On the origins of niello

Автор: Giumlia-mair А.

Журнал: Краткие сообщения Института археологии @ksia-iaran

Рубрика: Материалы конференции "Актуальные проблемы современной археометаллургии" 14-15 апреля 2022 г.

Статья в выпуске: 271, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper presents a study on the earliest examples of niello scientifically identified up to now. Niello is a black material consisting of one or more metal sulfides that can be used as decorative filling in keyings or channels cut on metals. On the origins of niello there exists quite a few misunderstandings and confusion, because in the past all black materials on metals were called “niello” without any discrimination between different substances and techniques. For instance, formerly it was believed that niello was employed in Egypt and in the Mycenaean world in the mid 2nd millennium BC, however various studies in the nineties of the last century demonstrated that the earlier black inlays on metal objects are not metal sulfides, but copper-based, artificially black patinated alloys. After the identification of the black patinated alloys it was then supposed that niello had been invented by the Romans, because it seemed that the earliest instances of decorative black sulfides on metal appeared in the 1st century CE. However, at the end of the nineties of the last century, three different instances of niello were identified on Late Classical and Early Hellenistic objects. In the meantime, more examples of early niello have been discovered and confirm the existence of this material in the 5th-4th century BC. The method employed for the identification of niello on the various objects has been X-ray Diffraction (XRD) in most cases. In some cases, when sampling was not allowed, non-destructive methods such as Energy Dispersive Spectrometry in the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM-EDS) was employed when the objects were small enough to be put into the SEM chamber. When the objects were larger X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) was used. In some other instances, only an autoptic examination of some pieces was sufficient to establish if a black material had been applied on specific objects or not. This paper discusses the new discoveries and discusses the possible area of origin of this decorative material.

Niello, metal sulfides, keying, rhyton, black sea, x-ray diffraction

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143182415

IDR: 143182415 | DOI: 10.25681/IARAS.0130-2620.271.243-255

Текст научной статьи On the origins of niello

Niello is a black, dark gray or bluish-black material consisting of one or more metal sulfides applied into a keying cut into metal objects. The metals employed for the items ornamented with niello are mainly made of silver or quaternary alloys, consisting of copper containing tin, zinc, and lead, or, later, made of brass.

In antiquity three kinds of this black decorative material seem to have been in use ( Giumlia-Mair , 1998; 2000). The earliest scientifically identified examples of niello seem to have been of the monometallic variety, made of the same metal on which the niello was applied, i. e. silver on silver alloys, and copper on copper-based alloys mixed with sulfur. This earliest kind was mostly employed in the 1st c. AD in the Roman Empire, as La Niece’s research on this topic demonstrated ( La Niece , 1983), but, as more analyses revealed in the nineties of last century, earlier examples existed outside of the Roman empire in the regions around the Black Sea as early as the 5th century BC ( Giumlia-Mair, La Niece , 1998).The second variety that had been mainly used after the 5th century AD was the bimetallic kind, consisting of copper and silver mixed with sulfur.

After the 11th century AD, it seems that mainly trimetallic niello, consisting of silver, copper and lead mixed with sulfur was employed. Nevertheless, we must keep in mind that up to now not many objects decorated with niello have been analyzed and they mostly come from museum collections in Western European countries. Only very few objects from Eastern European countries have been studied, therefore the general picture we possess up to now, might change when more such objects can be analyzed.

Methods of analysis

The main method employed for the identification of niello on the various objects has been X-ray Diffraction (XRD) in most cases.

When sampling was not allowed, non-destructive methods such as Energy Dispersive Spectrometry in the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM-EDS) was employed, when the objects were small enough to be put into the SEM chamber. When the objects were too large for the SEM chamber X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) was used.

In some other instances, only an autoptic examination of some pieces was suffi-cient to establish if a black material had been applied on specific objects or not.

