Keats’s sonnet on Chapman’s translation of Homer: early draft of manuscript and initial publication

Бесплатный доступ

This work represents a comparative study of the earliest known manuscript of John Keats’s sonnet devoted to the translation of Homer’s “Iliad” performed by George Chapman in 1611, with the first publication of the sonnet in 1816.

Keats, chapman, iliad, indo-european

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148160611

IDR: 148160611 | УДК: 82.1

Текст научной статьи Keats’s sonnet on Chapman’s translation of Homer: early draft of manuscript and initial publication

ВЕСТНИК 2016

The1purpose2of the article is to present a copy of a manuscript of Keats’s sonnet on Chapman’s translation of Homer, in comparison with the text of the initial publication of this sonnet, along with related philological and literary comments.

Keats’s sonnet on Chapman’s translation of the Iliad is well known, having frequently been included in collections of Keats’s works. Later authors with references to Keats’s sonnet to Chapman include Poe, Nabokov and P.G. Woodehouse.

Following partial translations from the Iliad in 1598 and 1608, Chapman released the complete twenty-four books under the title The Iliads of Homer in 16113.

Prior to composing the sonnet (1816) on Chapman’s work, Keats had completed a translation of The Aeneid , in 1811.

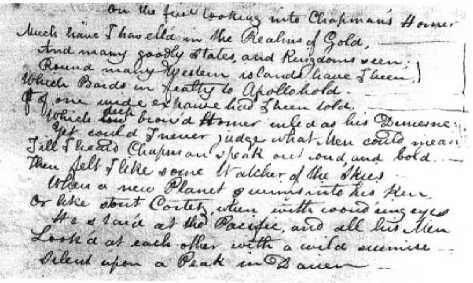

For purposes of reference, the manuscript reproduced below is identified as Keats, John, 1795– 1821. Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold. A. MS., early draft, MS Keats 2.4, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MASS.

The following is a reading of the manuscript (Ms.), presented beside the text of the first publication of the same sonnet, for purposes of comparison.

On the first looking into Chapman’s Homer Much have I travell’d in the Realms of Gold, And many goodly States and Kingdoms seen; Round many Western islands have I been, Which Bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told, Which deep brow’d Homer ruled as his Demesne: Yet could I never judge what Men could mean, Till I heard Chapman speak out loud, and bold. Then felt I like some Watcher of the Skies When a new Planet swims into his Ken, Or like stout Cortez, when with wond’ring eyes He star’d at the Pacific, and all his Men Look’d at each other with a wild surmise Silent upon a Peak in Darien.

Features1of capitalization, punctuation and vocabulary in the Ms. and The Examiner .

Title: Ms.: On the first..., Examiner : On first... (without “the”).

-

l.1. Ms.: Realms of Gold..., Examiner : realms of gold... (without capitalization).

-

l.2. Ms.: States and Kingdoms..., Examiner : States and Kingdoms... (later publ. w/o caps).

-

l.3. Ms.: Western..., Examiner : western... (without capitalization).

-

l.4. Ms.: Bards..., Examiner : Bards... (without capitalization in later publications).

-

l.5. Ms.: Oft..., Examiner But... (different wording).

-

l.6. Ms.: Demesne:, Examiner : demesne; (semicolon instead of colon).

-

l.7. Ms.: Men, Examiner : men (without capitalization).

-

l.8. Ms.: loud, ... bold. Examiner : loud (no comma)... bold: (end w/colon, not period).

-

l.9. Ms.: Watcher of the Skies, Examiner : watcher of the skies.

-

l.10. Ms.: Planet... Ken, Examiner : planet... ken; (without capitalization).

-

l.11. Ms.: wond’ring eyes, Examiner : eagle eyes. (different wording).

-

l.12. Ms.: Pacific, ... Men, Examiner : Pacific, – ...men (dash after Pacific ).

-

l.13. Ms.: surmise, Examiner : surmise, – (comma and dash after ‘surmise’).

-

l.14. Ms.: Peak..., Oxford: peak (without capitalization).

