Performative strategies in contemporary Chinese avant-garde poetry

Автор: Dreyzis Yulia A.

Журнал: Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: История, филология @historyphilology

Рубрика: Литература стран Восточной Азии

Статья в выпуске: 10 т.19, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The paper presents an attempt to explore the problem of mediality in Chinese poetry of the last thirty years. New Chinese poetry is particularly susceptible to the influence of the latest concepts of modern art and now more than ever needs a clear contextualization in relation to other forms of culture and avant-garde practice. This can be achieved through applying an analysis paradigm for performative word art developed by Dr. Tomáš Glanc in the context of Czech and Russian neo-avant-garde. It perceives experimental poetry as a form that fulfills a shift of the word thus making it labile. Examples of this phenomena can be found in Chinese poetry in the works of Ouyang Jianghe, Yang Xiaobin, Ouyang Yu, Xia Yu, Chen Li, Xu Bing, Wuqing and many more experimental artists. Their creative use of word shift principles shows how performative strategies are adapted in contemporary Chinese poetry keeping in mind the specific hanzi (character) medium that it is based upon. It seems both a continuation of a long-existing tradition and a radical exploration of the ‘iconic turn’ in the field of language.

Chen li, contemporary china, experimental poetry, internet poetry, language shift, ouyang jianghe, ouyang yu, prc poetry, taiwan poetry, text linguistics, web poetry, wuqing, xia yu, xu bing, yang lian, yang xiaobin

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147220390

IDR: 147220390 | УДК: 82-1, | DOI: 10.25205/1818-7919-2020-19-10-100-116

Текст научной статьи Performative strategies in contemporary Chinese avant-garde poetry

This paper is an attempt to explore the problem of mediality in Chinese poetry of the last thirty years. Poetic text as we know it, in our era of interdisciplinary connections, seems to be rapidly becoming obsolete. Avant-garde poetic forms, such as visual, sound, performative poetry, directly involve the experience of related art forms, creating a fundamentally new artistic production. At the same time, the poetic text itself, the one we are accustomed to perceiving, undergoes significant changes. The poem can converge directly with other formats and can implicitly borrow their technique and optical effects by emphasizing complex patterns of visual setup or applying some features of the musical form.

Chinese poetry is particularly susceptible to the influence of the latest concepts of contemporary art since the early 1990s. Now more than ever it needs a clear contextualization in relation to other forms of culture and avant-garde practice. One of the possible contextualizations is based on applying an analysis paradigm for performative word art as developed by Dr. Tomáš Glanc in the context of Czech and Russian neo-avant-garde 1.

At the centre of Glanc’s conception lies the idea that the main feature of the performative avant-garde poetry is the way it deals with the mediality 2 of the poetic word. This type of poetry is a practice that somehow involves the shift of the word – as a material unit and as a unit, which is taken for granted within the framework of the linear sequence of the text, thereby creating the phenomenon of the labile word. The word starts vibrating in its elementary presence as part of the textual sequence.

Starting from this thesis, Glanc offers a set of characteristics of the experimental verse related to its special properties that involve the shift of the word. The practice of performative poetry is closely linked with samizdat activities across the Eastern Bloc, in which individuals reproduced underground publications by hand and passed the documents from reader to reader. Vladimir Bukovsky summarized this grassroots practice as follows: “I write it myself, edit it myself, censor it myself, publish it myself, distribute it myself, and spend jail time for it myself” [Bukovsky, 1979. P. 141]. It created a mediality zone involving the physiological component that emphasized the connection between the word/letter and the paper or other types of carriers as a physically concrete plane and the one who produces the text as a guarantor of the labile connection.

This spatial dimension of the text is present in visual poetry at least since ancient times 3, but in contemporary poetry apart from being a continuation of the line that lasts for many centuries it comprises different attempts to save the word in the situation in which it appears in our hypertext, digital culture. The relationship between the text and the subject exist on the verge between literature and the material world/visual art. As Winfried Nöth puts it, the text manifests itself within the three dimensions reflecting the main dimensions of human orientation: the horizontal (right/left), the vertical (above/below), and the sagittal (front/back) [Nöth, 1996. P. 604]. In performative poetry, the horizontal dimension is actualized through the subversive practices that involve the linearity of the text, while the sagittal dimension becomes extremely important for its interaction with the me- dium involved (the opposition of the foreground and background somehow enters the semantics of the text).

