Issues of the work and family activities of the older generation

Автор: Vasilyeva E.V.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 5 т.18, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article analyzes the trends and socio-economic conditions of the transformation of the grandmother institution in Russia. The research employs the theoretical framework of neoclassical theory and neo-institutionalism, which explain the nature of the grandmother institution. A system of indicators describing the demographic characteristics of the population and its behavior has been developed. The data from the Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat) served as the information base for the study. The analysis was conducted from the perspective of all participants: grandparents (the “grandmothers” themselves), parents, grandchildren, and the state as an actor shaping the environment in which the grandmother institution functions. The study has shown that the grandmother institution is transforming, adapting to new socio-economic conditions while retaining its significance. On the one hand, older people have become more in demand in the economy and society. There is a significant increase in the employment of the elderly population, especially among women aged 55–59. On the other hand, grandparents have become even more active in the lives of their grandchildren. The proportion of grandmothers providing daily childcare increased from 22.2% to 32.2%, and that of grandfathers from 13.2% to 23.4%. This is explained by an increase in the number of single-parent households with children (from 13.0% to 21.1% of all households with children), as well as an increase in the employment of women with children (from 76% to 82.8%). The results of Russian sociological surveys reveal the institutional nature of the motivation for the elderly population's participation in grandchild care. Sacrificial attitudes are characteristic of the majority of respondents; however, this position is not supported by parents, who prefer to raise their children independently and turn to grandparents only when assistance is required

Grandmother institution, population aging, employment, elderly population, households, women

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147252467

IDR: 147252467 | УДК: 331.522+314.146 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2025.5.101.9

Текст научной статьи Issues of the work and family activities of the older generation

Modern concepts of “active aging” and “a society for all ages” significantly revise and expand the trajectories of aging. A new approach has been established in scientific discourse on older people, according to which public policy ensures their participation in all spheres of social life (Grigoryeva, Kelas’ev, 2016). The socio-economic context of such changes in the social and interfamilial roles of older people includes increased life expectancy and career length, nuclearization of families, urbanization, improved living standards and quality of life, and the development of social infrastructure. As rightly noted in an expert analytical report by the ANO “National Priorities”1, given the changing age structure of the population and the growing demand for the labor force in the Russian economy, representatives of the older generation are becoming one of society’s key resources. However, the traditional role of the older generation in the family, associated with caring for the younger generation, retains its significance. The overlap of these trends forces the older generation to choose between selfrealization in society and fulfilling their traditional role in the family. As a result, the grandmother institution, characterized by an older woman taking care for her grandchildren, is being significantly transformed and even gradually falling into disuse (Sorokin, 2014; Rimashevskaya, 2003). This research attempts to analyze the trends and socio-economic context of the transformation of the grandmother institution in Russia, as understanding the motivation and challenges of the older generation will help optimize the interaction between the institutions of the labor market, social security, and family, which is particularly important in the context of ensuring sustainable development of Russian society. To achieve this goal, three objectives are formulated: first, to review theoretical approaches explaining the behavioral models of the older generation in the context of their social activity, including participation in social life and fulfilling the family role of grandparents; second, to develop an approach for researching the transformation of the grandmother institution based on the analysis of statistical data on indicators characterizing the demographic and socio-economic context shaping the behavior of all participants in these relationships; third, to identify patterns and established trends in the development of the grandmother institution in Russia using the proposed approach.

Theoretical framework of the research

In this study, the grandmother institution is understood as a stable form of organization of the activities of the family’s older generation – grandparents – who perform functions of parents (part of them) in caring for and raising the younger generation – their grandchildren. Considering the feminization of aging and the gender distribution of roles within the family, this institution is primarily formed by women, but men can also fulfill these functions; therefore, the research concerns representatives of both men and women among grandparents, i.e., grandmothers and grandfathers.

Within the framework of the neoclassical school, two models have been developed to explain the distribution of family resources: Samuelson’s consensus model and Becker’s altruist model. The first model is based on the hypothesis of a permanent “family consensus”, which is a reconciliation of interests or compromise of family members. P.A. Samuelson explains the consensus in the preferences of family members by kinship (“blood is thicker than water” (Samuelson, 1956), so the family acts as if it maximizes its overall welfare function (group preferences). According to models of generational economics (Lee, 1980; Lee, 2007; Lee, Mason, 2014), interfamilial relations involve the redistribution of resources (finances, time, etc.) between family members, the economic mechanism of which is intergenerational transfer. The defining feature of such a transfer is the absence of an explicit “something in exchange for something” (quid pro quo)2.

In G. Becker’s altruist model, the “group preference function” is identical to the function of the altruistic parent, even if this parent does not possess sovereign power in the family. “Optimal redistribution” of income results from altruism and voluntary contributions. The altruist feels better from actions that increase their family’s income and worse from actions that decrease it. Therefore, the altruist will refrain from actions that increase his or her own income if they further decrease the family’s income; and the altruist will undertake actions that reduce his or her own income if they further increase the family’s income (Becker, 1991). According to G. Becker, the time allocation of any family member is strongly influenced by the opportunities available to other members (Becker, 2003). Altruism within the family is confirmed by the fact that parents, sacrificing their own consumption and comfort, spend money, time, and effort on children, investing in their human capital. But even altruistic parents must seek a compromise between their own consumption and their children’s human capital. Moreover, in modern societies, kinship is less significant than in traditional societies, where a significant portion of time and other resources is invested in children by grandmothers, grandfathers, aunts, and other relatives concerned with their wellbeing and behavior (Becker, 2003). The growth of state and private programs in education, healthcare, and social assistance has weakened the bonds between family members by eroding its traditional role in protecting its members from various risks. Relatives not only lose interest in monitoring and controlling family members, but their ability to do so diminishes as family members disperse in search of better opportunities.

