Impact of Foreign Language Proficiency and English Uses on Intercultural Sensitivity

Автор: Jia-Fen Wu

Журнал: International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science (IJMECS) @ijmecs

Статья в выпуске: 8 vol.8, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The main purpose of this study was to examine the impact of English uses and English proficiency on inter-cultural sensitivity among 292 Taiwanese participants. Results indicate that there is a significant differential level of English uses across three groups of the participants (high, moderate and low frequency of English uses). Post-hoc comparison indicated that high-frequency English usesrs have significantly higher inter-cultural sensitivity than moderate and low-frequency users. However, the results do not support the hypothesized linkage between foreign language proficiency and inter-cultural sensitivity. The implications from these findings suggest that the frequency of English uses will better equip EFL learners with sufficient socio-linguistic competences and communicative skills compared with English proficiency. Moreover, inter-cultural sensitivity is a skill learned through authentic interaction in an intercultural context. Thus, the MOF in Taiwan should rethink of washback effect of the English Benchmark Policy.

English proficiency, Frequency of English uses, Foreign language proficiency, intercultural sensitivity, socio-linguistic competences

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15014891

IDR: 15014891

Текст научной статьи Impact of Foreign Language Proficiency and English Uses on Intercultural Sensitivity

Published Online August 2016 in MECS DOI: 10.5815/ijmecs.2016.08.04

-

I. I ntroduction

Being a global citizen is a goal for everyone in the world. Remiers (2008, 2009) proposed three

characteristics for a globally competent person who has 1) global understanding: substantive knowledge of world issues and a capacity to communicate successfully within the boundary of the global village, 2) inter-cultural sensitivity: adequate adjustment toward cultural differences, and 3) foreign language proficiency: a capacity to speak and understand a foreign language. In addition to inter-cultural communication competence (ICC), internationalization initiatives suggest that developing foreign language proficiency is necessary to address the needs of a globalizing market and economy (Altbach & Knight, 2007; CIA, 2010; Panetta, 1999). Scholars of inter-cultural competence also assert that foreign language proficiency, especially English proficiency, is crucial to developing inter-cultural competence (Deardorff, 2006). That is, the higher the foreign language proficiency, the greater the inter-cultural communication competence.

Although inter-cultural sensitivity and foreign language proficiency are both regarded as essential for a globally competent person, the controversy on their relationship has existed for years. There is a lack of empirical evidence supporting the notion that foreign language proficiency plays a role in cultivating inter-cultural competence. Evidence from an empirical study are likely to answer questions such as whether an individual’s foreign language proficiency would influence his/ her level of inter-cultural sensitivity (or competence), to what extent foreign language proficiency would influence inter-cultural sensitivity, and if there is a positive correlation between foreign language proficiency and inter-cultural sensitivity.

In order to clarify the relationship between inter-cultural sensitivity and English proficiency and English uses, this study aims to examine the following questions:

RQ 1. How frequency of English uses impacts on inter-cultural sensitivity among 292 Taiwanese participants?

RQ 2. How English proficiency impacts on inter-cultural sensitivity among 292 Taiwanese participants?

-

A. Conceptualizing Inter-cultural sensitivity

Inter-cultural sensitivity, a vital ability for people living in a pluralistic democratic society (Tamam, 2010), is regarded as a multi-dimensional construct and a prerequisite for achieving inter-cultural competence (Chen and Starosta, 2000; Hammer, Bennet and Wiseman,

2003). Situated in an inter-cultural environment, an individual’s sensitivity toward cultural differences and similarities will make him/her think and act adequately as an inter-cultural speaker.

Second, in contrast, Bennett (1986, 1993) defined inter-cultural sensitivity as a developmental process of acculturation. During the process of acculturation, as Bhawuk and Brishlin (1992) stated, ‘To be effective in other cultures, people must be interested in other cultures, be sensitive enough to notice cultural differences and also be willing to modify their behavior as an indication of respect for people of other cultures. A reasonable term that summarizes these qualities of people is inter-cultural sensitivity (p.416).’ Accordingly, an individual should gradually become inter-culturally sensitive.

