Social capital in a region: revisiting the measurement and building of an indicator model

Автор: Afanasev Dmitrii Vladimirovich, Guzhavina Tatyana Anatolevna, Mekhova Albina Anatolevna

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 6 (48) т.9, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The concept of social capital is gaining certain stability in the social studies. The heuristic potential of the concept is confirmed by numerous studies which prove the positive impact of levels and types of social capital on a wide range of social phenomena. Approaches to theoretical justification of social capital empirical appraisal are being formed, which is particularly relevant amid of general economic and structural crisis. However, science still lacks a generally accepted definition of social capital and the agreement on the ways to measure it. The article aims to theoretically justify the building of an indicator model for empirical measurement of social capital, which implies a set of indicators generated for a particular conceptual framework and helping obtain organized information about the phenomenon under study in order to identify the correlation between its components. The article is intended to foreground the need for social capital empirical measurement and comparison...

Social capital, social capital components, levels of social capital, measurement indicators, indicator model of social capital measurement, index method

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223882

IDR: 147223882 | УДК: 316.4 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2016.6.48.6

Текст научной статьи Social capital in a region: revisiting the measurement and building of an indicator model

The concept of social capital is acquiring a stable nature. Social capital is recognized as a necessary connection which unites other types of fixed capital – natural, physical and human. Fixed capital forms the country’s wealth and the basis for economic growth and development. The composition and share of specific types of capital in its structure constantly change.

Natural capital is depleted over time and converted into physical, which, in its turn, is also depreciated over time. Human capital is associated with a particular individual and becomes important only when the individual is included in social relations and interaction. Nowadays the importance of relations arising in connection with how organized is the process of interaction of individuals and society as a whole for achieving certain results has become obvious. They are the “social glue” known as “social capital”. Despite this thesis being obvious, in science there is no consensus about which aspects of interaction and organization should be considered as social capital. The issue of measurement of social capital still remains complex and understudied. The search for ways to empirically determinate its contribution to economic growth and development also requires attention [1].

Social capital is a development resource affecting economic growth, social welfare, efficiency of social programs, etc. It primarily depends on the quality of public services such as education and health. Social capital also affects health, reproductive potential, public safety, quality of public services and public administration. This raises the question: how, using what means is it possible to create conditions for social capital accumulation?

Although the issue of social capital has been in the center of attention of economists, political scientists, psychologists, sociologists for almost two decades, having different points of view, approaches and expectations, which leads to its wider interpretation. And this, in its turn, results in the possibility of erosion of an already vague specificity of the concept including complete loss of its heuristic potential, its transformation into a journalistic clich . With a sufficient number of publications devoted to social capital, most of them are based on a similar strategy – citations of works of key authors in this field who had made a significant contribution to the interpretation and definition of social capital, creating an opportunity of this subject’s interpretation. Among them are: Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, Robert Putnam, Francis Fukuyama and others. Nowadays, there is an unquestionable point of view stating that social capital is a complex concept which covers several dimensions: sociological (presented primarily by J. Coleman), economic (P. Bourdieu, F. Fukuyama) and political (R. Putnam).

When tracking the theoretical lines in the most famous explanatory diagrams, it becomes obvious that the concept of social capital is represented, first of all, as a fundamental expansion and development of the issue of economic relations in the Marx’s theory of capital; second, as an extension and development of integration or Durkheim’s view of social relations; third, as a continuation and development of the approach to understanding the functioning of democracy in political science dating back to the treatises of Alexis de Tocqueville. In this context, the idea of the triadic nature of the concept expressed by the authors and editors of the book “Handbook of Social Capital: The Troika of Sociology, Political Science and Economics” seems very productive [21]. This is one of the most representative attempts of a meaningful conceptualization and empirical description of social capital in recent years.

Analysis of the established approaches to the interpretation of social capital makes it possible to believe that social capital is a multi-aspect phenomenon, hence the interest from economics, political science, sociology, psychology, and cultural studies. Despite some differences in approaches, they all see the essence of social capital in the developing relations, in the fact that only they are of particular value. These relations form the social context which can give individuals and groups access to various resources. All the key authors share the viewpoint according to which social capital is composed of resources embedded in social relations and social structure which can be mobilized when an actor is willing to improve the likelihood of the success of certain purposeful actions.

