Preconditions for the transformation of population's attitudes from political discontent to protest behaviour (as exemplified in the materials of ISEDT RAS, Vologda)

Автор: Afanasyev Dmitriy Vladimirovich, Guzhavina Tatyana Anatolyevna

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 6 (30) т.6, 2013 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article considers the issue concerning the transformation of political discontent to protest behaviour, which is insufficiently examined in the domestic scientific literature; the processes and factors facilitating this process are analyzed. The authors apply the empirical data of the monitoring of the public opinion of the Vologda Oblast residents, conducted by the Institute of Socio-Economic Development of Territories of the Russian Academy of Sciences. A new integrated model of protest is presented.

Political discontent, trust, protest potential, protest repertoire, protest participation model

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223526

IDR: 147223526 | УДК: 323.2

Текст научной статьи Preconditions for the transformation of population's attitudes from political discontent to protest behaviour (as exemplified in the materials of ISEDT RAS, Vologda)

The study of protest behaviour is an established and well-developed field of political sociology. However, a number of theoretical aspects have not been universally acknowledged yet. Our understanding of why people participate in protests is still far from complete.

Why does this very discontent result in mobilization, and not other? Or why does the same problem in one region of the country lead to mobilization, while other regions are still quiet? These questions are related to an acute issue, which is poorly presented in literature: the processes, by means of which a social urge to protest involves factors that turn the willingness of an individual to participate in a protest into the actual participation. The presented article, based on empirical data obtained in the course of ISEDT RAS (Vologda) long-term monitoring studies in the Vologda Oblast, is the authors’ attempt to illustrate the existing problems and to propose a combination of several theoretical concepts for their solution.

Classic definitions of a political protest describe it as a form or way of the individual’s political participation. On the societal level, when referring to a political protest, we point out the collective action that tries to modify a separate political decision, state policy or general relationship between the citizens and the state (political regime). Thus, we proceed from the interpretation of a political protest as a combination of political practices, carried out individually or collectively in institutionalized or non-institutionalized forms of expressing disagreement in relation to the functioning political subjects and systems. When studying the participation of citizens in political protest we try to answer the question “What are the origins and purpose of the protest?”, and consider the following major problems. Why do people protest? Is the purpose to transform the system, to change the rules of the political game or to change a particular political course? What are the forms of protest behaviour manifestation?

A. Hirschman’s concept is traditionally accepted as the general framework for analyzing the protest. It describes three possible ways of the behavioural reaction of the individual to a situation, in which he finds himself, – loyalty, if the individual is mostly or completely satisfied with the situation, and “voice” (protest) or “exit” (for example, emigration), if the situation is intolerable [7]. French sociologist Guy Bajoit added the fourth type of possible behavioural reactions –apathy, when the individual, dissatisfied with the current situation, takes no action to change the current situation, or to proceed to a different situation [9].

And while the protest (“voice”) refers to the real behaviour or active formulation and expression of dissent and criticism, the discontent is broader, since it comprises the individual’s attitude related to the level of his (dis)satisfaction within the existing political system. In this sense, the typology of protest forms, proposed by G.I. Weinstein as far back as 1990 [2, p. 25], a protest action (that is or has been implemented as action) and protest mood (something that is probably implemented as action), summarizing the heterogeneous phenomena (attitude and behaviour) under one concept of protest, complicates the understanding of the transformation process of the attitude into behaviour.

Obviously, such automatic correlation of the two concepts is not accidental, as it leads to postulating that the attitude of discontent leads to the actual expression of disagreement and therefore to protest. However, large empirical material relating to the description of the discontent level does not allow making such statement without significant reservations that call such firm and linear coupling in question.

Discontent, willingness to protest and real protest

The social sentiment index (SSI)1 is a popular tool for the integral evaluation of the social well-being of Russian citizens. This composite indicator is constructed as a single vector of interrelated political, economic, social assessments and opinions of people. The SSI can be interpreted as an integral indicator of the level of the population satisfaction/ dissatisfaction with various aspects of economic and socio-political reality, which in certain manner affects the real political and economic behaviour of the population.

