Environmental investment as a key factor in the formation and evolvement of an investment model for the growth of the Russian economy

Автор: Kormishkina Lyudmila A., Kormishkin Evgenii D., Ivanova Irina A., Koloskov Dmitrii A.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Environmental economics

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.15, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The complex debate in the recent economic literature about environmental quality in economic growth, looking for a return to long-term sustainable growth in total factor productivity, recognizing the environmental aspect of development as an imperative confirm the relevance of the research topic. The aim of the study is to provide a theoretical substantiation of environmental investment as a key factor in ensuring long-term and sustainable economic growth, an “active start” to the radical transformation of the Russian economy in accordance with the requirements of the global Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance agenda; another aim is to conduct an experimental testing of the identified scientific idea. Environmental investment is characterized as a type of responsible and transformative investment capable of generating incremental total factor productivity growth by stimulating specific green innovations. The methodology of the study included methods of identification, analysis and verification of an econometric model in the form of a system of dynamic regressions by Sh. Almon with distributed lags. Experimentally (by constructing different regressions and testing Student’s hypotheses for them, determining estimates of t-statistics) as applied to the Russian economy, we evaluated long-term and short-term responses of economic growth indicators to the volume of environmental investment (specifically, its priority focus, such as waste-free and recycling resources). The econometric model has established a long-term positive effect of environmental investments. The effect consists in protecting the integrity of natural capital and improving the condition of ecosystems, which is fundamental to maintaining the potential for economic the long-term growth. Short- and medium-term effects include creating new high-tech jobs in low CO2 sectors and restoring total factor productivity growth through green technological innovation. The main barriers to environmental investment in Russia have been identified, and the minimum necessary economic instruments to stimulate it have been developed.

Economic growth, environmental challenges, global esg agenda, environmental investment, disinvestment, total factor productivity, long-term sustainable economic growth, green economy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147238473

IDR: 147238473 | УДК: 330.322:574(470+571) | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2022.4.82.8

Текст научной статьи Environmental investment as a key factor in the formation and evolvement of an investment model for the growth of the Russian economy

The scale of the shocks taking place in the world economy (including the Russian economy) gives reason to consider the current economic situation as a kind of global cataclysm comparable to the Great Economic Depression or even exceeding it. Quarantine measures applied by most countries (Russia as well) have reduced the mortality rate from COVID-19, but have caused a serious economic recession, which is exacerbated by unprecedented external sanctions pressure on Russia. Against this background, all the problems and limitations of development that have accumulated in the global and national economy in recent decades are becoming more acute. Undoubtedly, the priority among the current trends and patterns belongs to environmental issues.

We should note that the current crisis, for example, for Russia can be reflected by such indicators as a drop in demand for Russian exports, the vast majority (about 90%) of which are raw materials and semi-raw materials, a drop in production due to inflation and a decrease in investment activity. It is obvious that in such conditions, not only the Russian Federation, but also all the economies of the world – poor, rich and medium-developed – are programmed for economic growth in the coming decades. Michael Spence, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics said that “growth is, first of all, a means to an end; it increases people’s chances of productive and creative employment, ... creates freedom and the possibility of self-realization” (Spence, 2012). RAS Corresponding Member R. Grinberg emphasizes that “the prospects of the socio-economic image of the country must be assessed primarily from the viewpoint of the prospects for economic growth” (Grinberg, 2008). In other words, “while the economy is growing, positive feedback mechanisms tend to push the system in the direction of further development” (Jackson, 2009).

In this context, we note that in accordance with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2016–2030, which are a kind of call to action emanating from all nations, annual GDP growth per capita (the most adequate indicator of welfare growth today) is set for the least developed economies at 7% (the goal is 8%); The Supreme Eurasian Economic Council has identified this indicator at 5–5.5% as a benchmark for the EAEU member states. According to the estimates of RAS Academician Sergei Yu. Glazyev, even under the conditions of external sanctions pressure on Russia, a “good and workable” model of the national economy, not rentbased, but oriented toward constant technological modernization as its integrated and organic component, can ensure annual economic growth of at least 10%1 (Glazyev, 2018).

In addition, we should recognize that the growth of the economy in its neoliberal model (in Russia, it is oriented toward raw materials exports), in which its main locomotive is gross consumption, leads to an increased burden on the environment under the influence of an increase in the ecological footprint and ecological debt of mankind, deterioration of environmental quality (saturation of the atmosphere with greenhouse gases and climate change, increasing the volume of harmful waste and emissions, reducing biodiversity and freshwater reserves, soil degradation, depletion of mineral resources, etc.). The identified environmental challenges, which have become global in the 21st century, dictate the need to change the economic paradigm: “The transition to an economic structure that functions not in spite of the productive forces of nature, but with them” (Fucks, 2019), provided by radical transformations of the economy in accordance with the global ESG agenda (Bobylev, 2020; Bobylev et al., 2021; Matveeva, Gridnev, 2022). Moreover, even in the context of the pandemic, the ecological and economic priorities in the development of countries were emphasized at the World Economic Forum held in Davos in 2020. In the forum’s reports, only environmental risks were identified among the traditional priority risks (extreme weather events, failure of climate action, loss of biodiversity, depletion of natural resources, sharp increase in the amount of waste, natural disasters of anthropogenic origin)2.

In the current conditions, when unprecedented external sanctions pressure actually coincided with the exhaustion of the possibilities of the country’s raw-materials-exporting (consumer, rental) model of economic growth, we cannot but recognize that the Russian economy is at a bifurcation point of its development and in a state of unstable equilibrium, when there are several main development options that continue this unstable trend. National projects adopted in accordance with Presidential Decree 204, dated May 7, 2018, including the “Ecology” project, the plan of priority actions for the RF Government for post-crisis economic recovery under external sanctions pressure (approved March 15, 2022), are certainly necessary and capable of supporting the development of the domestic economy. At the same time, from a strategic perspective, they are not enough to ensure GDP growth rates that are ahead of global dynamics. The current situation forces us to look for ways to form a new model of economic growth that can develop and provide a high level of income at the expense of knowledge-intensive, high-tech and resource-efficient production, rather than natural and opportunistic rents.

