally, the species demonstrated inherent potential for Pb phytostabilization. These findings underscore the synergistic benefits of combining phytoremediation with microbial assistance for the sustainable detoxification of heavy metal-laden soils.

Heavy metals, cadmium, lead, azotobacter sp, p. fluorescens, t. viride

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143184736

IDR: 143184736

Текст научной статьи Enhancing heavy metal cleanup: microbial-assisted phytoremediation by Alternanthera ficoidea (L.) P. Beauv.

Soil is an abiotic factor which is rudimentary for most of the plants as it acts as a substrate for anchorage and absorption of nutrients and minerals (Mishra et al. , 2016). Among the various pollutants that are released into the environment, heavy metals exert severe toxic effects. A metal species might be regarded a "contaminant" if it is present in an undesired location or in a concentration or form that has a negative impact on people or the environment (McIntyre, 2003). Normally heavy metal phytotoxicity in living organisms result from changes in numerous physiological processes caused at cellular/molecular level by inactivating enzymes, blocking functional groups of metabolically important molecules, displacing or substituting for essential elements and disrupting membrane integrity. The effect of heavy metal poisoning in plants is their interference with electron transport activities, especially that of chloroplast membranes resulting in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Vecchia et al. , 2005; Pagliano et al. , 2006).

The most common heavy metals that contaminate the environment are Cd, Cr, Hg, Pb, Cu, Zn, and As. Cadmium and lead, are the heavy metals that do not have any physiological function in living organisms and are considered as toxicants (Sinicropi et al. , 2010). Anthropogenic activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels, effluents generated from landfill sites, agricultural land, and mining waste, especially from zinc and lead mines, leads to increased cadmium contamination in the environment (Thompson & Bannigan, 2008). Cadmium is also used in the manufacturing of Ni-Cd batteries (Genchi, 2020) in cadmium plating baths, electrodes for storage batteries, catalysts, and ceramic glazes ( okhande et al. , 2004).

In plants, cadmium can cause changes in the uptake of minerals through its effects on the availability of minerals from the soil (Moreno et al. , 1999). It has been shown to interfere with the uptake, transport, and use of several elements (Ca, Mg, P, and K) and water by plants (Das et al. , 1997). After prolonged exposure to Cd, the root becomes necrotic, decayed, and mucilaginous, which reduces the elongation of plant roots and shoots and results in leaf rolling and chlorosis (Abbas et al. ,

-

2018). Chlorosis and stunted growth are the readily identifiable symptoms caused by toxicity of Cd in plants (Jali et al. , 2016), and it indirectly contributes to the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the chloroplasts of leaves (Gallego et al. , 2012).

Sources of Pb pollution, apart from natural weathering, are exhaust fumes of automobiles, chimneys of factories using Pb, effluents from the storage battery industry, mining and refining of Pb ores, metal plating and finishing operations, fertilizers, pesticides, and additives in pigments and gasoline (Eick et al. , 1999). In plants, Pb toxicity can result in stunted growth, chlorosis, and blackening of the root system. It inhibits photosynthesis, upsets mineral nutrition and water balance, changes hormonal status, and affects membrane structure and permeability (Sharma & Dubey, 2005). Many technologies such as the removal of contaminated material and chemical or physical treatment, are expensive and do not produce an attractive or long-lasting solution to clean up heavy metal-contaminated soil (Mulligan et al. , 2001; Cao et al. , 2002). However, phytoremediation can offer an affordable, durable, and aesthetically pleasing solution for the remediation of contaminated sites (Ma et al. ,2001).

Phytoremediation has the capability to provide a green, cost-effective, eco-friendly, and feasible application to address some of the world’s environmental challenges (Newman et al. , 2023). ‘Phytoremediation’ consists of the Greek prefix phyto (plant), attached to the atin root remedium (to correct or remove an evil) (Cunningham et al. , 1997). Phytoremediation utilizes many mechanisms including degradation (rhizo-degradation, phytodegradation), accumulation (phytoextraction, rhizofiltration), dissipation (phytovolatilization), and immobilization (hydraulic control and phytostabilization) to degrade, remove, or immobilize the pollutants (Pivetz, 2001).

Phytoextraction involves the uptake and accumulation of metals in plant shoots, which can subsequently be harvested and removed from the area (Anton & Mathe-Gasper, 2005; Nissim et al., 2018). Phytostabilization is another application of phytoremediation in which plants are used to reduce metal mobility in contaminated soils (Jung & Thornton, 1996; Rosselli et al., 2003). Phytovolatilization uses plants to absorb toxic elements from the soil, change them into less toxic volatile forms, and then release the altered forms into the atmosphere by transpiration through the leaves or foliage system of the plant (Mahar et al., 2016). Phytofiltration is the process of removing pollutants from contaminated surface waters or wastewaters by using plant roots (rhizofiltration), shoots (caulofiltration), or seedlings (blastofiltration) (Mesjasz-Przybyłowicz et al., 2004).

In the phytoremediation techniques adopted, the extent of heavy metal accumulation is measured based on two parameters: bioconcentration factor (BCF) and translocation factor (TF). BCF is calculated by dividing the quantity of heavy metal in root by that in soil (Yoon et al. , 2006). Similarly, TF is calculated by dividing the quantity of heavy metal in shoot by that in root (Kumar & Maiti, 2014). If both BCF and TF values are greater than one, the plant is suitable for phytoextraction. If the BCF value is greater than one and the TF value is less than one, the plant is suitable for phytostabilization. If both these values are lower than one, the plant is not appropriate for phytoremediation.