The following philological comments are made for the purpose of clarifying some of the words in

On first looking into Chapman’s Homer1 Much have I travell’d in the realms of Gold, And many goodly States and Kingdoms seen; Round many western islands have I been Which Bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

But of one wide expanse had I been told, Which deep brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne; Yet could I never judge what men could mean, Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold: Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez, when with eagle eyes He star’d at the Pacifiс – and all his men Look’d at each other with a wild surmise, – Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

the sonnet, as well as indicating the nature of Keats’s vocabulary.

Line 1: realm, Middle English roialme , realme , Old French realme , French royaume “kingdom”, from late Latin * regalimen , accusative of regalis “royal”, from Indo-European * reg - “to move in a straight line” with derivatives meaning “to direct in a straight line”, oldest form * hreg -. Lengthened-grade form * reg - was Indo-European word for a tribal king, source of Old High German -rTh “king, ruler”, used as a suffix in personal names. Suffixed form * reg - en - was source of Sanskrit raja , rajan -“king, rajah”, feminine rajni “queen, rani” and rajati “he rules”.

Line 2: goodly is the combination of good plus the suffix -ly , meaning “somewhat large, considerable”, with good via Old English god , from Germanic * godaz , “fitting, suitable”, allied to Old Slavonic godǔ “fit season” and Russian годный “fit, suitable”, from common origin in earlier Indo-European * ghedh - “to unite, join, fit”, while kingdom “country, state ruled by a king” is from Old English cyningdom : king + dom , hence literally the “domain of a king”; state comes via Old French estat from Latin statum , accusative of status “standing, condition”, supine of stare “to stand”, earlier IndoEuropean “stood”, * sta- “to stand”, with derivatives meaning “place or thing that is standing”, oldest form: * steh , colored to * stah , contracted to * sta- . Also origin of Greek eaTnv “I stood”, Sanskrit stha “to stand”. (For numerous related words in English, see Watkins 2011: 86b-87b.)

Line 4: Bards is from Welsh barrd and Gaelic Irish bard , origin of Greek βάρδος. In Latin, the term bardus is found in Lucan. The word was originally used in reference only to Celtic poets and, in lowland Scotland, to wandering minstrels; the meaning was later extended for general reference to poets. Although both the New English Dictionary (Oxford

ВЕСТНИК 2016

ВЕСТНИК 2016

1884) and the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford 1971) indicate that the earliest documentation of the word is from the mid-fifteenth century, Bard had already become a surname by the end of the thirteenth century. Cf. Scottish surname Baird . The Indo-European root is * gwera - “to favor”. Celtic * bardo refers to a “praise poet”, one who produced and bestowed praise poetry as gratification to his patron.

Line 5: expanse is related to the Latin verb ex-pandere , from pandere , pans - “to spread”. The Indo-European root is * peta - “to spread”, also the origin of Old English fœthm “fathom”, from Germanic * fathmaz “length of two arms extended”. There are numerous derivatives from Latin patere “to be open” and pandere (past participle passus < * patto -) “to spread out”, as well as from Greek πέταλον, “thin plate”, neuter of πέταλος, origin of French pétale and English petal , πατανέ (?<*πετάνα [petanā] > Latin patina ) “platter” and πέτασος “broad-brimmed hat”.

Line 5 begins with “Oft” in the manuscript, with “But” in the first published version. The former emphasizes the frequency of a certain special reference to Homer, the latter contrasts Homer’s domain with that of other literary references in the sonnet.

Line 6: low brow’d changed to deep brow’d. The word ‘low’ has meanings similar to those of ‘deep’: “deep browed” (or “low browed”) implies profound knowledge and intellectual powers. The term lowbrow (based on highbrow ) in the sense of ‘unsophisticated’ or ‘trivial’, is documented beginning in the early 20th century. In general, “brow”3 refers to the ridge above the eyes, also to “conte-nence”. The Indo-European root is * bhru - “eyebrow”, contracted from * bhruh , which yielded Middle English browe , from Old English bru -, via Germanic * brus . Related forms include Icelandic brun and, from other branches of the Indo-European family, Lithuanian bruwis , Russian «бровь», Greek бфрпд, Persian abru , Sanskrit bhru .

