Investigating and analyzing the motifs of the tombstones of the Ounar cemetery

Автор: Parvin S., Afkhami B., Hendiani E.

Журнал: Краткие сообщения Института археологии @ksia-iaran

Рубрика: Исследования в Центральной Азии

Статья в выпуске: 259, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Tombstones have great importance in belief and artistic areas due to their close connection with human beliefs. Meshkinshahr’s city was selected as the studied area because of its location in a particular geographical area and its proximity to the Safavid religious capital (Ardabil) as well as its richness in terms of Islamic gravestones and lack of adequate studies in this area. Among the cemeteries of this city, the cemetery of Ounar was investigated due to presence of the main type of graves and various symbolic motifs. The purpose of this study was to identify typology, analyze the used symbolic designs or signs, particularly, paintings assigned to the Shiite religion, and chronologize the gravestones. This research has been conducted through field surveys and library studies based on the descriptive-analytical approach. The conducted studies have shown that the chronology of most graves is related to the Safavid period and the most common motifs are associated with religious traditions. The prayer of the Great Salat and the stylized three-leaf palm image is the symbol of Imam Hussein’s tomb which was common in the Safavid era (the 16th - mid-18th centuries).

Tombstone, cemetery of ounar, symbolism, decorative motifs, safavid era, shiite art

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143173128

IDR: 143173128

Текст научной статьи Investigating and analyzing the motifs of the tombstones of the Ounar cemetery

Although beautiful category and showing beauty of art works has been considered as an important feature of the art of Islamic Iran, decorative motifs have gone beyond the status of apparent beauty in Iranian Islamic art. The appearance of many artistic designs has been the beginning of inner and internal meaning in Iranian Islamic art. So, the main purpose of the artist was not to design such roles only because of his beautiful works of art and these motifs contained symbolic concepts in their appearance (Khazaeе, 2007. P. 24). Among the works of Iranian Islamic art, the gravestone along with symbolic motifs carved on the graves has a special status as a permanent http://doi.org/10.25681/IARAS.0130-2620.259.398-410

monument in Iranian culture and due to the widespread support of the Muslims ( Shayestehfar , 2009). Symbolic motifs carved on Iranian gravestones show the appearance of sensational phenomena and the events of the foreign world. In general, these symbols include any speech and image that, in addition to its obvious and explicit meaning, they also had hidden allegorical meanings in themselves ( Jamshidi , 2013. P. 8, 9). Gravestones, due to their particular connection with humans, represent a suitable platform for displaying ideas and thoughts from people in different regions, and the main reason for referring of artists to encoding and symbolism is the fact that the decoding has been an instrument, the oldest, and the most basic expression of concepts ( Shayestehar , 2010. P. 94).

We seem as a species to be driven by a desire to make meanings. Distinctively, we make meanings through our creation and interpretation of «signs». Indeed, according to Peirce, «we think only in signs» ( Peirce , 1931–58. 2.302). Anything can be a sign as long as someone interprets it as «signifying» something – referring to or standing for something other than itself. We interpret things as signs largely unconsciously by relating them to familiar systems of conventions. It is this meaningful use of signs which is at the heart of the concerns of semiotics ( Imamifar , 2009. P. 5).

In fact, the study of some phenomena in terms of semiotics is as paying attention to the way in which they create their meaning. In other words, it is a method by which phenomena can induce signification or interpretation). Nothing is a sign unless it is interpreted as a sign and it induces a tacit behavior in the minds of the individual or those who receive it ( Pahlavan , 2006. P. 14).

Semiotics

A symbol or sign is the «best possible description, or formula of a relatively unknown fact which cannot conceivably, therefore, be more clear or characteristically represented» ( Dallasho , 1985. P. 9). «The symbol explains everything and directs the person to a concept which is too inconceivable. It has a preconceived ambiguity and no word in any of the common languages can fully express it» ( Chevalier, Gheerbranl , 1999. P. 34).