The metaphor presenting social capital as a “lubricant” in the mechanism of social interactions has become popular. Thanks to the social capital cooperation between the parties becomes more successful. Individual mechanisms are involved in this process (e.g., personalized trust), which lead to lower transaction costs of the parties. At the group level, this mechanism is no longer personal, the individual’s belonging to the community is important. As for the macro-level, values and norms universal for the whole society become relevant here.

The concept of social capital, having emerged due to the comparative study of regions, has helped see the impact of this phenomenon on regional development. The first comparative analysis of regional differences was conducted by Putnam and Halliwell using the example of Italy; then S. Panebianco used their technique to study German regions [34; 35]. The difference in the patterns of social capital in the regions of West Germany and their influence on the pace and nature of economic growth was demonstrated by Blume and Sack [16]. Data analysis in rural areas of France war performed by Callois and Schmitt [17]. J. Dzialek [19] gave a description of the spatial structure of social capital in Poland. Based on European material (data of World Values

Survey), Knack and Keefer, La Porta conducted a comparative study of the effect of trust on the countries’ growth rates, showing their relations [22; 25]. Thus, research materials regarding the specifics of performance of social capital in a regional context have been gradually accumulated.

The first attempts to apply the concept of social capital to explore Russian regions were undertaken in the study of C. Marsh [27; 28; 29] who proposed an original methodology of measuring the index of social capital. He discovered a correlation between the civil society index and the index of democratization. J. Twigg and K. Schecter offered their scale of comparative measurement of social capital of various Russian regions [37]. For their study they used statistical data. However, due to the specificity of the selected indicators both methods could not be comparable with other studies.

Among very few domestic studies of social capital the authors note the research of L.I. Polishchuk and R.I. Nenashev, as well as the work of E. Trubekhina. E. Tru-bekhina, on the basis of the methodology of Beugelsdijk and Smulders, analyzed data of the study “Georating” conducted by the Public Opinion Foundation, supplementing it with statistics, and identified a strong connection between the degree of participation in various groups and organizations (open social capital) with the per capita GRP [14].

L.I. Polishchuk and R.I. Menyashev established a significant positive relation between the efficiency of local administrations and the open social capital and civil culture. According to them, Russia has a significant social capital stock which is very unevenly distributed between the country’s cities and regions [10]. According to the results of their study, one of the leaders in the Vologda Oblast is Cherepovets – a large industrial centre in the NorthWest of Russia. The city demonstrated the highest levels of open social capital, a well-developed civil culture and less pronounced closed networks. The researchers believe that social capital stock is high in the Northwestern ports – Murmansk and Arkhangelsk, its level is relatively high in Tomsk and in a number of other cities. Cities such as Krasnodar, Saratov and Magnitogorsk are at the bottom of the ranking; Moscow is in the middle. It should be noted that the researchers stated that their data require clarification and confirmation from other sources [30]. L.I. Polishchuk claims in his conclusions that social capital is an exclusively “local” product and sets an objective arising from the importance of social capital for regional development: “It is necessary to create favorable conditions for its reproduction and accumulation supporting the educational system (including at public expense), opening opportunities for public initiatives and self-organization in business and everyday life” [30]. The authors agree with the position of L.I. Polishchuk in terms of the relevance of regional aspects of social capital. Bearers of social capital are connected with a particular territory – by place of residence or study, work or business. Here, different communities of individual, families and friends, professional, and cultural etc. members are formed. This suggests the presence of social capital of a territorial (regional) community.

The difficulty in the interpretation of social capital, reflecting its multi-aspect nature, creates the methodological difficulties of its measurement and evaluation. The problem is that at the moment there are no well-established methods, the methodology is imperfect and data quality is compromised. There is lack of general understanding of how, by what criteria, using what indicators social capital is to be measured. Attempts to measure it often lead to the blending of its sources and results. A major part of what constitutes social capital exists in an vague or relative form and deprives researchers of the ability of a simple measurement or codification.

The solution to the problem of measuring social capital depends largely on the chosen theoretical model. Comparative characteristics of the applied indicators ( Tab. 1 ) makes it possible to observe both common indicators and some differences generated by the peculiarities of the authors’ theoretical positions.