Materials that can be mistaken for niello

Several archaeological materials, decorated with black substances can easily be confused with niello, if the archaeologists are not aware of the problems involved with the identification of black decorative materials. Before the studies on niello carried out by Susan La Niece (La Niece, 1983) and those by Paul Craddock and myself, several well-known black-patinated Egyptian and Mycenean objects had been considered to be made of niello. Our analyses demonstrated that they are instead artificially black-patinated copper-based alloys containing small amounts of gold, silver and arsenic, typically around 1–3 % Au, and 0,3–1 % Ag and/or As (Gium-lia-Mair, Craddock, 1993; Giumlia-Mair, 1996; 1997; 2013; Giumlia-Mair, Quirke, 1997; Giumlia-Mair, Riederer, 1998; Giumlia-Mair, Kanta, 2021). These alloys could be patinated in various ways, the best known of which consists of dipping the objects in a hot solution containing copper salts, vinegar, and alum (Giumlia-Mair, Lehr, 2003). These materials clearly have nothing to do with niello. Distinguishing these two materials with a proper autoptic examination and a simple XRF analysis carried out by a trained person is relatively straightforward: niello normally looks glassy, is fragile, sometimes shows some very small bubbles and it is a sulfide. The second material that is also much older, is metallic, malleable and patinated, besides containing small amounts of elements like gold, silver, and arsenic. Very often the artificial patina is slightly damaged and shows the red metal of the alloy, as it is for instance the case with the relatively recently excavated dagger from Knossos, in Crete (Giumlia-Mair, Kanta, 2021).

Dark enamels, such as some of those known from ancient Egypt, but also from other contexts and in different periods, particularly if they have been altered by the long permanence in the soil, can sometimes be taken for niello. This can happen especially if the enameling technique is that of champlevè that looks similar to that of niello, because it also involves the cutting of the metallic surface to produce a keying that can be filled with vitreous material. The object is normally fired to melt the enamel so that it fills all parts of the keying and finally the cooled down enamel is polished. In this case too, a simple examination and analysis for example with SEM-EDS can dispel all doubts on the nature of the material.

In Medieval times, especially in Islamic countries, luxury objects made of brass or quaternary alloys were decorated by incising the surface, as with niello and cham-plevé enamel, and applying bitumen in the carved channels. The final result is a very pleasing black and «gold» decorative object that can be taken for niello as well.

In some cases, instead of using bitumen, black pitch was used to obtain the same kind of effect.

The famous Roman encyclopedist and author Gaius Plinius Secundus, also known as Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD), mentions the use of a bimetallic niello in Egypt, but also a second interesting method for blackening silver with yolk in his Naturalis His-toria (Plin., Nat. Hist., 33, 131):

The people from Egypt stain their silver so as to see portraits of their god Anubis in their vessels; and they do not engrave but paint their silver. The use of that material thence passed over even to our triumphal statues, and, wonderful to relate, its price rises with the dimming of its brilliance. The method adopted is as follows: with the silver is mixed one third of its amount of the very fine Cyprus copper, called coronarium and the same amount of live sulfur as of silver, and then they are melted in an earthenware vessel having its lid stopped with potter’s clay; the heating goes on till the lids of the vessels open of their own accord. Silver is also turned black by means of yolk of a hard-boiled egg, although the black can be rubbed off with vinegar and chalk.

Clearly the time of execution of the various operations described above can vary conspicuously and this also affects the value and cost of the objects.

Methods of production and application of the different kinds of niello

As already mentioned, the earliest scientifically identified variety of niello is the monometallic one and it was prepared by mixing in a sealed crucible fragments, foil, or■ filings of metal (copper or silver) with sulfur and a flux, like for example borax. The mixture was heated, and a black, fragile, and almost glassy material was obtained. This means that the copper or silver employed in the production of niello lost all typical properties of metals, such as color, sheen, malleability, and ductility. This black material was then crushed by pounding it in a mortar, ground until it was reduced to powder, then mixed with borax and re-heated to ca. 600 °C, when it reached the consistency of a paste. It is important to note that the monometallic kind of niello could not be completely melted. The melting point of silver sulfide is 861 °C; that of copper sulfide is 1121 °C. Should a complete melt of this kind of niello have been attempted, the black mass would have lost its sulfur by sublimation and would have reverted to metal again. As example of this phenomenon, we can mention the silver spoons from the «treasure» of Isola Rizza, now in the Museo Civico at Verona ( Bolla , 1999. P. 278). The spoons show the Latin good luck wishing formula VTERE FELIX – use (me) happily – and the sentence was originally picked out in niello, but now the recesses are filled with silver, most probably because the objects had been heated in the past during conservation, so that the niello lost its sulfur and turned again to silver.

For this reason, the artisans had to use monometallic niello at a lower temperature of around 600 °C, when it had the consistency of a paste that could be pressed into a keying cut into the metal object that had to be decorated ( Maryon , 1954; Moss , 1953; Giumlia-Mair, La Niece , 1998). To obtain a better hold of the niello paste on the metal underneath the internal surface of the keying was often roughened with the chisel. Niello produced in this way is less solid than the ones prepared as bi- or trimetallic mixture, because they have a lower melting point and become more liquid. Therefore, they can more easily fill all recesses of the keying cut on the metal of the object.