In other words, we are talking about a model of economic growth that should be adequate to the principles of the global Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance agenda (ESG agenda) and have the following important features:

-

• priority in development is given to knowledge-intensive and high-tech manufacturing and infrastructural types of economic activity with minimal impact on the environment;

-

• environmentally efficient interactions of production and consumption, reducing environmental pollution;

-

• waste-free and resource recycling;

-

• ensuring environmental safety as a special social good, etc. (Fishman et al., 2019; Bobylev et al., 2021).

Against this background, in the framework of tough discussions unfolding in recent economic literature concerning the quality of the environment in the context of economic growth, the increasing number of scientists and experts point out that the possibility of achieving sustainable growth of total factor productivity (TFP) ensuring economic growth (Gordon, 2016) is associated with the change in the balance between consumption and investment in the economy in favor of the latter3 (Spence 2012; Sukharev, 2019, Sukharev, Voronchikhina, 2020; Banerjee, Duflo, 2019), specifically, with “significant advance environmental investments” (Jackson, 2009; Jackson, 2017; Yakovlev et al., 2017; Kormishkina et al., 2018; Spiridonova, 2020; Kormishkina et al., 2021), “which create the right environment for such a flourishing innovation and such a transformation of the environment that we cannot even imagine”4.

To date, environmental investments remain poorly studied and do not have a generally accepted and clear definition, they are often identified with “green” financing and “green” investments. At the same time, relying on the interpretation of the “green” economy by UNEP and on numerous competing goals of environmental investment (reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, productive use of natural capital, replacement of non-renewable natural resources with renewable ones, adaptation and improvement of ecosystems, creation of public assets, etc.), this definition, in our opinion, should be considered as all types of property and intellectual investments in economic activity that not only provide investors with profit, but also help them to achieve a certain environmental benefit in the form of reducing the negative impact on the natural environment and positive social change in the context of sustainable development of economic systems. World practice shows a great return on such investments: their effect (averted damage) in the economy as a whole is 10–15 times higher than their initial volumes (Rakov, 2017; Spiridonova, 2020).

We should add that Russia can benefit from focusing on environmental investment due to the following reasons: 1) ignoring their increasing role due to the preservation of the raw-materialsexporting (rent) model of economic growth promotes anti-sustainable environmental trends (high level of environmental intensity and intensity of pollution; depletion of natural capital; structural shifts in the economy that increase the share of nature-exploiting and polluting economic activities; type of export based mainly on commodities, etc.) that, in turn, jeopardize the achieved economic and social results;

-

2) the economic costs of environmental degradation, which in Russia, according to World Bank experts, range from 1 to 6% of GDP (which significantly exceeds the value of this indicator for developed countries5), reduce the competitiveness of Russia’s economy at the global level; 3) such investments can increase employment in economic sectors with a low carbon footprint, reduce poverty and improve the standard of living and quality of life, and people’s life potential (Banerjee, Duflo, 2019); 4) in the current situation, there is no need to choose between economic growth and environmental protection; these two goals can be achieved simultaneously. The economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and external sanctions pressure provides Russia with a unique opportunity to invest in radical transformations of the 21st century economy in order to make a decisive turn from the sidelines to the highway of socio-economic progress ensured by the formation of a “green” economy.

Such an approach to the nature of environmental investment forms a clear understanding: it is wrong to harm the environment with economic activity, as well as it is wrong to receive income from an environmental disaster. This means that environmental investments simultaneously generate de-investments, that is, withdrawal of funds or their transfer to other, environmentally friendly industries; refusal to invest in securities and funds if they carry out unethical or morally questionable activities from the perspective of the global ESG agenda (Animitsa et al., 2020). Finally, in the context of ensuring longterm sustainable growth of TFP, environmental investments are in line with the criteria and driving forces of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Schwab, 2017) and the non-industrial paradigm of modern development in Russia, the fundamental program of which was justified even before the pandemic economic recession by Russian economic scientists (Gubanov, 2012; Daskovsky, Kiselyov, 2016).

What we have stated above makes it necessary to form the subject area of environmental investment, requires a detailed study of its components. The purpose of our research is to theoretically substantiate and experimentally test the original scientific hypothesis that in the current difficult situation formed in Russia under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and unprecedented external sanctions pressure, first of all, environmental investment can create a “window of opportunity” to launch an effective investment model of economic growth adequate to the requirements of the global ESG agenda; moreover, environmental investment can become an “active start”6 of radical transformations in the 21st century economy.

Research methodology

The methodological basis of our study, besides traditional generally accepted methods of cognition (scientific abstraction, analysis and synthesis, a combination of logical and historical methods, analogy method, etc.), includes econometric methods and models, the specifics of which take into account, among other things, the time lag of endogenous and exogenous indicators. At the same time, designing an estimated econometric model reflecting the long-term and short-term responses of economic growth indicators from the volume of environmental investments is based on a conceptual approach consisting in a combination in one form or another of the components of aggregate demand from the well-known Keynesian macroeconomic model7 with a modified Cobb–Douglas production function, which in addition to traditional components includes the factor such as the formation and processing of production and consumption waste (Pittel et al., 2010). The significance of this factor has increased much due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its limitations.

The indicator “investments in fixed assets aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources”8 is considered as an indicator of environmental investments (according to Rosstat Order 682 “On approval of methodological guidelines for calculating the index of the physical volume of environmental expenditures”, dated November 21, 2018); for other countries of the world, such an indicator is bubble environmental expenditures and business “green” investments9.