According to O. Demkiv, it is necessary to separate primary and secondary operational parameters which measure social capital. He considers components as primary parameters (networks, values, norms, trust), and consequences as secondary (level of deviant behavior, informal social control, social integratedness, level of social support, etc.) [5].

-

V. Nilov distinguishes “proximal” and “distal” indicators of social capital. The former consist of practical results of the influence of social capital on various aspects of people’s lives and are associated with its main components – networks, trust and mutuality in relationship. The latter are presented as the result of this influence, not directly associated with its key components such as health, crime level, life expectancy etc. [8]. This is

Table 1. Comparative characteristics of indicator models depending on the conceptual model*

A.N. Tatarko uses trust, civil identity, social amity, ethnic tolerance as indicators for measuring social capital [13].

L.I. Polischuk relies on the following indicators: social amity, solidarity; readiness for collective actions; trust; responsibility for a family; responsibility for the situation in the city [9].

Summary analysis of the practical study of social capital in mass surveys conducted by I.N. Vorobyeva and A.A. Mekhova helped them not only to describe the structure of social capital, but also to fill it with indicators, including communication aspects. These include: participation in social organizations, groups; trust; solidarity and willingness to unite, information and communication [2; 7].

Experts of ISEDT RAS use indicators such as trust, responsibility for the situation, amity, readiness to unite, inclusion, ability to influence to assess social capital [3; 4; 15].

The applied sets of indicators have common elements, however their values are not completely coincident, therefore it seems problematic to come to a unified and complete measurement of social capital. A wide variety of elements included by various authors in the interpretation of social capital makes it difficult to compare the results of different measurements.

The World Bank which in 1996–2000 implemented a large-scale project “Initiative on defining, monitoring and measuring social capital” (SCI), developed a methodology to measure social capital in the framework of this project –(Social Capital Assessment Tool (SOCAT) and an Social Capital Integrated Questionnaire (SOCAP IQ). The SOCAP IQ was designed to: (1) take an inventory of the levels of social capital in the society; (2) reveal how social capital is distributed among socioeconomic groups and (3) measure the community’s capacity to participate in mutually beneficial collective goals.

The representatives of SCI define social capital as institutions, norms, values and beliefs which regulate people’s interaction and contribute to economic and social development. It consists of several social and cultural phenomena, including values which predispose people to cooperate. The first and foremost phenomenon is trust and mutuality, as well as institutional forms which promote cooperation such as local organizations, associations and rules governing them. According to SCI, these indicators taken together may be measured to assess the communities’ capacity to be organized for mutually beneficial purposes [24].

The World Bank’s approach to the measurement of social capital is fully supported by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [33].

Another approach of a pragmatic nature is associated with the use of available materials of World and European Value Survey. The majority of foreign studies including European are, as a rule, secondary. Databases collected during the World Value Survey (World Values Survey) [39] and European Social Survey [20] are at the disposal of researchers. Of course, data were collected not studying social capital but for other purposes, so they do not fully provide conceptually strict indicators of social capital [11].

A.A. Stebakov identified three main methods of measuring social capital: the method based on trust radius, the indexrating method, the World Bank method (SOCAT), noting that the disadvantage of the method based on the trust radius calculation lies in the need for extensive research, as well as in rapid data deterioration [12].

It is necessary to note a number of attempts to integrate various approaches in a single measurement technique. This results in the proliferation of index methods of measuring social capital. The index method implies the use of readymade indicators. The measurement of social capita; is based of the use of indices such as index of trust, index of corruption and country prosperity index, etc. On the one hand, this approach helps evaluate social capital as a multiaspect phenomenon, and take into account its various characteristics; on the other hand, the use of diverse sets of indicators by researchers does not always give an opportunity to make the results comparable.

It is obvious that empirical measurement requires a clearer definition of social capital. Based on the analysis of different approaches and definitions of social capital, the authors introduce their own interpretation of the term. In their opinion, the most successful and productive is the approach formulated by Steven Derlauf and Marseille Fafchamps in their work “Social Capital”. They distinguish three main ideas which can be traced in almost all existing definitions. “First, social capital generates (positive) external effects for group members. Second, these external effects are achieved through joint trust, norms and values and their consequent impact on the expectations and behavior. Third, general trust, norms and values arise from informal organizations based on social networks and associations” [18, p. 1644]. Thus, social capital implies, first, the existence of networks of social relations characterized by trust and mutuality norms, the degree of people’s participation in them, and, ultimately, the external effects useful for the and social groups (in the specified article’s context – for a region) and the results generated by social interaction within interpersonal networks and associations based on trust, common norms and values.

