Generation y in Russia: social stratification, position in the labor market and problems of political socialization

Автор: Belyaeva Lyudmila A.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.13, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article analyzes the youth's problems affecting their life and social well-being (social stratification of society; the position and behavior of youth in the labor market; changes in the youth's value orientations and models of socio-cultural behavior). The article describes the social status of the youth population in Russia, their integration into the labor market and the emotional component of political socialization. The authors analyze the age groups assigned to generation Y in accordance with the gradation of V. Strauss and N. Hau. The young people's material standard of living, education and place of residence are the indicators that differentiate the Russian youth, creating a kind of stratification youth pyramid. Currently, the place of young people in the labor market is decreasing, while the share of the employed aged 55-72 is growing, which negatively affects the innovative development of the economy. Services have become the dominant industry for youth employment. The socialization of modern youth is contradictory, which is due to deep social differentiation, unstable position in the labor market, the impact of global information processes, the opposition of a tolerant attitude to otherness and independence and intransigence to other points of view and behaviors that differ from traditional ideas and values within the society. The political socialization of young people is characterized by a low level of interest in politics, a more critical attitude to the democratic status of the country when the respondents grow up with an increased positive emotional component in relation to the Motherland. When comparing some of the characteristics of these generations in the Russian Federation with the characteristics of the youth in European countries at different levels of development, Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain, Germany, and Sweden, their uniqueness is revealed, due to the severity of many problems of economic and democratic development in Russia. The data from Rosstat, the author's empirical research, and the European social research (ESS) were used in the study.

Social stratification of youth, labor market, political socialization, education, values

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147225478

IDR: 147225478 | УДК: 332.1 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2020.4.70.13

Текст научной статьи Generation y in Russia: social stratification, position in the labor market and problems of political socialization

At the late 20th – the early 21st century, the problems of youth and, more broadly, the problems of generations, their change, transfer of value experience, and continuity of social practices became some of the most important aspects for preserving the integrity of society as a system and the dynamism of its development. In recent years, several monographs, which address the current and new problems of young generations just entering this world and those who became quite familiar with it and begin to influence society, even if members of these groups deny it trying to stay “non-adults”1 for as long as possible, have been published [1; 2]. A range of research problems of young people is quite extensive [3–5]. For example, the Generation Research Center, established in the UK, studies generations’ living standards, opportunities that young people have for their own development, and the implementation of family and social contract between generations – support for older age groups2. Scientists in different countries unanimously recognize significant differences between young people and older age groups, find common features that are determined by the immersion of young people in virtual reality with the formation of a new system of values [6; 7].

The article focuses on several problems of young people that affect their life and social well-being. First, it is the problem of social stratification of entire society, in which generations of young people occupy their dynamically changing differentiated place, forming a hierarchical youth pyramid; second, young people’s position and behavior on the labor market due to its contradictory changes and the emergence of new forms of employment; third, the transformation of value orientations, models of socio-cultural behavior of young people, which do not apply to the entire cohort and indicate the absence of a single value system among young people and in society as a whole, which continues to differentiate according to various reasons, including age and generation characteristics.

Theoretical basis for the study of youth groups

Next, we will focus on the highlighted issues, but, first, we need to define the term “youth”. The most commonly used characteristic of youth through its social functions is presented by K. Manheim. “The problem is that, although there is always a new generation and youth age groups, however, the question of their usage depends on the nature and social structure of given society. Youth is among hidden resources that exist in every society, and its viability depends on these resources’ mobilization ... A special function of youth is that it is an enlivening intermediary, a reserve that comes to the fore when such revival becomes necessary to adapt to rapidly changing or qualitatively new circumstances” [8, p. 571–572]. The function of youth as an engine of society’s innovative development, noted by Manheim, does not contain any references of age characteristics, age boundaries, which is not important in this definition, especially since these boundaries are mobile and limited depending on historical stages lived by society.

The most common definition in Soviet, and now in modern Russian, sociology is the one from I. Kon: “Youth is a socio-demographic group distinguished on the basis of a combination of age characteristics, features of social status, and socio-psychological properties caused by both. Youth as a certain phase, or stage of a life cycle, is biologically universal, but its specific age limits, associated social status, and socio-psychological features have a socio-historical nature and depend on the social system, culture, and socialization patterns inherent in this society” [9, p.85]. According to the socio-cultural approach, young people may be considered a socio-demographic group with a common system of values, worldview, behavior standards, and subculture. However, in modern Russian conditions, we can talk about the multiplicity of its socio-cultural forms, which are formed under the influence of society and youth’s differentiation processes.

The upper age limit for young people is now 30 years. It is when most young people finally determine their professional path, end their education, and start their own families. At the same time, there are tendencies toward the expansion of this boundary, as many youth roles continue to be performed at a later age. Previously, with a shorter training period, the upper limit of young age was lower. The lower age limit is also agile and varies among different researchers in the range of 14–18 years. However, there is a research practice when young people are divided into internal age groups, for example: 14–18 years old teenagers,

18–24 years old young people, 25–29 years old “young adults”, and other gradations, including ones reaching the upper limits of 35 years.

The systematization of generations, following development of American scientists V. Strauss and N. Howe, became popular [10]. The selection of young people generations is currently associated with significant events in the world of digital technologies and development of computer networks. For young people, there are large groups, such as Millennials, or generation Y (born between the early 1980s and the late 1990s; at the beginning of 2018, they were about 18–35 years old [2]), and younger groups, such as the “digital generation” (generation Z) born after 2000. These gradations are important not only for studies on young people’s social characteristics, but these also have a commercial meaning for manufacturers of certain products, especially related to fashion and IT spheres.

However, it should be recognized that the nuances of age classification are not fundamentally important; it is more like the subject of researchers’ agreement who are focused either on different stages of young people’s life path (growing up, professional selfdetermination and beginning of work, search for their place in the socio-professional structure of society, and performance of family functions), or certain significant events in development of a particular society, and who would like to be able to compare the results of their work. The logic of differentiation of young people is present in Rosstat’s traditions: its studies currently identify age groups of 15–19, 20–24, 26–29, 30–34 years; in other gradations, the range of 30–39 years is used instead of the last group3. In other words, there are many options for young people’s age classifications, and, for the purposes of specific analysis, it is possible to abandon a standard solution for performing research tasks.

