Fishing tension arcs in the Russian Arctic

Автор: Zilanov Vyacheslav K.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Social science. Political science. Economics

Статья в выпуске: 19, 2015 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The author of the article comprehensively examines the current situation, problems and possible solutions related to fishing in the Arctic. Changes in the Arctic will undoubtedly affect fisheries. In this regard, the author analyses the "hot spots" of economic activity and international relations — fishing tension arcs in the Russian Arctic, as well as the internal problems of the marine resource use.

Arctic, fisheries, the Barents Sea, the fishing tension arc, Norway, Svalbard, the United States, "ice bag", marine resources, ships

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318724

IDR: 148318724 | УДК: 639.22/639.2.052

Текст научной статьи Fishing tension arcs in the Russian Arctic

States, "ice bag", marine resources, ships

Changes in the Arctic and their impact on fishery

The Arctic, according to common views, includes the maritime areas of the Arctic Ocean, with its seas: the Greenland, Norwegian (partly), the Barents, White, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi, Beaufort and Lincoln. These marine spaces have their center in the Northern geographic pole, the southern boundary — coasts of the five Arctic states: Denmark (Greenland), Canada, Norway, Russia, the United States and form the Arctic. Addressing issues of fisheries in the seas of the Arctic Ocean, the Russian fishery in the 200--‐mile EEZ, covering the coast of five Arctic territories of the Russian Federation: Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions, Krasnoyarsk Territory, Nenets, Yamal--‐Nenets and Chukotka Autonomous Okrug (Pic.1).

Picture 1. The actual deployment of Russian fishing vessels on data for the years 2012--‐2013 (purple shading); 200--‐mile EEZs of Russia in the Arctic (blue line); Polar Russian possessions in 1926 (dashed red) and the boundary of the Arctic Circle (dashed white)

Fisheries of Kaliningrad, Leningrad and Moscow regions whose vessels are registered and are fishing in the Arctic zone of Russia are in the focus of the article. In addition, the article takes into account the results of the home fishery in the 200--‐mile zone of other Arctic states (under intergovernmental agreements) and outside — in the open waters of the Greenland, Norwegian and Barents seas where fishing is carried out in accordance with the recommendations of intergovernmental regional fishery organizations.

The Arctic waters were the arena for complex processes during the past decade. The changes occurred in the Arctic, including the Barents, Norwegian and Greenland Sea, are shown in Pic. 2.

Что меняется в Арктике, включая Баренцево, Норвежское моря ?

-

• Климат;

-

■ Введены границы 200-мильных исключительных экономических зон;

-

• Определяются пределы границ континентальных шельфов;

-

• Принимаются арктическими государствами национальные доктрины, политические цели по использованию природных ресурсов и охране окружающей среды, безопасности;

-

■ Расширяется разведка и использование углеводородного сырья на континентальном шельфе;

-

• Стремление к устойчивости в использовании морских живых ресурсов рыболовством;

-

• Увеличивается научный, экономический интерес к Арктике неарктических государств;

-

■ Набирает силу конкуренция, соперничество как среди

приарктических государств, так и между последними и другими неарктическими государствами за сырьевые ресурсы.

p icture 2. c hanges in the a rctic .

All of these processes in varying degrees affect home fisheries in the Arctic region. But, in my opinion, the greatest impact on fisheries has the climate change and the differentiation of the 200--‐mile zones (EEZ) and the continental shelf between Russia on the one hand, and neighboring states — Norway, USA, Canada and Denmark (Greenland) — on the other. Significant impact on national fishery has the competition for the use of the marine resources, as well as the race for hydrocarbon exploration and development on the Arctic shelf.

