Клеточные маркеры воспаления в крови у пациентов с глиомами различной степени злокачественности

Автор: Скляр С.С., Нечаева А.С., Улитин А.Ю., Мацко М.В., Олюшин В.Е., Самочерных К.А.

Журнал: Сибирский онкологический журнал @siboncoj

Рубрика: Клинические исследования

Статья в выпуске: 5 т.24, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Клеточные маркеры воспаления, являющиеся ключевыми медиаторами иммунного ответа, уже продемонстрировали свою прогностическую значимость при различных онкологических заболеваниях. Однако их роль в патогенезе и прогрессировании глиом остается неизученной. Цель исследования – оценить диагностическую ценность данных биомаркеров при разных гистологических типах глиом и различных степенях их злокачественности. Материал и методы. В исследование включено 139 пациентов с впервые диагностированными диффузными глиальными опухолями взрослого типа супратенториальной локализации. Стратификация пациентов проводилась по степени злокачественности опухоли, наличию мутации в генах IDH1/2 и коделеции 1p19q. Согласно гистологической верификации, в когорте выявлено 25 случаев диффузной глиомы grade 2, 25 случаев диффузной глиомы grade 3 или 4, у 89 пациентов верифицирована глиобластома. Анализировались наличие сопутствующих заболеваний, текущая медикаментозная терапия, включая применение глюкокортикостероидов, молекулярно-генетические и морфологические особенности опухоли. В предоперационном периоде выполнялся развернутый клинический анализ периферической крови с определением абсолютных показателей моноцитов, нейтрофилов, лимфоцитов, а также значений клеточных маркеров воспаления (NLR (нейтрофильно-лимфоцитарное соотношение), LMR (лимфоцитарно-моноцитарное соотношение), PLR (тромбоцитарно-лимфоцитарное соотношение). Результаты. Значение LMR в группе с глиомой grade 2 было выше, чем у пациентов с глиомой grade 3, 4 и глиобластомой (3,71 vs 3,09 vs 3; p<0,05) с площадями под кривой (AUCs) of 0,6552 (0,4930–0,8174) и 0,6586 (0,5583–0,7590) соответственно. Выявлены значимо более высокие показатели LMR у пациентов с глиомами с наличием мутаций IDH1/2 по сравнению с IDH-wild type (3,44 vs 3,0; p=0,039). Примечательно, что терапия ГКС не оказала существенного влияния на уровень LMR ни в одной из исследуемых подгрупп. При глиобластомах уровень NLR был выше, чем у пациентов с глиомами grade 2 (2,9 vs 1,96, p<0,05). Повышение уровня NLR прямо коррелировало с назначением ГКС (3,7 vs 8,0, p<0,05 и 1,95 vs 3,79, p<0,05, respectively). При статистическом анализе определена положительная корреляция между применением ГКС и повышением NLR в группах пациентов с глиобластомой и глиомами grade 2 (3,7 vs 8,0, p<0,05 и 1,95 vs 3,79, p<0,05, соответственно). Заключение. Полученные данные позволяют рассматривать LMR в качестве перспективного, дополнительного, не зависящего от назначения ГКС, диагностического биомаркера при диффузных глиомах взрослого типа. С повышением степени злокачественности регистрировалось уменьшение LMR. NLR не является достоверным диагностическим показателем. Увеличение данного биомаркера сопряжено с назначением пациентам ГКС, что снижает его ценность.

Церебральные опухоли, глиомы, маркеры воспаления, lMR

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140312762

IDR: 140312762 | УДК: 616-006.484+616-002+616.155.32 | DOI: 10.21294/1814-4861-2025-24-5-40-52

Текст научной статьи Клеточные маркеры воспаления в крови у пациентов с глиомами различной степени злокачественности

According to global epidemiological data, approximately 320,000 new cases of primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors are diagnosed every year, with an estimated mortality of about 250,000 patients affected by these neoplasms [1]. Among primary intracerebral tumors, diffuse gliomas are the most common subtype [2]. The 5th edition of the WHO classification of CNS tumors categorizes astrocytomas as grades 2, 3, and 4, oligodendrogliomas as grades 2 and 3, and gliob- lastomas as grade 4 [3]. Notably, all grade 2gliomas are classified as low-grade tumors; conversely, grade 3 and 4 diffuse gliomas as well as glioblastomas, are associated with a significantly poor prognosis and are classified as malignant neoplasms.

