National identity as driver of tourism development - the study of Norway

Автор: Hegh-Guldberg Olga, Seeler Sabrina

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 42, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The urgent global need to decrease the dependence on natural resource extraction and find solutions for a sustainable future is also reflected in policies prioritized by the Norwegian government. Among others, tourism has been defined as a promising alternative for future economic development. Tourism in Norway has not remained unaffected by the global growth in international tourist arrivals. This growth is often neither geographically nor temporally equally apportioned, which hampers tourism’s transformative power of generating year-round and well-distributed income. Further, tourists are no longer purely driven by hedonic and relaxation needs: they also want to challenge themselves and deeply immerse themselves in foreign nature, culture, and other types of experiences. We argue that better integration of national identity can draw the needs of tourists and hosting communities nearer to each other and, thus, become a driver of tourism development. Based on a comprehensive literature, this conceptual paper explores the core elements of the Norwegian identity, including political and cultural values, national characteristics, interests, and lifestyles, and their integration by the tourism industry. We find that only some of these elements have been used by the industry and have often been commodified for economic gain. We discuss a few examples of how national identity can be translated into unique selling points that could generate sustainable development. This, however, requires strong governance, and coordinated and integrative destination management that involves stakeholders from within tourism and beyond, particularly local communities.

National identity, tourism development, marketing, tourist experience, authenticity, community involvement, norway

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318344

IDR: 148318344 | УДК: 338.48(481)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2021.42.32

Текст научной статьи National identity as driver of tourism development - the study of Norway

This paper aims to explore the role of national identity as a driver of tourism development. Against the background of the current global pandemic, there is a pressing need to restart tourism more sustainably. This is particularly the case as tourism had experienced continuous and partly unsustainable growth in pre-COVID-19 times, with growing tensions between locals and tourists. Within these overtourism tensions, it became increasingly obvious that local communities are not sufficiently integrated in tourism development [1, Høegh-Guldberg O., Seeler S., Eide D.]. However, given that locals are the ambassadors of a destination, their empowerment is of critical importance for a sustainable tourism future. This was also acknowledged by the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that call for holistic approaches to sustainability with bottom-up involvement of all related stakeholders [1, Høegh-Guldberg O. et al.] instead of usually one-sided economic sustainability [2, Harvey D.], [3, Temesgen A., Storsletten V., Jakobsen O.]. It

also means that tourism marketing needs to be redefined and go beyond the aim to attract as many tourists as possible through partly unrealistic and romanticized, often outdated, images.

Aside from fragmentation and insufficient integration of tourism offerings with other services, tourism activities are often partially or entirely detached from the lives, values, and beliefs of local communities and the identity of a place. It is, however, the local communities that portray the development of that particular destination, explaining its history, culture, and heritage. At the same time, tourist experiences that are authentic, and combine learning, entertaining, and improving social gathering in the process of consumer immersion [4, Hansen A.H., Mossberg L. ]; [5, Sundbo J., Sørensen F., Fuglsang L.] are often the reason to visit destinations and are increasingly expected by contemporary tourists. Although the consequences of COVID-19 illustrate the extreme economic vulnerability of countries and regions that significantly rely on tourism, traveling and recreation are not expected to diminish but rather acquire new forms in the long term. We assume that when used strategically for holistic and sustainable destination development, identity can be a source of pride and various benefits for the hosting communities.

Theoretically, the paper distinguishes itself from the more traditional perspective to tourism development and marketing [6, Pike S., Page S.J.], [7, Viken A., Granås B.] by supplementing it with social identity theory [8, Tajfel H.] and experiences as the main tourism product [9, Pedersen A.-J.], [10, Pine B.J., Gilmore J.H.]. We depart from the contemporary tourism marketing research where commercially developed images affect consumer behavior, and move toward a social psychological view of images which is compatible with and ingrained in the identity of communities. Practically, the paper suggests that identities possess large potential to contribute to tourism development, which has only fragmentarily been addressed by the Norwegian tourism industry.

This introduction section of the paper is followed by the theoretical section that first discusses the status quo of using identity in tourism development from the traditional perspective and then looks more closely into the building blocks and core elements of the national identity from the sociological and social psychological perspectives. The central concept discussed by the paper is national identity ; however, given both the chosen perspective of understanding national identity as grown out of a country’s regions and the importance of regional/destination development for the tourism industry, the notion of regional identity is naturally touched upon. The theoretical section closes by presenting initial ideas for how identity can be integrated into tourist experiences. The research methods and context of Norway are then presented. Following this, the findings section presents the development and the core elements of the Norwegian national identity and their use by the tourism industry. Later, the discussion section analyzes the results and discusses them against existing literature, and suggests unused potential in the use of national identity for tourism development and implications, before the concluding remarks.

The role of identity in tourism development and promotion

A touristic image is often based on manifestations and stereotypes reinforced by tourism producers [11, Freire J.R.]. France, for instance, is associated with the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, the French Riviera, and wine, or Germany with Bavaria, Schloss Neuschwanstein, Oktoberfest, and sausages. How true are these stereotypes that travelers have about other nations and do they describe the current generation as much as previous ones? Do these stereotypes reflect the whole nation or only particular regions and specific events, such as the example from Germany whose international image and reputation as a tourism destination is largely driven by Southern Germany landscapes and attributes? It also raises the question of how locals feel about these stereotypes and whether they want to be seen and spoken about in such ways.

Given the unique and salient features of the tourism product, such as intangibility and perishability, while acknowledging that tourism can be a way to learn about other cultures and improve mutual understanding and respect, marketing and branding remains decisive for any tourism business’s success. According to White L. [12, p. 12], an image of a nation brand is “based upon people’s previous knowledge, beliefs and experiences, or on the stereotypes of its people and the social, political and economic conditions.” It is namely the consumers that have until recently primarily been in the focus of the tourism research, leaving the actual process of image development by destination stakeholders less understood [13, Kong W.H., du Cros H., Ong C.E.]. The challenge lies in constructing a destination image that attracts visitors, while at the same time ensuring that residual meaning remains and regional identities are not overpowered by emergent and hegemonic meaning. Jeuring J.H.D. [14, p. 66] notes the simultaneous processes of homogenization and differentiation, and describes the latter as a “rat-race with other destinations, attempting to create a ‘competitive identity’.” However, Anholt S. [15] argues that national images cannot be constructed but earned, and questions whether marketing communication can shift deeply rooted phenomena such as a national brand.

Using the example of the Dutch province of Fryslân, Jeuring J.H.D. [14] finds that tourism marketing portrayed Frisian identity as static, predefined, and thus materialized. This materialization of regional identity in the past was driven by dominating neoliberal growth strategies and “boosterist traditions of mass marketing” [16, Timothy D.J., Ron A.S., p. 276]. In this vein, Font X. and McCabe S. [17] describe tourism marketing as being exploitive and driving hedonistic consumerism, and Jeuring J.H.D. [14, p. 65] argues that destination identities “may be politically charged […] and attributed meaning may be far from neutral.” Although tourism can contribute to cultural and natural preservation, community pride, and stakeholder unification, the dominant regional identity is often “materialized through hegemonic discourse such as the association of regional identity with tourism and regional development” [18, Paasi A., p. 1209]. In other words, it is a communicated identity, i.e., a desired public image communicated to environments to promote their own interests [19, Cornelissen J.P., Haslam S.A., Balmer J.M.]. The communicated identity should, however, be as genuine and authentic as it can, because images are said to be earned since “neither a country nor a region [,] really controls its image, especially in today’s transparent, fast-moving and increasingly digital communication landscape” [20, Magnus J., pp. 197–198].

Paasi A. [18, p. 1207] argues that regional identities are “vital in planning and marketing as a means of mobilizing human resources and strengthening regional competitiveness.” Similarly, Timothy D.J. and Ron A.S. [16, p. 277] acknowledge the importance of local empowerment and note that “destinations that are psychologically empowered rejoice in their cultural traditions and happily share them with tourists.” Jeuring J.H.D. [14] proposes that residents are indispensable in destination branding and marketing, as tourism destinations are socially constructed and identities formed through discursive practice that goes beyond the tourism realm. Scholars also note that top-down approaches to tourism branding and marketing prevail and responsible parties, such as destination marketing organizations (DMOs) and governments, fail to embed local stakeholders more strategically [14, Jeuring J.H.D.], [21, Mihalic T.].