Research methods and methodology

Data of ESS (European Social Survey) is used in this article: it has been conducted in most European countries since 2002, including Russia (since 2006). In Russia, the research is carried out by CESSI (Institute for Comparative Social Research).

Information is collected during a personal interview at home with 15-year-old, or older, respondents on a random probabilistic sample. The sample size was 2.430 respondents in 2016. In the article, countries are selected for comparison of data depending on the duration of their presence on the market economy system, the development level of economies, and the stability of democracy.

Two generational gradations were used for the analysis presented below. The first is based on Rosstat-selected groups of youth in the range of 15–29 years (divided into groups of 15–19, 20–24, 25–29 years), the second-generation Y (18–34) years divided into two cohorts: 18–24 and 25–34 years.

Results and discussion

Based on two fundamental definitions – youth as an engine of society’s innovative development and youth as a carrier of social and psychological characteristics that depend on age – we will overview aforementioned current contexts related to the position of young people in Russian society.

First, we would like to note some alarming quantitative trends that characterize a changing position of young people in Russian society. In 2017, according to Rosstat, the share of young people, aged 14–30, in Russia was 29.4 million people, or 20% of the country’s population. At the same time, in just 4 years – from 2013 to 2017 – its population decreased by almost 5 million people, or 5 p. p.. Majority of young people live in towns (75.6%), 24.4% – in rural areas (2016). Russian regions significantly differ in the share of young people among population, and this situation, according to Rosstat forecasts, will remain in the near future. According to an average version of the forecast for 2025, a minimum share of youth among population will be observed in Moscow – 14.42% and St. Petersburg – 14.92%, a maximum share – in the Chechen Republic, the Republic of Dagestan, and Ingushetia – 26.72, 23.87 and 23.26%, respectively. Currently, these regions have more than 30% of young people4 among population and one of the highest rates of youth unemployment. It is obvious that, in order to prevent negative social events in these regions, it is necessary to provide more employment for young people.

Such unfavorable trends, related to a number of young people, determine a possible alarming level of demographic burden in the future. By 2035, according to Rosstat’s average forecast, there will be 834 disabled people per one thousand people of working age, including 287 children, aged under 14, and 547 people who are over working age. In the Kurgan region, a demographic load of more than one thousand disabled people per one thousand able-bodied people is predicted5. It makes us more and more apprehensive about the future; in particular, analysis of a current position of young people in Russia, trends of their socialization, involvement in the educational system, participation in social production, and the impact on the society’s value-normative system, which will increasingly be determined by the generations that currently belong to the youth cohort.

Young people in the system of social stratification

There are three major criteria that determine the position of a young person at the current stage of Russian society development: material level of life, education, and place of residence. All three criteria not just differentiate young people themselves but also project the stratification of families and regional communities, where a young person lived or lives, on them. The hereditary factor more and more influence a place in society. Relative social homogeneity during socialism was replaced by deep stratification, which definitely affected young people’s social status.

According to some researchers, in Soviet Russia, finances were not the most significant indicator of status, but now it is one of the most important indicators. A new system of social coordinates emerged, corresponding to new economic and political relations. In this regard, the system of criteria or status indicators, which determine a position of an individual or a group in the social hierarchy, became more complex [11]. Material differentiation and social status of adult population affected material and social status of young people from different income and social strata and opened up different channels of social mobility for them. The problem is aggravated by deep differences between regions [12].

How do young people assess a financial situation in their families? According to ESS, young people are more optimistic than adults in the Russian Federation. Only 7 and 10% of young people, aged 15–24 and 25–34, respectively, believe that it is very difficult to live on their family income, while 26 and 32% find it quite difficult. For adults, aged 45–59 and 60+, these estimates are more alarming (Tab. 1).

In order to more objectively assess the level of financial provision among young people in Russia, we may compare the estimates given by Russian young people and their peers from several countries of the former socialist camp (Poland, Czech Republic), Southern (Spain), Central (Germany) and Northern (Sweden) Europe. While 60% of Russian young people, aged 15–24, responded that their families can live on received income without experiencing financial difficulties, or that this income is basically enough, then, in Poland, 90% of this age group members provided this assessment of income, in the Czech Republic – 68%, in Spain – 77%, in Germany and Sweden – 91%. In the group of 25–35-year-olds among listed European countries, there were similar estimates of financial well-being, with the exception of Spain, where 10% fewer young people of this age rated their family income as sufficient or not causing any financial difficulties. In Russia, there is also 7% decrease of this age group size with such estimates of family income compared to the group of 15–24-year-olds. It should be noted that

Table 1. Which statement most accurately describes your family’s income level?, %

Russia, age (years) 15–24 25–34 35–44 45–59 60+ We live on this income without experiencing financial difficulties 8 8 6 7 5 This income is basically enough for us 52 45 45 39 35 It is quite difficult to live on such income 26 32 33 35 39 It is very difficult to live on such income 7 10 11 15 20 Hesitate to answer 7 5 5 4 1 Total 100 100 100 100 100 Source: ESS-2016 data. Available at:

insufficient income has a negative impact not just on the level and quality of life but also on prospects for obtaining a good education in the group of 15–24-year-olds, as well as on life activities of young people, aged 25–35, especially if they already have children.

