Island communities’ viability in the Arkhangelsk oblast, Russian Arctic: the role of livelihoods and social capital

Автор: Olsen Julia, Nenasheva Marina V., Hovelsrud Grete K., Wollan Gjermund

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 42, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, local communities have been adapting to new political and socioeconomic realities. These changes have prompted dramatic outmigration among rural populations, es-pecially in the Russian Arctic. Despite these changes, some communities remain viable, with some residents exploring new economic opportunities. This study uses findings from qualitative interviews to understand what factors shape community viability, interviewing residents and relevant regional stakeholders in two case areas in the Arkhangelsk oblast: the Solovetsky Archipelago in the White Sea and islands in the delta of the Northern Dvina River. The results indicate that community viability and the reluctance of community mem-bers to leave their traditional settlements are shaped by livelihoods, employment opportunities, and social capital. Social capital is characterized by such empirically identified factors as shared perceptions of change and a willingness to address changes, place attachment, and local values. We conclude that further develop-ment or enhancement of community viability and support for local livelihoods also depends on 1) bottom-up initiatives of engaged individuals and their access to economic support and 2) top-down investments that contribute to local value creation and employment opportunities.

Arctic, Arkhangelsk oblast, community viability, livelihoods, social capital

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318343

IDR: 148318343 | УДК: [364-785.14:332.012.23](470.11)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2021.42.13

Текст научной статьи Island communities’ viability in the Arkhangelsk oblast, Russian Arctic: the role of livelihoods and social capital

This explorative study aims to examine the factors that shape island communities’ viability and residents’ willingness to stay in said communities during periods of multiple changes. The collapse of the Soviet Union prompted dramatic changes in political, economic, and social conditions in Russia and, especially, its Arctic areas. Declining living standards and quality of life, the closure of vital social services, increasing unemployment, aging infrastructure, and high outmigration are just some of the consequences of the socioeconomic transformation faced by the Arctic population since the early 1990s [1, Artobolevsky S.S., Glezer O.B.]. The transition to a market economy led to the loss of state subsidies and the closure of many collective and state farms, social services, and industries [1, Artobolevsky S.S., Glezer O.B.]. The absence of this crucial economic support has challenged the

viability of rural settlements, resulting in high outmigration to larger towns and cities and from north to south [2, Heleniak T., pp. 81–104].

Over the past 30 years, Russia’s rural population has decreased from 39.1 million in 1989 to 36.3 million in 2018 [3, Zakharov S.V.]. Climate change is another challenge affecting small, local communities and their livelihoods and socioeconomic development in the Russian Arctic. Recent studies from the Barents region report changes in the cryosphere, increasing precipitation and temperatures, and changes in the distributions of floral and faunal species [4, AMAP; 5, AMAP]. Changes in river and ocean ice conditions have extended the navigation season for water transportation, with implications for local mobility [6, Dumanskaya I.O.; 7, Mokhov I.I., Khon V.C.; 8, Olsen J., Nenasheva M.; 9, Vorontsova S.D.]. The same changes have shortened the operation period for winter and ice roads [10, Prowse et al.], which are sometimes compromised by sudden melts during milder winter temperatures over long periods of time. Ice roads represent vital transportation and supply infrastructure during winter, as they connect various Arctic communities [11, Olsen J., Nenasheva M., Hovelsrud G.K.].

Since the 1990s, the community viability of Russian Arctic settlements has been shaped by multiple interrelated changes, many of which are exaggerated by shifting climatic conditions. Despite these socioeconomic, demographic, and environmental changes, people are willing to stay in Russia’s small Arctic communities, dealing with the changes and engaging with or exploring new opportunities for local socioeconomic development. To examine this phenomenon, our study builds on the concept of community viability [12, Rasmussen R.O., Hovelsrud G., Gearheard S.] to examine what factors support and shape community viability in two island communities in the Arkhangelsk oblast. The case communities are located on the Solovetsky Archipelago in the White Sea and on islands in the delta of the Northern Dvina River. Our empirical data derive from interviews with residents in both areas and is supported by interviews of key regional stakeholders in Arkhangelsk.

Study approach

By studying rural island communities, we can examine factors of community viability connected to a community’s surrounding environment and to interactions between inhabitants. Community viability refers to a community’s ability to stay viable in the context of ongoing changes. Aarsæther, Riabova, and Bærenholdt [13, Aarsæther N., Riabova L., Bærenholdt J.O., p. 139] describe a viable community as “one in which people feel they can stay as inhabitants for a period of their lives, where they find sources of income and meaningful lives.” The Arctic Human Development Report [14, TemaNord] showed that community viability is related to everyday security needs, socioeconomic and environmental concerns, and the ways in which settlements are developed and maintained [12, Rasmussen R.O., Hovelsrud G., Gearheard S.]. The scientific literature views community viability as connected to economic and financial viability and/or residents’ willingness to live in a specific settlement. Economic and financial viability are studied, for example, in communities in which a cornerstone industry plays a central role in the accumulation of capital and, hence, the in- creased attractiveness of the community. When referring to residents’ willingness to stay at a specific settlement, existing studies refer to residents’ future perspectives about staying [15, Munkejord M.C.] and describe several subjective motivation factors 1. The same studies specify that these motivation factors vary across communities. For example, using survey results in one Norwegian municipality, Sørlie 2 argued that job opportunities are the main motivations to live in smaller communities. In addition to job opportunities, place attachment, local environment, social networks, and the ability to influence local decision-making are important factors 3 [16, Hovelsrud G.K., Karlsson M., Olsen J.].

