Health-saving attitudes as a factor promoting self-preservation behavior: approaches to the study and experience in typology

Автор: Korolenko Aleksandra V.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Theoretical and methodological issues

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.14, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Under the conditions of conceptual transition of public health policy from considering citizens as passive consumers of medical services to their awareness of their own active position in health preservation, it becomes fundamentally important to understand the types of health care attitudes of the population. The aim of the study was to make a typology of the population according to the nature of health-saving attitudes and to study its influence on the dissemination of healthy lifestyle practices. We have analyzed and summarized approaches to the interpretation of health-saving motivation and classification of health care motives. We reviewed the experience of applying cluster analysis in studies of health behavior. We found that most of them use self-preservation practices as indicators for typology, while the equally important value-motivational component is most often left out of sight. Our study is designed to fill this gap. The results of the sociological monitoring of the physical health of the Vologda Oblast population in 2020 served as the information base. The motives of health care were considered in inseparable interrelation with the degree of health care and responsibility for it. We used the cluster analysis method (hierarchical and k-means method) to make a typology of the population. In the course of clustering we identified three groups of population according to the nature of health saving attitudes: 1) responsible, but unmotivated, caring little or no concern for health, 2) sharing responsibility, motivated and caring for health, 3) responsible, motivated and caring for health. We defined a socio-demographic portrait of representatives of each cluster. Representatives of the third cluster lead the healthiest way of life, while more than half of the respondents of the first cluster do not take any measures in relation to health. The results of the study have an explicit practical value in terms of managing self-preservation behavior.

Health-saving attitudes, health care, motivation, responsibility for health, healthy lifestyle practices, typology, sociological survey, cluster analysis

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147235431

IDR: 147235431 | УДК: 316.628 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2021.4.76.4

Текст научной статьи Health-saving attitudes as a factor promoting self-preservation behavior: approaches to the study and experience in typology

In recent decades, Russia has seen a conceptual transition of health policy from considering citizens as passive consumers of medical services to realizing their own active position in maintaining health [1]. In Western countries, this transition occurred much earlier – back in the 70s of the 20th century within the framework of the health promotion policy [2, p. 168]. This fact actualizes a more detailed study of the population’s attitude to their own health including individual health-saving attitudes. As noted by Doctor of Sciences (Sociology) I.V. Zhuravleva, the attitude to health is one of the central concepts of health sociology, the subjective side of which is characterized by the motives of activity in the field of health [3, p. 37, 40]. Most often, they mean a set of external and internal stimuli that encourage an individual to work to preserve health and implement health-saving behavior [4, p. 23]. The motives of health care are associated with the awareness of the importance of meeting the need for self-preservation, due to the level of development of self-preservation norms, culture, health sector, and public consciousness. They initiate an individual’s behavior to meet the need to preserve health, contribute to the choice of a strategy for self-preserving behavior, and regulate behavior based on a built-up motivational model [5, p. 17]. Motivation in the field of health largely determines the formation of appropriate attitudes toward health, interest in it, as well as the choice of forms and tools for maintaining a healthy (or unhealthy) lifestyle [6, p. 20].

In addition to motivation, an individual’s concern for his or her health is largely determined by the responsibility degree for the condition which is formed under the influence of the established social norm [3, p. 72]. That is why in a number of foreign and domestic studies, when studying attitudes toward health, personal responsibility for health is considered inseparably with motivation. The works of V. Cocker and T. Abel [7], Y. Ivanevich and M. Matteson [8], I.V. Zhuravleva, L.S. Shilova [3; 9], N.L. Rusinova and J.V. Brown [10], etc. raise the problem of individual responsibility for health as an integral element of the attitude to health.

A number of domestic studies have proved the predominance of the instrumental nature of the health value among Russians [3; 11–13]; it means that health for population is most often not an end in itself (a fundamental value), but only a tool for achieving significant goals in life. The structure of motivation in the field of health develops during a person’s life and reflects the socialization peculiarities. For example, if health is seen mainly as an instrumental value for young people, then, on the contrary, its fundamental importance increases as the body grows older and worsens [3, p. 59]. Most often, health becomes the main priority of life in old age, when a person already has chronic diseases and ailments. This fact actualizes the need to increase the fundamental value of health, stimulate motivation to take care of it from an early age. Motivation for healthy behavior should become a stable process – one of the lines of human development throughout life, and not a state in a specific period of time [14, p.116].

In addition, the gap, revealed in Russian studies between the high value of health, claimed by people and its low practical implementation [15, p. 223], determines the relevance of studying the individual characteristics of health-saving attitudes, in particular their various types among population.

Health-saving attitudes, including motivation to take care of health act as a “trigger” mechanism of self-preserving behavior, are the most “flexible” element of it, and are more subject to regulation and correction, therefore, their study can serve as a basis for the development of management tools in the direction of forming the desired behaviors in the field of health promotion.

The purpose of our work is to typify the population by the nature of health-saving attitudes and to study its impact on the spread of healthy lifestyle practices. To achieve the goal, we have implemented the following tasks: have generalized theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of attitudes to health care, in particular, health-saving motivation; have carried out the typology of the population by the nature of healthsaving attitudes on the data of a sociological survey of the Vologda Oblast population; and have studied the socio-demographic parameters of the identified types, as well as the prevalence of healthy lifestyle practices among them.

Theoretical aspects of the research

As the motivation for health care is a fundamental component of health care and acts as an internal subjective mechanism for regulating selfpreserving behavior, the review of scientific approaches to the study of health-saving attitudes will focus on it.