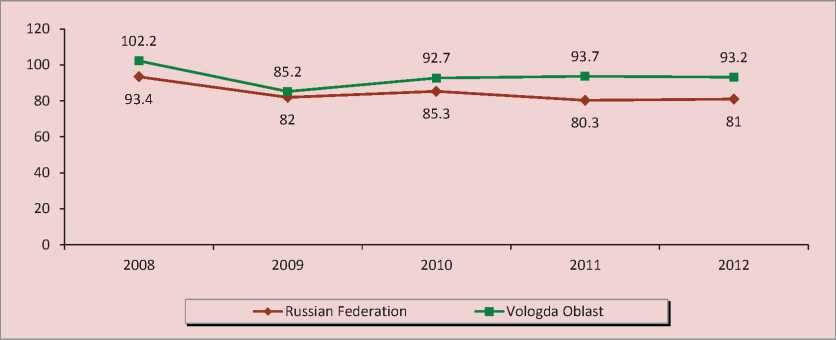

When comparing the available VCIOM data, as well as the results of the regional monitoring, held by ISEDT RAS under comparable methods, we obtain similar trends. The available data show significant SSI decline during the 2008–2013 period ( fig. 1 ).

The effects of the crisis, which has affected practically all Russian citizens, are evident. The Vologda Oblast suffered from the crisis more than many other regions and Russia as a whole. This is related to the fact that the the crucial part of tax revenues was provided to the region’s budget by the enterprises of the metallurgical industry that experienced a significant setback in production and has not yet returned to the pre-crisis level [4].

At the same time, the obvious deterioration of social feeling, expressed discontent does not automatically result in the growth of the population protest potential –willingness to participate in political actions.

The protests of the late 1990s were more radical and more focused on violent forms. For the last years the tendency to such actions as manning the barricades, participating in strikes and other similar actions decreased 3–5 times ( tab. 1 ).

Figure 1. Dynamics of the of social sentiment index in the Russian Federation and in the Vologda Oblast*, points

* VCIOM data; Vologdadata – ISEDT RAS under VCIOM methodology.

Table 1. Dynamics of the protest potential*, as a percentage of the number of respondents

|

Answer |

1998–1999 |

2007 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013, June |

|

Protest potential |

37.3 |

20.6 |

19.9 |

20.2 |

16.5 |

|

Go on a rally, demonstration |

9.4 |

9.6 |

10.9 |

10.3 |

9.3 |

|

Will participate in strikes, protest movements |

12.7 |

5.7 |

4.7 |

5.7 |

3.9 |

|

Take arms, man the barricades, if needed |

15.3 |

5.3 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

3.3 |

|

* The authors of the article “Main tendencies of protest moods in the Vologda Oblast” K.A. Gulin and I.N. Dementieva determine protest potential (protest group) as the share of respondents answering the question “What are you willing to do, in order to protect your interests?” as follows: ”I will go on a rally, demonstration”; “I will participate in strikes, protest movements”; “Take arms, man the barricades, if needed”, i.e. “the protest group” comprises people with various certain emotional moods, not necessarily identical to the active social behaviour, but admitting the possibility of their participation in protests in such way. See: Sociological surveys. 2008. No.11. November. P. 64-71. Source: ISEDT RAS monitoring data. |

|||||

The oblast residents clearly demonstrate the propensity for non-violent forms of expressing their disagreement with the policy of the authorities. In general, the protest potential in 2013 in the region is more than twice lower, as compared to the 1998–1999 period.

It is reasonable to highlight the gap between the marked increase of discontent, expressed in the SSI decline after the crisis, and the practical absence of the protest potential dynamics in the pre- and post-crisis period. The dynamics of the actual protests of the oblast population does not correlated neither with the dynamics of discontent, nor with the dynamics of protest moods. Rather, it points to loyal and apathetic political behaviour. This confronts us with the obvious research problem: how are political discontent, verbally claimed willingness to participate in protest movements and the level of real protest connected?