Verification of the hypothesis indicated above was carried out using the constructed system of two dynamic regressions by S. Almon (The Almon Polynomial Distributed Lag) (Griffiths et al., 1993) with distributed lags (1):

f ^ it = 8 + P oXit + piXit-i + p2Xit-2 +-----+ P iXit-i + £ t

] ln(y 2t ) = oc + y o ln(Y it ) + y i ln(Y it-i ) + y 2 ln(y it-2 ) +

I +-----И yi ln(K it-i ) + U t , (1)

where Y 2 t is the volume of GDP per capita in the Russian Federation (an indicator of economic growth);

-

Y 1 t is the volume of investments in fixed assets aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources in the RF;

Xt is the volume of formation and processing of production and consumption waste.

Methods of correlation, linear and nonlinear regression, factor and variance analysis, generalized least squares method, as well as the method of instrumental variables were used to identify, analyze and verify the econometric model (1) and its economic interpretation.

In the model (1), β 0, γ 0 are short-term multipliers, ∑l k=1 β k ; ∑l k=1 γ k are long-term multipliers characterizing the change in performance indicators under the influence of a single change in exogenous variables in each of the future time periods under consideration.

According to Almon’s approach, if the effective indicator depends on the current and lag values of exogenous indicators, then the weights βj, γi in (1) comply with the polynomial distribution (2) (Ivanova et al., 2021):

P j = C o + C 1 J + C2P + - + C k Jk ,

Y t = d0 + d 1 i + d2i2 + - + dkik . (2)

The procedure for applying Almon’s method for estimating the parameters of models with a distributed lag (1) assumes:

-

– determining the maximum lag value l;

– determining the degree of the polynomial k describing the lag structure (2);

– introducing instrumental variables (3):

Zo = Xt + Xt _ t + X t-2 + Xt -s +••• + Xt _i ;

Z 1 = Xt-1 + 2Xt-2 + 3Xt-3 +••• + l • Xt-l ;

Z2 = X t-1 + 4X t-2 + 9X t-3 +••• + I2 • X t-i ;

Zk = X t-1 + + 2k Xt-2 + 3k Xt-3 +"‘ lk " Xt-l ; (3)

– determining the parameters of the multiple linear regression (4):

Yt = 8 + C o • Z o + C1 • Z 1 + c2 • Z2 +••• + +ck • Zk + s t , (4)

– using the ratios (5), the parameters of the initial models with a distributed lag (1) are calculated:

P o = C o

P 1 = C o + C 1 + C 2 + C 3 +••• +Ck

P 2 = C o + 2C 1 + 4c 2 + 8C 3 +••• 2kCk

P i = C o + I ■ C i + I2 ■ C 2 + I2 ■ C 3 + ••• + lk ■ ck. (5)

The indicated methodological approach, in our opinion, makes it possible to assess the contribution of different types of environmental investments within their structure not only to aggregate demand, but also to the production potential of the economy, ensuring long-term sustainable economic growth.

Research results

Trends and problems of environmental investment, responsible in its essence and transformative in its functional role

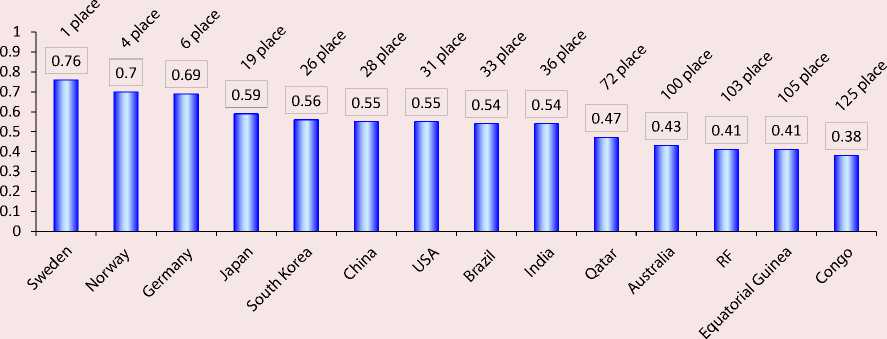

According to the results of the study, even the largest economies of the world show unstable progress in the field of policy and investment that ensure the formation of a new model of the national economy – the “green” economy. This conclusion is clearly confirmed by the values of the Global Green Economy Index (GGEI), developed by the American consulting company Dual Citizen and first calculated in 2010 (in Russia in 2016). According to the results of the 2018 GGEI calculation conducted in 130 countries across four dimensions (leadership and climate change, efficiency sectors, markets and investment, and the environment), among five of the world’s largest economies, Germany shows the strongest performance in the overall index (ranked 6th; GCEI = 0.69), followed by Japan (19th; GCEI = 0.59), China (28th; GCEI = 0.55), the United States (31st; GCEI = 0.55), and India (36th; GCEI = 0.54); Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that Russia ranked only 103rd

Figure 1. Global Green Economy Index, 2018

Source: Dual Citizen official website. Available at: (accessed: April 4, 2022).

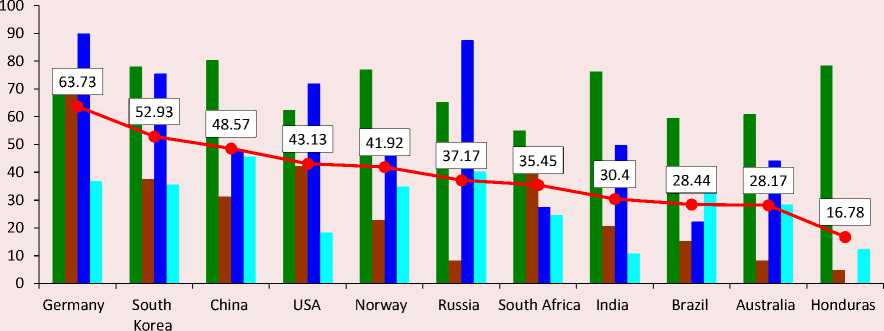

Figure 2. Green economic opportunities of some countries, 2020

^^ "Green" investment

^^ "Green" employment

• "Green" economic opportunities

^^ "Green" trade

^^ "Green" innovation

Source: GGGI Technical Report. 2020. No. 16 (accessed: April 4, 2022).

(GGEI = 0.41), despite its ranking 6th according to the Green Economic Opportunities indicator, the value of which was 37.17%.

