Social innovation in Spain, China and Russia: key aspects of development

Автор: Soloveva Tatyana S., Popov Andrei V., Caro-Gonzalez Antonia, Hua Li, Соловьева Т.С.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Innovation development

Статья в выпуске: 2 (56) т.11, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

As traditional methods of governance are unable to promptly respond to the conglomerate of issues brought about by system-wide changes and modernity, social innovation is seen as a promising alternative. Its uptake, however, is facilitated and hindered by a variety of factors. Using Spain, China, and Russia as country cases, this article explicates the findings of a systems-based comparative analysis on the drivers and barriers to the development of social innovations as effective tools in addressing social problems. In depth research projects carried out at national or regional levels provides the background knowledge to analyze the scope, size, trajectory, goals and target groups of the initiatives, as well as the geographical, historical and socio-economic frameworks and environments of the social innovations studied. It was found that there is a need to further clarify the concept of social innovation and to stimulate awareness and public support for social entrepreneurship across all three cases. Specific fiscal, legislative, and social measures are also identified for social innovation initiatives to flourish in each of the three countries analyzed. These findings provide a valuable contribution to public policy by illuminating practical ways to move forward in making social innovation an effective and sustainable strategy for addressing pertinent societal issues.

Social innovation, social policy, drivers, barriers, social entrepreneurship, management, social development

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147224045

IDR: 147224045 | УДК: 338.22:364 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2018.2.56.4

Текст научной статьи Social innovation in Spain, China and Russia: key aspects of development

In the context of deeply-rooted, globalized, and system-wide societal challenges (unemployment, social inequality, poverty, etc.), the global community is searching for effective ways and methods to address the emerging new drivers of modernity (global migration, demographic change and ageing population, transformation of employment, etc.). Practice shows that traditional methods of government and market regulation cannot always respond in a timely fashion to ongoing changes; this leads to so-called “government failure” and “market failure”. In this regard, social innovation is considered and is increasingly used as an effective tool to address such downturns.

Generally, innovation is understood as something new that aims to solve social problems or mitigate their negative consequences. In this regard, it is noted that during crisis periods, social innovation has traditionally helped achieve sustainable growth, increase income, preserve jobs, and promote competitiveness [2].

Civil society, non-profit organizations and business entities have a critical role to play in the development and implementation of such initiatives. For instance, in the field of the “silver economy”1, one of the aims of which is to prolong the working lives of people in

Europe, related initiatives and programs have been implemented on the basis of publicprivate partnerships [1].

Unlike traditional technological innovation, social innovation has, in general, a wider scope of application and is difficult to assess, especially with quantitative means, as its effects are not manifested quickly and are not easily traceable with the issue of attribution2 of social impact. As a rule, the impact of social innovation on the socio-economic development of territories is complex; it usually manifests itself via the introduction of one innovation that leads to a number of interrelated transformations [3, p. 76], with processes emerging from collective creativity and/or collaborations.

Despite the growing demand from the state and society for social innovations, their development is hampered by many factors, which vary depending on the level of socioeconomic development of each country, its political structure, the availability of relevant legal framework, the state of civil society, etc. All these factors emphasize the relevance of this paper, which seeks to identify the drivers of and barriers to the development of social innovations as effective tools for addressing social problems in different regions of the world. For this study, regions in three countries – Spain, China and Russia – have been chosen as their geographic and civic features help reveal the specificities of the development of social innovation with three cases: a mature example from the Basque Country, a developed region in Spain as part of a Southern European country; a large Communist Asian country, China; and Russia, also a large country, that has assimilated some features of the other two types of society.

Conceptual framework and methodology

The origins of social innovation date back to the works of R. Owen, K. Marx, M. Weber, E. Durkheim [5, 6, 7, 8] and others. “Social innovation” began to be used as an economic term in the second half of the 20th century in the works of P. Drucker and M. Young [9, 10]. Later on, as the attention of the scientific and political community grew and focused on this subject, more concepts and theories of social innovation emerged. E. Pol and S. Ville, based on a review of the experiences to date, identified the following four areas:

– social innovation as a driving force of institutional change (R. Martin, S. Osberg, R. Scott, etc.);

– social innovation as a new idea aimed at achieving social goals and satisfying social needs (J. Mulgan, S. Tucker, B. Sanders, etc.);

– social innovation as an idea of public good (Center for Social Innovation, etc.), as a new solution to social problems aimed at improving the quality of life of the whole of society rather than individuals (J. Phills, K. Deiglmeier, D. Miller, etc.);

– social innovation as a new way to overcome social problems that are not susceptible to market influence (OECD, European Commission, etc.) [11].

Analysis of modern scientific literature suggests that two main directions have emerged in the development of social innovation concepts [12, pp. 66-69]: The functionalist approach, which regards social innovations as producers of social services demand for which cannot be met by the state and the market [13]; and the transformationalist approach, which defines social innovation as a process that initiates or promotes the institutionalization of new practices and rules for the purpose of the socio-political transformation of society [14; 15].

This paper takes a combined system approach and defines social innovations as new social practices in a particular sphere of life that are purposefully initiated by individual actors/ groups of actors in order to satisfy the needs of the population/address social issues; if institutionalized, these social practices can lead to system-wide social change. This interpretation enables us to consider the essence of this phenomenon more widely and to show its importance for the socio-economic development of territories.