Motivation to take care of health for the first time appeared as a research object in the framework of social psychology . One of the most common concepts abroad has become the concept of persuasion in health benefits ( I. Rosenstock, M. Becker ) [16] according to which motives (or so-called incentives) are the driving force of health actions (Tab. 1) . It is the motives that determine the change in an individual’s behavior in relation to his or her own health, based on whether it will bring a person a “benefit” or not.

In accordance with the theory of justified actions of I. Ajsen and M. Fishbein, behavior in relation to health is primarily determined by the attitude and subjective norm [17]. If the attitude is an individual’s opinion about the possible consequences of his or her behavior and the results, then the subjective norm is nothing more than an assessment of possible reaction of other people to such behavior, expressed, among other things, in the personal motivation of compliance with social expectations. Thus, health-saving motivation in this case is an important regulator of social norms of behavior in relation to health.

Motivation to take care of health in the framework of social psychology is considered in close relationship with the category “need for health” . According to A. Maslow’s dynamic concept of needs, motives are determined by needs that have several levels: the first and lowest level is physiological (the need for food, water, homeostasis); the second is the need for freedom, security; the third is the need for love and belonging; the fourth is the need for respect; the fifth and the highest level is the need for self-realization [18]. Each new need arises only when the underlying one is satisfied. Based on this hierarchy, the need for health is a component of the highest level. The need for health is realized in health care activities, the choice of which a person makes under the influence of formed motives. Needs and motives influence each other. However, if the needs can be reflected

Table 1. Research approaches to interpretation of health-saving motivation

Based on the provisions of the concept of “psychology of relationships” (V.N. Myasishchev, R.A. Berezovskaya), health-saving motivation is an integral part of the attitude to health [15; 19]. At the same time, the value-motivational component, in which it is included, plays the role of a link between the cognitive and behavioral components of the attitude to health. The motivation of health saving is associated with the internal acceptance of the health value and the determination of the activity degree in its preservation and development [15, p. 223].

In Russian social psychology, an activity-based approach is also common in the study of selfpreserving behavior. For example, the works of N.V. Yakovleva and her co-authors consider motivation to take care of health as one of the components of health-saving behavior along with health self-assessment, health-saving attitudes, and a system of health-saving actions [20–22].

Within the framework of health sociology, there has been developed the concept of self-preservation behavior (A.I. Antonov, M.S. Bednyi, V.S. Zotin, B.M. Medkov, I.V. Zhuravleva, L.S. Shilova, L.Yu. Ivanova, G.A. Ivakhnenko, etc.). According to its provisions, the motives of health-saving are a component of self-preserving behavior and are considered in an inseparable relationship with the needs for preserving and strengthening health at all stages of human life cycle. Thus, healthsaving motives, first of all, are the motives of life expectancy. The value-motivational approach laid down in the basis of this concept is largely based on the categories of the theory of social psychology needs, but at the same time, considers health-saving activity as a kind of directly demographic behavior, and therefore recognizes its contribution to the determination of key demographic parameters: mortality, life expectancy and fertility of population [23, p. 253].

The study of the motivation of self-preserving behavior is also developing in the works of sociodemographic orientation (I.B. Nazarova [24], A.A. Shabunova, V.R. Shukhatovich [25; 26], O.N. Kalachikova, P.S. Korchagina [27], A.V. Korolenko [23], etc.). Within their framework, healthsavings motives are interpreted more broadly, reflecting not only the survival motives, but also a wide range of reasons for choosing measures taken in relation to one’s own health.

In the scientific literature, there are different approaches to the classification of health-saving motives (Tab. 2) . For example, Doctor of Sciences (Philology) A.I. Antonov divides them into econo-

Table 2. Approaches to the classification of health-saving motives

|

Authors |

Types of motives |

|

А.I. Antonov, Т.N. Shushunova, Е.S. Revyakin |

|

|

Т.V. Karaseva, Е.V. Ruzhenskaya |

|

|

I.V. Zhuravleva, N.V. Lakomova |

|

|

N.S. Grigor’eva, Т.V. Chubarova |

motif disability (can be an obstacle for studies or career development),

|

|

Source: own compilations. |

|

1 Antonov А.I. Microsociology of the family: Study Aid. Moscow: INFRA-M, 2005, p. 330.

mic, social and psychological1. At the same time, as already noted earlier, self-preservation motives are identified with the need for certain periods of life (the need for longevity). Economic motives are associated with the achievement of certain economic goals, namely, with the increase or preservation of an individual’s economic position obtaining material benefits. In this case, health is considered by an individual as an economic category that requires significant investments, and is associated with a set of opportunities related to work and income generation [5, p. 18]. Social motives are associated with the achievement of goals that consist in increasing or maintaining a certain social status by a person. They are largely determined by the sociocultural norms which have developed in society. Psychological motives determine the achievement of purely personal, internal goals of the individual (personal interest to live up to a certain age) [28]. The same classification is followed by T.N. Shushunova [5], E.S. Revyakin [28], etc.

The researchers T.V. Karaseva and E.V. Ruzhen-skaya identify the following types of health care motives: lifestyle motives (humanistic, rehabilitation and recreation, personal prestige and achievement), personal and professional development (cognitive, self-development, professional self-improvement), social environment (identification, socialization, self-affirmation associated with a sense of duty), pragmatic (competitiveness, compliance with professionally significant qualities, educational, and negative motivation) and hedonic (emotional, psychophysiological, and reflexive-volitional) [4].