The bimetallic variety of niello consists of copper and silver mixed with sulfur, prepared in a crucible in the same way as the monometallic variety. Its melting point is lower than that of the previously described variety consisting of only silver and sulfur or copper (as well as bronze or brass) and sulfur, so that the black material can be fused at ca. 680 °C directly inside the keying prepared on the object to be decorated and has a significantly better bonding to the metal underneath.

This kind of material is described in the 1st century AD by the famous encyclopedist Pliny in his Naturalis Historia in the paragraphs dedicated to silver: id autem ^t hoc modo: miscentur argento tertiae aeris Cyprii tenuissimi, quod coronarium vo-cant, et sulpuris vivi quantum argenti; con^antur ita in ^ctili circumlito argilla; modus coquendi, donec se ipsa opercula aperiant («The method adopted is as follows: with the silver is mixed one third its amount of the very fine Cyprus copper called chaplet-copper and the same amount of live sulphur as of silver, and then they are melted in an earthenware vessel smeared round with potter’s clay; the heating goes on till the lids of the vessels open of theft own accord») (Plin. Nat. Hist., 33, 131).

Nevertheless, from the analytical data we possess up to now, it seems that this recipe was used only occasionally in Roman times and became common only after the 5th century AD ( Moss , 1953; Dennis , 1979; La Niece , 1983. P. 280).

The third variety of niello is the trimetallic kind and it consists of silver, copper, and lead sulfides. This decorative material has a much lower melting point than that of the previously discussed varieties: it can go from 440 to 560 °C, depending on the proportions of copper and lead added to the silver and – being very fluid – it can be poured into the channels of the keying, where it fills even the finest details. This has been the preferred variety since the 11th century AD, certainly because of its convenient working properties. Very similar working properties are achieved when leaded copper-based alloys are employed in its preparation. Recipes of niello made of leaded bronze or leaded brass are mainly employed on the same kind of metal they are made of, while trimetallic niello, in which silver is one of the components, is used almost exclusively on objects made of silver alloys. The trimetallic variety of niello has been widely employed in various contexts in the Middle Ages and in later periods, from Viking Scandinavia to the Italian Renaissance and notably in 18th and 19th century Russia.

Early examples of niello

The silver rhyton (Fig. 1: 1 ) now in the Museo di Antichità J. J. Winkelmann at Trieste, Italy, was found in a grave, during an excavation at Taranto, at the end of the 19th century and was bought by the Director of the Trieste Museum in 1889 ( Giumlia-Mair, La Niece , 1998), when Trieste was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At that time antiquities could be legally bought and sold without problems, even over the borders of the respective countries. The beautiful vessel is dated to the end of 5th c. BC and it represents a fawn with sprouting antlers or a young deer. The repoussé frieze on the neck represents the myth of Boreas and Oreithyia. She was an Athenian princess and the daughter of the legendary king of Athens Erechtheus. The god Boreas, supported by the goddess Athena and by the princess’ father (both represented on the frieze) seized her and carried her off to Thrace, where she became his wife, as well as the goddess of cold winds, and gave birth to the wind gods Kalais and Zetes. The Athenians interpreted the destruction of 1200 Persian ships by a gale near Cap Artemision in the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, as an intervention of Boreas and Oreithyia.

The choice of the myth for the frieze on the neck of the vessel is important for the exegesis of the object because it has been interpreted as a political expression of the Thracian wish of being allies of Athens ( Dörig , 1987. P. 9). Many scholars agree on the connection to the Thracian sphere and suggest a provenance from the Black Sea area, Thrace, or Asia Minor for the silver rhyton ( Puschi, Winter , 1902; Simon , 1967; Giumlia-Mair, La Niece , 1998). The stylistic and technological comparisons with similar vessels from the Black Sea area, such as for example the rhyton from Rozovets, but also more examples, seem to confirm this provenance ( Маразов , 1978; Giumlia-Mair, La Niece , 1998). Pfrommer discussed the rhyton and suggested