Since Inter-cultural sensitivity is objectively measurable, the different theoretical frameworks were provided. Defined by Bennett’s Developmental Model of Inter-cultural Sensitivity (DMIS, Bennett, 1998), the six developmental stages to provide a theoretical framework for assessing inter-cultural sensitivity administered in cross-cultural adaptation, from Denial, Defense, Minimization, Acceptance, Adaptation, and Integration, which were categorized into two phases to demonstrate a continuum from ethno-centric to ethno-relative. Theoretically grounded in the DMIS, the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) (Hammer and Bennett, 2002) developed in 1998 is an assessment tool to determine the relative intercultural sensitivity of individuals and represents ‘a theoretically grounded measure of this capability toward observing cultural differences and commonalities and modifying behavior to cultural context’ (Hammer, 2011, p. 475). Based on the continued research, IDI v2 was developed in 2003; and IDI v3 is currently available (Hammer, 2011). IDI v3 contains 50 items (both online and paper-and-pencil) and can be completed in 15-20 minutes. Scholars used IDI to investigate how the individuals reinforced in an inter-cultural environment transform themselves from the ethno-centric stage to the ethno-relative stage overtime (Engle & Engle, 2004;

Chen and Starosta’s (2000) Inter-cultural Sensitivity Scale gauges inter-cultural sensitivity in general and presents five factors of inter-cultural sensitivity: Interaction Engagement, Respect for Cultural Differences, Interaction Confidence, Interaction Enjoyment, and Interaction Attentiveness. Compared with the IDI, Chen and Starosta’s scale has been broadly employed in Asian countries such as China, Thailand, Hong Kong, Korea, Iran , and Taiwan, and it is , therefore , more applicable in the context of this present study. Recently, Asian scholars tried to formulate an adaptive ISS for the populations in their native countries by examining and modifying the original ISS. For example, Tamam (2010) examined Chen and Starosta’s ISS (2000) and formed a customized version of ISS for Malaysians. A published article validating Chen and Starosta’s ISS to propose s a modified version of ISS, 13-item inter-cultural sensitivity scale, was proved to be satisfying and reliable (Wu, 2015).

Based on the statements above, Inter-cultural sensitivity has been defined by many scholars from different theoretical perspectives. According to Bennett’s DMIS, the individuals may establish an ethno-relative identity and enjoy the cultural differences in the integration stage. The interculturally-sensitive individuals are able to present emotions and respond positively and adequately before, during, and after interaction, which would lead to a high degree of satisfaction to help them ‘achieve an adequate social orientation that enables them to understand their own and their counterparts’ feelings and behaviors’ (Chen, 2010, p.2). Similarity, Chen and Starosta’s description on Inter-cultural sensitivity, the affective aspect of inter-cultural communicative competence, can be defined as an important ability ‘to function effectively in an environment depends upon our skill in recognizing and appropriately to the values and expectations of those around us’ (Anderson, Lawton, Rexeisen, and Hubard, 2006, p.459). In brief, the positive emotion produced by inter-cultural sensitivity yields an individual’s willingness to respect and appreciate cultural differences during intercultural interaction (Bhawuk & Brislin, 1992; Chen, 2005).

-

B. Linking Inter-cultural Sensitivity to English

proficiency

The relationship between Language and Culture was seen as ‘intertwined’, ‘reciprocal’, ‘inseparable’, ‘inextricably connected (Liddicoat, Papademetre, Scarino, 2003).’ Scholars believe that ‘Learning a foreign language enables learners to understand a culture, world view, and unique way of life that differ from their own, helping reduce ethno-centrism and stereotypes (Byram, Esarte-Sarries, Nichols, Stevens, and Osborn, 2000, as cited in Kubota, 2003, p.12).’ The notion ‘culture and language are in-separate’ is based on assumption that learning a language involves assimilating learners to a person from the culture where they speak the target language (Jeon and Lee, 2012).

Therefore, foreign language ability is regarded as a variable , promoting inter-cultural sensitivity. Some scholars conducted empirical studies to investigate the relationship between foreign/ English language proficiency and inter-cultural sensitivity. Issues on number of foreign languages learned and levels of foreign language proficiency are discussed in relevant studies. After conducting extensive survey on factors related to inter-cultural sensitivity, Olson and Kroeger (2001), Sizoo, Iskat, Plank, and Serrie (2004), and Vilà (2006) concluded that the ability to speak a second language (or several languages) promotes increased inter-cultural sensitivity. Ruokonen and Kairavuori (2012) found that students learning a second/foreign language chose to behave in more ethno-relativistic ways than did monolingual students. The data showed that they appeared to be more sensitive to cultural differences. Furthermore, the more foreign languages they can speak, the higher their score on inter-cultural sensitivity.

