Indefinitely on the Ice: Indigenous-explorer relations in Robert Abram Bartlett’s Accounts of the Karluk Disaster

Автор: Hanrahan Maura

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Culture of the Arctic and Northern peoples

Статья в выпуске: 20, 2015 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In 1914, the Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE) attempted to advance Canadian sove-reignty in the Arctic as part of the colonial project, itself propelled by imperialist impulses rooted in complex imperialist ideology. The CAE came to an abrupt end with the sinking of one of its ships, the Karluk, with survivors setting up camp on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. With the Alaskan Inupiaq Claude Katаktovick1, Robert Abram Bartlett, captain of the Karluk, trekked hundreds of miles over rough ice to and then through Chukchi territory in Siberia. From there, Bartlett was able to mount a rescue of the remaining Karluk survivors. Bartlett’s accounts of his weeks with Kataktovick and the Chukchi serve as a case study of explorer-Indigenous relations in the era of exploration. The Indigenous people of the Arctic were subject to explorers in a hierarchical relationship built around supporting exploration. Despite their often central and sometimes life-saving roles, as actors, Indigenous people are generally invisible in polar narratives. Yet the story of the Karluk demonstrates that, even within the constraints of this context, Indigenous people could emerge as central agents and explorers could move towards more egalitarian relations with Indigenous people.

Robert Abram Bartlett, Karluk, Indigenous—explorer relations, Chukchi, Inupiat, Arctic exploration, Canadian Arctic Expedition

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318712

IDR: 148318712 | УДК: 397+913

Текст научной статьи Indefinitely on the Ice: Indigenous-explorer relations in Robert Abram Bartlett’s Accounts of the Karluk Disaster

Introduction: Looking within the Framework

This article uses Robert Abram Bartlett’s accounts — his 1916 narrative The Last Voyage of the Karluk and his 1926 memoir The Log of Bob Bartlett — to analyze relations between Arctic

explorers and Indigenous people during the waning years of polar exploration. Besides Bartlett’s accounts, this paper is based on primary research at various archives and libraries in Canada, the United States and Britain 2. Bartlett’s accounts are not and cannot be entirely representative of explorers’ experiences because of individual differences and varying circumstances. But Bartlett’s place and status as a lauded explorer advancing imperialist ambitions resembles that of other such agents including but not limited to Fridtjof Nansen, Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton, Edward Shackleton, and Roald Amundsen. Bartlett was, for weeks, immersed in Chukchi culture as he attempted to mount an urgently needed rescue of the stranded survivors of the sun-ken Karluk . An experienced explorer by this time, he spent an even longer time in the company of a young Inupiaq, Claude Kataktovick, as the two made the dangerous trek from Wrangel Island to Siberia and along the coast to East Cape. The narratives demonstrate that

Picture 1. The Karluk cutting a path through Arctic ice in August 1913. Courtesy of Flanker Press (the National Archives of Canada [PA74047] and the Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador).

Bartlett remained rooted in the hierarchical masculine nation-building culture of exploration and generally acted to reproduce this culture’s marginalization of Indigenous people, despite the centrality of Indigenous people to the imperialist mission. Through his work Bartlett maintained the hierarchal explorer-Indigenous relationship with male and female Indigenous “local assistants,” as explorers called them, subordinate and wedded to the background with white male explorers in the foreground. Yet the generosity of the Chukchi and the courage and appeal of Claude Kataktovick coupled with the dire circumstances facing the Karluk survivors allowed Indigenous people to emerge as central actors. Further, within the longstanding framework of explorer—Indigenous relations, the story of the Karluk features encounters marked by genuine humanity.

The Canadian Arctic Expedition

The Karluk was part of the Canadian Arctic Expedition 1913—1918, at the time the largest ever scientific mission to the Arctic [1]. The expedition was international with members coming from Australia, Estonia, Portugal, Norway, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Scotland, Canada and

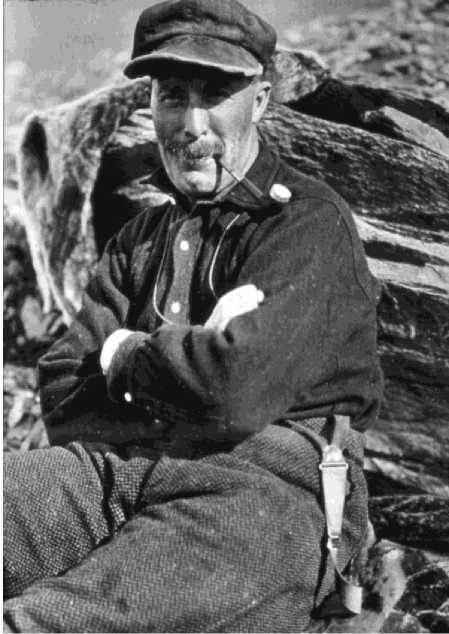

Picture 2. Captain Robert Bartlett, Peary Expedition, 1909, some five years before the Canadian Arctic Expedition. Courtesy of Flanker Press (the Peary/MacMillan Arctic Museum and the Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador).