Though the topic of viability of Arctic communities has received attention in the literature, the factors that shape such viability remain underexplored. Viability can be approached as a dynamic phenomenon, since communities undergo a process of continuous change and are influenced by numerous dynamic factors, including social capital. The linkages among social attributes and community viability have not been broadly investigated. In the study of rural communities in the Alpine region, Wiesinger [17, Wiesinger G., pp. 43-56] argued some communities lacking policy support and economic performance could still be more viable than others. Furthermore, Wiesinger [17, Wiesing-er G., pp. 43-56] argued strong social ties allow inhabitants to live vibrant lives, even in communities with unfavorable socioeconomic conditions.

Such strong social ties and networks are related to communities’ social capital, or the valued resources that generate return to individuals and collective groups in society and that are captured in people’s social relations [18, Mitra J.]. Social capital also relates to the ability to act collectively to address changes [19, Adger N.] According to Bourdieu’s empirical approach [20, Broady D., pp. 177– 179], social capital exists only if it is activated: that is, if the relations to others (e.g. kinship and friendship) are real and can be converted into other forms of value or capital (e.g. economic or cultural). According to Lin [21, Lin N.], social capital cannot be possessed by individuals; rather, valued resources are embedded in networks themselves and are accessible through direct and indirect ties. What matters are not only the specific social relationships among individuals, but also those social linkages forged in relation to specific places. Such social links may include formal and informal organizations (e.g. the workplace or volunteerism) in local communities. In this study, we examine the relations between a community’s quantifiable assets and its actual viability, adopting a communitybased approach to empirically explore stakeholders’ perspectives and responses to changing ongo- ing conditions [16, Hovelsrud G.K., Karlsson M., Olsen J.; 11, Olsen J., Nenasheva M., Hovelsrud G.K.] and examine the factors that shape the viability of island communities.

Case area

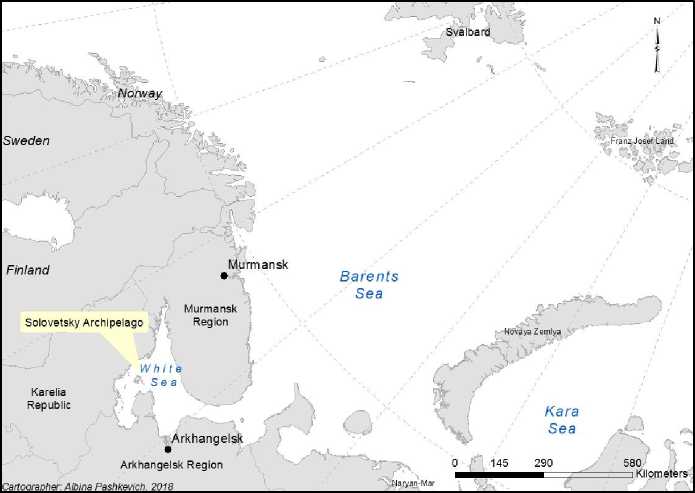

To examine whether and how small rural communities in the same region (i.e. the Arkhangelsk oblast) perceive and respond to changes and what factors enhance viability, two cases were selected. This qualitative case study was conducted in two island areas: the Solovetsky municipality on the Solovetsky Archipelago and island communities in the municipalities of Ostrovnoe and Oktyabr’sky, situated in the Northern Dvina River delta. The populations in both case areas have experienced dramatic changes in their socioeconomic conditions since the end of the Soviet period, exaggerated by changes in sea/river ice conditions [8, Olsen J., Nenasheva M.; 11, Olsen J., Ne-nasheva M., Hovelsrud G.K.]. Due to their geographic situation, the populations of the island settlements have limited mobility and connectivity with the mainland. During the ice-free period, both case areas can be reached by water transportation. During the winter period, the communities in the delta of the Northern Dvina River have ice road connections to Arkhangelsk, while Solovetsky is approachable only by plane. There is no land-based infrastructure (e.g. bridges) connecting the island communities with the mainland. The main characteristics of the case communities are highlighted in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Map of the study area with adjustment territories.

During the Soviet era, the municipality of Ostrovnoe produced agricultural products for Arkhangelsk. The island also held a space research station, an airport, and a number of social services used by both the settlements and the population of Arkhangelsk. Home to the Solovetsky Monastery, the Solovetsky Archipelago— Solovki , in Russian—has a rich history, powerful culture, and unique wildlife composition that have attracted tourists for decades. Though the number of domestic and international tourists to the archipelago has increased in recent years [8, Olsen J.,

Nenasheva M.], the community experienced more tourists during the Soviet era, when a regular cruise route ran between the archipelago and Arkhangelsk [22, Maksimova T.].