Olson and Kroeger (2001) surveyed the inter-cultural sensitivity of 52 university faculty and staff in nonEnglish speaking countries and found that the higher their foreign language proficiency (a language other than English) the greater their inter-cultural sensitivity was. Corbaz (2006) conducted an experimental study and found the effect of foreign immersion programs on inter-cultural sensitivity toward other cultures. Although it was a small-scale research, time of exposure to the foreign language environment might have influenced inter-cultural sensitivity. Peng’s (2006) study suggests that in certain ways English proficiency affects inter-cultural sensitivity, and foreign language proficiency can effectively predict inter-cultural sensitivity. However, Peng did not test the participants’ English proficiency in his study. In non-English speaking countries, such as Taiwan, English learned as a foreign language is considered as the most influential language both in and out of the nation. The results of Yuan’s (2009) study indicated that those English majors with higher English proficiency had greater inter-cultural sensitivity, demonstrated better observation of their interlocutors , and responded more appropriately in the inter-cultural surroundings, compared to those with lower English proficiency. Using Chen and Starosta’s (2000) Inter-cultural Sensitivity Scale, Rahimi and Soltanis’s (2011) investigated the correlation between English language proficiency (TOEFL scores in that study) and inter-cultural sensitivity among 36 Iranian EFL senior learners. The results showed a significant relationship between the students’ English language proficiency and inter-cultural sensitivity (r= .775, p= .000).

Opposing views on the significance of the relationship between foreign language ability and inter-cultural sensitivity do exist. Liddicoat, Papademetre, Scarino, and Kohler (2003) criticize the DMIS proposed by Bennett, Bennett, and Allen (2003), on the basis that it fails to link inter-cultural sensitivity and foreign language proficiency adequately. They also claim that the hypothesized linkage between foreign language proficiency and the DMIS is deficient without considering the prior starting point of exposure to inter-cultural differences. Chen (2008) found no significant and direct link between foreign language ability and individuals’ inter-cultural sensitivity. Adamson and O’Donnell (2008) compared the differences in inter-cultural sensitivity between Japanese and American college students. Unlike their American counterparts, the Japanese students were required to learn one more foreign language, take a foreign language proficiency test, and study abroad at least one time in their experimental study. At the end of the study, the results showed both Japanese and American students exhibited low inter-cultural sensitivity and no significant difference existed between them. Adamson and O’Donnell (2008) concluded that ‘a person’s foreign language ability and time spent abroad were not signifiers of inter-cultural sensitivity, which points to the notion that inter-cultural sensitivity is a skill that must be learned, indicated by each sample’s low sensitivity score’ (p.13). Findings of Jackson’s (2011) study showed that participants had an advanced level of academic proficiency in the host language when entering his study abroad program. However, the inter-cultural sensitivity of most lagged far behind. Jackson’s findings have reinforced the observation of some applied linguists, such as Kramsch (1998), Byram (1997), and Park (2006), who disagree on the naïve assumption that inter-cultural competence will develop at the same rate as foreign language proficiency.

Using the ANOVA analysis, Ruokonen and Kairavuori’s (2012) recent research suggests that there is no significant difference in the level of inter-cultural sensitivity of university students based on their foreign languages abilities (F= 1.496, p=.217). Wu (2013) surveyed 87 adult participants and found that no significant correlation exists between English proficiency (TOEIC scores) and inter-cultural sensitivity.

Over the past decades, the correlation between foreign/ English language proficiency and inter-cultural sensitivity has been the subject of controversy.

In summary, foreign languages, especially English, did play a crucial role in inter-cultural communication; however, learning one foreign language or more does not seem to guarantee an increase in inter-cultural sensitivity. More doubt is cast on the assumption that the development of inter-cultural competence might be parallel with language proficiency.