Neoclassical school models view the economic agent as a rational individual aimed at efficiently allocating limited resources. Institutionalism demonstrates that the spectrum of household incentives is much broader. According to H. Simon, human rationality is bounded by the unavailability of all possible information and their ability to process it; therefore, they do not seek to choose the best alternative but try to find a satisfactory solution to their own problems (Simon, 1955). Economic behavior is influenced not only by rational calculation but also by institutions, i.e., habits, moral norms, and attitudes. From T. Veblen’s perspective, an individual’s behavior is determined by their habitual relations with members of their group, and these relations themselves, having an institutional character and force (the consistency of custom, prescription), change (Veblen, 1909). Habitual ways of acting and thinking not only become customary, simple, and obvious but are also sanctioned by social agreement, becoming correct and proper, generating principles of behavior (Veblen, 2024).

Thus, considering the provisions of these economic schools, it can be concluded that the grandmother institution has a dual nature. On the one hand, it is based on economic expediency, as it helps rationally distribute resources within the family. On the other hand, this institution represents an established tradition and a form of interaction between generations. Both economic schools note changes occurring in interfamilial relationships under the influence of various trends. In particular, the transformation of the grandmother institution in the 21st century is determined by the following main trends.

Demographic trends : a significant increase in life expectancy allows the older generation to interact more with the younger generation, while declining fertility naturally leads to a reduction in the number of grandchildren. This results in the development of new family models: with a predominance of the older generation over the younger (“top-heavy”) (Hagestad, 2006) or even a complete absence of younger generations. Such changes affect intergenerational relationships and the distribution of material resources (Arber, 2016). This also leads to the phenomenon of grandparental deprivation – discomfort from unrealized grandparental potential, delayed acquisition of the “grandmother/grandfather” status (Yanak, 2021).

Social trends: a shift in the value system of the population, including the elderly, toward self-realization and social interaction in society. According to sociologists, after the age of 60, there are more opportunities for an active life due to new technologies and forms of employment (Grigoryeva et al., 2023). However, the level of self-realization decreases after 60 years old due to deteriorating health and motivation changes (Kozlova, 2017). Furthermore, society has clear ideas about the behavior of older people. A study by Yu. Zelikova showed that contemporary Russian society is characterized by strict regulation of age and gender behavioral norms. For older women, the role of grandmother remains the only acceptable model of behavior (Zelikova, 2020).

Economic trends : growing labor shortages in the economy create a need to attract women and older people, previously engaged in child-rearing, to the labor market and promote the development of various childcare institutions. A sociological study by I.I. Korchagina showed that 60.2% of women in Moscow support the idea that “placing a child in a short-term group facilitates a woman’s return to employment after childbirth” (Korchagina, 2018). However, as noted in the work of R. Sarti, various childcare solutions (state services, paid nannies, care by grandparents or other relatives) are not mutually exclusive (Sarti, 2010). At the same time, opportunities for participation in grandchild care depend on the labor market demand for grandparents. However, in the labor market, they face a contradiction: on the one hand, there is significant demand for older workers (Zabelina, 2018), on the other hand, older people face discrimination (Vasilyeva, Tyrsin, 2021; Klepikova, Kolosnitsyna, 2017).

The literature actively studies individual aspects of the transformation of the role of older people, particularly grandmothers, in family and societal structures – demographic shifts, social norms, economic factors. However, this research attempts to form a systemic view of the transformation of the grandmother institution through an analysis of the demographic, social, and economic conditions influencing the behavior of all participants in these relationships.

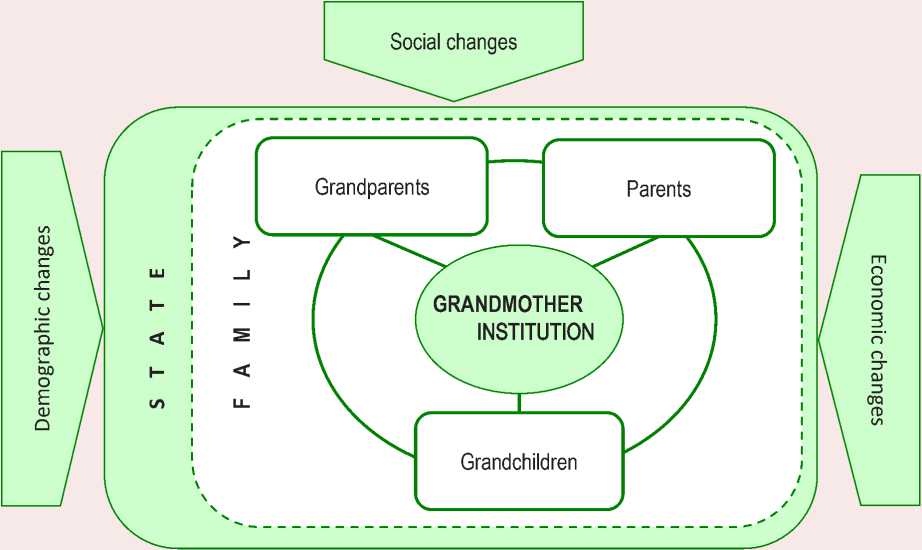

Figure 1. The grandmother institution

Source: own compilation.