The available theoretical model, associated with the concept of discontent, differs from protest models, also exampled in literature. While protest as behaviour may be considered within the framework of works on the political participation, discontent as an attitude, can be equally well linked with the concept of political alienation [13]. A. Miller defines discontent as the feeling of powerlessness and lack of norms (two components of alienation), which is fastened by the attitude of the lack of confidence in the authorities, the hostility towards the leaders, institutions and authorities in the broad sense or feeling that the authorities are not working for the citizens [12, p. 951]. In this line of research two aspects of discontent are traditionally revealed, and the measurements are performed by means of the concepts of political effectiveness (powerlessness) and political (dis)trust or cynicism (lack of norms).

The explanations of discontent are also suggested in literature. On the one hand, some studies highlight the link between the basic characteristics (which act as the individual’s resource), such as age, income, education, group identification, and the level of political (in)efficiency, at that, higher level of resources is associated with the higher level of political effectiveness.

The data of the Vologda Oblast population monitoring allow confirming the presence of such connection ( tab. 2 ).

In addition, these data allows identifying the main characteristics of that part of the population, which is the bearer of protest moods. This group comprises, in particular, people with low purchasing capacity (“there is enough money only for food”), assessing the family’s financial position as poor, and what is obvious, negatively assessing their moods (“I feel stressed, angry, scared, depressed”).

However, most of the academic literature focuses on the impact of political discontent on participation, on the basis of W. Gamson’s assumption (“Gamson’s hypothesis”) that participation is best explained by the combination of trust and efficacy (feeling that active action is both possible and effective). The author claims that among people with strong sense of political efficacy, the suspicious are most likely to participate than the people, who trust: “More specifically, the combination of high political efficacy and low political trust is the optimum combination for mobilization – a belief that influence is both possible and necessary” [12, p. 48]. The main idea is that citizens with low degree of political efficacy will not participate in the protest, regardless of their level of trust, because they think that their participation will have no effect. Among people with high degree of internal political efficacy, the most trustful will participate less frequently because they are already satisfied with the system without any political involvement. Thus, people with low level of trust and high sense of political efficacy are more likely to participate in protest.

Table 2. The share of individuals with negative estimations in the groups of protest potential and among the rest of the population, %

|

2007 |

2007 |

2008 |

2008 |

2009 |

2009 |

2010 |

2010 |

2011 |

2011 |

2012 |

2012 |

10 month 13 |

10 month 13 |

|

Share of the population negatively estimating the country’s economic situation |

|||||||||||||

|

24.4 12.6 29.2 |

15.4 |

50.6 |

38.5 |

52.4 |

26.7 |

52.8 |

22.5 |

45.8 |

20.4 |

49.8 24.7 |

|||

|

Share of the population negatively estimating the oblast economic state |

|||||||||||||

|

24.3 11.6 27.4 |

15.2 |

52.3 |

40.3 |

55.7 |

28.7 |

54.9 |

24.1 |

50.8 |

24.0 59.0 31.2 |

||||

|

Share of the population negatively assessing the family’s financial position |

|||||||||||||

|

35.5 18.8 39.7 |

20.1 |

47.4 |

28.6 |

50.5 |

28.5 |

51.0 |

24.5 |

48.9 |

21.9 53.1 22.7 |

||||

|

Share of the population with low purchasing capacity (enough money for food at best) |