Even though phytoremediation is an efficient method for environmental cleanup, the process typically takes a long time, and the application of it is restricted by the quality of the soil, the weather, and the phytotoxicity of the pollutants. Therefore, to ensure maximum metal harvest from contaminated sites in limited time, microbial-assisted phytoremediation can be applied, which helps in enhancing the pace of environmental cleanup. Microbes can reduce the metal phytotoxicity and stimulate plant growth indirectly by inducing the defense mechanisms, or directly by the solubilization of different mineral nutrients, the production of phytohormones, and the secretion of enzymes (Ma et al. , 2016).

Pseudomonas fluorescens belongs to Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR), an important group of bacteria that play a major role in plant growth promotion, induced systemic resistance, biological control of pathogens, etc. Enhancement of plant growth promotion and reduction of various diseases have been exhibited by various strains of P. fluorescens (Ganeshan & Kumar, 2005). Trichoderma spp. application to the plant rhizosphere promotes the growth of plant morphological traits such as root-shoot length, biomass, height, number of leaves, tillers, branches, fruits, etc. (Halifu et al., 2019;

Alternanthera ficoidea ( .) P. Beauv., commonly called as ‘Fig Joyweed,’ which belongs to the family Amaranthaceae, is a common and widespread plant throughout the tropics and is being increasingly regarded as an invasive weed (Abbasi & Tauseef, 2018). Even though a number of studies have been conducted to identify the heavy metal phytoremediation potential of this plant, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted with the aim of enhancing the heavy metal phytoremediation potential of A. ficoidea using microbes like Pseudomonas fluorescens , Trichoderma viride , and Azotobacter sp. Taking all these factors into account, the present study was conducted to analyse the effect of the microbes Pseudomonas fluorescens , Trichoderma viride , and Azotobacter sp. on Cd and Pb accumulation in A. ficoidea . Additionally, the effect of these heavy metals and nanoparticles on growth parameters, moisture content, and tolerance index were also evaluated to identify the stress response of A. ficoidea .

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

The plant material used for the present study was Alternanthera ficoidea ( .) P. Beauv., of the family Amaranthaceae.

Experimental Design

Plant materials were collected by field exploration from Devagiri, Kozhikode, and they were acclimatized in the Botanical Garden of St. Joseph’s College (Autonomous), Devagiri, Kozhikode, Kerala, India, for a period of one month. The stem cuttings from these plants were transferred into grow bags containing one kilogram of garden soil. The plants were left to root and grow in this mixture for a period of 2 weeks. After rooting, the plants were subjected to heavy metal and microbial biofertilizers (Table 1).

Experimental Procedure

The treatments and treatment combinations included control plants (to which no heavy metals or microbial fertilizers were provided), Cd-treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg CdCl₂ was provided), Pb-treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg PbCl₂ was provided), Azotobacter sp.-treated plants (to which 800 mg/kg Azotobacter sp. was provided), P. fluorescens -treated plants (to which 800 mg/kg P. fluorescens was provided), T. viride -treated plants (to which 800 mg/kg T. viride was provided), autoclaved Azotobacter sp.-treated plants (to which 800 mg/kg autoclaved Azotobacter sp. was provided), autoclaved P. fluorescens -treated plants (to which 800 mg/kg autoclaved P. fluorescens was provided), autoclaved T. viride -treated plants (to which 800 mg/kg autoclaved T. viride was provided), Cd + Azotobacter sp.-treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg CdCl₂ and 800 mg/kg Azotobacter sp. were provided), Cd + P. fluorescens -treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg CdCl₂ and 800 mg/kg P. fluorescens were provided), Cd + T. viride -treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg CdCl₂ and 800 mg/kg T. viride were provided), Pb + Azotobacter sp.-treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg PbCl₂ and 800 mg/kg Azotobacter sp. were provided), Pb + P. fluorescens -treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg PbCl₂ and 800 mg/kg P. fluorescens were provided), Pb + T. viride -treated plants (to which 100 mg/kg PbCl₂ and 800 mg/kg T. viride were provided), and the duration of treatment was one month. All the treatments and treatment combinations are provided in Table 1.

Growth Parameters

After a month of treatment, plant samples were carefully harvested and washed with distilled water. The root and shoot lengths were measured with a graduated scale. The fresh and dry weights of roots and shoots were recorded using an electronic weighing balance. For dry weight measurements, the weighed samples were dried in a hot air oven at 100°C for 1 h, and later the temperature was set at 60°C, in a hot air oven, until the weight attained a constant value.