Research approach

Under the influence of demographic, social, and economic changes, the grandmother institution is transforming, not only within the family environment but also in society ( Fig. 1 ). As noted by E.V. Konovalova, the family, influencing various relations in society, affects the nature of all processes in economic life (Konovalova, 2013). Therefore, to study the transformation of the grandmother institution, all participants in such relations are considered: grandparents themselves, parents, grandchildren, and the state as a participant shaping the environment in which this institution functions.

To analyze the transformation of the grandmother institution under the influence of modern realities, indicators describing the demographic and socio-economic conditions shaping the behavior of participants in these relationships have been defined.

Grandparents.

Number and potential of grandparents. Practically, grandparents include people who are the parents of the current generation’s parents; in other words, the family connection “grandmother/grand- father – grandchild” should exist. As O.M. Shubat states, official Russian statistics lack data allowing for such identification (Shubat, 2022). Based on indirect data (average age of women at childbirth) and estimates, she calculated that women, on average, become grandmothers when they are 48–49 years old, and men become grandfathers at 53 years old3. In this research, the criterion for grandparents is age. Conventionally, the population aged 55 and older is classified as such, which corresponds to the specifics of statistical reporting. The study aims to identify general trends, not specific cases of the grandmother institution, so this assumption is justified. For analysis, it is important to consider different age groups of older people, as the perception of early and late grandparenthood differs (Bulygina, Komarova, 2019). To analyze the potential of active aging as a factor in the participation of the older population in social and family life, indicators of health status and education level are included in the system (Zaidi et al., 2013).

Labor and social activity of grandparents. When analyzing the labor activity of grandparents, not only their employment rate (including the availability of the old age pension) was considered but also the nature of their professional functions (as managers and highly qualified specialists). Studying the reasons for continuing labor activity helps understand their choice between self-realization in society and fulfilling their traditional role in the family. Analysis of the social activity of grandparents was based on indicators of their involvement in active leisure, attendance at entertainment and sports events, and daily childcare.

Parents.

Number and characteristics of parental behavior. Analysis of parental behavior is based on indicators of households with children, their structure, and level of urbanization. Indicators of mothers’ reproductive behavior were analyzed separately.

Employment of mothers. According to the Family Code of Russia, parents have equal rights and obligations regarding children. However, the problem of combining work and childcare is particularly relevant for women (Zhuravleva, Gavrilova, 2017; Karabchuk, Nagernyak, 2013). Nobel laureate C. Goldin notes that despite the “quiet revolution” that changed women’s role in society, little has changed in the family (Goldin, 2025). Therefore, when analyzing the need for help from grandparents, the employment of mothers, their marital status, and the age of their children are considered.

Grandchildren.

Number of grandchildren. Relying on the available statistical database, grandchildren are defined as children and adolescents, i.e., the population under 18, which carries a certain degree of convention. Moreover, the age of the grandchildren themselves significantly influences the nature of their relationship with grandparents (Bulygina, Komarova, 2019). Children of early and preschool age receive maximum benefits from personal communication with them and their physical presence, while in adolescence the connection becomes less close. Therefore, preschool and school-age children and adolescents are considered separately.

Infrastructure for the upbringing and development of children and adolescents. Developed social infrastructure for children and adolescents allows parents to allocate their resources (time and attention) more effectively4, which accordingly reduces the need for help from grandparents in childcare.

The state.

The results of state activities in education, family relations, and employment are reflected in the indicators listed above; therefore, the analysis was based on describing the situation and development priorities of society and focused on qualitative aspects of institutional transformations.

The information base of the study consists of data from the Russian Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat), including results from federal statistical observations on socio-demographic problems and the results of the all-Russian population censuses, as well as results from sociological surveys conducted by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM) and other researchers. The main source of empirical data is the comprehensive observation of living conditions of the population, conducted by Rosstat since 2011; therefore, the selected research period is 2011–2024.

Figure 2. Number of older adults, as of January 1, million people

□ aged 55 and over □ aged 65 and over □ aged 75 and over

Source: Rosstat data.

Research results

Based on the proposed system of indicators, an analysis of the economic demand for the grandmother institution and its transformation under the influence of contemporary realities in Russia was conducted, showing individual participants in these relationships.

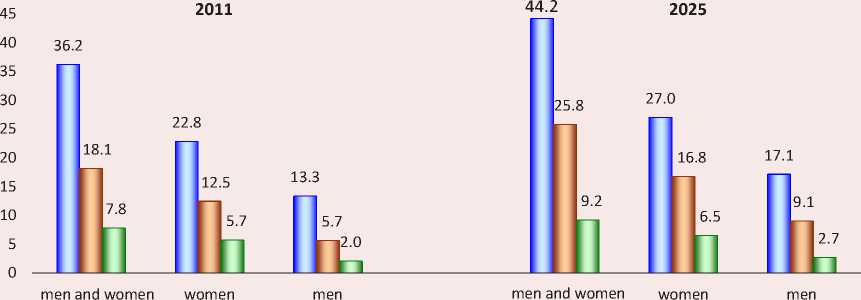

Grandparents . In Russia in 2011–2025, the number of older adults (aged 55 and over) increased significantly – from 36.2 to 44.2 million people, i.e., by 22% ( Fig. 2 ). Their share in the age structure of the population increased from 25.3 to 30.2%. However, the aging process is not “deep”: the share of the old-old people has not increased significantly, as there has been no substantial shift in mortality to older age groups (Vasilyeva, 2024). From 2011 to 2023, the remaining life expectancy for men aged 60 increased by only 2.6 years, and for women aged 55 increased by 2.2 years, reaching 17.7 and 27.0 years, respectively. The level of “feminization” of aging is decreasing: while in 2011 there were 171 women per 100 men aged 55 and over, in 2025 there were 158 women.

