Nature-culture-health promotion as community building

Автор: G. Tellnes , Batt-rawden K.B. , Christie W.H.

Журнал: Вестник Международной академии наук (Русская секция) @vestnik-rsias

Рубрика: Проблемы экологии, образования, экологической культуры, науки о земле

Статья в выпуске: 1, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

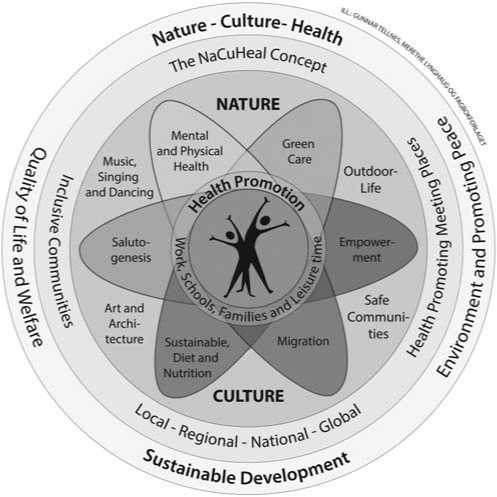

Recent research confirm that longevity and a healthy life is strongly influenced by belonging to closely knit communities or groups, that can give you a sense of meaning, belonging and a sense of coping through collective activities. New health chal lenges means that new and diverse networks have to be created in order to achieve interdisciplinary collaboration. Such net works should provide mutual assistance within and between countries and facilitate exchange of information on which strate gies are effective in which settings. This paper describes research studies that show how «nature and cultural activities» can promote health, quality of life and environment for individuals and create healthy local communities. At the Centre for NatureCultureHealth in Asker, a suburb west of Oslo, there have since 1994 been several experiments where individuals from the local population have been helped to find their own talents and capacity for work to maintain function and pleasure in work. Through participation in NatureCultureHealth activitygroups (NaCuHeal) the individual will find the opportunity to participate in dancing, music, art, physical activity, nature walks, hiking, gardening or contact with pets. Access to nature is a determinant of health, and lack of this will be a contributing factor to increased social inequality in health and welfare. Culture like art and music is socially significant in ways to act as a medium that allow people to connect with others, which allows bridge building and creates friendships, establishes and/or reestablishes social networks and local communities. Safety Promotion and injury prevention should also be natural part of NatureCultureHealth promotion in order to strengthen The Public’s Health.

Health promotion, prevention, rehabilitation, public health, local community, naturculturehealth, nacuheal

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143162070

IDR: 143162070

Текст научной статьи Nature-culture-health promotion as community building

Health promotion goes beyond health prevention in that it not only aims to reduce potential health impairments, but also seeks to build resilience and evolve better conditions for healthy adaption in life for all. Recent research confirm that longevity and a healthy life is strongly influenced by belonging to closely knit communities or groups, that can give you a sense of meaning and of mastering in collective activities. Increasingly more emphasis has been put on cultural activities for maintaining health and quality of life [13, 23. 44], and may be linked to the building of social capital in local communities [11]. Gillies [21] has argued that health promoters need to be involved in helping to repair the social fabric of society by building social capital. High levels of trust, positive social norms and overlapping and diverse horizontal networks for communication and exchange of information, ideas and practical help characterize communities with a high level of social capital [15]. Both normal people and those with impaired health will benefit from the development of this social capital1.

Rapid processes of change in the community represent a challenge to public health policy [37, 39, 40, 42]. Health promotion is carried out by and with people, not on or to people (WHO, 1997). It improves both the ability of individuals to take action, and the capacity of groups, organisations or communities to influence the determinants of health. «Settings for health» represent the organisational base of the infrastructure required for health promotion. New health challenges mean that new and diverse networks need to be created to achieve inter-sectoral collaboration. Such networks should provide mutual assistance within and between countries and facilitate exchange of information on which strategies are effective in which settings [17].

NatureCultureHealth — activites (NaCuHeal) may promote health in local, regional, national and global settings (Tellnes 2017). The purpose of NaCuHeal is to promote health, quality of life and welfare.

