On the question of studying the role of social capital under the conditions of the socio-economic crisis

Автор: Afanasev Dmitrii Vladimirovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 4 (40) т.8, 2015 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The concept of social capital has gained considerable popularity in the social sciences, as well as in practical politics on a national and international scale. Its heuristic potential is confirmed by numerous studies demonstrating the positive impact of the level and types of social capital on a wide range of economic, social and political phenomena, and especially the use of the concept of social capital to study economic growth and development issues. However, there is no universally accepted definition of social capital, and there is no unanimous opinion concerning the ways of measuring it. The paper contains a review of the current status of the theoretical field of the concept; it shows that researchers from different countries are interested in the impact of social capital on economic growth and development at the regional level. Specific comparative studies in different countries and regions strongly support the presence of a correlation that proves social capital is one of the powerful driving forces of development...

Social capital, economic growth, crisis, regional studies

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223755

IDR: 147223755 | УДК: 316.3 | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2015.4.40.6

Текст научной статьи On the question of studying the role of social capital under the conditions of the socio-economic crisis

Social capital represents one of the most powerful and popular metaphors in current social science research. In recent years social capital has become a key concept in academic theories and research, and a powerful basis for making policy decisions that are intended to shape everyday practices in creating social integration. Broadly understood as referring to the community relations that affect personal interactions, social capital has been used to explain an immense range of phenomena, ranging from voting patterns to health to the economic success of countries. Hundreds of papers have appeared throughout the science literature arguing that social capital matters in understanding individual and group differences and further that successful public policy design needs to account for the effects of policy on social capital formation.

Several reasons were proposed for explaining such attention. They include the concern with the extremes of today’s individualism and the nostalgia for the lost unity in the past, the desire to re-introduce the regulatory and social aspects in the understanding of how society works; the desire for greater control over the modern society that is becoming more diverse and is experiencing rapid social change, including the fact that social capital allows the state to save on distributive economic policy at the expense of (less expensive) informal social relations.

However, this concept cannot be considered an established one. Academic discourse contains different viewpoints, approaches and expectations; this fact leads to a wider interpretation of social capital. And this, in turn, entails even a greater blurring of the concept that is already expressed not very clearly, up to the loss of its heuristic potential and turning it into a popular publicistic cliche.

The present paper, first, provides an overview of conceptual issues that form the basis of the studies of social capital. Second, it determines the fruitfulness of usage of the concept of social capital to study the issues of economic growth and development both at the macrolevel and at the level of individual regions. Third, we make several suggestions about how to empirically explore the role and importance of regional social capital in the conditions of the crisis.

Social capital: the concept, its historical development and variations

We will not consider some occasional and rather metaphorical references to social capital in earlier works (L. Hanifan, D. Jacobs, G. Laurie1), but we note the fundamental contribution that James Coleman, Robert Putnam and Pierre Bourdieu – the authors who represent the classic studies of social capital – made to the development of the concept of social capital. Coleman and Putnam, who highlighted values and networks, formed a “mainstream” theory of social capital. Bourdieu, who represents the critical aspect in this trio, put forward the issues of inequality and social justice2.

Table 1. Number of publications with key words “social capital” according to the Web of Science data (1994–2013)

Year of publication Number of publications 2014 1107 2013 1063 2012 1025 2011 1024 2010 959 2009 872 2008 740 2007 641 2006 514 2005 441 2004 223 2003 217 2002 182 2001 170 2000 113 1999 102 1998 89 1996 25 1995 22 1994 10 Source of calculations: Web of Science. Available at:

Currently, the literature on social capital is extremely vast and it continues to increase (tab. 1) . Numerous researchers representing different disciplines have contributed to our current understanding of the prerequisites and consequences of social capital.

Defninitions of cocial capital

The term “social capital” has spread throughout the social sciences and has spawned a huge literature that runs across disciplines. Despite the immense amount of research on it, however, the definition of social capital has remained elusive. Moreover, it has been argued that it is unreasonable and old-fashioned to believe that in general it is possible to develop a unified concept of social capital which would explain and predict diverse and complex fields such as economics, politics, and social sphere, i.e. as a new Grand Theory. In the beginning of the century the criticism of ambiguity and contradiction of different definitions of the term “social capital” went so far that some researchers proposed to abandon the term altogether3. A new rise in the popularity of the concept is associated with its application to a new virtual reality of communications, i.e.

to the social media. From a historical perspective, one could argue that social capital is not a concept but a praxis, a code word used to federate disparate but interrelated research interests and to facilitate the crossfertilization of ideas across disciplinary boundaries. The success of social capital as a federating concept may result from the fact that no social science has managed to impose a narrow definition of the term that captures what different researchers mean by it within a discipline.

In order to illustrate this diversity, we will present several of the most influential definitions of social capital. Let us begin with Coleman, who defined social capital as follows: “...Social organization constitutes social capital, facilitating the achievement of goals that could not be achieved in its absence or can be achieved only at a higher cost” [23, p. 304]. And in another work: “It is not a single entity but a variety of different entities, with two elements in common: they all consist of some aspect of social structures, and they facilitate certain actions of actors – whether persons or corporate actors – within the structure” [2, p. 124].