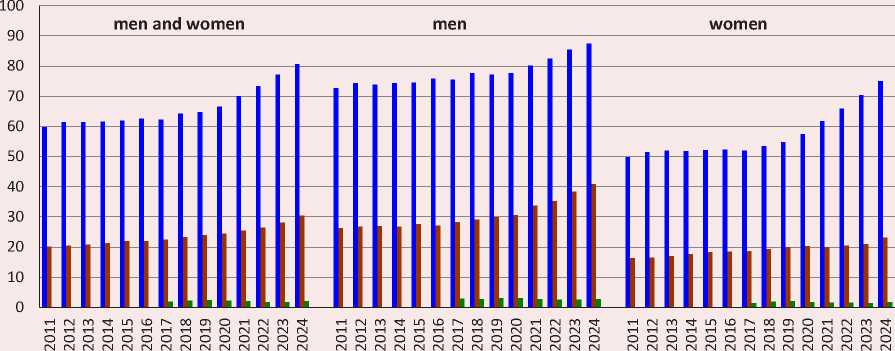

In 2011–2024, the employment rate of the older adults increased substantially (Fig. 3). The growth is primarily noted among women aged 55–59: from 2019 to 2024, their employment rate increased from 54.8 to 75.1%. Also, during this period, employment among men aged 60–69 rose from 29.9 to 40.9%. This dynamic in the labor activity of the older adults was influenced by changes in pension legislation, namely the increase in the retirement age. In 2012– 2023, the share of employed women aged 55 and over with higher education increased (from 28.8 to 32.3%), while among men the situation did not change significantly (from 25.7 to 25.4%).

Furthermore, from 2011 to 2023, the share of highly qualified specialists among women over 55 increased from 28.8 to 33.7%, with the most notable growth in the 55–59 age group – from 28.0 to 33.3% ( Fig. 4 ). Among older men, conversely, the share of highly qualified specialists is decreasing. From 2011 to 2023, the number of older managers decreased from 521.1 to 352.6 thousand people, and their share – from 12.4 to 9.0% of employed men aged 55 and over. At the same time, the share of managers aged 50 and over not only remains the highest among all age groups but also increased from 32.2% of all managers in 2012 to 36.3% in 2024.

Figure 3. Employment rate by age groups, %

■ aged 55-59 ■ aged 60-69* ■ aged 70 and over*

Note: * Before 2017 it was the 60–72 age group.

Source: Rosstat data. Results of the labor force sample survey.

Figure 4. Share of managers and highly qualified specialists, % of the employed of respective gender and age

Source: Rosstat data.

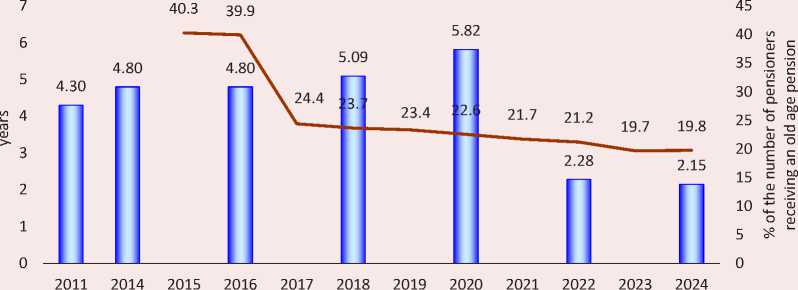

The dynamics of labor activity among the older adults and labor activity among pensioners receiving old age pensions are opposite. As seen in Figure 5, employment among pensioners, on the contrary, is declining. First, the introduction of the federal law on “non-indexation of pensions for working pensioners” in 2017 alone reduced their share from 39.9 to 24.4%. Second, the increase in the retirement age reduced the average post-retirement length of employment of pensioners from 5.8 years in 2020 to 2.3 years in 2022. Moreover, these trends persist; according to 2024 data, the share of working pensioners was 19.8%, and the average length of employment after being granted an old age

Figure 5. Labor activity of pensioners

■ ■ The average length of employment after the appointment of an old age pension*

^^^^^^^^м The share of working pensioners receiving an old age pension

Note: * In the year of reaching the generally established retirement age.

Source: Rosstat data. Comprehensive observation of living conditions of the population.

pension was 2.2 years. According to a 2020 VCIOM survey5, Russians believe the reasons pensioners continue working are insufficient pensions (74%), the desire to provide financial support to children and grandchildren (56%), the wish to be with people, in a community (32%), as well as interest in the work (19%) or the habit of working (16%). Similar results were shown by a 2020 survey of working pensioners in Saratov (Shakhmatova, 2021): insufficient pensions (81%), desire to provide financial support to children, grandchildren (36%), wish to avoid loneliness, be among people, in a community (28%), habit of working (24%), interest in work, desire to work (21%), with no gender differences found in responses. Data from a survey of the population in the Vologda Region (Ilyin et al., 2025) confirm that instrumental motives of the need for additional earnings (41%) and the desire to be financially independent, including to support children and grandchildren (40%), predominate among the motives for continuing work.