Moisture Content

The moisture content was determined by measuring the fresh and dry weights of the plants ( okhande et al. , 2011). Tissue moisture content percentage was calculated using the following equation:

Moisture content (MC) % = [(Fresh Weight – Dry Weight)/Fresh Weight] × 100

Tolerance Index (TI)

The tolerance index (TI) of Alternanthera ficoidea under heavy metal and microbial biofertilizers was estimated using the given formula (Rabie, 2005):

TI = (Dry weight of treated plants / Dry weight of control plants) × 100

Accumulation of Cd and Pb

The dried plant samples were ground into a powder. The preparation of the samples for the heavy metal analysis was carried out following Allan's (1969) method. Accurately weighed 0.5 g of powdered roots and shoots from each treatment were digested with 40 ml of nitric acid (HNO₃). After the mixtures were dried out by evaporation, they were extracted using distilled water. The solutions were then boiled, filtered, and made up to 50 ml. The metal ion concentrations were analysed by atomic absorption spectrophotometer at KFRI (Kerala Forest Research Institute), Peechi, Thrissur, Kerala.

Evaluation of Phytoremediation Parameters

The parameters determining the phytoremediation efficiency of the plants, BCF, TF, and BAF, were calculated by the following equations:

-

• BCF = (Heavy metal in root) / (Heavy metal in soil) (Yoon et al. , 2006)

-

• TF = (Heavy metal in shoot) / (Heavy metal in root) (Kumar & Maiti, 2014)

BAF = (Heavy metal in whole plant) / (Heavy metal in soil) (Aladesanmi et al. , 2019)

RESULTS

Effect of Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on Cd, and Pb accumulation in Alternanthera ficoidea

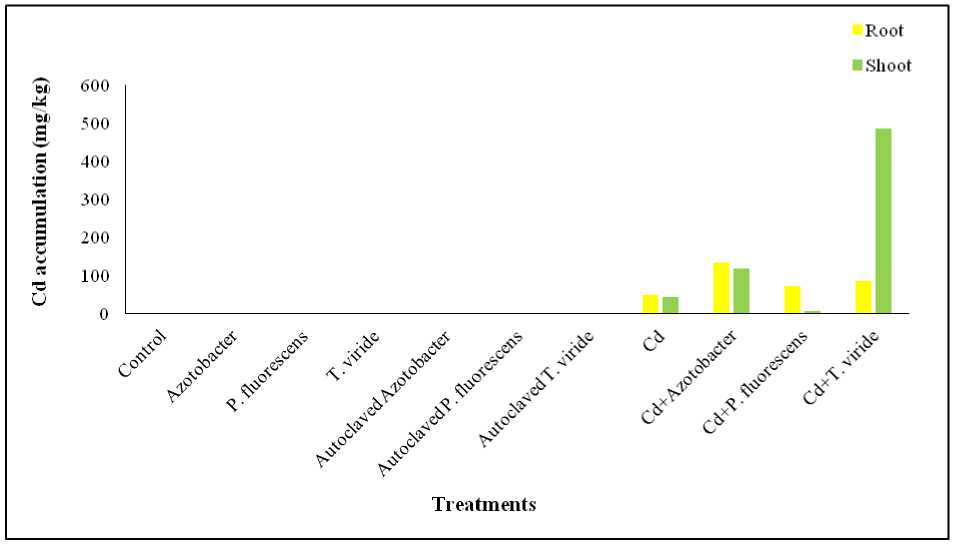

Effect on Cd Accumulation: Cadmium (Cd) accumulation in the control and microbe-only treated A. ficoidea plants was below detectable levels, indicating an uncontaminated soil. Cd accumulation was highest in the roots of Cd + Azotobacter sp. treated plants and in the shoots of Cd + T. viride treated plants. Relative to Cd-only treated roots, Cd + Azotobacter sp. increased Cd accumulation by 173%, T. viride by 78%, and P. fluorescens by 52%. For shoots, Cd + T. viride increased Cd accumulation by 1025%, Azotobacter sp. by 170%, whereas P. fluorescens reduced it by 82% (Figure 1).

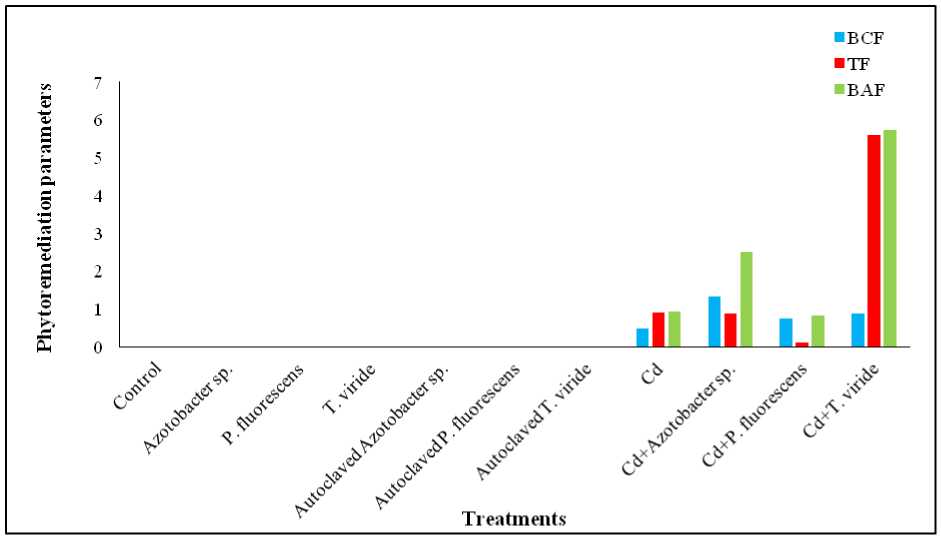

Bioconcentration factor (BCF) values were below one, except for Cd + Azotobacter sp. (1.325), indicating limited accumulation. The Bioaccumulation factor values (BAF) exceeded one in both Cd + Azotobacter sp. (2.41) and Cd + T. viride (5.72) treated plants, while TF value exceeded one only in Cd + T. viride treated plants (5.6). The BCF order was: Cd + Azotobacter sp. > Cd + T. viride > Cd + P. fluorescens > Cd. TF values followed: Cd + T. viride > Cd > Cd + Azotobacter sp . > Cd + P. fluorescens . Bioaccumulation factor (BAF) was highest in Cd + T. viride (Figure 2).

