Enhancing quinoa’s photosynthetic capacity under high NaCl using a fabricated nanocomposite, ZnO/SiO₂/GO

Автор: Enas G. Badran, Nouriya S. Mohammed, Nemat M. Hassan, Mamdouh M. Nemat Alla, Mohamed M. EL-Zahed

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

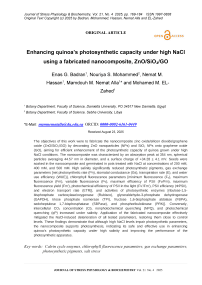

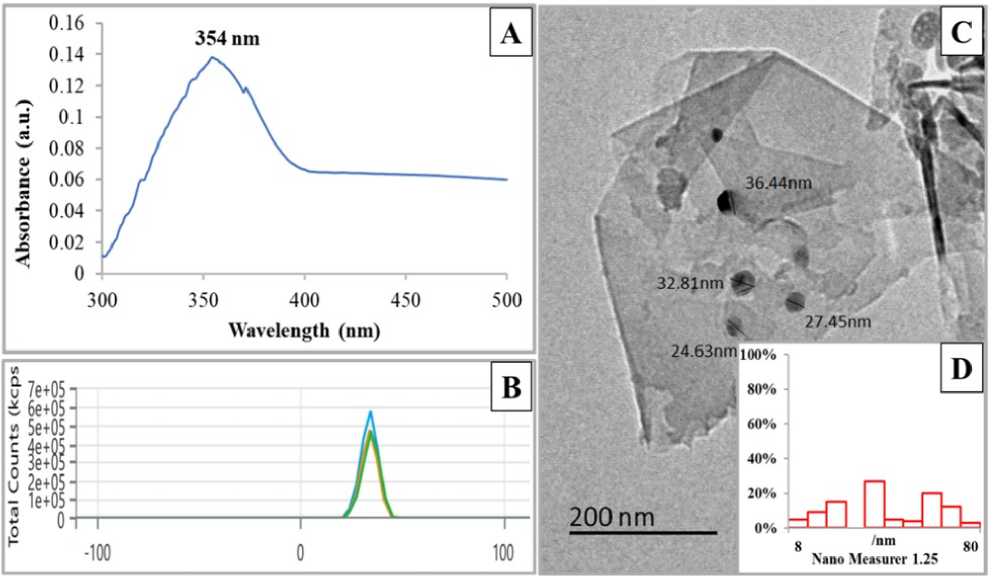

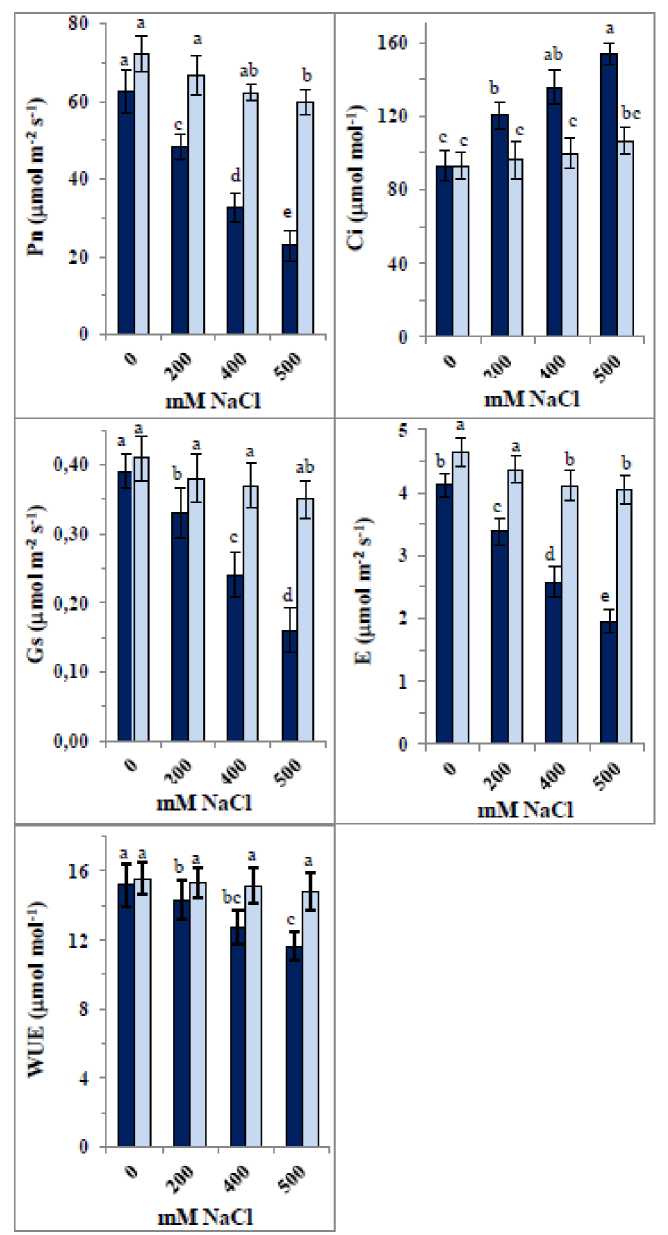

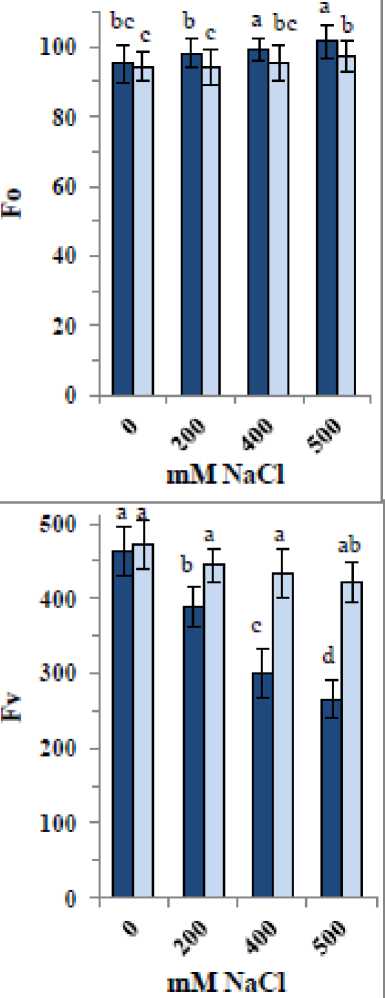

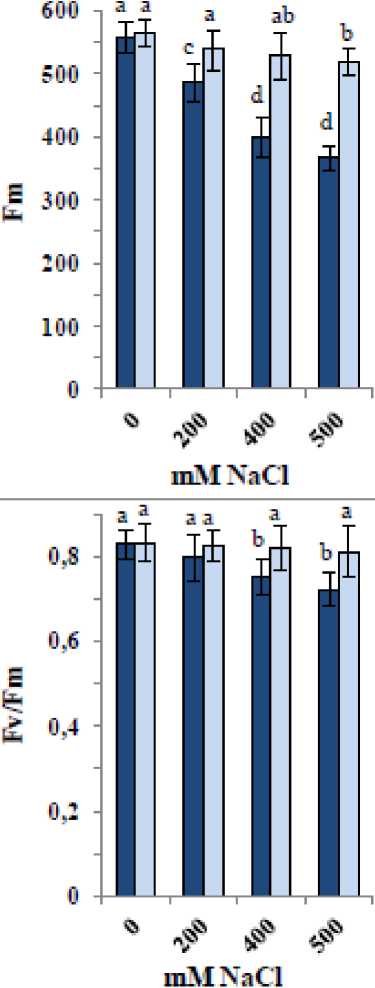

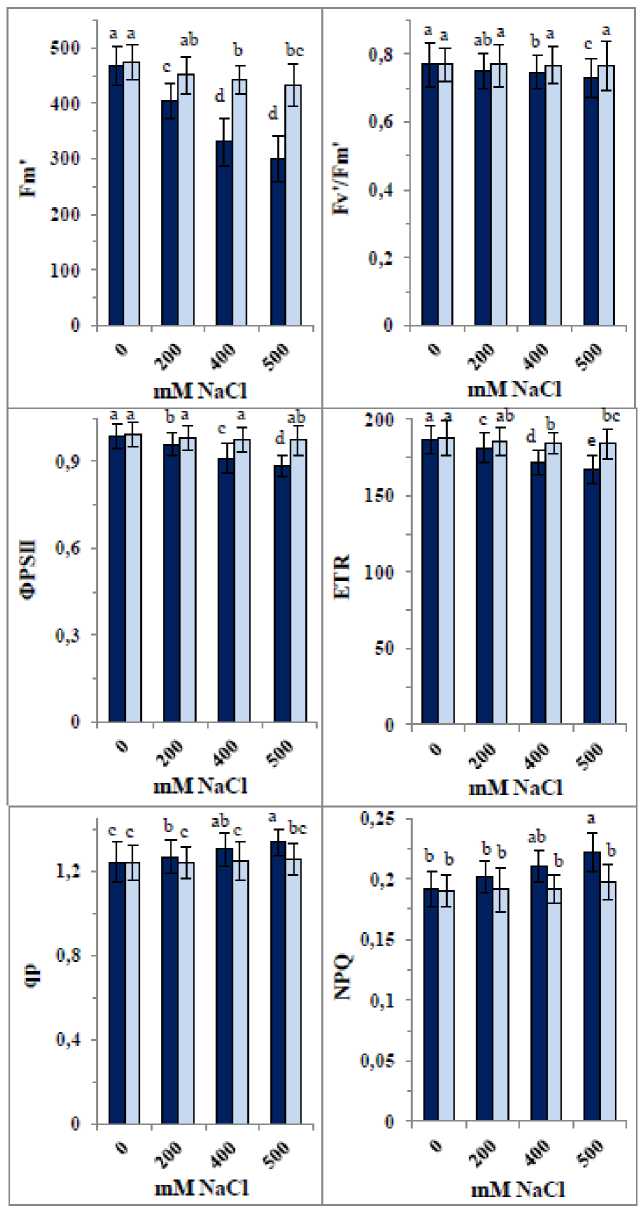

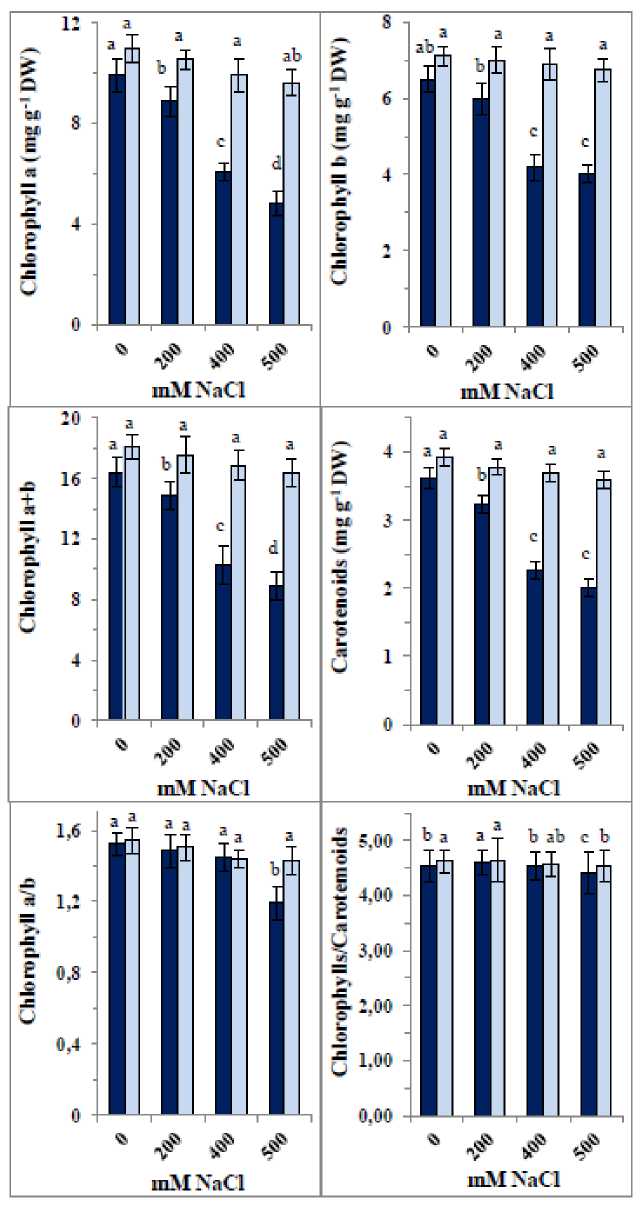

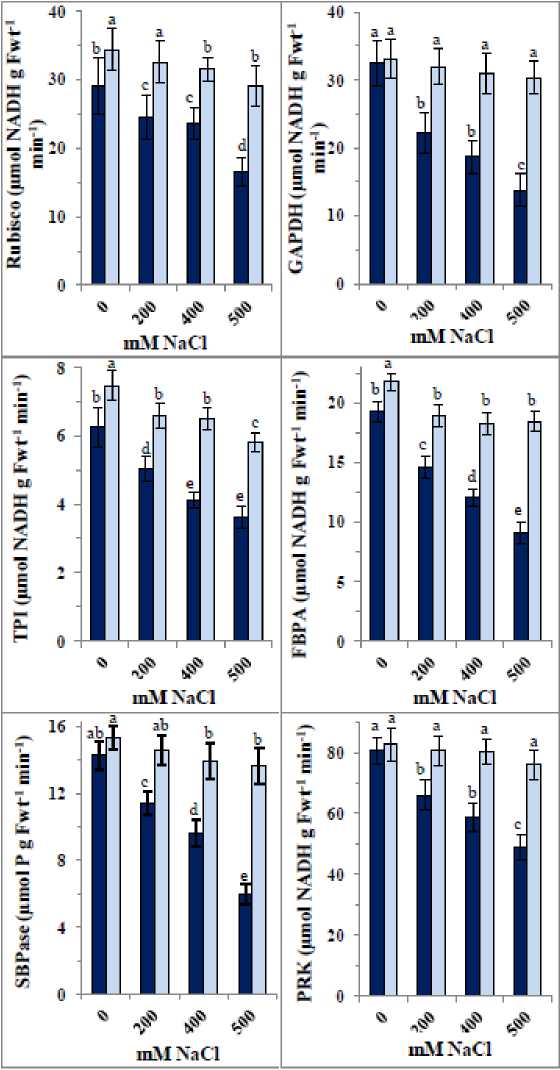

The objectives of this work were to fabricate the nanocomposite zinc oxide/silicon dioxide/graphene oxide (ZnO/SiO₂/GO) by decorating ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) and SiO₂ NPs onto graphene oxide (GO), aiming for efficient enhancement of the photosynthetic capacity of quinoa grown under high NaCl conditions. The nanocomposite was characterized by an absorption peak at 354 nm, spherical particles averaging 44.57 nm in diameter, and a surface charge of +34.28 ± 4.1 mV. Seeds were soaked in the nanocomposite and germinated in pots treated with NaCl at concentrations of 200 mM, 400 mM, and 500 mM. High salinity significantly reduced photosynthetic pigments, gas