Social risks of international immigration into Russia

Автор: Borodkina Olga Ivanovna, Sokolov Nikolai Viktorovich, Tavrovskii Aleksandr Vladimirovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 3 (51) т.10, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article explains the sociological theory of immigration risks. Despite the fact that domestic sociology has been recently attracting more attention to the risk theory, risks of migration processes have not yet been properly considered. According to the authors, such a theory must consider social risks for all participants of the migration process: host countries, countries of origin and immigrants. The typological model of immigration risks is based on the theory of integration by H. Esser and F. Heckmann. The model describes how various risks are manifested at the micro, meso and macro level of social reality taking into account the four dimensions of social integration: cultural, structural, interactional and identification. Based on the theoretical model the authors identify several groups of risks for the host population: risks based on local and migrant population interaction at the micro level and perceived risks which can be formed by the media under the influence of certain political forces at the macro level...

Risk, international migration, host countries, donor countries, public opinion, saint petersburg

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223940

IDR: 147223940 | УДК: 316 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2017.3.51.6

Текст научной статьи Social risks of international immigration into Russia

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to intensified migration processes in the postSoviet territory and formed a migration system where Russia is a recipient country. Over the post-Soviet decades, the configuration of migration flows has varied considerably. Forced mass migration of the Russian-speaking population of the former Soviet republics, which, in fact, was repatriation of people coming from Russia and their descendants, is replaced by men-dominated mass labor migration represented mostly by young people from Central Asian and Transcaucasian republics [14; 5]. Thus, in 2016, the share of migrants from Uzbekistan aged 18–39 amounted to more than 70% (Tab. 1).

Table 1. Population of migrants into Russia from major donor countries (more than 400 000 people), distribution by sex and age (as of 5 April, 2016)

|

Country |

Sex |

Age |

Total |

|||||

|

<17 |

18-29 |

30-39 |

40-49 |

50-59 |

60+ |

|||

|

Ukraine |

Male |

177 637 |

407 436 |

354 097 |

252 237 |

173 836 |

85 970 |

1 451 213 |

|

Female |

156 524 |

236 375 |

189 905 |

157 891 |

156 345 |

139 155 |

1 036 195 |

|

|

Total |

2 487408 |

|||||||

|

Uzbekistan |

Male |

75 131 |

729 916 |

315 079 |

226 413 |

71 261 |

10 367 |

1 428 167 |

|

Female |

34 552 |

104 549 |

88 710 |

58 366 |

25 283 |

16 154 |

327 614 |

|

|

Total |

1 755 781 |

|||||||

|

Tajikistan |

Male |

75 067 |

358 384 |

167 347 |

93 717 |

29 116 |

3 699 |

727 330 |

|

Female |

30 783 |

51 301 |

36 309 |

22 290 |

7 953 |

2 570 |

151 206 |

|

|

Total |

878 536 |

|||||||

|

Kazakhstan |

Male |

54 510 |

107 387 |

77 783 |

57 938 |

45 659 |

27 355 |

370 632 |

|

Female |

42 563 |

58 395 |

38 874 |

33 244 |

37 034 |

41 400 |

251 510 |

|

|

Total |

622 142 |

|||||||

|

Kyrgyzstan |

Male |

55 594 |

175 366 |

65 012 |

38 784 |

13 580 |

2 785 |

351 121 |

|

Female |

40 975 |

95 001 |

43 934 |

27 690 |

10 793 |

4 680 |

223 073 |

|

|

Total |

574 194 |

|||||||

|

Azerbaijan |

Male |

36 911 |

110 233 |

76 117 |

60 371 |

41 740 |

13 190 |

338 562 |

|

Female |

31 222 |

46 214 |

31 028 |

30 399 |

26 512 |

14 882 |

180 257 |

|

|

Total |

518 819 |

|||||||

|

Moldova |

Male |

23 765 |

118 008 |

79 841 |

53 010 |

28 948 |

5 619 |

309 191 |

|

Female |

18 146 |

51 498 |

37 608 |

31 847 |

21 648 |

8 011 |

168 758 |

|

|

Total |

477 949 |

|||||||

Compiled from data from General Administration for Migration Issues under the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation.

