Кто "успешный" мигрант? (Некоторые заметки о социальной дифференциации в эмигрантском сообществе в Китае)

Автор: Итое Канеширо

Статья в выпуске: 1, 2013 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Эта работа раскрывает социальные различия, которые привносит в родную китайскую деревню иммигрантский «успех». Автор иллюстрирует ситуацию вокруг миграции, освещает и анализирует образ «успешных» иммигрантов в глазах родной деревни, также как нормы поведения, ожидаемые от этих иммигрантов.

Эмигрант, успех, социальные различия, китай

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148315700

IDR: 148315700 | УДК: 314.743

Текст научной статьи Кто "успешный" мигрант? (Некоторые заметки о социальной дифференциации в эмигрантском сообществе в Китае)

The purpose of this paper is to clarify the social differences that immigrants’ ‘success’ bring to their native village in China. In order to do so, I first illustrate the situation surrounding migration in the surveyed area and then elucidate and analyze the image of ‘successful’ immigrants in the eyes of native villagers as well as the code of conduct expected from these immigrants.

At first, from the viewpoint of movement to the foreign countries, the people who living in South China is the highest move to the foreign countries than other people who living in China. South China is known as these areas make use of a geographical advantage to be near to the sea, and having performed overseas trade frequently for a long time. And, this area has traditionally been a region of major emigration abroad. Especially, Fujian and Guangdong have a lot of emigrant communities which called «qiaoxiang( 僑郷 )» in Chinese.

To borrow Chen Ta’s phase, «emigrant community» is «an emigrant community …means a community from which considerable numbers of persons have for some time emigrated, and continue to emigrate abroad, non-emigrant community is one where such emigration is rare» [Chen Ta 1939:4, note 3]. In addition to this definition, Watson regarded «emigrant community» as «villag-es that have a high rate of international emigration as opposed to internal or rural-urban migration» [Watson 1979: 1]. So the word «emigrant community» in here I use is same mean as Watson’s view.

Past studies on emigrant communities in South-Eastern China have mainly focused on social change, identifying the impacts that immigrants have had on the traditional social structures of the emigrant community and the process of how village societies have responded to such shifts (for example, see Chen 1939, Watson 1995 [1975]). As expected, immigrants have had an enormous influence on village economy and society. These effects are evident in the changes in the economy and traditional social structures of farming communities (for example, Chen 1939). On the other hand, it was also noted that immigrants have become one of the forces maintaining the traditional social structures, and so called ‘conservative transformations’ (Watson 1995 [1975]) have been observed.

The enormous wealth brought to the homeland was one of the direct causes that led to these changes. In South-Eastern China during the period between the end of the Qing dynasty and the Republic of China, especially in the Guangdong and Fujian societies, restoring and maintaining shrines, graves and village infrastructure with one’s own funds was an important means to elevate one’s social prestige. This measure continues to be adhered to by the many immigrants who follow the same path today (1).

As we shall see through the discussion below, the influx of capital brought by the immigrants has changed the exterior look of emigrant community and contributed to creating an image of wealthy villages. However, when we look at what is occurring inside such villages, especially at the individual and family levels, we can observe disparities particularly in the level of financial income among families who have dispatched immigrants in the same manner.

While living in the village, I had many opportunities to hear about the financial situations of different households, which also often suggested the widening financial divide between ‘successful’ and ‘unsuccessful’ overseas immigrants. However, the villagers themselves rarely spoke directly of or compared each other’s income or assets. In fact, the villagers’ conversations suggested that their focus was more on how the acquired assets were consumed. Wealth was expended according to the village’s internal cultural code. Indeed, how the capital was used was an indicator in terms of the creation of a ‘successful’ immigrant image.

Based on this view, in this paper I illustrate how the wealth, acquired by the immigrants is consumed in the village’s social life and then discuss how the residents attempt to differentiate themselves from others. To begin with, I present an overview of our survey area, Village X in Fuzhou City, Fujian Province, then explain the background of why Village X began to dispatch immigrants, their destinations and the various situations surrounding immigrants, such as immigration methods. Based on this, I’d like to offer a glimpse of the economic and social condition of an emigrant community, and then examine villagers’ narratives about «successful emigrants» to explore how villagers conceive socio-economical gap.

-

2. Overview of the survey area

-

3. The immigrants’ situation in Village X

As previously stated, Village X has dispatched many overseas immigrants since the 1980s. There are two types of immigrants recognized in Village X: ‘immigrants based on legal measures’ and ‘immigrants based on illegal measures’. The latter in particular are known as toudu ( 偷 渡 ), and while their destinations spread to various regions of the world, in this paper I focus on immigrants to the US.