A social innovation can be a new product (assistive technologies for people with disabilities), a service (mobile banking), a process (peer-to-peer collaboration and crowdsourcing), a market development (fair trade or time banking), a platform (legal or regulatory frameworks, ways of providing assistance), an organizational form (community interest companies), a business model (social franchising), or a combination of the above [4, p. 25].

A comparative analysis of three benchmark social innovation projects in three different countries (Spain, Russia, and China) is used to identify common and specific features, key drivers of, and barriers to the development of social innovation in certain regions of the world.

In order to understand processes of social innovation more profoundly, we use benchmarking for the most successful social innovation projects in the countries under consideration.

Heterogeneous responses to employment challenges: examining benchmark social innovation initiatives in Spain, China and Russia

Experience of Spain. A long tradition of social innovations in Spain3 (e.g. the Emaus movement in the Basque Country and Ecovillages in Catalonia) reflects bottom-up, collaborative and/or creative changes in response to societal challenges linked to specific contexts and moments in time (e.g. Catalonian and Basque social economy entrepreneurial initiatives). However, according to the Social Innovation Index 2016 published by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) [14], Spain ranks 28th, making it one of the lowest-performing countries in relation to its income level, along with Japan. Spain stands out as being consistently below average in all four dimensions analyzed (institutional policy framework, financing, entrepreneurship, and civil society). One explanation is that “social innovation” is a relatively recent and to date seldom-used term in Spanish public policy and programs and in the position papers of social entities and umbrella organizations. Furthermore, the term “social innovation” evokes different visions and understandings amongst stakeholders as it is a term with little consensus [5]. It is mostly understood as modernization4 or as an opportunity to give legitimacy to the third sector. Fernandez,

Pineda and Chaves consider social innovation in Spain as part of the so-called “social innovation model”, which responds to the different dimensions of the crisis in the welfare state [15]. These authors present social innovation as a solution to the crisis in Spain, heading towards the development of a new socio-economic paradigm.

With the onset of the economic crisis in 2008, Spain began to experience dramatic changes in unemployment, budget cuts, and social services. By 2015 Spain, Greece, and Croatia were showing the slowest recoveries and the heaviest losses in the EU from the 2008 socio-economic crash. Unemployment in Spain peaked in the first quarter of 2013 at more than 25%. Levels have since improved steadily, with the number of unemployed (aged 15–74) dropping to well under 5 million in 2016 and to under 3.9 million in the second quarter of 20175.

The crisis was a driver of social innovation in that actors had to mobilize civil society to tackle the problems that arose at the time in parallel with the reduction of the welfare state, especially unemployment subsidies and labor activation schemes. Social innovation started to gain importance in the regional strategies of several of Spain’s Regional Autonomous Communities (especially the Basque Country, Andalusia, Catalonia, Asturias, and Navarre), and in the municipalities of Madrid and Barcelona. Support for the development of social innovation in Spain and its regional strategies, as noted by the European Commission [16], has been based mainly on:

The weight of the social economy sector, given that (according to Luca Jahier6): “Un- doubtedly, the social economy7 is a sector which makes a significant contribution to employment creation, sustainable growth and to a fairer income and wealth distribution. It is a sector which is able to combine profitability with social inclusion and democratic systems of governance, working alongside the public and private sectors in matching services to needs. Crucially, it is a sector which has weathered the economic crisis much better than others and is increasingly gaining recognition at the European level” [17].

An increasing number of actors who deal with numerous compelling social issues, such as high unemployment rates among young people, the long-term unemployed, and those at risk of exclusion (Tarifas Blancas, Obra Social La Caixa, Penascal, S. Coop.). Special attention has been paid to issues such as the low level of participation of civil society in public matters, school drop-outs, lifelong learning and the socio-economic and cultural inclusion of immigrants (Instituto de Innovation Social ESADE, FAGEDA). Other significant challenges faced at national level in the medium term include the ageing population and its impact on the health sector, housing and leisure, transport in large cities, access to energy sources, and the social integration of rural areas (Guifi.net, Afables, mYmO).

As far as geographical coverage is concerned, SI stakeholders in Spain are located not just in large cities such as Madrid and Barcelona but also in regions such as Andalusia, where the focus is on socially innovative solutions to energy-related issues, and the Basque Country, which is a trend-setting region in terms of social innovation. The Basque social innovation strategy is one of the most prominent related regional policies developed in Spain. It has long been supported by a pre-existing dynamic, solid social economy sector. Formally promoted by Innobasque8, it has gradually been integrated into a broader regional innovation master plan, known as the Smart Specialization Strategy (RIS3). It has supported the development of a social innovation network, understood as a tool for socio-economic development at regional level, enhancing the application of innovative ideas and practices in the sphere of public management to create social value [19; 20].

As highlighted by the European Commission, a noteworthy role has been played by research institutes working in the social economy and in social entrepreneurship, many of which are run by Jesuit universities (in particular the ESADE Institute for Social Innovation in Catalonia and the University of Deusto in the Basque Country), and are significant actors in the promotion of social innovation in the country.