Symbols are not specific to a particular product or form in human life, but the symbol may be the concept, color, rituals, important time, historical location, number, slogan, code, utterance, flag or slogan. Today, symbols are often referred to as meaningful images and forms, and this usage is due to the high use of images and forms in symbolism ( Foladi, Hassanpour , 2015. P. 142).

The best way to recognize symbol is to understand how traditional civilizations deal with symbol and concepts. In these societies, symbol or sign is not the only concise word, but it is also the relations between the signifier and the signified of human and God. The rituals of symbols are related to the self-knowledge of humans. Symbol is one of the tools of knowledge, the oldest and the most basic form of expression. A tool reveals concepts that cannot be expressed otherwise ( Cooper , 2000. P. 1). Understanding the symbols of a culture, on one hand, helps to better understand beliefs in that culture, and on the other hand, it shows how people are treated and expressed in different ways.

Geography of research

The Ounar village is located ata rough area on the northern side of Sabalan mountain with a longitude of 47 degrees and 52 minute and a latitude of 38 degrees and 29 minutes. This village is located 26 km from Meshkinshahr city of Ardabilprovince of Iran and 8 km from the city of Lahrud. The village is surrounded by the villages of Babian, Al-Dara, Lanjabad, and Dashkasan on the south, Fakhrabad city on the north side, Lahrud city on the west side, and the villages of Qozlou, Ali Abad, and Kovich on the east side ( Pouriman , 2001. P. 168).

In the center of the village of Ounar, there is an Islamic cemetery surrounded by rural houses. The cemetery consists of two parts, the northern part approximately 60 to 70 meters in dimension and the southern part with approximate dimensions 70 to 40 meters. These two parts are divided by a rural road. In the southern part of the cemetery, there are three monuments (standing stones) with 12 gravestones having altar-shaped motifs in upper view and epigraphic decoration in an environment with approximate size 4,7 to 3,5 meters. The Cultural Heritage Organization has fenced off this area to protect it against abusive individuals. This Islamic cemetery is still functioning burials are practiced till now. This cemetery consists of Islamic Safavid tombstones and new era graves. Within the cemetery 71 monuments were identified on which this research is based.

The name and historical background of Ounar

Ounar consists of two words, namely «Oun» and «ar» (arkh). «Oun» means ten in Turkish language and «ar» means a river or a stream. The reason for this name is due the fact that there are ten rivers or streams flowing down the slopes of the Sabalan Mountains in spring, joining together in the village of Ounar, and forming the Ounar river.

In another narrative, «Ounar» means the place of flouring, because in the old times, there were 18 water mills in this village, so wheat of the surrounding areas including Moghan and Arshaq were floured in this village ( Nobakhti Xiyavi , 2001. P. 83).

The motifs used in the tombstones of the cemetery of Ounar

The motifs or designs used in the Cemetery of Ounar are divided into six groups: 1 – inscriptions; 2 – vegetal or plant motifs; 3 – animals; 4 – humans; 5 – war equipment; 6 – geometric designs. In the meantime, geometric patterns or motifs themselves are divided into several types, which will be discussed below. One of the most important motifs used in decoration of tombstones is inscription.

Inscriptions (Quranic verses and prayers on the tombstones of Ounar)

The use of inscriptions is one of the most common decorations in the cemetery of Ounar. The theme of the inscriptions contains prayers, Qur’anic verses, and the holy name of Imam Ali (as) in the form of chalipa. Among Qur’anic verses used in the tombstones of Ounar, Al-karsi verse can be mentioned, which was used in one case. Among prayers, the prayer of the great Salavat repeated in three cases of tombstones can be mentioned, all of which are silvered in the four views of tombstones. Al-karsi and its position is as follows: Abu al-FathRazi writes Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) narrates from Imam Ali (as) that the Qur’ān is Seyyed of words, the Surahal-Baqarah is Seyyed of the Qur’an, and the verse of Al-karsi is Seyyed of the Surah al-Baqarah.

