Экология горного барана (Ovis ammon) в заказнике “Их Нарт”, Монголия

Автор: Амгаланбаатар Сух, Ридинг Ричард Р., Доржиев Цыдыпжап Заятуевич

Журнал: Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Философия @vestnik-bsu

Рубрика: Зоология

Статья в выпуске: 4, 2012 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Приведены результаты исследований по экологии горного барана (аргали) в заказнике “Их нарт” в Монголии и обоснована необходимость продолжения непрерывного слежения за состоянием его популяции.

Горный баран (ovis ammon), заказник "их нарт", экология, мониторинг

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148180998

IDR: 148180998 | УДК: 599.73(517.3)

Текст научной статьи Экология горного барана (Ovis ammon) в заказнике “Их Нарт”, Монголия

Study Area

We conducted our field in “Ikh nart” Nature Reserve, located in northwestern Dornogobi Aimag, Mongolia. Ikh Nart was established in 1996 to protect 66,760 ha of rocky outcrops and its wildlife on the northern edge of the Gobi [4]. The region is a high upland (-1,200 m) covered by semi-arid steppe vegetation.

Methods

We used drive nets, hand captures of neonatal lambs, and darting to capture animals for radio telemetry. We only briefly describe each method here; for more detail see [5, 6]. We darted argali using Pneu-Dart® rifles with telescopic or red dot scopes and .50 caliber type C Pneu-Dart darts with barbed needles.

All radio collars were equipped with mortality switches.

We tracked collared argali throughout the year using a traditional receiver, antenna, and global positioning system (GPS) and binoculars or spotting scopes to sight animals at a distance and thus avoid influencing movements. Followed the guidelines proposed by Thompson et al. (1998) for distance sampling on line transect surveys.

We collected data on vegetation consumed, fecal composition, and plant digestibility and nutritional content for argali and domestic sheep and goats (hereafter shoats) to assess the degree of dietary overlap and selection forage [7].

We examined plant availability during each season by establishing 100 random Daubenmire plots (1 m x 1 m) [2] within the study area.

We incorporated telemetry data into a geographic information system (GIS) for analyses.

We used the Spatial Analyst and Animal Movement extensions for ArcView 3.2® to determine 100% minimum convex polygon (MCP) and adaptive kernel (hereafter kernel) home ranges for all animals with >15 independent locations (i.e., 1 location/day) over 90 or more days.

Home Range & Movement Patterns .

From 2000-2005, we captured and radio collared 74 argali in Ikh Nart.

Of these, 68.9% (n = 51) were lambs and 58.1% (n = 43) were hand captures of neonatal lambs. From November 2000 to December 2005, we collected radio telemetry locations on argali sheep in Ikh Nart and the surrounding area. We recently analyzed and published data through May, 2004 (some 1,042 telemetry locations) [5, 6].

Yearly home range sizes neared an asymptote after we recorded greater than about 35 fixes on different days for 100% MCP, 95% kernel, and, to a lesser extent, 75% kernel home ranges for argali in Ikh Nart.

The 50% kernel home ranges remained almost constant beginning with just 15 fixes. As such, for most analyses we used only animals for which we had >35 fixes each year.

Although we collared our first argali in late 2000, we did not refine our capture techniques until late 2002 (drive nets) and early 2003 (lamb captures). As such, most our data comes from animals monitored subsequent to 2002 and primarily 2004-2005. In 2004 we monitored 27 argali for an average of 196.9 ±20.1 days, collecting telemetry data on an average of 30.7 ±3.0 days (Table 1).

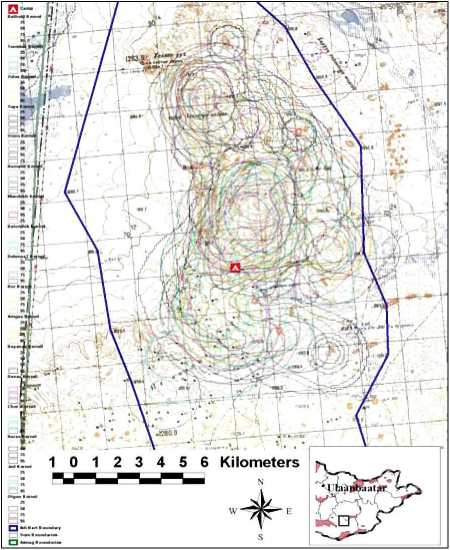

Figure 1. Kernel Home Ranges (95%, 75% 50% and 25%) for 17 Radio Collared Argali (Oils ammori) in Ikh Nartiin Chuluu Nature Reserve, Mongolia, 2000-2004. Data based on 1 location/day only.

