Reproductive attitudes of young families: driving forces and implementation conditions (on the basis of in-depth interviews)

Автор: Korolenko Aleksandra V., Kalachikova Olga N.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.15, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Promoting population reproduction is one of the key tasks from the standpoint of ensuring national security. In the conditions of aging motherhood, the young family becomes the most important object of demographic policy, since it is a prosperous two-parent family with children that is the main resource of quantitative and qualitative parameters of human capital. The article analyzes reproductive attitudes of young families and the drivers of their implementation. We reveal that, on average, young people are focused on creating a family and having few children. The registered failure to fulfill reproductive intentions (the desired number of children is more than their expected number) is due to the financial and economic situation of the family, the uncertainty (possible risks) of the future, and intra-family relations. The formation of young people's reproductive attitudes largely depends on their parents' example, the quality of child-parent relations and the immediate environment. With a high probability, those raised in a family with few children or those who have no siblings at all may not want to have many children or have children at all. As for children from medium and large families, they may have different views on having children. Reproductive attitudes are linked to marital ones. As a rule, the orientation toward a legitimate happy marriage is reinforced by the desire to have children. A variant of child-centered motives is observed in girls and manifested in the desire “to have a big family and many children”, which somewhat shifts the focus of the priority of intra-family relations. The importance of the housing issue and ensuring a decent standard of living for oneself and one's children is determined by the fact that the unresolved nature of these problems influences the intention to have the first child and reduces the chances of having a few and many children even if they are desirable. State support for young families is needed, despite differences in the estimates of its effectiveness. The difference lies in determining the most desirable mechanisms - it is either direct support in the form of allowances, benefits, etc., or the creation of conditions for raising children (affordable quality social infrastructure) and the possibility of decent earnings for parents. Today, a young family needs state support, and, undoubtedly, the needs of young families should be taken into account in the national demographic policy.

Young family, reproductive attitudes

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147238038

IDR: 147238038 | УДК: 314.375+316.356.2 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2022.2.80.11

Текст научной статьи Reproductive attitudes of young families: driving forces and implementation conditions (on the basis of in-depth interviews)

In 2020, the natural decline in the population of Russia exceeded 700 thousand people and was almost twice as high as in 2019 (317.2 thousand people), approaching the scale of natural decline in the early 2000s. Compared to 2014, when the highest fertility rates in the last two decades were recorded, in 2020 the total number of births decreased by more than 500 thousand, and the total fertility rates fell from 1.8 to 1.5 children per 1 women of reproductive age. At the same time, there is a tendency toward aging of motherhood: the average age of a mother at first birth in Russia rose from 25.8 in 2000 to 28.8 in 2020 (Shabunova et al., 2021).

Young families are recognized as an important “demographic reserve” in terms of solving demographic problems (Chernova, 2010). Thus, within the framework of the Concept of state policy on the young family, approved by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia in 2007, a young family was singled out as a special type of family, in relation to which state policy should be conducted1. The provision of state assistance to young families was subsequently included in the list of tasks of the Concept of State Family Policy for the period through to 2025, approved in 20142, and directions for the implementation of youth policy, reflected in the Federal Law of the Russian Federation “On youth policy in the Russian Federation”, adopted in 20203.

Among the specific features of young families, researchers emphasize the instability of intra-family relations (high divorce rate), mastering new social roles (spouses, parents), specific problems – financial and housing, increased financial needs in connection with the formation of family life, including the need to purchase their own housing and set up home (Chernova, 2010; Rostovskaya, 2014). The vulnerable position of young families, both in terms of financial situation and marital stability, on the one hand, and their high demographic potential, on the other, make the study of young families’ attitudes toward having children and the factors determining them necessary and urgent.

The purpose of our study is to examine the reproductive attitudes of young families and to identify factors and conditions of their realization based on the results of a series of in-depth personal interviews with representatives of this category of families. This type of qualitative sociological research makes it possible not only to assess the reproductive attitudes and plans of young families, but also to identify their underlying factors and preconditions, including the life experience of the family of origin, to explain the “origins” of reproductive behavior formation (Rostovskaya et al., 2021c).

Theoretical aspects of the study

Approaches to interpreting the concept of “young family”. As Zh.V. Chernova notes, the concept of “young family” is not used as an independent category in Western sociological literature. Analysis of the socio-psychological and economic problems that spouses face in the early years of family life, as a rule, is carried out in the study of the stages of the family life cycle or family life course. Different models of social policy in Western countries also do not operate with this category and do not consider a young family (a couple where the age of the spouses does not exceed 30 years old) as a special object of social and family policy (Chernova, 2010). In view of this, we turn to the Russian experience of allocating criteria for defining a young family.

The category “young family” is most often used in studies in the field of sociology of family and demography, social psychology and pedagogy, as well as in strategic, containing a program of action and other normative legal documents that regulate issues of socio-demographic, family and youth policy. The common criteria for all established approaches to the interpretation of a young family are the fact of registered marriage and the age of the spouses (Tab. 1). Most often the upper age limit for young family members is 30 years, but for participants in housing programs it is higher and reaches 35 years (Rostovskaya, 2014).

A number of researchers-demographers, sociologists and educators, some state documents reflecting the tasks of youth policy, such as the “Main directions of state youth policy in the Russian Federation”, dated 1993, designate the length of time the spouses have lived together as a mandatory criterion for young families. In the works of Russian sociologists E.M. Zuikova and N.V. Kuznetsova, as well as in the directions of state youth policy in the Russian Federation, the duration of young spouses’ cohabitation is limited to three years. However, in families with children the duration of marriage is not taken into account. Other researchers define the duration of spouses’ cohabitation in a young family as up to 5 years.

Some scholars consider that the criterion for defining a young family is the order of marriage , namely the fact that both young spouses are in their first marriage (T.K. Rostovskaya, T.A. Gurko, M.S. Matskovskii, I.V. Grebennikov, L.V. Kovin’ko, E.M. Zuikova, N.V. Kuznetsova, I.P. Katkova).

It is noteworthy that conceptual and other normative legal documents additionally stipulate criteria for the composition of young families based on the presence of a married couple (single- or two-parent family) and parenthood status of the family, which is probably related to the definition of those who need support.

In our study, a young family is defined as a family in which both spouses are under the age of 35, are in their first officially registered marriage, have a child (children) or plan to have them.