-

C. Linking Inter-cultural Sensitivity to Frequency of English uses

Understanding the nature of the relationship between language and culture is central to the process of learning a foreign language. A language is not so much a thing to be studied, as a way of exploring, understanding and communicating about the world. Thus, a language learner will benefit from each time they use the second/foreign languages. Results of Wu’s (2013) study showed no significant correlation between foreign language proficiency and inter-cultural sensitivity; however, she found there is a significant correlation between inter-cultural sensitivity and frequency of talking with foreigners in English (r=.385, p=.000***), writing/ typing in English(r=.139, p=.010**), and number of foreign languages learned(r=.130, p=.016*). The findings suggest that the more frequently the participants talk to foreigners in English, so the greater the number of opportunities to interact with foreigners. Influenced by this inter-cultural interaction, subconsciously they are likely to improve their inter-cultural sensitivity. In addition, this finding supports the views held by McMurray (2007), Wu (2013a) and Lin (2011), who have stated that students who frequently speaking English outside class tend to demonstrate a higher level of inter-cultural sensitivity than those who did not.

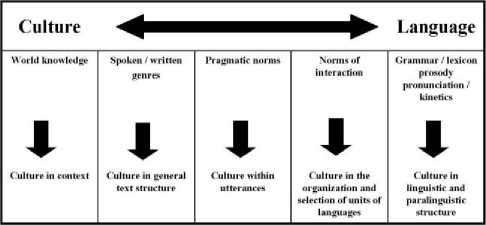

The above-mentioned statements reveal the fact that English uses, like foreign language proficiency, also play a crucial role in inter-cultural sensitivity. The more frequently the foreign language learners speak or write in English for communication, the greater inter-cultural sensitivity they will have. This was especially true where foreign language learners could not be exposed to academic discourse in formal classrooms and had little contact with native speakers of the target language outside their classrooms. Figure 1 shows how culture connects with the different aspects of language. From the far left end of this model to the other end, an individual begins by understanding the target culture and gradually becomes aware that ‘culture informs the way in which appropriate behaviors or speech act are accepted through spoken or written genres’ (Wu, 2013, p.19). This model implies that the higher one’s level of foreign language proficiency, the more inter-cultural communicative competence one can apprehend. To be more specific, based on Canale (1983), inter-cultural communicative competence comprises four parts: grammatical competence (i.e. knowledge of language code); socio-linguistic competence (i.e. knowledge of the sociocultural rules of use in a particular context); strategic competence (i.e. knowledge of how to use communication strategies to handle breakdowns in communication) , and discourse competence (i.e. knowledge of achieving coherence and cohesion in a spoken or written text).

Resource:Wu (2013, p.19)

Fig.1. Interacation between cultures and langusges

-

D. English proficiency policy in Taiwan.

Since globalization touches the lives of people everywhere and English has become the lingua franca of the 21st century, over 2 billion people are learning English. Accordingly, English has become nationally competitive because of globalization. This serves to emphasize the fact that the need for language learning is greater than ever.

In Taiwan, English is recognized as a global or international language, and has increased in importance as a result of business, trade, the economy, and tourism. Internationalization on college campuses has helped to make Taiwan a more multicultural society. Announced by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan, three programs Scholarships for Excellent Students to Study Abroad , Hardships for Students to Study Abroad , and Pilot Overseas Internships send recipients overseas to attend an institute or an enterprise to broaden their world vision. Those who apply to become exchange students overseas are required to take internationally recognized English proficiency tests, such as TOFEL or TOEIC, and fulfill the minimum requirements of the overseas institutes they are intending to study at before they are accredited. Also, the Undergraduate English Graduation Threshold or the English Benchmark Policy for Graduation announced by universities encourages Taiwanese students to take English proficiency tests in order to assure themselves that they are qualified to pass their school work. In the meantime, International Student Recruiting Policies in Taiwan attract more international students from overseas, thereby expanding college campus diversity.

English proficiency will never be the single factor for success in inter-cultural communication; yet, the internationalization in Taiwan apparently follows the beliefs that cultures and languages are inseparable, and that increasing individuals’ English proficiency will logically promote their inter-cultural sensitivity. Tsai

-

(2009) thus pointed out that the importance of cultural learning in EFL education is often ignored by the MOE and English teachers, concluding that English teachers in Taiwan need to perceive more about the essence of cultural learning and clarify if linguistic knowledge is the most important element in cross-cultural communication.

-

II. M ethods

For this study, quantitative methods were utilized as a time-effective way to solicit data. The questionnaires and Inter-cultural Sensitivity Scale were used to obtain the participants’ responses.