For comparison: the GEO value for Germany was 63.73, for China – 48.57 (Fig. 2) .

The need for radical economic transformations in the 21st century and the recognition of the environmental aspect of economic activity as imperative is indicated, among other things, by the fact that most countries show such a negative trend as the increasing ecological footprint of humanity and/or the growing shortage of bio-capacity (our environmental assets). A visual representation of the 2008–2018 dynamics of these indicators in some industrialized countries that to a greater or lesser extent supported the UNDP Green New Deal can be obtained on the basis of the data in Table 1.

Table 1. Dynamics of the ecological footprint and the shortage (surplus) of biocapacity per person in 2008–2018, global hectares

|

Country |

Indicator |

Year |

||||||||||

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

||

|

China |

Biocapacity per person |

0.88 |

0.88 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.91 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.93 |

0.92 |

0.92 |

0.92 |

|

Ecological footprint per person |

2.81 |

3.05 |

3.22 |

3.39 |

3.45 |

3.56 |

3.53 |

3.51 |

3.45 |

3.62 |

3.8 |

|

|

Biocapacity reserve/shortage |

-1.93 |

-2.17 |

-2.32 |

-2.49 |

-2.54 |

-2.66 |

-2.63 |

-2.58 |

-2.53 |

-2.7 |

-2.88 |

|

|

South Korea |

Biocapacity per person |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.68 |

0.67 |

0.65 |

0.66 |

0.66 |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.64 |

|

Ecological footprint per person |

5.7 |

5.42 |

5.86 |

5.9 |

5.76 |

5.73 |

5.64 |

5.77 |

5.88 |

6.17 |

6.32 |

|

|

Biocapacity reserve/shortage |

-5 |

-4.72 |

-5.18 |

-5.23 |

-5.11 |

-5.07 |

-4.98 |

-5.12 |

-5.23 |

-5.52 |

-5.68 |

|

|

Germany |

Biocapacity per person |

1.8 |

1.82 |

1.76 |

1.65 |

1.7 |

1.72 |

1.78 |

1.7 |

1.63 |

1.6 |

1.49 |

|

Ecological footprint per person |

5.57 |

5.15 |

5.55 |

5.42 |

5.22 |

5.24 |

5.06 |

4.95 |

4.83 |

4.81 |

4.67 |

|

|

Biocapacity reserve/shortage |

-3.77 |

-3.33 |

-3.79 |

-3.77 |

-3.52 |

-3.52 |

-3.28 |

-3.25 |

-3.2 |

-3.21 |

-3.18 |

|

|

USA |

Biocapacity per person |

3.6 |

3.63 |

3.56 |

3.43 |

3.4 |

3.45 |

3.47 |

3.44 |

3.54 |

3.4 |

3.39 |

|

Ecological footprint per person |

9.26 |

8.46 |

8.79 |

8.34 |

7.95 |

8.18 |

8.11 |

7.96 |

8.06 |

7.97 |

8.12 |

|

|

Biocapacity reserve/shortage |

-5.66 |

-4.83 |

-5.23 |

-4.91 |

-4.55 |

-4.73 |

-4.64 |

-4.52 |

-4.52 |

-4.57 |

-4.73 |

|

|

Norway |

Biocapacity per person |

8.01 |

7.82 |

7.77 |

7.58 |

7.45 |

7.32 |

7.29 |

7.23 |

7.16 |

7.08 |

6.91 |

|

Ecological footprint per person |

6.94 |

6.13 |

7.15 |

6.36 |

6.17 |

6.42 |

6.12 |

5.8 |

5.44 |

5.73 |

5.67 |

|

|

Biocapacity reserve/shortage |

1.07 |

1.69 |

0.62 |

1.22 |

1.28 |

0.9 |

1.17 |

1.43 |

1.72 |

1.35 |

1.24 |

|

|

RF |

Biocapacity per person |

6.86 |

6.77 |

6.49 |

6.75 |

6.5 |

6.62 |

6.68 |

6.66 |

6.75 |

6.83 |

6.72 |

|

Ecological footprint per person |

5.57 |

5.08 |

5.28 |

5.79 |

5.48 |

5.56 |

5.41 |

5.08 |

5.07 |

5.27 |

5.31 |

|

|

Biocapacity reserve/shortage |

1.29 |

1.69 |

1.21 |

0.96 |

1.02 |

1.06 |

1.27 |

1.58 |

1.68 |

1.56 |

1.41 |

|

Compiled according to: Data Sources: National Footprint and Biocapacity Accounts 2022 edition (Data Year 2018); GDP, World Development Indicators, The World Bank 2020; Population, U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

In the Russian Federation, despite its autonomous economic recession of 2013–2017, there was an increase in the ecological footprint and a reduction in biocapacity per person. And although the country’s “green” environmental opportunities (Fig. 2) allow it to maintain a surplus of biocapacity for the time being, the resource and environmental limitations of the raw-materials exporting model of growth are becoming more and more apparent.

In general, at present there is a situation that requires a new solution to the urgent problem of restoring long-term sustainable growth of TFP in line with the global ESG agenda. This growth should be generated by ecological (“green”) innovations – new technologies, production processes, supply chains that help to solve the issues of waste processing and industrial reproduction of raw materials from waste resources, as well as the use of alternative energy sources (Banerjee, Duflo, 2019). The solution of this super-global task, which has not yet been fully realized by society, requires advance large-scale environmental investments – “the sacrifice that is being made now for the sake of future benefits”10 (Spence, 2012).

Based on the above, we think it is possible to consider environmental investments as a specific type of economic resources (monetary, material and intellectual investments) that can be directed to:

-

• increasing the efficiency of resource use, leading to their savings (for example, energy efficiency and energy conservation, waste reduction and recycling);

-

• replacing traditional technology with environmentally friendly or low-carbon technology operating in accordance with the principles of a closed resource cycle (for example, renewable energy sources; fundamentally new, breakthrough

technologies that exclude the appearance of waste, industrial reproduction of raw materials from waste);

-

• improving the state of ecosystems and improving the quality of the environment (climate adaptation, forest planting, wetlands renewal, etc.) (Kormishkina et al., 2021).