The works of Doctor of Sciences (Sociology) I.V. Zhuravleva and her co-authors present another classification in which health-saving motives are considered as factors-stimuli of self-preserving behavior and are divided into such types as health deterioration, fear of possible illness, the desire to be stronger and healthier, the influence of information from medical professionals, the impact of information from the media, behavior and example of others, school education, family traditions (upbringing) [3; 29].

In this work, we have selected the following indicators for population typologization by the nature of health-saving attitudes: the range of motives that encourage taking care of health, the degree of health care severity (motivation degree), and recognition of responsibility for their own health (the level of an individual’s self-determination).

Methodological aspects of the research

A lot of works have already carried out the typology of population according to certain parameters of health-saving behavior by means of statistical methods, in particular cluster analysis. For example, based on the case study of the wave of the Dutch cohort study SMILE, there are identified three population groups by cluster analysis on five aspects of lifestyle (smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, fruit consumption, vegetable consumption and exercise): unhealthy (low probability of physical activity, consumption of vegetables and fruits, moderate probability of compliance with the norm of alcohol consumption and smoking), healthy (high probability of compliance with the norm of physical activity and alcohol consumption, moderate probability of compliance with the norm of smoking, C. Chan and S. Leung, using a cluster analysis of survey data from Hong Kong residents, identified two population models in relation to physical education and proper nutrition – “healthy” and “less healthy” [32].

In a Russian study, A.V. Zelionko and his co-authors have identified three risk groups of population by the level of medical awareness and motivation for health-saving behavior (well-being, relative and absolute risk) through cluster analysis [33]. In the work of E.P. Ammosova and her co-authors, the cluster analysis by the k-means method allows dividing the set of respondents into two groups depending on their attitudes toward their own health (passive position, active position) [34]. The study of N.M. Vasilyeva and M.D. Petrash, using clustering, carries out a typology of medical personnel depending on specific selfpreservation practices and self-assessments of health (non-smokers and non-athletes with high and average self-assessments of health; smokers, but engaged in sports and evaluating health as average; non-smokers, engaged in sports and evaluating health as good) [35]. Based on the data of a sociological survey of enterprises’ employees using cluster analysis, E.A. Riazanova has identified three types of risk-taking behavior: “low level of risk-taking, passive”, “medium level of risktaking, active” and “high level of risk-taking” [36]. Ya.M. Roshchina, based on the data of the Higher School of Economics, reflecting the practices of lifestyle in relation to health, using the k-means cluster analysis, has identified eight types of lifestyle that differ in the degree of negative effects on health, as well as the severity of its various factors [37].

Despite a large number of studies in the direction of the population typology by the nature of health-saving behavior, most of them use selfpreservation practices directly as indicators for its implementation, while an equally important value-motivational component on which the decision on the implementation of certain actions in relation to health directly depends, most often remains out of sight. Our study is designed to fill this gap and expands the understanding of the types of health-saving attitudes that have developed in the population. Taking into account such aspects as the nature of motivation to take care of health, the degree of its severity and responsibility for health in the implementation of the population typology is a pronounced scientific novelty.

The information base of the study is the results of the next stage of the sociological monitoring of the physical health of the Vologda Oblast population, conducted by the Vologda Research Center of RAS in 2020 in the form of a handout questionnaire. The survey covered the population aged 18 years and older living in the territory of two major cities – Vologda and Cherepovets, as well as 8 municipal districts of the region. The sample size is 1500 people. The sampling error does not exceed 5% (the sample is quota-based by gender and age).

In order to typologize population by the nature of health-saving attitudes, we have used cluster analysis method which allows identifying the most similar objects in the data array and combine them into groups. In our study, the motives of health care are considered in an inextricable relationship with health care degree and responsibility for it and are evaluated using the appropriate questionnaire questions and encoded variables (Tab. 3) . At the first stage, the article selects variables for clustering, they are brought to a single form (standardization). At the second step, there is performed a hierarchical cluster analysis on a random sample (30 observations) (to determine the number of clusters), followed by an iterative cluster analysis using the k-means method (for the typology of the entire population of respondents) at the third stage. The measure of similarity of objects based on the selected features is calculated using the Ward method. The square of the Euclidean distance is used as a distance measure. The work carries out statistical data processing using the IBM SPSS STATISTICS 22 application software package.

Table 3. Indicators reflecting the respondents’ health-saving attitudes

|

Questionnaire element |

Health care degree |

Motivation nature |

Responsibility for health |

|

Questionnaire question |

To what extent do you take care of your health? |

If you care about your health, what are your motivates? |

Who do you consider responsible for your health? |

|

Characteristics (answer options) |

|

|

|

|

* Those choosing this option did not answer the question about the motives of health care. Source: Authors calculations according to the questionnaire for monitoring the physical health of the Vologda Oblast population in 2020. |

|||

Main results

The typology of population by the nature of health-saving attitudes. According to the results of the cluster analysis, the respondents are divided into three groups (Tab. 4). The first group include respondents who are not motivated to take care of health, as a result, they care little or not at all for it, but, nevertheless, they recognize personal responsibility for their own health (responsible, but unmotivated, caring little or not caring for health – 41%). This type of population seems to be the most vulnerable in terms of maintaining health, as weak health-saving motivation or its complete absence, even with the awareness of personal responsibility for health, cannot ensure the effective implementation of healthy lifestyle practices.