Treatment of diffuse glioma patients includes neurosurgical procedures, adjuvant radiation therapy and systemic anti-tumor therapies, including chemotherapy and targeted therapy [4, 5]. It is important to note that the specific anti-tumor regimen is not only adapted to the histological subtype of diffuse glioma but is also strongly influenced by the extent of resection [4]. The extent of tumor resection can substantially impact the necessity for subsequent anti-tumor therapy, particularly in cases of low-grade diffuse glioma. For histological classifications such as grade 3 and 4 astrocytomas, grade 3 oligodendrogliomas and glioblastomas, radiation and chemotherapy are required regardless of surgical outcome. Although glioblastoma has distinctive radiographic characteristics, it is often difficult to differentiate diffuse gliomas of varying grades of malignancy using MRI data. Therefore, there is an urgent need for pre-operative confirmation of histological diagnosis to facilitate optimal neurosurgical planning and comprehensive treatment of the patient.

Advanced imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) have been developed in recent years and have made it easier to improve the accuracy of pre-operative diagnostics [6, 7]. Liquid biopsy has proven to be a very promising diagnostic approach in general oncology and neuro-oncology [8]. Circulating nucleic acids have been identified as having significant diagnostic potential in gliomas of different malignancies [9]. However, the high costs associated with these techniques limit their availability in many health care settings. Therefore, there is still a critical need for a cost-effective, rapid and unambiguous method of differential diagnosis of brain gliomas.

Research suggests that systemic immune inflammation plays a key role in the oncogenic process [10–12]. The primary focus of the study was to assess the local immune response within tumors. Reprogrammed immune cells have been shown to contribute approximately 30 percent of the cellular composition of malignant gliomas, facilitating tumorogenesis [13]. In addition, intracellular inflammatory signaling pathways were clarified and key cytokines were characterized. However, research on systemic immune inflammation in gliomas is still in its early stages and should be further explored.

Numerous studies have been carried out to evaluate the diagnostic and prognostic relevance of cellular inflammatory markers in patients with glioma [14–18]. It should be stressed that most of these studies did not stratify tumors according to histological classification and grade of malignancy. Moreover, the existing literature largely ignored the effect of glucocorticoster- oid (GCS) therapy on patients, despite its significant impact on the dynamics of the immune system. The prognostic effects of inflammatory biomarkers in patients with glioblastoma have been previously assessed, including the effects of GCS [19].

This study aimed to assess the diagnostic utility of systemic inflammatory markers – including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) – across histological subtypes and malignancy grades of glioma, with particular consideration of GCS.

Material and Methods

The research involved 139 patients, all newly diagnosed with supratentorial adult-type gliomas. Patients underwent surgery in the Department of Brain and Spinal Cord Tumor Surgery at the National Research Medical Centre of Almazov in the period from 2021 to 2024. Before being included in the study, informed consent was obtained from each of the participants. The exclusion criteria included diagnosis of immunodeficiency, autoimmune disease or neoplasms outside the central nervous system.

The study also excluded individuals who had previously undergone radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy. Each patient included in the research was assessed by a team of specialists: a general practitioner, otolaryngologist, dentist and neurologist. The presence of acute or chronic inflammatory conditions during the period of exacerbation, use of antibacterial agents and antibiotics at the time of enrolment and continued treatment with anticonvulsants were also considered disqualifying factors.

Venous blood samples were collected from patients three days prior to surgical intervention in the morning, followed by a comprehensive clinical haematological examination and the quantification of C-reactive protein (CRP). Patients with CRP levels above 5 ng/ml were excluded from the study cohort. Clinical haematological analysis, including extended leukocyte differentiation, was performed with the use of the Sysmex XN-550 haematological analyser, using Sysmex reagents and control materials sourced from Japan. Inflammatory markers, including the NLR, LMR and PLR, were calculated from absolute counts of lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets to evaluate the systemic inflammation in neuro-oncologic diseases.