This correlates with the idea of the ‘iconic turn’ that occurred in philosophy and social sciences in the 1990s. This idea was suggested by the Swiss art critic Gottfried Boehm and was associated with the recognition of the semantic autonomy of the image [Boehm and Mitchell, 2009]. For performative poetry, the iconic turn suggests that the text becomes actively involved in the process of its perception: the text appeals to the reader in a way that violates its usual existence. Not only do we perceive the text and consume it, but also the text actively looks at us revealing its plasticity. The intervention strategy in use is based on the principle that violates the status quo of the linear text. The spatial organization of the text per se in avant-garde poetry is an intervention in the field of text logic.

Today’s avant-garde poet in China has access to the Internet and many more small – and laxly controlled – publishing houses than the poet of the 1980s [Day, 2005. P. 11], which changes modes of operating with the text. To date the most comprehensive English-language study of developments after – and because of the influence of the early 1980s avant-garde – can be found in Maghiel van Crevel’s Language Shattered: Contemporary Chinese Poetry and Duoduo (1996). Modern Chinese Poetry: Theory and Practice since 1917 by Michelle Yeh (1991) is the best overview in English of the overall aesthetic development of twentieth century Chinese poetry to date, but it deals only briefly with the poetry of the 1980s. More information on contemporary poetry after the 1980s in Greater China 4 can be found in van Crevel’s Chinese Poetry in Times of Mind, Mayhem and Money (2008) and in the volume New Perspectives on Contemporary Chinese Poetry edited by Christopher Lupke, but none of them explores the phenomenon from the performative perspective. Other aspects of contemporary poetic practice in China that are closely connected with the performativity of the text have been explored in Modern Poetry in China: A Visual-Verbal Dynamic by Paul Manfredi (2014) and Verse Going Viral: China's New Media Scenes by Heather Inwood (2014).

This paper contributes to the current state of research in Chinese avant-garde poetry by applying the performative perspective as developed by Glanc that is deeply rooted in the linguistic approach, where the concept of the performative receives an expansive interpretation, levelling the difference between a communicative act and a social action. Its various implications are explored through the prism of Chinese avant-garde/unofficial poetry (and not necessarily only the works in the purely visual or concrete verse format) produced both in Greater China and beyond, in diasporas, which allows this poetry production to be included in the global context of the experimental art of the 20th and 21st centuries. This thesis will aim to illustrate this with several examples from the texts of poets who adhere to aesthetically different reference points (including the authors of both the popu-lar/ minjian 民间 and the intellectual/ zhishifenzi 知识分子 camps) 5. These pieces of word art are being considered and studied under the same category because contemporary ‘intellectual’ and minjian poets share a vision of the poetic as a ‘sublimation’ of the ordinary. In practice, they are increasingly aware that poetic language is itself a kind of deviation; it is a parade of abnormalities, even as it aspires to let the ordinary rule.

Just as his ancestor was convinced of the idealness of literature as a medium, the contemporary Chinese poet views poetic language as the ultimate form of language. Therein lies the paradox of contemporary Chinese verse: Chinese authors see themselves both as continuators of Chinese aesthetical and philosophical traditions as well as heirs of Western philosophy and Western modernism’s linguistic experimentation. They borrow traditional techniques such as parallelism, elliptical constructions, and nontrivial semantic links created through language phonographics to create connections with classical images and the tradition of 20th century Chinese ‘New Poetry’. Experiments of this sort expand the capabilities of language and construct a type of text that relies on unconventional usage supported by mechanisms for ensuring the semantic cohesion of the text; it explores language boundaries and opens Chinese poetry to the world.

Mediality: Subversion and Texturizing

Firstly, the idea of a subversive appellation to those moments of the text that codify it in language turns out to be extremely important for avant-garde poetry in China and beyond. The word seems to come out of its position under the influence of some kind of subversive mechanism. This technique plays a very important role in the work of one of the main pillars of ‘intellectual’ poetry – Ouyang Jianghe 欧阳江河 (b. 1956) 6. Already in his early poem Handgun ( Shouqiang 手枪 , 1988), the author breaks the words into their constituents, likening his experiment to the traditional fortune-telling practice of chaizifa 拆字法 : in the text of the poem, the banal word ‘gun’ recovers its internal form and turns into ‘hand + gun’7. In the collection Doubled Shadows (2012), translated by Austin Woerner, the poem appears three times: first in two separate free versions subtitled ‘after Ouyang Jianghe’, and once in an appendix that gives a more literal, annotated translation:

a handgun can be taken apart into two unrelated things a hand and a gun a gun lengthened becomes a Party

( 党 dang = any faction or political party)

a hand painted black becomes another Party and things themselves can be further disassembled

(东西 dongxi = thing, object; the characters 东 dong and 西 xi mean east and west, respectively) into pairs of opposing dimensions the world divides in infinite character-parsings

( 拆字法 chaizifa = the practice of parsing Chinese words into separate characters or characters into separate components, traditionally for the purposes of fortune-telling)

with one eye we look for love the other we ram down the barrel the bullets ogle our noses aim at enemies’ parlors politics tilt leftward a man shoots in the east in the west, a man falls the Mafia put on white gloves

( 黑手党 heishoudang, lit. “Black Hand party,” is the generic Chinese word for gangsters)

the Falangists switch to pistols

( 长枪党 changqiangdang, lit. “Long Gun Party,” is the Chinese name for the Falangists of Spain or Lebanon. 长枪 changqiang “long gun” originally meant spear, hence phalanx, hence Falangists.)