The sustained growth of tourism in the past decades and prior to COVID-19 demonstrates the centrality of economic goals and profit maximization over social and environmental concerns and thus a weak form of sustainability [22, McCool S.F.]. As tipping points have been reached in numerous places and tendencies of overtourism evolved, local communities’ goodwill diminished and anti-tourism attitudes increasingly emerged [23, Papathanassis A.]. Not only do locals feel that their own identity and culture are vanishing, but they also realize that their cultural and natural heritage is capitalized on for tourism purposes and economic growth aims. More decentralized forms of destination planning and development are called upon that equally acknowledge economic, environmental, and social sustainability [24, Saarinen J.]. To integrate identity more authentically, respectfully, and sustainably in tourism development and marketing, a better understanding of these deeply ingrained and rooted concepts is required.

National identity and its core elements

National identity and spatial boundaries are usually understood as instrumental in the process of nation building or as interstitial zones in the process of globalization and transnationalization [25, Lamont M., Molnár V.]. In this paper, we adopt a broader perspective and take the development and status quo of identity in mind. In that sense, we depart from an understanding of identities as a matter of “being” to a matter of “becoming,” transcending time and space, and belonging just as much to the future as to the past and present [26, Govers R.]. We understand identity confined to national boundaries as grown out of a country’s regions, which in its turn is based on the overall concept of social identity . Thus, the focus shifts from geopolitical changes and primarily top-down approaches to humanistic aspects of identity. Human identity is defined by a set of beliefs, values, and expressions and is, thus, rather a fuzzy concept, especially when moving from personal to social identity [19, Cornelissen J.P. et al.] . A central element of personal identity that has direct implications for understanding identity within tourism destinations is place identity described as belonging to a certain place, and interactions with the physical environment [27,

Hernández B. et al.]. Otherwise, it is the social identity defined as “the individual’s knowledge that he/she belongs to certain social groups together with some emotional and value significance to him/her of the group membership” [28, Tajfel H., p. 31] that is central to understanding communities and their identities. Collective identity complements the social identity based on shared belonging within one’s own group, by recognizing the differentiation of the group by outsiders [29, Jenkins R.].

Thus, social identity is produced and reproduced in relation to other social units and is said to be found at individual, group, organization, and other levels [19, Cornelissen et al.]. Eriksen T.H. and Neumann I.B. [30] expand knowledge on identity and add two characteristics to relationality: identity is in constant change due to dynamics in external relationships, and not all relationships form identity equally. Although abstracted from a specific place (compared to place identity), regional and national identities , as a sense of belonging to a region and a nation, can be understood in relation to and by differences from other regions within a country and other nation states. Further, not only is identity formed and reformed at intrapersonal and interpersonal levels, but it also links, informs, and shapes the different levels [31, Albert S.].

On the national level, identity is often mistaken with belonging to a certain culture. Eriksen T.H. and Neumann I.B. [30] distinguish the two as follows: while national culture is about common meaning, national identity is about group formation and social boundaries. “Culture varies along a continuum and is devoid of sharp boundaries, while social identity is discontinuous with boundaries guarded zealously” [30, Eriksen T.H. and Neumann I.B., p. 414]. At the same time, culture and identity are interwoven: a national culture as a set of common symbols (including literate and artistic expression, symbolic achievements, dominating values, beliefs, and way of life) serves as a reference for both orientation and identification, and for the mobilization of collective actions [32, Skirbekk S.N.]. National culture is, however, only one of the building blocks in national identity formation. Seemingly, identity research overall has prioritized the process of identity development over what actually constitutes an identity [33, Galliher R.V., McLean K.C., Syed M.]. Nevertheless, the constitutive elements of national identity and their combinations can be derived from the dominant views of national identity, including essentialist, constructivist, and civic theories as shown in Table 1, and hybrid understandings of the three views [34, Verdugo R.R., Milne A.].

Table 1

Dominant views of national identity

|

Dominant views of national identity |

Central to understanding |

Core elements |

|

Essentialist /primordialist |

National identity being fixed |

Culture, history, language, ancestry, and blood |

|

Constructivist/postmodernist [imagined vs invented for political reasons] |

Dominant groups create, manipulate, and dismantle identities for their specific gains |

Print languages, symbols, rituals, and other ceremonials, politics, use of power |

|

Civic identity |

Membership in a geopolitical entity is unfettered by ethnicity or culture |

Shared values about rights and the legitimacy of state institutions to govern |

These views are not homogeneous. Some scholars argue that national identity is a combination of natural processes and conscious manipulations found on the scale between essentialist and constructivist views, depending on the weight assigned to it by social systems [35, Smith A.D.]. Postmodernists argue that the constructivist view underestimates the role of power, “and that such an error leads them to incorrectly suggest that influence and agency are ‘a multidirectional’” [34, Verdugo R.R., Milne A., p. 5]. Both arguments reflect the idea that the formation of national identities is dominated by top-down approaches, leaving little space for bottom-up formation processes. Following the debate on the constitutive elements of national identity, Piątek K. [36] suggests the following: common culture, common national interests, national characteristics, community of common history, national solidarity, and political values. Although the elements of national identity can be a subject of dispute, history is a central element [30, Eriksen T.H. and Neumann I.B.] and believed to have the ability to “guide and cement national identities” [37, Gammon S., p. 1]. National history not only describes national developments in the past and present, but also sets an outlook for a nation’s future, i.e., a nation’s potential responses and actions based on historical values [12, White L.]. The individual elements as well as the identity as a whole are relational [18, Paasi A.]. Thus, differences in regional identities can be related to different dialects and even languages, or differences in landscape and way of living within the same country. Such regional differences can be related to a country’s size and disposition. These elements hold potential for sustainable tourism development and can help regions, generalized at the central level, to stand out [38, Lundberg A.K. et al.].

To meet the aims of the paper, we explore the following research question: How are the core elements of national identity being used by the Norwegian tourism industry?

Systematic development and collaborative innovation of authentic, sustainable tourist experiences by the tourism industry can be a way to integrate genuine identity into tourism. Following the experience logic [39, Pine B.J., Gilmore J.H.], the primary product of tourism is an experience that is not only immaterial, interactive, produced, and consumed simultaneously, but is also extraordinary, implies personal involvement, and is memorable and meaningful [40, Mossberg L.]. Successful tourism experiences can be designed in a way to meet tourists’ need for immersing themselves into an experience without compromising local sustainability [41, Breiby M.A. et al.]. Pine B.J. and Gilmore J.H. [39] introduce the experience realms from passive to active participation and from absorbing an experience toward immersing oneself in it. Tarssanen S. and Kylänen M. [42] discusses how an experience can be created in such a way that a tourist being motivated to purchase an experience transcends toward undergoing personal transformation through physical [senses], intellectual [learning], and emotional levels during the experience. This can be done through six main characteristics of an experience: [1] contrast, how an experience is different from the daily life of a tourist; [2] individuality, how unique an experience is and how it appeals to the tourist; [3] authenticity, how an experience’s image matches the experience product; [4] story, how clear the meaningful in an experience emerges; [5] multisensory experience, how and which senses are involved; and [6] interac- tional, how interactional an experience is [9, Pedersen A.-J.]. These experience characteristics are both further developed, e.g., tourist interactions with the experience room, other tourists, and personnel, as well as physical objects and self-reflection, and supplemented by other tools, e.g., a dramaturgy curve describing intensity and flow in an experience product [43, Eide D., Mossberg L.].

Methods

This conceptual paper builds on a comprehensive literature review and uses Norway as the research context. Given the fragmented nature of research on Norwegian identity, conceptual obscurity, and complexity of the research, a systematic database search seemed less suitable and beneficial, and instead a snowball sampling technique was adopted. A snowballing method is defined as “using the reference list of a paper or the citations to the paper to identify additional papers” and "looking at where papers are actually referenced and where papers are cited” to secure backward and forward snowballing [44, Wohlin C., p. 1]. We used Scopus, Google Scholar, and a broader Google search for the comprehensive literature review. We used Google Scholar for scholarly articles and materials that were missing in the Scopus database [including reports of Norwegian and international organizations], as well as a broader Google search for media articles and statistical data. These complementary search methods can be fruitful in providing credible results for such a multifaceted research topic discussed in the Norwegian, Danish, English, and Swedish languages. We base our analysis on more than one hundred publications that we sourced through our multi-staged database searches. This approach allowed us to identify the relationships among the constructs in the context of the Norwegian tourism industry. The literature was systematized according to the core elements of national identity from the three dominant views [see Table 1] and deductive exploration in relation to destination development and marketing approaches in the context of the Norwegian tourism industry.