In this sense, environmental investment is consistent with the well-known 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the period from 2016 to 2030 for all countries11, which were formulated in the UN conceptual documents and approved at the UN Conference in 2015:

-

1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

-

2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.

-

3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

-

4. Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

-

5. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

-

6. Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

-

7. Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.

-

8. Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

-

9. Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation.

-

10. Reduce income inequality within and among countries.

-

11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

-

12. Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

-

13. Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts by regulating emissions and promoting developments in renewable energy.

-

14. Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.

-

15. Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.

-

16. Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

-

17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

As we can see, the mentioned goals cover all components of sustainable development – social, economic and environmental, and consider its institutional aspects, including systemic and structural barriers (poverty, inequality, environmental challenges, institutional structures, etc.) and their overcoming. It is noteworthy that seven goals (6, 7, 11–15) in this list are environmental (they relate to water resources, energy sources, environmental sustainability of cities and settle- ments, climate change, ecosystems of land, seas and oceans, etc.).

The comparative analysis of the content of the SDGs and the directions (targets) of environmental investment outlined above allows us to conclude that a significant part of them are not only interconnected, but also complement each other, and their joint solution can give, along with environmental, economic and social effects (Tab. 2) .

Given the noted interrelationship and complementarity of the SDGs and environmental investment goals, we can say that the latter can be considered as responsible in their essence and transformative in their functional role. We must add that environmental investment can bring high profits to economic entities, under certain market conditions, primarily through the use of advanced innovation technology in a wide range of areas focused on the industrial reproduction of raw materials and the production of high-tech products from waste resources, as well as meeting their growing need for environmental protection systems; as for society, it needs new high-tech jobs in economic sectors with low CO2 emissions, the preservation of natural capital and the improvement of ecosystems, energy independence and, ultimately, the transition to a progressive (“green”) economic model.

Table 2. Sustainable Development Goals and priority areas for environmental investment

|

Main priorities of environmental investment |

Sustainable Development Goals |

||||||||||||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

|

|

1. Improving resource efficiency (e.g. waste reduction, energy efficiency) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||||||

|

2. Replacing traditional technologies with environmentally friendly or low-carb ones in accordance with the principles of a closed cycle (VEI, waste recycling) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||||||||

|

3. Improving the state of ecosystems and environmental quality (climate adaptation, forest planting, wetlands renewal, etc.) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||

|

Source: own compilation. |

|||||||||||||||||

The conclusion about the transformative role of environmental investments can be concretized, in addition to the above, from the standpoint of the theory of endogenous economic growth and J. Schumpeter’s well-known concept, which explain in precise terms “what the economic incentives for innovation are and how this dynamics works” (Spence, 2012).

We should note that, based on the previously identified priority areas of environmental investments, they are a priori associated with “green” innovations in the form of the latest, breakthrough environmentally friendly technology (or waste-free technology), providing deep cleaning of the final product and all target components of the environment; mandatory waste recycling and the use of alternative energy sources; production of new high-tech goods as a result of industrial reproduction of raw materials. We can argue that environmental investment gives impetus to the following radical changes in the 21st century economy:

-

• economic development will not depend on the consumption of raw materials;

-

• the use of non-renewable energy sources (oil, gas, coal) will be reduced;

-

• the technogenic impact of energy on the environment will decrease;

-

• new high-tech jobs will be created in economic sectors with low CO2 emissions, etc.

Thus, the prospects for the formation and development of such technologies are limitless, which opens up wide opportunities for innovation business, and therefore for ensuring long-term sustainable growth of TFP.

Awareness of the increasing role of environmental investments in ensuring radical economic transformations in the 21st century and in promoting long-term sustainable growth of TFP is accompanied by their positive dynamics in different countries. For example, the share of such expenses in anti-crisis packages in 2020 in South Korea reached 81%, in the EU – 59%, in China – 38%, in the U.S. – 12% (Mirkin, 2020).

At the same time, we regret to state that, despite the possibility of obtaining the previously mentioned benefits from environmental investment, Russia still faces a number of factors and barriers that restrain the effects of this type of investment; the barriers include putting the environmental goals behind the economic ones for the state and business; slow introduction of high-tech “green” innovations, including circular ones, into the economy (Lipina et al., 2018) due to outdated raw materials structure and high level of corruption; inefficient balance of the tax system; lack of a clear and understandable system of state support for such investments; uncertainty of investors in the “green” (“circular”) economy, their commitment to the current concept of production; poor development of relevant competencies in the financial sector.

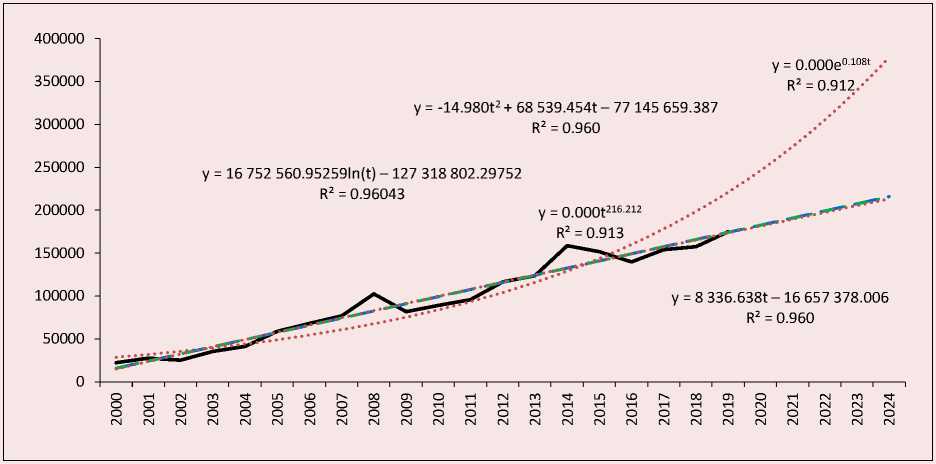

The above factors in Russia are difficult to overcome; thus, in the framework of our study we built regression models in order to forecast the volume of investments in fixed assets aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources in the Russian Federation for 2022–2024 (Fig. 3) .