The study included only patients who underwent scheduled neurosurgical interventions. Histopathological diagnosis was made by analyzing surgical tumor samples according to standardized criteria described in the Fifth Edition of the World Health Organisation Central Nervous System Tumor Classification [3]. Histological sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, in addition to immunohistochemistry (IHC) panels including anti-GFAP (poly, DakoCytomation), anti-ATRX (Abcam), anti-EGFR (Abcam), antiMGMT (NovusBiologics), anti-Ki-67 (Dako), anti-

IDH1R132H (Dianova), and for differential diagnosis Syn (DakoCytomation) and NB (Leica), CD99 (12E7, DakoCytomation). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to assess for the presence of a 1p/19q codeletion. FISH was performed using two-color DNA probe test systems to detect deletions of the SRD (1p36) (Cytocell) and GLTSCR1 (19q13) (Fast Probe, Wuhan Healthcare) genes. Mutational analysis of the IDH1 (exon 4) and IDH2 (exon 4) genes was performed via high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA) of PCR products, followed by subsequent DNA sequencing to elucidate genetic alterations. The prepared specimens were viewed and evaluated by two independent pathologists. The final diagnosis was made by a multidisciplinary team including a pathologist, an oncologist, a neurosurgeon and a radiologist, based on the results of a molecular-histological conclusion of the biopsy material, taking into account the clinical course of the disease, the radiological appearance and the macroscopic intraoperative features of the tumor.

Statistical analysis was performed using thePrism GraphPad 10 program (GraphPad Software, USA). The normality test was performed using Kolmogorov– Smirnov, Shapiro–Wilk tests. We used the mean ± standard deviations for normally distributed data, and median (rank) for non-normally distributed data. Nonparametric group comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test. The diagnostic accuracy of preoperative inflammatory markers was evaluated using ROC curve analysis, with AUC quantification. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The resulting graphs were performed using the Prism GraphPad 10 program (GraphPad Software, USA).

Results

Patients were stratified into three cohorts based on histopathological classification: grade 2 glioma (n=25, of them 7 with oligodendroglioma), IDH1 mutated grade 3 and 4 gliomas (n=25, of them 8 with oligodendroglioma), and glioblastoma (n=89) (Table 1).

The grade 2 glioma and grade 3 and 4 glioma (IDH1-mt) cohorts also included patients diagnosed with oligodendroglioma (7 and 8 patients, respectively). Notably, patients exhibiting IDH1-positive tumor status in grades 2, 3, and 4 glioma were significantly younger than those diagnosed with glioblastoma (Table 1). The mean age of patients with grade 2 glioma was 42.5 ± 12.5 years, comprising 14 (56 %) males and 11 (44 %) females. Conversely, the mean age of patients with 3 and 4 glioma (IDH1-mt) was 46 ± 11 years, with 7 males (28 %) and 18 females (72 %). In the glioblastoma cohort, the mean age was 60 ± 12.5 years, with 51 (57.31 %) males and 38 (42.69 %) females.

A significant proportion of patients diagnosed with grade 2 and grade 3 gliomas did not receive glucocorticoid therapy (dexamethasone) prior to surgery, with rates of 76 % and 56 %, respectively. In contrast, in the glioblastoma cohort, only 25.85 % of cases were not administered glucocorticoids, as shown in Table 1.

Comparison of preoperative inflammatory blood markers for glioma of different subtypes

There were no statistically significant differences observed in lymphocyte, platelet, or platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) levels across the three studied cohorts (Fig. 1b, 1d, and 1g). Notably, the counts of neutrophils and monocytes in grade 2 glioma cohort

Table 1/Òàблицà 1

Preoperative characteristics of 139 patients with cerebral gliomas

Õàðàêтåðиñтиêи 139 пàциåнтîв ñ цåðåбðàльными глиîмàми нà дîîпåðàциîннîм этàпå лåчåния