National and regional tourism development in Norway as the research context

In order to elaborate on how Norwegian identity can a be a driver of tourism development in Norway and its regions, an understanding of the status quo and development of Norwegian’s tourism industry is needed.

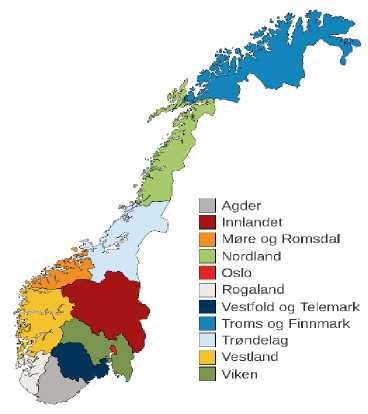

Norway is a north-western Scandinavian country with fascinating nature including deep fjords, glaciers, mountains, rugged coastline, islands, and sea. The current population of Norway is about 5.4 million people 1 with the average density of 15 people per km² 2. Norway consists of eleven counties (see Figure 1) with the highest concentration in Southern (Oslo and Viken, 1.9 million) and Western Norway (1.4 million) 3.

The most densely populated counties in Norway are also most visited by holidaymakers 4, as shown in Table 2. According to the 2019 tourism industry survey [ibid.], this can be explained by the trend of tourists often coming to Norway by air to the country’s largest hub in Oslo, as well as natural beauty of Western Norway which often stars in national promotional campaigns.

Fig. 1. Norway's counties.

Table 2

|

Regions |

Volume of holiday tourism [in millions of guest-nights] |

Total consumption [billions NOK] |

||

|

Norwegian holidaymakers |

Foreign holidaymakers |

Norwegian holidaymakers |

Foreign holidaymakers |

|

|

Oslo & Akerhus |

7.5 |

3.6 |

9.7 |

4.3 |

|

Eastern Norway |

22.7 |

2.2 |

21.2 |

2.4 |

|

Northern Norway |

16.2 |

2.4 |

14.2 |

2.6 |

|

Trøndelag |

7.5 |

3.6 |

8.3 |

1.7 |

|

Fjord Norway |

15.9 |

3.8 |

10.5 |

4.3 |

|

Southern Norway |

5.5 |

0.8 |

10.3 |

0.7 |

Volume of holiday tourism and consumption per region in 2018 5

According to Innovation Norway, “… nature is the main reason why most people want to travel here [Norway] on vacation.”6 Tourism demand for nature-based tourist experiences in other parts of the country, for instance in Northern Norway where tourism is one of the top three strategically developed industries [45, Kildal Iversen E., Løge T., Helseth A.], has also grown in the past years. With its steep mountains and dramatic landscape, Northern Norway is of critical importance for Norwegian national identity [46, Andersen L.P. et al.]. The region attracts tourists by its natural beauty including the midnight sun, the Northern Lights, dramatic landscapes, and craggy mountains, etc. [47, Andersen L.P., Lindberg F., Östberg J.].

In 2019, tourism contributed 8% to Norwegian’s total GDP and generated more than 309,000 jobs 7. However, the growing number of visitors and strong focus on nature-based experiences may lead to disbalances and unsustainable tourism [48, Heslinga J.H., Hartman S., Wielenga B.]. The importance of developing other types of tourist experiences, for instance cultural, and meeting tourist demand for holistic experiences has recently reached the Norwegian political agenda 8, 9.

Findings: The role of national identity in tourism development in Norway

“The nation exists in the everyday lives, and the minds, hearts and imaginations of people, who live within a national space” [49, Erdal M. et al., p. 3]

Community of common history . Research discussion on Norwegian identity remained scant until the 1980s when the discussion of nation building in contrast to Danish and Swedish legacies evolved [30, Eriksen T.H. and Neumann I.B.]. One example is a discussion of the formation of national identities in Norway and Denmark before and after 1814 [50, Glenthøj R.], the year when Norway adopted its own constitution and chose its king in the few months between being ruled by Denmark and forced into a union with Sweden. It was namely joint governance rather than nations that formed culture and identities, with Danes and Norwegians seen more as ethnic groups before nationalistic movements in the early 19th century [51, Eisenträger S.]. Strong backlashes among the Norwegian population as a reaction to a number of political and economic decisions upon the “divorce” [50, Glenthøj R.] stimulated the formation of a Norwegian identity as resentment against everything Danish. Although without particular linkage to identity, Norway started talking about its own language and writing its own history, when it had previously been subordinate to Denmark for over four centuries. The union with Sweden started in conditions of deep economic crisis in Norway, with the gradually growing role of parliament and nationalistic expressions ceremonially celebrated each year on May 17th ever since [52, Mardal M.A.]. While May

17th has become an important marker for Norwegian national identity and has also been used in tourism promotions, it often seems to lose touch with history.

Fig. 2. Present-day celebration of May 17th in Oslo

Political values. Class contradictions in the mid-19th century were reflected in opposition in the parliament structure. Following an agriculture crisis and the formation of peasant associations in the 1860s, a left-wing block was formed [52, Mardal M.A]. Power struggles and dissent between parliament, government, and the king ended in the national court in the 1890s and paved the way for parliamentarism and a government based on a majority resolution [53, Kaartvedt A.]. The dispute about the Swedish Union and setting up a union committee gained in importance. Disagreement on the number of Norwegian representatives in the Foreign Ministry, unofficial war threats from Sweden, and dissolution of the union committee led to strong resentment in Norway and dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905 [52, Mardal M.A]. The dissolution was not least due to an emerging national identity and a will to establish its own foreign missions and thus have equal union position. Norway proceeded by choosing a Danish prince as its own king, the choice reinforced by political advantages 11. Modern Norway is often characterized by the Nordic model of politics which is built on the “conditions of statehood and representative government” [54, Østerud Ø., p. 705]. It is a country with the strong role of regions reflected, for example, in the Norwegian European Union (EU) debate and voting in 1994, where the majority of the Norwegian population voted against joining the EU, as it would mean greater centralization of the country [30, Eriksen T.H. and Neumann I.B.]. This example illustrates how national identity can reinforce and reproduce its separate elements in the course of commercial and political matters. Relational perspectives and community identity are central in the Nordic context where national and regional identities are shaped by civic order and collective welfare [55, Cassinger C., Lucarelli A., Gyimóthy S.]. Although argued to be under transformation, the Nordic model is a great political example for other countries. Particularly international visitors are drawn by the Nordic model, and the idea of Norway’s independence and neutrality.

National characteristics. Besides its profound role in forming Norwegian identity and pride in the nation’s independency, the common history of Norway and Sweden, and especially Norway and Denmark, remains influential. Thus, it is hard to deny that the Norwegian population has preserved certain Nordic traits in their DNA. Metaphorically calling the year 1814 a divorce, Glenthøj R. [50, p. 27] emphasizes that there are strong feelings at stake when two countries split. For over 400 years, Denmark and Norway had been connected through families and culture. “Ibsen, Hamsun and Bjørnson published their books in Copenhagen, and Danish travelers often described Christiania as a ‘Danish’ city, most of all reminiscent of Christianshavn” [50, Glenthøj R., p. 27]. Throughout the years, the Nordic region has earned its genuine image including the five following strengths: (1) compassion, tolerance, and conviction about the equal value of all people; (2) openness and a belief in everyone’s right to express their opinion; (3) trust in each other and also, because of proximity to power, trust in leaders in society; (4) new ways of thinking, focusing on creativity and innovations; (5) sustainable management of environment and development of natural resources [20, Magnus J.]. At the same time, understanding that all Nordic countries have the same cultural values can be misleading and is not necessarily true, as each nation has its unique cultural practices and interpretations of the shared values. Warner-Søderholm G. [56, p. 1] notes that “Norwegian cultural practices within a Nordic context are seen to be higher gender egalitarianism” compared to other Nordic countries. While Denmark is most often associated with being the leading Nordic country with low power distance, the latter also characterizes Norway: “Being independent, hierarchy for convenience only, equal rights, superiors accessible, coaching leader, management facilitates and empowers” 12. Hofstede Insights 13 describes Norwegians as individualists and the world’s second most feminist society: the former implies the importance of personal opinions explicitly communicated, while the latter implies an appreciation of consensus and sympathy for others, social solidarity, and taking care of the environment. The country is considered a leader in green and blue sectors, with the idea of being a sustainability pioneer transported through branding and positioning 14. This is also reflected in tourism marketing where images of a green and sustainable destination with environmentally friendly offers are central. Innovation Norway 15 frames this as “greenspiration” and the overall slogan “powered by nature.” However, green travel in tourism marketing goes beyond images of the natural landscape, such as deep fjords and mountains: it also depicts aspects of Norwegian identity and cultural values. On the Visit Norway website 16 green travel is communicated through pureness portrayed in natural water sources and green surroundings: through human nakedness, with the strong and muscular male body which reminds one of the strength of Vikings but also Norwegian’s general interest in physical activities; and through adaptiveness, roughness, and resistance, reflected by moss and grass that defy the rocks, and water finding its ways down the rough rock walls.