The statistics of the regression models (growth curves) presented in Figure 3 are shown in Table 3 .

The analysis of the data in Table 3 allows us to conclude that the general trend in the volume of investments in fixed assets in the RF aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources in the forecast perspective can be most accurately expressed by a linear trend model with the smallest approximation error (10.39%):

Yt = 8336,63835t + 7562,04737 + e. (6)

Figure 3. The volume of investments in fixed assets in the Russian Federation aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources: Dynamics and forecasting for 2022–2024

Source: own calculation.

Table 3. Trend models (growth curves) of analysis and forecasting of the dynamics of the volume of investments in fixed assets in the Russian Federation aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources

|

Trend equation (growth curve) |

Criterion of model quality |

Forecast |

|||

|

Coefficient of determination |

Average approximation error, % |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

|

Y = 8336.63835c + 7562.04737 + g |

0.960 |

10.39 |

199304.73 |

207641.37 |

215978.01 |

|

Y = -14.97955C2 + 8651.20892C + 6408.62193 + g |

0.960 |

10.57 |

205386.43 |

214037.64 |

222688.85 |

|

Y = 25719.78432 • e °- 10756t • г |

0.912 |

16.66 |

305255.75 |

339920.03 |

378520.71 |

|

Y = 56151.83796ZnC - 23764.38378 + g |

0.8222 |

32.36 |

152299.38 |

154689.18 |

156981.41 |

|

Y = 14874.28795 • t °. 79225 • g |

0.934 |

12.50 |

178344.35 |

184460.24 |

190523.39 |

|

Source: own calculation. |

|||||

This regression model, in addition, emphasizes insufficient intensity of environmental investment, as well as the economic tools of its state support that are still poorly used in the Russian Federation.

Econometric model of the dependence of economic growth on the volume of environmental investments, taking into account their priorities

As part of an experimental testing of the proposed scientific hypothesis, an econometric model was constructed that reflects the dependence of economic growth (volume of GDP per capita in the Russian Federation) on the volume of investments in fixed assets aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources to assess the long-term and short-term response of economic growth indicators on the volume of investments, taking into account their main priorities (resource conservation and resource efficiency; improving the state of the ecosystem and improving the quality of the environment) and including lag independent variables as regressors. In accordance with the hypothesis formulated in our study, we determined the maximum values of the lag l and the degree k of the polynomial (2) describing the structure of the lag for each dynamic regression (1), while experimentally (using correlation regression analysis, testing Student hypotheses, estimates of t-statistics) we found that to estimate the regression parameters and (1) it is advisable to use 3rd-degree polynomials (7):

P j = C o + CJ + С 2р + € з / 3 ,

Yi = d0 + d 1 i + d2i2 + d3i3. (7)

Using the method of instrumental variables, in order to reduce the multicollinearity of exogenous variables, the parameters of the model (4) were evaluated for the first equation with a distributed lag of the system (1):

y1t = -25638.55 + 17.14Z 0 - 30.90Z 1 + 14.39Z 2 + et, (0.02) (0.07) (0.03)

F = 73.83, (8)

where the new instrumental values look like this (8).

Z0 = X1t + X1t-1 + X1t-2 + Xit-3 ,

Z i = X it—i + 2X lt_2 + 3Z it—3 ,

Z 2 = X it—i + 4X it—2 + 9X it—3 , (9)

Calculating the values of lag variables X 1 t –1, X 1 t –2, X 1 t –3 and variables Z 0, Z 1 and Z 2 (9) to estimate the parameters of a dynamic econometric model of the dependence of the growth rate of fixed capital investments in the Russian Federation aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources ( Y 1 t ), on the growth rate of the formation and processing of production and consumption waste ( X 1 t ), the multiple regression equation (10) was constructed:

Y1t = -25638.55 + 17.14X1t + 0.63X1t-1 +

+ 12.88X it—2 + S t . (10)

The analysis of the econometric model (10) allows us to conclude that an increase in the generation of production and consumption waste by 1 million tons in the current period in one year should be accompanied by an increase in the volume of investments in fixed assets in the Russian Federation aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources by 17.80 million rubles, in two years – by 30.68 million rubles to protect the integrity of the environment.

Since the initial data for the second equation of the model (1) have a lognormal distribution, the parameters are estimated for the logarithms of the dynamics series under consideration. The dynamic regression model of the dependence of the volume of gross domestic product per capita ( Y 2 t ) on the volume of investments in fixed assets aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources ( Y 1 t ) is as follows (11):

In^) = a + Уо1п(Уи) + У11п(Уи-1) +

+У21п(Уи—2) + - + у11п(Уи_1) + ut. (11)

Using the method of instrumental variables for the model (11), we estimate the parameters for the new variables Z 0 , Z 1 , Z 2 (12):

ln(y2t) = -9584.504 + 0.366 • Z 0 - 0.462 • Z 1 + (0,001) (0,044)

+ 0.143- Z 2 + £t , F = 201.46. (12)

(0,056)

After performing inverse transformations (5) of the model parameters (12), we obtained the second dynamic regression equation with a distributed lag (13) of the system (1):

ln(y 2t ) = -9584.504 + 0.366 • ln(y 1t ) +

+ 0.047 • ln(y 1t-1 ) + 0.014 • ln(y 1t-2 ) +

+ 0.266 • 1п(Ук _з ) + u t . (13)

The analysis of the constructed model (13) allows us to conclude that an increase in the volume of investments in fixed assets aimed at environmental protection and rational use of natural resources ( Y 1 t ) by 1% in the current period will lead to an average increase in the volume of gross domestic product per capita ( Y 2 t ) by 0.366%; by 0.413% – for the next year; 0.426% – in a year; 0.693% – in two years.