Research on the reproductive attitudes of young families. In Western countries, research on reproductive attitudes is conducted within the

Table 1. Approaches to defining a young family

|

Criteria |

Definition of a young family |

Author(s), sources |

|

Marital relations of young people in the first 5 years of cohabitation. |

B.Ts. Urlanis |

|

A family with up to 5 years of marriage and the age of the spouses not exceeding 30 years |

A.I. Antonov |

|

|

A family where the spouses are in their first registered marriage, the age of each spouse or one parent in a singleparent family does not exceed 30 years (for participants in housing programs to support young families, the age of the spouses increases up to 35 years) |

T.K. Rostovskaya |

|

A family with up to 5 years of cohabitation, where the spouses are under 30 years of age and are married for the first time |

T.A. Gurko, M.S. Matskovskii, I.V. Grebennikov, L.V. Kovin’ko |

|

Families with up to 3 years of cohabitation, where both spouses are in their first marriage and have not reached the age of 30 |

E.M. Zuikova, N.V. Kuznetsova |

|

|

Families with no more than 5 years of marriage, in which both spouses are no older than 29 and both are in their first marriage |

I.P. Katkova |

|

(single- or two-parent family)

|

Families in the first three years of marriage (in the case of the birth of children – without limiting the duration of the marriage), under the condition that one of the spouses has not reached the age of 30, as well as single-parent families with children whose mother or father has not reached the age of 30 |

The main directions of state youth policy in the Russian Federation (ceased to be in force on January 10, 2021)* |

|

A full family, where the age of each spouse does not exceed 30 years, or a single-parent family consisting of one young parent under 30 years of age and one or more children |

The concept of state policy for the young family** |

|

A young family, including those with one or more children, where the age of each spouse or one parent in a single-parent family does not exceed 35 years |

Federal targeted program “Housing”. Subprogram “Providing Housing to Young Families”*** |

|

|

Persons who are married in accordance with the procedure established by the laws of the Russian Federation, including those who are raising a child (children), or a person who is a single parent (adoptive parent) of a child (children), under the age of 35 years inclusive. |

Federal Law “On Youth Policy in the Russian Federation”**** |

|

|

A family in which both spouses are under 30 years of age, as well as a single-parent family with children in which the mother or father is under the age of 30 |

S.B. Denisov |

framework of the theory of planned behavior , the foundations of which were laid in the works of Ajzen and Fishbein (Ajzen, Fishbein, 1980). The population’s attitudes toward having children (or so-called reproductive intentions) are often seen as inextricably linked to actual fertility (Coombs, 1979; Westoff, 1990; Bongaarts, 2001; Morgan, 2001; Morgan, Rackin, 2010; Testa et al., 2011; Philipov, 2009).

The main approach to the study of reproductive attitudes in Russian sociology and social demography is the concept of the family’s need for children4 (Borisov, 1976; Darskii, 1972; Darskii, 1979; Sinel’nikov, 1989; Arkhangel’skii, 2006). Under reproductive attitudes within this approach, we understand the mental states of a person, which condition the mutual coordination of different kinds of actions, characterized by positive or negative attitudes toward having a certain number of children5. The need for children is numerically expressed through a system of three indicators – the ideal, desirable and expected number of children. The ideal number of children is the cognitive component of the reproductive attitude (orientation to social norms), the desirable one is the cognitive-emotional component, the expected one is the practical component (Borisov, 1976). Similar indicators are used in foreign studies of reproductive intentions, but the former is the most criticized. For example, according to the Dutch demographer D. Van de Kaa, the ideal number of children is more abstract, so it is poorly related to the actual experience of having children (Van de Kaa, 2001). The indicator of the desired number of children best reflects the individual need for children, but is recognized as a weak predictor of real fertility, because preferences regarding the desired number of children can change over the course of life (Van Peer and Rabusic, 2008; Heiland et al., 2008). In low-fertility countries, the desired number of children will always be greater than the actual number, with little variation between the two (Tyndik, 2012). The indicator of the expected number of children is recognized as more stable and reliable both by foreign (Philipov, 2009) and Russian researchers (Andreev, Bondarskaya, 2000). As A.O. Tyndik notes, reproductive attitudes, measured through the desired and expected number of children, in countries with fertility below population replacement level (which includes Russia) set the upper limit of actual fertility (Tyndik, 2012).

Reproductive attitudes of young families within the framework of Russian demography were studied at different times by A.G. Volkov (Volkov, 1986), V.A. Belova and L.E. Darskii (Belova, Darskii, 1972; Belova, 1975; Darskii, 1979), V.A. Borisov (Borisov, 1976), A.G. Vishnevskii6, V.N. Arkhangel’skii (Arkhangel’skii, 2006), A.O. Tyndik (Tyndik, 2012) and others, within the framework of family sociology by A.G. Kharchev (Kharchev, 1979), S.I. Golod (Golod, 1998), M.S. Matskovskii and T.A. Gurko (Gurko, 1985; Matskovskii, Gurko, 1986a; Matskovskii, Gurko, 1986b), A.I. Antonov and V.M. Medkov7, V. Zotin (Zotin, Mytil’, 1987), (1987), I.F. Dement’eva (1991), I.P. Mokerov and A.I. Kuz’min (1986a; Kuz’min, 1986b; Mokerov, Kuz’min, 1990; Kuz’min, 1993), A.V. Poimalov8 et al.

Driving forces of young families’ reproductive attitudes. The analysis of Russian studies on the determination of the reproductive attitudes of young families allowed combining the factors contributing to reproductive preferences into five groups (Tab. 2) .

Table 2. Driving forces of young families’ reproductive attitudes in Russian studies

|

Roup of factors |

Factor |

Researchers |

|

Marital and family characteristics of the family of origin |

Example of a family of origin, in particular the number of children |

T.E. Safonova, I.Yu. Rodzinskaya, O.V. Grishina, I. Osipova |

|

The nature of the relationship between family members, common family values |

A.I. Kuz’min, A.I. Antonov, A.V. Zhavoronkov, S.I. Malyavin, T.V. Kuz’menko |

|

|

Value orientations of spouses |

Values of family and marriage, children and parenthood (including the relationship between family values (marriage, children) and non-family values - self-development (education, career), leisure, financial well-being, personal freedom) |

A.I. Antonov, A.B. Sinel’nikov,

N.V. Zvereva, and S.N. Varlamova, A.V. Noskova, N.N. Sedova |

|

Socio-demographic characteristics of a young family (spouses, children) |

Territory of residence (urban/rural) |

L.E. Darskii,

I. Osipova, V. Zotin, and A. Mytil’, G.F. Kravtsova, M.V. Pleshakova, V.N. Arkhangel’skii, A.O. Tyndik |

|

Age of spouses (age difference) |

||

|

Education level of spouses |

||

|

Ethnicity of the spouses |

||

|

Religion |

||

|

Number and gender of existing children |

||

|

Matrimonial Behavior and Family Stability |

The nature of the relationship between spouses and marital satisfaction, family stability |