In 2011–2024, there were changes in the nature of social activity among the older population. The share of older adults capable of leading an active lifestyle and engaged in any form of active recreation varies between 5–8%, among women it is slightly lower (4–6%). Of those capable of an active life, in 2024 only one fourth engaged in any form of active recreation (one third in 2011). This generally confirms the conclusion drawn from a 2021 survey of residents of the Sverdlovsk Region (Neshataev, 2022): grandparents are more inclined toward passive leisure and “domesticated” activities, with the most popular forms of leisure among the surveyed grandparents being help in raising grandchildren (48.6%) and work at a dacha or vegetable garden (47.8%). At the same time, the structure of regularly attended events changed: the increase is recorded in the share of the older adults going to the cinema (from 1.2 to 12.6%), theater (from 2.8 to 15.0%), concerts (from 3.9 to 17.3%), art exhibitions, museums (from 1.9 to 9.5%), restaurants, cafes, bars (from 1.8 to 28.7%), sports events (from 2.4 to 7.0%), but religious institutions are still at the top (from 22.5 to 33.1%). The share of older adults who went on a tourist or excursion trip in the past 12 months increased significantly (from 7.8 to 42.3%).

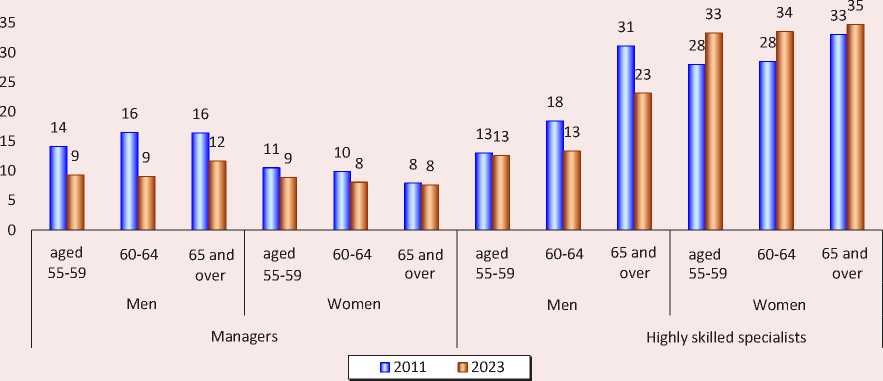

As shown by the results of statistical observations, there are no such processes as a reduction in the significance of the traditional the grandmother institution (Arutyunyan, 2012) or the disappearance of the “Russian grandmother” phenomenon (Sorokin, 2014). In 2011–2024, the share of people aged 55 and over providing daily childcare increased from 19.1 to 28.8% (Fig. 6). This growth is noted both among grandmothers (from 22.2 to 32.2%) and among grandfathers (from 13.2 to 23.4%). A.V. Korolenko found that women aged 60–64 with a high level of education, continuing to work while receiving a pension, and not living alone, communicate more with younger generations (Korolenko, 2018). Yu. Zelikova believes that established social norms and rules, postulating that there is only one role for older women – grandmother – lead to their self-discrimination (Zelikova, 2020). This corresponds to the results of a 2024 VCIOM survey6: 69–75% of older Russians believe that maximum participation of grandparents in raising grandchildren is necessary, whereas only 12–18% support the idea of “free” grandparents. Notably, the younger generations (Generation Z and Millennials) demonstrate a different position: the older adults should live primarily for themselves (48–55%), not for their grandchildren (28–36%).

Parents . According to the results of the 2010 and 2020 all-Russian population censuses, the number of households with children under 18 decreased by 2.6 million ( Table ), while there is an increasing number of single mothers (from 2.1 to 2.7 million) and fathers (from 226 to 494 thousand). The share of households consisting of single parents with children increased from 13.0% to 21.1% of the number of households with children. It is necessary to note that during the period under review, the number of divorces decreased (from 2011–2024 – from 4.7 to 4.4 divorces per 1,000 people), but the number of marriages also significantly decreased (from 9.2 to 6.0 per 1,000 people).

Figure 6. The share of people aged 55 and over providing daily care for children (their own or others’), %

□ men and women □ men □ women

Source: Rosstat data. Comprehensive observation of living conditions of the population.

Table. Number of households with children under the age of 18, thousand households

|

Households |

2010 |

2020 |

|

Households with children under 18 |

17877 |

15231 |

|

Households consisting of a mother with children under 18 |

2095 |

2727 |

|

Households consisting of a father with children under 18 |

226 |

494 |

|

Households consisting of a mother (father) with children under 18 and one of the parents of the mother (father) |

894 |

805 |

|

Source: Rosstat data; all-Russian population censuses 2010 and 2020 |

||

Though the number of households consisting of one parent with children and a grandmother (or grandfather) decreased from 894 to 805 thousand, their share persists (in 2010 – 5.0%, in 2020 – 5.3% of households with children). T.L. Kuzmishina notes that living with grandparents creates a distortion of family system boundaries (Kuzmishina, 2014). This can lead to tension in relations between mothers and grandmothers when their ideas about child-rearing do not coincide (Bektas et al., 2022; Con Wright, 2025), so parents need their own parents’ help in raising children but limit it. J. Mason, V. May, and L. Clarke formulated this consensus as “being on hand” and “not interfering” (Mason et al., 2007). According to a 2005 survey, 51% of respondents favored limited participation of grandparents in raising grandchildren (Vovk, 2006). A 2020 VCIOM study7 showed that only 27% of Russians are inclined to entrust upbringing to a grandmother or grandfather. The majority (66%) believe that it is better for a young family without financial difficulties to send their children to kindergarten, with women and the 35–44 age group stating this more often (69 and 74%, respectively). According to the sociological study “Family and Family Generations: A Generational View” (Rostovskaya, Egorychev, 2022), 65.1% of parents care for children themselves, and only 3.4% of respondents answered that grandparents take on this role. T.K. Rostovskaya and A.M. Egorychev associate this with the influence of the Soviet legacy on the family institution. In the Russian family, gender norms of the Soviet era persist, according to which a woman can work and build a career, but the primary responsibility for the family and children lies with her (Dobrokheb, Ballaeva, 2018). At the same time, the Western ideology of intensive motherhood is gaining popularity in Russia (Isupova, 2018), although this parenting standard is not perceived equally by all parents (Faircloth, 2023).