( 短枪 duanqiang, lit. “short gun,” means handgun or pistol)

eternal Venus stands in stone her hands rejecting humanity from her chest she pulls a pair of drawers inside, two bullets and a gun pull the trigger and it becomes a toy murder, hang fire

[Ouyang, 2012. P. 107]

Ouyang Jianghe brings this technique to the absolute in his long poem Phoenix ( Fenghuang 凤 凰 , 2012), where the tension between word and image creates a special combination of the wordimage or the image-word, a parallel for which can be found in the tradition with its calligraphic dimension of the poetic text [Ouyang, 2015]. It is noteworthy that Ouyang himself is not only a poet, but also a practicing calligrapher, and his poem was written as a tribute to the sculptor Xu Bing 徐 冰 (b. 1955) 8, who created a grandiose installation with the same name.

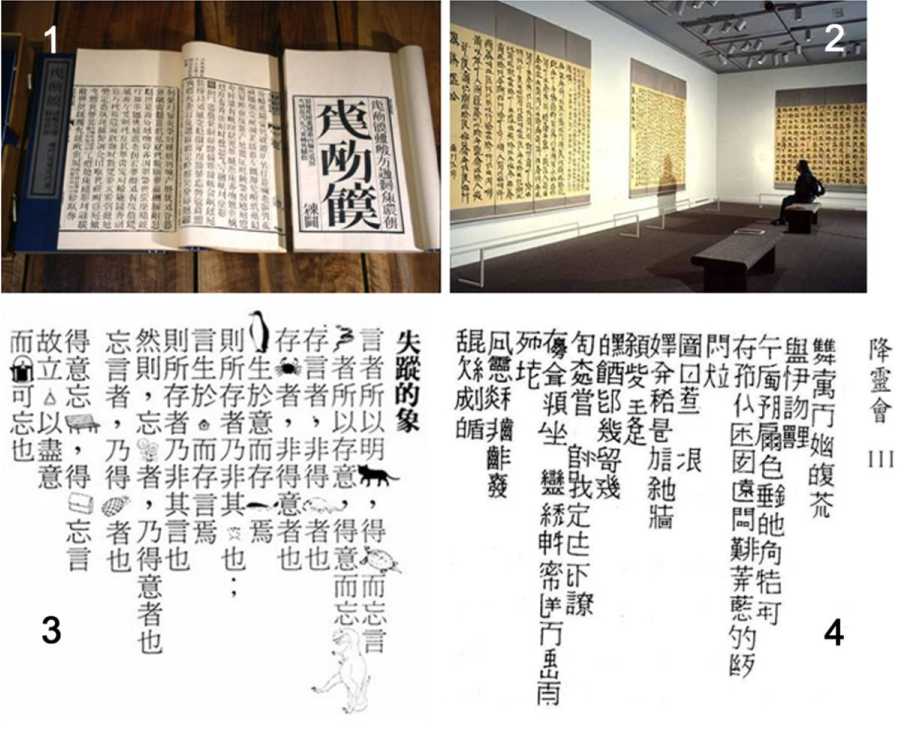

Xu Bing is interesting not only as the author of the stimulus to compose Ouyang’s Phoenix , but also as an experimental artist, who works with poetic texts, too. In his artworks, he exploits one of the strategies of performative poetry, turning the text into a background, a texture, and thereby creating a tension between the foreground and background, leading the text to ‘disappear’. For the Book from the Sky project ( Tian shu 天书 , 1987–1991) he created a huge mass of texts printed on paper and presented in the form of books and calligraphic scrolls; none of the 4000 characters involved exist in the Chinese script – they have all been created by Xu Bing himself 9 (Fig. 1, 1 ).

Another of his experiments related to recording of western poetic classics (for example, The Song of Wandering Aengus by W. B. Yeats) with signs imitating Chinese writing but representing a cunningly arranged stylization of the Latin alphabet. The experiment was called ‘Square Word Calligraphy’ 10 (Fig. 1, 2 ).