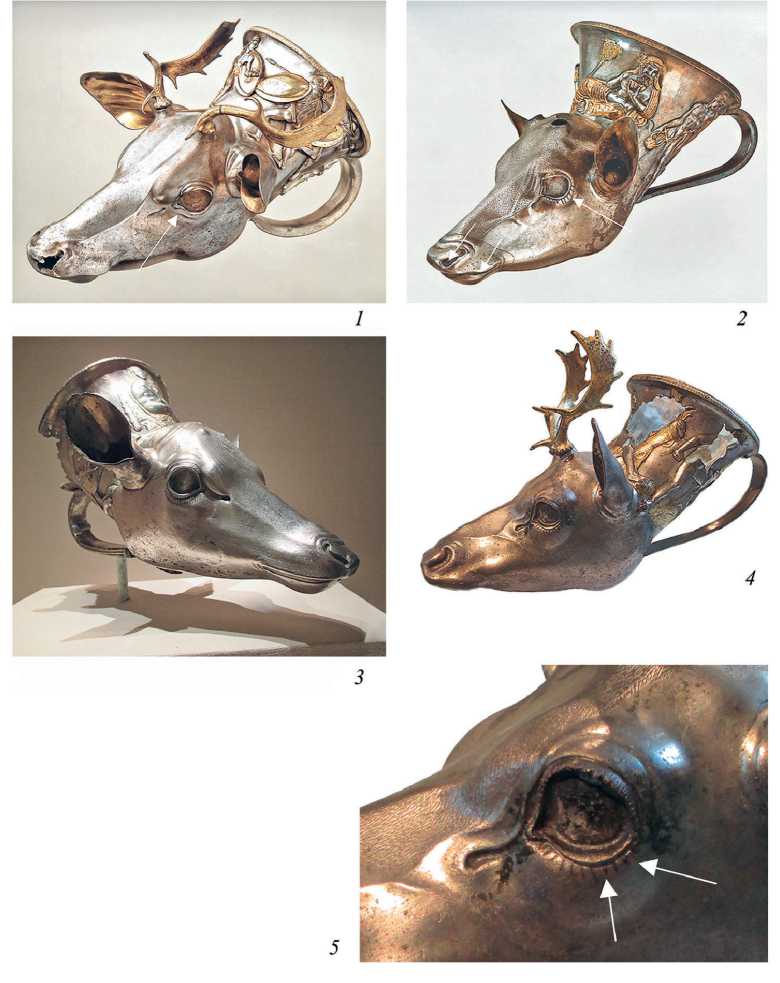

Fig. 1. The rhyton from Taranto decorated in niello technique

1 – The rhyton, now in the Winkelmann Museum at Trieste (Italy). The nose, mouth and eyes are underlined with niello. Dated ca. 510 BC (after: Giumlia-Mair , 2002); 2 – Detail of the niello on the right eye of the fawn (Photo A. Giumlia-Mair)

an explanation for the presence of this vessel in southern Italy: in 330, after the victorious battle of Granikos, Alexander the Great sent part of his booty, taken from the palaces of the Satraps of Asia Minor, to Kroton i. e., to his allies in southern Italy ( Pfrommer , 1983). Tarentine objects of this period are characterized by oriental motifs that were not present before and might have been inspired by the arrival of precious objects belonging to Alexander’s booty in the region. The magnificent silver rhyton from Trieste might have been part of it.

The niello is found on the eyes (Fig. 1: 2 ), nose and mouth of the fawn and it is quite well preserved. In 1997, for the study and the X-ray diffraction analyses

(henceforth XRD) and energy dispersive analyses in the scanning electron microscope (henceforth SEM-EDS) I carried out together with Susan La Niece of the British Museum, I took ten small powder samples (a few fine grains, less then 0,5 mg) from different areas of the niello. The analyses showed that the niello on eyes, nose and mouth consists of the silver sulfide acanthite (Ag2S), while the niello inside the nostrils is a mixture of the silver-copper■ sulfide jalpaite (IIIAg1.55 Cu0.45 S) and the lead sulfide galena (PbS) ( Giumlia-Mair, La Niece , 1998).

The presence of acanthite on eyes, nose and mouth and of complex sulfides in the nostrils of the fawn represented on the 5th century BC vessel was quite a surprise, because, after the studies of Susan La Niece on niello, it was thought that monometallic niello had been only in use from the 1st century AD, while trimetallic niello should have been a material only known after the 11th century AD ( La Niece , 1983).

As one instance is not sufficient for establishing the existence of a technique in any given period, more examples of similarly dated nielloed objects had to be identified.