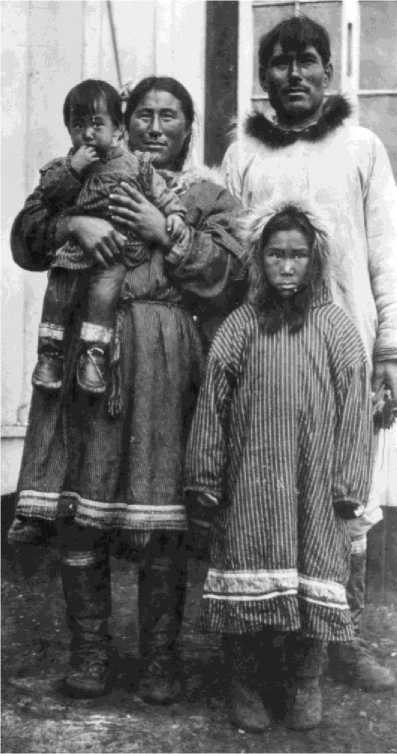

the United States [2]. It was also the Canadian government’s first such expedition to the Western Arctic [1] and had as one of its aims the advancement of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic. The Canadian Arctic Expedition included prominent scientists from several disciplines including topographer Bjarne Mamen, 22, meteo-rologist William McKinley, 24, geologist George Malloch, 33, and anthropologists Henri Beuchat, 34, and Diamond Jenness, 27 [3, p. 11], some of whom would not survive the trip. Besides scientists, there were 13 crew members on the Karluk as well as the local assistants Kuraluk, a hunter, and Kiruk, a seamstress, their children Helen and Mugpi, and Claude Kataktovick3, aged 19, also a hunter [4]. The expedition was organi-zed by the charismatic Icelandic — Canadian anthropologist Vilhjalmur Steffanson who believed there was a northern continent yet to be discovered; this was called

Theoretical Land by R.G. Harris, a mathematician with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey [3, p. 8].

The expedition was divided into two groups, each with their own mandate. The Northern Party in the Alaska would search for this land mass while the Southern Party in the Karluk , skippered by Robert Bartlett, 39, would roam the Canadian Arctic islands to conduct scientific work.

The CAE was intended to advance the Arctic sovereignty ambitions of Canada, an inheritor of Britain’s colonial project4. The colonial project itself was spurred by the deep-rooted imperialism of Western nations, imperialism being ‘more than a set of economic political and military phenomena (but also) a complex ideology which had widespread cultural, intellectual and technical expressions.” [5, p. 23]. Thus, in Linda Smith’s words, the “imperial imagination enabled European nations to imagine the possibility that new worlds, new wealth and new possessions existed that could be discovered and controlled” [5, p. 23]. Theoretical land, opined the Ottawa Journal , might be home to vegetation as well as animals, mineral wealth, and “even new families of the human race with habits, customs and beliefs that will be of exceeding interest to everyone” [6, p. 13]. “Discovery” and scientific activity were tools of this project. In this context, Indigenous peoples became objects of discovery. When the novelty of their discovery has worn off, as in the case of the Inupiat long before the CAE, Indigenous people became part of the infrastructure of exploration, much like ships, pemmican, and hunting rifles — necessary for survival but rendered passive rather than active and subject to explorers’ orders and even whims. Thus, Indigenous people were dehumanized and the Arctic was transformed from their home to an open laboratory for science and its urges towards measurement, quantification and collection, expressions of imperialist impulses and so necessary to the colonial project. Meanwhile, explorers are ennobled5, motivated, to use Amundsen’s words, by “pure unspoiled idealism” [7, p. 127]. The CAE, with its large contingent of scientists and its stated aim of discovery, epitomizes this characterization of “exploration”.

The male nature of exploration cannot be overlooked; in the western imagination, powered by imperialistic impulses, the Arctic became a masculinized place, its female residents made invisible, although in their roles as seamstresses and fishers, they, too were crucial for the explorers’ survival. As Victoria Rosner explains, “the grand heroic tradition of polar exploration defines the polar regions as all-male spaces of bonding, conquest, and noble suf-fering” [8, p. 491]. This can happen only if the unpredictability and dangers of the Arctic are emphasized, as they are in Bartlett’s accounts, and if the poles are seen as empty of women. Indeed, women rarely factor into explorers’ narratives — again, despite the contributions of Indigenous women to exploration

— and Ernest Shackleton turned away female applicants for his Antarctic voyages [8, p. 490]. The concept of the Arctic as free of women constitutes an “an aspirational fantasy rather than a practical reality” [8, p. 491] but it creates an ideal laboratory for male scientists and an undiscovered terrain for ambitious male explorers. These men, including Bartlett, were visitors and interlopers and had no legitimate claim to the Arctic, although their claims and the implications of these claims for sovereignty were legitimized by the complex ideology that is imperialism.

Newfoundland. Bartlett’s Background

Robert Abram Bartlett was born in Brigus, Conception Bay, Newfoundland, part of British Empire, in August, 1875 to a prominent family on both his maternal and paternal sides. The explorers felt ideologically comfortable in their own countries and cultures but existentially longed for the Arctic, remaining “proud of their native place, nation and culture” [9, p. 96]. This was true of Bartlett who was very much the product of his environment, itself ideally suited to exploration. His great-uncle, Captain John Bartlett, accompanied American Dr. Isaac Israel Hayes to Devil’s Thumb, Melville Bay, Greenland [10, p. 30]. John was “one of the most successful seal killers,” averaging over 69,000 seal pelts annually from 1839 to 1862 [10, p. 189]. Captain John once lost 24 men out of a crew of 40 who were fishing in small boats from his larger ship [11, p. 30], the Deerhound , but the stoicism that out of necessity characterized Newfoundland seagoing culture meant that the survivors went back to work the next day. An an obituary of Bob’s Uncle Sam read, “(Captain Samuel Bartlett was from) a famous family of Newfoundland sailing masters, which has long been identified with Arctic exploration… and has made a name for the sterling qualities of its members” [2, p. 436]. Samuel Bartlett was master of the Diana in 1899, the Windward in 1990— 1901, the Erik in 1905 and 1908, and the Jeanie the following year, all of which went to the Arctic [2, p. 436]. Foreshadowing his nephew’s Karluk voyage, Sam skippered the Neptune with the Canadian Government Expedition to Hudson Bay in 1903—1904 [13, p. 383]. This voyage advanced Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic, establishing the first Canadian Government systems of customs and justice in the islands of the Eastern Arctic. The Neptune party also claimed Ellesmere Island for King Edward VII, who was the head of state of the Dominion of Canada and of Newfoundland, her neighbour. Bob Bartlett replaced Sam when his uncle declined to accompany Peary to the Arctic in 1904 and subsequently became the first captain to take a ship north of 88 degrees [14, p. 130].