A.I. Kuz’min, V.N. Arkhangel’skii, M.S. Matskovskii, T.A. Gurko |

|

Age of marriage |

I.P. Katkova, V.A. Belova, L.E. Darskii, V.L. Krasnenkov, N.A. Frolova, V.N. Arkhangel’skii |

|

|

Attitudes toward marriage registration |

||

|

Socio-economic status of the family |

Standard of living of the family |

I.P. Katkova, A.I. Kuz’min, G.F. Kravtsova, M.V. Pleshakova, E.M. Andreev, G.A. Bondarskaya and T.L. Khar’kova, V.N. Arkhangel’skii, T.K. Rostovskaya, E.N. Vasil’eva |

|

Living conditions of the family |

V.M. Dobrovol’skaya, I.P. Katkova, V.N. Arkhangel’skii |

|

|

State socio-demographic and family policy for young families |

V.N. Arkhangel’skii, N.G. Dzhanaeva, T.K. Rostovskaya, O.V. Kuchmaeva, T. Maleva, A. Makarentseva, E. Tret’yakova, A.A. Shabunova, O.N. Kalachikova, I. Osipova, E. Borozdina, E. Zdravomyslova, A. Temkina |

Source: compiled according to (Safonova, 1982; Rodzinskaya, 1986; Grishina, 2008; Osipova, 2020; Kuz’min, 1986a; Antonov et al., 2005; Kuz’menko, 2010; Arkhangel’skii, 1987; Arkhangel’skii; 2006; Arkhangel’skii et al., 2005; Varlamova et al., 2006; Medkov, 1986; Belova, Darskii, 1972; Zotin, Mytil’, 1987; Kravtsova, Pleshakova, 1991; Tyndik, 2012; Kuz’min, 1986b; Kuz’min, 1993; Gurko, 1985; Matskovskii, Gurko, 1986b; Katkova, 1971; Katkova, 1973; Krasnenkov, Frolova, 1984; Kravtsova, Pleshakova, 1991; Andreev et al., 1998; Arkhangel’skii et al., 2021; Dobrovol’skaya, 1974; Arkhangel’skii, Dzhanaeva, 2014; Rostovskaya et al., 2021a; Maleva et al., 2017; Shabunova, Kalachikova, 2013; Borozdina et al., 2012); A.I. Antonov. (2021). Similarities and differences in the value orientations of husbands and wives according to the results of a simultaneous survey of spouses . Moscow: Pero.

One driving force in the reproductive attitudes of the Russian population that requires consideration is the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite the novelty of this issue and its incomplete study, the available Russian studies confirm the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the reproductive plans of Russians, expressed, in particular, in postponing having children by the young population (under the age of 35), which threatens to reduce the final birth rate (Makarentseva, 2020). This also confirms N.E. Rusanova’s opinion that socio-economic uncertainty during the pandemic forces couples to postpone any long-term investments, of which children are a prime example, and thus further to reduce fertility (Rusanova, 2020).

Methodological aspects of the study

Studies of the population reproductive attitudes are carried out by quantitative and qualitative sociological methods. Quantitative surveys are used, for example, in the framework of population censuses (Microcensus 20159) and sample surveys of the Federal State Statistics Service (for example, sample surveys of reproductive plans in 201210 and 201711). The family and fertility sample surveys in 200912, one-time and multi-year (monitoring) sociological surveys of the population (for example, “Parents and children, men and women in family and society” of HSE University13). There are also a number of qualitative methods for studying reproductive attitudes and their factors, such as focus group studies (Gudkova, 2019) and in-depth interviews (Shabunova, Kalachikova, 2008; Ipatova, Tyndik, 2015; Zhuk, 2016).

According to the results of the first wave of the all-Russian sociological survey “Demographic wellbeing of Russian regions”, conducted by mass questionnaire survey in late 2019 – early 2020 (the total sample size was 5,616 people), we studied the reproductive attitudes of the population, including its different socio-demographic groups. (Rostovskaya et al., 2021d).

The article presents the results of the second stage of the all-Russian sociological survey “Demographic well-being of Russian regions” conducted in 2021 in the framework of the project no. 20-18-00256 “Demographic behavior of the population in the context of national security of Russia” with the support of the Russian Science Foundation.

Research method – in-depth personal interview (method of selection of informants – purposive, method of “snowball”). The sample design (purposive method of selection) was carried out by recruiting informants through social networks (both personal social relations and Internet communities in social media) (Rostovskaya et al., 2021b). We sampled young families in which both spouses are under the age of 35, married, and are planning to have children. We interviewed 17 informants in the republics of Bashkortostan and Tatarstan, the Volgograd, Vologda, Ivanovo, Moscow, Sverdlovsk, and Nizhny Novgorod oblasts, and Stavropol Krai.

All informants were from wealthy families, regardless of their social and professional background (the level of wealth of the informants was median for the region). We conducted the analysis using the research questions reflected in the guides for this group of informants with a parallel search for possible regional differences.

Main results and their discussion

According to the data of the first wave of the allRussian sociological survey “The demographic wellbeing of Russian regions”, among married young

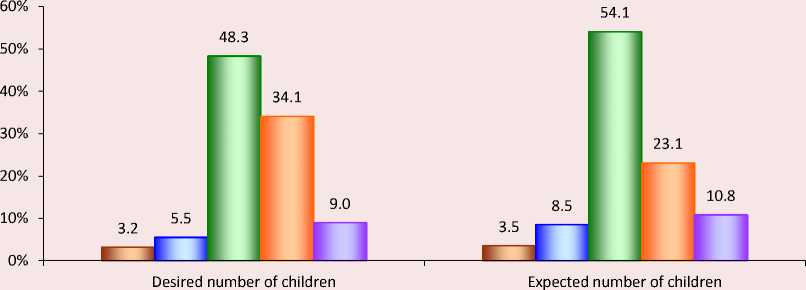

Distribution of answers of young married respondents (17–29 years old) about the desired and expected number of children, %

□0 □1 □2 □ 3 and more □ hard to say

Source: Data from the all-Russian sociological survey “Demographic well-being of Russia”, 2020 (N = 351).

respondents (17–29 years old) both in terms of the desired (i.e. if all the necessary conditions are available) and the expected (actually planned) number of children, the attitude to have two children prevails (Figure) . However, while every third family respondent aged 17–29 years old expressed a desire to have three or more children (34%), only 23% of representatives of this category actually plan to have many children, which indicates serious barriers to fulfilling of the need for having many children. While the proportion of those who plan to have few children is 9 percentage points higher than in the case of those who want to have 1–2 children even if they have the necessary conditions (63% vs 54%).

According to the data of in-depth interviews, two types of reproductive attitudes (plans) are found among young family respondents: those who want few children (having 1–2 children) and many children (having 3 or more children).