Vegetal or plant motifs

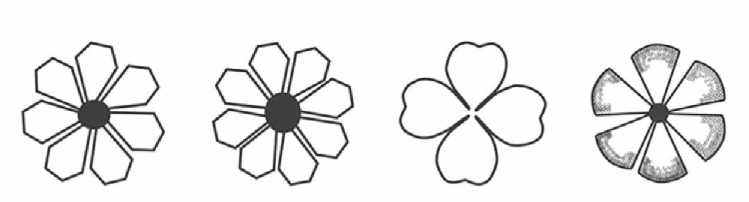

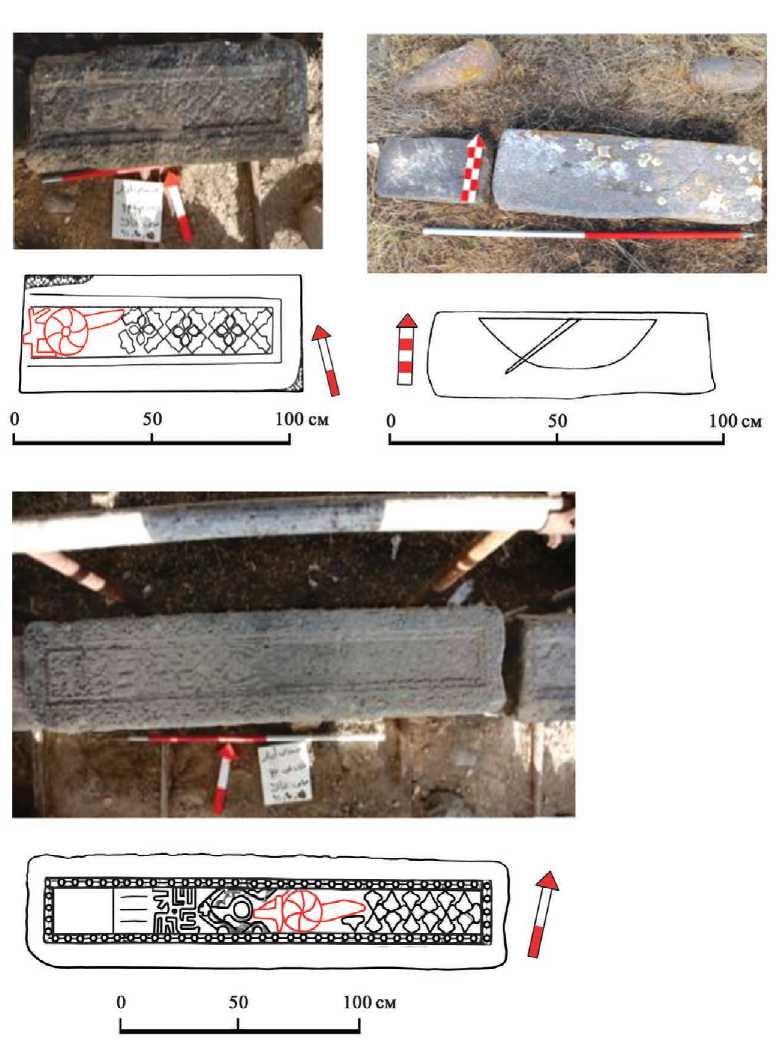

Tree plays a special role in Iranian art as a decorative plant design. This plant has long been regarded by human beings and has a sacred place in human mind, and its static and strong form is a symbol or sign of life and resistance ( Widengren , 1999. P. 70). Showing various life situations and life cycles can be found in plant or vegetal symbols including flowers. Plant or vegetal symbols are generally signs of death and revival. Flower is the sign of vegetal stage of life and is also the example of life instability. The goal is both time and eternity. It represents Life and death aswell. Flowers are a symbol of paradise, and illustrate the instability and transitory of life. The flower is the epitome of eternal life and the eternal spring of the resurrection in the sense of communicating with the funeral ceremony. Flowers or herbs repel evil and help the dead. Therefore, the use of flowers in funeral ceremony can be considered as deriving from the same tradition. The four-leaf, six-leaf, seven-leaf, and eight-leaf flowers (rosettes) are used in the cemetery of Ounar (Fig. 1). In all cases, the flowers are located on the two ending sides of the altar design and only in one case, the four-leaf flower has been designed in the bottom and initial part of the tombstone. It seems that the four-leaf flower had been a symbol of chance for the grave owner.