The NatureCultureHealth Centre in Asker, Norway

Partnerships for health promotion were created to achieve inter-sectoral collaboration in a local community in Norway [4]. The purpose of the concept «NatureCultureHealth Interplay» (NaCuHeal) aim was to create a common arena and forum for wholeness thinking and creativity, in order to improve environment, quality of life and health among people in the local community [36]. The challenge was to get various interest groups, i.e. public agencies, private businesses, voluntary organisations and pioneers to co-operate in order to develop the idea to be realized in health promoting settings [40, 41].The center is now one of the official partners of public health at the county level as well as the municipality level (.

At the Centre for NatureCultureHealth (NaCuHeal) in Asker, a suburb west of Oslo, there have since 1994 been several experiments where individuals from the local population have been helped to find their own talents and capacity for work to maintain function and pleasure in work. At the NaCuHeal-centre it is desirable with participation and positive interactions between persons of all ages, health status, philosophies and social positions. The idea is that such a meeting place between practitioners and theorists, between the presently well and the presently not so well, will be stimulating and enlightening to most people. Through participation in NatureCultureHealth activity-groups the individual will find the opportunity to bring to life his or her own ideas by emphasizing positive and creative activities outside one self. At the same time, NaCuHeal-activities may nourish other sides of one's personality that may also need development, attention and strengthening, to prepare for community and new social networks. The NaCuHeal activities thus can strengthen the social capital [15], and functional ability of the participants or population included [4, 6].

Many individuals have through different NaCuHeal activities experienced that e.g. dance, music, art, physical activity, nature walks, hiking, gardening or contact with pets give an indirect effect with feelings of zest for life, inspiration and desire for rehabilitation. The activities seem to strengthen the ability to cope, improve quality of life and enable us to meet everyday life in a positive manner. For many people long-term certified sick, this has been a method for return-to-work [5, 6]. The direct route through occupational rehabilitation may be of help to some people. For others, however, it may be necessary to take a more indirect and creative route to succeed in their rehabilitation, i.e. to practice and participate in NaCuHeal-activites for later to achieve a more useful and active existence. The way through such creative activities may give each individual a feeling of meaning and desire to act.

There is reason to believe that there is still an untapped potential for improving public health by employing health-promoting nature and cultural activities. Maintaining self and cultivating strategies of self-care in everyday life are vital aspects to improve public health in a salutogenetic perspective [3, 28]. The focus in saluto-genesis [3] is how to enter into a good circle, a positive feedback loop [25, 26].

This is also a great challenge to our new multicultural and urban society. The goal is increased ability to cope, productivity and prosperity to all people, i.e. not only the affluent members of society, but also the ones who are in danger of becoming permanently incapable of working. New health challenges means new and diverse networks and new methods of public health research need to be developed and created. Synthetic research methods, probably have to be applied in order to evaluate this community approach to public health. Perhaps it is timely to bring forth to a further extent the unique qualities of nature [18] and the value of art [12]. Public health research and practice should focus not only on factors causing disease and injuries (pathogenesis), but also on factors promoting health (salutogene-sis) in the perspective of health promotion and prevention in different settings.

There is both a strong political and economic rationale for governments to invest more in community based public health research and practice. The World Health Organisation (WHO, 1997) therefore has significantly supported the shaping of health promoting settings at work, in hospitals, in schools and in local communities. Health promotion requires partnerships for health and social development between the different sectors at all levels of the community.

Salutogenic Potentials in Nature

Nature as a place where you belong, a landscape with a cultural heritage that you recognize as «yourself» is a vital health resource [18, 27]. Sense of belonging is a central topic in recent book where new findings in psychology, neuroscience and evolutionary biology may build and create new politics: a 'politics of belonging' [29] According to Max Weber [46] modern man has imprisoned himself in the iron cage of rationality. Effectiveness, cost-benefit analysis, long term planning, seriousness and cleverness colonize our lives. We are high achievers in a world of The Duty.

Feelings for nature are generally a mix of deeply rooted, evolutionary feelings and various cultural aspects, and secondly much of morally derived concern and love for nature has a recent, and thus cultural flavour. Nature may contribute to a proud and stable identity. Historians describe how the Apache Indians focus their identity and history in places. The Indians call this «place making», a transformation of landscape as nature into a social construction that gives identity [20]. In Norway, the closeness between nature, home place and identity is reflected in our surnames Li (Valleyside), Bjerke (Birch), Aas (Hill), Steinberg (Stonehill). They are mostly composed of phenomena, structures and creatures in nature.