Norwegians do not like direct confrontation, which may be experienced by outsiders as being coldhearted. According to Norwegian youth, equality, democracy, and freedom are fundamentals for Norwegianness [49, Erdal M. et al.]. In the conditions of growing immigration, the same study shows that Norwegianness can also be experienced as a matter of first impressions, i.e., skin color, name, and clothing, although this impression is shared primarily by the informants with immigrant background. Erdal M. et al. [49, p. 27] find that national identity has more recently become “central to public debates on immigration and integration, and managing societal diversity has become highly politicized, with concerns about security and migration often conflated.” Similar debates arose earlier in the context of the Sami population residing primarily in the northern part of the country, such as the Finnmark Plateau. The Sami population experienced oppression of their culture and native language especially in the years of Norwegization and assimilation. With the growing interest in authenticity, immersion, and understanding other cultures and indigenous people, the Norwegian tourism industry has more recently understood the potential of their unique Sami culture for tourism development, and several initiatives have been formulated and product innovations called upon.

Economic dimension: reinterpreting nature. The mid-19th century is called “a new society” in Norwegian history, as that was the time when new business, mechanization, and emigration gradually emerged. After modest development of Norwegian industry until the 1870s, the country experienced a strong growth period in particular with reference to timber, iron, and textile industries [52, Mardal M.A.]. After the economic depression in the 1880s, Norway experienced a new economic leap toward being an industrial society, including the transition to steam shipping and the development of a full-cycle cellulose industry [52, Mardal M.A.]. With the exception of periods of war, the years between 1900 and 1950 are characterized by a steady increase in production volume. This is also reflected in the quadrupling of the gross domestic product calculated at fixed prices of that period 17. Thus, even before the oil, Norway had been “a relatively rich, democratic and industrial nation” [54, Østerud Ø., p. 708]. However, the economic importance of oil is mirrored in the GDP growth per capita from a relatively low level in 1971 to one of four top positions among OECD countries in the past decade 18. The key industries for Norwegian economy before, during, and after the discovery of rich oil and gas deposits on the Norwegian continental shelf are also illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3

Key industries in Norwegian GDP, in % 19.

|

Main industries |

1950 |

1980 |

2000 |

|

Agriculture, forestry and fishing |

23.7 |

16.7 |

13.5 |

|

Oil operations |

15.5 |

25.8 |

17 Økonomisk utsyn 1900-1950. Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1955. URL:

(accessed 05 October 2020).

(accessed 20 August 2020).

19 Source: Statistics Norway [2005].

|

Industry, mining, power supply |

27.0 |

18.9 |

12.9 |

|

Construction |

7.1 |

5.2 |

4.1 |

|

Transport and communication |

15.4 |

9.4 |

7.3 |

|

Other services |

37.0 |

46.9 |

47.8 |

Norwegian identity is commonly framed by the country’s rich natural resources and international understanding of being an oil nation. And while the identity as a “rich, well-organized, egalitarian and democratic” [30, Eriksen T.H. and Neumann I.B., p. 431] nation holds, the question arises whether such an identity should be sustained by similar means, i.e., the oil legacy, or whether a change is needed, particularly as this national image has already been threatened by discussions around climate change and other unpredicted global threats such as COVID-19. Undoubtedly, the petroleum industry has played an important role in the Norwegian economy and welfare in the past decades 20. In the recent COVID-19 pandemic, it also proves to serve as a safety net to cover the deficit in the state budget in recovery during and after the crisis 21.

Although the general perception of Norway as a “cold and wet” country with “consistently poor growth conditions” [57, Eika T., Olsen Ø., p. 32] before oil has changed, traditional industries of agriculture and forestry have been diminishing ever since. At the same time, the country preserved “the strength of the rural districts and the periphery” [54, Østerud Ø., p. 705] with fish and other seafood suggested as being the new oil [58, Røed H.]. As an important resource base for the population along the coast, fishing is still one of Norway's largest export industries. The long-term expediency of petroleum activities has been debated in South and North Norway, for instance the exploration of oil in the areas around Lofoten, Vesterålen, and Senja in the past years [59, Stam-nes E.]. In his book “An Ocean of Opportunities”, Røed H. [58, p. 1] argues that the oil era is approaching its end while Norway stands with a lottery ticket in its hands: “Norway’s biggest values are not as many perhaps believe mountains and valleys, but fjords, coastline and ocean”. He further emphasizes the necessity of new and old industries, local produce, and sustainable innovation, which are not least enhancing strategies for other alternative industries, such as tourism.

Meanwhile, tourism has already capitalized on the beauty of Norwegian nature, reflected in the tourism demand largely driven by Norway’s natural capital and landscape [60, Øian H. et al.]. As summarized by Andersen L.P. et al. [47, p. 14], “regional branding strategies rely heavily on a rhetoric that cultivates myths, images and ideas of the geographical landscape as terroir”. In the case of Norway this means romantic images of deep fjords, long coastlines, and dramatic landscapes with craggy mountain peaks, the Northern Lights, and the midnight sun. The increase in visitors has also added pressure on certain destinations and their resources, and has raised questions related to visitor safety. While measures were implemented, such as stairs at Reinebringen on Lofoten, these often neither reduce the pressure as more tourists are attracted by improved infrastructure which brings new challenges (e.g., parking), nor are they appreciated by locals as they feel that these measures are interfering with their lives and ideas of open space, freedom, and undisrupted nature, and thus their regional identities [47, Andersen et al.], [61, Hagen L.F., Kristoffersen K.J.]. These also evoke perceptions that public access rights to nature are institutionalized and capitalized on [60, Øian H. et al.].

Common national interests and lifestyle. The most common national interests among Norwegians include playing music (9.4%), travel (8.7%), cooking (8%), reading (7.8%), camping (7.5%), health and fitness (6%), interior decorating/renovating (5.3%), technology/computer (5.2%), and arts and crafts (5.1%) 22. The majority of Norwegians agree that the country’s rich nature unites them in their interests in hiking, skiing, and simply being in nature in all seasons and any type of weather. Norwegians are famous for cross-country skiing, given regular training [also during the non-winter season on roller skis], infrastructure, and respective climate. “Allemannsretten” [right to roam] and the idea of “Friluftsliv” [outdoor recreation lifestyles] are deeply ingrained in the Norwegian identity [46, Andersen et al.], and the ideal of traditional Norwegian outdoor recreation revolves around wilderness purism with minimal resources and infrastructure [62, Martin D.M., Lindberg F., Fitchett J.]; [63, Vistad O.I., Vorkinn M.]. From an early age children are exposed to many hours outside mastering nature, and reviving fairytales and mythical creatures, e.g., trolls.