Table 1

The main characteristics of the case communities 4

|

Characteristics |

Ostrovnoe/Oktyabr’sky |

Solovetsky |

|

Geographic location |

64 °N; the Northern Dvina River delta, Arkhangelsk oblast, Russia |

65 °N; Solovetsky Archipelago (also known as Solovki), White Sea, Arkhangelsk oblast, Russia |

|

Major settlements |

Pustosh, Vyselki, Odinochka, Adriano-vo, Voznesenye, Konezdvorye, Lastola |

Solovetsky is a transportation and administrative hub for the Solovetsky Archipelago |

|

Demography |

1,896 native Russian inhabitants. The population is declining. |

943 primarily native Russian inhabitants, 10% of whom are monks. The population remains stable. |

|

Employment |

Museums, municipality, tourism, agriculture, and the subsistence economy |

Museum, monastery, municipality, tourism, and the subsistence economy |

|

Transport linkage with the mainland |

Shipping (seasonal) and winter roads |

Shipping (seasonal) and air transportation (year-round) |

|

Natural environment use |

Fishing; collecting wild plants; recreation; agriculture |

Recreation; fishing for subsistence and private income (year-round); collecting local resources (berries, mushrooms, seaweed) for subsistence during the summer season |

Methods

We apply a community-based approach [23, Hovelsrud G.K., Smit B.; 24, Kelley K.E., Ljubicic G.J., pp. 19–49] to understand local communities’ perspectives on the changing conditions and local factors that constitute community viability. Community-based approaches are broadly used in adaptation studies. These approaches facilitate engagement of relevant stakeholders and community residents to examine local perceptions of change, exposure-sensitivity, capacity to adapt to change, and whether and how the community responds to said changes [25, Smit B., Hovelsrud G., Wandel J., Andrachuk M., pp. 1–22]. In this study, we worked closely with community members and/or relevant stakeholders during the preliminary fieldwork and during the data collection period. This allowed us to increase the relevance of the study to residents’ needs and changing conditions, and also to explore local perspectives in-depth, adapting to concerns and response strategies regarding on-going changes.

Our empirical data comprise interview and observation data collected by two members of the author team during fieldwork in the case areas: first, in Solovetsky in June 2017, and later, in the Northern Dvina River delta communities in June 2019. Additionally, interviews were conducted in Arkhangelsk, with key stakeholders representing local and regional officials and industrial representatives who influence and support the development of island territories in the Arkhangelsk oblast (Table 2). Some of these stakeholders can be also described as links between local and region-

4Number of residents of Municipality “Ostrovnoye". Arkhangelskstat, 2019. Date of request: 10.10.2020; Solovetsky Strategy. (2013). Development Strategy of Solovetsky Archipelago as a unique site of spiritual, historical-cultural and natural heritage. URL: (accessed 20 December 2020).

al levels, as they share knowledge on island communities’ current and future development and are often the first contacts for community members working to address local concerns.

Some of the interviewees in both municipalities were identified and contacted prior to the primary fieldwork stage to organize and schedule interviews. However, due to the low number of residents and the limited ability to contact the local population in advance, we applied standard “snowball” sampling methods, in which the respondents themselves suggested other potential candidates to interview [26, Blaikie N.]. To secure the interviewees’ anonymity, we use a coding system for citation purposes: interviews A1 through A32 represent the Ostrovnoe case, and interviews S1 through S24 represent Solovetsky.

Table 2

The number and types of interviews

|

Type of interview |

Interviewees involved in the study |

|

|

Ostrovnoe/ Oktyabr’sky A1-A32 |

26 personal interviews with residents of the island villages (The major part are from Os-trovnoe municipality) |

24 residents of the villages 2 former residents who still have property in one of the villages and visit it during the summer navigation season |

|

6 personal interviews with relevant stakeholders in Arkhangelsk |

1 public body 5 private and state-owned businesses |

|

|

Solovetsky S1-S24 |

12 interviews with residents 12 interviews with relevant stakeholders in Arkhangelsk |

12 residents in Solovetsky with knowledge about local socioeconomic development and the tourism industry. 12 stakeholders in Arkhangelsk with knowledge about socioeconomic development of the Solovetsky Archipelago including private and state-owned businesses |

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to examine the interviewees’ perspectives on the changing conditions and elements in their communities’ social capital that enable adaptation. The interview questions were grouped into the following categories: 1) background, 2) changing conditions, 3) local impacts, and 4) local responses. Most interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. To accomplish this, we utilized qualitative data analysis software (NVivo) and applied thematic analysis: a method identifying patterns in qualitative data [27, Braun V., Clarke V., pp. 77–101]. We coded our empirical material using codes identified (inductively) during the analysis and not theoretically guided. Then, we grouped the codes under four main categories that we used to structure our results and discuss their relation to community viability. This allowed us to capture the essence of each thematic area from the empirical data.

The materials obtained during the fieldwork were supplemented by secondary data, such as historical and modern-day development records of the islands, statistical information and information about navigation to and from the communities.

Results

Our analysis of the empirical data revealed four categories pertaining to community viability. This section provides insights into those four categories, beginning with a description of the local livelihoods and employment opportunities influenced by the changing socioeconomic and environmental conditions following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The livelihood description is followed by a presentation of local factors illustrating the motivation to stay in local communities. Of particular importance are a shared perception of changing conditions affecting local livelihoods, place connection, and local values (e.g. remoteness and social bonds).