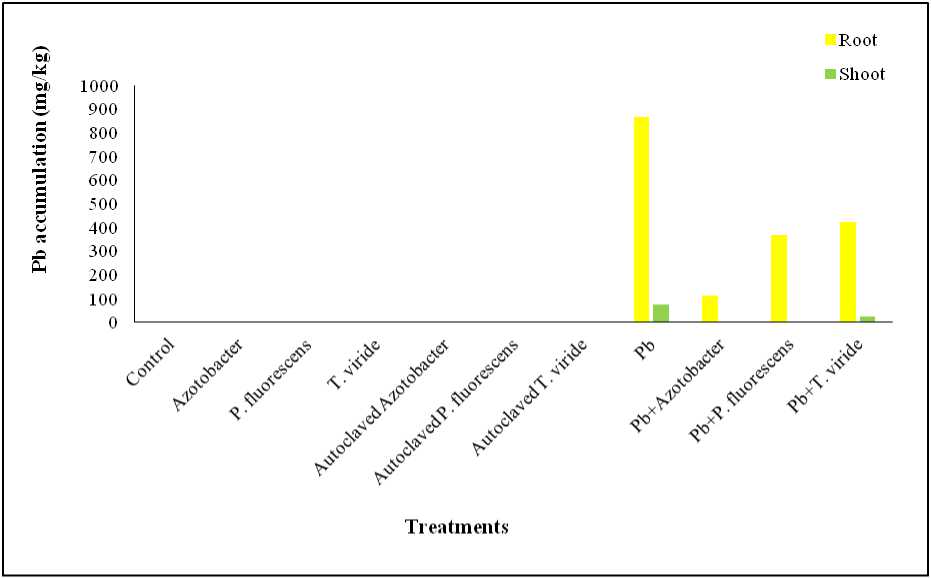

Effect on Pb Accumulation: ead (Pb) accumulation was also below detection in control and microbe-only treatments. The highest root Pb accumulation occurred in Pb-only treated plants (865 mg/kg). In microbial co-treatments, root Pb levels decreased by 87% ( Azotobacter sp.), 57% ( P. fluorescens ), and 51% ( T. viride ). Shoot Pb was undetectable in Pb + Azotobacter sp. and Pb + P. fluorescens , and reduced by 70% in Pb + T. viride (Figure 3).

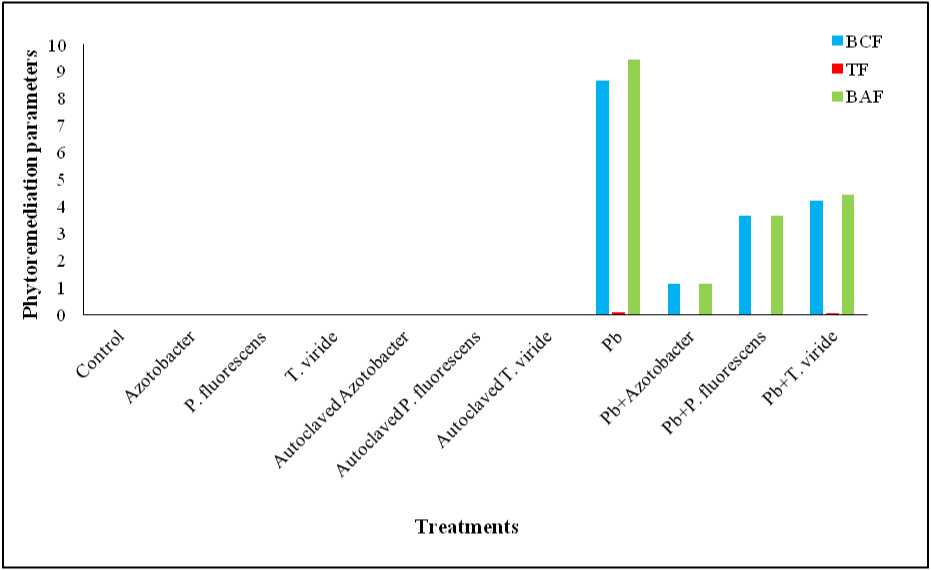

All Pb-treated plants had BCF >1, with highest in Pb-only treatment. BCF ranking: Pb > Pb + T. viride > Pb + P. fluorescens > Pb + Azotobacter sp. All treatments had TF <1, highest in Pb-only (0.089) (Figure 4).

Effect on Growth Parameters

Cd and Microbial Influence: Root length increased by 3% only in Azotobacter sp. treated plants. Cd treatment reduced root length by 69%. Cd + Azotobacter sp., Cd + P. fluorescens, and Cd + T. viride improved root length over Cd alone by 40%, 58%, and 56%, respectively.