|||||||||||||

|

40.1 35.1 36.6 |

29.0 |

45.0 |

38.9 |

48.0 |

32.7 |

50.4 |

29.8 |

45.7 |

29.1 52.5 27.6 |

||||

|

Share of the population not approving the activities of RF President |

|||||||||||||

|

21.5 8.9 19.3 |

8.2 |

33.1 |

12.9 |

43.2 |

12.8 |

67.5 |

15.2 |

63.2 |

24.9 67.5 21.5 |

||||

|

Share of the population not approving the activities of Governor |

|||||||||||||

|

34.5 19.0 35.2 |

17.6 |

41.0 |

20.9 |

53.6 |

20.8 |

72.8 |

20.1 |

63.6 |

25.7 69.7 25.0 |

||||

|

Share of the population with negative assessment of moods |

|||||||||||||

|

42.8 24.6 39.6 |

23.7 |

48.3 |

24.7 |

53.8 |

27.7 |

52.2 |

23.2 |

47.6 |

21.9 50.7 21.4 |

||||

|

Source: ISEDT RAS monitoring data for 2007–2013. |

|||||||||||||

The concept of political efficacy caused much debate in literature. It was first proposed by A. Campbell et al. in the book “the Voter decides” [14] and has been used to explain a wide variety of the methods or modes of political participation. Four points of the survey, developed by A. Campbell, G. Almond and S. Verba in Survey Research Centre (USA) in 1964–1965, are mainly used to measure political efficacy. However, the reliability of the indicator turned out to be rather disputable. After several empirical tests the concept has been made more accurate by highlighting two separate aspects: subjective competence (internal efficacy), on the one hand, and the authorities’ ability to respond to the expectations and demands of people (“governmental responsiveness”) or external efficiency, on the other hand. Internal efficacy refers to a person’s sense that he is able to understand the policy and, therefore, enough competent to take part in political activities, while external efficiency is defined as the belief in the responsiveness of the authorities and institutions to the citizens’ demands. This concept was operationalized in various foreign studies, however, Russian researchers, in the authors’ opinion, are yet to separate various aspects of the efficiency and trust, to develop and test the items, which can be used to measure the internal and external efficacy, as well as diffuse and specific support. The authors believe that the Russian empirical studies, aimed at the description and explanation of political protest, so far ignore the key components, required for estimating the probability of the growth of the attitudes of discontent into protest behaviour, in particular the components of external and internal efficacy.

The operationalization of the political trust concept is also far from perfect.

According to A. Miller, political trust is “the basic evaluative or affective orientation toward the government” [12, p. 952]. W. Gamson defines trust as the diffuse support of the system in accordance with the widely-known David Easton’s classification of the types of support [10, p. 437]. Diffuse support (political trust) implies support, provided to institutions, in contrast to the specific support, which correlates with the support of particular persons. Specific support implies the utilitarian relationship between citizens and the authorities, while diffuse support will remain more stable over time.

The monitoring data allow analyzing this component of the protest syndrome among the Vologda Oblast residents.

It is obvious that the structures of both federal and regional level, in whose hands the real power and material resources are concentrated, receive the greatest support. The oblast population has the lowest level of trust in public organizations and political parties ( tab. 3 ).

The level of social trust in both state and public structures is observed to decrease, indicating the existence of deformation processes, which have affected the sphere of political life. The Vologda Oblast residents do not believe they can influence the government activities and thereby change their life for the better.

The society demonstrates high level of trust only in the President, however, even this mainstay of political trust has been diluted. This is the biggest risk for the regional authorities, which in such case lose support mechanisms necessary for pursuing economic and social policies, ensuring social stability in the region.

Economic well-being is an important factor, underlying trust. Economically prosperous social groups have trust in the institutions that secure such their position. The results of the analysis of the members of “the trustful” group show that it includes wealthy people, who are confident in the future, self-identifying themselves as rich and wealthy people, mainly middle-aged, mostly men, primarily executives and specialists. In fact, these features characterize the social group, which is called the middle class. It is the middle class that is considered to be the social force that forms the civil society [1].

As for other social groups, that have lost trust in the government agencies, first of all, it is “the new poor” [8], i.e. economically active people with higher or secondary education, identifying themselves as poor and needy, insecure about the future.