According to ESS and other studies, the largest share of people without financial difficulties in Russia is entrepreneurs. It is safe to assume that this group of people has the best financial opportunities to provide children with a good quality education, abroad too. The same is relevant for the managerial and cultural elite. However, it needs to be pointed out that the group of small and mediumsized entrepreneurs, as well as a group of selfemployed people, is very narrow in Russia, and unfavorable trends of its development remain. Each year, experts note “unpredictability and aggressiveness” of government policy, “constantly tightening business rules, its constant change, and strengthening of punishing policy of all regulatory authorities”, “constant appearance of new requirements”. The “high level of bureaucracy” and “cronyism of official apparatus” also do not contribute to improving the business climate in Russia6. The government’s efforts to liberalize conditions for entrepreneurship and self-employed people are aimed at simplifying business development, but it is too early to draw any conclusions. Despite existing difficulties, many entrepreneurs are ready to transfer their business to children, if they are interested in it, and intend to prepare kids for this: in particular, by providing them with good education7.

Those who have parents with higher education are more likely to become specialists, while young people from working families usually receive secondary vocational education and take jobs on the labor market. Almost all children of managers graduate from universities [13]. There is a steady trend of transition to the middle class of young people whose parents were also “middle class”. This is how the social stratification of Russian young generations develops. The influence of family’s socioeconomic status on the choice of educational and professional strategy by a young person is very significant and primarily consists of personal support for a desire to achieve a certain status and advantages – financial and social – that the family has to implement such a choice. In this case, it is possible to note a decisive positive influence of cultural capital, accumulated by generations of parents during the Soviet period, on the formation of young people’s cultural capital. The prestige of education did not decrease a desire of families to provide children with higher education even in the post-Soviet decades of a sharp decline of specialists’ living standards and the reduction of intellectual labor market, although the quality of university education declined throughout this period, and university years were often seen as a young person’s stage of socialization, not the acquisition of in-demand profession. As the result of the educational “boom”, 24.7% of employed people had higher education in 2000, and 34.2% – in 20178. We do not take into account the quality of training and note only quantitative changes.

There is a strong correlation between living standards, a place of residence in different types of localities, and distance from capitals and large towns. As shown in the monograph

“Income Stratification Model of Russian Society: Dynamics, Factors, Cross-country comparisons”, in 2017, in Russian capitals – Moscow and St. Petersburg – high-income population groups made up 51% of population, in capitals of entities of the Russian Federation – 7%, in regional capitals – 4%, in villages and urban settlements – 2%. There are opposite proportions for the share of low-income population groups: in the capitals – 1%, in capitals of entities – 22%, in regional capitals – 35%, in villages and urban settlements – 45%. Smaller but still significant differences exist in proportions of average income and median income groups [14]. Family’s financial living standards directly affect financial and social position of young people when they live in a parents’ family, and indirectly – when a young person lives separately from a parents’ family or has own family and children. Regional differentiation of living standards currently determines the receiving of quality education and occupation of a central, or peripheral, place on the labor market by young people.

If we assess factors that affect the financial situation of young people and the distribution across social strata, then the first place should be given to the dependence on financial and social status of parents, their educational baggage, when a young person inherits certain material and social resources from them; relatively speaking, economic, social, and cultural capital. The second place, according to our estimates, is occupied by the localization of a place of residence, its proximity to development centers, where there are educational institutions that provide in-demand professions and qualifications, and high-quality jobs are offered. The third group of factors is the level of education received by a young person, quality of his/her socialization, an ability to adapt to social environment, become an innovator in his work area and a socially active person while choosing development directions. This group of factors depends on social and cultural capital of a young individual, his environment, personal socio-psychological characteristics, and internal motivation.

It is possible to talk about the multiplicity of the latter group of factors, which makes its unambiguous interpretation controversial in modern conditions. Now Russian young people have a variety of experiences, motivations for building a life path, and a whole range of opportunities to achieve personal and social goals. However, at the same time, for most young people, it is especially important to achieve a higher place in the social hierarchy and a good financial situation, which is considered an achievement of personal social success. According to the cultural-anthropological approach, it is determined by sociocultural factors, the success of an individual is understood as the implementation of a life strategy, formed in the system of certain cultural norms, ideas, and ideals. We would like to note that the concept of social success has a multi-faceted nature. Although, now, it is often reduced to getting a higher position in the social stratification, and it involves participation in competition, adverseness, overcoming, and winning [15]. Some Russian young people see their life path not in moving up the hierarchy but rather devote their energy to creativity, search for themselves in mastering new cultural practices, new localities, and a new lifestyle. However, for the majority of young people, the problem of integration into the modern labor market has been actualized in order to take a place in it that allows vertical social mobility.

Position of young people on the labor market

Employment, career development, and placement in a socially stratified society are largely determined by the position of young people on the labor market, and how this position relates to the position of adults and

Table 2. Structure of employed people by age group, %

|

Year |

Total |

including age, years |

||||||||||

|

15–19 |

20–24 |

25–29 |

Youth 15–29 |

30–39 |

40–44 |

45–49 |

50–54 |

55–59 |

60–64 |

65–72 |

||

|

2005 |

100 |

2.1 |

9.6 |

12.7 |

24.4 |

24.0 |

14.5 |

14.6 |

12.1 |

6.7 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

|

2010 |

100 |

1.0 |

9.4 |

13.6 |

24.0 |

25.3 |

11.5 |

13.7 |

13.0 |

8.3 |

3.0 |

1.2 |

|

2014 |

100 |

0.6 |

7.8 |

14.5 |

22.9 |

26.3 |

12.0 |

11.8 |

13.3 |

9.0 |

3.7 |

1.2 |

|

2015 |

100 |

0.6 |

7.0 |

14.5 |

22.1 |

26.9 |

12.2 |

11.4 |

13.0 |

9.3 |

3.9 |

1.2 |

|

2016 |

100 |

0.6 |

6.4 |

14.5 |

21.5 |

27.4 |

12.5 |

11.2 |

12.7 |

9.4 |

4.0 |

1.3 |

Source: Labor and Employment in Russia. 2018: Stat. Coll. Available at:

older age groups. The aforementioned trends of reducing number of young people will negatively affect the age structure of employed population, as the result, in 15–20 years into the future, there will be fewer opportunities for labor productivity growth. What can the labor market provide for young people now?