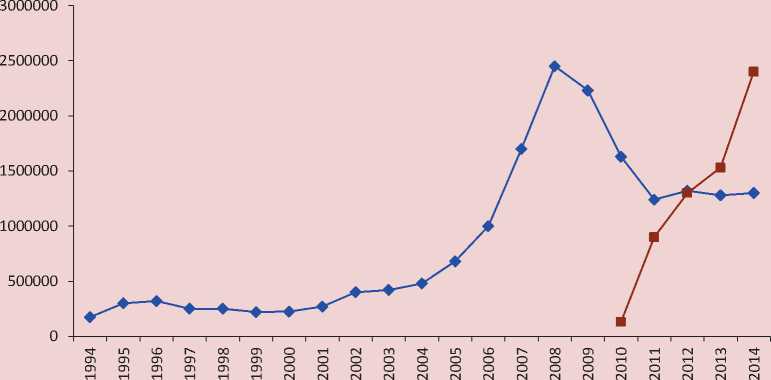

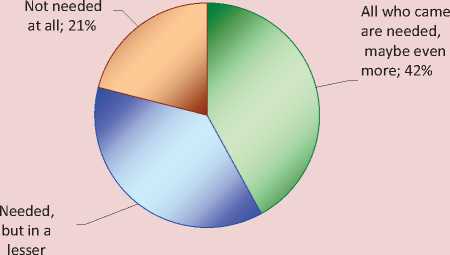

By the mid 2000–s the share of Russians and other ethnic groups of Russia in net migration significantly reduced, reaching in 2007 36.8% (Fig. 1) ; labor migration, by contrast, became mass: for example, the number of issued work permits and patents in 2014 amounted to 3689.9 million (Fig. 2) .

Labor migration is primarily reflexive in its nature; however, a significant number of labor migrants legally or illegally settle in Russia. Presented data indicate a large scale of migration flows into Russia. It is also necessary to consider undocumented labor migration, which, according to experts,

Figure 1. Share of ethnic groups in Russia (including Russians) in net migration, %

■ _ ■ Peoples and ethnic groups in Russia (share in net migration, %) ■ __ ■ Including Russians, %

♦ Net migration, thousand

Note. The ethnical composition of migrants was recorded since 2007.

Source: compiled from Rosstat data.

Figure 2. Number of issued labor permits and patents

♦ Number of issued labor patents — ■ —Number ofissued patents!

Note. Labor patents for private individuals are issued since 2010.

Source: compiled from the Federal Migration Service of Russia (FMS).

can be calculated taking into account the correction coefficient 1.8 [13, p. 26].

Despite high mobility and adaptability, young people, as opposed to people from other age groups, have an insignificant amount of social, cultural and economic capital, which is largely related to the difficult socio-economic situation in donor countries. In modern Russia, young migrants face the problem of social integration in its cultural, structural, interactional and identity environment [23; 26]. Apart from lack of capital on the way of social integration migrants face a number of barriers: institutional (contradictory and restrictive nature of migration policy and legislation, underdeveloped law enforcement in relation to migrants’ rights, spread of corruption among inspection bodies, speculation on migration in political and media discourse), interactive (discriminatory actions of the host population, including radical anti-immigrant social movements) and cultural (xenophobia of the host population, ethnocentric and racist bias).

Lack of capital and barriers to integration of young migrants result in new social inequalities which are formed during the processes of exploitation, hierarchization, ethnic stratification, segregation and marginalization. New social inequalities limit the migrants’ access to vital resources, make it difficult or completely impossible for them to participate in many important spheres of the host society, and are even dangerous to their lives [40]. Inequalities arise in economy, education, social security, healthcare, housing, culture, and politics.

This situation is fraught with increasing social risks considered as the possible negative consequences which will, with a certain level of probability, can affect all participants of the migration process: migrants themselves, donor communities and the host community. Migration problem is becoming increasingly complex, which is a challenge to the social sciences requiring the implementation of a complex approach taking into account the relations between the host community, the donor countries, as well as the interests, rights and practices of migrants themselves. The prospect of social risks can give additional impetus to studying new social inequalities and concepts of migrant integration.

The scientific novelty of the present study lies in the fact that we first carried out the synthesis of theories of risk and theories of social migrant integration. Based on theoretical synthesis, we developed a unique typological model of social risks of international immigration into Russia and studied the perception of migration risks by the population of Saint Petersburg.

Social risks of international migration: conceptual approaches

The most important role in the study of social risks of international migration belongs to the theory of risk formed in the social sciences in the 1980–s and is primarily associated with researchers such as N. Luhmann, U. Beck, E. Giddens, and M. Douglas. These authors emphasize the importance of the social, political and cultural context within which risks are produced and perceived. N. Luhmann points to the increasing uncertainty in all spheres of the modern society and associates risks with making a decision in situations implying choice, where negative consequences are possible. He introduces a meaningful distinction. If a possible loss correlates with the decision this is considered a risk, if it is related to external causes, i.e., with the environment, then we are dealing with danger [28, p. 21–22].