Captain John’s namesake and nephew, John Bartlett, Bob’s uncle, acted as master on Robert Peary’s ship before passing the baton to other Bartletts. John, wrote Bob, was “the first

Bartlett to get his nose away in beyond the Arctic Circle. Tales of his voyages among the ice laid the foundation for my own love of polar work on which I put so many years of my life” [11, p. 48]. John schooled Bartlett in navigation through shifting ice on the Windward with Peary and taught him how to judge distance at sea. In 1866, John Bartlett became the first Newfound-lander to earn his master’s certificate from London [15]. Bob’s uncle, Henry (Harry) Bartlett, the only Bartlett to die at sea, went north several times with Peary. Harry Bartlett had his own ambitions; as Peary’s wife, Josephine wrote, “(Harry) was determined to break the record in the crossing of this water — thirty six hours — on this his first voyage to the Arctic regions” [16, p. 214]. And he did, reaching Melville Bay in less than 25 hours [16, p. 214]. When Peary falsely claimed the North Pole, it was Bob Bartlett who took him north in the Roosevelt .

Brigus itself was an important town and the home of many notable affluent sealing and fishing captains besides the Bartletts and other relatives of Bob’s. By the mid-1700s, no less than 66 ships left Brigus annually in search of seals, several of them skippered by Bob’s ancestors [17]. Coming from such a renowned place was one factor that contributed to Bartlett’s confidence, an attribute that would serve him well in his Arctic career, especially during the Karluk saga. Brigus, then, and the Bartlett family in particular were sites that reproduced the ideology of exploration and supplied men and expertise for ventures of Arctic exploration, discovery and the commercialization of Arctic land and waters.

The Arctic Ocean. The Sinking of the Karluk

An early snowstorm on August 1, 1913 [18, p. 4] hinted at the disaster that was to come; the Karluk was in Alaskan waters, south of Point Barrow [18, p. 4]. Immediately Bartlett and his crew sighted sea ice near the cape, which turned into a solid ice pack to the eastward. Bartlett favoured a return to the south but Steffanson insisted on pushing on [18, p. 4]. Bartlett had also seen a polar bear, which he regarded as “a beacon toward future disaster”: “I am more than ever a believer in signs,” he wrote [19, p. 228], a sentiment that Katiktovik and the Indigenous Siberians the two later encountered would likely have understood. By August 12, the Karluk was stuck in the ice; the next day she was aground [18, p. 4]. This would become, wrote Bartlett, the “most tragic and ill-fated cruise of my whole career” [11, p. 227]. Pushed by the Japanese Current, the ship drifted until she was north of Alaska. She had once been within sight of land but she ended up north of Wrangel Island. On January 10, the ice punctured a hole in the Karluk ’s hull and Bartlett gave the order to abandon ship. She sank the next day. As the ship slipped below Arctic water, Bob Bartlett sat in the captain’s cabin, demonstrating his dramatic flair by playing Chopin’s “Funeral March” on the Victrola.

Picture 3. The region in which the Karluk sailed and sank. Note Wrangel Island, Russia, where the survivors camped, and Point Hope, Alaska, the home community of Claude Kataktovick.

Fortunately, the crew had long set up what came to be known as Shipwreck Camp on the ice and Bartlett directed that they would stay there until February when the Arctic darkness would decrease, allowing for travel over ice to Wrangel Island in daylight. Four of those on the Karluk — including physician Alistair Mackay, and the scientists Henri Beuchat and James Mur-ray — disagreed with Bartlett’s plan and set out for land in January, never to be seen again. In another episode that emphasized the precariousness of their situation, four crew members were lost when they got trapped on Herald Island while setting out caches for the planned trip. Stefansson was long gone, having taken a hunting party away from the ship for what he said would be a ten day hunting trip; after the ship drifted his group could not find it again [20; 6; 21].

Wrangel Island, Russia

Russia’s Wrangel Island was named for Ferdinand von Wrangel who led a Russian expedition there in the 1820s. The island is marked by mountain ridges stretching over 80 kilometers from one end of the island to the other; in the south there are coastal lowlands and in the north there is tundra [22, p. 357]. Some of the peaks reach 2500 feet and there is very little vegetation on the island, which is frequented by polar bears in the winter and birds in the spring and summer [18, p. 18]. Although it was uninhabited in 1914, fortunately, for the Karluk survivors, there was plenty of driftwood on the island [18, p. 18]. On March 12, after walking for 100 miles, the remaining 17 Karluk survivors reached Wrangel Island. Bartlett had intended to walk them all to Siberia but realized this was impossible, given the conditions, the size of the party, and the inexperience of most of its members. Those left behind would suffer semi-starvation, disease and further tragedy.

Alaska, United States

Indigenous actors in exploration are rendered almost invisible; they are transformed into infrastructure that supports the goals and work of the explorers. Although there are exceptions, such as Jennifer Niven’s Ada Blackjack (23), most polar literature pays scarce attention to the role of “local assistants” like Kuraluk, the hunter, and Kiruk, his seamstress wife, who were hired for the Canadian Arctic Expedition. Generally, polar explorers and scientists took Indigenous peoples for granted, although, again, it was very often the skills of Indigenous people that enabled the explorers’ survival. This is even true of Claude Kataktovick, the nineteen year old who accompanied Bartlett across the ice to Siberia. Fortunately Bartlett’s account of the Canadian Arctic Expedition and the Karluk has some focus on Kataktovick, with the story of his participation in the rescue attempt woven through the narratives, especially his 1916 book [20]; Bartlett also provides significant information on his encounters with the Chukchi. This gives us a case study of explorer-Indigenous relations in 1914; as the Chukchi and Kataktovick become central figures in the narratives, Indigenous people move closer to centre stage than in most other polar accounts. Claude Kataktovick in particular is presented to us as an individual, rounded out to a degree rarely seen in texts written by explorers. An even fuller understanding of Kataktovick and the Chukchi and the contexts in which they lived is possible through reference to the historical and contemporary academic literature on Siberian and Alaskan Indigenous peoples as well as Bartlett’s records.