Norway, particularly the High North, depicts a challenge in itself, and Nordic people share a strong national and regional identity of adaptiveness, resistance, resilience, and traditions. With a recent marketing campaign “We have survived nature for ages” 23 Visit Norway sets an example of how these characteristics of national identity can be translated into unique selling points that can generate sustainable development. The promotional video is narrated by a male Norwegian depicting a “typical Viking style.” He shares a story of survival and self-restraint during the darkest times of the year, which is also visually transported by using gray shades and imagery in the video. The power of nature and the centrality of water are not only visually demonstrated but also described as a “constant battle between the West Coast and the North Sea.” At the same time, the narrator highlights the adaptiveness and resistance of Norwegians. He clearly addresses the challenges associated with the place yet turns them into strength, with statements such as “These places never cease to surprise” or “We don’t live here because it is convenient or comfortable — we explore these narrow fjords to challenge ourselves.” This promotional video stands in stark contrast to other campaigns that focus on iconic landmarks, such as the Geiranger Fjord or Lofoten Archipelago, as it focuses on Norwegians, their lifestyles, and attitudes toward the long winter and dark months of the year. It also responds to the assumption circulating that people in the North suffer from depression in the dark months, as it highlights their interpretation of it as being a challenging and demanding yet exciting time.

Another example of successful authentic regional development and promotion is Bodø’s entitlement as European Cultural Capital 2024. Bodø has set another example of using the challenging living and climate conditions to demonstrate the uniqueness of the Arctic location and the adaptiveness and resilience of Northern Norwegians. Thereby, the application committee was not shy in articulating that the region understands that the cultural system that has evolved as a response to the challenging environment might seem inhospitable and forbidding to some. However, instead of making this a weakness, it became the strength of the application as they understand that the Cultural Capital “provides an opportunity to show that there is much more to our part of Northern Norway than the stereotypical Arctic image which most Europeans have” 24. This bravery and honesty became a success. In their application, they clearly highlighted the extreme changes of light and peculiarities of the season which define the way of life and contribute to national and regional identity; they are described as spring optimism, midsummer madness, autumn storms, and arctic light.

Many Norwegians have their own cabins and holiday houses in picturesque little villages close to their place of residence, in other parts of the country, or elsewhere in the Nordics [increasingly also in Southern Europe], to spend most of their non-working time close to nature. Another trait Norwegians share with their Nordic family is “kos,” implying spending time with friends and family, lighting candles in dark winter days, eating a good meal, or being in a cabin preferably “in the middle of the mountains with no electricity or running water” 25. Norway is a spacious country with a rather sparse population, with personal space being important for its inhabitants. The long-standing tradition of second homes and privately owned cabins in the mountains and forests as well as fishing cabins is also being increasingly transformed to meet the growing demand for authentic and unique accommodation types and off-the-beaten-track travel [64, Seeler S., Schänzel H.A., Lück M.]. In comparison to the contemporary utopian view of Nordicness, Andersen L.P. et al. [47] address the evolving conflicts between traditional and modern life. For instance, micro-cabin concepts such as the Arctic Hideaway that markets itself as “simplicity at its finest” 26 or Manshausen 27, combine modern and traditional lifestyles. These micro-cabin concepts have gained international attention 28, given the growing trends toward more unique and authentic accommodation styles and the continuous growth of glamping as a more luxurious and glamorous form of camping [65, Brochado A., Pereira C.]. Glamping in general gained in importance in Norway with concepts like arctic domes, yurts, hanging cocoons, glass igloos and ice hotels, or Lavvo tents which are traditional in the Sami way of life. Overall, simplicity, functionality, cleanliness, and closeness to nature as well as traditions and the general idea of coziness remain distinctive in Nordic architecture and design, and are demanded by tourists and consumers of Scandinavian products in general [e.g., Ikea, Noma] [47, Andersen L.P. et al.], [66, Pamment J.]. While a segment of the tourist market appreciates infrastructure developments, such as the Reinebringen stairs as they provide access to those who were previously discouraged from experiencing Reinebringen, or the commodification of traditional fishing cabins as they prefer a form of luxurious simplicity, other segments of the tourist market aim for deep immersion into foreign cultures and want to challenge their own status quo.

Common culture and national celebrations. History and nature are fundamental components in national identity and are expressed through multiple cultural elements such as visual arts, literature, and spatial planning [67, Gullestad M.]. Thus, certain historical periods, for instance Viking history as one of the most famous and influential periods in Norwegian history, often become a plot for films, books, cartoons, and toys, and find their expression in thematic events, games, and festivals [68, Løkka N.]. Both past and modern cultural expressions are influenced by the Viking legacy as a part of Norwegian identity and self-understanding: “We refer to ourselves as Vikings when we swim in cold water, when children are encouraged to be brave, when we walk without wool underwear in cold weather or when we win in sports” [68, Løkka N., p. 51]. The big names of Fridtjof Nansen and Thor Heyerdahl complement this picture of being Norwegian. Inspired by Norwegian nature and landscape, the works of Edvard Munch, Henrik Ibsen, Edvard Grieg, and Gustav Vigeland, to name a few, represent well-known Norwegian cultural expression. However, culture is much more than cultural expression, and identity is also reflected through values, beliefs, and way of life. In this vein, Johansen A. [69, p. 100] proposes that “Norwegians are down-to-earth, trustworthy, side-by-side in one version, they are romantic dreamers of the type Peer Gynt and Henrik Wergeland, or they are adventurers with a wanderlust, such as the vikings, Nansen and Heyerdahl in other versions.” Here the author refers to both cultural and historical expressions as well as values and beliefs.

Timothy D.J. and Ron A.S. [14, p. 278] highlight the importance of national cuisine in identity building and state that cuisine is “one of the most salient manifestations of traditional culture, and an important element of intangible heritage”. They further note that “cuisine and foodways are crucial building blocks of regional or national identity” [14, Timothy D.J., Ron A.S., p. 278]. Place is another salient element of cuisine and thus identity. Because of the peculiarities of place, from both natural and cultural perspectives, gastronomies developed in different ways in different places and continue to this day to be one of the most important identifiers of uniqueness of place and sense of place [14, Timothy D.J., Ron A.S.]. Alongside the rich fish diet, smoked whale meat is often served as finger food at different events and arrangements in Norway. Moose meat served with jam often appears as a delicacy on the menu for foreigners in Norway. Furthermore, the Eastern part of Norway is famous for its brown cheese, often eaten on waffles with strawberry jam. And of course, given its closeness to nature, travel food including flatbread and other types of bread with various types of filling [cheese and meat slices or similar] is popular among Norwegians.

National celebrations are endowed with national attributes and traditions, such as wearing national clothes (bunad) for May 17th, or watching crime movies and eating marzipan during Easter holidays. These celebrations, with May 17th being the strongest example, are tailored for specific (international) audiences and commodified for tourism purposes. This is not unique to the Norwegian tourism industry yet is risky as it is a threat to authenticity [70, Sanin J.]. Given that contemporary tourists are increasingly interested in national culture and traditions while at the same time aiming for entertainment and enjoyment, commodification also takes place with reference to national celebrations, cultural attractions (e.g., Viking museums or Sami experiences), food-related experiences (e.g., cod and skrei fishing), or other national interests and traditions (e.g., wild reindeer hunting, dog-sledging). As the national DMO, Innovation Norway promotes Norway’s national day, May 17th, as a “party like no other,” compares it with the Brazilian carnival or the Irish Saint Patrick’s Day, and admits that the celebration is somehow nationalistic and depicts patriotism 29. This examples illustrates the seamlessness of national and commercial nationalism [71, Seeler S.] and draws into question whether a celebration for national pride and feeling of belongingness to the Norwegian community should be “sold” and “promoted” as such.

Another commodification of national identity in tourism is through souvenirs. Alongside food souvenirs such as brown cheese, salmon, reindeer meat, and aquavit, traditional costumes and iconic knitwear feature Nordic designs, and Norwegian souvenir shops are packed with trolls as symbols of Scandinavian folklore, Viking jewelry, and Viking drinking bowls that are touristy, tawdry, and less authentic. While some tourists value the symbolic meaning behind souvenirs, others are less concerned about the authenticity of souvenirs [72, Fu Y. et al.]. This raises the question about to what degree the commodification of souvenirs risks the loss of common culture and identity and rather fosters stereotypical assumptions about a place through crude primitive art and kitsch [73, Hume D.L.].