A. Giddens and U. Beck explain the emergence of the risk society with modernization process which focuses on the future and enhances social reflexivity [2]. M. Douglas emphasizes the role of politics and culture in the selection of risks significant for society [22].

According to some sociologists such as O.N. Yanitskii, modern Russian society lacks reflexivity, which is manifested in its inability to adequately and timely assess the situation, social changes and react to them. Underdeveloped social reflexivity of contemporary Russian society leads to insufficient understanding of risk and ultimately reinforces the risk-driven nature of Russian society [16; 17].

The study of migration processes in global science is interdisciplinary. The present study adopted a broad understanding of migration as a complex, multi-level, long-term process of social and cultural transformation of individuals and groups. Let us highlight the areas most relevant for this study. In the context of the theory of migration processes, D. Massey synthetic theory of international migration is still relevant [30]. It integrates six theories: the theory of neoclassical economics [41], the new economic theory of labor migration [39], the theory of segmented labor market [34], the theory of world systems [37], the theory of social capital and migrant networks [20; 31], and the theory of cumulative causation [29]. Massey synthesis helps answer some fundamental questions: what structural factors in developing countries promote emigration and what factors create demand for migrants? What are the motivations of people who, being influenced by these macro-structural factors, decide to move from one country to another? What institutional structures are established in the process of international migration for maintaining international mobility and how they affect migration? And finally, how will the government respond to migrant flows and how efficient is the migration policy?

In addition, to understand migration processes in the post-Soviet environment, in particular the Eurasian integration, it is advisable to consider the theory of migration systems [27; 24]. The theory refers to a broad historical context which shaped the formation of social structures that emerged in the course of sustainable political, economic and cultural correlations between two or more communities.

Under the influence of globalization processes the described theories are adjusted relatively new studies of transnational migration and transnational space. They critically reinterpret old concepts of borders, nations and communities, re-identify the relations between the global and the local, and at focus on the concepts of de-territorialization and global space, networks and flows – of people, goods, services, capital, technology and ideas, which cross national and regional boundaries (D. Harvey’s concept of time space compression, M. Castells and J. Urry theory of environmental flows, A. Appadurai’s theory of scapes). The study of how individuals and groups move across regional and national boundaries during economic globalization, creating new transnational spaces and relations is developed within the concept of transnationalism [38; 33]. It emphasizes that migrants are in two social worlds simultaneously – the society of origin and the host society – and maintain close relations with their homeland by participating in its economic, political and cultural life [19]. The concept of transnationalism has recently been subjected to critical reconsideration [42].

Another important research area is the study of migrant inclusion into the host society. To understand this process, social sciences formed a separate semantic field: absorption, adaptation, acculturation, assimilation, inclusion, incorporation, and finally, integration. Latest research reconsider many of these concepts. Thus, the classical understanding of assimilation (M. Gordon) was reinterpreted by R. Alba, L. Nee, H. Gans, and R. Brubaker [18; 25; 21], while A. Portes, M. Zhou and R. Rumbo proposed a theory of “segmented assimilation”, according to which children of migrants assimilate themselves in different segments of the host society, which depends on both characteristics of the representatives of the second migrant generation and the characteristics of these segments.

It should be emphasized that migration in Russia remains on the periphery of western studies. In turn, Russian research of migration is predominantly empirical. However, it has laid a solid foundation for studying contemporary migration situation in Russia. Among recent works we note studies of migration processes by A.G. Vishnevskii [5], works by V.I. Mukomel, V. Malakhov, E. Varshaver etc. on problems of migrants’ adaptation and integration [9; 8; 3], analysis of migration risk by Zh.A. Zaionchkovskaya, D.V. Poletaev, Yu.F. Florinskaya, etc. [7], the study of V.I. Mukomel, K.S. Grigor’eva on the migration policy [10], work by S.V. Ryazantsev on labor migration [11; 12; 13], the study of citizenship by O.S. Chudinovskikh [15] and transnational relations by S.I. Abashin [1].

Within our approach, the most promising is the theory of social integration by H. Esser [23] developed in works by F. Heckmann [26]. The representatives of this approach distinguish four dimensions of social integration: cultural, structural, interactional and identity, specifying the integration barriers and the consequences of (dis)integration for the processes of social structuring and differentiation. This theory is used not only in empirical studies of integration, but also for monitoring and evaluation of migration policies [4].

Let us consider the main groups of risks for participants of migration process, which may occur at the micro, meso and macro levels of social reality. Our allocation of groups of risks is based on four dimensions of social integration, as proposed in the model of H. Esser and F. Heckmann.