Local livelihoods and employment opportunities

In past centuries, traditional livelihoods in the island population have been connected to the river and marine environment through fishing activities, hunting, and the gathering of wild plants (e.g. berries and mushrooms). During the Soviet era, island communities in the delta of the Northern Dvina River were engaged in agricultural activities and employed in state social services located on the islands. The main means of transportation among the islands were, and still are, passenger vessels and small boats (e.g. small rowing boats and/or motorboats), which are used for local mobility, fishing activities, and recreational purposes (A5, A11, A12). Small boats are an important part of local livelihoods and mobility in Solovetsky, where they are also used for tourism-related activities (S24).

The tourism industry on the Solovetsky Archipelago is several decades old and influences many aspects of local socioeconomic development. Solovetsky is one of the main tourist attractions in the Russian North, offering cultural, historical, natural and religious sites, including the Solovetsky Monastery (Fig. 2). Because of the monastery, pilgrims are among the archipelago’s main tourism segments. In addition, Solovetsky is visited by domestic and international individuals and tourist groups (S19, S17, S12), most of which arrive on passenger and cruise vessels during the summer. Given the proliferation of tourists, most residents provide tourism-related services, earning extra income during the summer through one or more tourist services. One resident emphasized that “every second, or even more, resident of Solovki is involved in tourism. Someone fishes, rents out a hotel, someone rents out an apartment… someone transports people” (S19). However, one of the main concerns relating to tourism development is the impact of a growing number of tourists, a topic about which the interviewees held several opinions. The stakeholders in Arkhangelsk operate with an official number of registered tourists that might be lower than the actual count and suggested that the number of tourists increases. Alternately, the residents of Solovetsky experienced negative impacts on the local environment and infrastructure and suggested that the number of tourists visiting the archipelago should be more regulated (e.g. S12, S17).

Fig. 2. The Solovetsky Monastery, the main tourism attraction of the Solovetsky archipelago5.

Compared to Solovetsky, tourism development is a rather new industry for the municipality of Ostrovnoe (one of the island communities) and is mostly driven by residents who have received grants to establish tourist services (e.g. A5, A18, A30). One interviewee informed us that one of the villages hosts about 1,000 domestic and international tourists per year (mostly during the summer), but that only a few residents are employed in tourism-related activities (A18). A resident from another village emphasized that the number of tourists has increased since the opening of a local museum and that “life has become more eventful. The influx of tourists to the village plays a big role” (A30). Currently, tourists can visit two museums: a space museum that presents a history of the Soviet research station and a sea pilot museum covering the history of Arkhangelsk, the first port in Northern Russia (e.g. A13, A14, A30). The residents also discussed other products of tourism, such as a new café and organized bicycle trips (A2), as well as weekend tours, including an excursion into the village for school and church visits (A30). One resident identified potential for building guest houses (A23), while those engaged in tourism suggested that further tourism development will depend on marketing (A18, A31). In this context, Solovetsky can serve as a kind of warning of what could happen when island communities experience a higher influx of tourists, since the residents on Solovetsky already report an excessive number of tourists due to unregulated individual tourism (S15, S19).

Finally, agriculture is another form of local livelihood in the Ostrovnoe municipality. It was the dominant livelihood during the Soviet era, but only a fraction of residents currently practice it (A15). One resident remembered that, “before the collective farm collapsed, everyone had work here, nobody [moved to another place], children studied at school, there was a tractor-driving

5 Photo: Julia Olsen, June 2017.

class, people moved here from other places, we had a population influx, we produced milk and butter, and we fed [Arkhangelsk] with potatoes” (A 14). Several residents reflected on the potential of rebuilding the island’s agricultural industry; however, this development might be jeopardized by changes in the navigation season, which have already created numerous challenges for agricultural transport between the island territories and Arkhangelsk, especially during the rasputitsa 6 season (A29).

Shared perception of changes

Most residents in rural communities, especially in the Northern Dvina River delta, are concerned about local socioeconomic development and emphasize that the settlement population has been declining since the end of the Soviet era, with outmigration driven primarily by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the consequent shutdown of local industries and community services. The respondents in both municipalities were nostalgic for the “old days” (the Soviet period), when the islands’ production and social infrastructure were better developed. One Ostrovnoe interviewee compared current development with the end of the Soviet period as follows: “I came here thirty years ago. Kindergarten worked here, we had a sanatorium, there was a boarding school. I never thought that would change" (A23). The interviewee added, “our islands are dying.”

Both case areas are characterized by a lack of opportunities for higher education. Hence, younger residents move to other cities and towns for education, and, when finished, do not necessarily return due to a lack of skilled jobs. The permanent residents of Ostrovnoe/Oktyabr’sky are concerned by the lack of employment opportunities, which forces the working population to commute to Arkhangelsk. Young people have moved or are planning to move to cities because, according to one respondent, “there is nothing here… nothing for us and the children to do” (A10). An interviewee who did not work in Arkhangelsk said, “I like to live here with my child since I do not have to travel to the city and it is quiet on the island” (А5).