Fishing is one of those kinds of socio--‐economic activities, which have been traditionally carried out in the Arctic, mainly in the Barents Sea, the Greenland Sea, the northern part of the Norwegian Sea, and to a lesser extent in the White Sea. The southern boundary of the Arctic fisheries is the Arctic Circle. In this area, the Russian fishing fleet annually produces 1.2--‐1.3 mln tons of biological resources worth about 80--‐100 billion rubles per year. In other seas of the Russian Arctic the fishery is carried out near the coastline — local population does it in pre estuarine waters; the amount if fishing is 10--‐15 thousand tons per year; and it is used for local consumption. In 2009 the future annual amount of fishery in Russia up to the year 2020 was expected to be about 6.7 mln tons, including in the EEZ of the Russian Federation — 3.4 mln tons1.

General reserves, transboundary stocks of marine resources in the Arctic include the polar cod (Boreogadussaida (Lepechin) and capelin (Mallotusvillosus (Miiller) which have a circumpolar distribution and represent poorly isolated populations in some marine areas. The catch of capelin and polar cod is carried out only in the Barents, Greenland, and Northern Norwegian seas and in the waters of the Spitsbergen archipelago. In some years the fishery is possible in the Kara and White seas. The annual catch of these fish is defined by a condition of stocks, oceanographic conditions and the demand of the market. In some years the total catch of the arctic fish reached 2 million tons per year. Currently it does not exceed 300--‐450 thousand tons, and in some years — no more t an 150 t ousand tons 2.

Other important kinds of fish caught in the Arctic zone of Russia and in the marine areas limited by the Arctic Circle is cod, haddock, herring, blue whiting, mackerel, halibut, perch and etc. Their importance for the commercial fishery is large and their total catch is up to 3.0--‐3.5 million tons per year 3.

Today large scale fishing is only conducted in the Barents Sea, the Greenland Sea and the Norwegian Sea, where during certain periods there is produced up to 4.5--‐4.7 mln tons of fish annually, while the catch average here was 2.6 mln tons per year in the past 55 years [1]. The regular fishery in this area is carried out by Norway, Russia, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland (Denmark) and a number of EU countries. In the other seas of the Arctic fishing have been done in very limited volumes and mainly by the local coastal population for their own consumption.

After the introduction of the 200--‐mile exclusive economic zones in the Arctic Ocean and its eleven seas: the Barents, White, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi, Beaufort, Lincoln, Baffin, Greenland and Norwegian (its northern part) a huge circumpolar enclave appeared. This so--‐called “ice bag” area of 2.8 mln km2 is equal to two Barents Seas. With the melting of ice this area is becoming more available for fishing not only for the Arctic states, but for all the other states if they provide they follow the relevant provisions (for opened areas) of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea adopted in 1982.

Climate changes and possible melting of the huge ice sea area make the Arctic available for fisheries, research, exploration, extraction of hydrocarbons, expansion of shipping and other scientific and economic activity. It draws attention of non--‐Arctic states to the Arctic and causes suspicious attitudes towards the situation among the “Arctic Five”: Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Russia and the United States — members of the Arctic Council.

A number of researchers, mostly American, believe that the warming process is irreversible and by the year 2085 it will have led to the complete melting of ice not only in 200--‐mile zones of Arctic states, but also will open the central part of the Arctic Ocean, which is now a sort of “ice bag”. Another point of view is basically adhered to a number of Russian researchers, including experts of the State Scientific Center of the Russian Federation “Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute” of Roshydromet (St. Petersburg). Updated forecast makes the AARI Director I.E. Frolov and his colleagues say that instead of raising the temperature and reducing the ice cover in the Arctic until the complete disappearance of the seasonal ice in the Arctic Ocean, it is expected a lowering of the temperature and increase of iciness by the years 2030--‐2040 [2, p. 127].

As a rule, in periods of warming, the amount of most commercial species in the main areas of fisheries: Northwest Arctic, in the Barents, Norwegian and Greenland Seas. These are primarily the cod, haddock, perch, halibut, herring, blue whiting and etc. At the same time their range is expanding in the eastern and northern areas, it is especially relevant for the polar cod and capelin. Their migration to the adjacent waters of the Franz Josef Land archipelago and even to the Kara Sea should not be excluded. Arctic cod and capelin have circumpolar distribution, by the way.