Line 6: demesne refers to “possession of own land”. The term entered English in the fourteenth century, via Old French demeine “belonging to a lord”, from Latin dominus “lord” (allied to verb domare “to tame”), dominicus “pertaining to a lord”, also the source of English domain , a more modern form, from the 15th century French domaine through alteration of demeine ‘demesne’, source of English demesne (ultimately from Indo-European * dem - “house, household”, with reflexes in several branches, such as Greek δέμω, Old Irish pátir , Avestan dam , Armenian tun , Tocharian A tam -, Tochar-ian B tem -; Watkins 2011: 16b, Pokorny 198). Cf. Johnson 1755 q.v.

Line 7: mean (in both early draft of Ms. and in the earliest printed version of the sonnet, The Examiner, December 1, 1816) comes from Middle English menen, Old English mænan, Germanic *main-jan, hence allied to Icelandic kenna, Swedish känna, Danish kiende, all of which are utimately from IndoEuropean *mei-no- “opinion, intention”.

A later version (2011, see n. 1) has a different text for this line, ending with serene , from Latin serenus , via French, with the derivatives serenity , French sérénité and Latin serenitas used as honorific forms in certain titles. The use of serene (“Yet did I never breathe its pure serene”) is in accord with the reference to the Pacific , in the second and final simile in the sestet, in comparison with the experience of reading Chapman’s translation of Homer, “till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold”. Both the early manuscripts and the first printing indicate the unique nature of the experience (“Yet could I never...”). The Indo-European root is * ksero - “dry”.

Line 10: planet is from Middle English plan-ete < Old French planete < Latin planeta < Greek πλανής “a wanderer”, plural πλάνητєς “wandering stars, planets”, from Indo-European root * peb- “flat; to spread”, also ultimate origin of поле “field” in Russian, Ukranian, Belorussian, Bulgarian and Macedonian, pole in Polish, Czech, and Slovakian, polje in Serbian and Slovenian, in addition to other related words of Slavic languages, such as Polanie (in reference to Polish people), literally “dwellers of the field” (i.e., Poland).

Line 10: ken, meaning “can” and “know” is from Anglo-Saxon cennan. Cognate forms are well attested in the Germanic languages: German ken-nen , können , Dutch kennen , Old Norse kenna , Gothic kannjan “to make known”. The root is from IndoEuropean * gno- “to know” (oldest form * gneh -, altered to * gnoh -, contracted to * gno -), also origin of Latin gnarus “one who knows” (with numerous derivations and compounds) and its antonym ignarus , as well words in other branches of IndoEuropean; Hellenic: Classical Greek: γνωσ- root of “to know” and related words, such as the coinages gnosis , from γνώσις in the sixteenth century, and agnostic , based on άγνωστος (suggested in Acts xvii: 23), by Huxley in 1869; Avestan zainti “knowledge”. (Watkins 2011: 33b, Pokorny 2 gen -, gena -, gne -, gno -, 376.)

Line 15: wild, meaning here “unrestrained, frenzied, full of intense emotion, bewildered”, is ultimately from the Indo-European root *welt- “woods, wild”, which yielded forms such as Old English weald, wald, from Germanic *walthuz; wild from Old English wilde, wild, derived from Germanic *wilthja-. Cognate forms in other Germanic languages include Dutch wild, Icelandic villr, Danish and Swedish vild, German wild, Gothic wiltheis. (In Pokorny 4. ǔel- 1139.)

Line 15: surmise, meaning “guess or notion based on intuition or limited information”, is based on * mittere “to let go, send off, throw”, of uncertain origin, with the likely oldest form being * smittere , as in the archaic spelling cosmittere , of the Classical Latin compound committere “to bring together”. (Watkins 2011: 57b, Pokorny * smeit - 968.) The English verb surmise comes from Latin mittere via Old French surmise , feminine singular of the past participle of surmettre . The original sense in English is that of supposing or conjecturing, to which the meaning of Keats’s phrase wild surmise clearly indicates. The component sur - recalls brow , from line 6.