The material character of the text is projected into its semantics. It creates an effect of a semanti-cized form. The word does not have to be in a relationship of direct collision with visual units, so that it is clear that the sign system, which we call language, is under some kind of attack (under the influence of intervention), but the method of turning the text into a wallpaper, a texture, a façade generates a dissolution of the text. It becomes perceived through the body – its relationship with space, with singularity is now differently related to the human body (with a greater feeling of the form).

Fig. 1. Performative Strategies in Contemporary Chinese Avant-garde Poetry:

1 – Xu Bing, «Book from the Sky», 1987–1991. 100 boxed sets of 4-volume woodblock printed books. Image courtesy of Xu Bing Studio; 2 – Installation view of the exhibition ‘Word Play: Contemporary Art by Xu Bing’ at Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington D.C., 2001. Image courtesy of Xu Bing Studio; 3 – Hsia Yü, «Lost Image». Image courtesy of Hsia Yü; 4 – Hsia Yü, «Spiritism Session III». Image courtesy of Hsia Yü

Рис. 1. Перформативные стратегии в современной китайской авангардной поэзии:

1 – Сюй Бин, «Небесная книга», 1987–1991. 100 коробочных наборов 4-томных печатных книг. Изображение предоставлено Xu Bing Studio; 2 – Инсталляционный вид выставки «Игра слов: современное искусство Сюй Бина» в галерее Артура М. Саклера, Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, 2001. Изображение предоставлено Xu Bing Studio; 3 – Ся Юй, стихотворение «Утерянный символ». Изображение предоставлено Ся Юй; 4 – Ся Юй, стихотворение «Спиритический сеанс III». Изображение предоставлено Ся Юй

Intervention: Nontransparency and Spaciality

The works of Xu Bing can be considered the ultimate case of the implementation of intervention strategy when the very spatial organization of the text becomes an intervention in the field of its logic. This affects such an important criterion as the text’s readability – in normal, neutral perception this moment is neutralized, and we perceive the text as transparent. A counter example is the experimental text of the Taiwanese poet Hsia Yü 夏宇 (b. 1956) 11: her first collection Memoran- dum (Beiwanglu 備忘錄, 1984) was created, bypassing the commercial channels of publication, in the form of a poetic book of atypical form and size written in half-childish handwriting with illustrations resembling frames from cartoons. A typical example is the poem Lost Image (Shizong de xiang 失蹤的象), where all occurrences of the word ‘image’ are replaced by illustrations [Xia, 2001. P. 54–55] (Fig. 1, 3).

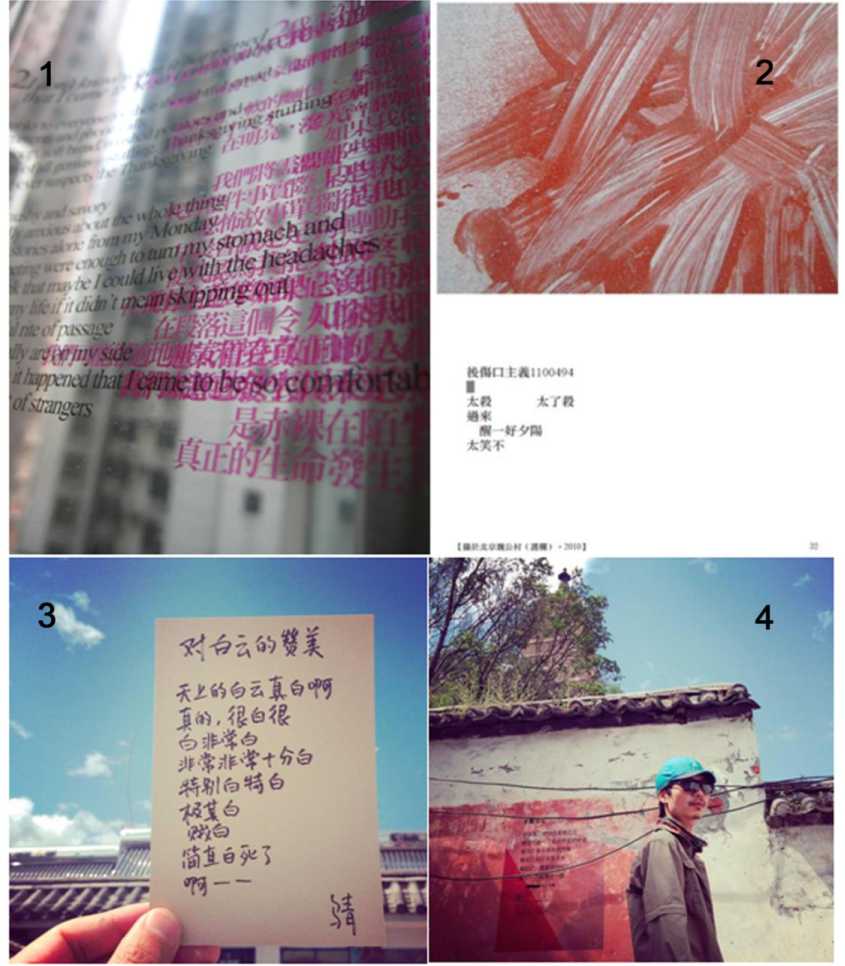

Fig. 2. Performative Strategies in Contemporary Chinese Avant-garde Poetry:

1 – Hsia Yü, Pink Noise cover; 2 – Yang Xiaobin, page 32 from Trace and Palimpsest . Image courtesy Yang Xiaobin; 3 – Wuqing, «Praise for the White Clouds». Image courtesy Wuqing; 4 – PoemHere project. Image courtesy of Wuqing

Рис. 2. Перформативные стратегии в современной китайской авангардной поэзии:

1 – Ся Юй, обложка книги «Розовый шум»; 2 – Ян Сяобинь, стр. 32 из книги «След и палимпсест». Изображение предоставлено Ян Сяобинем; 3 – Уцин, стихотворение «Хвала белым облакам». Изображение предоставлено Уцином; 4 – Проект «Стихотворение-здесь». Изображение предоставлено Уцином

This determined the model of all her subsequent books – Ventriloquism ( Fuyushu 腹語術 , 1990), Rub/ Indescribable ( Moca ‧ Wu yi mingzhuang 摩擦 ‧ 無以名狀 , 1995), Salsa (1999) and Pink Noise ( Fenhongse zaoyin 粉紅色噪音 , 2007).

Experiments with language as presented in Memorandum begin to play an increasingly important role in the poetry of Xia Yü. She creates pseudo-characters in the spirit of the avant-garde antiwriting in the poem Spiritism Session III ( Jiangling hui 降靈會 III, 1990) [Xia 2001. P. 45], while the book Rub/ Indescribable consists entirely of collages with fragments cut from the poems of the collection Ventriloquism (Fig. 1, 4 ).

Pink Noise contains thirty-three poems on a transparent film; each poem explores the topic of transparency of meaning and is presented in English (in one case in French) and in Chinese translation, and the Chinese text is coloured in bright pink (Fig. 2, 1 ).

Using transparent sheets of paper makes you think about the corporeality of the text and sets up non-standard relations with its material carrier. This is the moment neutralized in the usually printed text, however, within the framework of the experiment, its ‘thingism’ turns out to be incorporated into the semantics (the idea of text as a thing).

English poems of Pink Noise are text collages, while their Chinese translations were performed using the machine translation software Sherlock, as a result, they abound with translation errors and strangely worded Chinese phrases. Due to the use of an extreme degree of estrangement, the line between ‘original’ and ‘translation’, between ‘the language of the original’ and ‘target language’, is blurred, expanding in the process the signifying horizon of Chinese.

Similar experiments characterize the work of the Australian-Chinese poet Ouyang Yu 欧阳昱 (b. 1955) 12, who often uses a mixture of two languages within the space of one poem, down to their confusion within one language unit (as in the poem Di 皮 lation , 2010). His latest poetry collection boldly entitled Self Translation (2012) ends with three poems, organized quite nontrivially in terms of the visual, which combine two languages – Chinese and English. In 雙 /Double , he consistently translates each line of the poem – playing with the idea of alternation, including alternating black and white space on the page. This actualizes an important moment of the practice of performative poetry, i.e. the spatial dimension of the text, emphasizing lability – linear, material and physiological:

雙 /Double

Beautiful morning 美麗的清晨

A bird walks up to me 一頭鳥朝我走來

Like a chook

像只雞

Black across the breast

胸脯全黑

Right up to the hip 一直黑到屁股

I thought he might attack me 我以為牠會向我發起攻擊

With his heel-like beak 用牠像高跟的鳥啄 But he walks away 但牠走開了

And shits 拉了一泡屎 Before he takes flight 然後飛走

Leaving a pool of snow white 留下一灘雪白的東西 [Ouyang, 2012. P. 235]

The last poem of Ouyang Yu’s collection, Two Roads , returns the reader to the bilingual format of presentation, but now both pages of the turn include Chinese and English, which alternate not only line by line, but also within a single line. Two paired pieces present a reflection on the theme of The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost, they are designed to provoke a monolingual reader to take both roads (poems), reading Chinese or English words, jumping from the left to the right page and back. The last stanza in both cases is written in two languages, but the word ‘taken’ is removed from the English text and replaced with a Chinese translation and appears in the Chinese text on the left. The poem ends with an extra line in English in the left, mostly Chinese, stanza: ‘There's nothing you can’t do that you do’. On the opposite page, the stanza ends with the phrase ‘You have no choice, you have many choices’. To the left, it corresponds to an empty space – the potency of the translation that has not yet been realized.