This paper focuses on a long-lasting, well-established benchmark initiative for employment promotion in the Basque Country: the Penascal Cooperative9, an organization that promotes training, the development of human capabilities and job placement companies. The Penascal Foundation is a benchmark for social integration and job placement, especially for vulnerable people and those at risk of exclusion in the province of Biscay. In the 30 years since its creation (1986-2016), the Penascal Coop. has helped over 35,000

people10, increasing and diversifying its activity in times of both prosperity and crisis. It was set up in the Penascal neighborhood of Bilbao by a group of Catholic priests and educators who were concerned with school dropout rates, the lack of occupational qualifications, high unemployment, and job insecurity resulting from a period of socio-economic crisis and profound changes in the structure of production in Spain.

In a context in which unemployment in the Basque Country rose from virtually zero in 1973 to 22.5% in 198411, job placement programs became key instruments of social action and the 1980s were a time when there was considerable momentum for the establishing of promoters of job placement companies. At least eight such promoters — Penascal Coop., IRSE, Suspergintza, Sartu, Gaztaroa, Euskadi Training Fund, Bagabiltza, and the Association for the Promotion of Gypsies – were created during that period. This was an effort to create mechanisms to protect vulnerable people against poverty and provide more comprehensive measures to supplement the monthly benefits paid under “Social Wages” or ‘Minimum Income Programs’. In the late 1980s the Norabide program and zero-interest loans were set up by Caritas to promote selfemployment.

Penascal Coop. focuses on improving people’s occupational qualifications and personal development. It works mainly in the promotion of education, employment, and business. It stands out for its innovation, continuous improvement, social commitment, personalized attention, the quality of its resources, and the commitment of its staff. Since its start-up, it has emphasized networking with social partners as a key to success. In 2016 Penascal Coop. had eight “job placement companies” registered and actively working in various sectors such as hospitality/catering, plumbing, carpentry, and refurbishment work. These companies combine personalized training and employment programs, offering vulnerable people jobs and employment contracts.

With a commitment to respond to a lifelong learning strategy, the Penascal Coop. became the first Basque center to implement Basic Vocational Training courses and, together with public bodies and companies, to combine training and employment in Dual Training. The cooperative has received several awards, including recognition by the EU presidency in the list of best practices in its report on the fight against poverty and exclusion12. It has been recognized for its work with young people outside the regular education system and the public aid system.

Experience of China. In China the state has encouraged innovation practices in the field of employment service by enacting several policy guides and implementing relevant measures in the last ten years. These policy documents include the National Medium- and Long-term Plan for Technology Development (2006–2020) published by the State Council in February 2006 and the “Deepening the System Reform to Accelerate the Rate of Implementation on Innovation-Driven Development Strategy”13 issued by the CPC Central Committee in 2015. The State Council has also issued “Opinions on Policy Measures for Vigorously Promoting

Public Innovation” to support innovation14. Meanwhile, the government has also made policies to enforce the market-oriented running of business. The central idea of these documents is to enhance entrepreneurship and innovation [23]. At operational level, local governments have made efforts to promote the incorporation of small business, with this policy line being seen as the future direction for economic growth in China [24]. Accordingly, many public and private actors have established programs to facilitate innovation-driven projects for business activities.

The major social innovation drivers at the top level are CPC and the Central Government. The 19th CPC National Congress gave great importance to strengthening social innovation and social management. The report of the 19th CPC National Congress points out that it is necessary to “accelerate the construction of an innovative country” and clarifies that “innovation is the primary driving force for development and the strategic supporter of modern economic system” [25]. The CPC and the central government have also emphasized the construction of social management and service systems at grassroots level. The Party and the government require local government to strive to enhance the functions of urban and rural community service, to strengthen the responsibilities of enterprises, public institutions, and people’s organizations in social management and services. It is also the government’s responsibility to guide social organizations for their healthy development and encourage people to participate in social management to play their basic roles in social innovation.

The second social innovation driver in China is social need. With the development of economy and society, social needs of people are changing. For example, ageing, the low fertility rate, pollution, and the imbalance in development between urban and rural areas are four of the most significant social problems in China, which stimulate the demand for elderly care services, childcare services, female employment services, and social equality. If these demands are not satisfied, more serious social problems will arise which will lead to sharp social conflicts. Hence, new social needs should be satisfied through social innovation, especially in the current diversified, open, dynamic social environment, in which it is easier to diffuse social conflicts, trigger extreme actions, and destroy social harmony. For example, more than 10 thousand people took to the streets to protest at the construction of a waste incineration power plant in Jiaxing city on April 21, 201615. These social needs push the government to consider social innovation as the means to ease the contradictions.

The third social innovation driver in China is the development of technology. With the rise of information technology, new technologies are continuously applied in daily life. This provides a new platform for social innovation. For example, the development of communication technology is the foundation of promoting e-governance, which is a growing, typical example of social innovation. Hangzhou is one of the best examples: It has operated a of “Smart City” program16 since 2016. People in this city can utilize their mobile phones to enjoy more than 60 kinds of services, e.g. services from the local government and medical services, and to pay public transport fares. Thus, the continuous progress of technology is becoming an important driving force for social innovation.

The fourth driver in China is the third sector. Because the main function of the government is administration, it is difficult for the government to undertake all social management affairs, including social innovation. Thus the third sector, which has professional functions, is needed to organize and carry out social innovation. Moreover, the third sector pushes the government to support social innovation based on its own interests. This kind of driver is reflected in collaboration between the government and NGOs, i.e. volunteer organizations and academic organizations. For instance, at community level, volunteer organizations often take on the task of conducting demand surveys and making plans for innovation. Meanwhile, the government provides the funding for the third sector. The functions and effects of the third sector are particularly significant in Zhejiang Province and Jiangsu Province [26].