-

A. Sampling and Data Collection

The data are from a sample of 292 voluntary participants from the northern, central, and southern regions of Taiwan, 97 males and 195 females. The participants were selected as the target subjects because they were Taiwanese, learning English as a foreign language, and had all taken TOEIC. Self-administrated questionnaires were employed to gather data. The average age was 22.77 years, ranging from 17 to 49 years of age. The majority of them (78%) were college students, and 62 per cent were English majors. They were provided with sufficient information regarding the objectives of this study beforehand. They were all assured that they were voluntarily involved in this study and that their personal information would remain confidential.

-

B. Measurement

All participants answered four questions: ‘1) How frequently do you read in English? 2) How frequently do you speak to people of different ethnic groups in English? 3) How frequently do you chat with people of different ethnic groups in English? 4) How frequently do you write to people of different ethnic groups in English?’ Five-point response choices were given for each question: 1 = never, 2 = once a week, 3 = 1-2 day s per week, 4 = 3-5 days per week, and 5 = 6-7 days per week. Those four questions were employed to form an index of frequency of English uses for this present study.

Results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test indicated that the collected data was suitable for factor analysis (KMO = .721, p = .000). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was .721, exceeding 0.6, the recommended value (Field, 2005), and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance at the level of .000. The correlation matrix showed that multicollinearity was not a problem. Principal component analysis produced only one factor with internal consistency (α) of .77 and explained 51.60% variance. Composite scores on this index indicated levels of frequency of English uses. The higher mean score on the frequency of English uses index suggests greater English uses experience. The participants’ scores were divided into three groups according to mean scores (27%, 73%, and else, respectively) – low (n=89) moderate (n=70) high (n=133) –frequency of English uses.

Inter-cultural sensitivity was assessed using 13-item of Chen and Starosta’s (2000) inter-cultural sensitivity scale (Wu, 2015). The adapted version of the ISS scale comprised four interrelated factors: interaction confidence ( 4 items; α=.85), interaction engagement and attentiveness (3 items; α=.80), respect for cultural differences (3 items; α=.76), interaction enjoyment (3 items; α=.79). This adapted ISS demonstrated strong internal consistency with .801 reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α = .801). A five-point scale was utilized to respond to each item: 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = uncertain, 2 = disagree, 1 = strongly disagree. The contents of these items were associated with the participants’ feelings and attitudes about communicating and interacting with people from diverse cultural backgrounds. The higher score indicates a higher inter-cultural sensitivity. Scale examples of each factor are as follows:

Interaction Confidence : I feel confident when interacting with people from different cultures.

Interaction Engagement and Attentiveness : I am very observant when interacting with people from different cultures.

Respect for Cultural Differences : I am open-minded to people from different cultures.

Interaction Enjoyment : I get upset easily when interacting with people from different cultures.

The participants were also asked to state their TOEIC scores and the number of foreign languages learned. Their TOEIC scores were divided into three levels according to mean scores (27%, 73%, and else, respectively) – low (n=80) moderate (n=131) high (n=81).

-

III. R esults

Statistical results gathered were presented in this section. First, the profile of participants was described. Second, results of a zero-order correlation analysis were demonstrated. Last, results of the two-way analysis of variance were described.

-

A. Profile of Participants

First of all, the results of descriptive statistics presented in the sample consisted of 292 participants, 67 males and 225 females. The average age of the participants was 22.7 years, and they ranged from 17 to 49 years old. The majority of them were English majors (63.7%). Nearly 56.8% of them had learned two foreign languages, and 16.8% of them had learned three foreign languages. Only 6.5% of them had learned more than three foreign languages. All of the participants were required to submit their TOEIC scores for this study. Their average score on TOEIC was 634.74, ranging from 340 to 910.

-

B. Results of a zero-order correlation analysis

Second, a zero-order correlation analysis of the demographic variables with the independent and dependent variables were computed (see Table 1).

Pearson products-moment correlation coefficients among the variables indicated that none of the selected demographic was significantly correlated with inter-cultural sensitivity, except the number of foreign languages learned, was significantly correlated with inter-cultural sensitivity (.124*, p=.034). Frequency of English uses significantly correlated with inter-cultural sensitivity (.261**, p=.000), Interaction Engagement and Attentiveness (.316***, p=.000), Respect for cultural differences (.216***, p=.000), and Interaction Enjoyment (.160***, p=.006). TOEIC scores did not significantly correlate with inter-cultural sensitivity, but it significantly correlates with Interaction Engagement and Attentiveness (.146*, p=.013).