First, we select a group the risks which migrants themselves face ( Tab. 2 ). These risks can be manifested in the labor and housing

Table 2. Types of social risks for migrants depending on dimensions of social integration and level of social reality

|

Level of social reality |

Dimensions of social integration |

|||

|

Cultural |

Structural |

Interactional |

Identity |

|

|

Micro |

On the part of the host community: xenophobia, ethnocentric and racist prejudice, stigmatization; on the part of migrants: lack of linguistic, communicative, legal competence, low or absence of professional qualification |

Absence of recognition and respect, establishment of status hierarchies, loss of status, discrimination |

Relationship with the host community: communicative failure, failure of interaction, conflicts, violence; relationships with the community of origin: weakening or breaking social ties |

Marginalization |

|

Meso |

Xenophobia, ethnocentric and racist prejudice, stigmatization |

Limited access to host communities, social networks and organizations; institutional discrimination |

Distrust; inter-group conflicts and violence; radical anti-immigrant social movements |

Exclusion, segregation from the host community, social networks, organizations, self-isolation of migrant communities, social networks and associations |

|

Macro |

Xenophobia; ethnocentric and racist prejudice; stigmatization; speculating on migration in political and media discourse |

Hierarchization, ethnic stratification, exploitation, contradictory, restrictive migration policy and legislation; loss of legal status, criminalization; underdeveloped institutions for support and protection of migrant’ rights, institutional discrimination |

Corruption among inspection bodies, institutional violence, expulsion, deportation |

Exclusion, segregation from the host society; isolation of migrant communities |

|

Source: compiled by the authors. |

||||

market, education and health, as well as in their everyday life.

The second group of risks is related to donor communities . At the macro level, these are risks associated with the outflow of most active groups of working-age population, especially young people, and the resulting changes in the economy and the sociodemographic structure. Economies of donor communities depend more on migrant remittances and less on domestic resources, technological innovation and creation of new jobs. Moreover, the so-called “brain drain”, i.e. emigration of skilled specialists is accompanied by specific risks. In addition, gender and generation balance is disrupted, which leads to changes in family structures, gender relations and socialization processes at the meso and micro level.

Finally, the last group of risks is related to the host community. The most significant risk at the macro level is probably the risk of developing new forms of social inequality, the emergence of a new lower class represented by low-skilled migrant workers with limited labor and social rights, as well as by undocumented migrants deprived of most rights. This situation is fraught with the development of ethnic stratification, ethnization of social issues and the strengthening of the rightist anti-immigrant attitudes both on the agenda of political parties and within anti-immigrant social movements. Conflict opposition of the majority and the minority, new social inequalities directly challenge social cohesion of the society. The situation may be complicated by conflicts between different groups of migrants, which leads to increasing violence in the host society.

In the social context, it is important, on the one hand, to distinguish the risks based on experience of local and migrant population interaction at the micro level: for example, risks associated with low quality of services provided by migrants, risks of lower educational level in schools attended by migrant children, risks of behavioral conflicts due to the difference in cultural standards.

On the other hand, one should consider perceived risks formed by the media under the influence of certain political forces at the macro level. This group includes, for example, perceived risks of labor market competition and dumping, health risks associated with the image of migrants as carriers of dangerous diseases, as well as risks based on the idea of widespread violence and delinquency among migrants.

To sum up the theoretical part, it can be argued that cross-border migration, being one of the strategies for reducing the risks of households in donor communities, creates new risks for both donor and host communities and for migrants themselves. For example, lack of migrant human and labor capital is a serious risk on the one hand, on the other hand – it is created by situations of uncertainty in the process of gaining legal status, on the labor market, in education, healthcare, everyday interactions created by risky decisions of various actors of the host society.

Research methods

The empirical base of the research includes results of the public opinion poll conducted in Saint Petersburg for assessing migration in the city and identify migration risks in the minds of the host population. Saint Petersburg is one of the most attractive cities for international labor and education regional migration; the situation in this city does not cover the whole variety of migration risks, yet it reflects the main ones well enough.

The authors used standardized telephone interview as a method of data collection. The choice of the method is explained by the fact that telephone surveys are optimal for quick scanning of public opinion in major cities such as Saint Petersburg. An additional motive of using telephone interviews is presence of longitudinal data previously collected with the use of this method.

The questionnaire included 40 questions on the situation in the city, interaction of Saint Petersburg citizens with migrants in various spheres of life, assessment of positive and negative consequences of migration, efficiency of institutional control over the process, attitude towards various variants of strategies of migration control and migration policy, as well as 6 questions on the respondents’ demographic, economic and social status. Most of the questions were semiclosed with the answer variant – “other”. Assessment variables were represented by specially designed verbal ordinal scales presenting key options within a possible range of statements. Simpler questions were accompanied by the Likert Scale. We also used the technique of Likert-type scale which helps identify the respondent’s attitude by total assessment of a series of indicators.