The state of the labor market in Russia in 2000–2015 is analyzed in a report prepared by specialists of the Higher School of Economics [16]. Using the results of this analysis as a “framework”, we will review the problems of integrating young people into the modern Russian labor market, especially since this aspect is presented only in fragments in the report. To do this, based on official statistics, we will highlight the main characteristics of the labor market in Russia that affect the position of young people on it and in the economy as a whole. At the same time, we use the age grouping, adopted in statistical collections, where the youth group includes people aged from 15 to 29.

Statistics show that the increase of a number of older workers in the economy changes the proportions among the employed. The result of it is the decrease of the share of young people in a total number of employed ( Tab. 2 ).

The share of young people in the economy decreased by almost 3% in 2005–2016. At the same time, the share of employed people aged 55–72 increased by 4.2%. The decrease of the share of young people in the economy certainly has a negative impact on innovative development, since young people tend to have better modern training and receptivity to new things, in particular to the introduction of digital technologies.

There have also been significant changes within age groups of young people over the last 10 years. In the group of 15–24-year-olds, the share of people, employed in the economy, decreased by about 5% due to the increase of the share of school and university students. At the same time, the share of employees in the senior youth group – 25–29 years – increased by 2.4%. Such structural changes indicate that there are more opportunities for young people to continue their education (at different levels) and only then start working.

In 2000–2018, while the primary (agriculture and fishing – from 13.4% to 6.9%) and secondary (industry and construction – from 30.4% to 27.9%) sectors decreased in terms of total employment, the service sector became the dominant sector in terms of workers’ number (its share increased from 56.2% to 65.3%)9. It has been the main place of work for young people in recent years: young people are actively engaged in trade, financial intermediation, real estate operations, and hotel and restaurant business.

Table 3. Structure of employees by age and occupation groups*, 2016, %

|

Total |

including age, years |

||||||

|

15–19 |

20–29 |

30–39 |

40–49 |

50–59 |

60–72 |

||

|

Employed – total |

100 |

0.6 |

20.9 |

27.4 |

23.7 |

22.1 |

5.3 |

|

Directors |

100 |

0.0 |

10.3 |

26.5 |

29.4 |

27.7 |

6.1 |

|

Specialists with the highest qualification |

100 |

0.0 |

23.0 |

30.4 |

23.5 |

18.7 |

4.4 |

|

Specialists with middle level qualification |

100 |

0.4 |

23.7 |

27.1 |

23.6 |

20.9 |

4.2 |

|

Employees engaged in the preparation and execution of documentation, accounting, and maintenance |

100 |

0.4 |

23.9 |

27.2 |

22.4 |

21.4 |

4.7 |

|

Employees of the service and trade sector, protection of citizens and property |

100 |

0.8 |

25.2 |

29.0 |

22.8 |

18.5 |

3.7 |

|

Skilled workers in agriculture, forestry, fish farming, and fishing |

100 |

4.2 |

13.6 |

16.8 |

19.2 |

25.5 |

20.7 |

|

Skilled workers in industry, construction, transport, and related occupations |

100 |

0.3 |

20.5 |

28.0 |

23.6 |

23.3 |

4.3 |

|

Production plant and machine operators, assemblers, and drivers |

100 |

0.2 |

17.5 |

26.3 |

25.6 |

26.4 |

3.9 |

|

Unqualified workers |

100 |

2.2 |

18.8 |

22.7 |

21.3 |

26.1 |

9.0 |

* In accordance with the All-Russian Classifier of Occupations (OK 010-2014).

Source: Labor and Employment in Russia. 2018: Stat. Coll. Available at:

In addition, young people are quite active in creating their own independent business. In 2016, 16.7% of self-employed workers were young people under 30. At the same time, young people with only secondary education dominate in this group. It is obvious that, for them, especially in rural areas and small towns, there are not enough jobs with good salaries, so they start working independently as builders, drivers, small traders, and producers of various services.

In accordance with industry and status changes, the qualification composition of employees in Russia has changed: the share of managers, highly- and medium-qualified specialists, and service workers has increased, but a number of qualified and especially unskilled workers and agricultural workers have decreased. As the result of these changes, it is not physical labor that has become the dominant economic activity of young people and all Russians in general. Jobs that require a lot of physical effort were mostly reserved for migrant workers.

Young people under the age of 30 are more represented in occupations that require higher or intermediate qualifications, in the service and trade sectors than among agricultural workers, skilled and unskilled workers, as well as plant and machine operators (Tab. 3).

The last four groups of employees, shown in the table, are not as popular among young people as the first four, if you do not take into account managers. Meanwhile, according to the Ministry of Economic Development, during 2018, the most limited supply of personnel with required qualifications was observed among working staff, and the ratio of CVs submitted to vacancies was the smallest. Young people prefer non-working professions. As the result, currently about one-third of all employees in the hotel business and financial sector are represented by young people under 30 years of age, 26% – in trade and consumer services.

The integration of young people into the labor market is controversial. Deindustrialization and slow modernization of the economy led to an outflow of young people from material production and employment in trade and services, including financial intermediation. Today, the service sector makes a significant contribution to Russia’s GDP and provides a wide range of offers for the population. At the same time, those sectors of the economy that formed the material base of the country’s economic development remain undeveloped, but did not turn out to be a priority for youth employment. The situation may change with the introduction of digital technologies in production.

Internet development and globalization created a new type of employment that is very attractive for young people – freelance. It is estimated that 20% of all activities in the IT sector are performed by freelancers, such as website creation, text processing, design and art, programming, outsourcing, copywriting, etc. In addition, freelancers receive orders for various types of engineering-production of drawings, diagrams, structures, and so on. Domestic and international freelance exchanges have emerged, the remote labor market has become international in nature, and it is becoming increasingly popular for young people who have training in digital and Internet technologies. It is attractive for the freedom of work selforganization, an opportunity to live anywhere in the world when performing custom-made work, but at the same time it carries the threat of insufficient social security.