Another parameter of households is their level of urbanization: 73.5% of households with children live in urban settlements, and 26.5% in rural areas; this ratio did not change during the analyzed period.

E.V. Zemlyanova and V.Zh. Chumarina showed a change in the age model of fertility in Russia, with a shift toward older ages (Zemlyanova, Chumarina, 2018). From 2011 to 2022, the average age of mothers at childbirth increased from 27.7 to 28.9 years. As a result, grandparents remain in a long wait for grandchildren, and when grandchildren appear, they themselves often need help from relatives (Gurko, 2020).

As rightly noted in the National Strategy for Women for 2023–20308, women in Russia are oriented toward full employment, career growth combined with family responsibilities and childrearing. In 2011–2024, the share of employed women with preschool-age children increased from 63.6 to 67.6% ( Fig. 7 ). However, since the “pandemic year”, the employment rate of women with children under three has been

Figure 7. Employment rate in women aged 20–49, %

90.0

85.0

80.0

75.0

70.0

65.0

60.0

55.0

50.0

45.0

81.4 82.0 82.8

78.8 79.4 78.3 80.2

76.0

88.7

76.0

76.4 76.6 76.0 76.8 77.9

77.8 78.6 79.2 78.7 77.5 79.4 80.2

with children under 18 with children aged 0-2

with children aged 0-6

without children under 18

Source: Rosstat data. Results of the labor force sample survey.

decreasing; in 2019 it was 50.9%, and in 2024 it was 45.8%. Overall, women’s employment does not depend on whether they have children; since 2019, the employment rate among women with children has even been higher than among women without children (in 2024 – 82.8 and 81.4%, respectively).

The employment of married and single mothers is increasing, but the employment of unmarried women is higher. Among single mothers whose youngest child is under 15, 76.7% had full-time employment (in 2021 – 74.1%), 16.7% were unemployed (in 2021 – 18.5%). Among married mothers, 69.0% had full-time employment (in 2021 – 64.2%) and 22.1% were unemployed (in 2021 – 24.5%).

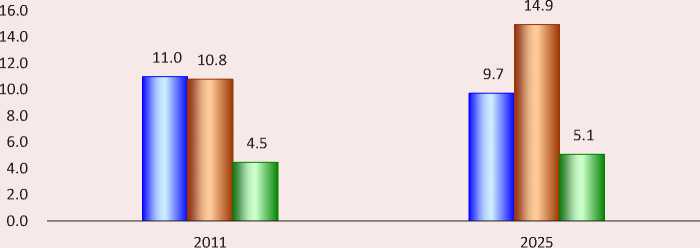

Grandchildren. In Russia, the ratio of the older generation’s size to the young generation’s size is increasing. Conventionally, in 2011 there were 2.8 persons aged over 55 per one grandchild (persons under 18), in 2025 – 3.1. In 2011–2025, the number of children (aged 14 and under) increased from 21.8 to 24.7 million people (Fig. 8). However, the number of preschool-age children is declining, which is associated with the preserved wave-like deformation of the age composition of Russia’s population9, and considering the negative dynamics of fertility, a further reduction in the size of this age group and the number of children in general is expected. According to a Rosstat forecast10, in 2024–2042, there will be a 1.2-fold decrease in the population younger than working age (15 and under). The number of adolescents (15–17 years) from 2011 to 2025 increased by 603.6 thousand people; in 2025 it amounted to 5.1 million people. Such an age structure of children and adolescents in Russia undoubtedly influences the grandmother institution and the prospects for its development.

In 2011–2024, the accessibility of services related to the education and upbringing of children improved. While in 2011 there were 570 places per 1,000 children for preschool-age children in

Figure 8. Population aged 17 and under, as of January 1, million people

□ aged 0-6 □ aged 7-14 □ aged 15-17

Source: Rosstat data.

preschool educational institutions, in 2024 there were 811 places. At the same time, according to HSE statistical yearbooks11, in 2011–2023 the number of preschool education institutions decreased from 45 to 32 thousand. The increase in accessibility, as noted by A.L. Sinitsa, is associated with the consolidation of groups and the development of short-term groups for children (Sinitsa, 2017). This assumption is indirectly confirmed by the growth in the number of childcare workers (in 2010–2023 from 485.2 to 509.4 thousand) and their workload (from 11 to 13 children per 1 worker). The HSE analytical report “Vectors of Preschool Education Development in the Context of Modern Challenges” states that the government supports the creation of new places for children under three in the non-public sector of preschool education, including based on public-private partnerships (Abankina et al., 2022). In particular, the national project “Demography” provides for subsidies from the federal budget to individual entrepreneurs and non-public organizations for creating additional groups for children aged one and a half to three years in private kindergartens. However, the proportion of children attending private preschool education institutions remains stable and does not exceed 1.5% of the total number of children in preschool education institutions. This may indicate the high accessibility of state education and the relatively low demand for private education.