Given these realities, the demographic trend in Ostrovnoe is characterized by a consistent decline and aging of the population. Pensioners prefer to stay on the islands because, as one respondent said, “I have nowhere to go” (A11). An elder interviewee said, “I like it here. I don’t need to go to the city. I might go sometimes but, in the evening, I want to go home. It’s good here. We go out, sit together. We go to our cultural house” (A16). Unlike the population in Ostrovnoe, the population of Solovetsky remains stable. The main employers on the Solovetsky Archipelago are the Solovetsky Monastery, the museum, and the local municipality. However, similar to Ostrov-noe/Oktyabr’sky, Solovetsky’s youths tend to move to other, larger cities for higher education. Some of them return for a summer period—the tourism season—which provides opportunities for extra income (S15, S17).

In addition to thinking about the population’s outmigration, residents in both communities reflected on changes in navigation seasons, which are becoming more unpredictable. They observed that the sea ice on the White Sea and the river ice on the Northern Dvina River freeze later, making it difficult to plan for the opening of the navigation season. These changes affect local mobility (S24, S15) and transportation connections with Arkhangelsk (A7, S17). However, while daily mobility in the delta of the Northern Dvina River depends on ice conditions, a year-round connection has been established among settlements via ice roads, tugboats, and passenger vessels. The mobility options of the Solovetsky population are quite different. Except for air travel, the Solovetsky residents do not have a connection to the mainland for months during the winter navigation period. This limitation affects local food security; however, the local population is used to these conditions and values the period of isolation (see section: Local values).

Connection to place

Most island residents in Ostrovnoe/Oktyabr’sky were born and raised on the islands. Some respondents initially moved away from the villages, but later returned because the villages were their “parental homes,” which they did not wish to lose. One resident described this connection to place as follows: “I was born in this house and I’ll die here” (A3). Another said, “I was born here. My parents are from here. I moved away and then returned. It does not matter where you move, you’ll return to your homeland” (A14, also A15). Several respondents who chose to keep living on the islands said that they were used to local conditions (e.g. A2, A19, A2), despite the lack of prospects for the villages’ socioeconomic development (A15). At the same time, those individuals who were actively engaged in local socioeconomic development were also former or current island residents who sought to explore the community’s economic potential and increase its social attractiveness (see section: Local livelihoods and employment opportunities).

Locals and seasonal workers in Solovetsky also mentioned a connection to place. Locals who were born in Solovetsky and had been living there for many years expressed their connection by calling the place Nashi Solovki (“Our Solovki”) (e.g. S15, S21). The younger population mentioned place connection, coupled with local economic opportunities, as their reason to return to the community, at least during the tourist season. As one resident reflected, “I like it here in the summer and fall, but I do not think that I will live here until old age. Winter is the most difficult period; there is not enough communication or social activities, and having lived in the city, there is something to compare [the rural community to]. But many come back… they come with their families, meaning that this life attracts some. If the living conditions were better here, many would be drawn back” (A21).

Seasonal workers employed in tourism-related companies tend to return to the community during the tourist season to earn extra income and experience the place. One seasonal summer worker on Solovetsky described the place connection as a process of “osoloveli:” that is, becoming local or becoming a part of Solovki. He explained, “I became a part of this place that is called osolovel” (S18).

Local values: Remoteness and social bonds

Given the remoteness of the two municipalities due to their island location and limited accessibility, the locals characterized their small communities as quieter, calmer, and safer than larger cities and towns. The residents of Ostrovnoe described the local conditions as follows: “It is quiet here, and the air is clean” (А28). Those with small children also valued that it was quiet there (A5). Cleaner environments and closeness to nature are other important benefits of the islands’ remoteness. “The air is clean here. I get headaches in the city, but not here” (А11). The natural environment comprises an important part of local food security, as many residents engage in fishing and the gathering of berries and mushrooms. “The forest and the sea will save us” (S20), emphasized a Solovetsky interviewee, while residents of Onstrovnoe stated, “We are fishers and we go fishing” (A14) and hunting (A12).

Fig. 3 Local communities value remoteness, quietude, and the natural environment. A street in a settlement of the Ostrovnoe municipality 7.

Solovetsky has infrequent transportation links with the mainland outside the tourism season, when passenger vessels stop operation (S19) and only air transportation remains. As one interviewee informed us: “We depend entirely on the navigation, since, for most of the time, we are cut off from the mainland. In winter, the planes fly two to three times a week if the weather allows” (S21). This quiet winter season is an integral part of local lives and the local religious community.

The remoteness and isolation of the communities encourage additional social bonds. As one Solovetsky resident described: “People help each other often here” (S20). In Ostrovnoe, a responded reflected, “I got used to people here. Everyone helps you” (A27). Moreover, due to the small sizes of the communities, information about topics of concern spreads fast. For example, when speaking about cruise tourist visits, one resident in Solovetsy mentioned that “nobody really informs us about it, but everyone knows anyway” (S15).

7 Photo: Julia Olsen, June 2019.

Discussion: Current socioeconomic development

Despite the dramatic changes prompted by the collapse of the Soviet Union, outmigration, changes in climatic conditions and the navigation seasons, residents continue to remain in the Solovetsky and Ostrovnoe communities, engaging in local socioeconomic development and managing the changes that affect local livelihoods. The empirical results indicate that our case communities build community viability via sustained livelihoods, employment opportunities (e.g. tourism) and factors that form social capital. These factors include shared perceptions of change, connection to place, and local values (e.g. remoteness and social bonds). Such factors are not formed individually, and meaning is created when local communities develop formal and informal social ties [21, Lin N.]. These dynamic factors manifested in each of the case areas, but received diverse interpretations due to differences in context.