In recent years, the informal sector of employment has become available to Russian youth with a low level of education, mainly in trade, construction, household and personal services. Seasonal work actively develops: it is work for a relatively long time outside of a permanent place of residence. Total employment grows due to the informal employment sector, and demand for services is being met. According to various estimates, informal employment in Russia is 20–25%. In Russian conditions, formal and informal sectors do not exist in isolation but actively interact with each other. The negative effect of participation in informal employment is the lack of social guarantees – payment of sick leave, pension formation, etc., as well as, as a rule, opportu- nities for professional development and social status. It is known that involvement in training and retraining depends on the place of work and level of education. The informal sector has become a haven primarily for young people with low educational levels, and additional training is often not necessary to work in this area.

Thus, Russian youth on the modern labor market actively occupy places in the informal sector of the economy (professionals – in the IT sector, young people with low levels of education, without professional training – in trade, construction and services). Despite the higher salary for young people, there is practically no social protection today, and in the future – at the onset of retirement age. The most far-sighted young people create a kind of “safety cushion” for such cases.

This group is small, but it is very difficult for its representatives to overcome their marginal position, as well as to find a good job or get a quality education. Among these young people, there are many rural residents, people with health problems and people with disabilities. The solution proposed by the authors of the report “Russian Labor Market: Trends, Institutions, and Structural Changes”, which cannot be disagreed with, is as follows: only encouragement of NEET youth representatives to obtain and improve their skills and retraining within the framework of active job search programs that would have a clear link with the requirements of the labor market, as well as creating jobs in rural areas, can lead to a reduction in the number of this group. However, over time, it can also be supplemented by graduates of low-quality universities. Their professional path is likely to be associated with low-prestige and low-skilled jobs [16]. Their main professional advantages are provided by going through socialization in a university with the acquisition of social and behavioral skills and competencies that become necessary in order to take a place on the labor market.

Table 4. Structure of unemployed young people by age group, %

|

Unemployed of all ages – total |

Age (years) |

||||

|

15–19 |

20–24 |

25–29 |

Total 15–29 year old young people |

||

|

2000 |

100 |

9.6 |

17.2 |

12.5 |

39.3 |

|

2010 |

100 |

5.6 |

20.8 |

15.0 |

41.7 |

|

2015 |

100 |

4.7 |

19.8 |

16.1 |

40.6 |

|

2016 |

100 |

4.2 |

19.1 |

16.5 |

39.8 |

|

2017 |

100 |

3.8 |

17.9 |

16.5 |

38.2 |

Source: Russian Statistical Yearbook 2018. Moscow: Rosstat, 2018. P. 124.

Most of current Russian youth face unemployment. Over the last 17 years, unemployment in Russia has decreased to the lowest levels, now it covers only 5.2% of working-age population, or 4.2 million people10. At the same time, the share of unemployed young people under 30 fluctuated in these years around 40%, amounting to 38.3% in 2017 ( Tab. 4 ).

Unemployment among young people is specific. From 2005 to 2018, the share of university graduates increased from 13.1% to 20.7% among total unemployed; unemployment remained at the level of 19–20% among workers and employees who received secondary vocational education11. Unemployment among people with other educational levels has been gradually decreasing in these years. It is obvious that, among the unemployed people who have not had any work before (26% of them), the majority are young people. How can we assess these trends of youth unemployment? The answer lies, perhaps, in the regional features of the structure of the labor market in Russia, its asymmetric state.

The lowest unemployment level is observed in the Central Federal District, the highest – in the North Caucasian FD. While young people, aged 20–29, usually have vocational education, a total number of unemployed was 34.5% in 2018 in Russia, and in such Russian regions like Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, where there are a large number of educational institutions, the share of unemployed young people among all unemployed is higher than in most other regions (38.2 and 44.1%, respectively), approaching the “leaders” of these indicators – the Chechen Republic (57.9%), Stavropol Krai (51.4%), Ingushetia (50.8%), Krasnodar Krai (50.4%). Oversaturation of educational institutions, the attractiveness of megalopolises for young people, and the reluctance to leave for the provinces, which lack jobs with decent salaries, create a situation where young people strive to stay in the capitals in all possible ways, and, it should be noted, these cities provide such an opportunity. After searching for a job for a certain period of time (Moscow and St. Petersburg have some of the lowest average job search terms for unemployed people (4.6 and 5.1 months, respectively)12), young professionals usually find it, but often it does not correspond to their specialty obtained in an educational institution. As the result, Moscow and St. Petersburg have the lowest percentage of unemployed youth, aged 20–29, among all Russian regions. In other regions with high unemployment, an average time to find a job may be twice as long.

Marked regional differences in the level of youth unemployment reflect several important contradictions between regional labor markets and the education system. Educational institu- tions in regions often do not meet the needs of the regional economy, the level of employment, the availability of vacancies, the scale of informal employment, and unemployment. Young people are not satisfied with the amount of wages and distance from development centers, especially large towns and capitals. In rural areas and small towns, where job places are limited, youth unemployment is more common than in medium-sized and large towns.

Thus, the Russian labor market and education system differentiate modern Russian youth, providing them with unequal opportunities of receiving quality education that meets, on the one hand, needs of young people for the quality of work, and on the other, the uneven distribution of well-paid promising jobs across regions. The planned reduction of budget places in Russian universities, mainly regional ones, will have a negative impact on the situation with young people on labor markets. As stated in the government’s report to the Federal Assembly on education policy, dated July 2019, by 2024, a number of budget places will be reduced by 17% compared to 2019, while a number of applicants will increase by 15%. It will primarily affect regional universities in regions where the regional budget deficit will not be able to support them. In such circumstances, subsidies from the federal budget are needed to increase free places in regional universities. Perhaps this will help to avoid a large outflow of young people to Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other major centers, and keep capable young people for development of peripheral and depressed regions.

Political socialization of youth: Role of the emotional component

Socialization is the process of integrating an individual into the social system, entering into the social environment through mastering its social norms, rules and values, knowledge, and skills. According to the peculiarities of their political culture, Russian youth is in an intermediate state, or, as P. Chaadaev said about the position of Russia between the West and the East, not clear state. The transition from a traditional society with declared socialist principles of collectivism and equalization in consumption to a modern market society with a high level of individualism and a focus on material well-being and self-realization fully affected the socialization of young people. Let us look at the example of political socialization of young people with an emphasis on its emotional component.