' ln(y2t) = -9584.504 + 0.366 • ln(y1t) + + 0.047 • ln(y1t-1) + 0.014 • ln(y1t-2) + + 0.266 • 1п(Ук _з ) + U t

^t = -25638.55 + 17.14 • XK +

+ 0.63^ X1t-1 + 12.88 • X1t-2 + e t . (14)

Thus, the system of dynamic regression models (14) confirms the expediency of abandoning the raw materials exporting model of growth of the Russian economy in favor of the investment model. In addition, it provides a reason to consider environmental investment as a powerful factor in ensuring sustained economic growth without harming the environment, which means the “active start” of the transformation of the Russian economy in accordance with the requirements of the global ESG agenda.

Discussion

Economic stimulation of environmental investment in Russia

Studying and generalizing the practical experience of the world’s leading countries on the use of various mechanisms and economic instruments of state policy in the field of stimulating environmental investment was the basis for the following recommendations to ensure an integrated approach to the formation of such a policy in postpandemic Russia.

-

1. Achieving a rational (marginal) value for the share of gross investment accumulation in GDP, a generalizing indicator of the stability and security of investment activity. Environmental investment, which involves replacing traditional technology with environmentally friendly or low-carbon one, improving the quality of the environment, etc., focuses on the development of knowledge-intensive and innovative and capital-intensive industries and sectors of the economy. In such circumstances, we find it appropriate to increase the share of gross investment accumulation in the GDP of the Russian Federation from the current 21.9% (2020) to at least 28–30%. Against this background, there is a need for a reliable mechanism for transforming the funds accumulated by the population into environmental investments; this can be implemented by guaranteeing full repayment of deposits in case of any defaults and accruing increased interest when they are invested in “green” securities lending to environmental investment projects.

-

2. Increasing the attractiveness of environmental investments for private capital through a policy of lowering prices for low-carbon investment projects. Such a policy means the development and

implementation of environmental standards and norms, environmental management and auditing (ISO14000, EMAS) into economic practice; the use of state guarantees for loans to clean technologies and “green” firms; rejecting the subsidies that encourage the use of hydrocarbon energy (oil, coal) and deplete natural capital, and, conversely, subsidizing clean energy and clean technology; development of a system of benchmarks to verify the “reliability” of environmental investments; creating territories (initiative of the PRC) for “testing” a system of carbon emissions trading, units of their reduction (credits or offsets, units of CO2 absorption and other carbon units). There is no doubt that such a policy requires strong political will. At the same time, it is obvious that in the end it contributes to the gradual transformation of environmental responsibility into an economic asset.

-

3. Designing a new financial and economic mechanism, the distinctive features of which are resource conservation and maximum involvement of production and consumption waste in economic turnover as adequate sources of raw materials and energy for the latest global environmental challenges. The implementation of this direction for promoting environmental investment involves:

– modernization of pricing according to the principle of social justice, which means the need to determine the full amount of production costs, including the cost of waste processing; besides, the fees for further recycling of these products (in the form of a small sum) should be paid by their consumer;

– state guarantees in the form of subsidies to reimburse part of the cost of paying interest on loans and borrowings attracted by private investors for the implementation of environmental projects;

– providing a set of benefits and preferences (for example, tax benefits and deductions, prefe-

- rential rates on loans) to economic entities that process waste using circular technology and supply secondary raw materials with improved environmental qualities, and, conversely, creating conditions under which it becomes economically unprofitable for the owner of waste to store waste (waste collection and disposal tax).

-

4. Improving environmental literacy of population and business. Urging the business and public to understand what harm to the environment and human health is caused by today’s production patterns.

Conclusion

In economics, the future is evaluated through the prism of economic development prospects, which, as we know, are specified in such a category as economic growth and are characterized by its dynamics and structure. In the current situation that has developed in Russia under the influence of an economic recession caused by the pandemic and external sanctions pressure on the national economy, the need to abandon the raw materials exporting (rental) model of economic growth in favor of an effective investment model corresponding to the requirements of the global ESG agenda, in which the environmental aspect associated with the responsible attitude of business toward nature is of fundamental importance.

Summarizing the above, we point out that our study contributes to the increment of scientific knowledge in the following:

-

1) theoretical substantiation of a scientific hypothesis that environmental investments in the conditions of planetary manifestations of environmental growth constraints should be recognized as a key factor in ensuring long-term sustainable growth of total factor productivity; the work contains original scientific judgments concerning the impact of environmental investment on the promotion of “green” innovations (environmentally

friendly technology or waste-free technology; new high-tech products obtained as a result of industrial reproduction of raw materials, etc.), capable of generating sustained economic growth in the long term;

-

2) promotion and theoretical substantiation of the scientific idea of the need to consider environmental investment as an “active start” of radical transformations of the economy in the 21st century, provided by the formation of a “green” economy; in this regard, it has been proved that it is environmental investments that are important for sustainability, but less attractive for business, that can bring profit to economic entities and satisfy their growing need for environmental protection systems; the benefits for society include creating new high-tech jobs in economic sectors with low CO2 emissions, preserving natural capital and improving the state of ecosystems, energy security and the transition to a “green” (circular) economy;

-

3) experimental testing of the hypothesis of environmental investment as a key factor in ensuring sustainable economic growth by constructing an econometric model; the model is a system of dynamic economic regressions with a distributed lag of a polynomial structure; it can be used to assess the long-term and short-term response of economic growth indicators from environmental investment;

-

4) a minimum set of necessary economic tools was proposed to be used by state policy in the field of stimulating environmental investment in modern Russia.

We note that the subject area of environmental investment is in its infancy. In this regard, it is necessary to study in more depth the nature and features of environmental investments (new investment conditions, the rate and nature of profit, payback periods, the structure of the capital market, etc.) in order to specify the mechanisms of their impact on economic growth and transformation of the economy and society.