Table 1. Zero-order correlations among variables ст ст ст ст й ст"

(1)1шелкшпСоа5<1«1се ЙЗ 302" 343" 533~060

315 7»0 ЙЙ 300 313

1С:::^?!::!'?:: У ■■ ■•• ;•••. I - .423" 145' .630" .316".146’ and Attentiveness ООО 013 ООО ООО.013

(3)Respect for Cultural - ЗТГ УУ уГ ОЗб"

Differences ОГО ОГО ООО.538

(4)Interaction Enjoymmi " .608" .160".006

ОТО 006020”

(5)Inter-aiitural sensitivity - .261047

ООО 022"

(6)Frequency of English use - .269'"

ото"

(7)TOEIC scores

•*p<0.01 * p<0.05

-

C. Results of the two-way analysis of variance

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the probable influence in inter-cultural sensitivity across three levels of English uses frequency and three levels of TOEIC scores. A two-way between-group analysis was considered as the most adequate statistical method for the purpose (see Table 2). Non-significant results derived from the Leven’s Test of Equality of Error Variance suggested that the error variance of the dependent variable is equal across groups [F (8, 283) = 1.207, p= .295 ]. Thus, the two-way analysis of variance did not violate the homogeneity of variance assumption.

Table.2. Two-way ANOVA for frequency of English use and level of English proficiency

F .01 (8.283)=1.207 (p= 295) F 01 (8.283Н-П5*** (p= 001)

|

Sources |

df |

MS |

F |

p-value |

|

Frequency of English use |

1.438 |

8.045 |

.000*** |

|

|

Level of English Proficiency |

- |

.MS |

J66 |

.767 |

|

Frequency of English use 4 Level of English Proficiency |

4 |

.215 |

1.201 |

.310 |

|

Error |

283 |

.179 |

||

|

Total |

292 |

-

IV. D iscussion

The motivation of this study arose from the controversy regarding the relationships between English proficiency, the frequency of English uses, and inter-cultural sensitivity. Therefore, this study was carried out to investigate the impact of English proficiency and the frequency of English uses on inter-cultural sensitivity and attempted to resolve the controversy. According to the general guidelines provided by Cohen (1988), the results of a zero order-correlation analysis suggest that the frequency of English uses holds a weak correlation with Inter-cultural Sensitivity, with a significant correlation coefficient of .261(p=.000). The results also show the significant correlation between the frequency of English uses and Interaction Engagement and Attentiveness reached a medium correlation level, with a correlation coefficient of .316 (p=.000). On the contrary, no significant correlation is shown to exist between inter-cultural sensitivity and English proficiency, measured by TOEIC scores , in this study. This finding does not imply that English proficiency is not associated with inter-cultural sensitivity for English proficiency, to a certain extent, influences inter-cultural sensitivity.

Results of a two-way analysis of variance show that there was a significant main effect for the level of English frequency on inter-cultural sensitivity, whereas no significant main effect for TOEIC scores on inter-cultural sensitivity was found. There was no significant interaction effect for the differential level of TOEIC scores and differential level of English uses frequency on inter-cultural sensitivity. These findings have reinforced the results of a zero-correlation analysis and the notion that the development of inter-cultural sensitivity might be parallel language proficiency. Furthermore, results of a post hoc comparison across differential levels of English use frequency indicated that high frequency English users had significantly higher inter-cultural sensitivity than the moderate and low frequency English users. This supports some scholars’ argument that inter-cultural sensitivity will develop at the same rate as foreign language proficiency.

In the past decades, English proficiency was naturally hypothesized to have a significant and positive linear relationship with inter-cultural sensitivity. Foreign language proficiency, especially English proficiency in this study, merely represents linguistic knowledge (i.e. knowledge of code, grammar, lexicon, etc.) without socio-linguistic knowledge, which is a vital element for success in inter-cultural communication. The two analyses in this study emphasize the view that frequency of English uses is more strongly linked to promotion in inter-cultural sensitivity than English proficiency.

Several pedagogical implications can be drawn from this study.

RQ 1. How frequency of English uses impacts on inter-cultural sensitivity among 292 Taiwanese participants?