Kataktovick was Inupiat (sometimes spelled Iῆupiat); Inupiat is plural with Inupiaq bring singular [23]. The Inupiat lived and live in Coastal Alaska and are part of the Inuit who live across the Circumpolar region 6. The Inupiat constructed driftwood and sod houses which were partly subterranean [24]; thus, Kataktovick would have spent much of his life in such structures.

Picture 4. Kuraluk and Kiruk with their two childred Helen, about 11, and the toddler Mugpi. The Inupiat couple was hired to hunt and to sew winter clothes for the Karluk expedition crew. Courtesy of Flanker Press (the National Archives of Canada [C70806] and the Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador).

Kataktovick was a native of Point Hope, Alaska, a community in North Slope Borough, Alaska, United States. These houses, home to one or two families totaling eight to 12 people, were built around another larger building, a qargi , which served as the council house [25, p. 26]. The Inupiat built their economy and society around the bowhead whale with the yearlings they often hunted weighing about 10,000 kilograms [25, p. 32]. Whalers were organized into crews that hunted from umiaks , relatively large boats, lead by umialiks , who owned the boats and the equipment, directed the rituals that governed hunting, and welded considerable social and econo-mic power in the com-munity through the distribution of resources, including whale meat and trade goods [25, p. 32]. There was, then, a well-developed social hierarchy in Inupiat so-ciety, which was “relatively stable” for almost a millen-nium [25, p. 31]. Being socialized into a rigidly hierar-chical society smoothed the transition of Inupiat into rigidly hierarchal expeditions like the CAE; Kataktovick, for instance, would have been accustomed to taking orders from social superiors like umialiks or sea captains.

While Claude Kataktovick’s ancestors witnessed little change in their lives, this was not true for Kataktovick himself who was born in a time of great transition. The three deepest changes were inter-related and had profound effects on the Indigenous people of Alaska: the decline of the bowhead whale economy; the arrival of European diseases that soared to epidemic proportions; and the rise of Christianity. Claude Kataktovick would have been born about 1895, when the bowhead whale-based economy had virtually disappeared due to American whaling activity. Its decline began in the 1850s and escalated in the 1880s [24, p. 90]. At the same time the whaling economy was disappearing, the caribou population was “all but exterminated by the Inupiat themselves, and epidemic diseases were introduced for the first time” [24, p. 90]. Burch explains the impacts as follows: “The result was the decimation of the human population. Population loss, in turn, destroyed the political basis of the traditional social system because the several societies that comprised it no longer had enough members for collective self-defense” [24, p. 90]. This, of course, set the scene for Inupiat receptivity to Christianity, a religion the Inupiat would transform according to their own belief system. Burch writes, “In 1890 there probably was not a single Christian Inupiaq Eskimo. Twenty years later, there was scarcely an Inupiat who was not a Christian” [24, p. 81]. This means that Christianity was taking root during Claude Kataktovick’s lifetime, presuming that his family, like most, would have converted. While Inupiat society was in a state of flux during this time, Christianity was very new and Kataktovick would have been raised with Inupiat values and stories as well as those related to the emerging “Eskimoized Christianity.” One example of the persistence of Inupiat culture is his fear of the Indigenous peoples of Siberia, which he would have learned from his parents and possibly grandparents who were aware of the history of warfare between Arctic peoples. Given the multiple changes that were occurring after 1000 years of relatively stability, Kataktovick’s childhood would have been stressful, even traumatic, unlike Bartlett’s, which Bartlett presents as stable and contented among the Brigus elite in his memoirs [11].

The Arctic Ocean

From Bartlett, we know that Kataktovick was a widower although he was still a teena-ger, and left his daughter with his mother to work for the Canadian Arctic Expedition; thus, he had experienced personal tragedy [26, p. 19]. Interestingly, Kataktovick could read and write and Bartlett, who often loaned him books and magazines, taught him to reach nautical charts as well [26, p. 60, p. 179]. Bartlett also gave him blank books to write in, and mused, with reference to Peary’s belief that Inuit should not become “dependent on the white man’s methods of life”, “What would Peary say?” [26, p. 60, p. 179]. Here Bartlett’s actions do not, for once, follow Peary’s. Yet his comments reflects explorers’ views of Indigenous people as fixed in time, unchanging and ahistorical; these views are rooted in and contribute to the ideology of imperialism and allowed explorers to fix Indigenous people as subject to them.

Bartlett’s Inupiat was rudimentary as was Kataktovick’s English and they seemed to have spoken a mixture of both languages to each other in a very basic way. By the time they’ve lodged at Camp Shipwreck after the sinking of the Karluk , Bartlett’s references to Kataktovick are casual, similar to the mentions of his non-Indigenous crew members and the scientists. There are, in The Last Voyage of the Karluk, many instances that demonstrate the young Inupaiq’s resourcefulness and budding leadership skills. Kataktovick spent weeks laying trails and making roads with Bartlett, sometimes just the two of them together, experiences that fueled the captain’s confidence in Kataktovick.

Picture 5. Bartlett’s chart of the Siberian Coast and the Bering Strait (Courtesy of Flanker Press).

After this work together, Bartlett decided how rescue would be achieved: “I would take Kataktovick with me. He was sufficiently experienced in ice travel and inured to the hardships of life in the Arctic to know how to take care of himself in the constantly recurring emergencies that menace the traveler on the eve-shifting surface of the sea ice” [26, p. 152]. He had originally planned to take Mamen but the Norwegian topographer had dislocated his knee; in addition, Bartlett was increasingly impressed with Kataktovick’s skills and the two had developed something of a rapport.