Table 3. Please, indicate your attitude to the social structures and government institutions, existing in the country (answer: “I trust”), as a percentage of the number of respondents*

|

Answer |

Vologda Oblast |

Russian Federation |

||||

|

2008 |

2012 |

2012 to 2008 +/- |

2008 |

2012 |

2012 to 2008 +/- |

|

|

President |

65.2 |

45.7 |

-19 |

62.3 |

49.0 |

-13 |

|

Church |

51.9 |

41.4 |

-11 |

47.0 |

53.5 |

+7 |

|

RF government |

60.2 |

39.6 |

-20 |

41.0 |

36.0 |

-5 |

|

Court |

41.3 |

36.1 |

-5 |

11.7 |

15.5 |

+4 |

|

Oblast administration |

48.6 |

34.6 |

-14 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Prosecutor’s Office |

40.9 |

33.9 |

-7 |

11.7 |

15.5 |

+4 |

|

Federal Security Service (FSB) |

43.8 |

33.2 |

-11 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Federation Council of the Russian Federation |

47.6 |

32.3 |

-16 |

22.7 |

25.5 |

+3 |

|

Army |

37.8 |

31.3 |

-7 |

43.7 |

47.5 |

+4 |

|

State Duma |

42.0 |

30.5 |

-11 |

17.0 |

20.0 |

+3 |

* In descending order according to 2012 results.

In addition to institutional (political) trust, the researchers bring forward the integrated interpersonal trust as an important factor for the transformation of discontent and protest moods to the real protest. Because the confidence in abstract systems cannot replace the significance of personalized trust, based on solidarity, sympathy, friendship, for the man. This type of trust becomes for the individual an alternative solution, in case he/she has to face “the distrust syndrome” (the term of the well-known Polish sociologist P. Sztompka) to the political regime, economic and social system in general, and guides him/her to traditional communities.

As follows from the survey results, about one third of respondents firmly believe that no one can be trusted (tab. 4). And half of the respondents are willing to trust only close friends and family. The obtained data indicates that the majority of the oblast population is strongly oriented at the inner circle community, above all, family. These data are to be fully correlated with the results of the answers to the question about people’s willingness to unite with each other, in order to protect their common interests (tab. 5 and 6).

The unwillingness to unite, self-isolation in the closed world of family and friends is a sort of indicator of the public distrust climate that exists in the regional community. The further destruction of social capital (different understanding of trust), which is an informal social attitude, based on choice and voluntariness, can lead to the weakening or loss of social identity.

Within the field of the protest research, the trust networks are the most likely channels for the mobilization of individuals for protest activities.

Table 4. Who can you trust?*, as a percentage of the number of respondents

|

Answer |

December 2011 |

February 2013 |

|

Nowadays no one can be trusted |

24.7 |

27.9 |

|

Only my most intimate friends and relatives can be trusted |

56.7 |

52.5 |

|

Most people I know can be trusted |

16.1 |

15.2 |

|

I trust each and everyone |

2.5 |

1.6 |

|

* The question was asked in December 2011 and February 2013. Source: ISEDT RAS monitoring data. |

||

Table 5. Are you willing to unite with other people for joint actions, in order to protect your common interests?*, as a percentage of the number of respondents

|

Answer |

2011 |

2013 |

|

I’m willing or rather willing |

25.2 |

19.9 |

|

I’m not willing or rather not willing |

25.2 |

37.1 |

|

Don’t know |

27.7 |

37.1 |

|

* The question was asked in December 2011 and February 2013. Source: ISEDT RAS monitoring data. |

||

Table 6. How would you assess your involvement in public and political life?, as a percentage of the number of respondents

|

Answer |

2011 |

February 2013 |

|

Active or rather active |

27.1 |

23.0 |

|

Passive or rather passive |

48.3 |

49.8 |

|

Don’t know |

24.6 |

27.2 |

|

Source: ISEDT RAS monitoring data. |

||

The apparent fragmentation of the elements of these networks is one of the reasons, for the impossibility of the attitudes of discontent to result in collective action.