Список литературы Environmental investment as a key factor in the formation and evolvement of an investment model for the growth of the Russian economy

- Animitsa E.G., Dvoryadkina E.E., Kvon T.M. (2020). Transformative investments – the mainstream of region development. Vestnik Belgorodskogo universiteta kooperatsii, ekonomiki i prava=Herald of the Belgorod University of Cooperation, Economics and Law, 4(83), 83–95 (in Russian).

- Banerjee A., Duflo E. (2019). Good Economics for Hard Times. New York: Public Affairs.

- Bobylev S.N. (2020). Sustainable development: a new vision for the future? Voprosy politicheskoi ekonomiki=Problems in Political Economy, 1(21), 67–83. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.375332 (in Russian).

- Bobylev S.N., Kiryushin P.A., Koshkina N.R. (2021). New priorities for the economy and “green” financing. Ekonomicheskoe vozrozhdenie Rossii=Economic Revival of Russia, 1(67), 152–166. DOI: 10.37930/1990-9780-2021-1-67-152-166 (in Russian).

- Daskovskii V.B., Kiselev V.B. (2016). Novyi podkhod k ekonomicheskomu obosnovaniyu investitsii [A New Approach to the Economic Justification of Investments]. Moscow: Kanon+; ROON Reabilitatsiya.

- Fishman L.G., Mart'yanov V.S., Davydov D.A. (2019). Rentnoe obshchestvo: v teni truda, kapitala i demokratii [Rent Society: In the Shadow of Labor, Capital and Democracy]. Moscow: Izd. dom Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki. DOI: 10.17323/978-5-7598-1913-4

- Fücks R. (2019). Zelenaya revolyutsiya: ekonomicheskii rost bez ushcherba dlya ekologii [Intelligent Growth – The Green Revolution]. Translated from German. Moscow: Al'pina nonfikshn.

- Glazyev S.Yu. (2018). Ryvok v budushchee. Rossiya v novykh tekhnologicheskom i mirokhozyaistvennom ukladakh [A Leap into the Future. Russia in New Technological and Economic Paradigms]. Moscow: Knizhnyi mir.

- Gordon R. (2016). The Rise and Fall of American Growth. New York: Princeton University Press.

- Griffiths W.E., Hill R.C., Judge G.G. (1993). Learning and Practicing Econometrics. New York: Wiley.

- Grinberg R.S. (2008). Does Russia have a future that does not depend on its commodities? Vestnik IE RAN=Bulletin of the Institute of Economics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 1, 6–21 (in Russian).

- Gubanov S.S. (2012). Derzhavnyi proryv. Neoindustrializatsiya Rossii i vertikal'naya integratsiya [Breakthrough of the Power. Neoindustrialization of Russia and Vertical Integration]. Moscow: Knizhnyi mir.

- Ivanova I.A., Busalova S.G., Gorchakova E.R. (2021). Regional investment market in the sphere of waste management: Dynamics, structure, evaluation methodology. Regionologiya=Russian Journal of Regional Studies, 29(4), 840–865. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15507/2413- 1407/117/029/202104/840-865 (in Russian).

- Jackson T. (2009). Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Earth can Publications Ltd.

- Jackson T. (2017). Prosperity without Growth? Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Routledge.

- Kormishkina L.A., Kormishkin E.D., Koroleva L.P., Koloskov D.A. (2018). Recycling in modern Russia: Need, challenges, and prospects. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 11(5), 155–170. DOI: 10.15838/esc.2018.5.59.10 (in Russian).

- Kormishkina L.A., Kormishkin E.D., Sausheva O.S., Koloskov D.A. (2021). Economic incentives for environmental investment in modern Russia. Sustainability, 13(21). DOI: 10.3390/su132111590

- Lipina S.A., Agapova E.V., Lipina A.V. (2018). Razvitie zelenoi ekonomiki v Rossii: vozmozhnosti i perspektivy [Development of the Green Economy in Russia: Opportunities and Prospects]. Moscow: LENAND.

- Matveeva L.G., Gridnev D.S. (2022). Primenenie ansamblya metodov tsirkulyarnoi ekonomiki v analize stranovykh riskov v usloviyakh neoindustrializatsii // Estestvenno-gumanitarnye issledovaniya. № 39 (1). S. 179–187. DOI: 10.24412/2309-4788-2022-1-39-179-187

- Mirkin Ya. (2020). How to resist recession: What to do? Nauchnye trudy Vol'nogo ekonomicheskogo obshchestva Rossii=Scientific Works of the Free Economic Society of Russia, 223(3), 188–196. DOI: 10.38197/2072-2060-2020-223-3-188-196 (in Russian).

- Pittel K., Amigues J-P., Kuhn T. (2010). Recycling under a material balance constraint Resource and Energy Economics, 32(3), 379–394.

- Rakov V.D. (2017). Mechanisms of support of “green” projects financing: Experience of countries. Aktual'nye problemy ekonomiki i prava=Russian Journal of Economics and Law, 11(2), 67–82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21202/1993-047X.11.2017.2.67-82 (in Russian).

- Schwab K. (2017). Chetvertaya promyshlennaya revolyutsiya [The Fourth Industrial Revolution]. Translated from English. Mosocw: Eksmo.

- Spence M. (2012). The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in Multispeed World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Spiridonova A.V. (2020). Environmental investment in the Russian Federation: A theoretical and legal approach. Vestnik YuUrGU. Seriya “Pravo”=Bulletin of the South Ural State University. Ser. Law, 20(1), 72–79. DOI: 10.14529/law200111 (In Russian).

- Sukharev O. (2019). Investment model of economic growth and structural policy. Ekonomist, 1, 23–52 (in Russian).

- Sukharev O., Voronchikhina E. (2020). Structural dynamics of the economy: Impact of investment in old and new technologies. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 13(4), 74–90. DOI: 10.15838/esc.2020.4.70.4 (in Russian).

- Yakovlev I.A., Kabir L.S., Nikulina S.I., Rakov I.D. (2017). Financing green economic growth: conceptions, problems, approaches. Finansovyi zhurnal=Financial Journal, 3, 9–20 (in Russian).