The literature describes ‘livelihoods’ as the types of activities in a specific community, that refers to the means of securing the necessities of life 8 and “comprises the capabilities, assets (stores, resources, claims and access) and activities required for a means of living”[28, Chambers R., Conway G., p. 6]. Hence, the concept of livelihoods is closely related to viability [12, Rasmussen R.O., Hov-elsrud G., Gearheard S.]. This relationship between community viability and local livelihoods is also described in the results section, where we argue that a viable community is one that is able to sustain, adapt, or transform local livelihoods in the face of changing conditions. Despite economic stagnation, locals on Ostrovnoe / Oktyabr’sky believe in the possibility of economic adaptation and social rebirth through the exploration of new types of livelihoods and the attraction of new employment opportunities, such as tourism. On the other hand, a loss or decrease in a key livelihood, such as farming, deeply affects community viability. The shutdown of state farms in the 1990s led to a dramatic decrease in agricultural activities, resulting in outmigration and reduced food security in Os-trovnoe. The community of Solovetsky is working to develop and sustain its tourism economy, which has been reshaped since the 1990s. Sufficient transportation options (e.g. water transportation) between the island communities and the mainland were described as crucial for local development and the tourism industry, since most tourists come to the communities on passenger vessels [11, Olsen J., Nenasheva M., Hovelsrud G.K., pp. 1–19; 8, Olsen J., Nenasheva M., pp. 241–261]. These passenger vessels are used by both locals and tourists and, hence, play a crucial role in community viability.

Communities’ social capital is rooted in local initiatives and high social integration [29, Borch J.B., Førde A.] and is linked to place via the ways in which people communicate and mobilize resources for the benefit of the local community. Hovelsrud et al. [16, Hovelsrud G.K., Karlsson M., Olsen J.] identified several factors that comprise social capital in Norwegian communities, including social networks and trust, place attachment, local and experiential knowledge, engaged individuals, and perceptions of risk. Our case communities exhibited two of these factors: a shared perception of change and connection to place. The community’s values, however, add new insight to the examination of social capital and viability. The following discussion reflects on local interpretations of these factors, which are summarized in Table 3.

A shared perception of change , which is linked to a shared perception of risks, is a socially constructed factor affected by worldviews, values, and beliefs [16, Hovelsrud G.K., Karlsson M., Olsen J.]. Moreover, a shared perception is linked to the nature of a community’s social ties, which our empirical data show are formed though networks rooted in village history and people’s memories. The histories of the case villages date back to the 14th century, and memories about the past (i.e. the Soviet era) influence community perceptions of changing conditions and local impacts. Visions of community development are supported by memories of well-functioning village systems.

The literature describes connection to place as the emotional ties to a meaningful location that facilitate social relations and form identity [30, Relph E.; 31, Tuan E.F., pp. 211–252]. This study illustrates that place attachment is a central aspect of social capital in viability creation. In line with Hovelsrud et al. [16, Hovelsrud G.K., Karlsson M., Olsen, J.], we argue that place connection is a motivating factor for handling changing conditions [32, Olsen J., Hovelsrud G.K., Kaltenborn B.P., pp. 305–331]. The villagers that remain in the case municipalities are deeply attached to their communities, to maintaining their livelihoods, and to exploring new economic opportunities. We have observed similar place connections among the key regional stakeholders in Arkhangelsk, who are linked to one or the other of the case areas and express an interest in development. The individuals attached to the villages in Ostrovnoe have lived there all their lives, grew up there and then moved away, or moved away and then bought property in the villages to move back to or visit. For these individuals, the place means home, and it is often associated with care, belonging, attachment, and rootedness [30, Relph E.; 31, Tuan E.F., pp. 211–252].

Individuals without previous connections to Solovki describe the process of becoming emotionally tied to the place as “becoming a part of the place.” This example illustrates that place attachment is a dynamic factor in modern society that can apply to more than one location [33, Haugen M.S., Villa M.]. We could argue that place attachment activates a community’s willingness to deal with changes and enhance local socioeconomic development. In Ostrovnoe, this enhancement is also related to the memory of the Soviet era, which was characterized by more residents and better living conditions.

Local values are connected to local culture and comprise contextual aspects that are important for community viability. The values in this study are empirically identified factors described by Wolf, Allice, and Bell [34, Wolf J., Allice I., Bell T., p. 548] as “trans-situational conceptions of the desirable that give meaning to behaviour and events, and influence perception and interpretation of situations and events.” Despite the apparent similarities in values between the case communities, the meanings of these values vary greatly, even within the same region. In our study, both case communities valued remoteness, quietude, and proximity to nature. This corresponds with findings made in the Norwegian High North by Ween and Lien [35, Ween G., Lien M.], who argued that na- ture is a reason for both staying and moving away. While remoteness and quietude on Solovetsky refer to a period of isolation without tourists, remoteness for the populations of Ostrovnoe and Ok-tyabr’sky refers to the distance between these communities and the urban setting of Arkhangelsk.