Chapter 19 of The Last Voyage is titled “Kataktovick and I Start for Siberia”, an intimation of the respect Bartlett had for Kataktovick and the increasingly egalitarian — given the context — relationship between them [26, p. 158]. This relationship was not one of equals, however; Bartlett was almost twice the young Inupiaq’s age and old enough to be Kataktovick’s father, he was the captain, he was a famous explorer who had navigated for Peary, and he was white. In other words, the hierarchy of the explorer-Indigenous relationship was a constant layer over all their interactions. Thus, Bartlett frequently told Kataktovick what to do, including telling him to fetch his mug from the sled to bring into a Chukchi dwelling after they had finally reach Siberia; this may sound objectionable to the modern era but would have been typical behavior shaped by the context of the expedition and explorer-Indigenous relations in this era.

Bartlett “knew as much about Siberia as he knew about Mars” but had faith that “the natives” there would help [20, p. 154]. As they traveled, the ice moved incessantly, there were blinding snowdrifts, and the light was bad. Much of the snow was deep and soft, making it difficult for the dogs and sledges as well as the two men on their snowshoes. Sledges broke and the repairs caused delays. The dogs kept chewing the harnesses and running away, with Bartlett and Kataktovick losing precious time and energy trying to catch them. They had no time to cook so ate the bear Kataktovick caught raw. The dangers of the trip necessitated constant decision-making; the dogs’ diets had to be carefully monitored, for instance, lest they overeat and become lethargic. One night the wind tore the canvas top off their igloo, exposing them to the frigid air. Bartlett had a nagging pain in his left eye, which sometimes became acute. “It was a slow job,” he wrote laconically [20, p. 190]. Kataktovick, still a teenager, got depressed a times, telling Bartlett “We see no land. We no get to land; my mother, my father tell me long time ago Eskimo get out on ice and drive away from Point Barrow never come back” [20, p. 195]. After a cruel three-week struggle over jagged ice, Bartlett was relieved when Kataktovick called, “Me see him, me see him, noone (land)!” [20, p. 179]. By the time the two reached East Cape later, 37 days had passed since they had left their companions and they had travelled an astonishing 700 miles, most of it on foot [3, pp. 232—233]. He later explained their journey to a Siberian, “Kataktovick was with me and built our igloos and killed seal and bear. An Eskimo and a white man could live indefinitely on the ice” [20, p. 204].

Encounter: Siberia, Russia

Kataktovick feared the Indigenous peoples of Siberia Bartlett and had to be persuaded by Bartlett to continue on to meet them; wrote Bartlett, Kataktovick “was sure they were going to kill him. He told me it was a tradition of his own people that the (Siberians) were a blood-thirsty outfit” [11, p. 244]. Bartlett knew he needed the Inupiaq’s cooperation and presence; his strategy was to ignore Kataktovick’s misgivings, not lending them any credence. He also tried to appeal to Kataktovick’s smoking habit and the young man agreed to carry on only when Bartlett told him he would be able to secure tobacco from the Indigenous Siberians [11]. Kataktovick’s worries were based on conventional Inupiaq wisdom which held that Indigenous Siberians were dangerous and violent; this resulted from the history of warfare in the Bering Strait region with many cases, motivated by economics, recorded in the 18th and early 19th centuries [27, p. 52]7.

Bartlett began the encounter Kataktovick so dreaded by extending his hand to the Chukchi but neither party understood the other’s language. As Bartlett put it, “they were as ignorant of my language as I was of theirs” [20, p. 191]. As Bartlett described their initial meeting “… I put out my hand and walked towards them, saying in English, ‘How do you do?’ They immediately rushed towards us and grasped us each warmly by the hand, jabbering away in great excitement” [20, p. 191]. One “native” used the mariner’s term “old man,” puzzling Bartlett at first: “His question puzzled me at first; presently it dawned on me that he was speaking in nautical parlance and wanted to know if I was a captain. ‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘You come below in my cabin, old man,’ he said, meaning that I was to go into his aranga” [20, p. 203]. It turned out that the Indigenous man knew other rudimentary terms in English; in fact, he understood “a good deal of what (Bartlett) told him” [20, p. 204]. In addition, he knew some of Kataktovick’s mother tongue. This limited language knowledge reflects the use of trade jargons in use in the Bering Straits resulting from interactions with American whalers mainly from New England beginning about 1846 [28, p. 53]. The Chukchi borrowed some English words — loanwords — mainly related to material culture, especially food [28, p. 58]. But Bartlett did not record these and relied more on paper to communicate: “By drawing pictures of trees and reindeer on the chart I found that I could make them understand what I wanted to know; then by marking on the chart they showed me that they made journeys of fifteen sleeps' duration before they reached the reindeer country” [20, p. 195]. Bartlett kept a diary and noted that he “studied” the people: “I did not, of course, acquire all my information about the natives from the first ones I met, though to be sure they were a typical group and exemplified, the more I studied them, all the customs of the country, especially that of continual feasting of the stranger within their gates” [20, p. 196]. The Chukchi were curious to know where their visitors had come from and indicated this with “signs” — hand signals. Bartlett’s response was to take out his charts and show them Wrangel Island, explaining, as best he could, his concern for the Karluk survivors who remained there.

The Chukchi lived in arrangas , fashioned from driftwood and skins which they made available to their visitors. Bartlett provided a comprehensive picture of these dwellings: “The Siberian Eskimo or Chukches, as these natives are called, know nothing of snow igloos or how to build them. Their house, as I was presently to learn, is called an arranga . There is a frame-work of heavy driftwood, with a dome-shaped roof made of young saplings. Over all are stret-ched walrus skins, secured by ropes that pass over the roof and are fastened to heavy stones along the ground on opposite sides. The inner inclosure, which is the living apartment, is about ten feet by seven; it is separated by a curtain from the outer inclosure where sledges and equipment are kept” [20, p. 192]. According to Bartlett, one arranga they stayed in held three lamps, fueled by seal or walrus oil, and was not ventilated with the result that it was hot inside, about 100 degrees, while it was — 50 outside: “Cold as it was outside, the air inside was very warm, too warm for comfort…” [20, p. 204]. It was crowded and tobacco smoking clouded the air, which Bartlett, with his abstentious background, found hard to cope with. Add to this the constant tubercular coughing of the Chukchi. Of another arranga , he wrote, “The air was hot and ill smelling, and filled with smoke from the Russian pipes which the Chukches used, pipes with little bowls and long stems, good for only a few puffs. When they were not drinking tea they were smoking Russian tobacco. All the time, with hardly a moment's cessation, they were coughing violently; tuberculosis had them in its grip.