Shoot length slightly increased by 1% in P. fluorescens treatment. Cd reduced shoot length by 37%. Cd + Azotobacter sp., Cd + P. fluorescens , and Cd + T. viride improved shoot length by 20%, 22%, and 24% over Cd.

Fresh root weight decreased across treatments. Compared to Cd, Cd + Azotobacter sp., Cd + P. fluorescens, and Cd + T. viride increased root fresh weight by 18%, 22%, and 46%, respectively. Dry root weight increased by 40%, 30%, and 50% in the same order.

Shoot fresh weight increased by 29%, 27%, and 19%, while shoot dry weight increased by 40%, 30%, and 50% for Cd + Azotobacter sp., Cd + P. fluorescens , and Cd + T. viride , respectively, over Cd (Table 2).

Pb and Microbial Influence: Only Azotobacter sp. increased root length by 3% over control. Pb reduced root length by 59%. Pb + Azotobacter sp. and Pb + T. viride improved root length by 15% and 24% over Pb. No change in Pb + P. fluorescens .

Shoot length increased only in P. fluorescens treatment (1%). Pb reduced it by 33%. Pb + Azotobacter sp., Pb + T. viride , and Pb + P. fluorescens improved it by 24%, 24%, and 18% over Pb.

Fresh root weight decreased across treatments. Compared to Pb, Pb + Azotobacter sp., Pb + P. fluorescens, and Pb + T. viride reduced root fresh weight by 28%, 9%, and 6%, respectively. However, dry weights increased by 90%, 81%, and 54%, respectively.

Shoot fresh weight decreased in all treatments. Compared to Pb, Pb + Azotobacter sp., Pb + P. fluorescens , and Pb + T. viride reduced shoot fresh weight by 37%, 17%, and 16%. Shoot dry weight increased by 70%, 62%, and 46%, respectively (Table 3).

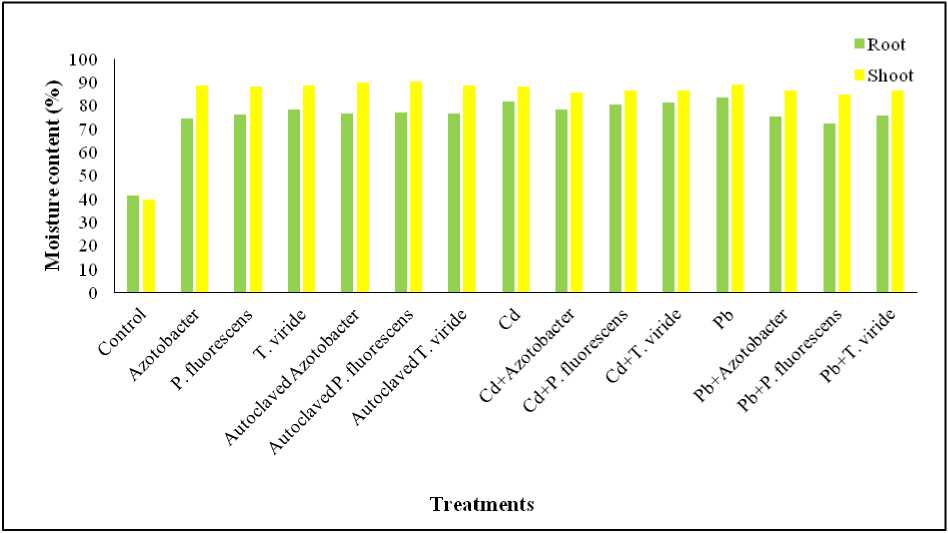

Moisture content of roots of control and treated plants in their decreasing order are : Pb treated > Cd treated > Cd + T. viride treated > Cd + P. fluorescens treated > Cd + Azotobacter sp. treated > T. viride treated > autoclaved P. fluorescens treated > autoclaved T. viride treated > autoclaved Azotobacter sp. treated > P. fluorescens treated > Pb + T. viride treated > Pb + Azotobacter sp. treated > Azotobacter sp. treated > Pb + P. fluorescens treated > Control A. ficoidea plants.

The moisture content of shoots of control and treated plants in their decreasing order is as follows: Autoclaved P. fluorescens treated > Autoclaved Azotobacter sp. treated > Pb treated > T. viride treated > Autoclaved T. viride treated > Azotobacter sp. treated > P. fluorescens treated > Cd treated > Cd + P. fluorescens treated > Cd + T. viride treated > Pb + T. viride treated > Pb + Azotobacter sp. treated > Cd + Azotobacter sp. treated > Pb + P. fluorescens treated > Control A. ficoidea plants (Figure 5).