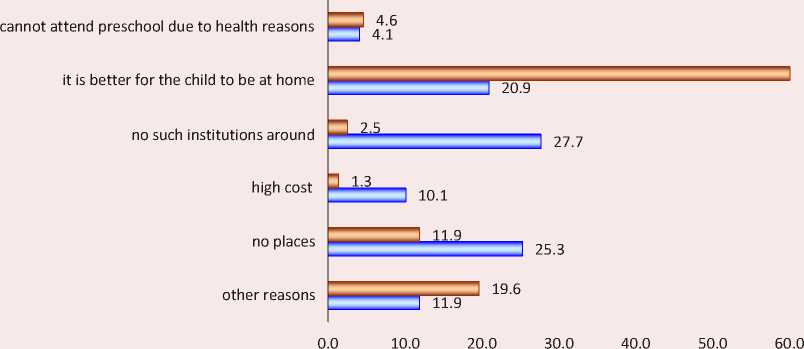

In 2011–2024, the share of children aged 3–6 who were placed on a waiting list for a place in a preschool education institution increased from 25.9 to 37.7% of the total number of children of the corresponding age not attending a preschool education institution. During this period, the structure of reasons for children not attending kindergarten changed significantly. In 2011–2024, the physical and financial accessibility of preschool institutions increased; the share of children not attending a preschool education institution due to high cost and lack of places decreased from 63.1 to 15.7% ( Fig. 9 ). In 2024, 60% of children aged 3–6 did not attend preschool institutions because “it is better for the child to be at home” (in 2011 – only 20.9%).

In 2011–2024, the share of children aged 5–17 enrolled in supplementary education programs increased significantly relative to the total number of children in this age category (from 39.3 to 85.9%). During the period under review, the

Figure 9. Distribution of children aged 3–6 by reasons for not attending preschool education institution, % of total number of children of corresponding age not attending preschool education institution

о 2024 □ 2011

Source: Rosstat data. Comprehensive observation of living conditions of the population.

number of children who vacationed in children’s and adolescents’ summer recreational institutions did not change; in 2024 it was 5.8 million people. At the same time, the number of children’s and adolescents’ summer recreational institutions significantly decreased (from 52 to 38.9 thousand).

The state. According to Russian legislation, parents are responsible for their children. Article 38 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation states that care for children and their upbringing are the equal right and obligation of parents. The Family Code of the Russian Federation (Article 67) grants grandparents and other relatives only the right to communicate with the child but does not impose any obligations for their upbringing or support. The Labor Code of the Russian Federation (Article 256) grants relatives the right to take parental leave to care for a child, provided the parents are not using it and not receiving corresponding payments. This delineation of rights and obligations is essential in determining the circle of persons responsible for the well-being of minors. The literature contains attempts to consider the grandmother institution – the care of grandparents for their grandchildren – through the lens of labor relations, defining it as “grandparental labor” requiring payment (Bagirova, Sapozhnikova, 2021). D.G. Saitova proposed a mechanism for state stimulation of such labor, where the state acts as the “employer”, not the parents, whose duty it is to care for and raise their children (Saitova, 2022). Stimulating “grandparental labor” from a legal standpoint is not only unjustified but also economically inexpedient. In fact, it means transitioning an officially employed worker, possessing significant and unique professional skills by the end of their working life and being a taxpayer, into an “unprofessional” worker on the informal labor market, who in rare cases possesses the necessary competencies in child-rearing.

In the context of a declining working-age population and growing personnel shortages in Russia, the state is implementing a comprehensive policy to support the employment, paying special attention to women and people of pre-retirement and retirement ages as a significant part of the Russia’s labor potential. This policy aims to develop an effective employment system that considers the needs of all categories of citizens striving for professional realization while maintaining family obligations. The state shares responsibility with parents for raising children, creating conditions for the early development of children under three and for the labor activity of women with children12. In 2021, the federal project “Employment Promotion” was launched within the national project “Demography”; from 2025 it has been transformed and incorporated into the national project “Personnel”. An important component of this project is expanding opportunities for young mothers to return to the labor market after parental leave, providing them with educational pathways (Abankina et al., 2022). The state also encourages businesses actively implementing programs to support working women with children and promote women’s careers13. Furthermore, to ensure quality care and development of the child, the professional standard “Nanny (Worker for Supervising and Caring for Children)” was approved in 2018, which systematizes requirements for specialists.

In 2016, the Strategy for Action in the Interests of Senior Citizens up to 203014 was approved, which provides for the active involvement of older people in economic activity. In this strategy, measures in the area of the older adults employment are proposed, such as supporting entrepreneurial initiatives of senior citizens, developing forms of employment (domestic, temporary, flexible, and remote), creating conditions to prevent discrimination against older people in the labor market and to continue their labor activity after reaching retirement age, developing mentorship programs, as well as training and retraining older people, including pre-retirees.

Russian state policy pays special attention to strengthening intergenerational ties as a crucial element of developing the family institution. In particular, one of the tasks of the Strategy for the Comprehensive Safety of Children for the Period up to 203015 is to create conditions for intergenerational interaction and ensuring generational continuity. The Concept of State Family Policy of Russia for the period up to 202516 is also aimed, among other things, at strengthening intergenerational ties.

Discussion of results

The analysis revealed two interrelated trends in modern Russian society: a significant increase in the labor activity of older people, primarily among women, and, concurrently, an intensification of their participation in raising the younger generation. The trend of more active participation of grandparents in the lives of their grandchildren is characteristic not only of Russia. According to data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), 44% of grandparents in 11 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland) provide childcare without the presence of the parents (Glaser et al., 2013). In the UK, data from the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey show that 63% of grandparents are involved in raising grandchildren (Wellard, 2011).