兩條路

我的面前沒有那座林子 外面,黑夜越來越深 早已錯過了約會的時間 秋天,也許不久就回到來

The roads may have diverged in the woods

You can, though, travel in both

If only physically on one

While metaphysically on the other

一個人活久了就不是一個人

時光逐漸在肉中堆積

回頭路是沒有的

往前走的路也有盡頭

Two roads are two feet

That go way and come back

Who is there to say that future is not

The past and the time does not always stay?

Two Roads

The wood is not in front of me

Outside, the night deepens

I have long missed the hour of appointment

The autumn, it may soon arrive

路也許在林中分叉

但您能同時走兩條

一條用腳

一條用腦

One is no one when he lives too long

Time accumulates in the flesh

There’s no road back

Although the road forward does come to an end

兩條路就是兩隻腳 去去也就回了 誰能說將來不是 過去,時光永遠就不永駐 ?

沒有 taken 的路其實已經 taken

已經 taken 過的,不一定是必經之路

你別無選擇,你選擇很多

There's nothing you can’t do that you do

[Ouyang, 2012. P. 238–239]

The road not 走 has actually been 走了

The one走了的, not necessarily the one one wants to take

You have no choice, you have many choices

Contemporary Chinese poetry demonstrates a tendency towards converging word and image. Many authors use this convergence of visual and verbal as a means of renewing their poetics. It reflects not only an orientation towards a creative dialogue with the art of previous periods, but also the emergence of new expressive means that implicate language experiments (including words as asemantic images).

Examples of this approach include formal experiments of poet-cum-artist Yan Li 严力 (b. 1954) 13, calligraphic explorations of Ouyang Jianghe, and works of several poetry groups and circles, among others – the ‘Marvelous Enlightenment’ calligraphy school ( miao wu 妙悟 ) 14. This use of hybrid formats for information presentation captures new ways of visual-verbal interaction in rethinking of the literati tradition. At the same time, it constitutes a part of our need for surviving in a global text field, where misunderstanding of the text language in constant crossing of linguistic borders is increasingly becoming an important part of our practice.

In Chinese visual poetry, the most vivid examples of working with textual space are presented in the works of the Taiwanese poet Chen Li 陳黎 (b. 1954) 15 and, in particular, his famous War Symphony ( Zhanzheng jiaoxiangqu 战争交响曲 , 1995). In the works of Chen Li, the language itself becomes the aim and the object of the poem, representing itself.

兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵

兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵 兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵兵

兵兵兵兵兵兵兵乒兵兵兵兵兵兵兵乓兵兵兵兵兵兵兵乒 兵兵兵乓兵兵乒兵兵兵乒乒兵兵乒乓兵兵乒乓兵兵乓乓 乒乒兵兵兵兵乓乓乓乓兵兵乒乒乓乓乒乓兵乓兵兵乓乓 兵乒兵乒乒乒乓乓兵兵乒乒乓乓乓乓乒乒乓乓乒兵乓乓 乒兵乓乓乒兵乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓 乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓 乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓乒乒乓乓 乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓乒乓 乒乓乒乓乒乒乓乓乒乓乒乓乒乒乓乓乒乓乒乓乒乒乓乓 乒乒乒乒乒乒乒乒乓乓乓乓乓乓乓乓乒 乒乒乒 乓 乓乓 乒乓乒乒 乒 乓 乒乒 乒乒 乓乓

乒乒 乓乒 乒 乓 乒 乓 乒乒乒 乓 乒

乒乒 乓 乓乓 乒 乒 乓 乒 乓乒

乒 乓乓 乓乒 乓

乒 乓 乒 乓乓

乒乓

丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘 丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘丘

[Language for a New Century, 2008. P. 376]

In accordance with the typical structure of a musical symphony, the work breaks down into three fragments of the same size. The first consists of 384 characters 兵 bing (‘soldier’), arranged in the form of 16 lines with 24 characters each. They constitute a perfectly organized rectangle that evokes the image of a military parade. The second fragment introduces a certain irregularity: with the appearance of the characters 乒 ping and pang 乓 the whole structure crumbles, spaces appear, as they move downwards, they become larger. Ping and pang, differing from bing only by the absence of one of the bottom lines, write down onomatopoetic words hinting at the clapping of shots. At the same time, they look like images of soldiers with lost limbs. The last fragment restores the former orderliness: all the bing characters are replaced with 丘 qiu (‘hill’) – the soldiers end up in the grave 16.