The second group is those who mainly take care of their health, guide mainly by the need for good health, and place responsibility for its condition not only on themselves, but also on medical workers ( 45% who share responsibility, are motivated and care for health ). Apparently, for this category of population, health is an instrumental value, a means to achieve goals, as evidenced by the reliance on the need for good health when taking care of health.

Table 4. Characteristics and content of population clusters depending on health-saving attitudes

|

Cluster no . |

Characteristics of health-saving attitudes |

Cluster content |

|||

|

Health care degree |

Motivation nature |

Responsibility for health |

Abs. |

% |

|

|

1 |

They care little about their health or do not care at all |

- |

Recognize personal responsibility for health |

610 |

40.7 |

|

2 |

Mostly or very healthconscious |

Need for good health |

Responsibility for health is imposed both on themselves and on medical workers |

667 |

44.5 |

|

3 |

Mostly or very healthconscious |

The desire to increase (maintain) working capacity; unwillingness to cause trouble, to be a burden to loved ones; need for good health; unwillingness to face medicine; fear of getting sick |

Recognize personal responsibility for health |

223 |

14.8 |

|

Source: own compilation. |

|||||

The third group consists of those who consider only themselves responsible for their own health, take full care of their health, focusing on a wide range of motives: the desire to increase (maintain) working capacity, the need for good health, unwillingness to cause trouble to loved ones, face medicine, fear of illness ( responsible, motivated and caring for health –15% ). This type of population seems to be the most prosperous in terms of maintaining their own health, as it has all the necessary health-saving settings: personal responsibility for health state, expressed motivation based on a complex of economic, social, and psychological motives.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the selected types . When studying the identified types of population by the nature of health-saving attitudes, it is important to consider their socio-demographic profile in the context of gender and age characteristics, educational and family status, income level, and territory of residence.

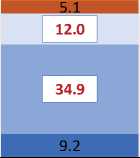

Let us analyze the gender and age characteristics of the identified types of respondents. For instance, among the representatives of the first cluster there are significantly more men (56% vs. 37 in the second cluster and 36 in the third), while in the second and third clusters, on the contrary, there are women (63 and 64%, respectively; Fig. 1 ). At the same time, men of the age group 30–60 years are more common in the first cluster (35% vs. 21 in the second cluster and 22 in the third), as well as 60 years and older (12% vs. 9 in the second cluster and 8 in the third). In turn, among the representatives of the second cluster, there are more women aged 55 years and older (29% against 20 in the first cluster and 25 in the third). The third cluster more often included middle-aged women – 30–55 years (31% vs. 19 in the first cluster and 25 in the second).

As for the differences in educational status, people with incomplete secondary and secondary education are more common in the first cluster (13% vs. 6 in the second and third clusters), as

-

Figure 1. Population clusters by the nature of health-saving attitudes in the context of gender and age groups, %

19.5

19.3

28.6

25.2

9.1

21.0

7.2

24.7

30.5

8.5

8.1

21.5

6.7

Cluster 1. Responsible, but Cluster 2. Sharing responsibility,

Cluster 3. Responsible, motivated and caring for health

unmotivated, caring little or not carring motivated and caring for health for health

-

■ Men 18-30 y.o. ■ Men 30-60 y.o. Men 60+ y.o.

-

■ Women 18-30 y.o. ■ Women 30-55 y.o. ■ Women 55+ y.o.

Source: own compilation.

-

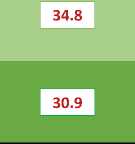

Figure 2. Population clusters by the nature of health-saving attitudes in the context of education level, %

26.2

25.9

34.8

13.1

33.1

33.7

27.3

5.8

Cluster 1. Responsible, but Cluster 2. Sharing responsibility,

unmotivated, caring little or not carring motivated and caring for health

for health

26.9

43.9

23.3

5.8

Cluster 3. Responsible, motivated and caring for health

■ Incomplete secondary, secondary

Secondary special ■ Secondary technical ■ Higher

Source: own compilation.

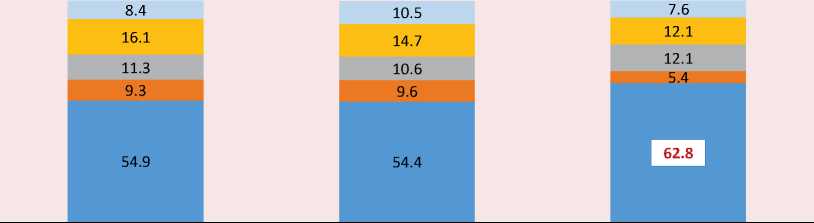

well as specialized secondary (35% vs. 27 in the second cluster and 23 in the third; Fig. 2 ). Among the representatives of the second cluster, there are significantly more people who have received higher education (33% vs. 26 in the first cluster and 27 in the third). The respondents of the third cluster are more likely to have a secondary technical education (44% vs. 26 in the first cluster and 34 in the second).

The analysis of cluster differentiation by marital and family status of respondents did not find statistically significant differences ( χ 2 = 13.310, p = 0.347). Nevertheless, attention is drawn to the fact of the predominance of those who are officially married among the representatives of the third cluster (63% against 55 in the first cluster and 54 in the second; Fig. 3 ). In many respects, the observed picture is explained by the age specifics of its contingent: almost a third of it consists of women of the middle age group (30–55 years), the vast majority of whom live in an official marriage union (65%).