According to a study by Dutch researchers, the probability of grandparents caring for their adult daughters’ children increased from 0.23 to 0.41 in 1992–2006 (Geurts et al., 2014). Moreover, the same study claims that if the employment level of the older population had not increased, the growth of this indicator would have been more significant. Analysis of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) – a survey of a representative sample of Americans over 50 – indicates that grandchild care by grandparents is becoming increasingly common, especially among families with low socioeconomic status (Lee, Tang, 2015). Researchers from King’s College London (di Gessa et al., 2016), using SHARE data, explain the higher level of intensive grandchild care by grandparents with the unavailability of formal childcare and the full-time employment of mothers. This relationship is clearly traced using the example of 11 European countries. In countries such as Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Spain, where mothers work overtime, more than 40 hours per week, and there are practically no specialized childcare institutions, a high degree of grandparental participation is noted. In the UK, Netherlands, and Germany, few mothers are engaged in prolonged labor, consequently they rely much less on grandmothers for intensive childcare (Glaser et al., 2013). M.H. Meyer, based on interviews with working American grandmothers, concluded that many of them change their work schedules, use vacation and sick leave time, and reduce retirement savings partly because they have more social security, flexibility, and resources than their daughters (Meyer, 2012).

If European and American studies demonstrate a predominantly economic basis for the motivation of grandmothers in caring for grandchildren, the results of Russian sociological studies show its institutional character. A survey of older Ossetian women with grandchildren indicates that 89% of them consider helping their grandchildren an obligation, and 60% of respondents would feel guilty if they did not provide such support (Dzagurova, 2021). A.V. Kuramshev, E.E. Kutyavina, and S.A. Sud’in note that the grandmothers’ own needs and interests are given a low priority, and the entire daily schedule is built around the grandchildren. A study based on a survey of grandmothers revealed that sacrificial attitudes are characteristic of the majority of respondents (Kuramshev et al., 2017).

Studying the behavioral models of grandparents in Russia and Western European countries demonstrates the limitations of existing economic theories in explaining their motivation for participating in grandchild care. Many studies show that, despite natural changes in the character of “grandparent-grandchild” communication, the intergenerational ties remain an important component of the family system (Kemp, 2007), driven by both practical and emotional aspects. At the same time, according to the results of sociological studies, the Russian specificity is manifested in the absence of a dominant rational logic in the redistribution of resources within the family. This is traced when comparing behavioral patterns of the population in Russia and Estonia based on SHARE data (Sinyavskaya et al., 2023). If in Estonia, the chances of helping grandchildren are higher for working elderly and those assessing their income more highly, in Russia no statistically significant connection was found between involvement in helping grandchildren and social status or subjective income.

Conclusion

This research attempted to analyze the trends and socio-economic conditions of the transformation of the grandmother institution in Russia, based not on assumptions about the realization of ideas of active aging, self-realization, narcissism, feminism in the public consciousness, but on the results of statistical observations in the recent past. The scientific novelty of the study lies in developing a systemic approach to studying the grandmother institution, based on the analysis of demographic, social, and economic factors influencing the development of behavioral patterns of all participants in these relationships: grandparents, parents, grandchildren, and the state. The results show that the older population of Russia demonstrates a trend toward greater social and labor activity while preserving traditional forms of participation in family life, including raising grandchildren. Since the grandmother institution is not a unique phenomenon characteristic exclusively of Russian society, European studies were also considered. Comparing the findings, we can conclude that there are differences in the motivation of grandparents that do not fit into the framework of one economic theory: neoclassical theory and neo-institutional theory. In Russia, grandmothers perceive caring for their grandchildren as a right, traditional form of interfamilial interaction. In Europe, grandmothers explain their help by economic expediency. Although this conclusion requires more detailed research with more comparable initial data, it can be unequivocally stated that the grandmother institution is not a social rudiment.

The study showed that the grandmother institution is not disappearing but is transforming, adapting to new socio-economic conditions, while retaining its significance both for the family and for society as a whole. M.Yu. Arutyunyan formulated the vector of this transformation as moving from a “substitutive” or even supplementary function relative to the parental one, toward an independent role (Arutyunyan, 2012). Indeed, there is a substantial increase in the employment of the older population, especially among women aged 55–59. Not only is there an increase in the education level of working older women, but also in the share of highly qualified specialists among them, and the leading position of older persons among managers persists. While the labor activity of the older population is growing, the labor activity of pensioners is declining. This divergent dynamic shows that a significant portion of preretirement and retirement age citizens demonstrate a desire to continue working, postponing pension registration. This indicates the preservation of high labor motivation among the older generation and their intention to remain economically active participants in the labor market. Moreover, according to surveys, a significant motive is also the desire to help children and grandchildren. At the same time, the social activity of the older adults is increasing, the spectrum of leisure activities is expanding, and participation in the cultural life of society is growing. Despite the decrease in the number of preschool-age children, a steady increase in the participation of older people in caring for grandchildren is recorded. This growth can be explained by the increase in the number and share of single-parent households with children, as well as the increase in labor activity among women with children. The significant personnel deficit in the Russian labor market prompts the state to conduct a comprehensive policy aimed at stimulating employment, especially among women and the older adults as a significant part of the Russia’s labor potential. At the same time, the state seeks to maintain a balance between engaging these groups in labor activity and strengthening intergenerational ties through the implementation of family policy measures.

Such a transformation of the grandmother institution requires creating conditions that allow the older generation to harmoniously combine labor activity with participation in raising grandchildren.

Key directions here could be the introduction of flexible forms of employment, the development of infrastructure for children, and the integration of family policy and active aging programs. Improvements in these areas will contribute not only to satisfying the interests of older people in professional and family aspects but also to reducing demographic risks (e.g., refusal to have a second or third child due to lack of support). This approach does not contradict traditional values but relies on them, turning the grandmother institution into a resource for the sustainable development of Russian society.