The general population of the study includes residents of Saint Petersburg aged 18 and over. The stratified sample was proportionally distributed among 18 municipal districts the city. The selection of telephone numbers from the urban total urban subscriber base was randomly carried out by the CATI system with the help of special software based on the use of a random number generator.

The interviews were conducted only via telephones in residential areas (by respondents’ place of residence). Selection of respondents by a particular phone number was limited by sex and age. The filling of territorial and demographic sampling structure was controlled automatically – as the district sub-samplings and demographic categories were fully filled.

The total sampling size included 1017 people, which provides the margin of random sampling error Δ =3.1% for a 95% confidence probability.

Data input was carried out during the interview by using interactive forms of CATI system. Data processing was performed using the SPSS program, version 16.0. Data visualization was performed using MS Excel (figures) and MS Word (tables). Adjoint matrices were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-squared test and the method of standardized residuals. During analysis, data were partly grouped into larger semantic categories – categorical and soft answers were combined in the Likert Scale, dichotomous variables were created based on the selection of certain answer choices in complex verbal scales.

Results of a telephone survey of Saint Petersburg residents

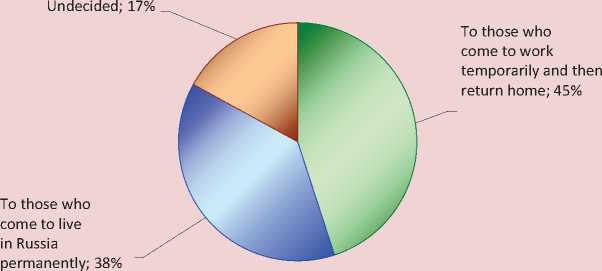

Analysis of public reflection at the macro level – people’s attitude towards migration as a phenomenon and migrants as undivided troops – has indicated that the Saint Petersburg community is dominated by restrained assessment amid quite a wide range of approach differentiation. The modal response to the question “Are migrants in Saint Petersburg needed today?” was “needed, but in a lesser amount” – 34.1% of the respondents. The second largest category of residents (30.3%) admit that the current number of migrants remains but is against its increase. Only 7.5% of residents in Saint Petersburg welcome an increase in the number of migrants in the city (“They are needed, it is necessary that migrants continue to arrive to Saint Petersburg”). And one in every five respondents (18.8%) is against them – “migrants are not needed in Saint Petersburg – those who came should leave”. A relatively small share of respondents who were undecided (5.7%) is noteworthy, as well as the share of those who has their own variant (mostly differentiated) (3.6%). This suggests that the issue of migration in the host community is discussed and some attitudes have already been formed.

In-depth analysis indicated that the categories of those in favor of preserving the status quo and increased migration have similar attitudes to other options and thus can be combined. On the contrary, the attitudes of those who admit the presence of migrants if their number is reduced are significantly different from the attitude of complete exclusion of migrants. Therefore, the area of definite opinions [6, p. 100] contains three basic points of view ( Fig. 3 ). The majority of respondents is in favor of reducing the number of migrants (52.9% of the total number of respondents, 58.3% of the number of respondents who expressed definite opinion), but this majority did not develop any general (dominant) attitude at the time of the study. In practice we are talking about a wide range of expectations – from reducing the number of separate problem representatives to excluding all migrants without exception.

The second indicator characterizing the position of the host community at the macro

Figure 3. Distribution of answers to the question “Are migrants needed Saint Petersburg today?” (% of respondents to this question)

amount; 37%

level – their attitude towards possible amnesty for illegal migrants. Given the projective nature of the assessment object, during the interview it turned out that we are talking about an offer “to allow illegal immigrants to stay and work in Russia if they respect the law and pay taxes”. Analysis has indicated that dynamics of this indicator is largely similar and related to those discussed above. The shares of those who had difficulties answering these two questions are near the same (8.5%), among those who gave a definite answer the share of those against amnesty is slightly higher (48.8% of the total sampling, 53.3% of those who expressed a definite position). A high share of residents strongly against amnesty for illegal migrants is noteworthy, amounting to 31.2% of respondents. Thus, opponents of amnesty constitutes 2/3 of those who are “definitely against” it. The supporters of amnesty, by contrast, have a moderate attitude (26.5% of answers “more likely to support” of 42.8% of respondents in favor of amnesty).