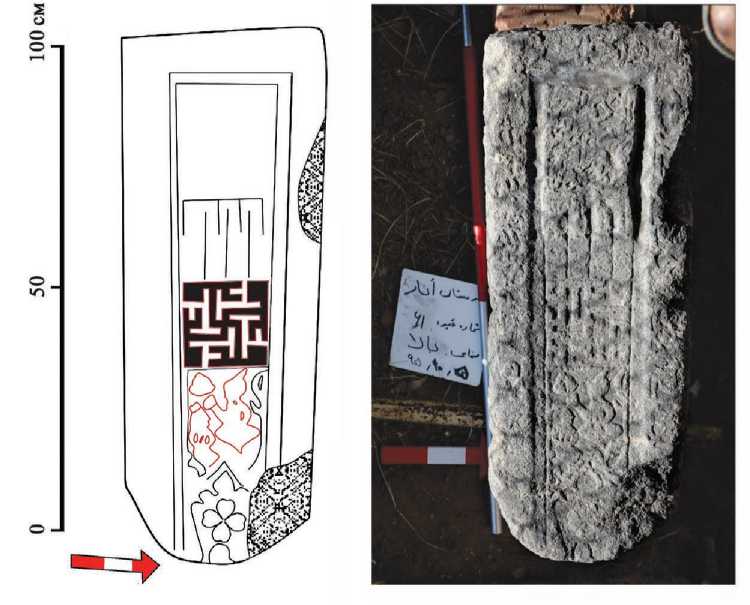

Fig. 1. Cemetery of Ounar. The design of the flowers on the tombstone (the authors)

Eight-leaf flower

Many scholars and researchers have considered eight-leaf flower as water lily (lotus). Water lily is a famous symbol of Mehr and Anahita growing on the surface of water. On one hand, lily (Niloofar) is associated with the water (Anahita), and on the other hand, with the Sun (Mehr). In ancient Iranian mythology, lily has been considered as Anahid. «Venus» was the main imagination of the essence of existence in the ancient religious narratives of Iran. In the ancient narratives of Iran, the flower of water lily (Lotus) was considered as the preservation of seed or the Zartosht’s far, which was kept in water. Hence, lily is closely associated with the ritual of Mithraism (Yahaghi, 1996. P. 429). The eight-leaf flower has been the epitome of sun from the first historical periods (Afrouz, 2014. P. 138).