The rhyta of the Ortiz Collection

Parallels to the Trieste rhyton were easily found in the G. Ortiz Collection in Geneva, to which two magnificent examples of silver rhyta belong ( Ortiz , 1996. P. 152, 154). Regrettably both pieces come from the international art market and lack an official ascertained provenance, but the reported origin is the region around the Black Sea (with all probability the Northern coast of Asia Minor). The first, very large, piece (L. 29 cm) represents a stag’s head with gilded horns (Fig. 2: 1 ). The inside of the ears, details of the frieze, of the handle and the rim of the vessel’s mouth are also gilded. The frieze on the neck of the vessel, represents a battle scene with several warriors. One of them is wearing a pilos and confronts a fighter with a Corinthian helmet, while two more warriors are represented behind them: one with an Attic helmet and the second with a petasos . On the opposite side a young warrior armed with a sword is fleeing from a bearded man pursuing him with a spear. Both are wearing a pilos . The interpretation of the frieze would need a long discussion, but it is just possible that it refers to episodes of the Iliad. The gilding looks very thick, as can be seen in the places where it is damaged by scratches and its aspect strongly suggests that it was produced by burnishing a relatively thick gold leaf on the perfectly cleaned and degreased surface of the silver. Around the eyes of the stag there are visible niello remains that look slightly silvery. This might be due to the «conservation», carried out when the rhyton was found. With all probability the vessel had been slightly heated, perhaps to reshape some small deformation of the silver. I received permission to take a tiny sample of the black material in the mouth of the stag, and both a SEM-EDS and a XRD analysis identified it as silver sulfide. In the nostrils of the stag there were very scant remains of the original niello, so that it had not been possible to collect a sample from there, however, at least visually, the material looked the same as the one on the eyes. The niello in the nostrils of the Trieste rhyton looked different from the niello on mouth, eyes, lashes, and on the top of the nose, and was darker and opaque.

The second rhyton belonging to the same collection is dated, like the first, to around 400 BC, and represents an adult deer (Fig. 2: 2 ), but has lost its horns (Ibid. P. 154).

Fig. 2. The rhyta decorated in niello technique

1 – Stag’s head rhyton, belonging to the Ortiz Collection, Geneva. Remains of niello can be seen in the corner of the left eye. 4th c. BC; 2 – Deer’s head rhyton, belonging to the Ortiz Collection, Geneva. Scant remains of niello can be recognized in the lashes, the mouth and the left nostril; 3 – Deer’s head rhyton, belonging to the Miho Museum, Japan. Some niello is visible in the lashes on both eyes. 4th c. BC; 4 – Stag’s head rhyton with gilded horns, Judy and Michael Steinhardt Collection (New York), now in the Metropolitan Museum (New York); 5 – Detail of the left eye of the stag. In the keying of the lower lashes some remains of niello can be seen

1, 2 – after: Ortiz , 1996; 3–5 – Photo A. Giumlia-Mair

Nevertheless, the empty receptacles for the insertion of the horns on top of the head testify that they were originally in place. The frieze on the neck depicts figures from the dionysiac thiasos : Dionysos with a thyrsos is the central figure, on his right stands a female figure, perhaps Ariadne, with a child, while around the neck several dancing satyrs complete the representation. The niello remains can be seen in the mouth groove, in the lashes, and in the nostrils, but only very little of it is left, so that no sample could be taken from this piece. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that also this rhyton was nielloed, like its companion in the same collection and the example at Trieste.

More examples of nielloed rhyta

I have been able to examine – only by means of optical devices with various magnification and a good galleryscope – two more examples of rhyta, dated to the same time period and, like the other examples, without a clear provenance, but allegedly coming from the Black Sea area.

The first is the rhyton in the Miho Museum in Japan, representing a young deer with just sprouting horns (Fig. 2: 3 ), as the bumps on the forehead indicate. The date seems to be the same of the previous pieces. The partly gilded frieze on the neck represents on the sides two centaurs with wild hair, wearing a panther skin as a cloak, and armed with a spiked spear, about to attack the central figure. The person depicted at the front of the neck is a sitting man, naked except for an animal skin on which he is sitting. Next to him a club is leaning on what looks like a laying dappled hind and he is wearing a wreath on the head. His attributes seem to identify him as Herakles on his hunt of the Ceryneian hind. The scene on the frieze seems to be conflating this myth with the following labor of Herakles: the hunt of the Erymanthian boar, during which he was attacked by drunken centaurs. Some remains of the niello that covered the upper lashes and an exiguous quantity inside the lower lashes can still be distinguished, but also this piece has been vigorously cleaned, probably by the people who found it.