Some of the informants who plan to have few of children (1–2 children) admit that, given all the necessary conditions (desired number of children), they would like to have more children in the family, which indicates the initial need for having many children.

– “We are planning to have two or more children if opportunities allow and if there are no adverse health indications. But I think not one. Because then maybe the child will grow up to be selfish...” ( male, 22 years old, married, no children (about to have a baby), 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast );

– “The ideal number of children for us is two. If we had everything we needed, we would like to have three children” (female, 22 years old, married, no children, 4 children in the family of origin, university student, the Moscow Oblast) ;

– “Well, I would like to have two. We are open to have children, but we’ll see whether there will be opportunities for this. Three children, yes, we would like to” (note – “if we made more money and had a two-bedroom apartment”) (male, 32 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, unfinished higher education, Republic of Tatarstan) .

Another part of the informants with attitudes to having few children are not ready to change their plans, even provided all the necessary conditions for having more children:

– “If we had everything we needed, we would want to have at least two children. To give our children everything, we still need financial wherewithal, so in order not to limit the children in anything, two children would be an ideal solution” (female, 30 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast);

– “Well, I think at least have one baby first and see how you feel... I mean, whether you are comfortable with one child. And again, if health allows having more children, why not? And the image of the perfect family is like that TV advertising with a happy family – a boy, a girl and that’s it” (female, 26 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast) .

Analysis results of in-depth interviews revealed the correlation of reproductive attitudes of young families with the following factors: the example of the family of origin, including the number of children, matrimonial behavior of spouses and their attitude toward marriage, combining career and parenthood, measures of state socio-demographic policy, housing and financial conditions, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Let us dwell on each of them in more detail.

Matrimonial behavior and attitudes toward marriage

It is noteworthy that those informants who initially (since childhood) dreamed of marriage and family more often have reproductive attitudes toward having many children and do not postpone it:

– “Well, I dreamed, like all little girls, that I will have a good family... <...> we want about two or three children, but wait and see” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 3 children in the family of origin (half-brother and -sister), university student, Republic of Bashkortostan) ;

– “Yes, since childhood I have dreamed of getting married in a beautiful white dress... <...> As for children, I plan to have two or three, depending on the work, earnings, and financial situation... I love children very much. I want a lot of children and I hope it will come true” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast);

– “I dreamed of marriage... We wanted and still want to have two or three children” (male, 22 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, the Moscow Oblast) .

However, according to the answers of other respondents, child-centrism can be traced. Thus, the initial attitudes toward having a family and many children are not necessarily combined with attitudes toward marriage:

– “...I haven’t dreamed of marriage in and of itself. I didn’t have such a goal to get married as soon as possible... I’ve had a very reverential attitude toward children since I was a kid. I’ve always been very fond of children, nursing nephews, brothers, sisters, whoever I could. Always wanted a big family. My husband and I are planning at least three children” (female, 22 years old, married, 1 child, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, Stavropol Krai) ;

– “In fact, I did not have such a thing that from an early age I dreamed of a white dress, of a prince on a white horse. No, there was no such thing… Of course, I really want to have children. You never know, but I would like to have three children. I believe that every woman should become a mother, to continue her family line. I have a very positive attitude toward it, and I think it’s everyone’s duty” (female, 24 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, the Volgograd Oblast) .

Example of a family of origin

Of great importance in the formation of marriage and family and reproductive attitudes in young spouses are relationships in the family of origin and a positive image of the parents’ marriage, as well as close relatives (grandparents). Even divorced parents could set an example of a happy family and instill family values in their children:

– “My parents are divorced. They didn’t get on... <...> They understood happiness as love, family values, family well-being... <...> They took good care of us. Spent time with us, watched movies together, went for walks in nature, went to sea” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast) .

When building their own family, including when planning to have children, respondents are guided by a positive model of marital and family behavior of parents and close relatives:

– “We are used to living in a friendly environment with a large number of people. And we wanted a big family, too. And from about the age of 16 we planned that we wanted six children. My grandfather was the first child in a family of nine children. My wife’s grandmother also came from a family with 9 children, but not all of them lived to adulthood. In my grandfather’s family, everyone lived to adulthood” (male, 20 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, Republic of Bashkortostan) ;

– “I dreamed of marriage. More along the cliche lines of my parents’ family. That’s probably how it turned out. We are happy and focused on having children. I hope the marriage will be strong and prosperous” (male, 22 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, the Moscow Oblast) ;

– “I’ve always wanted a big family. My husband and I are planning at least three children... Naturally, like any other woman, I always dreamed of being a good mother to my children. For me, the example is my mother, who raised my brother and me. I take a lot from her, I remember how we grew up in the family, how our parents treated us, and I try to give my child the best of everything, not without my husband’s help, of course” (female, 22 years old, married, 1 child, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, Stavropol Krai) .

Number of children in the family of origin

As the data from in-depth interviews showed, the only children in the family more often have reproductive attitudes toward having few children (1–2 children) and are more oriented toward postponing it:

-

- “Yes, we discussed (note: how many children they want and when they will have them). Together we’ve decided that it was too soon. My spouse supports me in this opinion, we are unanimous on this point... <…> We would like to have one or at most two children, I think that is the optimal number” (male, 23 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast) ;

– “Yes, we discussed and agreed that first you need to establish your life, the quality of life more or less, and then think of having children. Well, first we’ll give birth to one, and then we’ll see. How can you, let’s say, want two or three children, maybe you’ll have one, and you won’t like it... I’m 26 now, at 28 I’ll probably think of it. If we don’t solve the problem with the apartment and the repair by 30, we won’t have time for anything, or something will go wrong, we’ll probably have to... Well, in general, you have to take your health condition into account. Someone at 35 gives birth successfully, someone at 20 – not so easily” (female, 26 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast) .

-

Conditions for the realization of reproductive attitudes

The main conditions necessary for having children in the answers of almost all young family respondents, especially men, are financial well-being and availability of housing:

-

– “I’d like to earn enough; I’m making my plans on how to achieve that. To have enough of everything. To improve my financial situation, so that I could afford to buy myself a stroller, for example, which costs 25,000 rubles” (male, 20 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, Republic of Bashkortostan) ;

-

- “The main condition is financial prosperity, to be able to provide the child with everything they need, medical care, education, development, recreation, since most of these services are now chargeable. Of course, it is also important to have a place of your own, so you don’t have to move to a rented apartment with your child...” (male, 23 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast) ;

– “The first condition is own housing, as well as the financial situation” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast) ;

– “It all comes down to one thing – I would like to make a decent living. To have a nice house, a good car, opportunity to give a good education. It all comes down to one thing: finances” (male, 22 years old, married, no children (about to have a baby), 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast) .