Considering the differences between clusters by the level of income purchasing power, it is worth noting the following. In the first cluster, respondents are more likely to say that they have enough available money to purchase the necessary products and clothing, but larger purchases have to be postponed for later (53% vs. 49 in the second cluster and 46 in the third; Fig. 4 ). More than a third of the representatives of the third cluster are in a difficult financial situation when there is enough money only for the purchase of food (35% vs. 32 in the second and 30 in the first). In the second cluster, there are more respondents who most positively characterize their level of well-being: for them, there are no difficulties to purchase most durable goods or they do not deny themselves anything at all (15% vs. 10 in the first cluster and 13 in the third).

In addition, there is a pronounced differentiation of clusters by the territory of residence of the respondents who are part of them. For instance, among the representatives of the first

Figure 3. Population clusters by the nature of health-saving attitudes in the context of marital and family status, %

Cluster 1. Responsible, but Cluster 2. Sharing responsibility, Cluster 3. Responsible, motivated and unmotivated, caring little or not carring motivated and caring for health caring for health for health

Widowed

-

■ Unmarried (single)

-

■ Divorsed

-

■ In an unregistrated marriage, but live with a partner

-

■ In a registrated marriage

Source: own compilation.

-

Figure 4. Population clusters by the nature of health-saving attitudes in the context of the purchasing power of income, %

5.9

30.0

31.8

5.8

34.5 ]

52.8

7.7

48.9

11.4

46.2

12.1

Cluster 1. Responsible, but unmotivated, caring little or not carring for health

Cluster 2. Sharing responsibility, Cluster 3. Responsible, motivated and motivated and caring for health caring for health

-

■ There is not enough money even for the purchase of food, you have to get into debt

-

■ There is enough money only for the purchase of food

-

■ There is enough money to purchase the necessary products and clothing, but larger purchases have to be postponed for later

-

■ There is no difficulties to purchasemost durable goods (refrigerator, TV), but the purchase of a car is currently unavailable

-

■ There is enough money to deny yourself nothing

Source: own compilation.

-

Figure 5. Population clusters by the nature of health-saving attitudes in the context of the territory of respondents’ residence, %

19.5

33.7

22.0

21.8

22.5

14.8

38.2

19.7

17.9

24.2

Cluster 1. Responsible, but Cluster 2. Sharing responsibility,

unmotivated, caring little or not carring motivated and caring for health

for health

Cluster 3. Responsible, motivated and caring for health

-

■ Vologda

-

■ Cherepovets

-

■ Urban areas of districts

-

■ Rural areas of districts

-

Source: own compilation.

cluster there are more residents of district cities of the region (22% vs. 15 in the second cluster and 20 in the third; Fig. 5 ). The majority of respondents of the second cluster are the population of large cities (66% vs. 44 in the first cluster and 42 in the third), in particular, the regional center – Vologda (31% vs. 22 in the first and 23 in the third) and the industrial center – Cherepovets (35% vs. 22 and 18). Respondents from rural areas of municipal districts of the region are significantly more likely to be a part of the third cluster (38% vs. 34 in the first cluster and 20 in the second). The transfer of responsibility for health to medical workers by representatives of the second cluster, most of whom are the population of large cities, may be due to higher requests of citizens to the health care system [3, p. 138].

Attitudes toward health care are an important driving force for implementation of healthsaving practices. According to the analysis, the representatives of the third cluster are the most active in all healthy lifestyle practices: they are much more likely to give up smoking (57% vs. 44 in the second and 22 in the first clusters), visit the bath, sauna (51% vs. 26 and 16), seek medical help in a timely manner (47% vs. 44 and 15), walk (46% vs. 24 and 13), take care of the quality of drinking water (41% vs. 27 and 11), observe the regime and keep a diet (34% vs. 28 and 10), etc. (Tab. 5). In turn, all health-saving measures are the least popular among the respondents of the first cluster, among whom the proportion of those who do nothing to preserve and strengthen their own health is the largest (54% vs. 18 in the second and 12 in the first cluster). In many respects, the observed picture is explained by gender differences in attitudes toward health: among male population of the region, compared with female, the proportion of those who refuse any measures to preserve and strengthen is significantly higher (37% vs. 25). And more than half of the representatives of the first cluster are men (56%).

Table 5. Prevalence of healthy lifestyle practices in clusters by the nature of health-saving attitudes, %

Discussion of the results

The obtained results of the study, in particular, the socio-demographic features of health-saving attitudes of population, largely echo the data of other Russian studies. For example, a lower motivation to take care of health in men compared to women is previously confirmed in the works of I.B. Nazarova [38], L.Yu. Ivanova [39], I.P. Popova [40], S.S. Gordeeva [41], N.I. Pautova and I.S. Pautov [42]. The fact of improving the characteristics of caring for their own health as the education level increases is proved in the works of A.A. Kovaleva [12], A.A. Vyalshina [43], S.A. Vangorodskoy [6] and others. The relationship between living standards and attitudes toward health has been justified in many works. For example, as the study of S.A. Vangorodskaya has showed, as the well-being increases, the respondents’ interest in their health increases, its value in the rating of value dispositions increases [6].

However, some of the identified patterns do not correlate with the previously obtained conclusions. For example, the works of I.B. Nazarova [38], I.S. Pautov [44] prove a less active position of rural population in relation to their health compared to urban residents which is associated with lower availability of medical services, physical education and sports facilities in rural areas. While the most responsible position in relation to their own health in our study is demonstrated, on the contrary, not by urban, but by rural residents.

Despite the fact that Russian scientists A.I. Antonov and V.M. Medkov [45], A.I. Kuzmin [46], A.B. Sinelnikov [47], P.M. Kozyreva and A.I. Smirnov [48] confirmed the positive influence of family status (official marriage) on health attitudes, in our case this pattern is not found. The observed discrepancies indicate both the regional specifics of self-preservation attitudes of population, and the need for a more detailed study of their differences at the individual level.