Cross-sectional analysis demonstrated the correlation between the distributions reflecting social attitudes towards the city’s need for migrants and amnesty for illegal immigrants ( Tab. 3 ). Analysis of the adjoint matrix by using the method of standardized residuals made it possible to identify statistically significant shifts in proportions of distribution of supporters and opponents of amnesty in two categories of citizens opposing each other – those who admit the preservation and/or increase in the number of migrants in Saint Petersburg, and those against their presence in the city. The modal category of respondents (“migrants are needed, but in lesser amounts”) voted against amnesty in proportions very close to the average in the sampling.

Table 3. Correlation between attitudes towards the need for migrants in Saint Petersburg and towards possible amnesty for illegal migrants (% of respondents by category)

|

Attitude towards possible amnesty for illegal migrants |

Are migrants needed in Saint Petersburg today? |

||

|

All who came are needed, maybe even more |

Needed, but in a lesser amount – their number should be reduced |

Not needed at all, those who came should leave |

|

|

Support amnesty |

59.8 |

42.2 |

24.6 |

|

standardized residual |

3.9 |

-0.9 |

-4.2 |

|

Against amnesty |

40.2 |

57.8 |

75.4 |

|

standardized residual |

-3.6 |

0.9 |

3.9 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

The presented observations help draw two interim conclusions. First, migrants are mostly associated in the collective consciousness with illegal migrants and migration in general is probably related to illegal migration. In this case we observe how the media construct social issues, as, from the point of view of its impact on the everyday life of the host community; the legal/illegal status of a migrant is a secondary factor and is derived from effectiveness/ineffectiveness of government control mechanisms. Second, the host society in fact demonstrates two opposing attitudes towards the migrant population: the first lies in accepting everyone and probably even stimulating migration, the second – in eliminating it completely. The intermediate attitude – to reduce and maintaining the number of migrants – is in fact a compromise. Its prevalence in the mass consciousness indicates under-established public attitude towards migration as a phenomenon.

The third indicator at the macro level used in the analysis is the selection of migration priority for the host community. Respondents were asked who should be given priority when issuing visas, stay or work permits: those who immigrate for temporary work or those who plan to stay and live in Russia permanently? Just like in the case of amnesty for illegal immigrants, the respondents were divided into two similar-sized groups with a slight advantage of those supporting temporary stay ( Fig. 4 ). However, in this case the share of those who were undecided is much higher (17%), which suggests that such “subtleties” of the migration process are less frequently discussed.

Analysis of the system of three macro-level indicators indicates that, although migration themes are familiar to the Saint Petersburg community, it is too early to talk about the shaped public attitude in this respect. This is evidenced by almost equiprobable distribution

Figure 4. Distribution of answers to the question: “Who, in your opinion, should be given priority when issuing visas, stay or work permits: those who immigrate for temporary work or those who plan to stay and live in Russia permanently?” (% of the total number of respondents)

of respondents among key alternatives and the modality of compromise positions. Petersburgers still widely perceive migrants as temporary workers and focus on their formal status (legal or illegal). Public reflection is lagging behind the objective process of transformation of host communities, which leaves this process beyond social control and produces risks at the macro level.

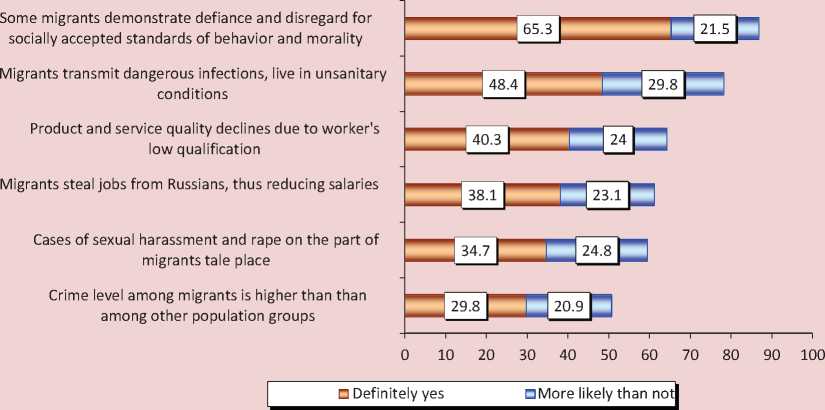

How do macro-level trends correlate with data of meso and micro level indicators? Let us turn to the assessment of migration risks by urban community: 50–87% of respondents confirmed different threats resulting from the presence of migrants in Saint Petersburg ( Fig. 5 ).