exchange parameters [net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), transpiration rate (E), and water use efficiency (WUE)], chlorophyll fluorescence parameters [minimum fluorescence (F₀), maximum fluorescence (Fm), variable fluorescence (Fv), maximum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm), maximum fluorescence yield (Fm'), photochemical efficiency of PSII in the light (Fv’/Fm’), PSII efficiency (ΦPSII), and electron transport rate (ETR)], and activities of photosynthetic enzymes [ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), triose phosphate isomerase (TPI), fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (FBPA), sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase), and phosphoribulokinase (PRK)]. Conversely, intercellular CO₂ concentration (Ci), nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ), and photochemical quenching (qP) increased under salinity. Application of the fabricated nanocomposite effectively mitigated the NaCl-induced deterioration of all tested parameters, restoring them close to control levels. These findings demonstrate that although high NaCl levels impair photosynthetic parameters, the nanocomposite supports photosynthesis, indicating its safe and effective use in enhancing quinoa’s photosynthetic capacity under high salinity and improving the performance of the photosynthetic apparatus.

Calvin cycle enzymes, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, gas exchange parameters, photosynthetic pigments, salt stress

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143185133

IDR: 143185133

Текст научной статьи Enhancing quinoa’s photosynthetic capacity under high NaCl using a fabricated nanocomposite, ZnO/SiO₂/GO

Quinoa ( Chenopodium quinoa ) is considered an important alternative crop due to its exceptional nutritional profile, which includes high energy content, substantial protein levels, minerals, vitamins, quality fatty acids, and beneficial secondary metabolites that help regulate blood sugar levels and prevent degenerative diseases (Pereira et al ., 2019; Zahra et al ., 2020). It is one of the most salt-tolerant crops; however, very high salinity levels disrupt several metabolic processes and suppress vital physiological functions. Photosynthesis is among the most affected processes under salinity stress (Stefanov et al ., 2019; Zahra et al ., 2022). educed photosynthesis under salinity is caused not only by stomatal closure, which reduces intercellular CO₂ concentration, but also by non-stomatal factors (Amuthavalli and Sivasankaramoorthy, 2012).