When they lay down to sleep they left the lamps burning. There was no ventilation; the coughing continued and the air was if anything worse and worse as the night wore on. Sometime between two and three in the morning I woke up; I had been awake at intervals ever since turning in but now I was fully aroused. The air was indescribably bad. The lamps had gone out and when I struck a match it would not light. The Chukches were all apparently broad awake, coughing incessantly” [20, p. 198]. Despite his life onboard ship, Bartlett was an introvert and disliked crowds in small spaces; here he lacked the captain’s cabin which had always provided him with a solitary refuge. Kataktovick, too, may have been introverted, although he lacked a retreat onboard ship, like Bartlett. The Chukchi offered the two Karluk survivors rancid walrus meat, pemmican and deer meat and allowed Bartlett to make “strong Russian tea,” a favourite of theirs.

Besides sharing food with Bartlett and Kataktovick, the Chukchi mended their clothes and provided them with shelter. As Bartlett described it, “About eleven o'clock that night we all lay down together on the bed-platform, men, women and children; the youngsters had all remained outside the curtain until that time” [20, p. 196]. They let Bartlett borrow one of their dogs. They traded in a just manner, offering the visitors a much-needed dog for a gun, and one man went out of his way to return a dog he’d traded with Bartlett but that had run back home. Bartlett realized their level of sophistication by noting that his own behavior did not meet their standards yet they chose to ignore this. Of the dozen or so Chukchi Bartlett and Kataktovick first approached, the captain said effusively, “Never have I been entertained in a finer spirit of true hospitality and never have I been more thankful for the cordiality of my welcome. It was, as I was afterwards to learn, merely typical of the true humanity of these simple, kindly people” [20, p. 192] 8.

He was particularly taken with one Chukchi family at Cape Wankeram, noting with pleasure that the man, who he does not name, shared his love of music. This man “treated us to an extended concert, numbering 42 selections, starting off with “My Hero” from “The Chocolate Soldier”… Like the true music-lover, he kept on playing until he had finished all of his forty-two records” [20, p. 220]. That night Bartlett finally slept peacefully, which he had not done since leaving Camp Shipwreck. The Chukchi music-lover had a wife and two “fine-looking daughters” (as well as a son) [20, p. 218], and a collection of copies of the London Illustrated News, National Geographic, and The Literary Digest. Bartlett gave the family snow-knives, steel drills, a skein of fish line, a gill net, and ribbons of yard for the daughters. Bartlett was touched by the man’s action of silently harnessing up his own dogs for the visitors, writing, “Our treat-ment at the kind hands of this Chukch (sic) family will always remain in my memory” [20, p. 221].

Even Kataktovick became relaxed around the Chukchi; he was able to procure flour from one and sometimes brought messages to Bartlett from them. His behavior hinted that he recognized elements of their culture. Interestingly, he worried about the captain’s excitement and enthusiasm in conversation: “You must not talk that way,” he told Bartlett, fearing their hosts would take offence and perhaps exact revenge on the visitors [20, p. 216]. This incident reflects a certain confidence on the young Inupiaq’s part and a move away from the traditional Indigenous-explorer relationship.

There were, Bartlett came to realize, two distinct Indigenous peoples in this part of Siberia: the coast people, who were hunters and used skin boats, and the deer people. The coastal people called themselves anqa’lit while the deer people called themselves av ulat [29, p. 178]. As Bartlett wrote, “… (there were) two kinds of natives, the coast Eskimo and the deer men, the latter a hardier type of man than the former. The coast natives get their living by hunting, their chief game being walrus, seal and bear. Some of them have large skin-boats for travelling from settlement to settlement; covering in this way considerable stretches of coast. They do not go out upon the drift ice” [20, p. 196]. Like Dall in 1881, Bartlett had begun to discern the dualism that became the focus of later academic research [30; 31]. Dall wrote of the “Reindeer Chukchi (Tsau’-yū-at)”: “They are… not the wandering or reindeer Chukchi, but that part of the nation which gain their living by sealing and fishing” [32, p. 860]. As Schweitzer and Golovko explain it, echoing and expanding on Bartlett’s observation as recorded in his 1916 account, “Reindeer herders of interior Chukotka exchanged their products for sea-mammal products with coastal communities on the Asiatic and American sides of the Bering Strait [27, p. 51]. Trade was indeed important to the Indigenous peoples of Siberia; “it was not a luxury but a necessity” [27, p. 51] and could even save lives by relieving hunger. In common with most cul-tures, exchange, then, was a key to the region’s Indigenous cultures and economies. Schweitzer and Golovko characterize the area’s networks as “enduring, flexible, and ever changing” with local and global influences [27, p. 54] 9. The central place of exchange in the region served Bartlett well as he and Kataktovick journeyed along the coas10t; their presence was accepted and they were able to trade items with the Chukchi and give gifts as forms of thanks, news of which would be forwarded to the next village they would be passing through.