|

Parameters/Параметры |

Grade 2 glioma/ Глиома grade 2 (n=25) |

Glioma grade 3, 4 IDH-mutant/ Глиома grade 3, 4 с мутацией IDH (n=25) |

Glioblastoma/ Глиобластома (n=89) |

|

Age, years/Возраст, лет |

42.5 ± 12.5b |

46 ± 11b |

60 ± 12,5 |

|

Male/Муж |

14 (56 %) |

7 (28 %) |

51 (57.31 %) |

|

Female/Жен |

11 (44 %) |

18 (72 %) |

38 (42.69 %) |

|

Taking dexamethasone/Принимают дексаметазон |

|||

|

Yes/Да |

6 (24 %) |

11 (44 %) |

66 (74.15 %) |

|

No/Нет |

19 (76 %) |

14 (56 %) |

23 (25.85 %) |

|

Laboratory dates/Лабораторные |

показатели |

||

|

Neutrophils/Нейтрофилы (×109/L) |

4.01 (1.54–15.0)b |

5.30 (1.53–16.80) |

7.42 (1.85–24) |

|

Lymphocytes/Лимфоциты (×109/L) |

2.11 (1.20–4.0) |

2.0 (1.01–2.7) |

2.07 (0.66–4.82) |

|

Monocytes/Моноциты (×109/L) |

0.52 (0.2–1.50)b |

0.60 (0.01–2.1) |

0.81 (0.2–2.0) |

|

Platelets/Тромбоциты (×109/L) |

226 (158–401) |

268 (108–408) |

245 (117–487) |

|

NLR |

1.96 (0.64–8.30)b |

2.0 (0.76–16.63) |

2.9 (0.62–34.25) |

|

LMR |

3.71 (2.4–9.230)a–b |

3.09 (0.99–8.33) |

3.0 (0.53–8.48) |

|

PLR |

104 (49.58–199.2) |

114 (70.13–348.5) |

117 (32.05–358.9) |

Notes: mt – mutant; a – vs grade 3,4 (IDH1-mt) (p<0.05); b – p<0.05 vs glioblastoma (p<0.05); created by the authors.

Примечания: mt – мутация; a – по сравнению с глиомами grade 3, 4 (IDH1-mt) (p<0,05); b – по сравнению с глиобластомами (p<0,05); таблица составлена авторами.

Table 2/Òàблицà 2

Preoperative inflammatory markers and dexamethasone intake in glioma patients Пðåдîпåðàциîнныå мàðêåðы вîñпàлåния и пðиåм дåêñàмåтàзîнà ó пàциåнтîв ñ глиîмîé

|

Parameters/ Параметры |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3,4 (IDH-mt) |

Glioblastoma/Глиобластома |

|||

|

Without dexamethasone/ Без дексаметазона (n=19) |

With dexamethasone/ С дексаметазоном (n=6) |

Without dexamethasone/ Без дексаметазона (n=14) |

With dexamethasone/ С дексаметазоном (n=11) |

Without dexamethasone/ Без дексаметазона (n=23) |

With dexamethasone/ С дексаметазоном (n=66) |

|

|

Neutrophils/ |

3.43 |

5.20 |

4.0 |

10.0 |

3.70 |

8.0 |

|

Нейтрофилы (×109/L) |

(1.54–11.69) |

(4.40–9.6) |

(1.53–5.52) |

(3.05–16.80)a |

(1.85–7.55) |

(2.14–24)b |

|

Lymphocytes/ |

2.0 |

3.48 |

2.0 |

2.20 |

1.76 |

2.18 |

|

Лимфоциты (×109/L) |

(1.20–3.25) |

(2.06–4.0) |

(1.20–2.5) |

(1.01–2.7) |

(1.10–4.70) |

(0.66–4.82) |

|

Monocytes/ |

0.50 |

0.57 |

0.52 |

0.72 |

0.59 |

0.82 |

|

Моноциты (×109/L) |

(0.20–1.0) |

(0.39–1.50) |

(0.30–2.10) |

(0.01–1.21) |

(0.20–1.0) |

(0.23–2.0) b |

|

NLR |

1.86 (0.64–3.56) |

2.1 (1.37–2.59) |

1.86 (0.76–4) |

5 (1.15–16.63)a |

1.95 (0.62–5.0) |

3.79 (0.80–34.35)b |

|

LMR |

3.75 (2.4–9.23) |

3.74 (2.47–8.33) |

3.1 (0.99–6.67) |

2.5 (1.0–4.58) |

3.6 (1.3–8.2) |

2.88 (0.53–8.48) |

Notes: mt – mutant, a – vs glioma grade 3,4 (IDH1-mt) without dexamethasone (p<0.05); b – vs glioblastoma without dexamethasone (p<0.05); created by the authors.

Примечание: mt – мутация; a – по сравнению с глиомами grade 3,4 (IDH1-mt) без дексаметазона (p<0,05); b – по сравнению с глиобластомами (p<0,05); таблица составлена авторами.