Today, political socialization in its most general form is one of the directions of socialization of young people, the process of their assimilation of political values and norms, which are not only transmitted from a family and government institutions but also taken from public environment and environment of direct personal and virtual communication. In Russia, as in other modernizing countries, vertical transmission of political knowledge, norms, and values of traditional society were replaced by horizontal communication. In it, the object of political socialization starts a mental, or real, dialogue with many carriers of norms, values, forms of political consciousness and behavior. It is not only a consumer of political values and attitudes, but it also influences the formation of these qualities in other people, including the older generation.

Modern Russian society is characterized by a state of transition, uncertainty in elaboration and development of political values and norms. It is manifested in the instability of citizens’ political self-identification, doubts about their influence on authorities’ actions – higher and local – and an ability to exercise their political rights. Young people’s attitude toward politics is of marginal importance, it is especially important that personal experiences and everyday reality of life lead to a sense of their own insignificance in the socio-political space and belief in the meaninglessness of political participation [17]. Just like for other age groups, young people are characterized by a high level of distrust in the authorities (with the exception of the President), political parties, and public organizations created with the assistance of government structures.

It is possible to distinguish two vectors of young people’s political socialization: positive and negative . The first one is based on a rational and emotional attitude to one’s country, its fate, its citizens, large-scale events, and critical situations; it can be the basis for political socialization and involvement of young people in public affairs and social movements. Today, this vector is implemented by young people in volunteering, self-organizing for the solution of environmental problems, in activities of non-profit organizations, in the organization of support funds, in social entrepreneurship, etc. It is possible to say that it is a basic political activity, in which the political function of self-organization and self-government is implemented. Sometimes citizens’ grassroots organizations can change the general direction of politics, influence the fate of individual politicians, municipal authorities, and managers.

The second vector – the negative one – includes political detachment, a sense of powerlessness, inability to change a situation in politics and the country as a whole, and unwillingness to show any public activity. This is what might be called the “apolitical nature” of the majority of young people, their self-exclusion from activity in public affairs, formally organized events, movements; it is manifested in a negative attitude to initiatives of government institutions, participation in activities of local authorities. Both vectors may exist in the consciousness and activities of one actor.

Our studies show that the emotional image of the country, which is recorded in population surveys, among young people in particular, may be an important component of political socialization of young people. It is primarily formed as a positive attitude to the homeland (but not the government): its nature and natural resources, concern for the ecological state and future of a territory of residence; respect for the country’s history, pride in historical figures’ activities; appreciation of the richness of cultural heritage, its place, and recognition in the world; a positive attitude to people’s qualities like responsiveness to other people’s misfortunes and a sense of justice. These meaningful and emotional assessments show dominant interpretations of the patriotism by modern young people [18], and it may be seen as the emotional basis of their political socialization.

The current contradictory stage of social development has an impact on political socialization of various groups of young people. If we turn to two age cohorts of youth –15– 24 and 25–34 years – you can see marked differences that occur due to not only age peculiarities (members of the first cohort are usually busy with education and training and live in parents’ households, and members of the second one started working and creating their own families) but also to the impact of general and the nearest social environment, as well as the impact of the information field.

To understand these differences, it is advisable to review some aspects of socialization of the youth of the Russian Federation in comparison with young people from other countries. To compare, the analysis includes a group of adults who have already gone through socialization (45–59 years).

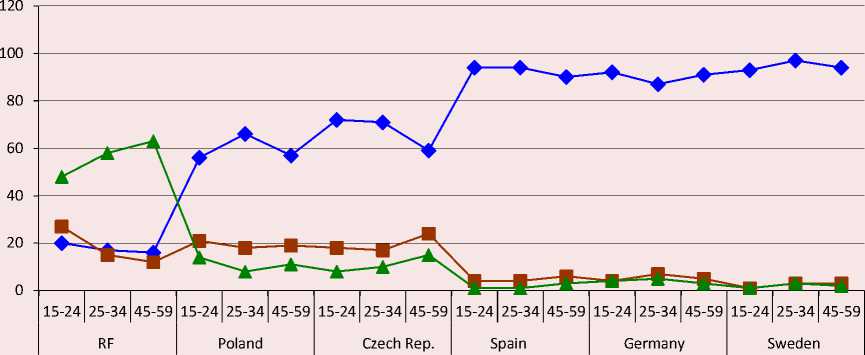

First of all, let us turn to the question of how young people in some European countries – Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain, Germany, and Sweden – relate to politics and perceive the political situation in their country in comparison with Russia. These countries were selected according to the term of their existence in the market economy system, the level of economic development, and stability of democracy. Acquired responses to the question on a degree of interest in politics (very interested, somewhat interested, little interested, not interested at all) were grouped according to positions “interested” and “not interested” (Fig. 1).

In each state, interest in politics grows with respondents’ age, but, in former socialist countries (especially the Czech Republic) and Spain, all age groups show less interest than corresponding groups of more economically developed countries – Germany and Sweden.

While assessing satisfaction with the way democracy works in their country, ratings on the contrary, decrease with increasing respondents’ age in all studied countries except Spain (Tab. 5). In Russia and the Czech Republic, the decline is maximum which shows ageing respondents’ frustration with these countries’ democratic development. We would like to note that the minimum gap in the assessments of democracy between groups of young people and adults is observed in Poland, which may indicate a greater political consolidation of age cohorts, which is absent in Russia, where the difference between various respondents, aged 45–59, 15–24, and 25–34, is very significant – more than 1 point on a 10-point scale.

In Germany and Sweden, young people’s assessment of democracy in their countries is higher than in Russia by, approximately, 1–2 points, but it decreases less rapidly with increasing age of respondents (by 0.5 and 0.6 points, respectively). Thus, assessments of

Figure 1. Interest in politics in groups including young and adult respondents, % from a number of respondents in a group

How much are you interested in politics?