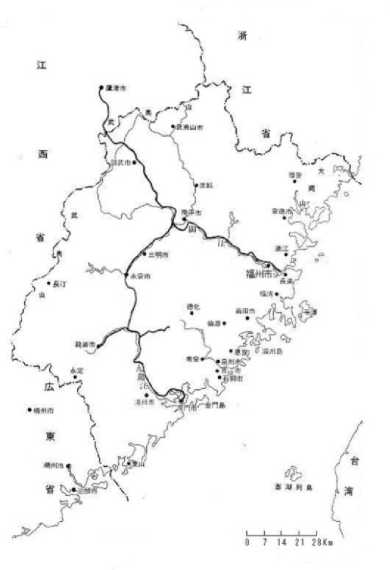

Fujian Province is located in the south-eastern part of China, bordering Zhejiang Province in the north, Guangdong Province in the southwest and Jiangxi Province in the west. Flat land is scarce in mountainous Fujian Province, but the coastal areas have flourished via domestic and overseas trading in the form of marine transport since the Song Dynasty. As farmland was limited, people did not hesitate to immigrate overseas to explore new opportunities when the population reached saturation point.

My survey area, Village X, is located in the township or zhen ( 鎮 ) T of Fuzhou City in the north eastern region of Fujian Province (Figure 1). Fuzhou City is the capital city of Fujian Province as well as its political and economic center. Fuzhou City is located in the coastal area and like many other cities, has flourished as a hub for marine transport trading. Village X is located near the mouth of Fujian Province’s largest river, Min River ( 閩江 ). Village X has a population of 4,152 with 1,447 households (Editorial Committee of Zhen Journal of Village X 2010). However, this figure simply shows the number of people registered as residents. As most immigrants do not deregister when they go overseas, the number of residents actually living in the village would be much smaller. I estimate the number of villagers who actually reside in the village to be around 2,000 through my conversations with the villagers. The majority of the residents are Han people and most speak the local dialect, but they also understand a certain amount of the Mandarin.

Figure 1 : Location of Fuzhou City

As described below, a large proportion of the residents of Village X have already left the village to work and live overseas or moved to other cities for job opportunities. The current population of Village X is mainly composed of the ‘elderly’, women, children and migrant laborers from the inner regions of China known as Waidiren ( 外地人 )(2). The village is equipped with a post office and banks offering foreign currency exchange services. The post office even has a small electronic bulletin board at the front where villagers can check the current exchange rate for US dollars. It is not rare to see people exiting with a large amount of yuan, which is another indication that the villagers’ livelihoods have a close relationship with overseas remittance funds.

Being surrounded by mountains on three sides, Village X was not an ideal location for agriculture with limited arable land. However, it had the advantage of being connected to the cities via rivers and developed itself as a hub for long distance trade from the end of the Qing Dynasty to the Republic era, while it also functioned as a market town servicing surrounding villages. From 1949 onwards, policies to increase farming productivity were introduced but failed to bring intended outcomes. Instead, most people relied on natural resources from the mountain and engaged in stone material processing. Today, we hardly see any business activities in the village. Some people raise livestock such as ducks and chickens for their own consumption and grow vegetables in small plots; however, these endeavors do not seem to be contributing to their income. In- stead, the unemployed, mostly comprised of the ‘elderly’, are busy with their ‘consumption’ lifestyles, spending time gambling and working on their hobbies.

While I was conducting interviews on immigrants in Village X, someone mentioned the phrase ‘Going (to the US) is stupid but not going is also stupid’. When I inquired what this meant, they told me that it was ironic that those who choose to spend a fortune to travel overseas are only met with tough days of hard labor. Then again, those who do not go when everyone else is going would lose their face or mei mianzi ( 没面子 ). A lot of villager choose toudu ( 偷 渡 ) to go to the US.

According to many informants, the reason why the residents of Village X began to aspire to go overseas was largely to do with poverty and conditions in the surrounding villages at the time. Following the socialistic policies enforced by the Chinese Communist Party since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Village X introduced various policies aimed at increasing agricultural productivity. However, they did not achieve a significant result as land was limited to begin with. The focus gradually shifted towards stone material processing, but people’s lives remained very tough. The informants who reflected on those days all said, ‘we did not have any possessions or food. We raised any livestock and cultivated any crops we could think of. Still, our life was really tough’. Once the reform and open policy was introduced, people in the coastal area of Fuzhou region, including the T zhen ( 鎮 ) region, began migrating to developed countries such as the US, Japan and the EU.

Years later, as the funds acquired by migrant workers gradually returned home, the infrastructure of the village was upgraded and luxurious common facilities and houses were built, giving the village a modern look. When one visits the villagers, one can see that not only are most households equipped with electrical appliances such as televisions: most elders use mobile phones and many even own personal computers. A lot of the elders seem to be communicating with their children and grandchildren in the US via the Internet and spend their leisure time gambling, playing mah-jong and cards, watching TV and chatting on the street. Households comprised of only elderly members often hire helpers called baomu ( 保姆 )(3) to do the household chores such as cooking and washing. This is why outsiders see the village as a ‘wealthy village’.