First, the findings underscore the importance of frequency of English uses. Even though the MOE in Taiwan provides college students with three programs Scholarships for Excellent Students to Study Abroad , Hardships for Students to Study Abroad , and Pilot Overseas Internships bring recipients overseas to broaden their vision, the minimum requirement of English proficiency (i.e. TOEFL or TOEIC scores) seems to be the major concern for the applicants.

As scholar of intercultural competence, Tsai (2009), argues, the goals of Taiwan’s foreign language education seem to assume that linguistic knowledge is the most important element in cross-cultural communication. With this approach, English language educators should emphasize authentic interaction and language use instead of just focusing on learning about foreign language. In fact, it is more appropriate to have the students maximize their preparedness in strengthening foreign language and training intercultural experience/ practice before they physically attend an overseas setting where they might encounter culture shock. This is especially so when those students need more experience that involves treating English language use, whether spoken or written, as opportunities to discover how language can be made meaningful while interacting with people of diverse cultures.

RQ 2. How English proficiency impacts on inter-cultural sensitivity among 292 Taiwanese participants?

Second, inter-cultural sensitivity does not develop at the same rate as foreign language proficiency, and as Adamson and O’Donnell (2008) suggest, ‘inter-cultural sensitivity is a skill that must be learned’ (p.13). In other words, an individual’s inter-cultural sensitivity should be cultivated gradually through authentic interaction, conversation, and shared understanding in an inter-cultural context. Native speakers' direct exposure to the target language is likely to be a more effective way to develop inter-cultural sensitivity, compared to indirect exposure such as books, movies, etc. As Tsai (2009) pointed out, the importance of cultural learning in the study of EFL is ignored by the MOE and English teachers, even though cultural learning is perceived as an essential element to developing students’ intercultural communicative competence. In Taiwan, the Undergraduate English Graduation Threshold or the English Benchmark Policy for Graduation in Taiwan's Universities has become a great subject matter for college students and overemphasis on these policies result in learning for English proficiency tests.

-

V. C onclusion

In conclusion, this study is a step in clarifying the controversy on the relationship between inter-cultural sensitivity and English proficiency. Nevertheless, proving the impact of frequency of English uses on inter-cultural sensitivity, the design of the present study is not without limitations. First, this present study was carried out in Taiwan with participants who had taken TOEIC. Thus, the applicability of the results to other populations with different education backgrounds may be limited. A comparative study should be replicated to detect differences between ethnic Chinese and people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Although the results of a zero-order correlation analysis show a weak correlation between inter-cultural sensitivity and the frequency of English uses, the design of the questionnaires used, which were subject to constant revision and changes, could be improved for future studies.

A cknowledgment

My special thanks are extended to Dr. Ming-Lung Wu, Department of Education, Kaohsiung Normal University, for her valuable advice in the statistical analysis. I am thankful to Mr. Mark Yeats, Department of Applied Foreign Language, Takming University, for his encouragement and also for his flawless grammatical editing of my thesis.

Список литературы Impact of Foreign Language Proficiency and English Uses on Intercultural Sensitivity

- Altbach, P. G., & Knight, J. (2007). The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3-4), 290-305.

- Baxter Magolda, M. B. & King, P. M. (2005). A developmental model of inter-cultural maturity. Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 571-592.

- Bennett, J., Bennett, M., & Allen, W. (2003). Developing inter-cultural competence in the language classroom. In D. Lange, & M. Paige (Eds.), Culture as the Core: Perspectives on Culture in Second Language Learning (pp. 237-270). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Byram, M., & Guilherme, M. (2000). Human rights, cultures and language teaching. A. Osler Citizenship and Democracy in Schools: Diversity, Identity, Equality. Stokeon-Trent: Trentham Books.

- Engle, L., & Engle, J. (2004). Assessing language acquisition and inter-cultural sensitivity development in relation to study abroad program design. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, X, 219-236.

- Chi, E. (2007). Validating the scale of global citizenship and examining the related variables. Journal of Educational Evaluation, 20(2), 151-172.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Crozet, C., & Liddicoat, A.J. (1999). The challenge of inter-cultural language teaching: Engaging with culture in the classroom. J. Lo Bianco, A.J. Liddicoat & C. Crozet (eds), Striving for the Third Place: Inter-cultural competence through language education (pp. 113-126). Canberra: Language Australia.