The most critical of the major barriers to social innovation in China are cost and risk. Innovation is a kind of systematic program which requires quantities of human resources, funding, and time; local governments must consider their financial situation and the cost. Some regional governments have to renounce innovation due to the burden of cost. Furthermore, the barrier of cost always goes hand in hand with risk. Because the rationality of decision makers and innovation participants is limited, and also the environment varies from region to region in such a big country, it is hard to forecast the risk of innovation, and the consequence of failure is more serious than in small countries. Therefore, in the current environment with all its variety and uncertainty, cost and risk are the primary barriers.

The second barrier to social innovation in China comes from the resistance of interest groups. The third sector plays an important role in driving social innovation, but it can also be a barrier because innovation means change that breaks the old balance. Before a new stage of social innovation, a stable power relationship between the third sector and governments has already been formed. The authorities in charge are afraid of losing their own rights and interests and tend to maintain the existing organizational structure and resist any form of innovation. Moreover, the redistribution of resources induces resistance. The interest groups that possess power often regard innovations that reduce their interests as threats. All in all, the process often has a greater impact on the members of the original government agencies and the audience due to the fact that it mainly involves the redistribution of power and resources, which can trigger conflicts. Hence, the process of innovation may harm the interest of the third sector, which then resists social innovation.

The third barrier to social innovation in China lies in culture. Ideology and organizational culture inertia significantly influence the motivation for social innovation, which is typically reflected by the ideology of local government as well as local society. A conservative, backward ideology will have a huge impact on social innovation and influence the development of social management. Simultaneously, organizational culture is a flexible system that can effectively control and coordinate employees. Once formed, regardless of its merits or defects, it will produce a kind of inertia for the new organizational culture to inhibit its development. It can effectively promote the growth and development of an organization under existing conditions, but it will hinder innovation. At present, the “officialbased” ideology has a particularly obstructive effect on social innovation.

The company conducts assessments of various aspects for applicants for this program and then selects companies engaged in the field of the Internet, online education, and online shopping. The management system has adopted the business model applied by residential building construction companies with the focus on a better environment for people’s living with good facilities to attract renters. In the operation of the program the company manager selects applicants by assessing their capacity for business growth [27].

The outcome of the program is remarkable. The building has the advantages of convenient communications and transportation. The program established its basis by providing people who had innovative ideas with services and facilities and eventually reached an incubation rate of 20% (the proportion of renters who have been successful in establishing new companies and developing sustainably) [28]. The program has obtained support from the local government through financial and policy measures. It also cooperates with the mass media and organizes advertising campaigns in order to attract more business structures18. At present, the issue of enhancing the program’s sustainability is being discussed, as it intends to become a selfregulated program so that there will be more chances for young people to get jobs and design innovative projects.

Experience of Russia. Social innovation is a relatively new phenomenon in Russia. In contrast to the situation in the developed European countries, where the impact of civil society is of crucial importance, in Russia it is mainly the government authorities that play a major role in the dissemination of social initiatives, since they acknowledge the significance of their development and promote social activity in the most important areas considered by the government. This is so for several reasons. First, administrative, legislative, financial, and other barriers hinder the implementation of social innovation [6]. An example of such barriers can be found in the fact that innovation policy in Russia is focused on science and technology and there is no legislation that could govern the development of social innovation. Second, Russians have low community commitment. A survey carried out by the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) states that this is the main problem that non-governmental organizations have to face [29, p. 11]. Third, Russian people have a closed mindset which leads them to tend to treat with apprehension any innovations and changes in social circumstances [30].

The first major initiative to support social innovation and, in particular, social entrepreneurship, came from private business, specifically from LUKOIL President Vagit Alekperov, who founded the Regional Social Programs Fund (RSPF) “Our Future” in 2007. In 2011, the Government of the Russian Federation established the Agency for Strategic Initiatives, an autonomous nonprofit organization providing support to nonprofit organizations (NPOs). One of the goals of the Agency is to find promising initiatives in the field of social entrepreneurship in Russian regions. Since 2013, the Agency for Strategic Initiatives has created centers for innovation in the social sphere (CISS), and there are currently about 23 CISS in Russian regions. They are established for the purpose of promoting social entrepreneurship. In practice, however, the priority in providing support is given to small and medium business rather than socially oriented NPOs. A similar tendency to neglect NPOs is observed in the work of the “Our Future” Fund; according to experts, this is because government interests focus on social business rather than on socially oriented NPOs, and also because social entrepreneurship is considered to be similar to small and medium business [31]. At the same time, a study carried out by the Center for Social Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation of the National Research University “Higher School of Economics” (HSE) shows that there is a pronounced social need in the activities of non-profit organizations in the field of social services in Russia; however, this is hampered by the underdevelopment of infrastructure [32].

Despite certain difficulties, social innovation in Russia is being implemented nationwide. According to RSPF “Our Future”, the Fund promoted 187 innovation projects19

in Russia in 2007–2016. However, according to the Agency for Strategic Initiatives, only 1% of entrepreneurs work in the social sphere20. In 2017, at the Second Forum on Social Innovation in Russian Regions, the first Russian social innovation cluster established in the Omsk Oblast was presented21; it includes Russia’s first School for Social Entrepreneurs, the Club of Mentors and Investors, social innovation centers, enterprises, and business structures. The advantages of the cluster include the possibility of minimizing costs and mobilizing resources, expanding the scale of business, ensuring greater stability in the market, etc.