Table 1. Home range sizes (km2) of argali sheep (Ovis ammon) in Ikh Nartiin Chuluu Nature Reserve, Mongolia, 2001-2004. Study days refer to the number of the days from animal capture until death or last telemetry location. Telemetry days refer to the number of days for which we received at least one location on an animal.

Study Telemetry 100% Minimum Kernel Home Ranges

Animals with >375 study days and >45 telemetry days

|

Mean S.E. |

459.43 73.29 69.49 75.59 26.53 7.80 3.75 37.88 36.22 2.93 5.08 2.97 2.97 0.79 |

Of these animals, we gathered data on >35 days for 9 argali (mean = 54.8 ±4.7 days), of which 3 were ewes, 4 were lambs, and 2 were rams. In 2005 we monitored 21 argali over 285.3 ±25.6 days and were able to obtain day on 42.6 ±4.7 days. Eleven of these animals (8 ewes, 1 lamb, and 2 rams) were tracked for >35 days (mean = 59.4 ±4.7 days).

Argali in Ikh Nart, at least those collared in our study to date, do not engage in seasonal migrations [6].

Diet & Dietary Overlap .

Results of our research into argali diet and dietary overlap with livestock in detail. We only provide a summary of that work here. Available forage biomass decreased significantly in Ikh Nart from summer to winter, from 19g/m2 to 3.4g/m2. Even during summer, our results show low productivity, especially compared with other regions of the Gobi [1,3].

Fecal analysis determined the plants that argali and shoats consumed during different seasons of the year more accurately than direct observations [7]. Argali consumed a more varied diet than shoats in all seasons, with 12 key species comprising 58.0% of their diet in summer, followed by 46.9% in fall, 68.6% in winter, and 66.4% in spring. In comparison, shoats relied on only 9 key plant species to comprise 70.0% of their summer diet and 63.6%, 75.3%, and 78.0% of their diet in autumn, winter, and spring, respectively.

Argali and shoats preferred different species of plants at different times of the year. For a list of all species consumed by argali and shoats [7].

We found high dietary overlap between argali and shoats no matter the season, category of plant, or index used [7]. Dietary overlap ranged as high as 92% in summer and 99% in winter. Dietary overlap was greater in winter and spring (85% - 99%), when food resources are more limiting, than in summer and autumn (72% - 94%). The high degree of dietary overlap, low biomass availability, and extremely cold winters in Ikh Nart suggests that a strong potential for competition exists between argali and shoats it. As a result, reduction of livestock grazing in the reserve would likely improve the situation for argali.

Argali Population Size.

We began conducting population surveys in

September 2004 using distance sampling. Unfortunately, none of our surveys yielded sufficient data (recommend minimum = 40 groups; Buckland et al. 1993, Laake et al. 1993) for accurate modeling, although we came close to this total on April 9, 2005. Our small sample sizes yielded huge 95% confidence limits for density estimates that ranged range from 1.32 - 11.40 animals/km2 in September 2004 to 4.49 - 63.55 animals/km2 in April 2005 (or 212 - 1,824 argali to 718 - 10,168 argali for the 160 km2 we surveyed, respectively). Even our point estimates varied widely from 3.87 -16.90 argali/km2 (619 - 2,704 total argali). We are unable to discern trends given the poor precision of these estimates.

Mortality .

Of the 74 argali we collared in Ikh Nart since 2000, 49 (66.2%) have died. The vast majority (73.5%) of argali mortalities occurred in spring, with relatively equivalent mortality rates during other seasons. Yet, lambs comprised the vast majority (75.5) of the mortalities we recorded, and we would expect high mortality rates for neonatal animals, which comprised 59.2% of all mortalities. However, adults and yearlings still suffered 58.3% of their mortalities in spring. To our surprise, winter mortality has remained relatively low (8.3-10.8%) to date.

Predators killed the majority of argali (n = 19) for which we could determine a cause of death. In addition, 3 died from disease, 4 neonatal lambs died of maternal neglect during a particularly dry spring, 1 died of starvation during a harsh winter, and 1 died from an attack by a domestic horse that it startled. We could not determine the cause of death for the other 16 animals.

Predation appears to result in most argali deaths at our research site, but for 11 (57.9%) argali killed by predators, we were unable to determine the predator.