R. Putnam and his colleagues provide a similar characterization: “...Social capital… refers to features of social organization, such as trust, norms, and networks that can improve the efficiency of society...” [49, p. 167]. In another well-known work [51] he emphasizes characteristics of social organization, including networks, norms and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation in the interests of the public goal.

Both definitions emphasize the beneficial effects social capital is assumed to have on social aggregates. According to these definitions, social capital is a type of positive group externality. Coleman’s definition suggests that the externality arises from social organization. Putnam’s definition emphasizes specific informal forms of social organization such as trust, norms and networks.

In his own definition of social capital Fukuyama argues that only certain shared norms and values should be regarded as social capital: “Social capital can be defined simply as the existence of a certain set of informal rules or norms shared among members of a group that permits cooperation among them. …The sharing of values and norms does not in itself produce social capital, because the values may be the wrong ones… The norms that produce social capital must substantively include virtues like truth-telling, the meeting of obligations, and reciprocity” [8, p. 30].

Other definitions characterize social capital not in terms of outcome but in terms of relations or interdependence between individuals. In later research, Putnam defines social capital as “...connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them” [52, p. 19].

E. Ostrom writes that “social capital is the shared knowledge, understandings, norms, rules, and expectations about patterns of interactions that groups of individuals bring to a recurrent activity” [45, p. 176].

Table 2. Various definitions of the term “social capital”

|

Author, publication date |

Defintions of the concept “social capital” |

|

Bourdieu, 1980 [20] |

Social relations that can act as a resource to obtain benefits |

|

Knack and Keefer, 1997 [36] |

Trust, norms of cooperation and membership in associations |

|

Narayan and Pritchett, 1999 [43] |

Quantity and quality of associational life and the related social norms |

|

Woolcock, 2001 [66] |

Social capital, unlike its other forms, is not the exclusive characteristic of an individual, rather, it describes the relationships between people in which the individual is involved |

|

Lin, 2001 [38] |

Resources embedded in social networks assessed and used by actors for actions |

|

Sobel, 2002 [56] |

Circumstances in which individuals can use membership in groups and networks to secure benefits |

|

Shikhirev, 2003 [11] |

Quality of social relationships, of which the key qualitative characteristic is ethical level |

|

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD: Cote, Healy, 2001) [44] |

Networks, norms, values and understandings that facilitate cooperation within or among groups |

|

World Bank, 2005 [24] |

Norms and networks facilitating collective action |

|

Polishchuk, 2010 [5] |

Capacity of a society or communities for self-organization and joint action |

Here is a list of popular definitions of social capital.

As this small sample shows, there remains significant variation of definitions, and this inevitably gives rise to the difficulties in measuring social capital and considerable controversy around this concept; and the number of disputes is ever increasing.

Without plunging into a detailed discussion of all the existing definitions of social capital, it is important to specify how we understand social capital exactly because there are so many of its diverse interpretations. We agree with the conclusions of Durlauf and Fafchamps who distinguish three main underlying ideas from almost all the definitions of social capital: “First, social capital generates (positive) externalities for members of a group. Second, these externalities are achieved through shared trust, norms, and values and their consequent effects on expectations and behavior. Third, shared trust, norms, and values arise from informal forms of organizations based on social networks and associations [266, p. 1644]. Thus, they argue that “the study of social capital is that of network-based processes that generate beneficial outcomes through norms and trust” [ibid.].

Although certain scientific works sometimes reduce social capital to its individual attributes or aspects (networks, trust or participation), one in isolation would probably not be considered social capital. Social capital refers to networks of social relations characterised by norms of trust and reciprocity.

Like physical capital (e.g., technology and tools) and human capital (e.g. education, talent and skills), social capital increases productivity of individuals and groups. Unlike physical capital, however, social capital does not wear out or devalue in the process of its use. Also, unlike physical capital, social capital is not exclusive and can be used by many people at a time. In this sense, social capital has many attributes of a “social good”.

The studies that identify and describe the role of social capital, have provided some convincing answers to the question about the popularity of social capital and interest in this subject.

The concept of social capital is based on the idea that social relationships and social norms can provide access to valuable resources that can improve well-being of man [28], family [43], communities [19] or even regions or countries [36]. The benefits of social capital are now well established both at the micro- and macro levels. One of the long-standing assertions in the literature is that social capital can facilitate the solution of collective action problems. In politics, the generalized trust and other civil attitudes allow citizens to unite their forces in social and political groups and enable them to unite in civil initiatives more easily. Having proved that the effects of social capital, no doubt, entail social benefits for individuals, the research thus reveals a direct link between certain aspects of social capital and large-scale results, such as economic growth [25; 30; 36], low crime rate [34; 61] and authorities that are more responsible to the society [49].

Despite all the controversy, research suggests that social capital is an intangible factor and resource that affects the economy, social welfare, the effectiveness of social programs and many other things. It is important for the quality of public services such as education, health care, health status, reproductive potential, public safety, and the quality of public services and public administration. Generalized trust in the social sphere makes life easier in a heterogeneous society and promotes tolerance and acceptance of differences. Life in multicultural societies is easier, happier and more confident if there is generalized trust [60]. There are fewer cases of expulsion from school among the children integrated into supportive social networks [22]; moreover, some studies have found a strong connection between mental and even physical health and involvement in networks [52; 53].