At the same time in the answers of some representatives of young families the housing factor was recognized as a key factor in making the decision to have a child:

– “Right now, we’re living in a rented apartment, so to speak. We don’t have our own, the plan is to buy our own place first, to give the child their own roof over head” (male, 32 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, unfinished higher education, Republic of Tatarstan) .

In addition, in some cases, the main condition for having a child is the certainty of the family’s place of residence. The main limiting factor here is the spouse’s occupation, which is associated with frequent changes of residence (or the itinerant nature of work, or a member of the armed forces):

– “Yes, we are planning children, we want to, but due to my spouse’s work and the fact that Vologda is not our final destination, we don’t know how it will turn out yet... <…> We would like to finally decide on the place of residence, since the birth of children is a certain attachment to kindergarten, school, arrangement of the house for the children, we would like to finally decide where and when we will stay” (female, 30 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast).

Among other things, young spouses named intra-family factors as conditions for the birth of children. These include the state of health, psychological readiness to have children, the parents’ moral character (responsibility, absence of deviations), and the nature of spouses’ relationship (mutual understanding):

– “Besides that, I guess, a woman should be in good health, to carry a child, and psychological maturity is important, while I still feel that I’m not ready to have children” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 3 children in the family of origin (half-brother and -sister), university student, Republic of Bashkortostan) ;

– “…the moral adequacy of the parents. An understanding of responsibility both for each child and for the family as a whole. The absence of any factors that exclude social irresponsibility in order to reproduce offspring, i.e. alcoholism, drugs, gambling and other addictions” (male, 25 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast) .

External factors such as the availability of medical facilities, good environmental conditions, assistance from parents (not only financial), and crisis phenomena in the country are also significant conditions for young families to have children:

– “I would like to have housing near the forest, so that there would be clean air, and to have medical facilities nearby... Of course, we still need the help of parents. We don’t have any experience, and parents can share theirs” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast) ;

In addition, some informants noted the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their reproductive attitudes and expressed their willingness to reconsider their plans to have children because of the worsening situation or have already postponed pregnancy because of health risks to the child, fear of getting infected, and the suspension of elective care during lockdown and self-isolation:

– “The pandemic has affected us only in the sense that there are risks of getting infected. And we don’t know how the virus will affect the child, so we’re still waiting for all this to be over, at which point we’ll move” (female, 30 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast) ;

– “Not for now, although we don’t know what will happen next (note: about the impact of the pandemic). I think it won’t affect us. But if this situation continues, we’ll have to postpone it, because it’s scary” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast) .

State socio-demographic policy

In relation to the measures of state sociodemographic policy, informants had different opinions, which can be divided into three groups. The first group is young families who do not count on government assistance, relying only on the self:

– “We still try to be on our own, because the laws change very often. Now the maternity capital is paid even for the first child, and it is possible that when we have a baby it will no longer be paid, that is, we are ready for this, we are not going to give birth sooner, just to get the maternity capital. We’re trying to rely more on ourselves, though” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 3 children in the family of origin (half-brother and -sister), university student, Republic of Bashkortostan) ;

– “I don’t think you should count on government help. Of course, it would be good if there were help and support from the authorities, but we have to rely primarily on ourselves, which is why we are in no hurry to have a child” (male, 23 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast).

The second group is young families who rely on state assistance, but its measures do not influence their decision to have children, being only a “bonus”:

– “In my opinion, parents should have children for themselves. Accordingly, it does not matter what state support measures will be offered to you if you want to have a child, if you are willing to support him or her. Yes, it’s certainly not a bad bonus when having children, because finances are required anyway, but that’s not the most important thing” (female, 30 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast) ;

– “I’m counting on maternity capital. No, they do not affect (note: about whether state/regional support measures will affect the decision to have children)” (female, 24 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, the Sverdlovsk Oblast) .

The third group is young families who count on state assistance and recognize the influence of measures on their decision to have children:

– “Well, I know about some of the allowances and benefits from the state and when I get close to having a child, I’ll go deep into that and count on it. Yes, I think any movements and help from the state on this issue helps to encourage to have a child” (male, 23 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin (half-brother), university student, Sverdlovsk Oblast) ;

– “Yes, if there were any benefits for young families, young parents – we would not refuse. I think they will have an impact; it will be easier financially. I think that if there is support from the state, it will be possible to have more children” (female, 21 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student, the Ivanovo Oblast.) .

The most well-known measure of state support among young family respondents is maternity capital – almost all respondents are informed about it (including the terms of its provision). The main uses of maternity capital, according to informants, are to improve living conditions , in particular, to make a down payment on a mortgage, as well as the education of children :

– “Maternity capital is in any case an investment in the future of children, part of the repayment of mortgages or the education of children” (female, 30 years old, married, no children, the only child in the family of origin, higher education, the Vologda Oblast) .

Attitude toward balancing career and parenthood

Young families have two attitudes toward balancing a career and parenthood . Some believe that children are not a hindrance to a career:

– “Well, like, I want to build a career. Probably get some other education, maybe open some business, or kind of stay in the military... A child is not a hindrance to a career if there is someone to help, say, for instance parents, grandparents. Maybe for a while career can be interrupted, but during pregnancy, you can develop yourself, well, in general, pregnancy, children are not an obstacle” (female, 22 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, university student + is working, Stavropol Krai) .

Other informants, on the other hand, recognize the influence of having children on career development: “Yes, it just pulls away (note: career development) ... affects, appropriately, only in terms of the time factor. One child pulls back your career opportunities by two years. I mean ... if a man babysits, it affects a man’s career, if a woman, it affects a woman’s career” (male, 25 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin, higher education, the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast). At the same time, some informants have high hopes for family (parents) to help them raise their children during their careers: “I plan to work and develop as a specialist, to conquer new markets, new heights in my field and earn even more, these are my professional plans. Of course, I count on my parents, that is, my mother and mother-in-law, on their help in caring for and raising the child, and I hope to make time for it myself” (male, 23 years old, married, no children, 2 children in the family of origin (half-brother), university student, Sverdlovsk Oblast).

Discussion

The results of the study largely agree with those obtained earlier. For example, a survey of unmarried young people in the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast shows a connection between marital and reproductive attitudes. Its results show that those who hold the view that it is advisable to postpone marriage registration for a year or two have a lower number of children, both desired and expected. Women who believe that marriage registration should precede the beginning of marital relations had a significantly higher average expected number of children (Arkhangel’skii, 2006). Other studies prove the weakening role of officially registered marriage in the birth of children (Mitrofanova, 2011).