However, it should be specified that the new types of communication and subsequent institutional networks have been emerging in the region. They are not widely-distributed, but they have already started playing the role of new channels mobilizing collective action. These include social networks, based on Internet technologies, first of all, Facebook, Twitter and Vkontakte, which, as demonstrated by international and Russian experience, can act quite effectively as the channels drawing into protest activities and broadcasting protest organizational innovations, thereby, expanding protest repertoire, used by different civil and political actors. American sociologist Charles Tilly defined protest repertoire as a set of various tools, used by the party for making demands to the other party [15; p. 18]. Repertoire, as a rule, inscribes social interaction in stable framework, acting both as a set of strategies and a cultural phenomenon. C. Tilly considered the repertoires of collective action in the long term, indicating that their changes occur very slowly. He made such statement shortly before the social network has become global and popular, and obviously, underestimated the diffusion rate of protest innovations that makes them possible.

In the period from December 2011 to 2012 autumn, in the course of the “new” protest wave, innovation alternative formats of the protest movement, previously uncharacteristic of Russia, proved to be quite in demand. First of all, these are flash-mobs, calling public attention due to their uniqueness and suddenness, motor races, “folk festivals”, “strolls of writers and artists”. As noted by Russian sociologist A. Zaytseva, “many activists indicate the ineffectiveness of such routine (traditional) forms, the need to constantly invent new attention-getting mechanisms.

At present, the protest does not exist, unless it is filmed, photographed and immediately posted on the Internet” [3]. This is the purpose of such popular international forms of political protest as encampment. Another Russian example is the action of the Russian non-systemic opposition camp Occupy Abay. Online protests have become a very specific protest form, including DDOS and other hacker attacks against the web-sites of political and public organizations, the Russian Government [6]. The infiltration of new protest technologies in the regions is at an early stage, however, the diffusion rate of innovation is high, and this tool of political confrontation and the channel of political mobilization is expected to be more widely used at the new stage of political development.

New trust networks give partial hope for the possibility to end the deadlock with regard to trust destruction and the collapse of traditional forms of collectivity. According to the authors, the expansion of the protest repertoire creates certain opportunities for “soft authoritarianism”, characteristic of modern Russia, to focus on gradual democratization.

However, new technologies have the destructive potential, as a result of the possibility of their use for the distribution of extremist anti-constitutional views, incendiary rumors, involvement to violent actions “in real”, etc.

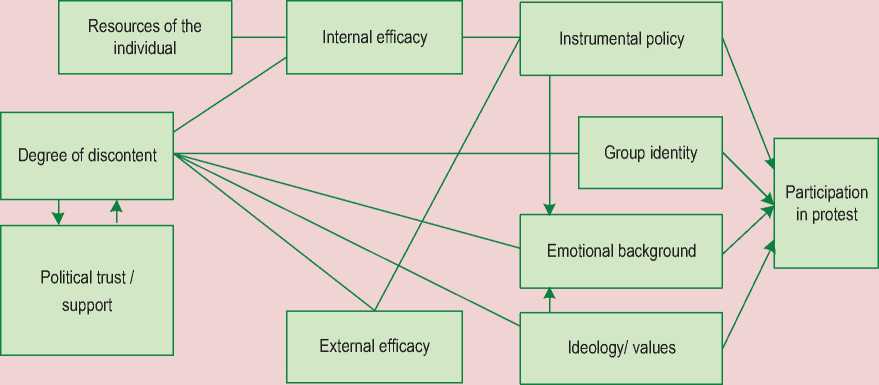

Let us draw up some cautious results. Despite considerable empirical data with regard to the description and explanation of protest behaviour of the Vologda Oblast (as well as all Russian) population, the authors suggest an integrated theoretical model coordinating different factors that create protest preconditions and transform these preconditions in protest ( fig. 2 ).

In this regard, the following issues remain relevant in theoretical and practical terms: firstly, what are the reasons for the formation of the attitudes of discontent, and secondly, what are the processes and factors leading to

Figure 2. Model of political discontent transformation in protest behavior

Geographical context

Context: Pollitical opportunity structure / Repressiveness of the regime/ Mobilization networks

the fact that the socio-psychological attitude of discontent is transformed into a real protest behaviour (or other behavioural response).