Monitoring changes in photosynthetic activity is an effective method to evaluate plant tolerance to stress (Liu et al., 2024). The net photosynthetic rate (Pn) reflects the overall rate of carbon assimilation, while stomatal conductance (Gs) indicates the rate at which CO₂ enters and water vapor exits through the stomata. Sub-stomatal CO₂ concentration (Ci), influenced by Pn and Gs, refers to the CO₂ available inside the leaf for photosynthesis. Stomatal closure also reduces transpiration (E), helping conserve water. Salt stress significantly reduces gas exchange, decreasing Pn and E in bael ( astogi et al., 2020). Musyimi et al. (2007) reported decreases in Pn, Gs, and E in avocado under salinity. These parameters, along with chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, are strongly affected by salinity. Chlorophyll fluorescence serves as a natural indicator of photosynthetic activity due to the emission of fluorescence quanta (Matorin et al., 2013). Minimum fluorescence (F₀) measures baseline fluorescence when PSII reaction centers are fully open, while maximum fluorescence (Fm) measures fluorescence when all PSII reaction centers are closed. Variable fluorescence (Fv) represents PSII efficiency, and the maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) indicates the maximum efficiency of PSII photochemistry, reflecting plant health. The effective quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) and electron transport rate (ET ) respectively measure the actual efficiency of PSII under light and the rate of electron transfer during photosynthesis. Photochemical and nonphotochemical quenching coefficients (qP and NPQ) regulate energy dissipation. Environmental stresses damage the PSII system, disrupting electron transport and photochemical efficiency (Guidi et al., 2019). Shin et al. (2020) found that chlorophyll fluorescence in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) was significantly affected by NaCl. Plant tolerance is reflected in chlorophyll fluorescence, with tolerant genotypes showing higher Fv/Fm under salinity stress (Dugasa et al., 2019).

Besides, salinity negatively influence photosynthetic pigments. Musyimi et al . (2007) observed reduced chlorophyll in avocado seedlings under salinity. Carotenoids protect chlorophyll from photooxidation by removing oxygen from chlorophyll-oxygen complexes via the carotenoid-epoxide cycle (Nemat Alla et al ., 2008). Additionally, salinity profoundly affects Calvin cycle enzymes, including ubisco, the key enzyme catalyzing the carboxylation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate ( uBP) into 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA) (Nemat Alla et al ., 2020). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) converts 1,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid (1,3-PGA) to GAP, while triose phosphate isomerase (TPI) catalyzes the reversible conversion of GAP and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), which are condensed to form fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) by fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (FBPA). Sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase) removes a phosphate from sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphate to produce sedoheptulose 7-phosphate whereas phosphoribulokinase (P K) regenerates uBP from ribulose 5-phosphate ( uP), the initial substrate of the Calvin cycle. The inhibition of these enzymes would consequently reduce the photosynthetic capacity.

Given the urgent need to increase crop productivity to meet growing food demands, particularly using marginal, saline lands, exogenous supports that improve photosynthetic energy conversion to biomass are vital. Among these supports, nanoparticles (NPs) are promising in mitigating salinity stress (Simkin et al., 2017). Because quinoa is considered a good alternative crop and tolerates relatively high salinity, an attempt was achieved to increase this tolerance to levels not tolerated by other crops (excessive concentrations of up to 400 or 500 mM). A nanocomposite was fabricated, in this study, from ZnO, SiO₂, and GO nanoparticles to enhance quinoa’s tolerance to these high concentrations, enabling it to be grown in highly saline soils unsuitable for other crops, thus increasing the efficiency of the photosynthetic machinery components to provide a greater amount of food. The nanocomposite comprises Zn with its essential roles in plant growth functions (Alsafran et al., 2022), Si which has benefits in stress tolerance and photosynthesis (Liang et al., 2015), and GO with positive effects on chlorophyll content and growth (Safkhan et al., 2018). Thus, the objective was to fabricate a high-performance nanocomposite—zinc oxide/silicon dioxide/graphene oxide (ZnO/SiO₂/GO)— by decorating ZnO and SiO₂ NPs onto GO to enhance quinoa’s photosynthetic apparatus under high salinity stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication of zinc oxide/silicon dioxide/graphene oxide (ZnO/SiO 2 /GO) nanocomposite

ZnO was fabricated by gradual addition of 0.4 M KOH to 0.2 M Zn(NO3)2 while being vigorously stirred followed by centrifugation at 5000 ×g for 15 min, the resulting ZnO NPs were calcined at 500°C for 3 h (Satdev et al., 2020). SiO2 was fabricated by dropwise addition of Na2SiO3 solution to 33% ammonia/absolute ethanol (3:1 v/v) followed by centrifugation at 5000 ×g for 15 min, the SiO2 NPs were dried at 50°C for 24 h followed by additional 5 h at 185°C (Baka and El-Zahed, 2022). GO was fabricated from the oxidation of graphite using H2SO4/HNO3 (3:1 v/v) in ice-water bath with agitation for 3 h at 35°C then distilled water was gradually added while being vigorously stirred (Hummers and Offeman, 1958). After changing the color into dark brown, the reaction mixture was diluted then H2O2 was added dropwise. The resultant GO was adjusted to pH 7 and centrifuged for 15 min then GO was dried at 80°C. Decoration of ZnO NPs and SiO2 NPs was performed onto GO, firstly polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was dissolved in 5 % acetic acid followed by the addition of chitosan (CS) forming CS/PVA then GO was disperssed in CS/PVA thereafter, CS/PVA containing GO was ultrasonicated for an hour at 25°C (El-Zahed et al., 2024). Finally, ZnO NPs and SiO2 NPs were added and stirred for an hour, then glutaraldehyde was added to the stirring suspension. The nanocomposite was characterized using double beam UV–Vis spectrophotometer (V-760, JASCO, UK), Zeta potential Malvern Zetasizer (Nano-ZS90, Malvern, UK), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100, Japan).