Much of human cultural evolution has been about creating distance to nature, the physical struggle for life and the immoral animals, which should be seen as a legitimate goal [10]. The flipside of this movement has been a complete isolation from nature for many urban people and hence a strong feeling that something is missing. The point is, whether humans well-being related to nature has an evolutionary or cultural origin, the arguments for preserving allowing access to nature in some form are similarly legitimate and have the same positive influence on human health. The fact that most basic cultural attributes have been modified from, and developed, from evolutionary responses researches further argues against a strict separation between natural and cultural affinities for nature [27]. This is of great importance when it comes to community building that promotes health.

Three Theories

Theories have been proposed to explain nature's restorative benefits and it may be useful to distinguish between affective and cognitive benefits of nature.

-

1. Stress reduction theory (SRT) by Ulrich et al. [45] assumes that natural environment has an invigorating advantage and reduces stress compared to artificial environments because of our innate connection to the natural world. Natural landscapes; grasslands with clusters of trees seem to be places with opportunities for health benefits, and a «haven» where body and soul feels unified. A number of studies [45] demonstrated the importance of visual contact with trees rather than e.g. concrete buildings walls. Postoperative patients reported less pain, less fear and were healed earlier when viewing trees rather than walls.

-

2. Attention Restoration Theory (ART) highlights that urban environments requires people's ability to filter relevant stimuli from irrelevant stimuli, particularly where urban environments seem to deplete our cognitive resources [24]. According to Attention Restoration Theory, natural environments invokes one different kinds of attention from people — a sense of «fascination» and «being away», which can lead to better performance in tests measuring memory and attention.

-

3. Biophilia hypothesis [48] argues that people have a biologically based needs to attach to and feel connected to the wider natural world. A number of studies confirm the overall positive physical and mental stimulus experiencing nature. Certain visual images of nature

have more appeal than others and typically «savanna-like» landscapes have been seen as the archetype of nature where our aesthetic preferences have been attributed evolutionary traits. Cultural landscapes often mimic these aesthetic qualities. The «wilderness» nature may have other qualities, but in both cases biodiversity per se is a core value both of the cultural landscape as well as the wilderness. Interestingly in the wilderness, where much of the more charismatic biodiversity (e.g. large fauna) rarely is encountered, simply the awareness of their very existence in nature may support positive emotions and thus well-being.

Ecological Aspects

An ecological approach to development and learning is the perception and action perspective introduced by Gibson [19] as the Theory of Affordances. The term «affordances» describes the functions environmental objects can provide to an individual. For example, if a rock has a smooth and horizontal surface, it affords a person a place to sit. If a tree is properly branched, it affords a person the opportunity to climb it. This exemplifies an intertwined relationship between individuals and the environment and implies that people assess environmental properties in relation to themselves, not in relation to an objective standard. The role of access to green spots and nature for humans well-being has been grossly underestimated [24, 34]. The challenge of green design is to integrate into buildings the positive biophilic features of our evolved relationship with nature and to avoid biophobic conditions 10, 48] .

With increasing urbanization, people have less access to nature in their daily life. In general, people in the Western societies spend most of their time in indoor settings. Integrating features of natural contents into the built environment can give people access to nature, to a greater degree. Research on this topic has the potential for helping planners and other environmental designers to influence properties of the built environment that can promote health and wellbeing both in hospitals and in other built environments [34, 39].

Compared to the man-made urban surroundings with their embedded socio-material expectations and demands, nature gives an open address where we are free to embark on simple projects, providing the individual with experiences of autonomy, competence and control. These experiences can counterweight those of the modern life, where we are met with demands not chosen by ourselves, and seldom can see immediate results of our own deeds. To walk into the forest means, symbolically speaking, to enter one's own self [47]. At the level of emotion and agency, rather than an analytic, meeting with nature, also means relating to what elements in nature stand for. Without ecological health there can be no human health.

Salutogenic Potentials in Culture — Music and Choral Singing

For centuries, then, music has been recognized for its therapeutic properties in healing the body and mind and for treatment of physical or mental illness. Music has even been used by pre-literate people for communication at a distance. The perception of communication between souls may be grounded in shared experience [35] thus research shows how people describe musical highlights in their lives as being connected to a shared music-making, one that creates togetherness and connectedness, and one that is fun, enjoyable [5, 8, 12]. Tchaikovsky once wrote: «truly there would be reason to go mad if it were not for music» [35]. Group singing appears to positively influence emotional, social and cognitive processes in ways that stimulate participants [7]. Previous population studies and a human-intervention study have shown that religious, social and cultural activities predict increased survival rate [13]. Almost all these activities are performed together with other people, connecting to social support as an important factor for health [32].