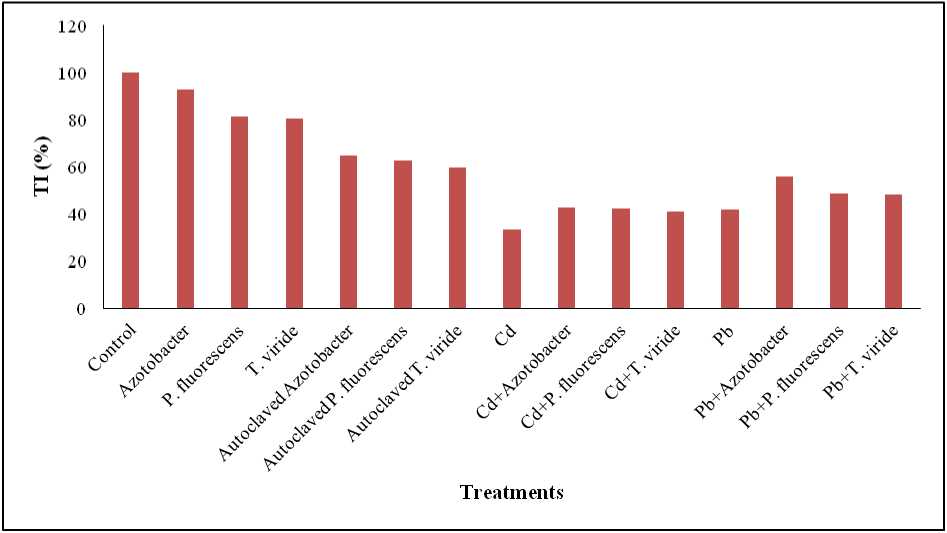

Tolerance Index (TI) is a measure of relative tolerance of plants to metal toxicity (Ismail et al. , 2013). The plants having TI > 60% or TI > 1 show increased metal tolerance potential ( ux et al. , 2004). In the present study, tolerance index of plants decreased in the order: Control > Azotobacter sp. treated > P. fluorescens treated > T. viride treated > Autoclaved Azotobacter sp. treated > Autoclaved P. fluorescens treated > Autoclaved T. viride treated > Pb + Azotobacter sp. treated > Pb + P. fluorescens treated > Pb + T. viride treated > Cd + Azotobacter sp. treated > Cd + P. fluorescens treated > Pb treated > Cd + T. viride treated > Cd treated A. ficoidea plants (Figure 6).

The plants did not exhibit any visual toxic symptoms either in the leaves or in the stem. All plants grew well in the contaminated environment without wilting. Moreover, chlorosis was not observed.

Table 1. - Various Treatment Combinations of Heavy Metals and Microbes

|

Plant |

Treatment Combinations |

Cd (mg/kg) |

Pb (mg/kg) |

Azotobact er sp . (mg/kg) |

P. fluorescen s (mg/kg) |

T. viride (mg/kg) |

|

A. ficoidea |

Control |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Azotobacter sp. |

- |

- |

800 |

- |

- |

|

|

P. fluorescens |

- |

- |

- |

800 |

- |

|

|

T. viride |

- |

- |

- |

- |

800 |

|

|

Autoclaved Azotobacter sp. |

- |

- |

800 |

- |

- |

|

|

Autoclaved P. fluorescens |

- |

- |

- |

800 |

- |

|

|

Autoclaved T. viride |

- |

- |

- |

- |

800 |

|

|

Cd |

100 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Cd+ Azotobacter sp. |

100 |

- |

800 |

- |

- |

|

|

Cd+ P. fluorescens |

100 |

- |

- |

800 |

- |

|

|

Cd+ T. viride |

100 |

- |

- |

- |

800 |

|

|

Pb |

- |

100 |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Pb+ Azotobacter sp. |

- |

100 |

800 |

- |

- |

|

|

Pb+ P. fluorescens |

- |

100 |

- |

800 |

- |

|

|

Pb+ T. viride |

- |

100 |

- |

- |

800 |

Table 2. Effect of Cd, Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the growth parameters of Alternanthera ficoidea

|

Sl No |

Treatments |

Root length (cm) |

Shoot length (cm) |

Fresh weight (g) |

Dry weight (g) |

||

|

Root |

Shoot |

Root |

Shoot |

||||

|

1 |

Control |

20.33±6.80 |

54.33±2.08 |

1.43±0.18 |

11.02±4.81 |

0.84±0.15 |

6.66±3.03 |

|

2 |

Cd |

6.16±2.02 |

34.00±8.71 |

0.54 |

3.60±1.78 |

0.10±0.05 |

0.43±0.22 |

|

3 |

Azotobacter sp. |

21.00±5.00 |

53.33±11.54 |

1.24±0.36 |

10.3±8.96 |

0.32±0.09 |

1.21±0.94 |

|

4 |

P. fluorescens |

11.33±3.21 |

55.00±5.00 |

1.2±0.12 |

8.92±1.76 |

0.29±0.05 |

1.05±0.11 |

|

5 |

T. viride |

17.00±15.62 |

51.66±7.63 |

1.14±0.49 |

8.89±2.64 |

0.25±0.13 |

1.02±0.13 |

|

6 |

Autoclaved Azotobacter sp. |

11.16±6.04 |

48.00±6.00 |

1.10±0.09 |

6.93±1.87 |

0.26±0.13 |

0.71±0.12 |

|

7 |

Autoclaved P. fluorescens |

11.00±2.64 |

49.00±5.56 |

1.04±0.52 |

6.75±3.40 |

0.24±0.02 |

0.66±0.24 |

|

8 |

Autoclaved T. viride |

9.33±4.16 |

48.5±23.33 |

1.02±0.13 |

6.41±1.80 |

0.24±0.03 |

0.75±0.34 |

|

9 |

Cd + Azotobacter sp. |

8.66±2.51 |

41.00±11.00 |

0.64±0.39 |

4.65±2.38 |

0.14±0.02 |

0.67±0.21 |

|

10 |

Cd + P. fluorescens |

9.75±1.76 |

41.66±12.74 |

0.66±0.11 |

4.58±1.99 |

0.13±0.03 |

0.62±0.39 |

|

11 |

Cd + T. viride |

9.66±2.08 |

42.33±19.13 |

0.79±0.34 |

4.29±1.52 |

0.15±0.07 |

0.59±0.33 |

Table 3. Effect of Pb, Azotobacter sp. , Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the growth parameters of Alternanthera ficoidea