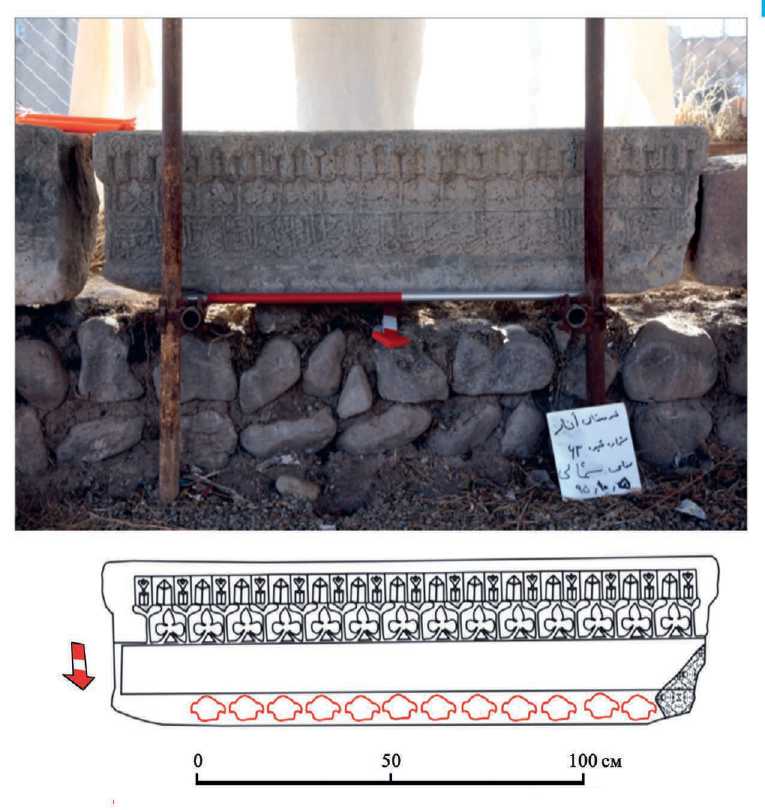

Nakhl means the palm tree in dictionary and is figure of every decorative tree. Nakhl is symbolic representation of Imam Hussein’s coffin and the martyrs of Karbala in the public culture. This design is seen as stylized, simple, and three leaves in the tombstones of Safavid period in Ounar and in shahidgah Ardabil , which is repeated in a row in the lower part of the four views of this design. (Fig. 2). Also, the design in Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardebili’s Tomb is a symbol of this incident that

Fig. 2. Cemetery of Ounar.

The row of three-leaf palms or Nakhls and the Mogharnas motifs has put the body of Imam Hussein (AS) on the palm leaves and buried it. This Shia symbol has been popular since the Safavid era and has even been celebrated as palmcarrying (Nakhl Gardani) since that time.

Animal motifs or designs

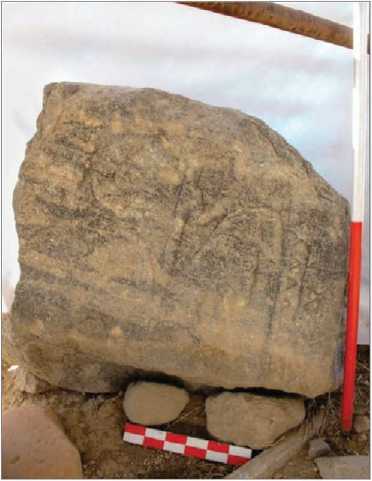

In the history of human civilization, and during their evolution, human beings have always been influenced by the mystery of the world of animals, and sometimes by their beauty and power. The accompanying animals had been considered one of the most important sources of visual artwork as an integral part of the countless manifestations of nature. Whether animals used as a source of food obtained through hunting, whenever they succeeded to force different animals accompanying them and domesticated them, they always create imagining picture in their mind and thought. The impacts of these ideas, both on the prehistoric caves and on today’s monuments on gravestones, have always been a symbol of power and majesty of those animals, and by illustrating them, they want show us something. Thus, this imaging was not purposeless and in vain. In the Cemetery of Ounar, there is only one design of horse in a single case. Unfortunately, the grave is broken down from the middle part and the other part is also destroyed. The full design of this tombstone has been designed and reconstructed from an old image, while the tomb was still intact (Fig. 3). In this tomb, two human beings were pictured on the two sides: one person pulls the horse toward himself in one side, and on the other side, the opposite person pulls the animal that seems to be a goat. Concerning this design, it can only be stated that it is a scene of exchange and the sign of a rural life, but the reason for its picturing on the grave is unknown.