■ Interested ■ Not interested

Source: ESS-2016 data. Available at:

Table 5. How satisfied are You with the way democracy works in the country? (average score on a 10-point scale)

|

Age (years) |

RF |

Poland |

Czech Republic |

Spain |

Germany |

Sweden |

|

15–24 |

5.1 |

5.0 |

5.8 |

4.2 |

6.4 |

7.1 |

|

25–34 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

5.5 |

4.2 |

6.1 |

6.4 |

|

45–59 |

4.1 |

4.7 |

4.8 |

4.5 |

5.9 |

6.5 |

Source: ESS-2016 data. Available at: countries’ democracy correlate with the level of economic development and confidence in the political institutions of society. According to numerous international studies, including ESS, the level of trust in political institutions in Germany and Sweden is among the highest in Europe, while these estimates has been low in Russia throughout the whole post-Soviet period.

The socialization of young people in Russia is influenced by ambiguous processes of the country’s political development. Until now, the conflicts that arose during the redistribution of state property have not been overcome, property and power have merged, the majority of population has been removed from the disposal of society’s resources, and there has been a deep material and social differentiation of population.

Features of political socialization of young people, their undeveloped political culture are expressed in the political passivity of young people, the lack of solidarity in the political sphere. For a significant part of Russian young people, private life, personal success, and material well-being have become more important. At the same time, young people are easily manipulated and involved in protest actions, believing that democratic procedures are only a formality in Russia.

The attitude to one’s country on an emotional level, shown by different age groups in European countries, including Russia, is indicative ( Tab. 6 ).

In all states, the emotional connection with a country increases with ageing, but, in the older youth group in Russia, it is still weaker, as well as in the adult group of 45– 59 year olds. The leader in this indicator in all age groups is Poland. Only 15% of population, aged 15–24, experience a very strong emotional connection (maximum 10 points on the scale) in Russia: 17% – 25–34 years, 27% – 45–59 years ( Tab. 7 ).

There is the above-mentioned pattern: with ageing, the emotional connection with a homeland increases, but the group of young people, in all countries, especially in Germany and Sweden, has a quite weak emotional attachment to it. These characteristics of two age groups of young people in comparison with the older part of population suggest that, along with other indicators, these are specific features of younger and older age groups. These features reflect their value orientations caused by world globalization, the spread of the Internet, mobile network connections, and relationships which more often replace real personal communication, including closest environment, and identification with a country.

Table 7. I feel a very strong emotional attachment to my country (10 points on a 10-point scale), %

Age (years) RF Poland Czech Republic Spain Germany Sweden 15–24 15 17 15 14 6 6 25–34 17 30 21 22 11 19 45–59 27 48 25 32 19 28 Source: ESS-2016 data. Available at:

Table 6. How much are you emotionally attached to your country? (average score on a 10-point scale)

Age (years) RF Poland Czech Republic Spain Germany Sweden 15–24 6.6 7.4 7.2 6.7 6.3 6.2 25–34 6.8 7.9 7.6 7.3 6.9 7.5 45–59 7.4 8.7 7.8 7.8 7.6 8.2 Source: ESS-2016 data. Available at:

Socialization of young people in modern environment in Russia is dramatic and controversial. Surveys show that entire society, including young people, is being tested for tolerance toward members of other ethnic groups and religions, labor migrants, people with physical disabilities, children with disabilities, people with non-traditional sexual orientation, etc. Young people are particularly aware of the problems of relations between people who differ in appearance, language, convictions, customs and beliefs. The socialization of young people takes place in an environment which is similar to a struggle within the whole society between fostering a tolerant attitude to otherness and intransigence to other points of view and behaviors that differ from traditional ideas and values. One of the clear examples of differences between Russian youth and young people in other European countries is the attitude toward people with non-traditional sexual orientation. Figure 2 presents data from combined responses: “completely agree” and “agree”, as well as “disagree” and “completely disagree”; in addition, the group that occupies an intermediate position between these two extreme opinions is highlighted.

In Russia, a tolerant attitude toward people of non-traditional sexual orientation (agreement with the right for their lifestyle or neutral position) among the youngest youth cohort is 47%, in the group of 25–34 years – 32%, among adult Russians 45–59 years –28%. As far as we see in other studies (Levada Center, Public Opinion Foundation), the level of tolerance toward people of non-traditional orientation in Russian society gradually increases and, at the same time, it strongly depends on the information impact13. If we compare data for Russia and other countries,

Figure 2. Attitude to persons of non-traditional sexual orientation, % from a number of respondents in the group

Should people of non-traditional sexual orientation have the right to lead a lifestyle that corresponds to their views?

—«— Agree — ■ —Somewhere in between — ▲ — Disagree

Source: ESS-2016 data. Available at: the difference will be very significant. Tolerant attitude of respondents from all countries ranges from 76 (Poland, 45–59-year-olds) to 97% (Sweden, 15–24-year-olds). Growing tolerance of young people to “others” in the Russian Federation shows that there is a growing respect for the diversity of behavioral practices. It is a demonstration of a different perception of the world by young people in comparison with adult population of the country.

Conclusions

The study allows drawing three short, but important, conclusions. In Russia, there is a social stratification of Russian young people, some kind of a youth social pyramid. Young people took their own place on the labor market, which is different from adult generations. Young people, aged 15–34, show a more critical attitude toward the country’s political system, a more tolerant perception of other opinions and lifestyles, which is different from traditional ideas and value orientations of older age cohorts.