Besides the active participation of the government in providing support for social innovation projects, other major drivers of social innovation in Russia can be pointed out, such as active demand on the part of the people themselves, the growing sector of socially oriented non-profit organizations, and the development of non-state funds to support social initiatives.

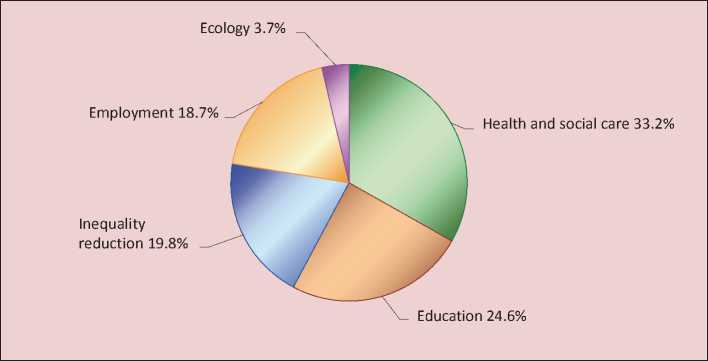

Social innovation in Russia is implemented mostly in areas related to the core functions of the welfare state: health and social care, education, inequality reduction, employment, and the environment (Figure) .

A good example of the Russian social innovation model can be found in the “Mama Works” project, the goal of which is to help women combine work and childcare [33, p. 138]. Employment of women who are on maternity leave is quite an acute issue, because the government has not made much progress in dealing with this problem [6, pp. 73-77].

The history of the project started with an idea to open a social fund called “Road to Life”

Distribution of social innovation projects implemented in Russia, broken down by fields of activity

Source: our own compilations based on the data from the “Our Future” Fund.

in Moscow. Ms. Olesya Kashaeva, the founder of “Mama Works”, was herself a young mother in need of a job, so she tried to find a solution by creating a project that covered several aspects (education, job search, starting a business, psychological support, job creation). The main goal of “Mama Works” is to help young mothers with many children, single mothers, and mothers with children in a difficult life situation get an education, find a job or start their own business (social objectives). “Mama Works” provides psychological support and a certain distraction from domestic chores. The project also provides employment for women on maternity leave both at home and on-site (economic objectives). Under the auspices of the project, a clothing manufacturer called “MamySami” (“moms do it themselves”) has been launched; it produces eco-bags made of cotton22.

The project was established on an altruistic basis, so the support obtained in the initial stages was crucial for its development. This support came from the Greenhouse of Social

Technology, Public Relations Committee of Moscow, Civic Chamber of the Russian Federation, and Moscow Oblast Governor (later, the project received a Presidential grant and won the contest “Social Entrepreneur – 2014”). Currently, the project is funded largely via its own resources. At the moment, the financing for the project is obtained from people’s own resources, which permit microfinancing for business projects by young mothers (to date over 120 business projects have received support) and help for mothers with young children to become successful in business. In addition, “Mama Works” cooperates with the Russian New University within the program “Mamaster”. Education is provided in 11 specialties. In this case, an individual program of full-time studies for young student mothers is drawn up making it possible for them to combine studying and childcare. After completing their education, young mothers are provided with assistance in employment within the specialty that they have obtained23. Since the project started up, more than 3,500 applications have been received from

Table 1. Comparative features of benchmark social innovation initiatives in Spain, China, and Russia

|

Feature |

Spain |

China |

Russia |

|

Social needs and problems which social innovation addresses |

– assistance in finding employment (especially for socially vulnerable population groups); – ageing population; – promotion of business growth and entrepreneurial activity; – educational activity; – poverty and vulnerability or the risk of exclusion; –disadvantaged neighborhoods; – migration (especially low-skilled labor); – enhancement of civic engagement, etc. |

– assistance to young entrepreneurs in starting a business; – employment; – promotion of selfemployment and flexible forms of employment; – improving quality of life; – environmental issues; – educational and medical services; – ageing population; – reducing social inequality, etc. |

– assistance in finding employment (especially for socially vulnerable population groups); – population ageing; – creation of new jobs for socially vulnerable population groups; – training in occupations that are in demand;

|

|

Actors |

– public sector; – private sector; – non-profit organizations; – educational organizations; – scientific research organizations; – private individuals; – companies; – promoting entities, foundations, cooperatives; – networks; and networks of networks |

– public sector; – private sector; – educational organizations; – scientific research organizations;

|

– public sector; – private sector; – non-governmental organizations;

|

|

Drivers |

–social activism; – charismatic and selfless leadership; – favorable legal framework; – cooperation with social partners; – active demand |

– stimulating policy conducted by the government; – financial resources; – human resources; – attention of the media; – active demand |

– support provided by federal and regional authorities and nongovernmental organizations; – active involvement in professional and public associations; – active demand; – financial support; – charismatic leadership; – information and communication technology; – strategic planning of activities |

|

Barriers |

– financial barriers and the need for new funding models; – social awareness and insufficient coverage of activities in the media |

– costs and risks; – resistance on the part of interest groups; – cultural factor (ideology and organizational culture) |