The ambiguous interpretation of the structure of social capital also hampers the formation of the indicator measurement model. Summing up the positions concerning the elements of social capital, which serve as the starting points for constructing a system of indicators, the group of authors uses the term “social capital” believing that these forms are structural and cognitive capital [6]. The authors refer to the work of J. Nahapiet and S. Ghoshal; however that work does not cover the types or forms of social capital, but its dimensions (aspects). J. Nahapiet and S. Ghoshal distinguish three aspects of social capital: structural, relational and cognitive, emphasizing the strong correlation between the three aspects [30].

In the authors’ opinion, the structural and cognitive (or rather, culture-based) aspects are not different forms of social capital, but two dimensions or aspects of social capital distinguished analytically: the structural aspect and the aspect of attitudes. The structural aspect shows how people are attached to different groups and organizations (networks), while the culture-based (cognitive and attitudebased) aspect is based on people’s trust in the others, their readiness to unite with other people and the ability to influence the situation and the course of events. Network structures can be related to both formal and informal, including virtual ones, so when analyzing social capital, it is necessary to consider both these components.

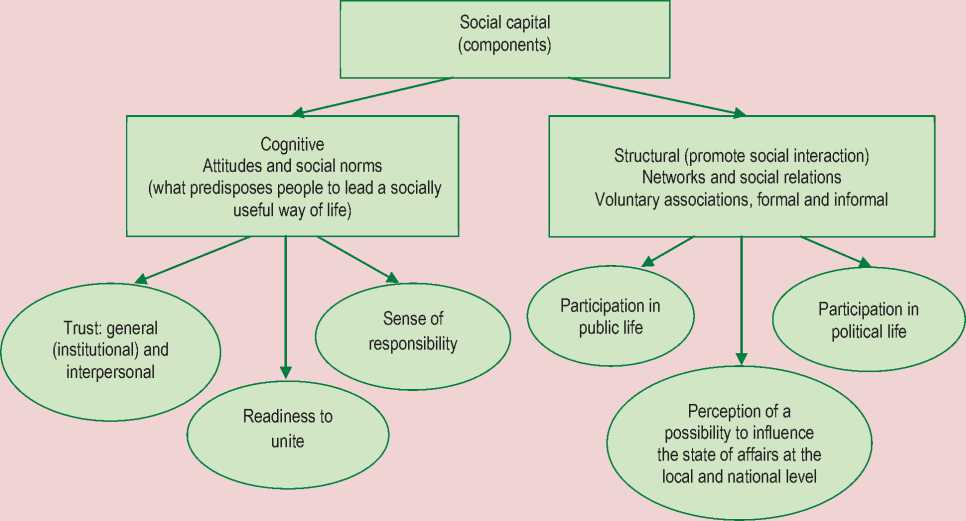

The authors believe that, due to the fundamental importance of distinguishing bridging and bonding capital (because of their different degree of significance for economic growth), it is necessary to identify specific indicators of these types and their formal and informal components. Thus, they logically distinguish the following structure of components and indicators of social capital ( Figure ).

Components of social capital and their indicators

The levels of performance of social capital also need to be taken into account, moreover, intermediate, or meso-level may also need to be distinguished ( Tab. 2 ).

The measurement of bridging and bonding social capital represents a separate problem. Operationalization of distinction between binding, bridging and (optionally) linking types of social capital is difficult because there are multiple and intertwined relations of individuals with each other. The distinction between types of social capital may require an additional broad series of questions depending on the studied aspect.

Based on the above-formulated principles of building an indicator model, the authors define it as a set of indicators generated on a particular conceptual base and helping obtain organized information about the studied phenomenon or process, identify the correlation between the constituent elements.