|

Sl No |

Treatments |

Root length (cm) |

Shoot length (cm) |

Fresh weight (g) |

Dry weight (g) |

||

|

Root |

Shoot |

Root |

Shoot |

||||

|

1 |

Control |

20.33±6.80 |

54.33±2.08 |

1.43±0.18 |

11.02±4.81 |

0.84±0.15 |

6.66±3.03 |

|

2 |

Pb |

8.33±2.08 |

36.00±5.19 |

0.66±0.12 |

4.52±2.23 |

0.11±0.05 |

0.50±0.17 |

|

3 |

Azotobacter sp. |

21.00±5.00 |

53.33±11.54 |

1.24±0.36 |

10.3±8.96 |

0.32±0.09 |

1.21±0.94 |

|

4 |

P. fluorescens |

11.33±3.21 |

55.00±5.00 |

1.2±0.12 |

8.92±1.76 |

0.29±0.05 |

1.05±0.11 |

|

5 |

T. viride |

17.00±15.62 |

51.66±7.63 |

1.14±0.49 |

8.89±2.64 |

0.25±0.13 |

1.02±0.13 |

|

6 |

Autoclaved Azotobacter sp. |

11.16±6.04 |

48.00±6.00 |

1.10±0.09 |

6.93±1.87 |

0.26±0.13 |

0.71±0.12 |

|

7 |

Autoclaved P. fluorescens |

11.00±2.64 |

49.00±5.56 |

1.04±0.52 |

6.75±3.40 |

0.24±0.02 |

0.66±0.24 |

|

8 |

Autoclaved T. viride |

9.33±4.16 |

48.50±23.33 |

1.02±0.13 |

6.41±1.80 |

0.24±0.03 |

0.75±0.34 |

|

9 |

Pb + Azotobacter sp. |

9.66±3.51 |

44.66±11.01 |

0.85±0.37 |

6.11±1.80 |

0.21±0.11 |

0.85±0.28 |

|

10 |

Pb + P. fluorescens |

8.33±2.08 |

42.66±6.42 |

0.72±0.65 |

5.32±2.29 |

0.2±0.11 |

0.81±0.48 |

|

11 |

Pb + T. viride |

10.33±3.51 |

44.66±5.50 |

0.70±0.30 |

5.27±1.61 |

0.17±0.16 |

0.73±0.13 |

Figure 1. Effect of Azotobacter sp. , P. fluorescens and T. viride on Cd accumulation in Alternanthera ficoidea

Figure 2. Effect of Azotobacter sp., P. fluorescens and T. viride on BCF, TF and BAF values of Cd in A. ficoidea

Figure 3. Effect of Azotobacter sp., P. fluorescens and T. viride on Pb accumulation in A. ficoidea

Figure 4. Effect of Azotobacter sp., P. fluorescens and T. viride on BCF, TF and BAF values of Pb in Alternanthera ficoidea

Figure 5. Effect of heavy metals (Cd, & Pb) and Azotobacter sp ., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the moisture content of Alternanthera ficoidea

Figure 6. Effect of heavy metals (Cd, & Pb), Azotobacter sp. , Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the tolerance index of Alternanthera ficoidea

DISCUSSION

Effect of Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on Cd accumulation in Alternanthera ficoidea

Studies have shown that Trichoderma, Azotobacter sp. and Pseudomonas have mediated the enhanced accumulation of Cd in plants (Panwar et al., 2011; Song et al., 2015). Similarly, the present study has also witnessed enhanced accumulation of Cd in Cd + Azotobacter sp. and Cd + T. viride treated plants. However, decreased accumulation of Cd was observed in the shoots of Cd + P. fluorescens treated A. ficoidea. This may be because Pseudomonas might have immobilized Cd in the root or rhizosphere, thereby causing a reduction in the uptake of Cd by plants (Wu et al., 2022).

Effect of Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on Pb accumulation in Alternanthera ficoidea

Plants with BCF values greater than one and TF values lesser than one are potential phytostabilizers (Yoon et al. , 2006). Hence, the present study reports A. ficoidea as a suitable plant for Pb phytostabilization. The highest BAF value was observed in A. ficoidea plants treated solely with Pb. This confirms that the application of microbes has decreased the accumulation of Pb in the plant. The effective role played by microbes in reduction of metal uptake is mainly due to immobilization that results in binding the metal to root by complex formation, which further prevents its translocation towards shoot (Khanna et al. , 2019).