However, analysis of the structure of the issues the citizens associate with the presence of migrants arises new questions. The major issues are related to migrants’ way of life: immoral behavior, disregard for local cultural standards and “dirty” life. Why are these moments significantly ahead of the functional competition on the labor market and loss of quality and technological culture? The latter threaten to cause real material damage, whereas the former are more symbolic. Why did lower positions in the risk ranking turn out to be the most socially dangerous – violent crimes and sexual aggression? It is after such events that mass unrest associated with migrant population takes place.

Figure 5. Citizen’s verification of risks of the host community

(the share of affirmative answers to the question: “Which of the following statements do you agree with?”) (% from the total number of respondents)

One of the possible explanations is that the host society gives priority when interpreting the migration phenomenon to cultural capital and goals, whereas economic capital and security issues remain on the periphery of public attention. Then the cultural distance between the host society and migrants representing various donor communities may be a determining factor which builds the whole system of interaction including economic cooperation and competition, and even conflicts in the form of violence.

To characterize the migration situation at the micro level the authors firstly present two indicators reflecting population’s involvement in the most acute interactions related to violence and sexual aggression. In this case, the technique suggests gender differentiation of indicators. Male respondents were asked of they ever personally participated in fights with migrants or other conflicts involving violence or threat of violence. Women respondents were asked if they personally happened to be a victim of sexual harassment or violence on the part of migrants. According to the survey, 18.5% of men and 9.4% of women gave an affirmative answer.

The share of people involved in acute conflicts with migrants is significantly higher among the youth. Almost every third man under 30 years (29.7%, standardized residue 2.6) reported they had experience of violent interaction with migrants. Every fifth woman in the same age group (21.3%, standardized residual 4.3) has at least been harassed by migrants.

Experience in acute conflict interaction significantly enhances the issues of the migrant population. Thus, half of men personally involved in fights and other violent interactions (49.4%, standardized residual 2.7) confirm that the crime rate among migrants is higher than among other population groups. The majority of women ever subjected to sexual aggression (54.5%, standardized residual 2.6) clearly verify their perceive migrants as a potential source of such aggression.

Thus, the study demonstrates a high level of social risks for the part of the host community included in their daily interaction with migrants. Their reaction to the elevated level of risk is probably ignoring of problem aspects of the migration process, its assessment and establishing specific social attitudes. Community members are afraid of being personally involved in the migration process and “do not notice” the presence of migrants in their everyday life, “do not get involved” with their work and life, focusing only on a very general view of the events which they are actually part of.

Conclusion

The present study made an attempt to outline the sociological theory of migration risks. Despite the fact that domestic sociology has given much attention to the theory of risk in recent years, risks of migration processes have not yet been properly considered. We believe that the heuristic value of the proposed theoretical model is that it helps highlight and demonstrate the correlation between various groups of migration risks for all participants of the migration process in the host countries, the countries of origin and for migrants themselves. The theoretical model of migration risks is based on the theory of integration by H. Esser and F. Heckmann. The authors made an attempt to describe how various risks are manifested at the micro, meso and macro level of social reality taking into account the four dimensions of social integration distinguished by Esser and Heckmann.

Of course, it is impossible to explore all categories of risk possible to be selected by the model in one study, therefore only two groups of migration risks of the host population were chosen for empirical study: the actual risks of interaction at the micro level and the perceived risks formed by the media under the influence of certain political forces at the macro level. These groups of risk were studied with the help of public opinion survey of residents of Saint Petersburg, which provides a good basis for further comparative studies on both Russian and international scale.

The present study demonstrates the importance of cultural distance between the host and migrant population, which is manifested in increased attention to the perceived threat to the standards and values of the local population, whereas risks associated with labor market and violence, remain on the periphery of public attention. There is also a high level of social risks for the part of the host community involved in daily interaction with migrants.

In our opinion, analysis of social risks of international migration should be of high priority in sociology of risk and sociology of migration. Moreover, this issue may become an independent area in risk and migration theories.

Список литературы Social risks of international immigration into Russia

- Panarin S. (Ed.). Abashin S. I zdes', i tam: transnatsional'nye aspekty migratsii iz Tsentral'noi Azii v Rossiyu . Vostok na Vostoke, v Rossii i na Zapade: transgranichnye migratsii i diaspory . Saint Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya, 2016. Pp. 159-176..

- Bek U. Obshchestvo riska. Na puti k drugomu modernu . Moscow: Progress-Traditsiya, 2000. 383 p..

- Varshaver E., Rocheva A., Kochkin E., Kuldina E. Kirgizskie migranty v Moskve: rezul'taty kolichestvennogo issledovaniya integratsionnykh traektorii . Moscow: RANKhiGS, Tsentr issledovanii migratsii i etnichnosti, 2014. 153 p..