Fishing in the main area, the north--‐western sector of the Arctic, is highly dependent not only on the fluctuations of the marine resources amounts, meteorological conditions, climate change, competition for resources between states, but also on the emerging legal regime here and, primarily, on the maritime delimitation between the neighboring Arctic countries.

Fishing tension arcs

In the Arctic, there are several contentious areas of interest in terms of fishing and conservation of marine resources that create tension in international relations. Every area has its own specialty and problems. The Line drawn between these areas on the map could be called the “Arctic fishing tension arc”. In the vast Arctic sea area of Russia the delimitation process has not been yet completed, especially in case of agreements with the United States on maritime delimitation in the Bering and Chukchi seas. Negotiations with Canada and Denmark regarding the limits of the continental shelf in the Arctic are ahead. Incomplete delimitation in the Arctic and its legal issues cause some tension when it comes to the economic activity, especially in areas with all year--‐round fishing and leads to the emergence of so--‐called “hot spots” in international relations and management [3, p. 33--‐34].

The Arctic zone of Russia could be divided into two main “fishing tension arcs”: the

Western arc — Norway (Svalbard area, the boundary on the shelf) and the Eastern — the United States (not ratified Agreement on the delimitation, 1990).

In addition, in the central part of the Arctic Ocean the third “fishing tension arc” appeared. It is affecting the interests of not only the five Arctic, but also other non--‐Arctic states claiming to have economic activity in the Arctic. Possible release of Arctic ice created preconditions for the emergence of unregulated fishing by vessels of non--‐Arctic states. In the area of the high seas all states, Arctic and non--‐Arctic ones, can conduct research and fish according to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982. Arctic states are actively discussing the possibility of intergovernmental agreement in order to prevent the development of the negative scenario and unregulated fishing in particular. Such an approach is in the interests of the Russian fisheries. It appears promising and timely for Russia to come up with an initiative to make a collaborative research on marine resources in the central part of the Arctic Ocean, freed from ice, by the Arctic states.