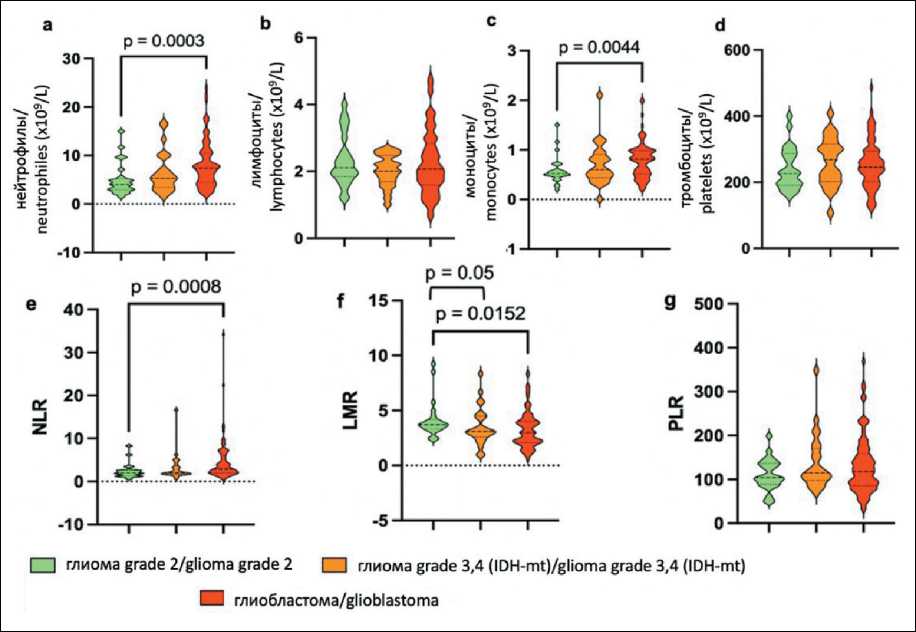

Fig. 1. Violin diagram illustrating the distribution of preoperative inflammatory marker levels in different grades of glioma groups. Notes: the central dashed line indicates the median value, while the flanking dashed lines demarcate the first and third quartiles; a – neutrophils, b – lymphocytes, c – monocytes, d – platelets, e – NLR, f – LMR; g – PLR; created by the authors

Рис. 1. Диаграмма, иллюстрирующая распределение предоперационных уровней маркеров воспаления в различных группах глиом grade 2, 3 и 4 (IDH1-mt) и глиобластом. Примечания: центральная пунктирная линия указывает на среднее значение, в то время как боковые пунктирные линии разграничивают первый и третий квартили; а – нейтрофилы, в – лимфоциты, с – моноциты, d – тромбоциты, e – NLR, f – LMR, g – PLR; рисунок выполнен авторами

[4.01 (1.54–15.0) and 0.52 (0.2–1.50), respectively] were significantly lower compared to those in the glioblastoma cohort [37.42 (1.85–24) and 0.81 (0.2– 2.0), respectively] (Fig. 1a, 1c).

The analysis revealed that the NLR and LMR exhibited no significant differences between grade 3 and 4 glioma (IDH-mutant) and glioblastoma groups. Notably, the LMR was found to be significantly higher in the grade 2 glioma group with a mean value of 3.71 (range: 2.4–9.230) than in the grade 3 and 4 glioma (IDH-mutant) and glioblastoma groups (3.09, range: 0.99–8.33 and 3.0 (range: 0.53–8.48), respectively (Fig. 1f). Conversely, the highest NLR values were recorded in glioblastoma patients, with a mean of 2.9 (range: 0.62–34.25), demonstrated a statistically significant difference compared to the NLR in low-grade glioma patients, which was 1.96 (range: 0.64–8.30) (Fig. 1e).