A.I. Kuz’min (Kuz’min, 1986a), A.I. Antonov, A.V. Zhavoronkov and S.I. Malyavin (Antonov et al., 2005), T.V. Kuz’menko (Kuz’menko, 2010) make conclusions about the positive influence on reproductive attitudes of good relationships in the family of origin and instilling family values. Many Russian studies also show that respondents have relatively higher reproductive orientations when there are more children in the family of origin (Safonova, 1982; Rodzinskaya, 1986; Grishina, 2008; Osipova, 2020). At the same time, the results of a survey in the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast showed that even given all the necessary conditions, on average people would like to have fewer children than their parents intend to have and actually have (Arkhangel’skii, 2006).

V.N. Arkhangel’skii analyzing the data of the first wave of the All-Russian monitoring “Demographic well-being of Russian regions” points out the ambiguity of the connection between the number of children in the family of origin and the reproductive orientations of young people: respondents whose family of origin had two, three or four children had no significant differences in either the desired or the expected number of children (Rostovskaya et al., 2021a).

The results of in-depth interviews with representatives of young families correlate with the data of the first wave of the all-Russian sociological survey “Demographic well-being of Russian Regions” and the importance of demographic policy measures, namely in terms of solving the housing problem: 60% of married respondents aged 17–29 years rated assistance in obtaining housing most highly. The importance of maternity capital for improving the housing conditions of young families has been confirmed in a number of Russian studies (Borozdina et al., 2012; Osipova, 2020).

However, housing conditions and living standards primarily influence the decision on having children, and it is this that differentiates the expected number of children. For example, according to the surveys in Moscow and the Samara Oblast, a direct link between the assessment of living standards and living conditions and the expected number of children is primarily applicable to those who would like to have three or more children under the most favorable conditions (Arkhangel’skii, 2006).

The underestimation of the population policy role may be related to the perception that people make decisions in their lives regardless of any external circumstances (Arkhangel’skii, Dzhanaeva, 2014). When deciding whether or not to have a child, people are guided by personal motives (Osipova, 2020).

Young people showed a greater response to pandemic risks. As Makarentseva’s research shows, the proportion of young respondents who prefer to postpone childbearing for financial reasons increased more strongly during the pandemic (spring 2020) than among respondents over 35 years old: 15% (from 46 to 61%) among 20- to 34-year-olds versus 5% (from 43 to 48%) among 35- to 44-year-olds (Makarentseva, 2020).

As for balancing a career and parenthood, it is achieved by having few children and with the support of relatives, as well as the ability to hire a nanny (Zhuk, 2016).

Conclusion

Thus, according to the results of in-depth interviews, the majority of young families are oriented toward the traditional full family and having children. In many respects their reproductive attitudes depend on the role model of parents’ and close relatives’ families, in particular on the nature of their relationship, and on instilling family values in their children.

There are two behavioral patterns among representatives of young families with regard to the role of the officially registered marriage in having children. For some, marriage continues to be an important condition for creating a family and having children (the traditional “marriage – family – children” sequence), while for others the role of marriage itself is less important against the background of a desire to have a “big family and many children”. As a rule, this is a female model of child-centrism, which, however, does not deny the importance of the husband as the father of the children.

The results of the interviews confirmed the fact that financial well-being, mainly own housing, plays an important role in the realization of the reproductive intentions of young families. It is noteworthy that three positions are observed among young family informants regarding state sociodemographic policy measures and their impact on having children: the first group – not counting on state support and not recognizing its influence on having children, the second group – counting on state support but not recognizing its influence on the realization of reproductive intentions, the third group – counting on state support and recognizing its influence on childbearing. The first position turned out to be the most common, which indicates, on the one hand, the socio-economic self-sufficiency of modern young families, on the other hand, the need to find new tools to stimulate reproductive attitudes in this population category, in particular increasing the need for children. Nevertheless, almost all informants recognize the significant role of maternity capital in solving the housing problem, which indicates its importance and popularity among young families.

Young family respondents generally do not see a problem in combining career and parenthood, but in fact the problem exists and is mediated through the popularity of the opinion that one should first “get on the feet” professionally and only then have children. In addition, there are great hopes for the help of the older generations.

As for the COVID-19 pandemic, it did not have a significant reproductive impact on many young families, namely it did not change their plans for having children. However, some of the informants among young couples postponed having a child “until better days”. This in itself is a factor contributing to the decline in the birth rate and requires serious scientific reflection.

All the above mentioned indicates that the “young family” category is rather heterogeneous both in the nature of reproductive attitudes and in the factors determining them: the influence of the family of origin, matrimonial behavior and attitude to marriage, attitude to measures of state sociodemographic policy, as well as the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which should be taken into account in the state socio-demographic, youth and family policy.

Список литературы Reproductive attitudes of young families: driving forces and implementation conditions (on the basis of in-depth interviews)

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Behaviour. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Andreev E.M., Bondarskaya G.A. (2000). Can we use data on the expected number of children in population projections? Voprosy statistiki, 11, 56–62 (in Russian).

- Andreev E.M., Bondarskaya G.A., Khar’kova T. (1998). Falling birthrate in Russia: Hypotheses and facts. Voprosy statistiki, 10, 82–93 (in Russian).

- Antonov A.I., Zhavoronkov A.V., Malyavin S.I. (2005). Reproductive orientations of a rural family: A study of the degree of father-mother coincidence in 20 regions of Russia. In: Elizarov V.V., Arkhangel’skii V.N. (Eds.). Politika narodonaseleniya: nastoyashchee i budushchee. IV Valenteevskie chteniya: sb. Dokladov [Population Policy: Present and Future. IV Valenteev Readings: Collection of Papers]. Moscow: MAKS Press (in Russian).

- Arkhangel’skii V.N. (1987). Attitudes toward having children in the value orientation system of the urban family. In: Demograficheskie aspekty uskoreniya sotsial’no-ekonomicheskogo razvitiya [Demographic Aspects of the Acceleration of Socio-Economic Development]. Kyiv: IE AN USSR (in Russian).

- Arkhangel’skii V.N. (2006). Faktory rozhdaemosti [Fertility Factors]. Moscow: TEIS.

- Arkhangel’skii V.N., Dzhanaeva N.G. (2014). Regional characteristic of fertility dynamics and demographic policy. Uroven’ zhizni naseleniya regionov Rossii=Living Standards of the Population in the Regions of Russia, 1(191), 73–82 (in Russian).

- Arkhangel’skii V.N., Elizarov V.V., Zvereva N.V., Ivanova L.Yu. (2005). Demograficheskoe povedenie i ego determinatsiya [Demographic Behavior and Its Determination]. Moscow: TEIS.

- Arkhangel’skii V.N., Rostovskaya T.K., Vasil’eva E.N. (2021). Influence of the standard of living on the reproductive behavior of Russians: Gender aspect. Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve=Woman in Russian Society, 3–24. DOI: 10.21064/WinRS.2021.0.1 (in Russian).