– administrative, legal and bureaucratic barriers;

|

|

Mechanisms of social innovation processes |

The economic crisis helped mobilize civil society to address social problems. At the same time, the traditions of the welfare economy and commitment of the authorities to innovative approaches for addressing social problems have a positive impact on the development of social innovation |

External mechanism: social responsibility of local authorities, universities and some enterprises; Internal mechanism: difficulties in finding employment also force people to handle the issue by themselves (for example, young people decide to start their own businesses) |

The most common are initiatives launched by the state (topdown), but there are examples of successful practices of social innovation related to projects by individual citizens |

End of the Table

|

Role of policy |

– Public policy is of great importance, as the development of social innovation is part of many national and regional normative legal documents on innovation policy |

– Policy, especially at the national level, plays an important role. At the highest level, the central government encourages innovative entrepreneurship, and this encourages the authorities of provinces and municipalities to implement this idea. Due to political support, there are no financial difficulties and barriers on the part of the mass media |

– Provision of support by the authorities is essential, but in many cases it is reduced to the political component; financial instruments are used less frequently. However, there is a possibility of obtaining grants, awards, and subsidies |

|

Source: own compilation based on comparative analysis |

|||

64 Russian regions, and more than 2,400 hours of consultations and training sessions have been delivered. “Mama Works” is interested in expanding its geography, so that moms in any region can participate in the project. It has become an occasion for the development of a social franchise.

Comparative exercise : After this look at the current situation in the area of social innovation through the context of the three successful practices in Spain, China and Russia presented above, the following table (Table 1. Comparative features of benchmark social innovation initiatives in Spain, China, and Russia ) compiles the main features of social needs and problems addressed, the main actors involved, the drivers and barriers boosting or hindering those innovations, the mechanisms of social innovation processes, and the central role played by policy and policy makers in some contexts.

The range of social needs and problems addressed by social innovation initiatives is quite similar in the countries under consideration. They include a wide range of topics such as the promotion of employment (especially among vulnerable population groups), professional development, creation of new jobs, enhancement of entrepreneurial activity, promotion of self-employment initiatives and flexible forms of employment, development of local communities, enhancement of civic engagement, improvement of the quality of life, etc. A particularity detected in Russia is that there are a number of initiatives to enhance the prestige of certain occupations which are considered humble.

Social innovation actors in Spain, China and Russia include a large number of stakeholders from different sectors including companies and banks, non-profit organizations, educational and research institutions, business incubators, government organizations, and co-working communities. The generation of small collaborative eco-systems around a particular problem in a given context is a feature observed in all three cases studied.

As practice shows, public policy is one of the driving forces in the development of social innovation. For example, in Spain, innovation development is focused primarily on technology but in recent years, due to alignment with the “Europe 2020” strategy and the focus on social challenges, social issues have been included as one of the main areas of development. Thus, the “Strategy for science, technology and innovation for 2013–2020”24 has a specific section dedicated to the relevance of social changes and innovations. The strategy aims to strengthen the capacity of actors to promote social progress and competitiveness and takes into account a) the most pressing economic situations; and b) the need for structural reforms, to promote the creation of new jobs and the development of socio-economic and entrepreneurial foundations. In addition, several regions in Spain have specific plans for expanding social innovation initiatives (e.g. Catalonia, Madrid, Andalusia, the Basque Country) [34, pp. 48-49].

Crises, especially in the economy, have had a devastating effect on employment, inclusion and the fight against poverty in many contexts. However, the situations caused by those crisis, have served precisely as a catalyst for social innovation. This fact can be commonly appreciated in many countries and settings. It has also been the case in the three initiatives analyzed, where civil society and individuals have been impelled to tackle certain social issues when the government was not able to cope with them. When dealing face-to-face with a particular problem, people often begin to search for a solution to help other people in similar situations. Thus, active demand from social sectors to solve social problems and/or to cover socio-economic needs also contributes to the development of social innovation.

Another factor conducive to the development of social innovation is the establishment of partnerships, collaborative relationships, and networks, adopting different and evolving forms of stakeholder interactions. This is the case in the Penascal Coop. in the Basque Country (Spain), where a strong collaborative networking ecosystem has been developed to sustain the many interventions carried out by this promoters of job placement companies. In China and Russia the strong influence of the government on the development of social innovation means that there are difficulties in the interaction between public and private actors [35, pp. 99-100]. Thus, promoting activities aimed at facilitating cooperation between the various parties would help further boost social innovation.

Finally, two more features play significant roles in the development and promotion of social innovation: the figure of a charismatic project leader, and the emergence of competitors, which usually helps stimulate and further develop projects, as initiatives need new ideas to adapt or readapt to become more competitive or fight for sustainability.

As regards barriers , lack of funding has been found to be a significant limitation to the development of social innovation. Even in Spain and China, where social innovation is included in various strategic plans, legal documents, and policies, financial support from the government is in many cases insufficient. The fact that society has decided that interventions in the social sphere should be carried out by the government rather than by third parties, social enterprises or social initiatives does not help to direct resources towards civil society, entrepreneurs or stakeholders. Furthermore, in many cases authorities do not have a clear understanding of the nature, results, and impacts of social innovation; this lack of awareness prevents them from allocating enough funding for investing in social innovation solutions.