In order to explore the use of national identity in tourism development in Norway, the findings section has provided an overview of the political and economic development of the country that has influenced the formation of the national identity. Given its inherent two-sidedness of being an independent country, yet bound to Denmark and Sweden by common history, it is the identity “as the matter of becoming” [26, Govers R.] that needs to come into the light. This implies not only calling up the central characteristics of Norwegian society, such as gender egalitarianism, low power distance, individualism, and solidarity, but also how these are contrasted with and influenced by the ongoing developments of growing immigration and recognition of the indigenous people. Naturebased recreation and outdoor life, so important for many Norwegians and cultivating their adap- tiveness and resilience, has to a growing degree been used by the tourism industry capitalizing on the country’s natural resources. While this illustrates the integration of the identity elements into tourism, it may also conceal the negative effects. Firstly, it is the risk of misinterpretation and contradiction in nature-based experiences presumably developed to meet existing demand, as in the example of glamping. Namely, experience authenticity is often challenged as commodification changes the actual meaning of culture and results in stereotypes. Although the commodification of traditional lifestyles demonstrates a sense of innovativeness among Norwegians, it has reduced national characteristics, such as the roughness and stamina required that define the national identity. Secondly, the prevailing one-sided focus on nature-based tourism leaving behind the cultural, culinary, and other attributes of the Norwegian lifestyle may lead to overtourism and local conflicts, as in some Norwegian destinations given the pre-COVID-19 industry growth.

Discussion: Norwegian identity — missed potential for tourism development?

Our findings illustrate separate elements of the Norwegian identity that are to some extent already capitalized on in tourism development and marketing, as well as other identity elements implying unused potential. National identity is often commodified for economic gain, i.e., only those aspects that prove beneficial to promote are highlighted and stereotypes are fostered while national identity is only partially transported. Considering changes in tourism demand, such as the desire to immerse oneself more deeply into foreign cultures and landscapes, the wish to experience authentic places, and the willingness to challenge oneself and one’s status quo [74, Hansen A.H., Mossberg L.], it seems that the greenwashing and effeminacy of national identity are not necessary. In contrast, the peculiarities of the Norwegian landscape, the extreme light and weather conditions throughout the seasons, and the resistance and adaptiveness of Norwegians, together with other identity elements, can become a competitive strength that can also contribute to sustainable tourism development.

The identity elements can be used to strengthen existing and develop new tourist experiences. To take the example of May 17th, except for a note about the union with Sweden, the “party like no other” celebration of May 17th as a tourist experience of Norway promoted by Visit Norway does not seem to be specifically rooted in the essentialist elements of national identity, and is instead dismantled for economic gains. There is little targeted explanation of the reasons for national pride expressed in the scale of the celebration, also compared to Scandinavian neighboring countries. A mismatch between the story about and the actual core of celebration experience [75, Sundbo J., Hagedorn-Rasmussen P.] may result in inaccurate associations, particularly as “the geographic distance of the nationalities to the target destination” increases [76, Jensen Ø., Kornellussen T., p. 327]. The sensual and hedonic experience being a part of the parade without genuine understanding of the celebration could be enhanced by learning more about the core experience through contrast, authenticity, history, and interactions advancing the holistic experience, starting prior to the celebration day [9, Pedersen A.-J.].

Another example is green travel promoted by Visit Norway that can be challenged by the scholarly discussions of greenwashing for commercial benefits [17, Font X. and McCabe S.], [21, Mihalic T.]. Considering that parts of the country are covered in snow during long winter season and Norwegian nature is interpreted not only through a green lens, but also more challenging landscapes and weather conditions, it remains questionable whether these sustainable endeavors through marketing and promotion really represent the Norwegian identity as a whole. Besides, it is somewhat surprising that a male character is used in the promotional material, given the gender equality and feminine society. However, since it is the females who are generally more interested in sustainability topics and ethical consumption 30 and are often the main decision-makers and gatekeepers for holiday travel [77, Barlés-Arizón M.J., Fraj-Andrés E., Martínez-Salinas E.], it can be assumed that the male character was strategically chosen to be more appealing to the female audience.

A contradiction also lies in the touristification of cabin life. While traditional cabins are defined by simplicity, are less accessible, and require toughness to live in, the second-home tourist villages are often homogenized, easily accessible, and fully facilitated. This not only changes the character and original idea of cabin life from a design perspective, but also leads to conflict among stakeholders. With reference to fishing cabins, conflicts further evolve as traditional cabins (ror-buer), which are important markers of place identity, are commodified and monetized. These changes have also been acknowledged by Andersen L.P. et al. [46, p. 228] who summarize that “[H]istorically the Nordic landscape is both tough and generous, it both nurtures and disciplines the Nordic people, but in the contemporary utopian myth market it is mostly a source of harmony, hy-gge, and healing”. The reference to tough landscapes and discipline also encompasses the harsh weather and living conditions and long winters that are particularly experienced in the High North and shape not only everyday life, but also regional identity [57, Eika T., Olsen Ø.].

Thus, we suggest that the development and design of tourist experiences [78, Eide D.], [9, Pedersen A.-J.], should be done in a more systematic way in order to ingrain the different elements of identity toward the consistent holistic experiences before, during, and after the tourist journey. The interconnectedness of the identity elements supports the argument that a national identity is not formed in a unilateral way [e.g. top-down] and can hardly be understood from one dominant view as it is a coalescence of civic, constructivist, and essentialist elements [35, Smith A.D.]. This complexity has implications for the development of experiences, where one element can rarely be used detached from other reinforcing identity elements. For instance, the political values of the welfare state where well-being and equal opportunities of individuals mattering combined with national characteristics can serve the purposes of educational and recreational tourism. And while commodification “does not necessarily destroy the meaning” of products [79, Cohen E., p. 371] given the negotiable rather than primitive and existential rather than object-related nature of authenticity [79,

Cohen E.], [80, Wang N.], it is the intrinsic identity that attracts the growing number of tourists and could contribute to regional sustainability through bottom-up development processes. Thus, reducing commodification of the national identity calls on regional and local identities through diversification and stakeholder involvement.

Visit Norway has largely extended the tourist experience portfolio beyond the nature-based experiences: cities and places, art and culture, food and drink, family fun and shopping, and supplementing “powered by nature” with “powered by culture” slogan. While further diversification could be beneficial (e.g., travel for educational purposes or sport training), it is essential that tourism development builds on bottom-up participatory involvement of stakeholders, especially local communities, and dialog between tourism stakeholders on local/regional and national levels to embrace national identity more authentically. Diversification further requires stakeholder collaboration beyond the tourism industry, for instance with food, agriculture, and fishing industries in order to produce food experiences. While involvement of local communities could aid sustainability by integrating identity and values in tourism development, close dialog between local/regional and national tourism stakeholders could help to bring closer the communicated identity to the intrinsic one. The view on sustainability would then also transcend the economic, environmental, and socio-cultural dimensions toward the focus on communities’ quality of life. In this way, tourism could be enriched by translating identity into sustainable tourist experiences, raising “deep, meaningful emotions and memories that can encourage tourists’ contribution toward destination sustainability” fostered in “interaction with the natural environment”, “interaction with the cultural environment”, “insights and views”, and “contextual activities” [41, Breiby M.A. et al., p. 14].

The examples we found consistent with the national identity was the campaign “We survived nature for ages” and Bodø’s application for the European Cultural Capital. While the marketing campaign powerfully synthesizes aspects of Norwegianness, common national characteristics, and common culture in a serious and authentic way, this somewhat different lens is only infrequently used and is often replaced by either greening or humor. If successful, large-scale projects like Bodø Cultural Capital 2024 could generate not only short-term awareness and additional tourism revenues, but could become an accelerator of positive regional development and transformation while building on national and regional identity expressed through common culture, values, and interests as well as national characteristics and economic attributes.

Concluding remarks

The paper has synthesized the use of national identity by the Norwegian tourism industry by combining the dominant identity views, i.e., essentialist, constructivist, and civic [34, Verdugo R.R., Milne A.], and thus supplementing the business perspective on tourism and marketing with the social identity theory [8, Tajfel H.]. We have looked into the elements of common history, political and economic values, and national characteristics and celebrations, and pointed to the necessity of understanding identity being dynamic. There are several contradictory aspects in the Norwegian identi- ty, including political unity and heterogeneity, economic prosperity fostered by oil wealth and sustainability, which have been reinterpreted for tourism purposes. The use of Norwegian national identity is fragmented and sometimes inconsistent, both in literature and in the practice of developing and marketing tourism in Norway. Only certain elements of identity, such as national characteristics and traditions, have been used for tourism purposes. While Innovation Norway and Visit Norway are innovative and up-to-date in their marketing campaigns, the latter are driven by tourist demand and strikingly communicated top-down identity. We have found only a few examples of a more bottom-up identity communicated by the tourism stakeholders. Naturally, the impact of ingraining national and regional identities into tourist experiences on tourist behaviors and choices needs to be analyzed and requires empirical research.