- Belova V.A. (1975). Chislo detei v sem’e [Number of Children in the Family]. Moscow: Statistika.

- Belova V.A., Darskii L.E. (1972). Statistika mnenii v izuchenii rozhdaemosti [Opinion Statistics in the Study of Fertility]. Moscow: Statistika.

- Bongaarts J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. Population and Development Review, 27, 260–281.

- Borisov V.A. (1976). Perspektivy rozhdaemosti [Prospects for Fertility]. Moscow: Statistika.

- Borozdina E., Zdravomyslova E., Temkina A. (2012). Maternity capital: Social policies and strategies for families. Demoskop Weekly=Demoscope Weekly, 495–496. Available at: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2012/0495/analit03.php (in Russian).

- Chernova Zh.V. (2010). “Demographic reserve”: A young family as an object of state policy. Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve=Woman in Russian Society, 2(55), 26–38 (in Russian).

- Coombs L.C. (1979). Reproductive goals and achieved fertility: A fifteen-year perspective. Demography, 16(4), 523–534.

- Darskii L.E. (1972). Statistika mnenii v izuchenii rozhdaemosti [Opinion Statistics in the Study of Fertility]. Moscow: Statistika.

- Darskii L.E. (1979). Fertility and family reproduction. In: Volkova A.G. (Ed.). Demograficheskoe razvitie sem’i [Demographic Development of the Family]. Moscow: Statistika (in Russian).

- Dement’eva I.F. (1991). Pervye gody braka: problemy stanovleniya molodoi sem’i [The First Years of Marriage: The Challenges of Becoming a Young Family]. Moscow: Nauka.

- Denisov S.B. (2000). The problem of defining the concept of “young family” in the theory and practice of social work. Vestnik Mordovskogo un-ta=Mordovia University Bulletin, 3, 47–53 (in Russian).

- Dobrovol’skaya V.M. (1974). Housing conditions and demographic behavior. In: Sem’ya i zhilaya yacheika: sb. nauch. trudov [The Family and the Living Unit: Collection of Scientific Works]. Moscow (in Russian).

- Golod S.I. (1998). Sem’ya i brak: istoriko-sotsiologicheskii analiz [Family and Marriage: A Historical and Sociological Analysis]. Saint Petersburg: Petropolis.

- Grishina O.V. (2008). Reproductive behavior of parents and their children in Russia. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya 6. Ekonomika=Moscow University Economics Bulletin, 6, 29–41 (in Russian).

- Gudkova T.B. (2019). Fertility intentions in Russia: Motivation and constraints. Demograficheskoe obozrenie=Demographic Review, 6(4), 83–103. DOI: 10.17323/demreview.v6i4.10428 (in Russian).

- Gurko T.A. (1985). Young family in a big city. In: Molodozheny: sb. statei [Newlyweds: Collection of Articles]. Moscow: Mysl’ (in Russian).

- Heiland F., Prskawetz A., Sanderson W.C. (2008). Are individuals’ desired family sizes stable? Evidence from West German panel data. European Journal of Population, 24(2), 129–156.

- Ipatova A.A., Tyndik A.O. (2015). Reproductive age: 30 years old in preferences and biographies. Mir Rossii. Sotsiologiya. Etnologiya=Universe of Russia. Sociology. Ethnology, 24(4), 123–148 (in Russian).

- Katkova I.P. (1971). Rozhdaemost’ v molodykh sem’yakh [Fertility in Young Families]. Moscow: Meditsina.

- Katkova I.P. (1973). Some socio-hygienic features of birth control in young families. In: Kompleksnoe izuchenie sostoyaniya zdorov’ya naseleniya Tambovskoi oblasti v svyazi s Vsesoyuznoi perepis’yu naseleniya 1970 [Comprehensive Study of the Population Health in the Tambov Oblast Related to the Soviet Census of 1970]. Tambov (in Russian).

- Kharchev A.G. (1979). Brak i sem’ya v SSSR [Marriage and Family in the USSR]. 2nd ed. revised and supplemented. Moscow: Mysl’.

- Krasnenkov V.L., Frolova N.A. (1984). Socio-hygienic aspects of birth control in young families living in rural areas. Sem’ya i obshchestvo=Family and Society, 24–25, Moscow.

- Kravtsova G.F., Pleshakova M.V. (1991). Formirovanie sem’i v dal’nevostochnom gorode [Family Formation in a Far Eastern City]. Khabarovsk: DVO AN SSSR.

- Kuz’menko T.V. (2010). Reproductive counsels of young married couple: impact of elder generation. Vestnik Nizhegorodskogo universiteta im. N.I. Lobachevskogo. Seriya: Sotsial’nye nauki=Vestnik of Lobachevsky State University of Nizhni Novgorod. Series: Social Sciences, 4(20), 60–67 (in Russian).

- Kuz’min A.I. (1986a). The influence of the relationship with parents on the demographic behavior of a young family. In: Razvitie i stabilizatsiya molodoi sem’I [Development and Stabilization of the Young Family]. Sverdlovsk (in Russian).

- Kuz’min A.I. (1986b). Regional features of fertility. In: Osobennosti vosproizvodstva i migratsii naseleniya na Urale: sb. nauch. tr. [Features of Reproduction and Migration in the Urals: Collection of Scientific Works]. Sverdlovsk: UNTs AN SSSR (in Russian).

- Kuz’min A.I. (1990). The role of the young family in the reproduction of the region’s population. In: Molodaya sem’ya i realizatsiya aktivnoi sotsial’noi politiki v regione: sb. nauch. tr. [The Young Family and the Implementation of Active Social Policy in the Region: Collection of Scientific Works]. Sverdlovsk (in Russian).

- Kuz’min A.I. (1993). Sem’ya na Urale: demogr. aspekty vybora zhizn. puti [Family in the Urals: Demographic Aspects of Life Choice]. Yekaterinburg: Nauka: Ural. izd. firma.

- Makarentseva A.O. (2020). The impact of the epidemiological situation on the reproductive intentions of the population. Monitoring ekonomicheskoi situatsii v Rossii. Tendentsii i vyzovy sotsial’no-ekonomicheskogo razvitiya= Monitoring of the economic situation in Russia. Trends and challenges of socio-economic development, 17(119). Available at: https://www.iep.ru/upload/iblock/2f2/3.pdf (accessed: February 15, 2022).

- Maleva T., Makarentseva A., Tret’yakova E. (2017). Pronatalist demographic policy in the eyes of the population: Ten years later. Ekonomicheskaya politika=Economic Policy, 12(6), 124–147 (in Russian).

- Matskovskii M.S., Gurko T.A. (1986a). Molodaya sem’ya v bol’shom gorode [Young Family in a Big City]. Moscow: Znanie.