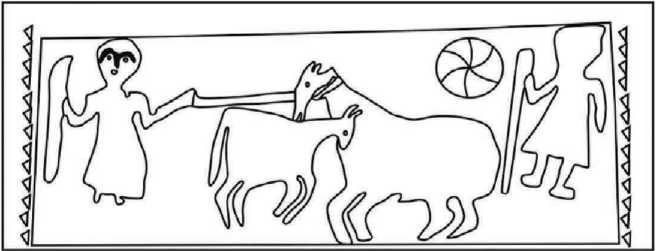

Human motifs or designs. In the cemetery of Ounar, human motifs are only designed or painted in two tombstones. One of them is the scene of exchanging horse and goat. In this tombstone, the design of human is clearly presented in a very primitive and simple way, and the design of the face is not clear or it has eroded or destroyed due to erosion and fracture. On both sides, two persons holding a stick each and in uniform clothing that has been prevalent in the past induce a manner of rural life. Another tombstone shows the design of two persons, both sitting together on their knees (Fig. 4). One of the images is represented slightly larger and higher. Since the designed shape and image of the human and its hat looks similar to the hats of the Safavid era, it seems to be related to this period. In this design, it looks as if the person presented in larger size is lecturing or teaching something the opposite person. This is deduced from the manner of sitting of both persons, when the opposite person who puts his hands on his feet as a sign of respect is looking at the opposite side.

War equipment. With respect to the growth and development of the economy, raising of the cultural level of human societies, and the transformation in the domain of religion, the of putting instruments and gifts inside the tombs has undergone a major transformations and changes. This tradition has been abolished in a way that other people were forbidden by the divine religions to place gifts into the grave. But artists of this area, with a certain cleverness and abundance of intelligence, engraved the images of gifts on tombstone instead of actually presenting the real gifts in tombs, and thus this tradition continued in a different way. Although, in the old

Fig. 3. Cemetery of Ounar. Animal images on the tombstone (the authors)

days, the goal of placing gifts was to help the dead soul to reach safely the world of the dead and use them to survive in other worlds, this engraving tradition is now only used to identify the dead’s job during his lifetime. Sword is the symbol of power, ability, and justice, and a sign of the gods, heroes, and martyrs of Jesus; and since their number is countless, their identification is difficult. The weapon that was taken from the defeated enemy, had been considered as the symbol of unconquerable power and strength in the hands of the conqueror.

Among the instruments of war used in graves of the cemetery of Ounar can be pointed to a dagger or sword and bow, which have been used in limited cases. The design of arch has been used in one case only painted at an elementary level, but the design of sword and shield has been used in two cases on the tombstones (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Cemetery of Ounar. Human images on the tombstone (the authors)

Geometric designs or patterns

Mihrab (altar). Mihrab is possibly derived from the verb ḥariba («to fight», from the root Ḥ-R-B), so itwould mean «battlefield» or «place of fight with Satanand passion», and it follows qibla direction ( Tafazoli , 1997). Thus, the wall in which a mihrab appears is the « qibla wall». In the term of wayfarers or mystics, every desire and purpose that attracts or captures the hearts of people is called mihrab ( Sajjadi , 1996. P. 705). In fact, mihrab is a semicircular niche in the wall of a mosque which is separated from other parts of the building in different ways such as frame-making and distinguishing it by color and materials, and it is an indication for determining the direction of the qiblah . In the 4th and 5th centuries AH, when artists’ attention was turned back to carving after several centuries, building of stone altars and also altar-shaped tombstones became prevalent ( Sajjadi , 1993. P. 140). Mihrab can be considered as the symbolic gate of paradise, in which all thoughts come to the Creator and all eyes stream in one direction. It is undeniable that mihrab had been designed on tombstones. It is mihrab by which a human communicates with the other world and

Fig. 5. Cemetery of Ounar.

The design of bow, sword and dagger on the tombstones (the authors)

approaches God. As the living are connected to the Malakot world by praying in front of mihrab in mosques, the dead also take their souls to the Malakot world; this symbol shows that every place has a door and mihrab exists in paradise. In the cemetery of Ounar, there are various mihrabs or alters on tombstones indicating the religious beliefs of the buried people.