The rhyton shaped like a stag’s head with gilded horns (Fig. 2: 4 ), belonging to the Judy and Michael Steinhardt Collection, New York, now lent to the Metropolitan Museum, New York, is dated to the 4th century BC. The scene was interpreted as representing the myth of Philoktetes and its details are partly gilded as on the other rhyta. The gilding also looks like a very thick gold foil applied on the silver.

The traces of the original niello are slightly more conspicuous on this specimen, especially in the lashes of the proper left eye of the stag, and certainly sufficient to establish the presence of this decorative material on the splendid vessel.

The examination of the two rhyta from Rozovets in the region of Plovdiv, now in the Archaeological Museum of Sofia, brought more knowledge and certainty about the existence of niello in Thrace as well. One of the rhyta, representing a deer (Fig. 3: 1 ), is very damaged and has visibly been repaired several times, certainly also by heating the piece. On this example no traces of niello could be seen, and even the gilding that certainly picked out the details of the frieze is lost, however the deep recesses cut on the surface of the vessel leave no doubt that they were originally filled with some substance that, from the examination and comparison with the other examples from this vast area, can only have been niello.

Fig. 3. The rhyta from Rosovets decorated in niello technique. Photo A. Giumlia-Mair

1 – Heavily damaged rhyton A, now in the Archaeological Museum in. Sofia, Bulgaria. Corrosion and restoration removed all traces of gilding and niello, but the keying indicates that originally some niello was applied around the eyes and on nose and mouth; 2 – Well-preserved rhyton B, now in the Archaeological Museum in Sofia, Bulgaria. Some niello is visible in the nostrils, around the eyes and in the lashes

The second rhyton from Rozovets, in the shape of a young deer with sprouting horns and a frieze representing griffins tearing a horse or a bull (Fig. 3: 2 ) is in a much better condition, except for the fact that the niello has been removed almost completely here as well. Luckily, some niello is still clearly visible in the nostrils, and possibly also in the mouth and the lashes. The gilding presents the same compact look of the previously discussed specimens.

The optical examination gave certainty about the existence of this material on many pieces broadly dated to the same period, however it would be important to ascertain the exact nature of the niello, i. e. which kind of sulfide had been employed for■ defin-ing the eyes, nose and mouth of the animals represented on the rhytons.

Conclusions

After the examination of various examples of rhyta from the Black Sea regions, we know that in the 5th–4th century BC there were silversmiths in workshops of the towns around this area, who were producing wonderful objects decorated with niello. Why was this tradition limited to this zone and did not spread out earlier? From the texts of the Greek alchemists ( Berthelot , 1967) we know that the transformation of metals such as copper and silver into a black sulfide by mixing them in a crucible with sulfur was known already very early. Why did it appear much later, half a millennium later, in Rome?

In the Mediterranean areas metal sulfides were known but had a negative connotation. The process of transforming metals into sulfides was considered a kind of «kill-ing of metal», because the copper or silver involved in the operation lost all their characteristic properties, such as color, sheen, and malleability, and became black and fragile. The process itself was employed as some kind of purification of copper and silver, because it eliminated all impurities and trace elements such as arsenic, lead, antimony, zinc and tin both when the metal was broken down to a sulfide and when it was «revived» i. e., re-heated to turn it again into a shiny and malleable metal. From the texts of the Greek alchemists, we know that the process of producing metal sulfides was called «melanosis» – the blackening. These operations generated a bad smell, that reminded the metalworkers of decay and rottenness. For this reason, black metal sulfides were considered dead matter and putrefaction that had to be eliminated in the purifying fire. This was certainly the reason why this material was not employed as decoration until Roman times, except in the regions around the Black Sea, where, quite evidently, there was a widespread tradition of the use of early niello for the wonderful rhyta found nowadays in 4th century BC graves. It would be interesting to research, if the rhyta decorated with niello were only employed for funerary use.

Список литературы On the origins of niello

- Маразов И., 1978. Ритоните в древна Тракия. София: Български художник. 180 с.

- Berthelot M., 1967. Collection des anciens Alchimistes Grecs. Vol. 1, 2. Osnabrück: Zeller. 284 + 477 p.