Many researchers note that the algorithm for the change of generations’ values is common for different countries, and it is determined by key events in the world (today, it is the emergence of the Internet, the spread of mobile communications, and IT). Generational change in countries with similar levels of development takes place in almost the same mode. However, generations of young people in various countries are different depending on the stage of society development, which is well demonstrated by

ESS data, discussed above. In this regard, the theory of generations by William Strauss and Neil Howe, which received a wide response in the scientific community, requires modification for Russian conditions taking into account significant events in the country’s recent history, the level of the economy, previous features of development, and processes of intergenerational changes. Special attention should be paid to the characteristics and value orientations of modern youth (Y an Z generations), for which it is necessary to use relevant empirical material obtained in representative studies. Unfortunately, nowadays, such works are rarely carried out. Russian sociologists limit themselves by presenting the theory of V. Strauss and N. Howe and constructing their theoretical structures regarding generations in Russia. More attention is paid to the generation of 35–56-year-olds, or generation X [7, 19–21]. However, it is possible to say that generation Y, those who began an active phase of life (18–35 years), and the generation Z, those who come into adulthood (up to 18 years), even now having different socialization experiences, which will remain in the future, will form ideas about wellbeing, happiness, and their place in society. We may expect that they will claim to change the current situation in the economy, social sphere, and politics, because they will be main carriers of intangible capital in the near future [22]. This is why scientists and society should know more about these generations.

Список литературы Generation y in Russia: social stratification, position in the labor market and problems of political socialization

- Tvenge J.M. Pokolenie I. Pochemu pokolenie Interneta utratilo buntarskii dukh, stalo bolee tolerantnym, menee schastlivym i absolyutno negotovym ko vzrosloi zhizni [iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy--and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood and What That Means for the Rest of Us]. Translated by A. Tolmachev. Moscow: Gruppa kompanii «RIPOL klassik», 2019. 490 p.

- Radaev V.V. Millenialy: kak menyaetsya rossiiskoe obshchestvo [Millennials: How the Russian Society Changes]. 2nd edition. Moscow: NIU VShE, 2019. 224 p.

- Zopiatis A., Krambia Kapardis M., Varnavas A. Y-ers, X-ers and Boomers: Investigating the multigenerational (mis) perceptions in the hospitality workplace. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2012, vol. 12, no. 2, рр. 101–121.

- Raymer M., Reed M., Spiegel M., Purvanova R. An examination of generational stereotypes as a path towards reverse ageism. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 2017, vol. 20, рр. 148–175.

- Seemiller C., Grace M. Generation Z Goes to College. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2015.

- Inglehart R. Kul’turnaya evolyutsiya: kak izmenyayutsya chelovecheskie motivatsii i kak eto menyaet mir [Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World]. Moscow: Mysl’, 2018. 347 p.

- Shamis E., Nikonov E. Teoriya pokolenii. Neobyknovennyi Iks [The Theory of Generations. Extraordinary X]. Moscow: Sinergiya, 2016. 398 p.

- Mannheim K. Izbrannoe: Diagnoz nashego vremeni [Selected Works: Diagnosis of our Time]. Translated from German and English. Moscow: Izd-vo «RAO Govoryashchaya kniga». 2010. 744 p. (in Russian).

- Kon I.S. V poiskakh sebya: Lichnost’ i ee samosoznanie [Finding Yourself: Personality and Self-Consciousness]. Moscow: Politizdat, 1984. 195 p.

- Howe N., Strauss W. Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow. 1991. 544 p.

- Shkaratan O.I., Yastrebov G.A. A comparative analysis of the processes of social mobility in the USSR and modern Russia. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost’=Social Sciences and Contemporary World, 2011, no. 2, pp. 5–28 (in Russian).

- Belyaeva L.A. Regional differentiation of living standards. Mir Rossii. Sotsiologiya. Etnologiya=Universe of Russia. Sociology. Ethnology, 2006, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 42–61 (in Russian).

- Konstantinovskii D.L. Measuring inequality in education. In: Rossiya reformiruyushchayasya: ezhegodnik [Russia in reform: Yearbook]. Issue 16. Edit. by M.K. Gorshkov. Moscow: Novyi Khronograf, 2018 (in Russian).

- Modeli dokhodnoi stratifikatsii rossiiskogo obshchestva: dinamika, faktory, mezhstranovye sravneniya [Models of income stratification of Russian society: dynamics, factors, cross-country comparisons]. Edit. By N.E. Tikhonova. Moscow; St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya. 2018. 368 p.

- Jakutina O.I. The contradictive nature of social practices of success in modern Russian society. Nauchnaya mysl’ Kavkaza=Scientific Thought of Caucasus, 2010, no. 1, pp. 47–52 (in Russian).

- Rossiiskii rynok truda: tendentsii, instituty, strukturnye izmeneniya [Russian Labor Market: Trends, Institutions, Structural Changes]. Edit. by V. Gimpel’son, R. Kapelyushnikov and S. Roshchin. Moscow, 2017. 148 p.

- Shcheglov I.A. Political socialization in Russia as a problem of theory and practice. Teoriya i praktika obshchestvennogo razvitiya=Theory and Practice of Social Development, 2015, no. 2, pp. 47–50 (in Russian).

- Narbut N.P., Trotsuk I.V. Worldview of Russian youth: Patriotic and geopolitical components. Sotsiologicheskaya nauka i sotsial’naya praktika=Sociological Science and Social Practice, 2014, no. 4 (8), pp. 105–123 (in Russian).

- Semenova V.V. Sotsial’naya dinamika pokolenii: problema i real’nost’ [Social Dynamics of Generations: Problem and Reality]. Moscow: Rossiiskaya politicheskaya entsiklopediya (ROSSPEN), 2009. 271 p.

- Gel’man V., Travin D. The “squiggles” of Russian modernization: generational change and the trajectory of reforms. Neprikosnovennyi zapas=Neprikosnovennyi zapas, 2013, no. 4. Available at: https://magazines.gorky. media/nz/2013/4/zagoguliny-rossijskoj-modernizaczii-smena-pokolenij-i-traektorii-reform.html (accessed: 29.07. 2019) (in Russian).

- Matveichuk W., Voronov V.V., Samul J. Determinants of job satisfaction of workers from Generations X and Y: Regional research. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2019, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 225–237 (in Russian).

- Beliaeva L.A. Non-material capital: On the research methodology. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 2014, no. 10 (366), pp. 36–44 (in Russian).