The Rescue of the Karluk

Bartlett left Cape East on the Herman and wired Ottawa, the Canadian capital, from St. Michael, Alaska. He recovered from severe swelling in his legs, which virtually paralyzed him, while seeking a rescue ship. He sailed in the Bear , an American ship, on July 13, 1914 and was reunited with the Karluk survivors when the Bear met the King and Winge , a Canadian ship that had rescued them the day before [20, p. 277]. Thus, on Sunday, August 9, 1914, the anthropologist Stuart “Diamond” Jenness of the CAE began his diary entry “Great news” [33, p. 261]. Bartlett had reached Plover Bay (Siberia) “all in — he could hardly stand his feet were so broken up” [33, p. 261]. Jenness summarized the story of the Karluk as follows: “The Karluk drifted about 60 miles off the coast of Herald Island, about 65 miles from Wrangel Island in January. Here she was crushed by the ice … She sank with the (Canadian) flag flying, and the ice closed over her again. The men made Wrangel Island with provisions for 80 days and plenty of guns and ammunition. (Bartlett) with a Port Hope 11 Eskimo — Claude Kataktovick — crossed over to the mainland… The Herman butted through the ice at Plover Bay, picked up Captain Bartlett, and took him to Nome, whence he was telegraphing out.” [33, p. 261]. In keeping with the style of most exploration narratives, Bartlett was the central figure for Jenness who mentioned Kataktovick only in passing. Meanwhile one survivor had died of a gunshot wound on Wrangel Island while disease had struck down two others, including Mamen, who had hoped to do the role Kataktovick did. It is interesting to speculate how Bartlett’s and secondary narratives would have been shaped if Mamen, a Norwegian, had trekked to Siberia with Bartlett instead of the Inupiaq.

In 1914, there was great interest in the story of the Karluk , despite momentous events happening in Europe, and this interest was sustained. In November, 1916 the New York Times published an account by Bartlett and a chart showing the ship’s progress until it was crushed [26].

Picture 6. The Karluk survivors on board the Bear : Captain Bartlett is fourth from the left (Courtesy of Flanker Press).

Meanwhile, Bartlett, at least, expressed his appreciation for the skills and companion-ship offered by the young Inupiaq and sent his pay along to him as soon as was possible. Of their leavetaking at the East Cape, Bartlett wrote, “… we were parting here. I thanked him as I bade him good bye, for all that he had done, and told him how greatly I was indebted to him for his constant help and for his faith and trust in me” [20, p. 240]. Almost fatherly, Bartlett added, “I asked Mr. Carpendale (a trader) to tell the Chukches what a good boy Kataktovick was. I gave him the rifle we had carried on our journey and some other things we had with us, and then we shook hands warmly and parted” [20, p. 240]. By the time Bartlett wrote his book about the Karluk , he had, for the second time in his life, made international headlines; he was ensconced in popular consciousness as a man’s man, a true hero, an icon to be admired and emulated. The crucial role of the teenaged Inupiaq Claude Kataktovick and the exceedingly generous Chukchi of Siberia in the Karluk rescue, meanwhile, faded into history.

The Meaning of the Encounter

Western intellectuals lack the cultural background to understand non-westerners (such as Indigenous people) and represent their experiences [34] so it is hard to understand the motives and perspectives of the Indigenous people who engaged in or supported Arctic exploration. Perhaps not surprisingly, explorers rarely tried to understand and seemed, at times, not even to realize that other — valid — perspectives existed; Peary and Bartlett, for instance, were both critical of the “spells” of Ahngoodloo, an Inuk, who was likely experiencing stress in reaction to the inherent power relationships and possible power abuse inherent in Arctic exploration [19, p. 2].

Indigenous analyses are sorely needed but there are few written accounts by Indigenous people, especially from the era of Arctic exploration11.

Albeit from an explorer’s perspective, Bartlett gives us a window into the life of the Chukchis after whaling had declined and before they were radically changed by external forces, specifically policies in the Soviet era which would begin a few short years after the Karluk drama. Although there is evidence of trade and sickness, Chukchi values and mores seemed essentially intact in 1914, at least from an outsider’s perspective which lends the account some poignancy. Chukchi material culture seemed to be mainly Indigenous but they eagerly embraced items imported by the explorers and the whalers. It is impossible for us to know if the Chukchi felt their culture and economy were threatened or if they had the sense that their openness and ministrations likely saved the lives of their two visitors and, indirectly, the lives of the Karluk survivors.

We need to build on our attempts to understand the relationships that developed between “local assistants,” who were Indigenous, and the white men who were frequently the recipients of international accolades, as Bartlett was; particularly needed are Indigenous perspectives on these relationships. Bartlett uncritically used language that reflects the ideology of imperialism, so central to his profession and peers; he wondered, for instance, if Chukchi were “afflicted with tuberculosis, to which so many primitive races have succumbed after contact with the beneficent influences of civilization” [20, p. 186]. Yet Bartlett’s telling of the Karluk story is interesting in that it shows that the captain himself, while still very much entrenched in explorer-Indigenous power relations, had become tranformed to the point that he was able to individualize, respect and give credit to at least one Indigenous person, Claude Kataktovick. He did not record any of the names of the Chukchi in his accounts, although he mentions writing some of them down but losing the paper. He did not romanticize the Inupiat or the Chukchis, writing of an arranga, “It smelled worse than any Greenland igloo I have ever been in, which is saying a good deal” [11, p. 244]. This, in combination with his habit of seeking advice from Kataktovick and writing about this practice, suggests that Bartlett did not patronize the Chukchi or the Inupiat. Bartlett also tried to model courtesy in Siberia and praised the hospitality that probably saved his life. This is but a small debt repaid to the Indigenous people who were so vital to Arctic exploration and to whom exploration cost a great deal; still, it merits some attention. Bartlett’s views of and relationships with Indigenous people occurred as part of an imperialist push, given that the Canadian Arctic Expedition aimed to advance the assertion of Canadian sovereignty over the Arctic, which was consistent with goals throughout the era of “exploration.” The captain’s account, however, demonstrates that, even in this sort of power-riddled and unjust scenario, genuine humanity can assert itself from all sides.

Although he has been for decades, Claude Kataktovick should be overlooked no longer. Through this young man, we are provided with an example of a skilled Inupiaq who was largely responsible for the rescue of the stranded survivors. Above all, Kataktovick was a resilient Inupiaq, a young widower who was set to remarry — to begin again — after a life of considerable turmoil, including the accomplishment of a harrowing walk from north of Wrangel Island to Siberia and the East Cape.