We have argued that identity can drive sustainable tourism development [41, Breiby M.A. et al.], [81, Spenceley A., Rylance A.], [82, Storrank B.] by further diversification of tourism experiences and bottom-up stakeholder involvement [1, Høegh-Guldberg O. et al.]. Furthermore, the use of experience design and innovation tools [78, Eide D.], [42, Tarssanen S. and Kylänen M.] based on close collaboration of all the parties concerned is essential in this work. Local communities should get a chance to welcome guests to authentic places and share their own stories, which are expected to be even more in demand in post-COVID-19 tourism. Norway has already partly embarked on the Nor-wegization journey during summer 2020 due to the pandemics and reorientation in the national market. Future research will be needed to explore whether and how these new directions have contributed to sustainable tourism development, and whether tensions between residents and visitors could be reduced by involving local communities and embracing identities.

Список литературы National identity as driver of tourism development - the study of Norway

- H0egh-Guldberg O., Seeler S., Eide D. Sustainable Visitor Management to Mitigate Over-Tourism -What, Who, and How. In: Sharma A., Azizul H., eds. Over-tourism as Destination Risk: Impacts and Solutions. Bingley, UK, Emerald Publishing, 2021, 356 p.

- Harvey D. The Enigma of Capital and the Crisis of Capitalism. New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 2010, 320 p.

- Temesgen A., Storsletten V., Jakobsen O. Circular Economy - Reducing Symptoms or Radical Change? Philosophy of Management, 2019, pp. 37-56.

- Hansen A. H., Mossberg L. Consumer Immersion: A Key to Extraordinary Experiences. In: Sundbo J., S0rensen F., eds. Handbook on the Experience Economy. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2013, pp. 209-227.

- Sundbo J., S0rensen F., Fuglsang L. Innovation in the Experience Sector. In: Sundbo J., S0rensen F., eds. Handbook on the Experience Economy. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2013, pp. 228-245.

- Pike S.,Page S.J. Destination Marketing Organizations and Destination Marketing: A Narrative Analysis of the Literature. Tourism Management, 2014, no. 41, pp. 202-227.

- Viken A., Granas B. Tourism Destination Development: Turns and Tactics. Oxon, Routledge, 2014, 292 p.

- Tajfel H. Differentiation Between Social Groups. London, Academic Press, 1978, 474 p.

- Pedersen A.-J. Opplevelses0konomi: Kunsten a designe opplevelser. Oslo, Cappelen Damm Akademisk, 2012, 243 p.

- Pine B.J. & Gilmore J.H. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Harvard business review, 1998, no. 76, pp. 97-105.

- Freire J.R. 'Local People'a Critical Dimension for Place Brands. Journal of brand management, 2009, no. 16, pp. 420-438.

- White L. Commercial Nationalism: Mapping the Landscape. In: White L., ed. Commercial Nationalism and Tourism: Selling the National Story. Birstol, UK, Channel View Publications, 2017, 299 p.

- Kong W.H., Du Cros H., Ong C.E. Tourism Destination Image Development: A Lesson from Macau. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2015, no. 1, pp. 299-316.

- Jeuring J.H.G. Discursive Contradictions in Regional Tourism Marketing Strategies: The case of Fryslan, The Netherlands. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2016, no. 5 (2), pp. 6575.

- Anholt S. A Political Perspective on Place Branding. In: Go F., Govers R., eds. International Place Branding Yearbook 2010: Place Branding in the New Age of Innovation. London, UK, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, 234 p.

- Timothy D.J., Ron A.S. Heritage Cuisine, Regional Identitiy and Sustainable Tourism. In: Hall C.M., Gossling S., eds. Sustainable Culinary Systems : Local Foods, Innovation, Tourism and Hospitality. London, UK, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012, 316 p.

- Font X., Mccabe S. Sustainability and Marketing in Tourism: Its Contexts, Paradoxes, Approaches, Challenges and Potential. Journal of sustainable tourism, 2017, no. 25, pp. 869-883.

- Paasi A. Regional Planning and the Mobilization of 'Regional Identity': From Bounded Spaces to Relational Complexity. Regional Studies, 2013, no. 47 (8), pp. 1206-1219.

- Cornelissen J.P., Haslam S.A., Balmer J.M. Social Identity, Organizational Identity and Corporate Identity: Towards an Integrated Understanding of Processes, Patternings and Products. British journal of management, 2007, no. 18, pp. 1-16.

- Magnus J. International Branding of the Nordic Region. Place branding and public diplomacy, 2016, no. 12, pp. 195-200.

- Mihalic T. Sustainable-Responsible Tourism Discourse - Towards 'Responsustable' Tourism. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2016, no. 111, pp. 461-470.

- Mccool S.F. Information Needs for Building a Foundation for Enhancing Sustainable Tourism as a Development Goal: An Introduction. In: Mccool S.F., Bosak K., eds. A Research Agenda for Sustainable Tourism. Cheltenham, England, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019, 272 p.

- Papathanassis A. Over-Tourism and Anti-Tourist Sentiment: An Exploratory Analysis and Discussion. Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 2017, no. 17, pp. 288-293.

- Saarinen J. Communities and sustainable Tourism Development: Community Impacts and Local Benefit Creation in Tourism. In: Mccool S.F., Bosak K., eds. A Research Agenda for Sustainable Tourism. Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019, 272 p.

- Lamont M., Molnár V. The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 2002, no. 28, pp. 167-195.

- Govers R. Imaginative Communities: Admired Cities, Regions and Countries. Antwerp, Belgium, Reputo Press, 2018, 158 p.

- Hernández B., Carmen Hidalgo M., Salazar-Laplace M.E., Hess S. Place Attachment and Place Identity in Natives and Non-Natives. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2007, no. 27, pp. 310-319.

- Tajfel H. Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 1982, no. 33, pp. 1-39.

- Jenkins R. Social Identity. London, Routledge, 1996, 264 p.

- Eriksen T.H., Neumann I.B. Fra slektsgard til oljeplattform; norsk identitet og Europa. Internasjonal politikk, 2011, no. 69, pp. 412-436.

- Albert S. The Definition and Meta-Definition of Identity. In: Whetten D.A., Godfrey P., eds. Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 1998, 320 p.

- Skirbekk S.N. The Nordic Identity - Past, Present and Future. Foreign Ministry in Stockholm, 1992, 9 p.

- Galliher R.V., Mclean K.C., Syed M. An Integrated Developmental Model for Studying Identity Content in Context. Developmental Psychology, 2017, no. 53 (11), pp. 2011-2022.

- Verdugo R. R., Milne A. National Identity: Theory and research. Charlotte, NC, Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2016, 344 p.

- Smith A. D. National Identity. Reno, NV, University of Nevada Press, 1991, 236 p.

- Pi^tek K. Identity Dilemmas. The Case of Repatriates from Kazakhstan in Poland. In: Batdys P., Pi^tek K., eds. Alternative Memory-Alternative History: Reconstruction of the Past in the Central and Easter Europe: (Continuation, Conflict, Change). Gdynia, Poland, Bielsko-Biata, 2015, 170 p.

- Gammon S. Introduction: Sport, Heritage and the English. An Opportunity Missed? In: Gammon S., Ramshaw G., eds. Heritage, Sport and Tourism: Sporting Past - Tourist Futures. Abingdon, UK, Routledge, 2007, 168 p.

- Lundberg A. K., Granas Bardal K., Vangelsten B. V., Mathias B., Bj0rkan R., Bj0rkan M., Richardson T. Strekk i laget: En kartlegging av hvordan FNs bœrekraftsmâl implementeres i regional og kommunal planlegging. Bod0, Norway, Nordlandsforskning, 2020, 184 p.

- Pine B. J., Gilmore J. H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage. Boston, Massachusetts, Harvard Business Press, 1999, 254 p.