The structure of the social capital indicator model may include groups of indicators measuring both cognitive and structural component of social capital ( Tab. 3 ). The evaluation uses the index method, which helps, on the basis of the obtained values, perform comparative

Table 2. Social capital performance levels

|

Macro-level |

Meso-level |

Micro-level |

|

|

Structural |

Formal political participation, following rules and laws |

Participation in interest groups (trade unions, political parties, corporate associations) |

Voluntary networks including virtual, families, friends and acquaintances Effectiveness (perception of an ability to influence the state of affairs) |

|

Cognitive (culture-based) |

Institutional trust Sense of responsibility |

Readiness to unite and act together (group solidarity) |

Interpersonal trust |

Table 3. Indicator model of social capital measurement*

Since the number of the used indicators will be quite significant and some of them will correlate with each other, it is necessary to systematize this analysis using the principal components method and transform many correlated variables into several non-correlated ones. This will help, on the one hand, identify the factors behind these data, to validate theoretical considerations, on the other hand, explore data and discover new relations between them. As a result, a set generalized and systematic components and dimensions of social capital of the region may be obtained, structured by both institutional form (formal – informal) and location.

Список литературы Social capital in a region: revisiting the measurement and building of an indicator model

- Afanas'ev D.V. K issledovaniyu roli sotsial'nogo kapitala regionov v usloviyakh sotsial'no-ekonomicheskogo krizisa . Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz , 2015, no. 4, pp. 88-108.

- Guzhavina T.A. (Ed.), Vorob'eva I.N., Mekhova A.A. Teoretiko-metodologicheskie problemy izmereniya sotsial'nogo kapitala . Sotsial'nyi kapital kak resurs modernizatsii v regione: problemy formirovaniya i izmereniya: materialy Mezhregional'noi nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii (g. Cherepovets, 16-17 oktyabrya 2012 g): v 2 ch . Cherepovets: ChGU, 2012. Part 1, pp. 103-109.

- Guzhavina T.A. Sotsial'nyi kapital regiona kak faktor modernizatsii . Problemy razvitiya territorii , 2016, no. 1, pp. 130-144.

- Guzhavina T.A. Doverie v kontekste neekonomicheskikh faktorov modernizatsionnogo razvitiya . Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz , 2014, no. 4, pp. 190-194.

- Demkiv O. Sotsial'nyi kapital: teoreticheskie osnovaniya issledovaniya i operatsionnye parametry. . Sotsiologiya: teoriya, metody, marketing , 2004, no. 4, pp. 99-111.

- Macheriskene I., Minkute-Henriksson R., Simanavichene Zh. Sotsial'nyi kapital organizatsii: metodologiya issledovaniya . Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya , 2006, no. 3, pp. 31-32.

- Kozlova O.V., Novikov A.E., Alekseeva N.V. (Eds.), Mekhova A.A. Sotsial'nyi kapital v kontekste problem sotsial'noi spravedlivosti . Problemy sotsial'noi spravedlivosti i sovremennyi mir: materialy VI Vserossiiskoi (s mezhdunarodnym uchastiem) nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii (g. Cherepovets, 24-26 marta 2016 g.) . Cherepovets: ChGU, 2016. Pp. 44-49.

- Nilov V. Metody izmereniya sotsial'nogo kapitala i ikh ispol'zovanie v nauchnykh issledovaniyakh . Sotsial'naya innovatika v regional'nom razvitii: sbornik materialov V shkoly molodykh uchenykh . Petrozavodsk: Karel'skii nauchnyi tsentr RAN, 2009. Pp. 141-149.

- Polishchuk L. Sotsial'nyi kapital v Rossii: izmerenie, analiz, otsenka vliyaniya . Available at: http://www.liberal.ru/articles/5265.

- Polishchuk L., Menyashev R.Sh. Ekonomicheskoe znachenie sotsial'nogo kapitala . Voprosy ekonomiki , 2011, no. 12, pp. 46-65.

- Adam F., Podmenik D. Sotsial'nyi kapital v evropeiskikh issledovaniyakh . Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya , 2010, no. 11, pp. 35-48.

- Stebakov A.A. Metody izmereniya urovnya sotsial'nogo kapitala v Rossii i za rubezhom . Izv. Sarat. un-ta. Ser: Ekonomika. Upravlenie. Pravo , 2014, volume 14, issue 2, part 2, pp. 430-436.

- Tatarko A.N. Sotsial'nyi kapital sovremennoi Rossii: psikhologicheskii analiz . Vestnik MGGU im. M.A. Sholokhova. Pedagogika i psikhologiya , 2012, no.3, pp. 68-82.