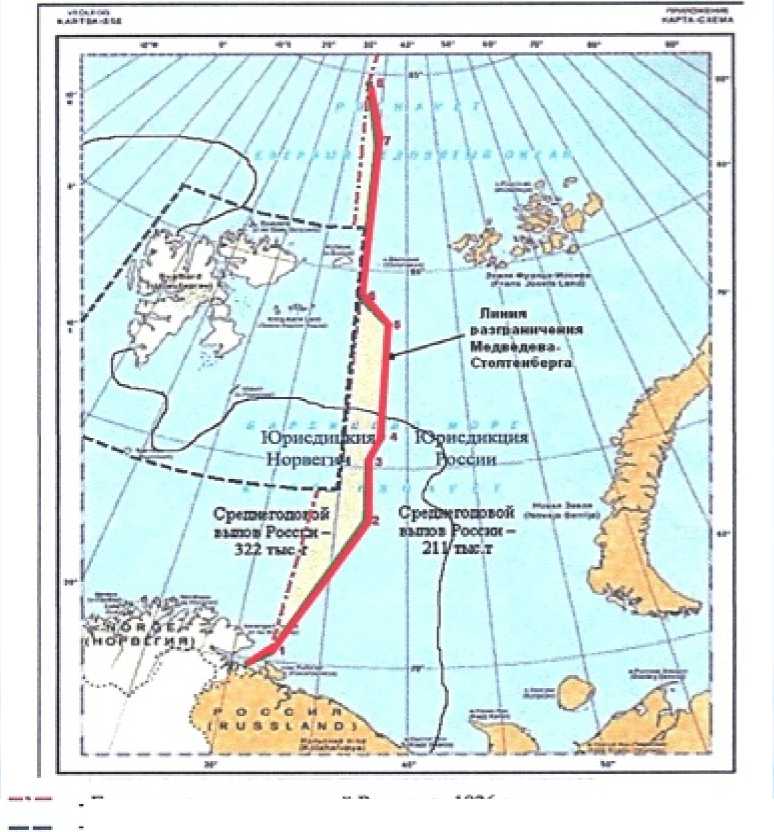

The most acute situation remains after the Agreement between Russia and Norway on Maritime Delimitation and Cooperation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean, signed on the 15th of September 2010. Some experts continue to express doubts about the validity of the decisions taken and let Norway to exercise its jurisdiction in the entire western part of the Barents Sea, which is most effective for fishing. At the same time there are problems in the fishery due to so--‐ called “protected Svalbard fishing zone”, established in 1977. It is still not recognized by Russia, believing that such a move, made by Norwegians, is contrary to the provisions of the Treaty on

Svalbard signed in 1920 [4] . For the first time in history of Russian--‐Norwegian fishing relations we can speak about the legal framework that led to the dependence of our fisheries in these areas from the Norwegian authorities. Primarily, this concerns the fishing areas in the waters close to the Svalbard archipelago.

In this regard, it remains an acute problem of ensuring the smooth operation of the Russian fishing fleet in the western part of the Barents Sea, including the area of Spitsbergen. Despite repeated

Russian proposals within the SRNK, uniform fishing rules for these areas do not exist, as well as the agreement between Russia and Norway concerning the fishing control and sanctions in case of violation of the fishing regulations and a number of other provisions. “Analysis of the court decisions in

Russia and Norway shows that the courts give different estimates for the legal status of the sea area near the Svalbard archipelago. At the same time, Norway delays the decision on distribution the Treaty on the Svalbard archipelago to the sea area” [5]. In this case, the maritime delimitation line is set far to the east from boundary of the polar lands Russia, as it was in 1926 (pic. 3).

-

- Граница полярных владений России от 1926 г.

-

- Граница района Договора о Шпицбергене 1920 г.

■■■ - Линия разграничения {граница} Баренцева моря и Северного Ледовитого океана между Россией и Норвегией от 2010 года.

—^— - Граница ледового покрова в холодные годы.

-

- Уступленный Л.Медведевым шельЛ России в пользу Норвегии площадью около 80 тыс. кв. км.

Picture 3. Maritime area delimitation between Russia and Norway in the Barents Sea.

The absence of solutions of this complex problem creates a vast field for conflicts between Russian and Norwegian fishermen regulatory bodies, strengthened by the Agreement signed in 2010. Thus, even after it, the Norwegian coast guard detained 12 fishing vessels with the flag of Russia because of different suspected acts of violating the alleged unilateral Norwegian measures regulating fisheries. A number of Russian vessels were arrested and forcibly escorted to the Norwegian ports for the proceedings in the courts of Norway. However, there are no intergovernmental agreements between Russia and Norway on such actions of the Norwegian authorities in relation to our fishing boats there. The question is: “What legal norms is Norway provided with to control and detain fishing vessels with the Russian flag in the open waters of the Svalbard archipelago. And why the competent Russian authorities do not take measures to protect the home fishing interests?”

Another, no less important from a practical point of view, question of fisheries is resulting from the provisions of the Agreement signed in 2010. It is the refusal of the Russia from the part of the continental shelf in the area east of the border of the polar lands of Russia, established in 1926 and still relevant in the present. As I have repeatedly stated in various publications, Russia refused from a part of the continental shelf in favor of the Norway. Only in this area between 74° NL and 81° NL Norway got 80 thousand km2 of continental shelf. Besides, in the long term perspective, the Russian fishery may be disposed in the eastern zone of the Barents Sea, in so--‐called “ice bag”, as the area has the increased ice cover.