-

4. Conditions for ‘success emigrant’

-

5. Actions expected from a successful immigrant

When villager referred to «successful emigrants,» they seem to have certain measures of evaluation in their mind. The first determining factor is whether or not immigrants are financially stable. More specifically, have they repaid their travel expense debt and are they able to remit money back home? As we saw above, in many cases the purpose of immigration is to find means to alleviate poverty, so most villagers are not capable of saving the travel expenses themselves. In such cases, they borrow money from friends and relatives and repay the debt from the salary they get paid at their destination. Most people initially start off by working in China Town in New York City, and informants say that they can usually repay the travel debt within the first four years. Whilst repaying the debt, they start sending small sums back home once they begin accumulating surplus. The average sum or frequency of remittance in Village X is hard to grasp. Some seem to be making regular remittance while others send money only when it is needed for a particular purpose. The situation seems to vary on an individual basis.

The next important factor to take into account when determining whether or not the immigrant is successful is the immigrants’ ‘status’. When the villagers talk about immigrants, the presence or absence of a Green Card is the most frequently mentioned issue. Generally speaking, the residents of Village X immigrate through illegal measures, so they start off their lives in the US as illegal immigrants. Once they arrive in the US, they strive to achieve financial stability and to acquire a Green Card. Once they successfully acquire this certification, they can be freed from psychological and legal instability and as Shen indicates, the possibility of achieving financial security will increase as this brings many benefits such as greater occupational opportunities (Shen 2004). At the same time, the acquisition of a Green Card means that they can now return home. As explained later, the immigrants can show off their success on their first homecoming by inviting friends and relatives to a spectacular feast and offering various gifts.

A few years after acquiring a Green Card, immigrants can sit a test to obtain citizenship. Immigration of their families becomes significantly easier once they acquire US citizenship, so most people sit the test. When they successfully pass, not only do they acquire ‘American citizenship’, but also bestow a great honor on the family who has produced an immigrant of the highest ‘status’.

As we have seen above, immigrants’ success can first be confirmed through their financial stability and acquisition of status and it is considered ideal if their status allows them to return home or move without restrictions. From then on, there are a few actions that need to be taken to accentuate their success in the village. Let us now look at these measures.

5-1. The feast to be held upon their first homecoming

The immigrants who left the village between the 1980s and 1990s usually took more than five years to return home. Back then, they were not even sure if they would reach their destination safely. Therefore, news of safe arrival was greeted with great delight, worthy enough to take action such as the dedication of a theatrical play to the shrine. Also, when returning home, immigrants had to prepare various gifts in addition to paying for the return airfare. As returning home alone required large amounts of money, to be able to afford this was enough of an indicator to show that one had become fairly wealthy.

For example, Informant C (sixties, male) said:

When someone returned home in the 80s and the 90s, we used to have spectacular feasts. The immigrant himself acted as the host and invited friends and relatives to enjoy the reunion. He brought gifts from the US, such as Western liquor (whisky and wine) and tobacco. Sometimes cash was given out, not in yuan but, say, a $100 note in a little envelope. But homecoming has become quite common by the 2000s, especially in the last five to six years. People no longer have special feasts at homes but they still invite friends and relatives to a restaurant in a nearby town and offer gifts. These days, they bring us American medicine and household goods.

We can see here that homecoming required lots of preparation and cost a lot of money. As this informant said, homecoming had become such a common event by the 2000s that people no longer went to the trouble of hosting a large feast at home. However, they still invited their close friends and relatives to restaurants or offered various gifts.

5-2. Home renovation

As Watson (1995) has pointed out, one of the immigrants’ most clear-cut manifestations of wealth was home renovation. The renovated houses look different from the conventional style, arranged with a ‘modern’ and ‘Western’ design, and this trend goes for Village X as well.

Between the 1980s and the 1990s Village X underwent a construction boom. Those who accumulated wealth by working overseas raced to spend their assets on housing construction. Until then, houses in Village X were built of wood or bricks, but from the late 1980s to the 1990s, four to five story houses made of concrete, with colorful tiles on the exterior walls, were built one by one. The higher the house, the better it was. People also paid great attention to the interior design, which attracted the eyes of visitors and became a point of differentiation. Many of the houses I visited featured huge chandeliers at the entrance hall and a TV surrounded by sofas in the living room.