These various examples of the impact of social capital demonstrate the seeming inconsistency in the numerous studies of social capital. The sociological tradition of research on social capital seems to focus on a wide range of positive outcomes that social capital provides for a person or for individual groups. This approach is indeed very broad and includes diverse examples such as a network of diamond dealers, a network of concerned parents of schoolchildren and strong family relationships as a form of social capital. Such networks can be of benefit for individual network members and other individuals who are not their members (e.g., other parents at school); or, on the contrary, sometimes they can be so exclusive that the benefits become a kind of club benefits that exclude outsiders.

Types of social capital

Initially, social capital was viewed as a unidimensional construct, which produces exclusively positive results, but it is now generally acknowledged that there are different types of social capital and that it also has a “dark side”. Although it is shown that social capital enables and facilitates collective action, but society can have detrimental collective goals, and the presence of social capital may allow them to achieve these goals more easily. This has led to the conclusion that not only the level of social capital is important for society, but also its type. Not all types of social capital are considered benign, and only some aspects of social capital can have positive consequences for society as a whole.

In this regard, Putnam distinguished two types of social capital: bonding capital and bridging capital4. The latter can be defined as the connections of bonds that are formed on top of various social groups, while bonding social capital cements only homogenous groups.

According to Putnam, bridging social capital refers to social networks that bring together different people, and bonding social capital brings together similar people. This is an important distinction, because external effects for bridging groups will, most likely, be positive, while networks that are bonding (limited to certain social niches), are at greater risk of negative externalities.

This distinction in types of social capital was proposed by other researchers [29; 47; 63] who sometimes used different terminology, but pointed to the same underlying phenomena. For example, Granovetter introduced the useful distinction between strong and weak ties, arguing that the latter kind provides various benefits to its members, particularly in terms of job searches [31]. Weak ties allow for more efficient information flows and are therefore particularly beneficial for facilitating collective action. Polishchuk and Menyashev operate with the concepts of “open social capital”, “closed social capital”, “Olson-like” and “Putnam-like” groups, in fact, identifying them with the forms of capital distinguished by Putnam [3].

Beugelsdijk and Smulders [16] show that bridging social capital has a positive effect on growth, whereas bonding social capital has a negative effect on the degree of sociability outside the closed social circle. This result finds evidence for Fukuyama’s claim that “the strength of the family bond implies a certain weakness in ties between individuals not related to one another” [8, p. 103].

It should again be noted that any form of social interaction – whether it is bridging social capital or bonding social capital – provides benefits and advantages for atomized agents. Homogeneous bonding groups can also pursue positive goals, but there is a danger that they can sharpen and deepen social cleavages, especially in pluralistic societies fragmented because of the deeply rooted ethnic, racial, religious, etc. conflicts.

It is important that, unlike bonding social capital, bridging social capital has a greater (positive) impact on economic growth. Having said that, we do not claim that communication with one’s family and close friends is a bad activity in itself. The key point is the distinction between types of communication; investment in bridging social capital are better from the perspective of economic growth.

Some researchers [52; 57; 63] define the third component – linking social capital – describes connections with people in positions of power and is characterised by relations between those within a hierarchy where there are differing levels of power. It is good for accessing support, resources, and ideas from formal institutions and leaders in positions of power outside the range of the individual’s circle of communication and which can distribute resources that are often rare. Linking social capital is different from bonding and bridging in that it is concerned with relations between people who are not on an equal footing. Thus, the nature of relationships in this type of social capital is vertical – it connects people at different levels of power. Bridging and bonding relationships (or horizontal networks) are also called trust networks, while linking (or vertical) relationship forms power networks.

Social capital, economic growth and development

Western and Russian researchers [6; 15; 36; 66] agree that in the realities of modern economic development the social aspect of the category “capital” is becoming increasingly important. The idea of social capital sits awkwardly in contemporary economic thinking. Even though it has a powerful, intuitive appeal, it has proven hard to track as an economic good. Among other things, it is fiendishly difficult to measure. This is not because of a recognised paucity of data, but because we do not quite know what we should be measuring. Comprising different types of relationships and engagements, the components of social capital are many and varied and, in many instances, intangible.

Attention to social capital is increasing due to the recognition that his absence is one of the main obstacles to economic development. In general, the conclusion that “social institutions have economic value” was first made by R. Putnam and D. Helliwell in their analysis of activities of enterprises in Italy in the 1960s – 1970s [50]. A significant part of current interest in social capital stems from the later classical book by Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti [49], who argued that Northern Italy is growing faster than Southern Italy, by virtue of greater social capital endowements of the former, measured by membership in groups and clubs. The researchers found that a high level of “associative” life, trust and norms of reciprocity and civic cooperation strongly correlate with income per capita in the region. Subsequent criticism has identified the insufficient validity and strictness of straightforward conclusions of the authors and doubtless positive external effects of social capital on the economy.

Knack and Keefer were initiators of studying the impact of social capital on economic growth in the empirical analysis [36]. They built a model that links economic growth of countries to the level of trust, ethic norms and membership in associations. They show that trust and civic cooperation have a significant impact on economic performance; and, moreover, not all the elements of the minimal definition of social capital are significant – in particular, participation in networks has little to do with trust and economic performance.

Woolcock [63] presented a broad conceptual analysis of the role of social capital in the development of society and economy; Dasgupta and Sergaldin [25, p. 15], and Grootaert and van Bastelaer [32] made a list of effects of social capital on economic development. Whiteley [62] investigated the relationship between social capital and economic growth in a sample of thirty-four countries for the period from 1970 to 1992 in the framework of the modified neoclassical model of economic growth. In general, these results indicate that social capital influences growth, and this influence is at least as strong as that of human capital, the former center of attention of many works on the growth theory.

-

S. Beugelsdijk and S. Smulders [16], analyzing the properties of the model, suggest that the link between economic growth and social capital depends on the

internal characteristics of the system and may have different directions for different societies and periods of development, namely, for more developed and less developed countries. The charasteristics of the current status can be identified by empirical analysis.

R. Menyashev and L. Polishchuk carried out a pioneering and unique research on the effect of social capital of Russia’s regions on economic performance. On the basis of the data obtained by the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM) within the framework of the national survey, they carried out the factor and regression analysis and came to a conclusion that “despite the doubts about the ability of the Russian society to become an independent driving force of the country’s development, social capital in the Russian context provides a tangible economic return, primarily through the increased accountability of authorities” [3].

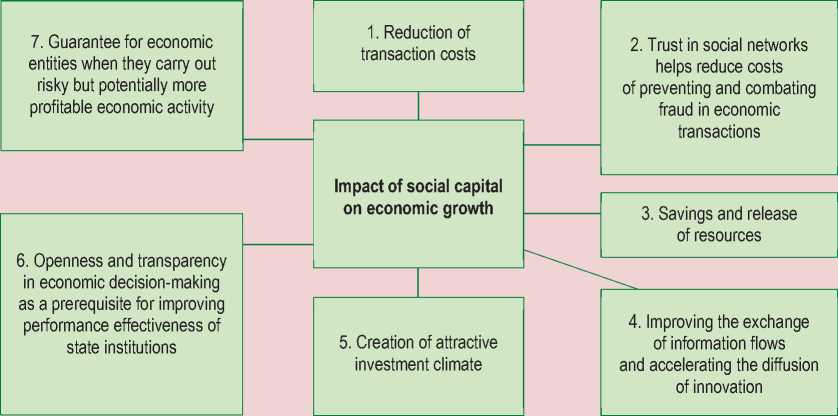

Figure 1. Impact of social capital on economic growth

-

T. Shapovalova systematized positive effects of social capital on economic growth [10].

Although quantitative measures used by different authors to prove the thesis about the impact of social capital on economic growth and development continue to cause controversy, one can summarize the qualitative findings relating to the subject matter of the controversy.

Social capital, first of all, reduces transaction costs of:

– searching for information and verification of counterparties;

– coordination (execution of formal bureaucratic procedures, contracts, etc.);

– control and coercion of counterparties to comply with the obligations for state regulation (because social capital is associated with the expectations that other economic agents will meet their obligations without application of sanctions).

Thus, it is possible to speak of the cheaper cost of negotiations, the facilitation of personalized informal interaction between the participants of economic relations, the potential of self-regulation of economic activity, the reduction of costs on the maintenance of state institutions and other implicit costs that society bears.

Social capital facilitates access of its owners to the resources gained (created, redistributed) in the social network. The results are as follows:

– cheap loans, greater access to information, innovation, better jobs, etc.;

– decrease of vulnerability, assistance in case of failure, crisis and other force majeure.

General effects of social capital at the level of society are as follows:

– compensation of the weakness of the institutional environment of economic activities, ineffectiveness of formal institutions;

– improvement of socio-political stability and quality of governance;

– general improvement of the social situation, enhanced possibility of cooperation, collective action for the common goal;

– positive social well-being of individuals, the lowering of the risk threshold for decision making in conditions of uncertainty.

Social capital and crises

So far, the impact of the crisis on social capital and the reverse impact of social capital on the course of the crisis has not been the subject of systematic study, although scientific literature considers occasional and fragmentary research on different aspects of the relationship of these two concepts.

First of all, here we speak about the cyclical financial and economic crises, but we also need to talk about structural local or national crises associated with the depreciation of certain industries and sectors of economy and with the crisis of relevant national or local communities (regions, cities and villages).

Exploring the impact of the crises of the first type (and if the hypothesis is correct, we see a direct and strong correlation between economic crisis and social capital), we can hope to find regularities in the dynamics of social capital between 2006 and 2015, which correlated with the dynamics of economic indicators.

Theoretically, in this connection, a question arises concerning what happens to a country after a major economic trauma, such as the current crisis: does its social structure begin to burst at the seams or, on the contrary, people are uniting to cope with misfortunes they are going through? Do people in a crisis situation become more dependent on their families and friends as a means of overcoming their economic difficulties than they used to be before the crisis, and how actively do they participate in civil actions and political life, or they just lose faith in political participation? Do they shift the responsibility for the crisis on the government or build strategies to respond to the crisis in their own networks? These issues stem from an important and urgent contemporary social issue: they are a starting point for research into the social consequences of economic crisis.

On the one hand, it can be assumed that economic crisis is accompanied by the crisis of trust. In this sense, crisis destroys social capital. And this process starts a vicious circle, since the crisis of social capital, in turn, becomes an obstacle to the recovery from economic crisis with the help of cooperation, coordination and joint action. Thus, we can formulate a hypothesis that crisis conditions can threaten the social fabric of the country due to the growth of distrust. But it is possible that if the recession has really affected the level of trust, then it lowered it to a considerable, but not to a catastrophic, degree.

At the same time it is not enough just to show that economic crisis leads to a fall in the indicators of social capital. It is necessary, first, to prove that it is not part of other long-term societal changes and second, to figure out exactly what type of social capital we seak of.

Thus, it is possible to put forward some more hypotheses.

-

a. A higher level of social capital facilitates the overcoming of the crisis. Regions with a higher level of social capital ceteris paribus recover from the crisis faster.

-

b. Bonding social capital contributes to survival in the short term by transferring resources across the networks of closed groups that could be confirmed by the identified increase in family and kinship ties, and by the weakening of social and political activity, etc.

-

c. Bridging capital contributes to overcoming the crisis in the long term, because it promotes the inter-network search for ways out of the crisis and for resources.

In addition, it is not enough to consider only the ways in which economic crisis may have a negative impact on social capital. From the point of view of social capital, the impact of crisis on individuals and society can be not only negative but also positive.

We can assume that social capital is a protective factor in the period of economic crisis. Social capital and social networks may represent a network that offers protection from adverse effects of rapid macroeconomic changes. This makes us think of whether and to what extent social capital can act as a means of compensation for the damage caused by greed, selfishness, short-sightedness, or outright stupidity of politicians, bankers, financial speculators, etc.

Sociologists and economists should also consider how the existing stock of social capital can help people to cope with the severity of the crisis and how this process may over time even help replenish the social capital of the country and the region. So, J o hannesson, Skaptad o ttir and Benediktsson [35, p. 4] show that the priority in determining a person’s ability to cope with economic crisis is the prevalence of social networks, the ability to innovate and a strong sense of both individual and social identity, or in other words, social capital.

It is possible that individual and collective attempts to resolve the crisis can prevent the decline of social capital. In some cases, the period of crisis may lead to the strengthening of social cohesion and even generate new relationships that improve the general social capital when communities are finding innovative ways of handling their problems.

In our analysis we attach importance to factors such as the level of social capital that changes during the crisis, and the greater or lesser role of social capital during and after the financial and economic crisis, the role that is manifest in civic activity and politics.

Future research should pay attention to the fact whether frequent appeals to social capital (and civil society) in the crisis discourse are a disguised attempt by the government to pass on to the society some of social expenses under the shortage of public resources and decline of its effectiveness.

Scientific research has not given due attention to the impact of structural crises – the second type of crises which affect single-industry cities and regions – on social capital (and vice versa: the impact of social capital on the course of the crisis), the studies are fragmentary, although the importance of the topic itself does not cause any doubt.

Baerenholdt and Aarsaether use the concept of social capital in connection with their concept of a “coping strategy”5 [14] of the region, the strategy of responding to crisis, which is based on the existing social capital and, at the same time, contributes to its development. The work of J o hannesson, Skaptad o ttir and Benediktsson also links the concept of social capital to the capacity of the region to get out of the crisis through coping strategies, demonstrating the power of this approach on the example of Iceland’s regions [35].

Perhaps the most notable study in this direction is the work of Sean Safford, built on the comparison of the stories of two American single-industry towns caught in the crisis. Safford, like other researchers, was looking for an answer to the question why some cities within the U.S. Rust Belt experienced a dramatic restructuring of their economy, and then flourished during the economic boom of the 1990s – early 2000s, while others failed. The author tries to answer this question by exploring two middle-sized industrial cities – Allentown, Pennsylvania and Youngstown, Ohio, when they faced a collapse of their main industry – metallurgy [54; 55]. Safford argues that their different fate was a direct result of different evolutions of social networks in the two cities. He comes to the conclusion that a community that is facing a severe economic crisis, profits the most from the layers of independent associations that connect at key points, build critical bridges over the social, economic and geographic divisions within the community. Through a brilliant network analysis Safford shows that the developed networks of the bridging type in one of the cities contributed to a more rapid and successful recovery from the crisis as opposed to the networks of the bonding type, which contribute more to survival and economic exchange.

The relevance of such studies focusing on the dynamic role of local social systems and structures in the response of the community to the impact of economic crisis is doubtless because they offer a viable alternative to purely economic development strategies in times of crisis.

Regional development and social capital

Scientific research has quickly turned its attention to the following issue: national indicators of the level and type of social capital hide significant variations at the regional level. On the one hand, regional studies help identify correlations and dependencies on broad representative samples, on the other hand – to empirically test the hypotheses about the contribution of social capital to economic growth and development on the basis of regional differences in the types and levels of social capital.

It should be recalled that the very concept of social capital owes its existence in many respects to Putnam and Helliwell who carried out a comparative study of the regions of Northern and Southern Italy. S. Panebianco used similar indicators and applied their research findings to the regions of Germany [46].

The majority of subsequent empirical studies show positive effects of social capital and its components on regional development. Knack and Keefer, La Porta and colleagues, Zak and Knack use the data of the World Values Survey for different regions and countries to show that differences in trust – measured by the question “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” – have a significant impact on national growth rates [36; 37; 67].

Beugelsdijk and van Schaik, and Tabellini presented similar results for economic growth in European regions [17; 58]. Tabellini used additional variables relevant to post-material values, and also discovered a positive relationship to regional growth. Algan and Cahuc [12] calculated the impact of trust – a component of social capital – on the change in the index of per capita income across countries in 1935–2000. Callois and Schmitt [21] carried out an econometric analysis of the data on rural areas of France; they used indirect indicators of social capital and found positive influence of all forms of social capital on economic growth, and complementarity of bridging and bonding types of social capital.

Blume and Sack showed differences in the patterns of social capital that influence the pace and nature of economic growth on the example of the regions of Western Germany [18].

Thus, empirical testing on the material of Western countries confirms the earlier hypotheses of a positive correlation between regional social capital and economic growth. At the same time, it is not yet possible to make an equally confident conclusion about the regions of the countries that are at a lower stage of economic development. As for the post-Communist countries, including Russia, the relevant data are fragmentary and they cannot be compared properly.

A paper by J. Dzialek [27] describes spatial patterns of social capital in Poland and focuses in particular on its relationship to economic development in the context of experience of the post-Communist countries of Central Europe. The author tried to answer two main research questions: how diversified the resources of social capital in Polish regions are and if the model of social capital can be used to explain the differences in the pace of economic growth in Polish regions.

Zalek has shown, first, that social capital resources in Poland are characterized by high spatial differentiation only partially related to previous ways of development and historical heritage of the regions. Second, he has found out that this differentiation has an impact on the current regional economic development dynamics, i.e. the regions with a higher level of social capital, especially bridging social capital, can develop faster, which is similar to the trends revealed in the course of research conducted in the regions of Western Europe.

However, the overall resources of social capital in Poland’s regions are relatively low, which makes the contribution of social capital to economic development significantly weaker than in developed countries.

Initial attempts to apply the concept of social capital to the research on Russia’s regions were made in the beginning of the century.

C. Marsh in his several papers [40; 41; 42] proposed an original methodology for measuring the index of social capital in some regions of Russia. The index is formed by indicators such as “voter turnout”, “newspaper publishing” and “membership in clubs and cultural associations” in a given region of the Russian Federation. Marsh has found a correlation between the civic community index and the index of democratization. Regions with a higher civic community index demonstrate a higher index of democratization and vice versa. However, the set of indicators used by March, can hardly be called generally accepted, that is why its data are poorly comparable with those of other researchers; and the proposed indicators of social capital must be considered very critically.

J. Twigg [59] proposes a different scale for comparative measurement of social capital in Russia’s regions. Since there was no data that would directly characterize social capital in Russia and one of its features, namely, trust, she used statistical indicators that, in her opinion, act as

“substitutes” for direct indicators: “crime rate”, “culture”, “family” and “work”, and six additional indicators of social capital. On this basis she also found out a significant differentiation of the regions by level of social capital. However, her extremely broad interpretation of social capital diminishes the analytical value of the findings and makes the data incomparable with those obtained with the use of conventional approaches.

The above-mentioned study by R. Menyashev and L. Polishchuk started out from the apparent pattern of significant differences in the level of social capital in different regions and within them [5].

E. Trubekhina used the methodology of Beugelsdijk and Smulders [16] and the data of “Georating” by FOM and economic statistics (GRP per capita and the turnover of small business per capita in the region); she has found a positive correlation between the participation in various groups and organizations (like an aspect of open social capital) and the value of GRP per capita. She has also found out that the development of small business depends to a great degree not only on the open, but also on the closed type of social capital. The indicators of subjective trust proved to be insignificant [7].

Of course, these data on Russian regions are unique and fragmented. Realizing this fact, researchers write that “it is also important to find a more convincing evidence of a causal link between social capital and development by choosing suitable instrumental variables” [3, p. 169].

Thus, there are several obstacles from the viewpoint of the task to study comprehensively the relationships between social capital in Russia’s regions and other social and economic characteristics. These obstacles are as follows: relatively limited and non-diversified sets of variables used to describe a wide range of different types of social capital; the use of variables that describe possible effects of the presence or absence of social capital (for example, crime rate and voter turnout) rather than social capital itself; and the neglect of economic and human capital in the models of influence of social capital on economic growth.

Still the question remains why some locations (for instance, regional industrial systems, industrial clusters, urban areas) are more conducive to the development and strengthening of civic cooperation and, consequently, are endowed with more resources of social capital.

Thus, the first step for analysis is to study the resources and types of social capital in Russia’s regions. Only after that can we consider whether it has a positive or negative impact, and test the hypotheses about the relationship of this concept and economic growth and about the nature of this relationship.

Prerequisites for the research on social capital in the regions

So, Russia has not carried out a comprehensive assessment of social capital that would give reasonable conclusions about its level, types, role in economic and social development, the dynamics of change and contribution to anti-crisis strategies. Social capital has not been studied in various aspects and at different levels (time or geographical; belonging to social strata and occupational groups, etc.). As a consequence, there is no database that would combine the features and characteristics of social capital for the purposes of its study and management in general, and in the spatial perspective, in terms of regions. Not less scarce are the ways and means needed for an unambiguous measurement of capital and definition of mechanisms and tools for its development. All this shows that the issue concerning the research into the role of social capital for socio-economic development of a region and individual locations in Russia remains open and unresolved.

Список литературы On the question of studying the role of social capital under the conditions of the socio-economic crisis

- Afanas’ev D.V. Sotsial’nyi kapital: kontseptual’nye istoki i politicheskoe izmerenie . Sotsial’nyi kapital kak resurs modernizatsii v regione: problemy formirovaniya i izmereniya: materialy Mezhregional’noi nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii, g. Cherepovets, 16-17 oktyabrya 2012 g. . In 2 parts. Part 1. Pp. 11-22.

- Coleman J. Kapital sotsial’nyi i chelovecheskii . Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost’ , 2001, no. 3, pp. 122-139.

- Menyashev R.Sh., Polishchuk L.I. Ekonomicheskaya otdacha na sotsial’nyi kapital: o chem govoryat rossiiskie dannye? . XI Mezhunarodnaya nauchnaya konferentsiya po problemam razvitiya ekonomiki i obshchestva . Moscow: Izd. dom Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki, 2011. Vol. 2. Pp. 159-170.

- Natkhov T.V. Sotsial’nyi kapital i obrazovanie . Voprosy obrazovaniya , 2012, no. 2, pp. 63-67.

- Polishchuk L. Sotsial’nyi kapital v Rossii: izmerenie, analiz, otsenka vliyaniya . Available at: http://www.liberal.ru/articles/5265 (accessed May 10, 2015).

- Polishchuk L., Menyashev R.Sh. Ekonomicheskoe znachenie sotsial’nogo kapitala . Voprosy ekonomiki , 2011, no. 12, pp. 46-65.

- Trubekhina I.E. Sotsial’nyi kapital i ekonomicheskoe razvitie v regionakh Rossii . INEM -2012. Trudy II Vserossiiskoi (s mezhdunarodnym uchastiem) nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii v sfere innovatsii, ekonomiki i menedzhmenta. Tomsk, 24 apr. 2012 . Tomsk: Tomskii politekh. un-t, 2012. Pp. 357-361.

- Fukuyama F. Velikii razryv . Moscow: AST, 2008.

- Fukuyama F. Doverie: sotsial’nye dobrodeteli i put’ k protsvetaniyu . Moscow: AST; ZAO NPP “Ermak”, 2004.

- Shapovalova T.V. Vpliv sotsial’nogo kapitalu na ekonomichne zrostannya . Ekonomichnii analiz: zb. nauk. prats’ , 2013, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 167-175.

- Shikhirev P.N. Priroda sotsial’nogo kapitala: sotsial’no-psikhologicheskii podkhod . Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost’ , 2003, no. 2, pp. 17-32.

- Algan Y., Cahuc P. Inherited Trust and Growth. American Economic Review, 2010, vol. 100, no. 5, pp. 60-92.

- Arrow K. Observations on Social Capital. Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective. Ed. by P. Dasgupta, I. Seragilden. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2000. Pp. 3-5.

- Baerenholdt J., Aarsaether N. Coping Strategies, Social Capital and Space. European Urban and Regional Studies, 2002, no. 9 (2), pp. 151-161.

- Bebbington A., Guggenheim S., Olson B., Woolcock M. Exploring Social Capital Debates at the World Bank. Journal of Development Studies, 2004, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 33-64.

- Beugelsdijk S., Smulders S. Bonding and Bridging Social Capital and Economic Growth. Center Discussion Paper, 2009, no. 27, pp. 1-39.

- Beugelsdijk J., van Schaik T. Differences in Social Capital Between 54 Western European Regions. Regional Studies, 2005, no. 39, pp. 1053-1064.

- Blume L., Sack D. Patterns of Social Capital in West German Regions. European Urban and Regional Studies, 2008, no. 15, pp. 229-248.

- Bowles S., Gintis H. Social Capital and Community Governance. Economic Journal, 2002, vol. 112, no. 483, pp. 419-436.

- Bourdieu P. The Forms of Capital. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Ed. by J. Richardson. New York, Greenwood, 1986. Pp. 241-258.

- Callois J.-M., Schmitt B. The Role of Social Capital Components on Local Economic Growth: Local Cohesion and Openness in French Rural Areas. Review of Agricultural and Environmental Studies, 2009, no. 90 (3), pp. 257-286.

- Coleman J., Hoffer T. Public and Private High Schools: The Impact of Communities. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

- Coleman J. The Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 1993.

- Community Driven Development and Social Capital: Designing a Baseline Survey in the Philippines. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2005.

- Dasgupta P., Sergaldin I. Social Capital: a Multifaceted Perspective. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2000.

- Durlauf S.N., Fafchamps M. Social Capital. Handbook of Economic Growth. Ed. by P. Aghion, S. Durlauf. Elsevier, 2005. Vol. 1b. Pp. 1639-1699.

- Dzialek J. Is Social Capital Useful for Explaining Economic Development in Polish Regions? Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 2014, vol. 96, no. 2, pp. 177-193.

- Fafchamps M., Minten B. Property Rights in Flea Market Economy. Economic Development and Cultural Chance, 2001, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 229-267.

- Fedderke J.W., De Kadt R.H.J., Luiz J. Economic Growth and Social Capital. Theory and Society, 1999, no. 28, pp. 709-745.

- Fukuyama F. Trust: the Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: The Free Press, 1995.

- Granovetter V.S. The Strength of Week Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 1973, vol. 78, no. 6, pp. 1360-1380.

- Grootaert C, van Bastelaer Т. Understanding and Measuring Social Capital. A Multidisciplinary Tool for Practitioners. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2002.

- Hanifan L.J. The Rural School Community Centre. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 1916, vol. 67, pp. 130-138.

- Jacobs J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961.

- Jóhannesson G., Skaptadóttir U., Benediktsson K. Coping with Social Capital? The Cultural Economy of Tourism in the North. Sociologia Ruralis, 2003, no. 43 (1), pp. 3-16.

- Knack S., Keefer P. Does Social Capital Have an Economic Pay-Off? A Cross Country Investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1997, no. 112 (4), pp. 1251-1288.

- La Porta R., Lopez-de-Silanes F., Schleifer A., Vishny R. W. Trust in Large Organizations. American Economic Review, 1997, vol. 87, pp. 333-338.

- Lin N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Loury G. A Dynamic Theory of Racial Income Differences. Women, Minorities and Employment Discrimination. Ed. by P. Wallace. Lexington Books, 1977. Pp. 153-186.

- Marsh C. Making Russian Democracy Work. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2000.

- Marsh C. Social Capital and Democracy in Russia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 2000, no. 33, pp. 183-199.

- Marsh C. Social Capital and Grassroots Democracy in Russia’s Regions: Evidence from the 1999-2001 Gubernatorial Elections. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratisation, 2002, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 19-36.

- Narayan D., Pritchett L. Cents and Sociability: Household Income and Social Capital in Rural Tanzania. American Sociological Review, 1997, no. 9, pp. 871-897.

- Healy T., Côté S. OECD. The Well-Being of Nations. The Role of Human and Social Capital. Paris, 2001.

- Ostrom E. Social Capital: Fad or a Fundamental Concept? Social Capital, a Multifaceted Perspective. Ed. by P. Dasgupta, I. Serageldin. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2000.

- Panebianco S. The Impact of Social Capital on Regional Economic Development. ACSP Congress. Lovanio, 2003.

- Paxton P. Is Social Capital Declining in United States? A Multiple Indicator Assesment. The American Journal of Sociology, 1999, vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 88-127.

- Putnam R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Tradition in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Putnam R.D., Leonardi R., Nanetti R.Y. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Putnam R., Helliwell J. Economic Growth and Social Capital in Italy. Eastern Economic Journal, 1995, no. 21 (3), pp. 295-307.

- Putnam R. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. Journal of Democracy, 1995, January, pp. 65-78.

- Putnam R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

- Rose R. How Much Does Social Capital Add to Individual Health? A Survey Study of Russians. Social Science & Medicine, 2000, vol. 51, no. 9, pp. 1421-1435.

- Safford S. Why the Garden Club Couldn’t Save Youngstown: Civic Infrastructure and Mobilization in Economic Crises. Working Paper. MIT Industrial Performance Center, 2004.

- Safford S. Why the Garden Club Couldn’t Save Youngstown: The Transformation of the Rust Belt. Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Sobel J. Can We Trust Social Capital? Journal of Economic Literature, 2002, vol. 40, pp. 139-154.

- Szreter S., Woolcock M. Health by Association? Social Capital, Social Theory, and the Political Economy of Public Health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 2004, vol. 33, pp. 650-667.

- Tabellini G. Culture and Institutions: Economic Development in the Regions of Europe. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2010, vol. 8 (4), pp. 677-716.

- Twigg J.L., Schecter K. Social Capital. Social Capital and Social Cohesion in Post-Soviet Russia. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2003. Рp. 168-188.

- Uslaner E. The Moral Foundations of Trust. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Wilson W.J. The Truly Disadvantaged: the Inner City, the Underclass and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Whiteley P. Economic Growth and Social Capital. Political Studies, 2000, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 443-466.

- Woolcock M. Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework. Theory and Society, 1998, no. 27 (2), pp. 151-208.

- Woolcock M., Narayan D. Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory Research and Policy. World Bank Research Observer, 2000, no. 15 (2), pp. 225-251.

- Woolcock M. Exploring Social Capital Debates at the World Bank. Journal of Development Studies, 2004, no. 40 (5), pp. 33-64.

- Woolcock M. The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcomes. Isuma: Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2001, vol. 2:1, pp. 1-17.

- Zak P.J., Knack S. Trust and Growth. Economic Journal, 2001, vol. 111, pp. 295-321.

- Web of Science. Available at: http://www.isiknowledge.com/