Some articles, devoted to the consideration of provisions of the Agreement signed in 2010 and issues related to fishing, in my opinion, contain rather subjective data on Russian losses of the continental shelf areas [6]. Currently, in these areas and in the Barents Sea (outside the Russian 200--‐mile zone, where the shelf must be owned by Russia) we are able to observe unregulated and uncontrolled fishing of the snow crab. This marine biological kind refers to the “sedentary species”, which, in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982, is under the sovereignty of the state — owner of the continental shelf. In other words, without the consent of the State, the owner of the continental shelf, no one can fish and research “sedentary species”. In this regard, the position of some Russian authorities is unclear when they are referring to the Agreement signed in 2010 and saying that these are the “open waters outside the 200--‐mile zone of Russia”. It seems to be logical then and ask an important question: “What was delimited by Russia and Norway in the area between 74° NL and 81° NL? And what is the significance of this boundary line?” The failure to settle the problem between Russia and Norway and its different interpretations by the Foreign Ministry and the FSB creates significant “stress” in the fishing areas in the North--‐West Arctic.

Of course, the final settlement of the problems discussed above and their proper legal decision won’t remove the “arcs of tension". However, the need to protect the home fishery in the Arctic and fight for a coherent policy, management, conservation and use of marine resources, as well as for the control of fishing by neighboring Arctic states.

Internal problems of the marine resource use

At the federal level, the main priorities and goals of the state policy in the fisheries are formulated in the Food Security Doctrine of the Russian Federation, approved by presidential decree, January 30, 2010 №120; Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation until 2020 approved by the Russian President, July 27, 2001; the Concept of Fisheries Development of the Russian Federation for the period until 2020, approved by the Russian Government, September 2, 2003 № 1265--‐p; and in other fundamental documents4. The federal budget support for the Russian state program “Development of the Fisheries Industry”, approved by the Government of the Russian Federation on the 15th of April 2014, amounts to more than 83.1 billion rubles5. However, the implementation of the state program is still doubtable due to the crisis and sequestration of budget.

In 2014 the total catch of fish in Russia amounted to 4.215 mil tons, which is 81.1 thousand tons or 1.9% less than in 2013. In the Northern basin it was nearly 570 thousand tons, which is also less than in the previous year (43 thousand tons less). Catches of cod amounted to 515.7 thousand tons (slightly more than in 2013), catches of haddock — 78.5 thousand tons (a decrease of 7.3 thousand tons). Catches of capelin fell significantly — 35.8 thousand tons and 25.7 thousand tons in total6. In the Kara, Laptev, East Siberian and Chukchi Seas large scale fishing is not done due to the lack of fish stocks and the climate peculiarities — low temperatures, ice and poor phytoplankton. Fishing in rivers does not exceed 10--‐15 thousand tons and it is used mainly to supply the local community.

In connection with expanding exploration, production and development of hydrocarbon in the Barents Sea, there is a threat of pollution of the Arctic environment and the negative impact on marine resources and fisheries. Therefore it is necessary to take special measures, aimed at protecting the Arctic environment and marine resources during the exploration and development of hydrocarbons on the Arctic shelf. In some parts of the shelf with spawning fish and high concentration of juvenile fish such activities should be prohibited.

In the Arctic western zone large scale fishing, carried out by Russian vessels, is done in accordance with the regulations adopted at the national level, as well as on the basis of agreements signed together with the neighboring states — Norway, Denmark (Greenland and the Faroe Islands) and Iceland and with the special attitude to the recommendations of international organizations — the ICES and the NEAFC. Control of fisheries in the Russian exclusive economic zone and on the continental shelf of the Russian Arctic is provided by the BS FSB. If Russian vessels fish within the 200--‐mile zones of other Arctic states — Norway, Denmark (Greenland and the

Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland and Canada, they are under control of the relevant authorities of the states. BS FSB carries out specific service function without appropriate experience and training, which leads to conflicts with the fishermen and “pressure” for business. It seems appropriate to transfer these functions to the Federal Agency for fishery, as it was before.