The conducted research contributes to the development of both fundamental and applied science. Its theoretical significance lies in the generalization of approaches to the interpretation of health-saving motivation and its content, to the allocation of its structural components (health care degree, motivation nature, responsibility for health). The practical significance and scientific novelty are concentrated in population typology according to the characteristics of health-saving motivation which is especially important for understanding the behavioral patterns of population in relation to their own health and, as a result, for finding tools for managing them.

Conclusion

The cluster analysis, conducted on the data of a sociological survey of the Vologda Oblast residents, revealed three types of population by the nature of health-saving attitudes: responsible, but unmotivated, caring little or not caring for health; sharing responsibility, motivated and caring for health and responsible, motivated and caring for health. Based on the results of the consideration of the gender, age, educational, territorial and other parameters of the clusters, a socio-demographic portrait is determined for each of them:

-

1 cluster “Responsible, but unmotivated, caring little or not caring for health” is mainly middle-aged or older men living in the districts of the region (more often in district cities), having incomplete secondary, secondary or secondary special education, more often describing their well-being as “available funds are sufficient to purchase the necessary products and clothing, but larger purchases have to be postponed for later”.

-

2 cluster “Sharing responsibility, motivated and caring for health” is mainly women 55 years and older, residents of large cities (Vologda and Cherepovets), with higher education, more often highly evaluating their well-being level.

-

3 cluster “Responsible, motivated and caring for health” is mainly middle-aged women (30–55 years old) living in rural areas of the region, with secondary technical education, more often noting that they only have enough money to buy food.

In addition, the study allowed establishing that representatives of the third cluster are more committed to a healthy lifestyle – among them, all self-preservation practices (giving up bad habits, proper nutrition, physical and medical activity, etc.) are most widespread, while more than half of the respondents of the first cluster do not take any measures regarding their own health. Based on this, we can conclude that personal responsibility for one’s own health, expressed concern for the condition, orientation to a wide range of health-saving motives contribute to the greatest involvement of population in the practice of healthy lifestyle, while low motivation to take care of health or its absence, on the contrary, is more likely to contribute to the rejection of any self-preservation measures.

The results of the study help to better understand the types of health-saving attitudes that have developed in population, to assess their impact on adherence to a healthy lifestyle which is of great practical importance for managing selfpreservation behavior, in particular for determining behavioral risk groups of population, as well as adjusting health attitudes. So, for example, forfirst cluster representatives (responsible, but unmotivated, caring little or not caring for health), it becomes fundamentally important to purposefully stimulate motivation to lead a healthy lifestyle, increase awareness in various areas of knowledge about health care (about behavioral risk factors including bad habits, and their impact on health; about ways to overcome risk factors and “improve” lifestyle; about a variety of healthsaving practices). Work with representatives of the second cluster (sharing responsibility, motivated and caring for health) should be focused on increasing personal responsibility for health and fundamental importance of health by informing about the complex nature of the impact of its condition on all aspects of human life. For representatives of the third cluster (responsible, motivated and caring for health), it is important to maintain a high motivation level to take care of health. However, their more vulnerable financial situation compared to others poses a threat to the preservation of positive health-saving attitudes.

Despite the increased attention of the state to the issue of stimulating population to lead a healthy lifestyle, the established approach in state policy focuses mainly on the personal behavior of a person, often without taking into account their social context (level and living conditions). As a result, as N.S. Grigorieva and T.V. Chubarova note, there is an imbalance in the political strategies of the state and personal strategies of citizens. Even if a person is aware of the need to change health behavior, he or she may not have the institutional capacity to do so. For example, low incomes do not allow using the services of paid sports complexes or buying top-quality products, etc. [30, p. 203]. Thus, an important condition for the successful implementation of the policy of motivation for a healthy lifestyle should be the solution of the problem of insufficient level and quality of life of citizens.

Список литературы Health-saving attitudes as a factor promoting self-preservation behavior: approaches to the study and experience in typology

- Sabgaida T.P., Sergievskaya A.L. Determinants of relationships to preservation of their health of successful students. Sotsial'nye aspekty zdorov’ya naseleniya=Social Aspects of Population Health, 2011, no. 4(20). Available at: http://vestnik.mednet.ru/content/view/331/30/ (in Russian).

- Zhuravleva I.V. Why is the health of citizens of the Russian Federation not improving? Vestnik Instituta sociologii RAN=Bulletin of the Institute of Sociology RAS, 2012, no. 6, pp. 163–176 (in Russian).

- Zhuravleva I.V. Otnoshenie k zdorov’yu individa i obshchestva [Attitude to Health of the Individual and Society]. Moscow: Izd. Nauka, 2006. 238 p.

- Karaseva T.V., Ruzhenskaya E.V. The characteristics of motivation to follow healthy lifestyle. Problemy sotsial'noi gigieny, zdravookhraneniya i istorii meditsiny=Problems of Social Hygiene, Public Health and History of Medicine, 2013, no. 5, pp. 23–24 (in Russian).

- Shushunova T.N. Samosokhranitel'noe povedenie studencheskoi molodezhi: sotsiologicheskii analiz (na primere minskikh vuzov): monografiya. [Self-Preservation Behavior of College Youth: Sociological Analysis (the Case of Minsk College Students): monograph]. Minsk: Pravo i Ekonomika, 2010. 114 p.