Effect of heavy metals (Cd, Pb) and Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the growth parameters of Alternanthera ficoidea

Effect of Cd and Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the growth parameters of Alternanthera ficoidea

The present study observed a significant decline in the growth parameters of Cd treated plants when compared to the control plant. Similar results due to Cd toxicity in plants were reported by Ci et al. (2009) and Faizan et al. (2012). Shukla et al. (2003) discussed the reduction in growth parameters due to the interference of Cd in nutrient uptake and altered levels of various biochemical constituents like proteins, amino acids, etc. The results obtained in the present study may also be due to these reasons. Enhanced growth of Cd + microbe treated plants compared to Cd-only treated A. ficoidea may be due to the stress-mitigating effect of microbes on the plants. The results of the present study are corroborative with the report of Rawat et al. (2012), who observed that Trichoderma could improve plant growth under stressful conditions.

Effect of Pb and Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the growth parameters of Alternanthera ficoidea

The present study observed decreased growth parameters in Pb treated A. ficoidea compared to the control plants. Various studies have reported growth reduction in plants subjected to heavy metal stress. A study conducted by Hussain et al. (2021) found that Pb stress significantly halted growth (stem and root length), biomass (fresh and dry), and total water content in Persicaria hydropiper compared to plants grown in Pb-free medium. Ekmekçi et al. (2009) reported that plant growth retardation by metal stress is due to water deficit resulting from disturbance of water balance. The same reason may be applicable to the present case also. However, application of microbes enhanced the growth parameters of Pb-stressed A. ficoidea plants. The results of the present study align with the report of Rawat et al. (2012), who observed that Trichoderma could improve plant growth under stressful conditions. Further studies are required to clarify the reasons behind such responses in plants.

Effect of heavy metals (Cd, & Pb) and Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the moisture content of Alternanthera ficoidea

With the excess concentration of heavy metals, decrease in transpiration and moisture content of the plants were observed by Kastori et al. (1992). However, our study revealed contradictory results. Further studies are required to clarify the reasons for obtaining such results.

Effect of heavy metals (Cd, & Pb) and Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride on the tolerance index of Alternanthera ficoidea

The current study observed decreased TI in Cd treated, Pb treated, Cd + microbe treated and Pb + microbe treated plants compared to the control plants. This indicates that heavy metals have imposed stress on A. ficoidea plants. However, compared to the heavy metal-only treated plants, heavy metal + microbe treated A. ficoidea plants exhibited enhanced TI. This points out the heavy metal stress-relieving ability of the microbes Azotobacter sp., P. fluorescens and T. viride on A. ficoidea plants.

Visual toxic effects of heavy metals (Cd, & Pb) and Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma viride in Alternanthera ficoidea

The concentration of heavy metal in the soil might be too low for the plant to exhibit toxicity symptoms or it may be because the plant is tolerant towards heavy metal stress. Further studies are required to explore the reason behind this observation.

CONCLUSION

In the era of sustainability, phytoremediation plays a major role to rebuild the polluted areas. Phytoremediation is a natural way of finding a solution to reduce the increasing pollution in soils. The present study was conducted to investigate the accumulation efficiency of the heavy metals Cadmium (Cd) and ead (Pb) by the microbial assistance of Azotobacter sp., P. fluorescens and T. viride in Alternanthera ficoidea. The effect of heavy metals and the microbes on the growth parameters, moisture content and tolerance index were also analysed.

The results revealed that A. ficoidea could accumulate Pb effectively in its root and hence can be used as an efficient plant for Pb phytostabilization. Application of microbes Azotobacter sp., P. fluorescens and T. viride enhanced the accumulation of Cd in the roots of A. ficoidea plants with respect to plants treated with Cd alone. Upon applying the microbe Azotobacter, plants treated with Cd + Azotobacter sp. showed Cd phytostabilization potential. Accumulation of lead was decreased in the roots and shoots of all plants that were treated with microbes. Therefore, we identified that Azotobacter sp., P. fluorescens and T. viride can be used for enhancing the Cd accumulation in A. ficoidea. However, opposite results were observed in the case of Pb. The findings demonstrated that Azotobacter sp., T. viride, and P. fluorescens could decrease the accumulation of Pb in A. ficoidea probably by immobilizing the heavy metal in the rhizosphere, thus helping in decreasing the risk of food chain contamination.

The growth parameters of plants treated with Cd + Azotobacter sp., Cd + P. fluorescens and Cd + T. viride, Pb + Azotobacter sp. , Pb + P. fluorescens and Pb + T. viride increased remarkably compared to Cd only and Pb only treated plants respectively. This may be due to the stress mitigating effect of microbes on the heavy metal stressed plants. This inference is further supported by the results on tolerance index whereby the tolerance index of heavy metal + microbe treated A. ficoidea plants enhanced compared to the heavy metal only treated plants.

The study revealed the stressful conditions exerted by heavy metals and the stress relieving effect provided by microbes on heavy metal stressed A. ficoidea . However, more studies are required to find out the reasons behind these kinds of responses. Moreover, various anatomical, physiological, biochemical and molecular factors associated with the change in the growth parameters, moisture content and tolerance index need to be identified. Additionally, further studies can be conducted to find out an effective microbe for enhancing the Pb accumulation in A. ficoidea .

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge the St. Joseph’s College (Autonomous), Devagiri, Kozhikode, Kerala, India and University of Calicut, Malappuram, Kerala, India for providing the facilities to conduct the research work. APC acknowledges the funding provided by University Grants Commission, New Delhi; through Junior Research Fellowship (K 1216200175) for the research work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.