The majority of participants reported improved health, quality of life and functionality when included in a programme of local community-based Nature-Culture-Health (NaCuHeal) activities, and choral singing was reported as particularly beneficial and empowering [6]. Singing can also be beneficial for those in the wider community who are affected by non-communicable diseases such as cancer [31]. Vitality was improved in those with a cancer diagnosis, and anxiety was reduced in carers and the bereaved.

The emerging focus on music and medicine is part of a rising interdisciplinarity in health research, one in which there has been a growing interest in evidencebased knowledge [5, 10, 14]. This interdisciplinary trend can be seen through various developments. For example some authors suggest that nurses should be taught how to incorporate music interventions into their practice to more effectively manage anxiety and individualize patient care [9, 16]. In community music therapy, which deals with neurology, music therapy, music sociology and social psychology of music, this interdisciplinary trend is demonstrated [1]. As Stige [33] argues, by developing knowledge about healing rituals of different cultural contexts one may develop one's own cultural sensitivity, which will be increasingly important as more and more music therapists are working in multicultural contexts.

A focus here is to understand how members of a community or setting make sense of their world and to respect or recognize their lay knowledge and practices — that is, an awareness of social and cultural context and how music takes on meanings within these contexts. This focus extends music therapy's holistic perspective from its original focus on the individual to a focus on the individual in a group, and as such it begins to address concerns highlighted in social psychology of music — the need for a focus on music in naturalistic contexts of use. This emphasis on local musical practices has helped to highlight musical activity's role in producing social capital2 and in turn enhancing quality of life [9].

Through the intimate frame given by musical activity, individuals are bound together through common musical experiences. As Ruud [32] argues, being with others may provide intense experiences of involvement, and a heightened feeling of being included; music thus becomes a social resource. Ruud builds here on the work of Antonovsky [2], and argues how the individual's sense of coherence and meaning in life could contribute to the general resources of resistance toward illness. In the sense that our musical experiences are remembered or felt as being significant, this relates to discussions concerning emotional and bodily involvement in music. From this viewpoint, music is a type of «aesthetic behaviour» that may protect or retain health or prevent ill-health.

Final Comments

World Health Organization (WHO) have described why strengthen community resilience in the document: «Health 2020 — A European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. The WHO Small Country Initiative». This document states that «building resilience is a key factor in protecting and promoting health and well-being at both individual and community levels». The development of supportive environments is instrumental in building resilience, which has an impact

Список литературы Nature-culture-health promotion as community building

- Ansdell G. How Music helps in Music Therapy and Everyday life. Surrey, UK, Ashgate. 2015.

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, London: JosseyBass Publishers. 1987.

- Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 1996; 11 (1): 11-18.

- Batt-Rawden K.B., Tellnes G. NatureCultureHealth Activities as a method of rehabilitation; An Evaluation of Participants' Health, Quality of Life and Function. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. Res. 2005; 28: 175-180.

- Bailey B., Davidson J. Effects of group singing and performance for marginal ized and middleclass singers. Psychology of music.2005; 33 (3): 269-303.

- Boer D. How share preferences in music create bonds between people: values as the missing link. Pers. Soc.Psychol.Bull. 2011; 37: 1159-1171.

- Tellnes G. The Nature -Culture -Health Interplay. Вестник Международ ной Академии Наук, Русская секция, Special issue, 2009.

- Tellnes G., Lund J. Injury prevention and safety promotion in a local community -20 years experience from Norway. Вестник Международной Акаде мии Наук. Русская секция, 2007; 2: 12-15.

- Ulrich R. S., Simons R. F., Losito B. D., Fiorito E., Miles M. A., Zelson M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 1991; 11 (3): 201-230.

- Weber M. Writings Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought. Ed. Peter Lassman. Trans. Ronald Speirs. Cambridge UP, 1994.

- Wickström B. M., Ingeberg, M. H., Tellnes, G. BattRawden, K. B. Meaningful cul tural activities and encounters increase a person's social capital and decrease individuals experiencing stress or anxiety. 4th European Public Health Conference. HIOA, ØF, UiO 2011.