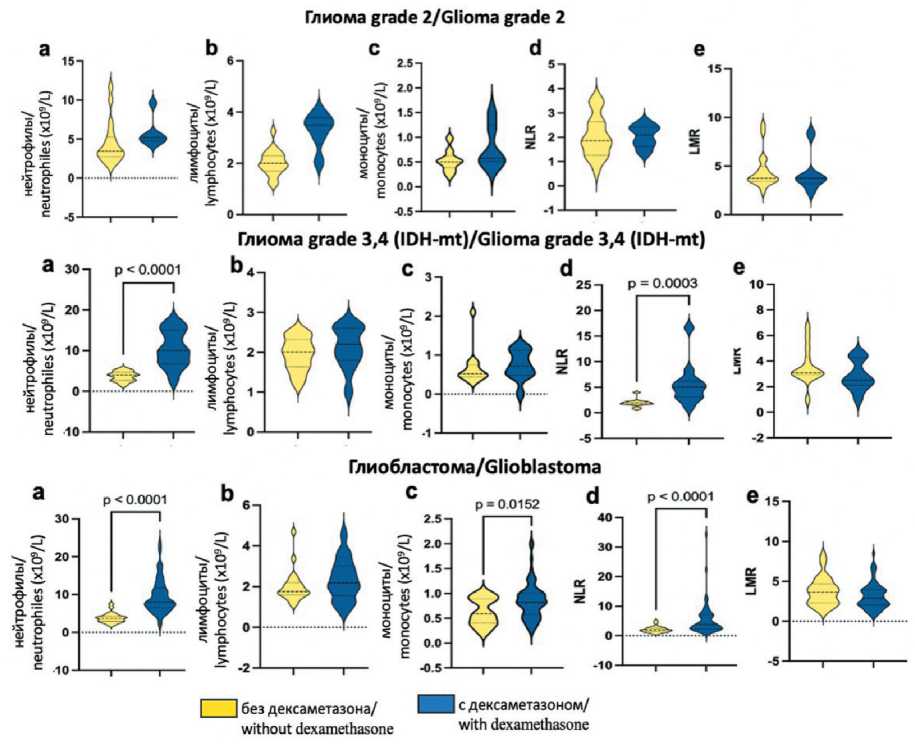

The analysis of hematological parameters, specifically neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, NLR and LMR, was conducted in relation to the administration of GCS prior to surgical intervention (Table 2). In patients receiving GCS, a statistically significant elevation in neutrophil counts was observed in the grade 3 and 4 glioma and glioblastoma cohorts (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, NLR values were markedly increased in patients with gliomas undergoing treatment with dexamethasone (Fig. 2d). The administration of dexamethasone was found to influence monocyte levels exclusively in the glioblastoma patient group (Fig. 2c). Notably, the LMR index exhibited no significant variation between patients receiving dexamethasone and those who were not across all three patient categories (Fig. 2e).

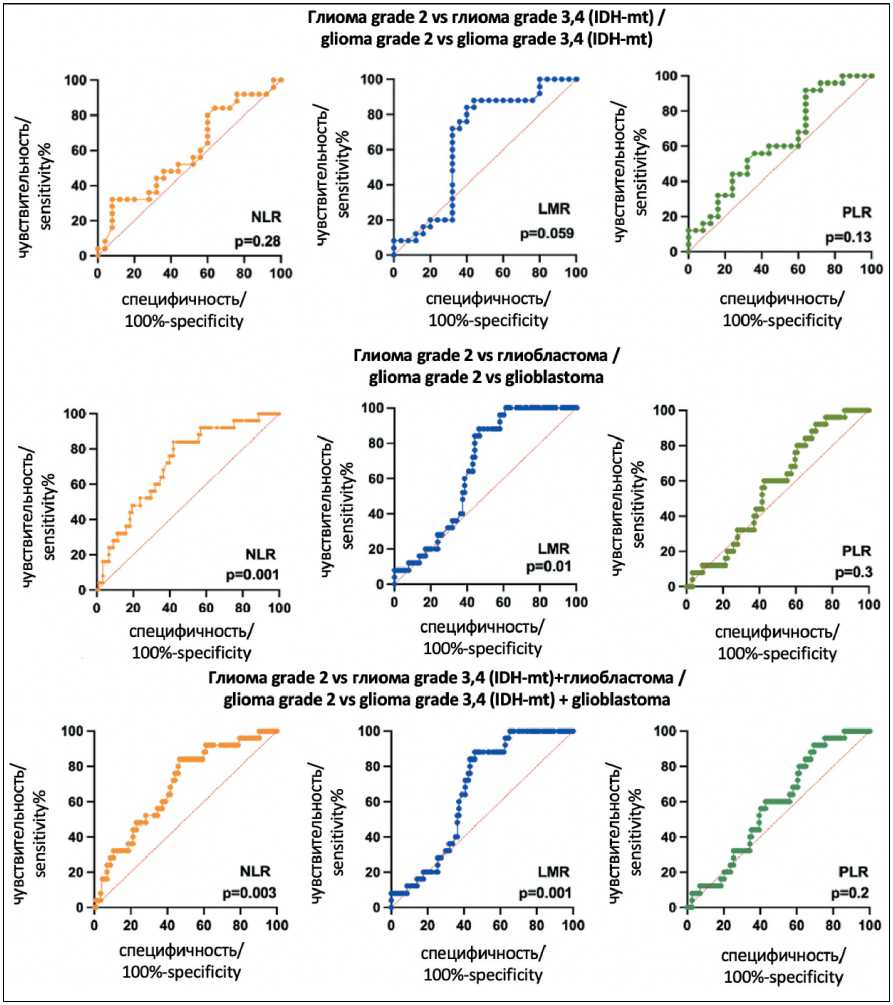

Diagnostic value of inflammatory blood markers in glioma diagnosis and glioma grading