- Bolla M., 1999. Il «tesoro» di Isola Rizza: osservazioni in occasione del restauro, Quaderni ticinesi di numismatica e antichità classiche, Vol. XXVIII. P. 275–303.

- Dennis J. R., 1979. Niello: a technical study // Papers presented by the Trainers of the Art Conservation Training Programs Conference, Fogg Art Museum. Harvard: Harvard University. P. 83–95.

- Dörig J., 1987. Les trésors d’orfévrerie thrace. Roma: Bretschneider. 32 p. (Rivista di Archeologia. Supplementi; 3.)

- Giumlia-Mair A., 1996. Das Krokodil und Amenemhat III aus el-Faiyum // Antike Welt. No. 4. P. 313–321, 340.

- Giumlia-Mair A., 1997. Early Instances of Shakudo-type Alloys in the West // Bulletin of the Metals Museum. Vol 27. P. 3–15.

- Giumlia-Mair A., 1998. Hellenistic Niello // Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on the Beginnin of the Use of Metals and alloys (BUMA IV) / Ed. H. Kimura. The Japan Institute of Metals. P. 109–114.

- Giumlia-Mair A., 2000. Solfuri metallici su oro, argento e leghe a base di rame // 6a giornata Le scienze della terra e l’archeometria (Este, Museo Nazionale Atestino, 26–27 febbraio 1999) / Eds.: C. D’Amico et C. Tampellini. Este. P. 135–142.

- Giumlia-Mair A., 2002. Argento: il metallo della luna // Le Arti di Efesto, Capolavori in metallo dalla Magna Grecia / Eds.: A. Giumlia-Mair, M. Rubinich. Trieste. P. 123–132.

- Giumlia-Mair A., 2013. Development of artificial black patina on Mycenaean metal finds // Surface Engineering. Vol. 29. Iss. 2. P. 98–106.

- Giumlia-Mair A., Craddock P., 1993. Das schwarze Gold der Alchimisten, Mainz: Zabern Verlag. 185 S.

- Giumlia-Mair A., Kanta A., 2021. The Kuwano Sword from the Fetish Shrine at Knossos // Proceedings of the 5th International Conference «Archaeometallurgy in Europe» (19–21 June 2019, Miskolc, Hungary) / Eds.: B. Török, A. Giumlia-Mair. Drémil-Lafage: Èditions Mergoil. P. 291–300.

- Giumlia-Mair A., La Niece S., 1998. Early Niello Decoration on the Silver Rhyton in the Trieste Museum // The Art of the Greek Goldsmith / Ed. D. Williams. London: British Museum Publications. P. 139–145.

- Giumlia-Mair A., Lehr M., 2003. Experimental reproduction of artificially patinated alloys identified in ancient Egyptian, Palaestinian, Mycenaean and Roman objects // Metodologie ed esperienze fra verifica, riproduzione, comunicazione e simulazione: atti del convegno (13–15 settembre 2001) / Eds.: P. Bellintani, L. Moser. Trento: Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Servizio Beni Culturali. P. 291–310.

- Giumlia-Mair A., Quirke S., 1997. Black Copper in Bronze Age Egypt // Revue d’Égyptologie. 48. P. 95–108.

- Giumlia-Mair A., Riederer J., 1998. Das tauschierte Krummschwert in der Ägyptischen Sammlung München // Berliner Beiträge zur Archäometrie. Bd. 15. S. 91–94.

- La Niece S., 1983. Niello, an historical and technical survey // Antiquaries Journal. Vol. 63. Iss. II. P. 279–297.

- Maryon H., 1954. Metalwork and Enamelling – a practical treatise on gold and silversmiths’s work and their allied crafts. London: Hassell Street Press. 392 p.

- Moss A. A., 1953. Niello // Studies in Conservation. Vol. 1. Iss. 2. P. 49–62.

- Ortiz G., 1996. In Pursuit of the Absolute Art of the Ancient World: The G. Ortiz Collection. Berne: Benteli Publishers. 1 vol.

- Pfrommer M., 1983. Italien – Makedonien – Kleinasien. Interdependenzen spätklassischer und frühhellenistischer Toreutik // Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. 98. P. 235–285.

- Puschi A., Winter F., 1902. Silbernes Trinkhorn aus Tarent in Triest, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien. V. S. 112–127.

- Simon E., 1967. Boreas und Oreithyia auf dem silbernen Rhyton in Triest // Antike und Abendland. Bd. 13. S. 101–126.