Triangle. The equilateral triangle symbolizes divinity, harmony, and proportionality; this symbol refers to the number three and is completely incomprehensible without communicating with other geometric shapes. In fact, all forms can be divided into triangles by drawing lines from the center to the angles. Triangle forms the base of the pyramid. As any birth is performed by division, mankind is also comparable to an equilateral triangle that has been divided into two right angled triangles. Plato, in the Timaeus dialogue, considers it as the sign of the earth. The triangle has different concepts in different positions and designs; the upward triangle is the symbol of fire and the male gender, while the downward triangle is the symbol of water and female gender. The triangle associated with the sun and wheat is a symbol of fertility. Of course, the design of the BC triangle was a sacred one, and this kind of instrument was used to summon the soul and spirit ( Motavali , 2013. P. 124).

Triangle is sharp. It is a sign of burning, vitality, and liveliness. It is the sign of water and an inspiration to the history of countless religions around the world. Hence it is also the sign of rising of evolution. Each of the different forms of the triangle is a symbol of a concept, but they are not so different in their totality (Ibid. P. 125). Among the designs of the tombstones of Ounar, the design of triangle has been used twice for decorating and framing.

Tasht (wash tub). «Tasht» (wash tub) is a topic for craved designs or motifs on ancient graves, often created as small or large ponds in various geometric shapes. Tasht, as its name shows, is the place of accumulation of water (the element of life and light), ornamental and meaningful elements of graves that are carved into the heart of tombstones.

Tashts are not only related to Iran and the Islamic world, but those resulted from a common global thinking and attitude in various civilizations, especially in the East, so that these types of motifs exist besides the plenty and abundance of steel throne in the Armenian tomb of Isfahan, among the Jews, and even the Far East. Tashts have elements of work and semantic features that have gradually been identified with beautiful concepts. Although they sometimes seem simple in appearance and form, these mysterious forms are associated with aspects of sacred and eternal. Tashts, which had a special place in some of the ancient tombs, were cut into tombstones, and were presented in beautiful and diverse geometric forms with elements such as fish and angels, but they also had a close connection with water stones, ponds, and Sagha-Khaneh. Basically, tasht should be carved and designed in such a way as to contain a large volume of water, and so the shapes that were accidentally carved or designed with other applications on the tombstones should not be considered the same with tasht of water. The abundance of water is a sign of abundance of blessings and fertility ( Rismanchian, Heidari , 2005. P. 4).

In the Holy Quran, the importance of water is so great that the word «ma’a» is repeated 63 times, and it is referred to as symbol of goodness, blessing and purity. Meanwhile, the words such as «Kowsar» are another evidences of holiness of the spring, the stream, and the water in general. In Iranian mysticism and wisdom, water has a profound conceptual layer. In the cemetery of Ounar, tasht of water has been carved in a very simple and primitive manner in the middle of the tomb or in the right side.

Muqarnas. Muqarnas can be regarded as the manifestation of multiplicity toward unity and unity toward multiplicity. This ornamented element, while composed of plural sets of motifs and spacing, is understood as a unique element. Using Muqarnas on the tombstones, similar to mihrab can also be a symbol of the window and gateway to the paradise. Muqarnas is the place of light, and the purpose of carving it on the tombstone is probably shining light as a manifestation of God. On the tombstones of Ounar, the Muqarnas working consists of two altar-shaped forms that are carved on the upper edges of the tombstones on each of its four sides. These cornices are performed on a row of three-leaf flowers and plant stems (Fig. 2). This type of motifs has been carved in the same style on the body of the tombstones in the cemetery of shahidgah Ardabil. Regarding the type of designs and uniformity of motifs used on the tombstones of Ounar and shahidgah, it seems that these two cemeteries are related to the same period of time. Since the cemetery of shahidgah belongs to the cemetery of the Safavid era, thus, according to the available evidence, the tombstones decorated with these types of motifs can be attributed to the Safavid era.

Conclusions

After death, humans usually take their beliefs and attitudes of their lifetime into life after death through burial in graves, including customs and prehistoric rituals and use them in the other world, or like today, engrave it on tombstones according to the religious teachings that prohibit the burial of any object with the dead. These motifs can be based on the individual’s job or Quranic verses and various prayers used during his lifetime for forgiveness in the afterlife.