- Crozet, C. (2003). 'A conceptual framework to help teachers identify where culture is located in language use', in Joseph Lo Bianco and Chantal Crozet (ed.), Teaching Invisible Culture: Classroom Practice and Theory, Language Australia, Melbourne, pp. 39-49.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of inter-cultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241-266. doi: 10.1177/1028315306287002

- Field, A. P. (2005). Discovering Statistics using SPSS. London: Sage.

- Hammer, M., & Bennett, M. (2002). The Intercultural Development Inventory: Manual. Portland, OR: Intercultural Communication Institute.

- Hammera, M. R. (2011). Additional cross-cultural validity testing of the Intercultural Development Inventory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 474-487.

- Hammer, M. R., Bennett, M. J., & Wiseman, R. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory. International journal of intercultural relations, 27(4), 421-443.

- Ivan, D. O. R. (2012). Foreign Language Learning In The Age Of Globalization. Quaestus, 1(1), 80-84.

- Kim, J. (2006). Globalization and education in Korea: A critical comparison with Japan. Korean Journal of Comparative Education, 16(1), 75-107.

- Kim, Y. Y. (2008). Inter-cultural personhood: Globalization and a way of being. International Journal of Inter-cultural Relations, 32, 359-368. doi: 10/1016/j.ijintrel.2008.04.005

- Jackson, J. (2011). Host Language Proficiency, Inter-cultural Sensitivity, and Study Abroad. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 21, 167-188.

- Jeon, J, and Lee, Y. (2012). The Relationship between University Students' Exposure to Foreign Culture and Global Competency. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 9 (3), 157-187.

- Liddicoat, A.J., L. Papademetre, A. Scarino, M. Kohler (2003) Report on Inter-cultural language learning. Report to DEST. http://www1.curriculum.edu.au

- Miles, J, and Shevlin, M, (2001). Applying Regression and Correlation: A Guide for Students and Researchers. Sage: London.

- Olson, C., & Kroeger, K. (2001). Global competency and inter-cultural sensitivity. Journal of Studies in International Education, 5(2), 116-137.

- Panetta, L. E. (1999). Foreign language education: If 'scandalous' in the 20th century, what will it be in the 21st century? Retrieved from Grand Valley State University website: http://mybb.gvsu.edu/webapps/portal/frameset.jsp?tab_tab_gr oup_id=_13_1&url=%2Fwebapp s%2Fblackboard%2Fexecute%2Flauncher%3Ftype%3DCourse%26id%3D_53353_1%26url%3D

- Remiers, F. (2008). Educating for global competency. In J. E. Cohen, & M. B. Malin, (Eds.), International perspectives on the goals of universal basic and secondary education. (pp. 1-19). New York: Routlege.

- Savignon, S. J., & Sysoyev, P. V. (2005). Cultures and comparisons: Strategies for learners. Foreign Language Annals, 38(3), 357-365.

- Sizoo, S., Iskat, W., Plank, R., & Serrie, H. (2004). Cross-Cultural Service Encounters in the Hospitality Industry and the Effect of Inter-cultural sensitivity on Employee Performance. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 4(2), 61-77.

- Tombolato, A. M., Martino, M. A. M., & Marcos, T. A. C. (2013). The concept of inter-cultural competence: its desirability as an objective of all language classes and its realization in the English classes at Universidad Nacional del Sur. V JORNADAS DE ACTUALIZACIÓN EN LA ENSEÑANZA DEL INGLÉS, 70-.

- Vilà, R. (2006). La dimensión afectiva de la competencia comunicativa inter-cultural en la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria: Escala de Sensibilidad Inter-cultural. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 24(2), 353-372.

- Wu, H.R. (2013a). Correlation between Inter-cultural Sensitivity and English Proficiency. The 7th Aletheia University International Conference on Foreign Language Teaching and Cross-Cultural Studies.p.31-39.

- Wu, H.R. (2013). Relationships Among Inter-cultural Sensitivity, Foreign Language Proficiency, and related demographic variables in Taiwan. Taiwan: Taiwan ELT Publishing CO., LTD.

- Wu, J. F. (2015). Examining Chen and Starosta's Model of Inter-cultural Sensitivity in the Taiwanese Cultural Context. International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science (IJMECS), 7(6), 1-8.