- Trubekhina I.E. Sotsial'nyi kapital i ekonomicheskoe razvitie v regionakh Rossii . INEM-2012. Trudy II Vserossiiskoi (s mezhdunarodnym uchastiem) nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii v sfere innovatsii, ekonomiki i menedzhmenta, g. Tomsk, 24 apr. 2012 g . Tomsk: Izd-vo Tomskogo politekh. un-ta, 2012. Pp. 357-361.

- Shabunova A.A., Guzhavina T.A., Kozhina T.P. Doverie i obshchestvennoe razvitie v Rossii . Problemy razvitiya territorii , 2015, no. 2, pp. 7-19.

- Blume L., Sack D. Patterns of social capital in West German regions. European Urban and Regional Studies, 2008, no. 15, pp. 229-248.

- Callois J.M, Schmitt B. The role of social capital components on local economic growth: Local cohesion and openness in French rural areas. Review of Agricultural and Environmental Studies, 2009, no. 90 (3), pp. 257-286.

- Durlauf S.N., Fafchamps M., Aghion P., Durlauf S. (Ed.). Social Capital. Handbook of Economic Growth, Elsevier, 2005, volume 1b, pp. 1639-1699.

- Dzialek J. Is social capital useful for explaining economic development in polish regions? Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 2014, volume 96, no. 2, pp. 177-193.

- Eropien Sosial Survey (ESS). Available at:www.europeansocialsurvey.org

- Svensen G.T., Svenddsen G.L.H. (Eds.). Handbook of Social Capital: The Troika of Sociology, Political Science and Economics. Northampton, MA; Edvard Elgar, 2009.

- Knack S., Keefer P. Does social capital have an economic pay-off? A cross country investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1997, no. 112.4, pp.1251-1288.

- Kreuter M.W., Young L.A., Lezin N.A. Measuring Social Capital in Small Communities. Study conducted by Health 2000 Inc., Atlanta GA in cooperation with St. Louis School of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia. 1999.

- Krishna A., Shrader S., Bastelar van T.C. (Ed.). The social capital assessment tool: Design and Implementation. Understanding and Measuring Social Capital. Washington DC: The World Bank. 2002.

- La Porta R., Lopez-de-Silanes F., Schleifer A., Vishny R.W. Trust in Large Organizations. American Economic Review, 1997, volume 87, pp. 333-338.

- Lochner K., Kawachi I., Kennedy B.P. Social capital: a guide to its measurement. Health& Place,1999, no. 5 (4), pp. 259-270;

- Marsh C. Making Russian Democracy Work. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2000.

- Marsh C. Social Capital and Democracy in Russia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 2000, no. 33, pp. 183-199.

- Marsh C. Social Capital and Grassroots Democracy in Russia's Regions: Evidence from the 1999-2001 Gubernatorial Elections. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratisation, 2002, volume 10, no. 1, pp. 19-36.

- Menyashev R., Polishchuk L. Does Social Capital Have Economic Payoff in Russia?: working paper WP10/2011/01. Higher School of Economics. Moscow: Publishing House of the Higher School of Economics, 2011. 44 p.

- Nahapiet J., Ghoshal S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Academy of Management Review, 1998, volume 23, pp. 242-266.

- Narayan D., Cassidy M. F. A Dimensional Approach to Measuring Social Capital: Development and Validation of a Social Capital Inventory. Current Sociology, 2001, no. 49 (2), pp. 59-102;

- OECD The Well-being of Nations: The Role of Human and Social Capital, Paris, 2001.

- Panebianco S., The impact of social capital on regional economic development. ACSP Congress, Lovanio, 2003.

- Putnam R, Helliwell J. Economic Growth and Social Capital in Italy. Eastern. Economic Journal, 1995, no. 21(3), pp. 295-307.

- Stone W. Measuring social Capital. Towards a theoretically informed measurement framework for researching social capital in family and community life. Australian Institute of Family Studies. Research Paper, 2001, no. 24.

- Twigg J.L., Schecter K. Social Capital. Social Capital and Social Cohesion in Post-Soviet Russia. Armonk. M.E. Sharpe, 2003, pp. 168-188.

- Woolcock M. Measuring Social Capital. An Integrated Questionnaire. World Bank, Washington D.C., 2003.

- World Values Survey. Available at: www.worldvaluessurvey.org