Logically we can assume that these factors include socio-psychological factors and the factors in social and political context.

The factors of subjective socio-psychological nature include instrumental calculations and considerations, based on the individual’s ability and capability to achieve goals, participating in protest movements (that is described in the concept of internal and external efficacy and resource model of participation ), the group identification factor, emotional factor (such as anger, solidarity, fear, pride), and finally, the ideological factor.

A number of researchers add political and cultural factors to this group, in particular, the existing specific system of the region’s population values. The role of this factor in the formation of protest behaviour is yet to be assessed.

External context is set by closed or open nature, “softness” or repressiveness of the regime (described by the theory of political opportunity structure), and the presence and efficiency of networks (channels) mobilizing for protest political participation.

The geographical context is important : social tension spills out faster and more graphically in large cities, such as Moscow, Saint Petersburg with the concentration of population several times higher2 than in some Russian regions, with higher living standards3, where the headquarters of the public organizations, the country’s government and parliament are located.

The political context is the result of four factors: the degree of access to the formal political structure, stability/instability of the political groups, the availability of the ideological position of potential alliance partners and political conflicts between elite.

The political opportunity is, obviously, a complex construct with several aspects, many of which are specific to certain types of the regime. On the whole, the political opportunities are also the factor restraining the consistent development of protest potential into the actual protest.

The practical task is to operationalise all conceptual model elements that will allow developing adequate tools for political and sociological survey and to implement the empirical verification of hypotheses on the relationship and the impact of protest behaviour factors for different social groups.

Список литературы Preconditions for the transformation of population's attitudes from political discontent to protest behaviour (as exemplified in the materials of ISEDT RAS, Vologda)

- Balabanova Ye.G. Middle class as the survey target of Russian sociologists. Obschestvennyye nauki i sovremennost’. 2008. No.1. P. 50-55.

- Weinstein G.I. Mass consciousness and social protest in the conditions of contemporary capitalism. Мoscow: Nauka, 1990.

- Zaytseva A. Spectacular protest forms in the modern Russia: between art and social therapy. NZ. 2010. No. 4(72). Available at: http://magazines.russ.ru/nz/2010/4/(Retrieved on November 25, 2013).

- Morev M.V., Kaminskiy V.S. Methodological peculiarities of studying social sentiment at the regional level. Problems of development of territory. 2013. No. 5 (67). P. 96-103.

- Our constitution: the history of interpretations and the perspective for modernization. Available at: http://www.politeia.ru/politeia_seminar/10/124 (Retrieved on November 21, 2013).

- Official web-site. Grani.ru. DDoS attacks. Available at: http://grani.ru (Retrieved on May 26, 2013).

- Hirschman A.O. Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Мoscow: Novoye izdatelstvo, 2009.

- Yaroshenko S. New “poverty” in Russia after socialism. Laboratorium. 2010. No. 2. Available at: http://www.soclabo.org (Retrieved on May 27, 2010).

- Bajoit, G. Exit, voice, loyalty.. and apathy. Les réactions individuelles au mécontentement -1988. No. 2. Vol. 29. P. 325-345.

- Easton D. A Re-assessment of the concept of political support. British journal of political science, 1975. 5(04). P. 435-457.

- Gamson W A. Power and discontent. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press, 1968.

- Miller A. Political issues and trust in government: 1964-1970. American political science review. 1974. Vol. 68 (September). P. 951-972.

- Olsen M. Two categories of political alienation. Social forces. Vol. 47. No. 3 (Mar., 1969). P. 288-299.

- Campbell A., Gurin G., Miller W.E. The voter decides. Evanston, Ill.: Row, Peterson and Co. 1954.

- Tilly С. Regimes and repertorires. The Univ. of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Gulin K.A., Dementieva I.N. Main tendencies of protest moods in the Vologda Oblast. Sociological surveys. 2008. No.11. November. P. 64-71.