In terms of punctuation and the use of capitalization, there is close affinity between the formal features of manuscript shown above and those or the version of the sonnet as first published in The Examiner on December 1, 18161. Many of the capital letters of the manuscript (– although not all...) are preserved in the initial publication of the sonnet. The uses of capitals in the manuscript is more extensive, including words that take the place of proper nouns, as well as some for emphasis. The punctuation is similar: both divide the octave into just two sentences, of four lines each, and both treat the sestet as a single sentence. It can be noted, however, that later publications have more differences, in relation to the texts considered here, with regard to the use of both punctuation and capitalization, with the later publications tending to be increasingly conservative with regard to pedagogical norms (hence, reflecting to a lesser degree the features of earlier versions)2.

Keats’s generation was familiar with the translations by John Dryden and Alexander Pope, in blank verse or heroic couplets, rendering Homer in a way similar to Virgil.

From the content of the sonnet, it is evident that Keats was profoundly impressed by Chapman’s rendition. Keats had a special affinity with Chapman: both had good knowledge of classical culture, both were poets and Keats also translated a classical epic poem.

Formally, Keats’s poetic tribute to Chapman is a sonnet in the style of Petrarch, consisting of an octave and a sestet, in iambic pentameter. The meanings of the parts are closely interrelated. That the manuscript is a draft (rather than merely a copy) is indicated both by the change in the text (line 6) and by marks connecting paired lines.

It is clear the “realms of gold” refers to literary riches, as evidenced by the successive references, in the first eight lines, to the Aegean islands, to Apollo (god of poetry, born at the sacred island of Delos, in the Aegean), to Homer, then to Chapman, preceded by “Yet could I never know what Men could mean”, which calls attention to the value of literary translation in making works available to those who otherwise would not have access to them, and especially to the value of quality in translation. The sestet concerns the magnitude of the experience of the first reading of Chapman’s translation, through two comparisons: first with taking knowledge of a new planet, then with an initial sighting of the Pacific.

Keats’s generation knew of the discovery of Uranus, the first planet to become known in modern times (not known in antiquity). Uranus (named after the Greek god ruler of the heavens) had been found fortuitously by Herschel in 1781. The phrase “swims into his ken” suggests the mode of the discovery (– contrary to the case of Neptune, to be discovered more than half a century later, through mathematical calculations, in 1846). Literary connections with the planet Uranus include the names of its seventeen satellites, all for characters in Shakespearean plays.

The second and final comparison is with the initial viewing of the Pacific Ocean by Cortez with “eagle eyes” (as shown in Titian’s painting of this subject), changed from “wond’ring eyes”, hence denoting close attention, in addition to the wonderment indicated by “wild surmise” and “silent”), while “all his men look’d at each other in wild surmise”. The two comparisons show the vastness of the discovery and the nature of its impression.

There are several links between words of like meaning, such as “Realms” (line 1), “King dom s” (line 2) and “Demesne” [= dom ain] (l. 6), or between the reference to the Aegean Islands (l. 3), sug-

ВЕСТНИК 2016

ВЕСТНИК 2016

gesting water, extended through the use of “swim” (l. 10), culminating in the reference to the aweinspiring Pacific Ocean, and between the vastness suggested by the use of wide expanse (l. 5) , the reference to a planet (l. 10), the reference to the Pacific (l. 12). Such connections contribute to the emphasis and unity of the poetic composition. The climactic impression made by the total imagery of the paired comparisons is one of awe, imposing silence.

Список литературы Keats’s sonnet on Chapman’s translation of Homer: early draft of manuscript and initial publication

- Johnson, Samuel. A dictionary of the English language: in which the words are deduced from their originals, and illustrated in their different significations by examples from the best writers. To which are prefixed, a history of the language, and an English grammar. -London, Printed by W. Strahan, 1755. (Fac-simile edition: New York: AMS Press, 1967.)

- Keats, John. Manuscript: Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold. A. MS., early draft, MS Keats 2.4. -Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.

- Keats, John. "On first looking into Chapman’s Homer"//The Examiner. -1816. -1 December. -p. 762.

- Keats, John. Poetical Works. -Oxford: University Press, 1992.

- Skeat, Walter W. A Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. -New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1980.

- Pokorny, Jules. Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. -Bern, München: Francke Verlag, 1959.

- Watkins, Calvert. The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. -3rd edition. -Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, 2011.