Plant material and growth conditions

Certified seeds of quinoa [ Chenopodium quinoa (L.)], obtained from Sakha Agricultural esearch Station, Kafr El-Sheikh, Egypt, were surface sterilized in 1% w/v sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, rinsed with water several times and soaked for 6 h either in water or in the fabricated nanocomposite (ZnO/SiO 2 /GO at 40 mg L-1). This concentration of nanocomposite was selected based on a preliminary experiment in order to determine the optimal concentration effective and beneficial for mitigating the effects of high salinity, without interfering with stress effects. Seeds of both groups were planted in plastic pots (40 × 25 × 15 cm), each contained 3 kg of soil (clay: sand; 2:1 w/w), approximately 2 cm-depth and allowed to grow at 22±2/12±2°C, day/night temperature with a 12-h photoperiod at 420-460 mol m-2 s-1 PPFD. Each pot received 200 ml water daily for 3 days followed by Long Ashton nutrient solution up to the 10th day, then pots of both groups were divided into four subgroups for treatment with NaCl at 0 mM (control), 200 mM, 400 mM and 500 mM; each pot received 200 ml every 3 days for 21 days. When seedlings were 35-day-old, gas exchange parameters and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were monitored in seedlings using the 3rd newest leaf then collected, washed thoroughly with water, plotted dry between layers of tissue, and used for determination of photosynthetic pigments and the photosynthetic enzyme activity assays.

Measurement of gas-exchange parameters

Net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (E) were measured in the fully expanded 3rd leaf in situ after being subjected to light for at least 4 h using a portable photosynthesis meter with leaf chamber area of 2 × 5.5 cm. The conditions were controlled during the measurement, 360 ± 10 μmol mol–1 CO2 concentration, 25 °C temperature, and about 60% relative humidity. The final mean values of Pn, Gs, Ci and E were calculated then, the water-use efficiency (WUE) was calculated as Pn/E.

Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

After dark-adaption, baseline minimal fluorescence (F0) was determined under sufficiently low irradiance and maximum fluorescence yield (Fm) was determined after a saturation pulse at 4200 μmol m-2 s-1 on the dark-adapted leaves, then variable fluorescence (Fv=Fm-F0) and optimal PSII yield [Fv/Fm=(Fm–F0)/Fm] were calculated. In the light-adapted leaves, radiation of the saturation pulses was used to determine the minimum fluorescence yield in the light-adapted state (F0'), the steady-state fluorescence yield (Fs) and the maximal fluorescence (Fm′) then the quantum yield of photosystem PSII photochemistry

[ΦPSII=(Fm'–Fs)/Fm')], the photochemical efficiency of PSII in the light (Fv'/Fm'), the electron transport rate (ET =ΦPSII/PA /LD/AF; PA , photosynthetically active radiation; LD, distribution of light between PSII; PSI, 0.5; AF, absorption factor~0.84), and the photochemical quenching [qP=1–(Fs–F0')/(Fm'–F0')], and nonphotochemical quenching [NPQ=(Fm–Fm')/Fm'] coefficients were calculated.

Measurement of pigment contents

Chlorophylls ( a and b ) and carotenoids were extracted with 80% acetone and then absorbance was read at 663.2, 646.8 and 470 nm (Lichtenthaler, 1987). Pigment contents were calculated as µg ml-1 according the following equations (and then converted to µg g-1): Chlorophyll a (Chla)=12.25A663.2–2.79A646.8, Chlorophyll b (Chlb)=21.50A646.8–5.10A663.2, Carotenoids (Car)=(1000A470-1.82(Chla)-85.02(Chlb))/198.

Enzyme activity assay

Extraction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase ( ubisco) was performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) containing 10 mM MgCl 2 , 1 mM EDTA, 15 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% (w/v)

polyvinylpyrrolidone and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100

(Holaday et al . 1992). The activity was assayed in 50 mM 4-(2-hydroxymethyl)1-piperazine ethane sulfonic acid (Hepes, pH 7.8) containing 10 mM NaHCO 3 , 20 mM MgCl 2 , 0.66 mM ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate ( uBP), 0.2 mM NADPH, 5 mM ATP, 5 mM creatine phosphate, 2 U creatine phosphokinase, 2.8 U glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and 2 U phosphoglycerate kinase then absorbance was measured at 340 nm to measure the oxidation of NADPH (Keys and Parry, 1990). GAPDH was assayed in 13 mM sodium pyrophosphate containing 26 mM sodium arsenate, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 750 μM NAD, and 2.5 mM GAP (pH 7) (Shao et al . 2007). Absorbance at 340 nm was recorded at 10 s intervals for 5 min for measuring the reduction of NAD. Triose phosphate isomerase (TPI) activity was measured in 0.1 M triethanolamine (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM NADH, 50 U ml-1 glycerol-3-P DH, and 1 mM GAP then absorbance was measured at 340 nm for measuring NADH consumption (Benitez-Cardoza et al ., 2001). Fructose 1,6-bisphophate aldolase (FBPA) was extracted in 100 mM Hepes (pH 8.1), 5 mM MgC1 2 , 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis([3-aminoethylether)-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM benzamidine, 2 mM eaminocaproic acid, 0,5 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 5 mM KHCO 3 and centrifuged at 2000 ×g for 2 min (Krapp et al . 1991; Holaday et al . 1992). The activity was assayed in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) containing 5 mM MgCl 2 , 1 mM EDTA, 150 µM NADH, 2 mM FBP, 5 U TPI, 2 U glycerol-3-P DH and absorbance was read at 340 nm to measure the consumption of NADH (Haake et al ., 1998). Sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase) was extracted in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2) containing 10 mM MgCl 2 , 1 mM EDTA and 20 mM DTT. The activity was assayed in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.2) containing 15 mM MgCl 2 , 1.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT and 2 mM SBP (Simkin et al . 2017), incubated for 30 min at 25 °C, then stopped by 1 M perchloric acid, incubated at room temperature for 30 min followed by the addition of Biomol Green and the absorbance was measured at 620 nm to determine the phosphate release (Schimkat et al . 1990). Phosphoribulokinase (P K) was extracted in 0.05 M potassium phosphate pH 6.5) and centrifuged at

20,000 ×g for 30 min. Assay of P K was carried out in 92 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.2) containing 5 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl 2 , 35 mM KCl, 0.2 mM u-5-P, 0.3 mM NADH, 10 U pyruvate kinase, 15 U lactate dehydrogenase to promote the oxidation of NADH with u-5-P phosphorylation, 0.2 mM PEP then absorbance was read at 340 nm to followed NADH oxidation (MacElory et al ., 1972).