The fundamental legal acts on fishery in Russia are: the Federal Law “On fishing and preservation of aquatic biological resources”7 and Regulations on Fishery in the Northern fishing basin 8. There are also some more adopted and developed legal documents but they require a number of amendments. Some amendments required on the status of “scientific” catches, coastal fishing, exploratory work to provide the fishing fleet with the resource base and exploration of new areas and target species. Payments for the use of marine resources in the Arctic region (such a rule is not present at any of the Arctic States) should be removed, as well as the delivery of the catch from the fishing area of Spitsbergen in the Russian ports 9. These rules lead to the annual rise in the cost of fish products delivered from a remote from the Russian territories port of Spitsbergen up to 1.5--‐2.0 billion rubles. Every ship loses more than 4--‐5 days on delivery and the time to unload as well.

There are problems related to the modernization the fishing fleet. Russian fishing is done in the Arctic zone and it is based on the established total allowable catches (TACs) for the stocks of 120 units in a 200--‐mile exclusive economic zone of Russia, including to the Arctic zone. These TACs were set by national scientific institutions, taking into account the precautionary approach and the fishery is carried out with the traditional fishing gear: trawls, longlines, partly fixed and draft nets and other fishing gear. As I have noted earlier, 98% of annual catch is trawling one. The fishing is carried out by 350 different classes of vessels. However, 60% of vessels are over the age of 16--‐20 years 10.

At the same time 78 ships in the North Basin are modernized and repaired, some of them were built and purchased abroad by Russian ship owners. All of these vessels sail under the Russian flag, and their owners are the Russian campaigns. However, when it comes to paying taxes (VAT and customs duties) they usually do not go in Russian ports, preferring to be unloaded, supplied in ports in Norway, or using transportation services directly from the sea. We are talking about the most modern and high--‐performance vehicles. However, they cannot be moored at the dock in their native town of Murmansk, because it is necessary to pay VAT and customs duties — only 23% of the total value of the vessel. Ship owners have no such means, and to take credits with the existing rates is a strait way to ruin the business. As a result, these vessels are fishing, use our quotas, carry the Russian flag, and their owners are Russian companies and citizens of the Russian Federation but the vessels are supplied and unloaded in foreign ports, mostly in Norway. In addition, the level of service for our ships in the ports of Norway exceeds the level of service at the ports of Russia. If these vessels were supplied, repaired and provided with other services, Murmansk would have 6--‐7 billion rubles annually and 1 thousand of new working places 11. So, it also has an important social component. Coming back to the home port, the fisherman would see his family more often and the public would be able to see modern fishing vessels.

The issue of 120 ships that are not using the Russian ports in the Northern Basin and the Far East is solved by the introduction of certain conditions for fishermen. There are some legal changes preparing now for the draft of the fishery law and the draft of a bill for custom amnesty for such ships that may provide them with a zero rate for custom clearance. This was announced by the Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Head of the Federal Agency for Fisheries I.V. Shestakov during his visit to Murmansk in February 2015 12.

In general, in case of modernization and purchase of new vessels, the existing fishing fleet of the Northern and Western basins is capable to provide a full catch for national quotas for marine resources in the Arctic seas. However, it is important to start an accelerated upgrade scientific research, the creation of a search fleet for fishery research and monitoring of stocks, marine resources and the environment, not only in the Arctic seas, but also in the central part of the Arctic Ocean. It is necessary to construct new research fleet adapted to Arctic ice conditions. It should be noted that a number of Arctic states, Norway in particular, has already started the construction of such a lead vessel for complex research in the Arctic, including the study of marine resources. In specialists’ opinion is much more profitable to construct modern ships than to import the fish. It is extremely necessary and beneficial for the national food security to invest in the development of Russian fishery fleet [7, p.5].

Conclusion

In conclusion, it should be noted that the changing climate in the Arctic creates the preconditions for the expansion of economic activities, especially fishing, in the 200--‐mile zones of the five Arctic states — Russia, Canada, Norway, Greenland (Denmark) and the United States, and

in the ice free area of the Arctic Ocean, situated outside these economic zones. It seems to be possible that the central areas of the Arctic Ocean will be free from ice and this might lead to migration of fish interesting for commercial fishery (Arctic cod, capelin, black halibut, cod, seals, etc.).