In Russia there is a possibility of obtaining government subsidies and grants for various social innovation projects, but in practice it is not always feasible. In Spain and some other Southern European countries, new ways of funding such as social exchanges, microcredits, crowd funding, social investing, and development bonds have been explored to develop social innovative solutions, though they are still insufficient to meet demand [34, p. 53]. Some of these funding schemes are currently also being developed in Russia and China.

In addition, Russia faces the obstacles of an underdeveloped regulatory framework for social innovation and social entrepreneurship and the need for better training and improvement of the skills of employees for the development of social innovation activities.

State policy supports China’s social innovation development strategy by promoting the establishment of environments conducive to creative activities. The government has extended access to the registration of non-for-profit and social enterprises, thus providing more opportunities to implement social innovation (through the provision of different types of information and an opportunity to obtain education and training) [35, p. 99].

In China and Russia fewer successful practices are initiated by individuals: the government is predominant in the social innovation sphere, with most social innovation projects being initiated by the state (“topdown”). In Spain, at least in those regions with a longer tradition of social innovations, such initiatives are mainly put forward by enthusiasts and leaders who work in collaboration with public and private stakeholders.

Finally, it is important to emphasize how little attention social innovation receives in the mass media and from the public. This may be one of the reasons for the limited funding dedicated to social innovations and services. Therefore, another way to further develop social innovative solutions is to promote coverage of the results and the impacts of the most successful social innovation projects in the mass media.

Conclusion

This comparative analysis of benchmark social innovations in Spain, China, and Russia concludes by highlighting conditions conducive to the flourishing of social innovations.

Social and technological innovations affect one another and there is a lack of awareness of innovative socio-economic solutions. As a result, different aspects of social innovation are still considered only in light of technological innovations and are not sufficiently recognized as an independent phenomenon. In this regard it is necessary to develop and refine the concept of social innovation so that the authorities, citizens, and stakeholders in general can better understand the potential benefits and impacts of its implementation.

Better provision of government or public support for social entrepreneurship as one of the main facilitators of social innovation could become a significant component of social and regional development. This is especially relevant for Russia, where social entrepreneurship support models are at an incipient stage.

There is a need to focus on people’s needs and enhance their motivation for civic engagement in addressing social issues. At the same time, in both Russia and China more flexible state regulation for social innovation would be conducive to the development of social innovative solutions. With the establishment of social innovation centers and centers for social entrepreneurship, it would be possible to accumulate resources for the development of social innovation more efficiently.

In alignment with the European Pillar of Social Rights [36], the challenge for the coming years in Spain is to promote sustainable Hybrid Value Systems. These systems should be articulated around stabled partnerships between a social organization and a private company or public entity that can generate significant social impact and, at the same time, financial returns for the parties involved.

The key direction for Russia is to form an ecosystem of social innovation; this includes improving interactions between all stakeholders, mobilizing and effectively using resources for the development of social innovation, working out legal and regulatory support, promoting civic engagement, financial and non-financial support for social initiatives, etc. [37, p. 100].

In China action by the government to further promote social innovation should focus on a) investing more resources in society to stimulate the development of social innovation; b) disseminating and raising awareness of the potential of social innovation, encouraging public engagement; and c) developing and improving legislation in the sphere of innovation to protect and regulate relations between innovative sectors; for example, a new tax policy to stimulate corporate innovation and legislation to protect intellectual property.

Список литературы Social innovation in Spain, China and Russia: key aspects of development

- Klimczuk A. Comparative analysis of national and regional models of the silver economy in the European Union. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 2016, no. 10 (2), рр. 31-59.

- Hansson J., Björk F., Lundborg D., Olofsson L.E. An Ecosystem for Social Innovation in Sweden -A Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda. Lund: Lund University, 2014. 44 р.

- Chuvakova S.G. Innovations in social sphere and sphere of employment as base preconditions of modernization of domestic economy. Natsional’nye interesy: prioritety i bezopasnost’=National Interests: Priorities and Security, 2010, no. 17 (74), pp. 75-79..

- The Young Foundation Social Innovation Overview: A deliverable of the project: "The theoretical, empirical and policy foundations for building social innovation in Europe" (TEPSIE), European Commission -7th Framework Program. Brussels: European Commission, DG Research, 2012. Part 1. 43 р.

- Owen R. A new view of society. Essays on the formation of human character, and the application of the principle to practice. London: Cadell & Davies, 1813. Available at: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/pluginfile.php/607280/mod_resource/content/2/a207_12_essay1.pdf.

- Marx K. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1: The Process of Capitalist Production. Translated from the 3rd German edition by S. Moore and E. Aveling. Chicago: C.H. Kerr and Co., 1909. Available at: http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/marx-capital-a-critique-of-political-economy-volume-i-the-process-of-capitalist-production

- Weber M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. Martino Fine Books, 2012. 450 p.

- Durkheim E. The Rules of Sociological Method. New York: The Free Press, 1982. 264 p.

- Drucker P.F. Social innovation, management, new dimension. Long Range Planning, 1987, no. 20 (6), pp. 29-34.

- Young M. The Social Scientist as Innovator. Cambridge, Mass: Abt Books, 1983. 265 p.

- Pol E., Ville S. Social innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 2009, no. 38, рр. 878-885.

- Solov’eva T.S., Popov A.V. Social innovations in employment: a regional perspective. Ars Administrandi, 2015, no. 2, pp. 65-84..