According to the ROC analysis, two biomarkers showed significant diagnostic value: NLR and LMR (Fig. 3). The optimal ratio of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of grade 2glioma compared to glioblastoma was observed for NLR value <2.5 (72.0 % and 61.3 %, respectively) and for LMR >3.57 (64 %

Fig. 2. Violin diagram comparing preoperative inflammatory marker levels across glioma grades, stratified by dexamethasone administration status. Notes: central lines represent medians, with outer boundaries indicating interquartile ranges;

a – neutrophils, b – lymphocytes, c – monocytes, d – NLR, e – LMR; created by the authors

Рис. 2. Диаграмма, на которой сравниваются уровни дооперационных маркеров воспаления в зависимости от гистологического подтипа глиомы и приема дексаметазона. Примечания: центральные линии представляют медианы, внешние границы указывают на межквартильные интервалы; а – нейтрофилы, в – лимфоциты, с – моноциты, d – NLR, e – LMR; рисунок выполнен авторами

and 59 %, respectively). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.7157 (95 % CI: 0.6087–0.8227) for NLR and 0.6586 (95 % CI: 0.5583–0.7590) for LMR, which characterized the quality of the model as satisfactory (Table 3, Fig. 3). However, NLR values were influenced by the administration of GCS (Table 2), whereas LMR was unaffected by this therapeutic intervention, establishing LMR as a more robust independent marker. When differentiating the diagnosis of grade 2 glioma from more aggressive glial tumors (grade 3 and 4 with IDH1 mutation and glioblastoma), the optimal ratio of sensitivity and specificity (72 % and 58 %, respectively) was observed at LMR levels >3.4 (AUC 0.6579, 95 % CI: 0.5635–0.7522). In the differential diagnosis of grade 2 glioma from grade 3 and 4 glioma with IDH1 mutation, satisfactory sensitivity and specificity (72 % and 68 %, respectively) were also maintained at LMR > 3.4 (AUC 0.6552, 95 % CI: 0.4930–0.8174). The study showed that LMR, compared with other cellular biomarkers, has significant diagnostic value for patients diagnosed with low-grade glioma.

Fig. 3. The diagnostic value of preoperative inflammatory markers in glioma diagnosis. Grade 2 glioma vs grade 3 and 4 glioma (IDH-mt), grade 2 glioma vs glioblastoma, grade 2 glioma vs grade 3 and 4 glioma (IDH-mt) + glioblastoma.

Notes: created by the authors

Рис. 3. Диагностическая ценность предоперационных маркеров воспаления в диагностике глиомы. Глиомы grade 2 vs глиомы grade 3, 4 (IDH-mt); глиома grade 2 vs глиобластомы; глиома grade 2 vs глиомы grade 3, 4 (IDH-mt) + глиобластома.

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами

Table 3/Таблица 3

Diagnostic value of various inflammatory markers in glioma diagnosis Диагностическая ценность различных маркеров воспаления в диагностике глиомы

|

Grade 2 vs grade 3, 4 |

|||

|

Markers/ |

Grade 2 vs grade 3,4 (IDH-mt) |

Grade 2 vs glioblastoma/ Grade 2 vs глиобластома |

(IDH-mt) + glioblastoma/ Grade 2 vs grade 3, 4 |

|

Маркеры |

AUC (95 % CI) p-value |

AUC (95 % CI) p-value |

(IDH-mt) + глиобластома AUC (95 % CI) p-value |

|

NLR |

0.5888 (0.4292–0.7484) |

0.28 |

0.7157 (0.6087–0.8227) |

0.001 |

0.6876 (0.5798–0.7954) |

0.003 |

|

LMR |

0.6552 |

0.059 |

0.6586 |

0.01 |

0.6579 |

0.001 |

|

(0.4930–0.8174) |

(0.5583–0.7590) |

(0.5635–0.7522) |

||||

|

PLR |

0.6232 |

0.13 |

0.5676 |

0.30 |

0.5798 |

0.20 |

|

(0.4670–0.7794) |

(0.4546–0.6807) |

(0.4708–0.6888) |

Notes: AUC – Area Under the ROC Curve; created by the authors.