- Wilkens I. Integratsionnyi monitoring v Germanii. Empiricheskoe issledovanie protsessov integratsii immigrantov (na primere federal'noi zemli Gessen) . Trudovaya migratsiya i politika integratsii migrantov v Germanii i Rossii . (Edited by Rozanova M.S.). Saint Petersburg: Skifiya-print, 2016. Pp. 119-140..

- Vishnevskii A.G. Vvodnaya stat'ya. Novaya rol' migratsii v demograficheskom razvitii Rossii . Migratsiya v Rossii. 2000-2012: khrestomatiya v 3 tomakh . Vol. 1, ch. 1. Moscow: Spetskniga, 2013. 880 p..

- Gavra D.P. Obshchestvennoe mnenie kak sotsiologicheskaya kategoriya i sotsial'nyi institut . Saint Petersburg.: ISEP RAN, 1995. 350 p..

- Zaionchkovskaya Zh.A., Poletaev D.V., Florinskaya Yu.F., Mkrtchyan N.V., Doronina K.A. Zashchita prav moskvichei v usloviyakh massovoi migratsii . Moscow: Tsentr migratsionnykh issledovanii, 2014. 118 p..

- Malakhov V. Integratsiya migrantov: kontseptsii i praktiki . Moscow: Mysl', 2015. 272 p..

- Mukomel' V.I. Adaptatsiya i integratsiya migrantov: metodologicheskie podkhody k otsenke rezul'tativnosti i rol' prinimayushchego obshchestva . Rossiya reformiruyushchayasya: Ezhegodnik . Moscow: Novyi khronograf, 2016, issue 14, pp. 411-467..

- Mukomel' V.I., Grigor'eva K.S. Novatsii v rossiiskom migratsionnom zakonodatel'stve v kontekste pravoprimeneniya . Migratsionnoe pravo , 2016, no. 2-3..

- Ryazantsev S.V. Trudovaya immigratsiya v Rossiyu: effekty ili riski dlya strany? . Rossiya v novoi sotsial'no-politicheskoi real'nosti: monitoring vyzovov i riskov , 2013, no. 1. Moscow: ISPI RAN. Pp. 124-137..

- Ryazantsev S.V., Skorobogatova V.I. Inostrannye trudovye migranty na rossiiskom rynke truda i novye podkhody k migratsionnoi politike . Ekonomicheskaya politika , 2013, no. 4, pp. 21-29..

- Ryazantsev, S.V. Nedokumentirovannaya trudovaya migratsiya v rossiiskoi ekonomike . Vestnik Tyumenskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Sotsial'no-ekonomicheskie i pravovye issledovaniya , 2015, vol. 1, no. 1(1), pp. 24-33..

- Tyuryukanova E. Trudovaya migratsiya v Rossiyu . DemoskopWeekly, 2008, no. 315-316. Available at: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2008/0315/tema01.php..

- Chudinovskikh O.S. O politike i tendentsiyakh priobreteniya grazhdanstva Rossiiskoi Federatsii v period s 1992 po 2013 g. . Demograficheskoe obozrenie , 2014, no. 3, pp. 65-126..

- Yanitskii O.N. Modernizatsiya v Rossii v svete kontseptsii «obshchestva riska» . Kuda idet Rossiya? Obshchee i osobennoe v sovremennom razvitii (ed. by Zaslavskaya T.). Moscow, 1997. 368 p..

- Yanitskii O.N. Sotsiologiya riska: klyuchevye idei . Mir Rossii , 2003, no. 1, pp. 3-35..

- Alba R., Nee V. Rethinking assimilation theory for a new era of immigration. International migration review, 1997, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 826-874.

- Bauböck R. Towards a Political Theory of Migrant Transnationalism. International Migration Review, 2003, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 700-723.

- Boyd M. Family and Personal Networks in International Migration: Recent Developments and New Agendas. International Migration Review, 1989, vol. 23, pp. 638-670.

- Brubaker R. The return of assimilation? Changing perspectives on immigration and its sequels in France, Germany, and the United States/R. Brubaker. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2001, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 531-548.

- Douglas M., Wildavsky A. Risk and Culture. An Essay on the Selection of Technical and Environmental Dangers. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982. 221 p.

- Esser H. Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 2: Die Konstruktion der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt-New York: Campus, 2000. 511 p.

- Fawcett J.T. Networks, Linkages and Migration Systems. International Migration Review, 1989, vol. 23, pp. 671-680.

- Gans H.J. Toward a Reconciliation of "Assimilation" and "Pluralism": The Interplay of Acculturation and Ethnic Retention. International Migration Review, 1997, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 875-892.

- Heckmann F. Integration von Migranten. Einwanderung und neue Nationenbildung. