Participation of the state in the economic development of Russia's Arctic: privatization (historical aspect)

Автор: Zalkind Lyudmila Olegovna, Toropushina Ekaterina Evgenevna

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Development strategy

Статья в выпуске: 1 (31) т.7, 2014 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article considers the processes and results of privatization of enterprises taking place in the Arctic regions of the Russian Federation in the period of 1991-2010. The authors study the aspect concerning the redistribution of influence (financial, political, etc.) between companies and the state, and between different levels of power. A conclusion has been made that the 2000-2010 period faced the intensification of transition from the direct intervention model, when the government acts as a regulator and entrepreneur, to the principles of indirect management.

Privatization, arctic, state policy, distribution of property

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223560

IDR: 147223560 | УДК: 332.1 | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2014.1.31.5

Текст научной статьи Participation of the state in the economic development of Russia's Arctic: privatization (historical aspect)

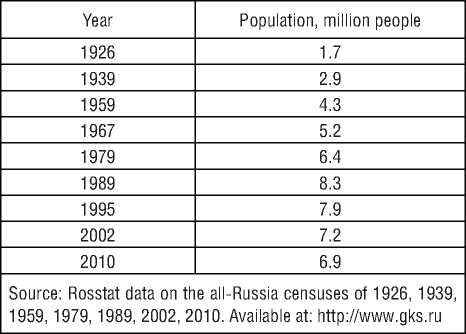

The necessity to protect its national interests was the driving force of Russia’s public policy (in the 19th as well as early 20th century) with regard to its Northern and Arctic territories. Certain countries strived to gain control over the Arctic archipelagoes, abundant in natural reserves, trying to take advantage of Russia’s lack of attention to its polar possessions. Such situation posed a threat to Russia. However, state policy was inconsistent and not focused due to the fact that the most important strategic interests of Russia were connected with the West and South, rather than the North, although the population of the Arctic regions1 was increasing throughout the 20th century (tab. 1) and it began to decline only at the end of the 20th century. At present, the population continues to decline.

From the mid-1930s, the state policy in the Arctic had undergone qualitative changes. The government began to regulate the processes of exploration and development of the territory. The desire to use natural resources for the development of national economy was the driving force of these processes. In 1933– 1935 the issues of studying, exploration and colonization of the Barents sea archipelagoes were handed over to the Main Department of the Northern Sea Route, the management of these processes became centralized.

A large-scale Soviet industrial development of the Arctic required considerable expenses. The geopolitical interests of the centralized state often prevailed over economic issues. High costs of Arctic’s development had been covered by cheap labor force for a long time. The rapid development of these territories in the 1930s was ensured by such organizations as

“Pechlag”, “Norillag”, “Dalstroy” and others that widely used the work of GULAG prisoners.

In the late Soviet period of development of the Arctic was guaranteed by government agencies – a system of powerful sectoral associations controlled from the center. High development costs were compensated by the extensive redistribution of oil and gas rent, which enabled (against the requirements of economic expediency) to subsidize prices, transport and energy tariffs, to provide the citizens with generous benefits and guarantees, and so on. The maintenance of control over the Arctic territories was ensured by the regime of strict forced centralization, directive government management.

Until 1991, almost all the enterprises in the country were state-owned, except for the property of co-operative enterprises, amounting to not more than 5%. In 1991, the federal government initiated the transfer of enterprises from state to private ownership; in this connection a number of normative acts [1, 3, 8, 12, 13] regulating this process were issued in 1991–1992.

The first stage of privatization consisted in the division of the unified state property by different levels [11, 15]; in this regard, military enterprises and facilities, ensuring the security of the country and other economic sectors

Table 1. The population of the Arctic regions of the Russian Federation

Table 2. Distribution of the enterprises in the Arctic regions by forms of ownership, %

Form of ownership Year 1996* 1999 2008 2010** State 30.6 7.1 5.8 4.6 Municipal 24.0 8.1 9.3 8.4 Private 6.8 68.4 74.5 79.1 Non-commercial 0.2 7.2 6.4 4.7 Mixed 38.4 9.3 4.0 3.1 * In 1996 the distribution is given according to the volume of main assets due to the absence of the data comparable with the subsequent periods. **Excluding the data on Taymyrsky and Dolgano-Nenetsky districts of Krasnoyarsk Krai. Source: calculated according to the Rosstat data. Available at:

(transport and energy infrastructure), large plants, universities, large suppliers of communal services, agricultural enterprises, etc. were assigned exclusively to the federal level. That is, almost all the enterprises in the Arctic became federal property (tab. 2) . Regional property was formed on leftovers, and its volume depended on the decisions of federal authorities.

The enterprises providing housing and utilities services, trade, healthcare, cultural facilities, etc. were assigned to the municipal level. Thus, the major property in the Arctic regions was distributed between the federal and municipal levels. As a result, municipalities received highly liquid property – shops and public amenities and less liquid property like municipal services, hospitals, requiring large investments.

Only minor enterprises were transferred to the regional ownership. For instance, in the Magadan Oblast only 45% of enterprises were transferred to the region’s ownership in 1993 out of the total number of enterprises that could potentially be transferred to the regional level. None of the companies that play a significant role in the region’s economy became regional property [31]. All 40 mining companies of the region that form its economy were transferred to the federal level. This separation of ownership made it possible to maintain the dependence of the regions from the center.

The second stage of privatization consisted in the process of “small” privatization and transformation of large and medium-sized enterprises into joint stock companies. “Small” privatization is the process of privatization of municipal enterprises: shops, cafes, hairdressing salons and barber’s shops, etc. This process started in 1992, and passed over its peak in 1992–1993 (after 1994 it was restrained legally [6]). But by 1996 already, the major part of these objects had been privatized. The most widely used method of “small” privatization was the sale of companies at special auctions2, part of the municipal property was transformed into joint-stock companies [21].

The process of “small” privatization in the Arctic regions began rather vigorously. For example, in 1992 in the Magadan Oblast 35 municipal objects (mostly shops and public amenities enterprises) were privatized, in 1993 – 250, in 1994 – 75, in 1995 – 69 objects (by 1996 most of them have become private).

The pace of this process was different in the Murmansk Oblast. Despite the fact that, according to the privatization program, it had been planned to privatize 524 such enterprises in 1992, only 126 of them were actually privatized, and in 1993 – 109 enterprises. Municipalities and the workers of enterprises tried to avoid privatization. Municipalities wanted to preserve their revenue base, which they were loosing in the process of privatization along with the enterprises. As for the workers of those enterprises, the entry into the free market demanded marketing efforts. If an enterprise retained its municipal status, it guaranteed a minimal wage and the possibility of being unprofitable. As a result, to the middle of 1997 only 406 municipal enterprises were privatized in the Murmansk Oblast [21].

Thus, the privatization of municipal enterprises was not full, but fast enough. A significant part (60–70%) of wholesale and retail trade enterprises, public amenities and public catering enterprises became private ones [35].

Small business emerged as a result of small privatization. The number of small enterprises in the Arctic exceeded 30 thousand in 1994. Then, by 1998, during the liquidation of unprofitable enterprises, the number of small enterprises decreased by one third. And only by 2006 the volume of small business recovered and exceeded the level of 1994. The number of small enterprises in 2010 amounted to about 65 thousand.

Enterprises belonging to the state property (including regional and federal property), were transformed into joint stock companies before

Table 3. The number of joint stock companies in the Arctic regions of the Russian Federation, created out of state and municipal enterprises

Year Number of joint stock companies, Increment total 1993 552 1995 1359 1997 1546 1999 1593 2001 1607 2003 1642 2005 1783 2007 1848 2009 1920 2011 1958 Source: calculated according to the Rosstat data. Available at: the privatization. In the Arctic regions about 1500 state enterprises were incorporated in 1993–1999, and more than 300 – in 2000– 2010.

The process of corporatization went on by leaps and bounds. For instance, in 1993–1994 111 enterprises of federal and regional ownership in the Magadan Oblast were transformed into joint-stock companies, which was not more than 15% of all the enterprises [31]. The most part of the enterprises went through the process of corporatization in 1996 (tab. 3) . In 1998–2001 there was a decline in the process of corporatization. But by the end of the 2000s, all the large and medium enterprises of the federal and regional ownership subject to privatization, became joint-stock companies.

All in all, 152 joint stock companies were formed in 1992–1996. In this period, all the large enterprises playing a crucial part in the region’s economy were reincorporated as joint-stock companies. Then, up to mid-2000s, the process stopped, and then went on by transforming state unitary enterprises into joint-stock companies3.

The third stage of privatization consisted in the placement of shares of the privatized enterprises. Part of the shares in 1992–1996 was transferred free of charge to the employees of these enterprises; the remaining part of the shares was sold by the State Property Fund at auctions or left as a fixed state package. During the period of corporatization the concept of “golden share” was introduced. A “golden share” is a share, which for a certain period of time4 provides the state body with the decisive vote at shareholders’ meeting. In 1995 the state retained control over 28% of the Arctic enterprises, which were privatized this year, in the form of controlling interest and/or the

“golden share” [35]. In general, the process of corporatization and transition from state to mixed, and then private form of property took 3–4 years.

Regional authorities could retain their influence not only in case of direct control. For example, in 1998 the owners of the enterprises Severonickel and Pechenganickel5 intended to close them due to an unfavourable economic situation in the world nickel market. Due to the active intervention of the regional government and under its pressure a new company was established, OJSC Kola Mining and Metallurgical Company, which is operating efficiently at present. The regional government used indirect leverages6 over the company’s owners.

The difficult situation, which the enterprises had to face after privatization, often served as the basis for state intervention. In 1996 the state regained 25% of the shares of JSC Kovdorsky GOK, one of the largest enterprises in the Murmansk Oblast (by order of the court, for the non-fulfillment of the investment terms of privatization) [22]. The enterprise was on the verge of bankruptcy. In early 1997 21% of Kovdorsky GOK shares were returned (in the pre-trial settlement) to the municipal ownership of Murmansk. I.e. the regional government controlled 46% of the shares, which ensured full control over the enterprise, because another significant package of about 30% was sprayed between the employees of GOK. The regional government managed to stabilize the company and to establish production distribution; as a result, by 1999 the plant has made profit of 30 million rubles a year. In 2001, a decision was made on the sale of the state and municipal stock of shares. The private company OJSC MCC EuroChem became the owner of OJSC Kovdorsky GOK.

At the same time, regional authorities tried to retain their influence over the enterprises located on their territory. The reason for this can be found in the fact that in most of the Arctic regions the company’s assets are “stationary”, i.e. closely attached to a particular space. And an important issue was who controls these enterprises: the “insider” business structures, closely cooperating with regional and municipal authorities, or “outsider” structures that are difficult to influence. Therefore, regional authorities actively interfered into the process during the initial division of state property and also during the subsequent periods of transformations, seeking either to establish their direct control over the main assets of the territory, or appoint their “insider” owners hereto. For example, in the 1990s, on behalf of the Komi Republic residents, a group of the region’s top managers gained control over the major large enterprises and subsoil areas rich in mineral resources [30]. The struggle of the “outsider” private capital for regional ownership ended in 2001 by the change of the regional power and complete transfer of major enterprises in private hands [29].

However, the cooperation between regional authorities and large enterprises is maintained through the “migration” of officials in the governing bodies of enterprises and vice versa. By placing officials as heads of the boards of directors, the government regained control over large enterprises, especially over energy giants.

However, one can find some examples of a significant decrease in the influence of the state, when regions are turned into quasi-corporations and they are subsidized by large companies [19, 28]: for example, JSC RAO Norilsk Nickel, which forms an almost entire budget of Taimyr

Autonomous Okrug and directs a significant amount of finances to its social sphere. Norilsk Nickel has an almost complete control over Taimyr AO. The merger of the corporation and the region has reached the maximum level, since the corporations’ representatives can belong to power structures and they are even appointed as region’s governors. As a result, large companies and the region become a single unit, they become responsible for economic and social policy and for the functioning of public services, regional infrastructure, etc.

The redistribution of influence is going on not only between companies and the state, but also between the levels of authorities. It often takes place by establishing formal environmental and social constraints for corporate structures. Regional authorities in Khanty-Mansi AO, after losing some of their powers in the sphere of subsoil use (due to the transfer of the main control functions to the federal level) in 2004 approved the new maximum permissible levels of water pollution for oil and gas companies [29]. This innovation was aimed at regaining partial control over large external owners in the okrug, since, despite the long-standing need for tougher environmental standards, the region has introduced them only when it lost actual rights of control over and direct influence on the companies.

Making strategic sectors (fuel and energy complex, transport, communication) the priority spheres of state control and regulation is becoming the main tool for the implementation of the state policy in the Arctic [33]. This occurs through the formation of large business-structures, which consolidate in their hands the right of control over the most valuable assets of the territory: for example, AK ALROSA is such super-organization in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia).

In the mid-2000s, federal authorities continued to pursue the policy of further privatization of enterprises. According to the law [4], by 2009, local authorities were bound to either privatize or transfer to the state ownership the property that did not ensure the performance of their functions. Only schools, kindergartens, polyclinics and hospitals could remain in the municipal ownership.

A similar decision concerning state property privatization was made in respect of enterprises, which do not provide the performance of public functions. Since 2005, the state has been reducing the number of unitary enterprises [10]. Most of them underwent the procedure of incorporation with the preservation of 100% of shares in state ownership. Then they were offered for privatization. Besides, it was proposed to privatize the packages of shares that belonged to the state and the size of which did not exceed 50% of the authorized capital; any shares of fuel and energy complex companies, civil aviation, etc., including the shares of the enterprises that were previously on the list of strategic enterprises not subject to privatization.

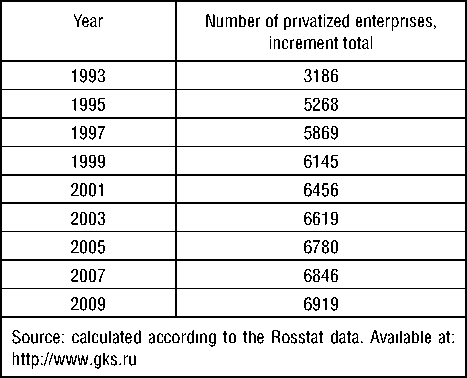

In the Arctic regions for the 1992–1999 period over 6000 enterprises were privatized (tab. 4) . For 2000–2009 almost 800 enterprises were privatized in the framework of the program for selling non-core state and municipal property. Despite such significant rate of privatization, about 50% of the enterprises,

Table 4. The number of privatized enterprises in the Arctic regions of the Russian Federation

out of their total number in 19907, have been privatized so far. Many enterprises remain in state ownership, although they have changed their organizational form, the others have been liquidated or reorganized into other forms.

By 2007, the federal government had retained direct control over more than 600 enterprises, registered or operating in the Arctic regions. Among them 34 enterprises of federal ownership with a 100% package of shares belonging to the state, 3 – with a package of shares over 50%, 9 – with a package of 25–50% and 8 – with a package less than 25% were subject to further privatization8. These were partly the enterprises, which had not found buyers previously9, or the enterprises of nuclear industry and military complex.

The enterprises that had not been privatized often remain in state ownership due to the lack of individual entrepreneurs willing to buy them. 80 enterprises were prepared for privatization and 29 privatized in 2007. The next year an attempt was made to privatize even more enterprises (about 120), but only 39 were privatized [26]. The reasons for these failures, in addition to low economic attractiveness of the asset of these enterprises, include their excessive price at the auction and sale in single lot.

In recent years, the share of joint stock companies fully owned by the state has increased in Russia as a whole. We can assume that the same tendency is typical for the Arctic regions. According to incomplete data, by 2010 the federal government has maintained control over the enterprises through equity participation in more than 200 enterprises located in the Arctic regions, and it has been the owner of about 400 unitary enterprises.

In addition, the list of strategic companies of the Russian Federation (i.e. not subject to privatization) contained 12 more enterprises, which were registered or operating in the Arctic. About 40 enterprises, previously included in the list, were excluded from it (which does not mean their privatization; most of them were transformed into joint stock companies with 100% state package or included in the state corporations).

In general, we can observe the increase of state control, but mainly in relation to key natural resources. Russia is distinguished by the fact that the state’s part of economic rent from oil and gas extraction and from the production of diamonds in Russia’s Arctic goes almost exclusively to the federal level. Priority state control and regulation are carried out with regard to such strategic sectors as fuel and energy complex, transport and communications.

One can also find some examples of a significant reduction in the state control, when corporations have such a considerable impact (financial, political, etc.) on the region’s development that the space is actually privatized together with the institutional infrastructure, and the territory becomes a quasi-corporation.

There is certain progress in the transition from the model of direct policy intervention, when the state acts as regulator and as entrepreneur, to the principles of indirect management. The influence is redistributed between the companies and the state, as well as between different levels of power. The establishment of formal environmental and social constraints for corporations is one of the instruments of such indirect influence.

Besides, it is necessary to consider the process of housing and utilities enterprises’ privatization, which was held in the framework of the housing reform launched in 1992. Earlier, all the housing and utilities enterprises in the Arctic regions were either in the municipal or departmental ownership. The main purpose of the housing reform was to reduce state funding of the housing sector in the conditions of the high budget deficit. The housing reform was also aimed at enhancing the quality of housing and the quality of communal services.

The following measures were proposed to achieve these goals [2, 9, 14]:

-

• privatization of residential premises (for details see [18]);

-

• demonopolization of the housing and communal services market through the liberalization of supply and demand in this market;

-

• changes in the policy of state subsidies: the reduction of state services in the housing and utilities sector, transition from the provision of subsidies to utility companies to the subsidization of persons with low incomes;

-

• increase of prices for housing and communal services for the purpose of increasing the attractiveness of the sector for private business.

Organizations involved in the management of houses, remained in the municipal ownership for a long time. On the one hand, it was due to the willingness of municipalities to retain control over the financial flows, which were comparable with the volumes of municipal budgets. On the other hand, it was conditioned by the fact that the residents themselves considered the municipal company to be more reliable than private management companies that could significantly raise the cost of houses’ maintenance.

The establishment in 2007 of the state corporation, the Fund for Support to the Reforming of Housing and Utilities Sector (hereinafter – the Fund) changed the situation with the participation of state and municipal authorities in the housing sphere [5]. In 2007 only one region, Karelia, out of the nine Arctic regions, for which statistical data are available, was ready to comply with the conditions of the Fund. On the whole, in all the Arctic regions private managing companies accounted for about 50% of the housing services market only in eight cities located in four regions. In 2008 seven out of nine regions complied with the requirements concerning the commercialization of the management services market. In 2010 the share of private managing companies exceeded 50% of the housing fund in five regions, in three regions it amounted to about 40% and only in Chukotka AO10 it was 20% [27].

Many private management companies emerged after the reorganization of municipal management companies into private ones, as a rule, through corporatization. The city authorities tried to maintain their influence in the new companies through their ownership of 25% of shares or more. In Murmansk, for example, in 2008, the municipal management company was transformed into three jointstock companies, in all of them the municipal government owned from 40 up to 50% of the shares through other municipal enterprises (which allowed it to bypass the requirements of the Fund). These three companies managed 94% of the city housing fund. However, the changes in the government (change of the mayor and the coming of new people to power), as well as the struggle inside the power structures resulted in the creation of new, fully private, management companies, which, using the administrative resource, gained most of the housing fund of the city. At the beginning of 2010 there were about 12 management companies [24].

With the help of the administrative resource attempts were made to intercept the financial flows directed from the federal budget for the capital repair of houses.

Associations of owners and the “outsider” managing companies at the regional level were forced to accept the choice of certain contractors for capital repairs, as it happened in the Murmansk Oblast in 2010 [23, 32]. In the early summer of 2010, financial resources were allocated from the Fund for capital repairs to the number of management companies. The regional authorities, who were the managers of these funds, claimed that the main condition for receiving the money was the competition among the contractors. The organization of the competition caused the 3–4 month delay in receiving the money. It means that the works could actually start in autumn or early winter. It is unacceptable in the Arctic conditions, since the cost of works increases greatly in the autumn and winter period. Furthermore, according to the terms of the competition, the contractors had to belong to one and the same self-regulatory organization of builders that included only large firms, for which the proposed works were of little interest. As a result, even though the organizations that had won the competition, fitted the necessary requirements, the contractors could not get to work immediately [16, 17], because the regional authorities detained the transfer of the necessary documents. Therefore, the authorities still tried to influence the processes in the housing sector, and maintain control over financial flows.

Another condition, upon which the Fund would grant budget subsidies, was that the housing fund had to be serviced by private utility companies. By 2010 their share was to be not less than 50% of the housing fund, by 2011 – at least 80%. The total share of the municipality and the region in these companies could not exceed 25%.

As a rule, most of the communal enterprises operated in the form of either municipal or regional unitary enterprises. The requirement of the Fund concerning privatization was fulfilled slowly. For instance, only two out of the five major water supply enterprises in the Murmansk Oblast have been made joint stock companies by 2010, with 100% state and municipal capital (JSC Apatityvodokanal and JSC Monchegorskvodokanal). Three water supply enterprises, one of which was the largest in the oblast, remained unitary enterprises (state regional unitary enterprise Murmanskvodokanal, municipal unitary enterprise Severomorskvodokanal, state regional unitary enterprise Kandalakshavodokanal).

Heat and power supplying companies, as a rule, are joint-stock companies. However, all of them are part of large companies, which include many re-allotted joint-stock companies. In turn, some of these large companies standing on the top of the pyramid have state presence, some do not. The heat supply enterprises owned by the regional government, usually go bankrupt. It happens mainly due to the fact that they accumulate sufficient debts to fuel suppliers caused by consumers’ nonpayments. In 2005 in the Murmansk Oblast five organizations providing heat supply to 70% of the region’s population were combined into one regional unitary enterprise (GOUTP Tekos). This company, which operated with losses in 2005–2009, has been continuing to balance on the brink of bankruptcy up to the present time.

The problem of heat supply remains very acute for the Arctic regions. All urban settlements have a centralized heat supply scheme. Worn-out heat systems, debts, accumulated by the population and enterprises lead to the fact that the settlements remain without heat for the winter period. The cost of fuel delivery in some remote settlements is so high that their residents have to pay 10–12 times more for the heating of 1 square meter than in the oblast center [20]. In this regard, municipalities are provided with subsidies from regional budgets (in special cases – from the federal budget) for the purchase of fuel (in the framework of the “northern delivery”) and repair of heating systems.

Heat supply to the Arctic regions, especially the outlying settlements, is effected through the so-called “northern delivery”11. In the 1990s, the financing of fuel and food deliveries was carried out according to the following scheme: the federal budget allocated target budget loans to the regions according to their applications. Then regional budgets had to return these funds to the federal budget, but, due to the lack of resources in the majority of regional budgets, the funds were not returned in most cases. In 1999 the mechanism of financial support to the “northern delivery” somewhat changed. The Fund of target-oriented subventions was established, and its resources were allocated to the regions for providing gratuitous financial assistance in the organization of the “northern delivery”. The right to issue interest-free budget loans from the federal budget was retained.

In 2005 the mechanism of providing support to the “northern delivery” changed: the regions themselves became responsible for the “northern delivery” in their territories [34]. Currently, the state support of the “northern delivery” consists in the preliminary allocation of a budget loan for the purchase of necessary food and fuel and their delivery with the subsequent loan repayment [36].

The tendency of reduction in the federal funding and state influence is typical for all the spheres of life-support in the Arctic. Priority state control and regulation are carried out only with regard to strategic sectors (fuel and energy complex, transport, communication). Consequently, the main prospects of the national policy on the development of the Arctic are focused on the development of the Arctic seas shelf resources, on the development of transport corridors and infrastructure, and the provision of military security of Russia’s Arctic.

Conclusion

The Soviet model of state policy in the Arctic is characterized by its excessively centralized character, policy management and maximum participation of the state in all spheres of life. The reforms of the Soviet political and economic system fundament-ally changed the attitude of the state to the Arctic regions. There was a transition from direct administrative control methods to indirect methods based on the legislative regulation, the use of financial tools and informal interaction.

State presence in the economy of the Arctic regions has decreased due to the transfer of the rights of ownership on a considerable part of companies to the private sector. But the state maintains the ownership of land and natural resources; it also owns the enterprises that are strategically important for the country. At the same time, municipal ownership has been essentially eliminated and the municipalities have very few actual tools of influence on the socio-economic situation.

The state property in the housing sector was almost completely turned into municipal and private property. A lot of companies that provide housing and communal services are becoming private, and this trend is increasing. State support, primarily the financial support of housing, utilities and infrastructure in the remote areas of the Arctic has been reduced.

Thus, we can point out that the state management and control has enhanced in recent years, but only with regard to key natural resources. As for other spheres, they are facing the transition from the model of direct policy intervention to indirect management.

Список литературы Participation of the state in the economic development of Russia's Arctic: privatization (historical aspect)

- O privatizatsii gosudarstvennykh i munitsipal’nykh predpriyatiy v Rossiyskoy Federatsii: Zakon RF ot 03.07.1991 №1531-1 (red. ot 17.03.1997) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- Ob osnovakh federal’noy zhilishchnoy politiki: Zakon RF ot 24.12.1992 №4218-1 (red. ot 22.08.2004) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O privatizatsii gosudarstvennogo i munitsipal’nogo imushchestva: Federal’nyy zakon ot 21.12.2001 №178 . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- Ob obshchikh printsipakh organizatsii mestnogo samoupravleniya v RF: Federal’nyy zakon ot 06.10.2003 №131 . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O Fonde sodeystviya reformirovaniyu zhilishchno-kommunal’nogo khozyaystva: Federal’nyy zakon ot 21.07.2007 №185 (red. ot 05.04.2013) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O Gosudarstvennoy programme privatizatsii gosudarstvennykh i munitsipal’nykh predpriyatiy v Rossiyskoy Federatsii: Ukaz Prezidenta RF ot 24.12.1993 №2284 (red. ot 28.09.2011) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O merakh po realizatsii promyshlennoy politiki pri privatizatsii gosudarstvennykh predpriyatiy: Ukaz Prezidenta RF ot 16.11.1992 №1392 . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- Osnovnye polozheniya Gosudarstvennoy programmy privatizatsii gosudarstvennykh i munitsipal’nykh predpriyatiy v Rossiyskoy Federatsii posle 1 iyulya 1994 g.: Ukaz Prezidenta RF ot 22.07.1994 №1535 . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O reforme zhilishchno-kommunal’nogo khozyaystva v Rossiyskoy Federatsii: Ukaz Prezidenta RF ot 28.04.1997 №425 (red. ot 27.05.1997) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- Ob utverzhdenii Perechnya strategicheskikh predpriyatiy i strategicheskikh aktsionernykh obshchestv: Ukaz Prezidenta RF ot 04.08.2004 №1009 (red. ot 01.10.2010) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O razgranichenii gosudarstvennoy sobstvennosti v Rossiyskoy Federatsii na federal’nuyu sobstvennost’, gosudarstvennuyu sobstvennost’ respublik v sostave RF, kraev, oblastey, avtonomnykh oblastey, avtonomnykh okrugov, gorodov Moskvy i Sankt-Peterburga i munitsipal’nuyu sobstvennost’: Postanovlenie VS RF ot 27.12.1991 №3020-1 (red. ot 24.12.1993) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- Ob utverzhdenii prognoznogo plana (programmy) privatizatsii federal’nogo imushchestva na 2007 g. i osnovnykh napravleniy privatizatsii federal’nogo imushchestva na 2007-2009 gg.: Rasporyazhenie Pravitel’stva RF ot 25.08.2006 №1184-r . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- Ob utverzhdenii Polozheniya ob opredelenii poob”ektnogo sostava federal’noy, gosudarstvennoy i munitsipal’noy sobstvennosti i poryadke oformleniya prav sobstvennosti: Rasporyazhenie Prezidenta RF ot 18.03.1992 №114-rp . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O Gosudarstvennoy tselevoy programme “Zhilishche”: Postanovlenie Pravitel’stva RF ot 20.06.1993 №595 (red. ot 26.07.2004) . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- O razgranichenii predmetov vedeniya i polnomochiy mezhdu federal’nymi organami gosudarstvennoy vlasti RF i organami vlasti kraev, oblastey, gorodov Moskvy i Sankt-Peterburga RF: Federativnyy dogovor ot 31.03.1992 . Available at: http://www.consultant.ru/.

- Gerchina O. S pravitel’stvom ne soglasny! . Dvazhdy Dva Newspaper, 2010, issue of July 30.

- Gerchina O. Zhdat’ net sil , Dvazhdy Dva Newspaper, 2010, issue of September 24.

- Zalkind L.O., Toropushina E.E. Zhilishchnaya politika v Rossii: Severnoe izmerenie . Apatity: KNTs RAN Publ., 2009. 230 p.

- Zelenko B.I. Finansovo-promyshlennye gruppy v rossiyskom politicheskom protsesse . Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya , 2004, no.5, pp. 108-113.

- Zolotoe teplo . Available at: http://www.turuhansk-region.ru/publ/5-1-0-52

- Zubareva T.A. Ot gosudarstvennoy sobstvennosti -k chastnoy i smeshannoy formam sobstvennosti (na primere raboty Fonda imushchestva Murmanskoy oblasti) . Sever i rynok . Apatity: KNTs RAN Publ., 2000, No.1, pp. 152-156.

- Kvitko E., Telen’ L. Ochen’ spetsial’nyy auktsion. Moskovskie novosti , 2001, issue of June 12.

- Kommunal’noe reyderstvo v assortimente . Vestnik zhilishchnogo samoupravleniya , 2009, no.2. Available at: http://tsg-rf.ru/book/export/html/253

- Nikitin A. Zhilishchno-kommunal’naya khvatka . Novyy Vest-Kur’er , 2009, issue of April 29.

- Otchet Federal’nogo agentstva po upravleniyu gosudarstvennym imushchestvom za 2003 g. . Available at: http://www.old.rosim.ru

- Otchet Federal’nogo agentstva po upravleniyu gosudarstvennym imushchestvom za 2008 g. . Available at: http://www.old.rosim.ru

- Otchety Gosudarstvennoy korporatsii -Fonda sodeystviya reformirovaniyu zhilishchno-kommunal’nogo khozyaystva za 2007, 2008, 2009 gg. . Available at: http://www.fondgkh.ru/result/index.html

- Pachina T. Pochivalova G. Eksterritorial’nost’ kapitala syr’evykh korporatsiy: regional’nyy aspekt . Problemy prognozirovaniya , 2005, no.5, pp. 85-95.

- Pilyasov, A. Regional’naya sobstvennost’ v Rossii: svoi i chuzhie . Otechestvennye zapiski , 2005, no.1, pp. 84-111.

- Respublika Komi: ot Spiridonova k Torlopovu i obratno . Komi News Portal. February 06, 2007. Available at: http://www.komi.in/archive/2007/02/06/003765.html

- Rossiyskiy Sever i federalizm: poisk novoy modeli . Ed. by A. Pilyasov. Magadan: SVKNII DVO RAN, 1997. 180 p.

- Severnyy shantazh. U chinovnikov Murmanska est’ proverennoe nou-khau . Vestnik zhilishchnogo samoupravleniya , 2009, no.2. Available at: http://tsg-rf.ru/book/export/html/253

- Selin V.S. Ekonomicheskiy krizis i ustoychivoe razvitie severnykh territoriy Sever i rynok . Apatity: Izd-vo KNTs RAN, 2011, no.1(27), pp. 20-25.

- Serova V.A. Analiz zakonodatel’nogo obespecheniya sistemy “severnogo zavoza” v rayony Kraynego Severa . Sever i rynok , 2007, no.17, pp. 40-48.

- Khod privatizatsionnogo protsessa v 1995 g. . Federal Portal protown.ru. Available at: http://www.protown.ru/information/hide/3068.html

- Shpak A.V., Serova V. A. Problemy i sovremennye tendentsii formirovaniya transportnoy infrastruktury na Severe . Sever i rynok: formirovanie ekonomicheskogo poryadka , 2011, no.1, pp. 165-170.

- Calculated using the Rosstat data. Available at: http://www.gks.ru

- Calculated using the data of the Federal agency for state property management. Available at: http://www.old.rosim.ru