This poem is remarkable for its ingenious use of graphics, but also the phonetics of Chinese language in their connection with each other. All three syllables bing , ping and pang are closed syllables and begin with stop consonants, while qiu begins with an affricate. This syllable is an open one, with an extended time of pronouncing. The presentation of the poem conducted by Chen Li himself additionally emphasizes the duration and aspiration of qiu , imitating the whistling of the wind. Thus, the last fragment of the Military Symphony not only visually represents a number of graves, but also complements this picture with the wind blowing over them. Qiu also has a homonym meaning ‘autumn’ – a concept traditionally associated in Chinese culture with the idea of the frailty of all existence and fanned by an atmosphere of sadness.

Chen Li's poem is not only a piece of evidence of how concrete poetry concentrates entirely on the language itself, it also illustrates the common concern of the contemporary Chinese poet with the problem of poetic language, his immersion in the discourse about poetic function understood in the spirit of Roman Jacobson [Jacobson, 1997]. Language is no longer a means of describing or transmitting facts, thoughts, and emotions; it becomes the goal and object of a poem, representing itself. Contemporary Chinese experimental poetry uses visual and acoustic aspects of speech as an object of poeticization; the signs of language are isolated from their conventional usage to lead the reader and listener to other semiotic dimensions.

Operating with characters, which are external to the language, also constitutes one of the strategies of performative verse, which explores the possibilities of double or even triple coding. The meaning of nonsingular coding is that other types of coding (visual, physical, spatial) are superimposed on language coding. This can be seen, for example, in the works of Yang Xiaobin 杨小滨 (b. 1963) 17 from the series Trace and Palimpsest ( Zongji yu tumo 蹤跡與塗抹 , 2005-2012), that combine the visual and the textual (Fig. 2, 2 ).

We also see it in Wuqing 乌青 (b. 1978) 18 in his project PoemHere ( Zheli you shi 这里有诗 , http://poemhere.org/ ), where the poetic text of a Web author ‘devirtualizes’ and begins to interact with the real space (Fig. 2, 3 , 4 ).

Self-Actualization: The Esoteric Dimension

For performative poetry, not only the spatial but also the ‘esoteric’ dimension of the text is quite significant, i.e. the phenomenon of self-actualization of the text – at the level of a semanticized form. It is observed in many poets, for example, in Yang Lian 杨炼 (b. 1955) 19. His long cycle Concen- tric Circles (Tongxinyuan 同心圆, 1994–1997) includes the poem Who (Shei 谁), where the words are devoid of any meaning, but the metric pattern of the work exactly corresponds to the traditional metric scheme of the cipai 词牌 Waves Washing Sands (Lang tao sha 浪淘沙):

烟口夜鱼前 风早他山 劳文秋手越冬圆 莫海噫之刀又梦 衣鬼高甘

宰宇暗丘年 随苦清湾 多眉不石小空兰 却色苦来黑见里 字水虫千

The word-for-word translation of the above-mentioned fragment looks like this:

smoke mouth in front night found mountains he morning grand labour text hand autumn round ocean knife dream never sand clothes ghost sweet tall sound all slaughter year dark mound bitter after blue-green band not stone brow stand small ground beauty come bitter black brand word water bug million resound

The English translation by Brian Holton presents an attempt to invoke the sound of the Chinese by substituting English words as close as possible to the sound of the Chinese. As Holton notes, Yang Lian suggested producing a text, which made no sense, yet had a structure, which was clearly visible in English20. After much experiment, he found the Welsh bardic metre Cyhydedd Hir, which is composed of an octave stanza of two quatrains with a strict rhyme-scheme. The title had to change from the original Who , which is the sense of the Chinese, to something closer to shui , the sound of the original:

SWAY yank so yeah you chin fen sought bam show shin choose ewe add fling sin moat high ease door fin eik wall gun gog sigh you anti dan squeak couching ban doe hay bushy shan coolie herring fan fizz way chaw cog [Yang, 2006. P. 78]

The effect to which the poet aspires is similar to the impression of an abstract painting, with the word as its material. In the poem Lie ( Huang 谎 ) of the same cycle, there is an entire line composed of more than twenty determinatives – graphic elements that do possess their own names but lack any phonetic correspondence and meaning, except for their function of thematic classifiers:

谎

美无家

美无 家无 之

色 无家可 归去来 辞

黄 红 蓝 白 黑 之受想行识

个条匹口头只双本页件台座辆棵片类次阵群

丿讠刂亻阝廴扌彳饣忄丬氵宀辶纟犭彡卄夂灬衤疒

说打喝演笑听看吃摸射飞重合传世垂钓催眠

死着 勤奋澄清着一杯啤酒的泡沫

石头借走 戴面具的经验

家 无 之 美

是真的 21

Holton’s ingenious translation that substitutes determinatives for English suffixes and prefixes reads like this:

LIES beauty sans home beauty sans home sans its colour sans home may Homeward Ho! say yellow red blue white black their rūpa vedanā samjña samskāra vijñāra score pound foot shoal pint flock sheet leaf brace volume gaggle fathom dram super al con ician mono ante ism per inity alysis cata intra ana ness pro ation ery say hit drink play smile eat touch shoot fly co-in-cide pisc-itate hypno-tise dying attending to clarifying the foam on a glass of beer stone borrows masked experience home sans its beauty is true

[Yang, 2006. P. 80]

Conclusion

The use of language shift principles shows how performative strategies adapt in the framework of contemporary Chinese poetry, linking radically new with deeply traditional – as it happens, for example, in the case of operating with the calligraphic dimension of the text. The concentrated nature of Chinese script provides opportunities to work with what Charles Olson called the ‘composition by field’ – movement across the entire surface of the page 22. In poetry, with Chinese characters as its medium, the possibility of close interaction and even the joint reading of words that are adjacent vertically existed even at the stage of classical verse, before the advent of the avant-garde. Graphic design is complemented by the alignment of the nominative series, the arrangement of words next to each other in an associative rather than a syntactic connection.

Contemporary Chinese poetry demonstrates a tendency towards converging word and image. Many authors use this convergence of visual and verbal as a means of renewing their poetics. It reflects an orientation towards a creative dialogue with the art of the past, but also an emergence of new expressive means that implicate language experiment. This use of hybrid formats for information presentation captures new ways of visual-verbal interaction in rethinking of the literati tradition. At the same time, it constitutes a part of our need for surviving in a global text field, where misunderstanding of the text language in constant crossing of linguistic borders is increasingly becoming an important part of our practice.

What we see here are the hidden esoteric dimensions of the text – not esoteric in the sense of spiritual practices, but in the sense of its self-realization. We are accustomed to perceive the text in avant-garde poetry as a kind of complication when compared to the ‘usual’ text of the quotidian, but it is also possible to (re)construct it as an eidetic reduction, as a kind of semantic cleansing. This presence of absence creates a vibrating sign, an image that is a way of speaking, albeit not in words, but in images (here again colliding with Boehm’s idea of the ‘iconic turn’). In Chinese, it is brought to life by exploring the mediality potential of the character.

Working with signs that are alien in relation to language raises the question of the transferability of sign, which has two vectors: an optimistic one (universality of semiotic systems) and a pessimistic one (each part of the sign is untranslatable in its singularity). Thus, the language comes out of the margins of its expressive means trying to express some types of meaning. This creates a hierarchy of text zones, a writing architecture presenting the text as a palimpsest (the title of Yang Xiaobin’s visual series Trace and Palimpsest is rather symptomatic in this respect).

Provocations / subversions of text reception and production are implemented through several techniques: texturizing, spacialization, opacity (nontransparency), and sign creation. The internal structure of the image, its connection with the material carrier and the potential of the image as a resource of knowledge – all is reflected both in the performative strategies of avant-garde art and in their ‘localization’ in the mainstream of the Chinese tradition, based on the special properties of its written signs. Both authors from Greater China and emigrants who have long been immersed in Western culture, people with different backgrounds, interests, political views, and the ability to orient in the Western aesthetic universe, form an artistic community that makes it possible to identify the features universal for the experimental word art as practiced by avant-garde poets writing in Chinese. The main universal is the actualization of the basic properties of Chinese character and the performative methods, which have been functioning since ancient times in the realm of Chinese culture.

Материал поступил в редколлегию Received 25.08.2020

Список литературы Performative strategies in contemporary Chinese avant-garde poetry

- Boehm G., Mitchell W. J. T. Pictorial versus Iconic Turn: Two Letters. Culture, Theory and Critique, 2009, vol. 50, p. 103-121.

- Bukovsky V. To Build a Castle: My Life as a Dissenter. New York, 1979, 438 p.

- Chernyavskaya V. E. Mediality: analyzing a new paradigm in Linguistics. Media Linguistics, 2015, no. 1 (6), p. 7-14. (in Russ.)

- Day M. China's Second World of Poetry: The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992. Leiden, 2005, 570 p.

- Grauz T. WORD. LETTER. IMAGE. On the Visual in Poetry. In: Parallel Processes in the Language of Modern and Contemporary Russian and Chinese Poetry. Ed. Y. Dreyzis. Moscow, 2019, p. 38-105.