Список литературы Indefinitely on the Ice: Indigenous-explorer relations in Robert Abram Bartlett’s Accounts of the Karluk Disaster

- Gray D., Canadian S. Arctic Expedition 1913—1918: Commemorating the 100th Anniversary. Metcalfe, Ontario: Grayhound Information Services, Available at: http://canadianarcticexpedition.com (Accessed: 12 July 2015)

- Canadian Museum of History (n.d.) The Team. 1913—1918 Expedition. Gatineau, Quebec: Canadian Museum of History. Available at: http://www.historymuseum.ca/arctic/theexpedition (Accessed: 22 May 2015).

- Niven, Jennifer. The Ice Master: The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk. Basingstoke, UK: Pan Books, 2000

- Canadian Museum of History (n.d.) The People of the CAE. 1913—1918 Expedition. Gatineau, Quebec: Canadian Museum of History. Available at: http://www. historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/hist/cae/peo60e.shtml. (Accessed: 22 May 2015).

- Smith L. T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed., 2012

- May be ‘Inside Story’ in Steffanson’s Plight: Why Did He ‘Lose’ Ship? Ottawa Evening Journal, 11 December 1913, p. 1.

- Ikonen H.M., Pahkonen S. Explorers in the Arctic: Doing Feminine Nature in a Masculine Way. Encountering the North: Cultural Geography, International Relations and Northern Landscapes. Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate, 2003, pp 127—151.

- Rosner V. Gender and Polar Studies: Mapping the Terrain. Signs 34, 2009, no. 3, pp. 489—494.

- Tan, Yi-Fu Desert and Ice: Ambivalent Aesthetics. The Wasteland: Desert and Ice. Barren Landscapes in Photography. Vienna: Atelier Augarten, 2001

- Shortis H.F. (n.d.) Notes from a Diary and Some Recollections. Papers of H.F. Shortis. 189: 189—194.

- Bartlett R. A. The Log of Bob Bartlett. St. John’s, Newfoundland, Flanker Press. 2006

- Author unknown Obituary: Captain Samuel Bartlett. Geographical Journal, no. XLVIII, 1916 p. 436.

- American Geographical Society (Nov., 1916) Obituary: Captain Samuel W. Bartlett. Geographical Review 2 (5): 383.

- Hanrahan M. Bartlett, Robert “Bob” Abram (1875—1946). In Antarctica and the Arctic Circle: A Geographic Encyclopedia of the Earth’s Polar Regions. Andrew J. Hund (ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol. 1, pp. 130—131.

- United Kingdom and Ireland (1866) Master’s Certificate of John Bartlett. Masters and Mates Certificates, 1850—1927.

- Diebitsch-Peary, Josephine My Arctic Journal: A Year Among Ice-Fields and Eskimos. New York: The Contemporary Publishing Company, 1893.

- Wells R. The Town of Brigus Available at: http://www.brigus.net/wells.htm (Accessed: 12 July 2015)

- Horwood H. Bartlett: The Great Explorer. Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1989

- Dick L. (1995) ‘Pibloktoq’ (Arctic Hysteria): A Reconstruction of European-Inuit Relations. Arctic Anthropology, 1995, 32 (2): 1—42.

- Bartlett R., Hale R. T. The Last Voyage of the Karluk: Shipwreck and Rescue in the Arctic. St. John’s, Newfoundland: Flanker Press, 2007

- Stefansson V. The Friendly Arctic: The Story of Five Years in Polar Regions. New York, Macmillan, 1922

- Kos’ko, M.K., Lopatin B.G., Ganelin V.G. (1990) Major Geological Features of the Islands of the East Siberian and Chukchi Seas and the Northern Coast of Chukotka. Marine Geology, 1990, pp. 349—367.

- Okakok L. Serving the Purpose of Educaiton. Student paper. New York, Borough of Manhattan Community College.

- Burch E. S., Jr. The Inupiat and the Christianization of Arctic Alaska. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 1994, no. 18 (1-2), pp. 81—108.

- Friesen T. M. Resource structure, scalar stress, and the development of Inuit social organization. World Archaeology, 1999, no. 31 (1), pp. 21—37.

- Bartlett R. A. Captain Bartlett’s Story of the Karluk’s Last Voyage. New York: New York Times, 19 November 1916, pp. 1-?

- Schweitzer P. P., Golovko E. Traveling between Continents: The Social Organization of Interethnic Contacts across Bering Strait. The Anthropology of East Europe Review, 1995, no. 13 (2), pp. 50—55.

- De Reuse W. English Loanwords in the Native Languages of the Chukkotka Peninsula. Anthropological Linguistics, 1994, no. 36 (1), pp. 56—68.

- Svanborg I. Chukchi. Antarctica and the Arctic Circle: A Geographic Encyclopedia of the Earth’s Polar Regions. Andrew J. Hund (ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol. 1, pp. 177—181.

- Kerttula A. M. Antler on the Sea: Creating and maintaining cultural group boundaries among the Chukchi, Yupik, and Newcomers of Sireniki. Arctic Anthropology, 1997, no. 34 (1), pp. 212—226.

- Vaté, Virginie. Maintaining Cohesion Through Rituals: Chukchi Herders and Hunters, a People of the Siberian Arctic. Pastoralists and Their Neighbours in Asia and Africa. Senri Ethnological Studies , 2005, no. 69, pp. 45—68.

- Dall W.H. On the So-Called Chukchi and Namollo People of Eastern Siberia. The American Naturalist, 1881, no. 15 (11), pp. 857—868.

- Jenness S. E. Through darkening spectacles: memoirs of Diamond Jenness. Gatineau, Quebec, Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2008

- Spivak G. Can the Subaltern Speak? Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (eds.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, pp. 271—313.