In order to prevent unregulated fishing in the central part of the Arctic Ocean Arctic states: Canada, Russia, Denmark, Norway and the United States should to:

-

a) establish a fund and adopt a program of scientific monitoring of the central part of the Arctic Ocean;

-

b) start to develop an intergovernmental treaty (agreement) on the management of marine resources in the central part of the Arctic Ocean and their preservation;

-

c) carry out experimental scientific fishery in the central part of the Arctic Ocean basing on scientific advice and monitoring of marine resources taking into account the environmental aspects of research, fishing and the vulnerability of the Arctic environment.

Arctic states are in need of strong diplomatic actions aimed at solving the existing problems in the areas of the “fishery tension arcs” in the Arctic and help to build trustful relationships between them.

Taking into account that a large part of Russia's 200--‐mile zone of the Arctic has recently become free from ice for a long time during the year, it is important to proceed with the construction of a special research fleet to carry out comprehensive research in these areas.

In order to improve the efficiency of the fishing fleet in the Arctic zone and to increase its contribution to food security of the country, it is necessary to remove the existing administrative barriers, including so--‐called “non--‐mooring vessels”, and to create the right conditions for efficient service for fishing vessels in Russian ports, which should be better than foreign seaports.

There is no doubt that further improvement of the legislation in the field of fisheries and its enforcement, as well as modernization of the fishery management in Russia, including the Arctic area and the Northern Basin, is needed. Successful solutions of problems in the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation and food security are largely dependent on the funding and implementation of the Russian Federation State Program “Development of the Fishery until 2020”.

Список литературы Fishing tension arcs in the Russian Arctic

- Vylegzhanin А.N. Morskie prirodnye resursy: Mezhdunarodno-‐pravovoĭ rezhim [Marine resources: international legal regime]. Moscow, SOPS Minekonomrazvitiya RF i RАN, 2001. 298p.

- Zelenina L. I., Аntipin А.L. L'dy Аrktiki: monitoring i mery adaptatsii [Arctic ice: monitoring and adaptation mmeasures]. Аrktika i Sever, 2015, no. 18, pp.122—130. Available at: http://narfu.ru/upload/iblock/828/08-‐_-‐zelenina_-‐antipin.pdf(Accessed 20 March 2015).

- Lukin Y.F. “Goryachie tochki” Rossijskoj Аrktiki [“Trouble spots” of the Russian Arctic] Аrktika i Sever, 2013, no. 11, pp. 1-‐35. Available at: http://narfu.ru/upload/iblock/b6d/01. pdf (Accessed 20 March 2015).

- Zilanov V.K. Rossiya proigryvaet Barentsevo more [Russia is losing the Barents Sea]. Materialy 4-‐j mezhdunarodnoj nauchno-‐prakticheskoj konferentsii [Proc. 4th Int. Conf.]. Murmansk: MGTU, 2012, pp. 167-‐175.

- Sennikov S.А. Pravovye aspekty osushhestvleniya rybolovstva v morskom rajone arkhipelaga Spitsbergen [Legal aspects of fishing in Spitsbergen archipelago marine area]. Rybnoe khozyajstvo, 2014, no. 4. Available at: http://tsuren.ru/wp-‐content/ uploads/ 2014/09/rh-‐4-‐2104.pdf (Accessed 21 March 2015).

- Bekyashev K.А. SBER — effektivnyj mekhanizm sotrudnichestva v Barentsevo-‐Evroark-‐ ticheskom regione [BEAC-‐ the effective mechanism of cooperation in the Barents Euro-‐ Arctic region]. Rybnoe khozyajstvo, 2013, no. 6, pp. 27-‐30.

- Ivanov А.V., Teplitskiĭ V.А. Eshhe raz o perspektivakh rossiĭskogo rybolovstva v otkrytykh raĭonakh Mirovogo okeana [One more time about the perspective of the Russian fishing in the waters of the World ocean]. Rybnoe khozyajstvo, 2014, no. 4, p. 5.