There are a variety of decorative motifs including sword, shield, and bow on the tombstones of Ounar, which represents the occupation of the individual in this world. Warriors have always been fighting and deserving respect. They like to leave behind their deaths some works reflecting their courage and valor in this world. Therefore, carvers try to depict person’s life and his occupation in this world by carving designs on tombs. These designs or motifs, in addition to showing the deceased’s occupation, can reflect other aspects of the individual’s life including his beliefs and attitudes. Using the design of three-leaf palm trees in a simple and primitive form, which is a symbol of the coffin of Imam Hossein (AS), reflects the Shiite beliefs of the buried people.

Список литературы Investigating and analyzing the motifs of the tombstones of the Ounar cemetery

- Afrouz M., 2014. Sign and Symbolism in Iranian Carpet. Tehran: Mardashti Cul-tural Center.

- Chevalier J., Gheerbranl A., 1999. Dictionary of Symbols / Transl. by Sudabeh Fathhali. First Printing. Tehran: Jeyhonon Publications.

- Cooper J. C., 2000. Illustrated Culture of Traditional Symbols / Transl. by Malihe Karbassian. Tehran: Nar Farhad.

- Dallasho M. L., 1985. Legendary mystic Language / Transl. by Jalal Sattari. Te-hran: Toos Publishing.

- Foladi M., Hassanpour M., 2015. The role of symbols and symbolism in human life: Sociological analysis // Journal of Cultural and Social Knowledge. Vol. 6. No. 4.

- Imamifar S. N., 2009. Applied Semiotics // Book of Moon Art. No. 135. P. 4-17.

- Jamshidi I., 2013. Symbol // Journal of Literature and Languages. The Growth of Persian Language and Literature Education. Spring 92. No. 105.

- Khazaee M., 2007. The imprint of symbolic motifs of Peacock and Simorgh in Sa-favid era buildings // Visual Arts. July, 26. P. 24-27.

- Motavali M., 2013. Study of the form and content in the designs of tombstones in the cemeteries of Mazandaran province (case study of tombstones of the cemetery of Chahsafid in Behshahr city): Master's thesis. Ministry of Science, Research and Technology, Payame Noor University, Payame Noor University of Tehran Province, Faculty of Arts and Architecture.

- Nobakhti Xiyavi S., 2001. Lost Xiyav from the history. Tehran: Ghoo Publication.

- Pahlavan F., 2006. An introduction to the Analysis of Elemental Images, Tehran: Art University.

- Peirce C. S., 1931-58. The Collected Papers. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Harvard.

- Pouriman Gh., 2001. Neginsabz of Azerbaijan (Meshginshahr). Tehran: Moshiri Publishing.

- Rismanchian O., HeidariM., 2005. "Water, Symbol, Desert": Scientific Confer-ence of Kavir Architecture Areas, Islamic Azad University of Ardestan.

- Sajjadi A., 1993. The series of evolution of the altar in the Islamic architecture of Iran from the beginning to the Mongol invasion: Master's thesis on archeol-ogy. Faculty of Humanities, Tarbiat Modarres University.

- Sajjadi J., 1996. Dictionary of mystical terms. Tehran: Iranian language and cul-ture.

- Shayestehfar M., 2009. Decorating the inscriptions of Sheikh Safi tombstones and adapting them to Naharkhoran of Gorgan // The Art Book Monthly. No. 134. P. 74-81.

- Shayestehfar M., 2010. Symbol of the basis of aesthetic and thematic studies of art // The Art Book sheet. No. 139. P. 94-109.

- Tafazoli A., 1997. Qibla of Mosque View, Mihrab // Islamic Studies Magazine. No. 35 and 36. Architecture Goljam. No. 12. P. 99-112.

- Widengren G., 1999. Religion of ancient Persia / Transl. by Manouchehr Farhangi. First Edition. Tehran.

- Yahaghi M. J., 1996. The Culture of Myths and Fictional refering in Persian Litera-ture. Tehran: Soroush.