Statistical analysis

The experiment was repeated twice and samples were taken in triplicates from both experiments (n=6) from which mean values (± SD) were applied. The experiment was designed as a complete randomized block consisting of 160 pots (2 sets for ZnO/SiO 2 /GO treatments: control, 40 mg L-1) x (4 sets for NaCl treatments: control, 200 mM, 400 mM and 500 mM) x (10 replications) x (2 repetitions). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant differences (LSD) at 5% level were performed.

RESULTS

Figure 1 presents the characterization studies of the fabricated ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite. A characteristic peak at 354 nm appeared in the UV–Vis spectrum, indicating the successful formation of the NPs (Fig. 1A). The substantial surface charge of the nanocomposite was confirmed by zeta potential measurements, which showed a positive charge of +34.28 ± 4.1 mV (Fig. 1B). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of ZnO/SiO₂/GO (Fig. 1C) revealed spherical particles with an average diameter of 44.57 nm, well-distributed on the GO sheets. The nanoparticle size distribution graph showed frequencies of 3% and 5% corresponding to a maximum size of 80.02 nm and a minimum size of 8.9 nm, respectively (Fig. 1D).

As shown in Figure 2, NaCl significantly reduced gas exchange parameters— Pn, Gs, and E —in quinoa seedling leaves, with the effect intensifying at higher NaCl concentrations. The reductions ranged from 23– 64% in Pn, 15–59% in Gs, and 18–53% in E. In contrast, WUE was least affected, with decreases of approximately 6–23%, while Ci significantly increased by approximately 29–66%. Pre-soaking quinoa seeds in the fabricated ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite improved gas exchange parameters in both control and NaCl-treated samples, resulting in approximate increases of 15%, 5%, and 13% in Pn, Gs, and E, respectively, along with a 2% increase in WUE and a reduction in elevated Ci levels.

In salinity-treated seedlings, the nanocomposite significantly counteracted the NaCl-induced reductions in Pn and E at 200 mM NaCl, reversing them to slight increases (7% and 6%, respectively). At 400 mM and 500 mM NaCl, the decreases were limited to no more than 5% and 2%, respectively. Similarly, reductions in Gs at 200 mM, 400 mM, and 500 mM NaCl were minimized to only 3%, 5%, and 10%, respectively, while the elevated Ci was lowered to 4%, 7%, and 15%, respectively, with the nanocomposite also negating the effects of 200 mM and 400 mM NaCl on WUE.

Figure 3 shows that NaCl significantly decreased chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fm, Fv, and Fv/Fm) in quinoa seedlings, with greater decreases observed at higher concentrations. Conversely, F0 increased by approximately 3–6%. The most substantial decline was observed in Fv, followed by Fm and Fv/Fm, with reductions of 16–43%, 13–34%, and 4–13%, respectively. Application of the ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite to control samples caused slight increases of up to 2% in Fm, Fv, and Fv/Fm. Moreover, the nanocomposite largely mitigated the NaCl-induced decreases in Fm, Fv, and Fv/Fm and the increase in F0, bringing these values close to those of the controls. Overall, the greatest reductions in Fm, Fv, and Fv/Fm under salinity did not exceed 9%, and the increase in F0 was less than 2%.

Additionally, 200 mM, 400 mM, and 500 mM NaCl significantly decreased Fm' by about 14%, 29%, and 36%, respectively; however, the nanocomposite reduced these declines to only 4–7% (Fig. 4). NaCl also significantly lowered Fv’/Fm’, ΦPSII, and ET , although these decreases were minor (3–5%). The nanocomposite completely alleviated these reductions. In contrast, all NaCl concentrations elevated NPQ and qP by approximately 6–16% and 2–14%, respectively; these increases were fully reversed by the nanocomposite, restoring values close to control levels.

Figure 5 shows that 400 mM and 500 mM NaCl significantly reduced chlorophyll a and b contents, their total (chlorophyll a+b), and carotenoids. Specifically, 400 mM and 500 mM NaCl caused decreases of approximately 39–51% in chlorophyll a, 36–38% in chlorophyll b, 38–46% in chlorophyll a+b, and 38–45% in carotenoids. Only 50 mM NaCl reduced the chlorophyll a/b ratio by about 22%, while the chlorophyll a+b/carotenoids ratio remained unchanged across all NaCl concentrations. Treatment with the ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite increased chlorophylls and carotenoid contents by approximately 8–11% in control plants, with slight increases in both chlorophyll a/b and carotenoids/chlorophyll a+b ratios. Furthermore, the nanocomposite significantly mitigated the NaCl effects on pigment levels and ratios, restoring them close to control values.

Simultaneously, NaCl significantly inhibited activities of Calvin cycle enzymes: ubisco, GAPDH, TPI, FBPA, SBPase, and P K (Fig. 6). The response pattern was similar across enzymes, with the highest NaCl concentration exerting the strongest inhibition. SBPase, GAPDH, and FBPA activities were more inhibited (20– 58%, 31–58%, and 24–53%, respectively) than ubisco and TPI (16–43% and 20–42%, respectively), while P K showed the least inhibition (18–39%). Application of the ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite enhanced enzyme activities in control samples, with the greatest increases observed in TPI and ubisco (19% and 18%, respectively), moderate increases in FBPA and SBPase (13% and 7%), and smaller increases in GAPDH and P K (2% each). In NaCl-treated samples, the nanocomposite largely alleviated enzyme inhibition, limiting reductions to 7% in GAPDH and TPI, 6% in P K, 4% in FBPA and SBPase, and completely reversing inhibition in ubisco.