- Richez-Вattesti N., Vallade D. ESS et innovations sociales: quel modèle socio économique d’incubateur? Revue d’innovation, 2009, no. 30, pp. 41-61.

- Bouchard M.J., Klein J.L., Harrisson D. L’innovation sociale en économie sociale. L’innovation sociale émergence et effets sur la transformation des sociétés. Montréal: Université du Québec à Montréal, 2006. Pp. 121-138.

- Osborne S., Brown K. Managing change and innovation in public service organizations. London: Routledge, 2005. 273 p.

- Fernandez M.T., Pineda O.M., Chaves R.A. La innovación social como solución a la crisis: hacia un nuevo paradigma de desarrollo. XIII Jornadas de Economia Critica, 2012, February9-11, pp. 1084-1101.

- European Commission. Social innovation research in the European Union Approaches, findings and future directions. Policy Review. Brussels: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities, 2013. Available at: http://www.net4society.eu/_media/social_innovation.pdf

- Monzón Campos J.L., Chaves Ávila R. The social economy in the European Union. Report drawn up for the European Economic and Social Committee by the International Centre of Research and Information on the Public, Social and Cooperative Economy (CIRIEC). Brussels: Visits and Publications Unit, 2012. Available at: http://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/qe-30-12-790-en-c.pdf

- Bernaola G., Atxutegi G. La innovación social en el País Vasco. De la teoría a la práctica. Revista Española Del Tercer Sector. 2017. Pp. 183-188.

- Innobasque. Informe Opentric, nuestro modelo de innovación. Bilbao, 2011. Available at: https://www.elkarbide.com/sites/default/files/innobasque_1_tr_2011.pdf

- Caro-Gonzalez A. PhD Thesis "Las Empresas de Inserción y sus Entidades Promotoras: tejido social para la inclusión social en el País Vasco". Las Empresas de Inserción y su papel en el proceso de inclusión de la población inmigrante en el País Vasco. University of Deusto, 2015.

- Integrated approaches to combating poverty and social exclusion. Best practices from EU Member States. Hague: Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, 2016, Pp. 32-33. Available at: http://www.effectiefarmoedebeleid.nl/files/3614/6668/9668/WEB_93954_EUNL_Brochure_A4.pdf

- Lin K., Dan B., Yi L. An exogenous path of development: explaining the rise of corporate social responsibility in China. International Journal of Social Quality, 2016, № 6 (1), pр. 107-123.

- Xue J. Operating the strategy of employment first. People’s Tribune, 2017, no. 13, рр. 86-87.

- Feng L., Yuan B. Innovation how the first impetus leads the development (focusing on the Nineteenth Congress Report and changing to the high quality development stage 3). Available at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n1/2017/1102/c1001-29621827.html

- Liao X., Qiu A. The study of dynamic and resistant factors in social management innovation and its countermeasures. Chinese Public Administration, 2013, no. 3, рр. 62-65.

- Wang C. Zhejiang University Wangxin Science and Technology Park: becoming a partner of time. Zhejiang Online, 2015. 7 May. Available at: http://biz.zjol.com.cn/system/2015/05/07/020639709.shtml

- Chen T. Honeycomb-like houses are creating double ecological mass entrepreneurship room. Zhejiang Daily, 2015, 28 May. Available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/local/2015-05/28/c_127849737

- Starostin A.M., Ponedelkov A.V., Shvets L.G. Civil society in Russia in the context of transfer of innovation. Vlast’=Power, 2016, no. 5, pp. 5-15..

- Farakhutdinov Sh.F. Study readiness for innovation in rural areas of the Tyumen region. Regional’naya ekonomika i upravlenie: elektronnyi nauchnyi zhurnal=Regional Economics and Management: Online Scientific Journal, 2016, no. 4 (48), pp. 357-365..

- Moskovskaya A.A., Soboleva I.V. Social entrepreneurship in the system of social policy: international experience and prospects of Russia. Problemy prognozirovaniya=Studies on Russian Economic Development, 2016, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 701-706. DOI: 10.1134/S1075700716060113

- Krasnopol’skaya I.I., Mersiyanova I.V. Transformation of the social sphere administration: demand for social innovations. Voprosy gosudarstvennogo i munitsipal’nogo upravleniya=Problems of state and municipal management, 2015, no. 2, pp. 29-52..

- Shabunova A.A., Popov A.V., Solov’eva T.S. The potential of women in the labor market of the region. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2017, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 124-144. DOI: 10.15838/esc.2017.1.49.7

- Enciso M., Soinu O., Henry G. Southern Europe. Social innovation strategies -regional report. TUDO: Technische Universität Dortmund, 2015. Pp. 42-57.

- Lin K. East Asia. Social innovation strategies -regional report. TUDO: Technische Universität Dortmund, 2015. Pp. 95-101.

- European Pillar of Social Rights 2017. European Commission. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/social-summit-european-pillar-social-rights-booklet_en.pdf

- Solov’eva T.S. The role of social innovations in solving social problems: Russia’s and Belarus’s experience. Belorusskii ekonomicheskii zhurnal= Belarusian Economic Journal, 2017, no. 3 (80), pp. 92-103..

- Leeuw, F., Vaessen, J. (Eds.) Impact Evaluations and Development -Nonie Guidance On Impact Evaluation. Washington: Nonie, 2009. Pp. 21-34.