- Mossberg L. Extraordinary Experiences Through Storytelling. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2008, no. 8, pp. 195-210.

- Breiby M. A., Duedahl E., 0ian H., Ericsson B. Exploring Sustainable Experiences in Tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2020, pp. 1-17.

- Tarssanen S., Kylänen M. A Theoretical Model for Producing Experiences - a Touristic Perspective. Articles on experiences, 2005, no. 2, pp. 130-149.

- Eide D., Mossberg L. Toward a framework of Experience Quality Assessment: Illustrated by Cultural Tourism. In: Jelincic D., Mansfeld, Y., eds. Creating and Managing Experiences in Cultural Tourism. Singapore, World Scientific, 2019, 378 p.

- Wohlin C. Guidelines for Snowballing in Systematic Literature Studies and a Replication in Software Engineering. Proc. 18th Intern. Conf. on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering. New York, NY, United States, 2014, pp. 1-10.

- Kildal Iversen E., L0ge T., Helseth A. Reiseliv i nord: Luftfartens betydning for turismen i Nord-Norge. Menon Economics, 2017, 61 p.

- Andersen L.P., Kjeldgaard D., Lindberg F., Östberg J. Nordic Branding: An Odyssey into the Nordic Myth Market. In: Askegaard S., Östberg J., eds. Nordic Consumer Culture: State, Market, Consumer. Cham, Switzerland, Palgrave-Macmillan, 2019, 351 p.

- Andersen L.P., Lindberg F., Östberg J. Reinvention through Nordicness: Values, Traditions, and Terroir. In: Cassinger C., Lucarelli A., Gyimóthy S., eds. The Nordic Wave in Place Branding: Poetics, Practices, Politics. Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar, 2019, 288 p.

- Heslinga J.H., Hartman S., Wielenga B. Irresponsible Responsible Tourism; Observations From Nature Areas in Norway. Journal of Tourism Futures, 2019, ahead-of-print.

- Erdal M., Collyer M., Ezzati R., Fangen K., Kolas A., Lacroix T., Str0ms0 M. Negotiating the Nation: Implications of Ethnic and Religious Diversity for National Identity. PRIO Project Summary. Oslo, PRIO, 2017.

- Glenth0j R. Skilsmissen: dansk og norsk identitet f0r og efter 1814. Odense, Denmark, Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 2012, 523 p.

- Eisenträger S. Skilsmissen. Dansk og norsk identitet f0r og efter 1814 / Rasmus Glenth0j. Internasjonal Politikk, 2012, no. 71, pp. 287-290.

- Mardal M.A. Norsk historie fra 1815 til 1905. Store Norske Leksikon, 2019.

- Kaartvedt A. Kampen mot parlamentarisme. 1880-1884: Den konservative politikken under vetostriden. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget, 1967, 330 p.

- 0sterud 0. Introduction: the Peculiarities of Norway. Western European Politics, 2005, no. 28, pp. 705-720.

- Cassinger C., Lucarelli A., Gyimóthy S. The Nordic Wave of Place Branding: A Manifesto. In: Cassinger, C., Lucarelli, A., Gyimóthy, S., eds. The Nordic Wave in Place Branding: Poetics, Practices, Politics. Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar, 2019, 288 p.

- Warner-S0derholm G. But We're Not All Vikings! Intercultural Identity within a Nordic Context. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 2012, no. 29, pp. 1-19.

- Eika T., Olsen 0. Norsk 0konomi og olje gjennom 100 ar. Samfunns0konomen, 2008, no. 8, pp. 3243.

- R0ed H. Et hav av muligheter: Hva skal vi leve av etter oljen? Oslo, Humanist forlag, 2020, 211 p.

- Stamnes E. Fisk eller olje?: Den norske debatten om petroleumsvirksomhet i nord. En studie av akt0rer og argumenter i perioden 1960-2006. Masteroppgave. Oslo, UiO, 2009, 117 p.

- 0ian H., Fredman P., Sandell K., Dóra Sœbôrsdôttir A., Tyrväinen L., S0ndergaard Jensen F. Tourism, Nature and Sustainability: A Review of Policy Instruments in the Nordic Countries. Copenhagen, Denmark, Nordic Council of Ministers, 2018, 99 p.

- Hagen L.F., Kristoffersen K.J. 800 bes0kende om dagen f0rer til at steiner faller i hodet pa turgaere pa Reinebringen. Nordland, NRK, 2019.

- Vistad O.I., Vorkinn M. The Wilderness Purism Construct — Experiences from Norway with a Simplified Version of the Purism Scale. Forest Policy and Economics, 2Q12, no. 19, pp. 39-47.

- Martin D.M., Lindberg F., Fitchett J. Why Can't They Behave? Theorizing Consumer Misbehavior as Regime Misfit Between Neoliberal and Nordic Welfare Models. In: Askegaard S., Östberg J., eds. Nordic Consumer Culture: State, Market, Consumers. Cham, Switzerland, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, 351 p.

- Seeler S., Schänzel H.A., Lück M. 2Q2Q. 'Let's Travel Where the Wi-Fi is Weak - But Let Me Share My Location First': Paradoxes and Realities of Off-the-beaten-track Tourists. Auckland, NZ, CAUTHE, 2020.

- Brochado A., Pereira C. Comfortable Experiences in Nature Accommodation: Perceived Service Quality in Glamping. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 2Q17, no. 17, pp. 77-83.

- Pamment J. Introduction: Why the Nordic Region? Place Brand Public Dipl, 2Q16, no. 12 (2-3), pp. 91-98.

- Gullestad M. Naturen i norsk kultur. Forel0pige refleksjoner. In: Deichman-S0rensen T., Fr0nes, I. [eds.] Kulturanalyse. 1990.

- L0kka N. Dagens vikingtid. Ottar, 2015, no. 2, pp. 51-56.

- Johansen A. Sjelen som forretningsidé. Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift, 1991, no. 82, pp. 99-117.

- 7Q. Sanin J. From Risky Reality to Magical Realism: Narratives of Colomgianess in Tourism Promotion. In: White L., ed. Commercial Nationalism and Tourism: Selling the National Story. Bristol, UK, Channel View Publications, 2Q17, 299 p.

- Seeler S. Commercial Nationalism and Tourism - Selling the National Story. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 2Q17, no. 9, pp. 346-348.

- Fu Y., Liu X., Wang Y., Chao R.-F. How Experiential Consumption Moderates the Effects of Souvenir Authenticity on Behavioral Intention through Perceived Value. Tourism Management, 2Q18, no. 69, pp.356-367.

- Hume D. L. Tourism Art and Souvenirs : The Material Culture of Tourism. London, UK, Routledge, 2014, 197 p.

- Hansen A. H., Mossberg L. Tour Guides' Performance and Tourists' Immersion: Facilitating Consumer Immersion by Performing a Guide Plus Role. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2017, no. 17, pp. 259-278.

- Sundbo J., Hagedorn-Rasmussen P. The Backstaging of Experience Production. In: Sundbo J., Darmer P., eds. Creating Experiences in the Experience Economy. Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar, 2QQ8, 262 p.

- Jensen 0. & Kornellussen T. Discriminating Perceptions of a Peripheral 'Nordic Destination' among European Tourists. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2QQ2, no. 3, pp. 319-33Q.

- Barlés-Arizón M. J., Fraj-Andrés E., Martínez-Salinas E. Family Vacation Decision Making: The Role of Woman. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2Q13, no. 3Q, pp. 873-89Q.

- Eide D. Opplevelseskvalitet: Et faglig rammeverk for kvalitetsvurdering og - utvikling i opplevelsesbasert reiseliv. Praktisk 0konomi og finans, 2Q2Q, no. 36, pp. 122-137.

- Cohen E. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 1988, no. 15, pp. 371-386.

- Wang N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 1999, no. 26, pp. 349-370.

- Spenceley A., Rylance A. The Contribution of Tourism to Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. In: Mccool S.F., Bosak K., eds. A Research Agenda for Sustainable Tourism. Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2Q19, 272 p.

- Storrank B. Unlocking Regional Potentials: Nordic Experiences of Natural and Cultural Heritage as a Resource in Sustainable Regional Development. Copenhagen: Nordisk Ministerrad, 2Q17, 115 p.