It is said that the immigrants themselves hardly ever return home to live in the luxurious houses. Instead they were usually occupied by family members left in the village, often the elderly couple or sometimes an elder by themselves, or they were left completely empty. Needless to say, it was not possible for the elder generation to use all the space in the house by themselves, which meant a lot of the space simply remained closed. In many cases, the houses were maintained with outside help such as relatives visiting for regular cleanups or by casual cleaners. This is one of the facts that indicated that people were no longer trying to build a house to fulfil a comfortable and functional ‘modern’ lifestyle, but more as a symbol to show the level of success achieved by working overseas.

However, the trend of home renovation became obsolete by 2000 as more and more people began to choose to migrate to nearby cities. The reasons behind this migration requires further discussions, but people often cited purchasing an apartment in the city as an investment property given the soaring real estate values in the city area or being able to enjoy advanced services such as access to hospitals and schools. Even then, these people usually do not sell their old or renovated houses.

5-3. Donations and contributions to the shrine

Village X has a shrine that village members are deeply devoted to, especially the immigrants. Many pray for their safe journey and the success of their business before departing, and once their prayers are answered, they present offerings to thank the gods, often in the form of plays and movies.

Photo 1 : play for the God

When a play is to be offered, the sponsor invites a theatrical company that specializes in this field and offer performances day and night. Prior to this, it is customary to post a notice, in red paper, on the village bulletin board indicating the details of the play such as who invited the company, when and for what reasons. Being able to enjoy a play is one of the very few entertainments available for the elderly in the village, so when the day arrives, they all flock to the theater.

The quality of theatre companies varies and so does the cost involved in inviting them. For example, if one wishes to invite a company from the provincial theatre school, it would cost about 10,000 yuan, but one may get away with spending 2,000 to 3,000 yuan for a local company. Given that the villagers are aware of the cost and quality of each company from their past experiences as audiences and knowledge gained from those who have actually invited companies in the past, the performance tends to have a significant influence on the appraisal of the host. Generally, it is regarded that the larger the audience the better, so the host often gets creative trying to attract more people to attend the play. Some may even add sentences such as ‘it is going to be really enjoyable so please make sure you come’ to the bulletin board. At the end of the day, when choosing the company, the hosts need to carefully balance the budget and the quality of the company in order to ensure attendance and to save face.

5-4. Contribution to public works projects

In Village X, the‘Public Service Works Foundation’ ( 公益事業基金会 ) was established in 2000. It is an organization whose purpose is to accept donations from overseas immigrants and is managed by the board members of the Elders Society. ‘Public service works’ refers to projects that benefit the whole village such as the construction of public facilities or maintenance of roads. This is the most visible form of contribution to the hometown and such acts are often realized by individuals donating a large amount of funds. Let us look at the case of Mr. R, one of the most prominent overseas immigrants of Village X.

In 2011, the respect-for-the-aged facility opened a new section to commemorate its contributors, in celebration of its tenth anniversary (Photo 2). Here, the photos of the contributors are framed and adorned on the wall, each with the sum of donation stated at the bottom. The photos are laid out in the shape of a pyramid where the positions of the contributors are determined by the amount of donations – the higher the contribution, the higher the contributor’s photo. We can see from here how donation has become a representative tool to elevate one’s reputation in the village, as an individual’s prestige can be clearly recognized through this highly public display.

Photo 2 : Recognition of the contributors through photo display

Список литературы Кто "успешный" мигрант? (Некоторые заметки о социальной дифференциации в эмигрантском сообществе в Китае)

- Chen T. (1939 (1939)), Nanyo Kakyou to Kanton, Fukken shakai (Southern Ocean societies and Guangdong and Fujian societies),Yukitake Sakae (trans.), Mantetsu Toa Keizai Chosakyoku (Mantetsu East Asiatic Economic Investigation Bureau,Tokyo).

- Pan Hongli (2002), Gendai tonan chugoku no kanzoku shakai: Min Nan noson no shukyo soshiki to sono henyo (The religious organizations of Min Nan farming villages and their transformation), Fukyosha, Tokyo.

- Watson J.L.& Rawski E.S(eds), (1994(1988)), Chugoku no shi no girei (The death rituals in China), Heibonsha, Tokyo. (Death ritual in late imperial and modern China. University of California Press)

- Watson J.L., (1995(1975)), Imin to souzoku: Honkon to London no Man shi ichizoku (Emigration and the Chinese lineage: The Man Family in Hong Kong and London), Masahisa Segawa (trans.), Aunsha, Kyoto. (Emigration and the Chinese lineage: the Mans in Hong Kong and London)

- Yanqing (2004) Fujian new immigrant in United States-Case study on illegal immigrant in Fuzhou district in the 1990s. World Ethno-National Studies Vol. 1: 53-59, the institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing.

- Editorial Committee of Zhen Journal of Village X (2010) Journal of Village X. Fujian People’s Publishing House, Fujian.