Figure 1: Characterization of ZnO/SiO 2 /GO. (A) UV–Vis spectroscopy analysis. (B) Zeta potential analysis. (C) TEM image with scale bar = 200 nm. (D) Nanogravimetric image showing the particle size distribution of the NPs on the GO sheets.

Figure 2: Changes in gas-exchange parameters [Net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), intercellular CO 2 concentration (Ci), transpiration rate (E) and water-use efficiency (WUE)] of 35-day old quinoa subjected to NaCl treatment for the preceding 21 days, after soaking the seeds in 40 mg L-1 of the fabricated nanocomposite ZnO/SiO 2 /GO. Dark-coloured bars, without nanocomposite; light-coloured bars, with nanocomposite. Data are means ± SD of three independent replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

Figure 3: Changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters [baseline minimal fluorescence (F0), maximum fluorescence yield (Fm), variable fluorescence (Fv) and optimal PSII yield [Fv/Fm] of 35-day old quinoa subjected to NaCl treatment for the preceding 21 days, after soaking the seeds in 40 mg L-1 of the fabricated nanocomposite ZnO/SiO 2 /GO. Dark-coloured bars, without nanocomposite; light-coloured bars, with nanocomposite. Data are means ± SD of three independent replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

Figure 4: Changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters [maximum fluorescence yield in the light-adapted state (Fm'), photochemical efficiency of PSII in the light (Fv'/Fm'), quantum yield of photosystem PSII photochemistry (ΦPSII), electron transport rate (ET ), photochemical quenching (qp) and nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ)] of 35-day old quinoa subjected to NaCl treatment for the preceding 21 days, after soaking the seeds in 40 mg L-1 of the fabricated nanocomposite ZnO/SiO 2 /GO. Dark-coloured bars, without nanocomposite; lightcoloured bars, with nanocomposite. Data are means ± SD of three independent replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

Figure 5: Changes in pigment contents in 35-day old quinoa subjected to NaCl treatment for the preceding 21 days, after soaking the seeds in 40 mg L-1 of the fabricated nanocomposite ZnO/SiO 2 /GO. Dark-coloured bars, without nanocomposite; light-coloured bars, with nanocomposite. Data are means ± SD of three independent replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

Figure 6: Changes in the photosynthetic enzyme activities [ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase ( ubisco), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), triose phosphate isomerase (TPI), fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (FBPA), sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase), and phosphoribulokinase (P K)] of 35-day old quinoa subjected to NaCl treatment for the preceding 21 days, after soaking the seeds in 40 mg L-1 of the fabricated nanocomposite ZnO/SiO 2 /GO. Dark-coloured bars, without nanocomposite; lightcoloured bars, with nanocomposite. Data are means ± SD of three independent replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

DISCUSSION

Quinoa’s exceptional nutritional profile, combined with its higher tolerance to salinity compared to other cereals, makes it a promising crop for cultivation in saline and marginal soils to help increase food productivity and close the food gap. Despite its increased salinity tolerance, quinoa remains vulnerable to the damaging effects of high salt concentrations. To withstand such harsh conditions and maximize tolerance, external aids are needed to mitigate abiotic stresses (Dilnawaz et al., 2023).

A nanocomposite was fabricated herein by decorating ZnO and SiO₂ NPs onto GO sheets to serve as an external support for alleviating the impacts of high salinity. The absorption peak at 354 nm closely matched those reported by Saleem et al . (2022) and Fayed et al . (2025). Zeta potential analysis indicated strong repulsive forces between particles, which likely prevented NP agglomeration and aggregation. TEM images confirmed the successful synthesis of spherical ZnO/SiO₂ NPs well-decorated on the GO surface, with an average diameter of 44.57 nm, a maximum size of 80.02 nm (frequency = 3%), and a minimum size of 8.9 nm (frequency = 5%) were detected as indicated by nanoparticle size distribution graphs.

This fabricated nanocomposite showed clear potential as an anti-salinity agent. High NaCl concentrations (400 mM and 500 mM) significantly reduced Pn, Gs, and E, with a lesser effect on WUE, while increasing Ci. The reduction in photosynthetic capacity is likely due to inhibition of photosynthetic enzymes and impairment of the photosynthetic apparatus (Safdar et al., 2019; Nemat Alla et al., 2020). Decreased Gs under salt stress reduces CO₂ availability, leading to declines in Pn. High salinity induces osmotic stress, causing stomatal closure to limit water loss. Zhang et al. (2022) reported that photosynthesis reduction under salinity results from decreased Gs, disrupted metabolism, and/or inhibited photosynthetic capacity. These findings align with Musyimi et al. (2007), who observed declines in Pn, Gs, E, and chlorophyll content in avocado seedlings exposed to salinity. The observed decrease in Gs explains the reductions in Pn and E. Conversely, decreased Gs coupled with increased Ci may represent an adaptive response to extracellular CO₂, adjusting diffusion limitations relative to mesophyll demand for CO₂. astogi et al. (2020) reported significant reductions in gas exchange parameters under salt stress in bael. Salinity alters other photosynthetic components such as enzymes, chlorophylls, and carotenoids (Desingh and Kanagaraj, 2020). The application of ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite positively influenced photosynthetic gas exchange in NaCl-treated seedlings, mitigating decreases in Pn, Gs, E, and WUE and alleviating increases in Ci. Ci is influenced by Gs and Pn, and may decrease with faster CO₂ assimilation. In this connection, Torres et al. (2022) indicated that NPs have shown potential in enhancing photosynthesis under stress. The nanocomposite’s positive effect on Gs likely results from improved stomatal opening and enhanced CO₂ uptake, which in turn increases Pn. Enhanced Pn may also arise from improved light absorption, electron transport, and stress tolerance. Changes in Gs directly affect Ci, and improved WUE results from optimized Gs reducing water loss while maintaining CO₂ uptake. NPs stimulate photosynthesis by promoting chlorophyll synthesis, enzyme activities, regulating stomatal dynamics enhanceing light absorption and energy conversion, improving electron transport in photosystems, increasing ATP and NADPH availability for carbon fixation, CO₂ assimilation, and OS scavenging, thus preventing declines in Pn under stress (Tripathi et al., 2015; Bharti et al., 2018; izwan et al., 2019). Together, the nanocomposite components make it highly effective in enhancing quinoa’s photosynthetic machinery to tolerate high salinity by optimizing stomatal opening, allowing greater CO₂ influx, ensuring efficient gas exchange without excessive water loss, facilitating electron transfer, and improving Pn.