- Matskovskii M.S., Gurko T.A. (1986b). Successful functioning of a young family in a large city. In: Matskovskii M.S. (Ed.). Programma sotsiologicheskikh issledovanii molodoi sem’i (programmy i metodiki issledovanii braka i sem’i) [Program of Sociological Research on Young Families (Marriage and Family Research Programs and Methods)]. Moscow (in Russian).

- Medkov V.M. (1986). Socio-demographic characteristics of spouses and their attitudes toward having children. In: Rybakovskii L.L. et al. (Eds.). Detnost’ sem’i: vchera, segodnya, zavtra [Children in the Family: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow.]. Moscow: Mysl’ (in Russian).

- Mitrofanova E.S. (2011). Marriages, partnerships and fertility of generations in Russia. Demoskop Weekly=Demoscope Weekly, 477–478. Available at: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2011/0477/tema01.php (accessed: February 15, 2022; in Russian).

- Mokerov I.P., Kuz’min A.I. (1990). Ekonomiko-demograficheskoe razvitie sem’I [Economic and Demographic Development of the Family]. Moscow: Nauka.

- Morgan S.P. (2001). Should fertility intentions inform fertility forecasts. In: Proceedings of U.S. Census Bureau Conference: The Direction of Fertility in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

- Morgan S.P., Rackin H. (2010). The correspondence between fertility intentions and behavior in the United States. Population and Development Review, 36(1), 91–118.

- Osipova I. (2020). Reproductive attitudes of Russians and how they regard government measures to support fertility. Demograficheskoe obozrenie=Demographic Review, 7(2), 97–120. DOI: 10.17323/demreview.v7i2.11143 (in Russian).

- Philipov D. (2009). Fertility intentions and outcomes: The role of policies to close the gap. European Journal of Population, 25(4), article number 355. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9202-1

- Rodzinskaya I.Yu. (1986). Factors affecting the reproductive attitudes of spouses. In: Detnost’ sem’i: vchera, segodnya, zavtra [Children in the Family: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow.]. Moscow: Mysl’ (in Russian).

- Rostovskaya T.K. (2014). The status of a young family in the modern Russian society. Chelovek v mire kul’tury=Man in the World of Culture, 3, 74–80 (in Russian).

- Rostovskaya T.K., Arkhangel’skii V.N., Ivanova A.E., et al. (2021а). Sem’ya i demograficheskie protsessy v sovremennoi Rossii: monografiya [Family and Demographic Processes in Modern Russia: Monograph]. FNISTs RAN. Moscow: Ekon-Inform.

- Rostovskaya T.K., Shabunova A.A. et al. (2021c). Demograficheskoe samochuvstvie regionov Rossii. Natsional’nyi demograficheskii doklad-2021 [Demographic well-being of Russian regions. National Demographic Report-2021]. Moscow: FNISTs RAN.

- Rostovskaya T.K., Shabunova A.A., Arkhangel’skii V.N. et al. (2021d). Demograficheskoe samochuvstvie regionov Rossii. Natsional’nyi demograficheskii doklad-2020 [Demographic well-being of Russian regions. National Demographic Report-2020]. FNISTs RAN. Moscow: Perspektiva.

- Rostovskaya T.K., Vasil’eva E.N., Knyaz’kova E.A. (2021b). Tools for in-depth interview to analyze inner motivation of reproductive, matrimonial, self-preserving and migration behavior. Voprosy upravleniya=Management Issues, 1(68), 103–117. DOI: 10.22394/2304-3369-2021-1-103-117 (in Russian).

- Rusanova N.E. (2020). Post-pandemic birth rate: “Baby boom” or “demographic hole”? Vestnik Moskovskogo finansovo-yuridicheskogo universiteta=Herald of the Moscow University of Finances and Law MFUA, 4, 152–159 (in Russian).

- Safonova T.E. (1982). Number of children in the family of origin and reproductive orientations. In: Sem’ya i deti: tezisy dokladov vsesoyuznoi konferentsii [Family and Children: Abstracts of Reports of the All-Union Conference] (in Russian).

- Shabunova A.A., Kalachikova O.N. (2008). Reproductive choice of modern family. Problemy razvitiya territorii=Problems of Territory’s Development, 41, 62–67 (in Russian).

- Shabunova A.A., Kalachikova O.N. (2013). On the reasons for the growth of the birth rate in the period of activation of Russia’s demographic policy (in the case of the Vologda Oblast). Problemy prognozirovaniya=Studies on Russian Economic Development, 5(140), 129–136 (in Russian).

- Shabunova A.A., Kalachikova O.N., Korolenko A.V. (2021). Demograficheskaya situatsiya i sotsial’no-demograficheskaya politika Vologodskoi oblasti v usloviyakh pandemii COVID-19: II regional’nyi demograficheskii doklad [Demographic Situation and Socio-Demographic Policy of the Vologda Oblast in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: II Regional Demographic Report]. Vologda: VolNTs RAN.

- Sinel’nikov A.B. (1989). Brachnost’ i rozhdaemost’ v SSSR [Marriage and Fertility Rate in the USSR]. Moscow: Nauka.

- Testa M.R., Sobotka T., Morgan P.S. (2011). Reproductive decision-making: Towards improved theoretical, methodological and empirical approaches. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 9, 1–9.

- Tyndik A.O. (2012). Reproductive attitudes and their realization in modern Russia. Zhurnal issledovanii sotsial’noi politiki=The Journal of Social Policy Studies, 10(3), 361–376 (in Russian).

- Van de Kaa D.J. (2001). Postmodern fertility preferences: From changing value orientation to new behavior. Population and Development Review, 27, 290–331.

- Van Peer C., Rabušic L. (2008). Will we witness an upturn in European fertility in the near future? In: People, Population Change and Policies. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Varlamova S.N., Noskova A.V., Sedova N.N. (2006). Family and children in the attitudes of Russians. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 10, 61–73 (in Russian).

- Volkov A.G. (1986). Sem’ya – ob’’ekt demografii [Family as an Object of Demography]. Moscow: Mysl’.

- Westoff C.F. (1990). Reproductive intentions and fertility rates. International Family Planning Perspectives, 16(3), 84–96.

- Zhuk E.I. (2016). Reproductive settings of young and middle-aged muscovites. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny=Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes Journal, 1, 156–174. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2016.1.06 (in Russian).

- Zotin V., Mytil’ A. (1987). Ideas of newlyweds about the number of children in the family. In: Valentei D.I. et al. (Eds.). Gorodskaya i sel’skaya sem’ya [Urban and Rural Families]. Moscow: Mysl’ (in Russian).

- Zuikova E.M., Kuznetsova N.V. (1994). Molodaya sem’ya [Young Family]. Moscow: Soyuz.