In addition to remoteness, residents in the case communities emphasized having particular social bonds and communication methods that differ significantly from those that take place in urban culture. In small communities, close social interactions clearly influence several aspects of inhabitants’ lives. Small communities are characterized by “openness” in communication, since everyone’s personal life is largely visible. The community consciousness is formed by a “transparency” in behavior that is influenced by members’ opinions and assessments.

Table 3

The factors of social capital that influence community viability

|

Social capital |

Significance for Ostrovnoe/ Oktyabr’sky |

Significance for Solovetsky |

|

Shared perception of change |

and reduced attractiveness

to/coping with new local conditions |

present both uncertainties and possibilities

members provide tourist services

|

|

Connection to place |

cals who have moved away)

tachment |

and seasonal workers who have “become part of the place”

and seasonal workers who wish to return |

|

Local values |

|

son

|

In sum, we suggest that the elements comprising social capital are central to community viability and motivate efforts to manage ongoing changes. In line with Wiesinger [17, Wiesinger G., pp. 43–56], we argue that social capital plays a central role in enhancing the socioeconomic development of rural communities through social organization, local engagement, and closer connections to other communities and the surrounding environment. At the same time, the role of social capital should not be overemphasized, as communities’ socioeconomic developments can be weakened by further outmigration or jeopardized by new changes, such as changes in the navigation seasons.

Concluding remarks: Further development

In this study, we have examined several factors that form community viability, such as local livelihoods, economic opportunities, and social capital. Based on the results from the Ostrovnoe municipality, we argue that enhancing social capital without supportive top-down initiatives for local development can only maintain the status quo. A lack of economic opportunities, such as local employment and local value creation, can negatively affect community viability and increase outmigration. The findings illustrate that the engaged residents in both case communities see the potential in island tourism development via cultural, historical, and spiritual sites. The number of tourists is in- creasing every year, and local residents have fruitful ideas for developing tourist attractions. In Os-trovnoe / Oktyabr’sky, several projects have already been realized. We suggest that further development of rural municipalities will depend on engaged individuals who look for ways to enhance economic potential. Such initiatives may proceed from the bottom up, as in grant-based support of local initiatives, or from the top down, as in investments in rural community development. The case of Ostrvnoe / Oktyabr’sky indicates the importance of bottom-up support received by engaged residents, while Solovetsky is more dependent on top-down support combined with local engagement in residents’ tourism services.

We argue that social capital is likely a central aspect in enhancing community viability. However, to secure such viability, institutionalized initiatives that support local livelihoods and lead to local employment (e.g. greater access to economic support, investment in territorial development, and sufficient transportation options) would be beneficial. Still, investments in territorial development are challenging, and regional public bodies would need to determine what kinds of development policies and supportive initiatives to implement in communities that experience outmigration.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank participants involved in this study for sharing their meanings and valuable insights about the study topic; Malinda Labriola and Nikolai Holm for providing language help. This study received financial support from Nord University, Bodø, Norway. We are particularly appreciative of the comments by two anonymous reviewers that helped improve the paper.

Список литературы Island communities’ viability in the Arkhangelsk oblast, Russian Arctic: the role of livelihoods and social capital

- Artobolevsky S.S., Glezer O.B. Regional'noe razvitie i regional'naya politika Rossii v perekhodnyy period [Russian Regional Development and Regional Policy in Transition Period]. Moscow, MSTU named after N.E.Bauman, 2011, 317 p. (In Russ.)

- Heleniak T. Internal Migration in Russia During the Economic Transition. Post-Soviet Geography and Economics, 1997, no. 38 (2), pp. 81–104.

- Zakharov S.V. Naselenie Rossii 2017: dvadtsat' pyatyy ezhegodnyy demograficheskiy doklad [Population in Russia 2017. 25th Annually Demographic Report]. Moscow, High School of Economics, 2019, 480 p. (In Russ.)

- AMAP. Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Barents Area. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). Oslo, Norway, 2017, pp. xiv + 267.

- AMAP. Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA) 2017, Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). Retrieved from Oslo, Norway, 2017b, xiv + 269.

- Dumanskaya I.O. Ledovye usloviya morey evropeyskoy chasti Rossii [Ice Conditions of the Seas in Northern European Russia]. Moscow, Hydrometeorological Centre of Russia, 2014, 608 p.

- Mokhov I.I., Khon V.C. Prodolzhitel'nost' navigatsionnogo perioda i ee izmeneniya dlya Severnogo morskogo puti: model'nye otsenki [The Duration of the Navigation Period and Changes for the Northern Sea Route: Model Estimates]. Arktika: ekologiya i ekonomika [Arctic: ecology and economy], 2015, 2 (18), pp. 88–95.

- Olsen J., Nenasheva M. Adaptive Capacity in the Context of Increasing Shipping Activities: A Case from Solovetsky, Northern Russia. Polar Geography, 2018, no. 41 (4), pp. 241–261. DOI:10.1080/1088937X.2018.1513960

- Vorontsova S.D. Vliyanie klimaticheskikh izmeneniy na transportnuyu infrastrukturu v Arkticheskoy zone i na territoriyakh rasprostraneniya vechnoy merzloty [Influence of Climate Change on Functioning of Transport Infrastructure Objects in Russian Federation's Arctic Zone and in the Territories Affected by Permafrost]. Transport Rossiyskoy Federatsii [Transport of the Russian Federation], 2017, no. 4 (71), pp. 33–39.