A useful indicator of photosynthetic capacity and plant health is the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Murchie and Lawson, 2013). Minimum and maximum fluorescence (F₀ and Fₘ), Fᵥ, NPQ, qP, ΦPSII, and ET were monitored. Salinity reduced Fₘ, Fᵥ, and Fᵥ/Fₘ, indicating decreased photochemical efficiency and increased energy dissipation, which aligned with declines in chlorophyll content, Gs, and E, leading to reduced Pn as indicated by Hosseini et al. (2023) in Mentha spp. Salinity-induced damage to PSII disrupts the electron transport chain, as shown by decreases in Fᵥ/Fₘ due to photodamage and quenching loss (Guidi et al., 2019; Hosseini et al., 2023). The decreases in fluorescence parameters observed herein concomitant with reductions in gas exchange and pigments, highlighting salinity’s impact on quinoa tolerance. Dugasa et al. (2019) noted that tolerant genotypes maintain higher Fᵥ/Fₘ under salinity stress. The nanocomposite application improved quinoa’s tolerance by restoring F₀, Fₘ', and Fᵥ/Fₘ under NaCl stress and increasing ET and ΦPSII, enhancing overall photosynthesis while reducing NPQ to allow more energy for photochemistry. This beneficial effect was also evident in improved gas exchange and pigment content. The role of carotenoids in the protection of chlorophyll from photooxidation via the carotenoid-epoxide cycle is also influenced by stress (Nemat Alla et al., 2008; 2020), so decreases in carotenoids herein likely reduced chlorophyll protection, negatively impacting photosynthetic capacity. Since chlorophyll and carotenoid ratios remained consistent regardless of salinity level, both pigments are likely equally affected. ZnO, SiO₂, and GO each contribute to enhanced tolerance due to the essential role of Zn for enzymatic functions and ion homeostasis (Alsafran et al., 2022), the importance of Si in improving stress tolerance and photosynthesis (Liang et al., 2015), and the benefits of GO in chlorophyll stability (Safkhan et al., 2018).

Not only the light-dependent phase is influenced by salinity but also the dark phase of photosynthesis involving carbon fixation by the Calvin cycle enzymes that utilize ATP and NADPH produced during the light phase. Salt stress disrupts Calvin cycle enzymes by interfering with their structure and function, and reduced CO₂ availability from stomatal closure limits the ubisco substrate. Desingh and Kanagaraj (2020) reported decreases in Pn and ubisco activity with increasing salinity in sesame Sesamum indicum L.). Salinity also reduces GAPDH activity due to NADPH imbalance from impaired electron transport. FBPA and SBPase are downregulated under high salinity, negatively affecting carbon assimilation and photosynthetic efficiency (Simkin et al., 2017). P K, a key Calvin cycle enzyme regenerating uBP via ATP-dependent phosphorylation, declines under salt stress due to limited ATP availability, compounding CO₂ fixation reduction concluding that Calvin cycle enzyme activities improve energy conversion efficiency and yield potential (Zhu et al., 2010; Uematsu et al., 2012). The activities of these enzymes were enhanced by ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite through boosting light absorption and energy production, thereby improving carbon fixation efficiency. It modulated chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, improved light reactions and enhanced ubisco efficiency and other enzymes for dark reactions. Increased quantum efficiency of PSII and improved Gs allow greater CO₂ influx, enhancing ubisco activity and carbon fixation. Consistent with Simkin et al. (2017), upregulation of SBPase and FBPA increased PSII efficiency, suggesting that boosting individual Calvin cycle enzymes improves photosynthetic carbon fixation. The nanocomposite likely stabilized enzyme conformation or acted as cofactors in catalytic reactions. Furthermore, by enhancing ATP and NADPH availability, it protects Calvin cycle enzymes from oxidative degradation and promotes pigment synthesis, collectively boosting photosynthetic capacity and stabilizing the carbon fixation environment.

CONCLUSIONS

This study successfully fabricated a ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite composed of spherical NPs averaging 44.57 nm in diameter. High NaCl concentrations significantly impaired quinoa’s photosynthetic machinery by reducing gas exchange parameters (Pn, Gs, E, WUE), chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fm, Fv, Fv/Fm, Fm', Fv'/Fm', ΦPSII, ET ), photosynthetic pigments, and Calvin cycle enzyme activities ( ubisco, GAPDH, TPI, FBPA, SBPase, P K), while increasing Ci, NPQ, and qP. Seed presoaking with the ZnO/SiO₂/GO nanocomposite (40 mg L ⁻ ¹ for 6 hours) effectively mitigated the harmful effects of salinity by improving gas exchange, restoring chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, enhancing pigment content, and elevating enzyme activities, maintaining these near control levels under salt stress. These findings suggest that this nanocomposite is a promising agent to boost quinoa’s photosynthetic performance and resilience under high salinity conditions.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interest.