- Vangorodskaya S.A. The factors of self-preservation behavior of the population in the region (based on empirical studies). Nauchnyi rezul’tat. Sotsiologiya i upravlenie=Research Result. Sociology and Management, 2018, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 13–26. DOI: 10.18413/2408-9338-2018-4-2-0-2 (in Russian).

- Cockerham W., Abel T., Lüschen G., Weber M. Formal rationality and health lifestyles. The Sociological Quarterly, 1993, vol. 34(3), pp. 413–428.

- Ivanovich Y., Matteson M. Promoting the individual’s health and well being. In: Causes, Coping and Consequences of Street at Work. Chichester etc.: Wiley, 1989. Pp. 267–299.

- Zhuravleva I.V., Shilova L.S., Kogan V.Z., Kopina O.S. Otnoshenie naseleniya k zdorov'yu: monografiya [The attitude of the population to health: Monograph]. Moscow: Institut sotsiologii RAN, 1993. 178 p.

- Rusinova N.L., Brown J. Social inequality and health in St. Petersburg: Responsibility and control over health. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsial'noi antropologii= The Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 1999, no. 1, pp. 103–114 (in Russian).

- Maksimova T.M. Sotsial’nyi gradient v formirovanii zdorov'ya naseleniya [Social gradient in the formation of public health]. Moscow: PER SE, 2005. 240 p.

- Kovaleva A.A. Self-care behavior in the system of health affecting factors. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsial'noi antropologii=The Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 2008, vol. XI, no, 2, pp. 179–191 (in Russian).

- Zhuravleva I.V., Ivanova L.Yu., Ivakhnenko G.A. Students: behavioral risks and value orientations in relation to health. Vestnik Instituta sotsiologii RAN=Bulletin of the Institute of Sociology, 2012, no. 6, pp. 112–129 (in Russian).

- Zhuravlev A.L., Zhalagina T.A., Zhuravleva E.A., Korotkina E.D. (Eds.). Sub”ekt truda i organizatsionnaya sreda: problemy vzaimodeistviya v usloviyakh globalizatsii: monografiya [The Subject of Labor and the Organizational Environment: Problems of Interaction in Globalization Conditions: Monograph]. Tver: Tver. gos. un-t, 2019. 340 p.

- Berezovskaya R.A. Attitude toward health research: the current state of the problem in Russian psychology. Vestniki Sankt-Peterburgskogo universiteta. Ser. 12. Psikhologiya. Sotsiologiya. Pedagogika=Vestnik of Saint-Petersburg University. Series 12. Psychology. Sociology. Pedagogy, 2011, no. 1, pp. 221–226 (in Russian).

- Becker A., Rosenstock I. Compliance with medical advice. Health Care and Human Behavior, 1984. Pр. 175–208.

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1980. 278 p.

- Maslow А. Po napravleniyu k psikhologii bytiya [Toward a Psychology of Being]. Moscow: EKSMO-Press, 2002. 270 p.

- Bodaleva A.A. Myasishchev V.N. (Eds.). Psikhologicheskie otnosheniya: izbrannye psikhologicheskie trudy [Psychological Relations: Selected Works on Psychology]. Moscow: Izd. Voronezh, 1995. 356 p.

- Yakovleva N.V. The study of individual differences in health-activity of the person. Eksperimental’naya psikhologiya=Experimental Psychology (Russia), 2015, vol. 8, vol. 3, pp. 202−214 (in Russian).

- Yakovleva N.V. Health-human behavior: Socio-psychological discourse. Lichnost’ v menyayushchemsya mire: zdorov’e, adaptatsiya, razvitie: elektronnyi nauchnyi zhurnal=Personality in a Changing World: Health, Adaptation, Development, 2013, no. 3. Available at: http://humjournal.rzgmu.ru/en/art?id=50 (in Russian).

- Yakovleva N.V., Faustova A.G., Frolov A.I. Psycologichal approaches to researching of the motivation healthy lifestyle. Lichnost’ v menyayushchemsya mire: zdorov’e, adaptatsiya, razvitie: elektronnyi nauchnyi zhurnal=Personality in a Changing World: Health, Adaptation, Development, 2014, no. 2(5). Available at: http://humjournal.rzgmu.ru/art&id=77 (in Russian).

- Korolenko A.V. Patterns of population’s self-preservation behavior: research approaches and building experience. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2018, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 248–263. DOI: 10.15838/esc.2018.3.57.16 (in Russian).

- Nazarova I.B. Zdorov’e zanyatogo naseleniya [Health of the Employed Population]. Moscow: MAKS Press, 2007. 526 p.

- Shabunova A.A. Zdorov’e naseleniya v Rossii: sostoyanie i dinamika: monografiya [Public Health in Russia: State and Dynamics: Monograph]. Vologda: ISERT RAN, 2010. 408 p.

- Shabunova A.A., Shuhatovich V.R., Korchagina P.S. Health saving activity as a health-promoting factor: the gender aspect. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2013, no. 3(27), pp. 123−132 (in Russian).

- Kalachikova O.N., Korchagina P.S. Main trends in self-preservation behavior of region’s population. Problemy razvitiya territorii=Problems Of Territory’s Development, 2012, no. 5(61), pp. 72–82 (in Russian).

- Revyakin E.S. Self-preservation behavior: Idea and essence. Vestnik IGEU=Vestnik of Ivanovo State Power Engineering University, 2006, issue. 1, pp. 1–4 (in Russian).