- Prowse T.D., Bring A., Carmack E.C., Holland M.M., Instanes A., Mård J., Wrona F.J. Freshwater. In: Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA). Oslo, Norway, Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, 2017.

- Olsen J., Nenasheva M., Hovelsrud G.K. ‘Road of Life’: Changing Navigation Seasons and the Adaptation of Island Communities in the Russian Arctic. Polar Geography, 2020, pp. 1–19. DOI: 10.1080/1088937X.2020.1826593

- Rasmussen R.O., Hovelsrud G., Gearheard S. Community Viability and Adaptation. In: Arctic Human Development Report: Regional Processes and Global Linkages. Copenhagen, Nordisk Ministerråd, 2014, 500 p.

- Aarsæther N., Riabova L., Bærenholdt J.O. Community Viability. In: The Arctic Human Development Report. Akureyri, Stefansson Arctic Institute, 2004.

- TemaNord. Arctic Human Development Report: Regional Processes and Global Linkages. Copenhagen, Nordisk Ministerråd, 2014, 500 p.

- Munkejord M.C. Hjemme i Nord. Om bolyst og hverdagsliv blant innflyttere i Finnmark [At Home in the North. About Desire to Llive and Everyday Life of Migrants in Finnmark]. Orkana akademisk, 2011, 262 p.

- Hovelsrud G.K., Karlsson M., Olsen J. Prepared and Flexible: Local Adaptation Strategies for Avalanche Risk. Cogent Social Sciences, 2018, no. 4 (1), 19 p. DOI: 10.1080/23311886.2018.1460899

- Wiesinger G. The Importance of Social Capital in Rural Development, Networking and Decision-Making in Rural Areas. Journal of Alpine research, 2007, no. 95 (4), pp. 43–56.

- Mitra J. Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development. London, Routledge, 2012, 518 p.

- Adger N. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. Economic Geography, 2003, no. 79 (4), pp. 387–404.

- Broady D. Sociologi och epistemologi. Om Pierre Bourdieus författarskap och den historiske epistemologien [Sociology and Epistemology. About Pierre Bourdieus Authorship and the Historical Epistemology]. Stockholm, HLS Förlag, 1991, 649 p.

- Lin N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. xiv+278.

- Maksimova T. Turistskiy potok na Solovetskom arkhipelage: dinamika i sovremennye perspektivy [Tourist Flow in the Solovetsky Islands: Dynamics and Contemporary Perspectives]. Proceedings of the Festival of the Russian Geographical Society. Saint Petersburg, 2016, pp. 825–828.

- Hovelsrud G. K., Smit B. Community Adaptation and Vulnerability in the Arctic Regions. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York, Springer, 2010, 353 p.

- Kelley K.E., Ljubicic G.J. Policies and Practicalities of Shipping in Arctic Waters: Inuit Perspectives from Cape Dorset, Nunavut. Polar Geography, 2012, no. 35 (1), pp. 19–49. DOI:10.1080/1088937X.2012.666768

- Smit B., Hovelsrud G., Wandel J., Andrachuk M. Introduction to the CAVIAR Project and Framework. In: G. Hovelsrud, B. Smit, eds. Community Adaptation and Vulnerability in the Arctic Regions. Dordrecht, Springer, 2010, pp. 1–22.

- Blaikie N. Designing Social Research. Cambridge, UK, Polity Press, 2010, 352 p.

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006, no. 3 (2), pp. 77–101. DOI:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chambers R., Conway G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century. IDS Discussion Paper, 1992, 296 p.

- Borch J.B., Førde A. Innovative bygdemiljø. Ildsjeler og nyskapsingsarbeid [Innovative Rural Environment. Passionate and Innovative Work]. Bergen, Fagbokforlaget, 2010, 184 p.

- Relph E. Place and Placelessness. London, Pion Limited, 1976, 176 p.

- Tuan Y-F. Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective. In: Gale S., Olsson G., eds. Philosophy in Geography. Theory and Decision Library (An International Series in the Philosophy and Methodology of the Social and Behavioral Sciences). Dordrecht, Springer, vol. 20, pp. 387–427. DOI: org/10.1007/978-94-009-9394-5_19

- Olsen J., Hovelsrud G.K., Kaltenborn B.P. Increasing Shipping in the Arctic and Local Communities’ Engagement: A Case from Longyearbyen on Svalbard. In: E. Pongrácz V. Pavlov, N. Hänninen, eds. Arctic Marine Sustainability: Arctic Maritime Businesses and the Resilience of the Marine Environment. Cham, Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 305–331.

- Haugen M.S., Villa M. Lokalsamfunn i perspektiv [Local Communities in Perspective]. In: Villa M., Haugen M.S., eds. Lokalsamfunn. Oslo, Cappelen Damm, 2016.

- Wolf J., Allice I., Bell T. Values, Climate Change, and Implications for Adaptation: Evidence from Two Communities in Labrador, Canada. Global Environmental Change, 2013, no. 23 (2), pp. 548–562. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.11.007

- Ween G., Lien M. Decolonialization in the Arctic? Nature Practices and Land Rights in the Norwegian High North. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 2012, no. 1, pp. 93–109.