- Zhuravleva I.V., Lakomova N.V. Social conditionality of adolescent health in a temporary aspect. Sotsiologicheskaya nauka i sotsial'naya praktika =Sociological Science and Social Practice, 2019, no. 2(26), pp. 133–152. DOI: 10.19181/snsp.2019.7.2.6414 (in Russian).

- Grigor’eva N.S., Chubarova T.V. Motivation in the state regulation system (in the case of the formation of a healthy lifestyle). Gosudarstvennoe upravlenie. Elektronnyi vestnik=Public-administration. E-Journal, 2018, no. 70, pp. 194–219 (in Russian).

- De Vries H., Van’t Riet J., Spigt M., Metsemakers J., Van den Akker M., Vermunt J.K., Kremers S. Clusters of lifestyle behaviors: Results from the Dutch SMILE study. Preventive Medicine, 2008, vol. 46 (3), pp. 203–208. DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.005

- Chan C.W., Leung S.F. Lifestyle health behavior of Hong Kong Chinese: Results of a cluster analysis. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 2015, vol. 27 (3), pp. 293−302. DOI: 10.1177/1010539514555214

- A.V. Zelionko, V.S. Luchkevich, V.N. Filatov, I.A. Mishkich. Formation of risk groups on the level of hygiene awareness and motivation to health-saving behavior among urban and rural residents. Gigiena i sanitariya=Hygiene and Sanitation (Russian Journal), 2017, vol. 96, no. 4, pp. 313–319. DOI: 10.47470/0016-9900-2017-96-4-313-319 (in Russian).

- Ammosova E.P., Klimova T.M., Zakharova R.N., Fedorov A.I., Baltakhinova M.E., Gavril’eva L.A. Social factors and value-motivational indicators of health saving behavior of rural residents of Yakutia. Sibirskii meditsinskii zhurnal=Siberian Medical Journal (Irkutsk), 2019, vol. 157, no. 2, pp. 50–54 (in Russian).

- Vasil’eva N.M., Petrash M.D. Socio-psychological determinants of self-preservation behavior of medical personnel at the initial stages of professional activity. Nauchnye issledovaniya vypusknikov fakul’teta psikhologii SPbGU=Scientific research of graduates of the Faculty of Psychology of St. Petersburg State University, 2013, no. 1(1), pp. 48–55 (in Russian).

- Ryazanova E.A. To the problem of typology of the riskogenic behavior (analysis on the example of an industrial enterprise of Perm region). Analiz riska zdorov’yu=Health risk analysis, 2016, no. 2, pp. 68–75 (in Russian).

- Roshchina Ya.M. Health-Related Lifestyle: Does Social Inequality Matter? Ekonomicheskaya sotsiologiya=Journal of Economic Sociology, 2016, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 13–36 (in Russian).

- Nazarova I.B. Russia’s population health: Factors and characteristics in the 1990’s. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 2003, no. 11, pp. 57–69 (in Russian).

- Ivanova L.Yu. Self-preservation behavior and its gender characteristics. In: Drobizheva L.M. (Ed.). Rossiya reformiruyushchayasya: ezhegodnik [Russia is Being Reformed: Yearbook]. Moscow: Institut sotsiologii RAN, 2006. Pp. 110–133 (in Russian).

- Popova I.P. Health behavior and financial situation: gender aspects (based on the data of a longitudinal survey). Zdravookhranenie Rossiiskoi Federatsii=Health Care of the Russian Federation, 2007, no. 1, pp. 47–49 (in Russian).

- Gordeeva S.S. Gender differences in attitude to health: a sociological aspect. Vestnik Permskogo universiteta=Bulletin of Perm University, 2010, issue 2(2), pp. 113–120 (in Russian).

- Pautova N.I., Pautov I.S. Gender characteristics of health self-assessment and perception as a socio-cultural value (based on the data of the 21st round of RLMS-HSE). Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve=Woman in Russian Society, 2015, no. 2(75), pp. 60–75 (in Russian).

- Vyal’shina A.A. Influence of the level of education on the health of the rural population. Sotsial’nye aspekty zdorov'ya naseleniya=Social aspects of public health, no. 1(66), 2020. Available at: http://vestnik.mednet.ru/content/view/1133/30/lang,ru/ DOI: 10.21045/2071-5021-2020-66-1-6 (in Russian).

- Pautov I.S. Analysis of the relationships between self-assessment of health, social practices that affect health, and the type of settlement in the case of modern Russia. Zdorov’e – osnova chelovecheskogo potentsiala: problemy i puti ikh resheniya=Health is the basis of human potential: problems and ways to solve them, 2015, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 93–99 (in Russian).

- Antonov A.I., Medkov V.M. Vtoroi rebenok [The second Child]. Moscow: Mysl’, 1987. 299 p.

- Kuz’min A.I. Sem’ya na Urale (demograficheskie aspekty vybora zhiznennogo puti) [Family in the Urals (Demographic Aspects of Choosing a Life Path)]. Ekaterinburg: Nauka: Ural. izd. firma, 1993. 235 p.

- Sinel’nikov A.B. Influence of family and demographic status on health and self-evaluation of health. Sotsial’nye aspekty zdorov'ya naseleniya=Social aspects of public health, 2012, no. 6(28). Available at: http://vestnik.mednet.ru/content/view/443/30/lang,ru/

- Kozyreva P.M., Smirnov A.I. Russian citizens’ health self-assessment dynamics: Relevant trends of the post-soviet era. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 2020, no. 4, pp. 70–81. DOI: 10.31857/S013216250009116-0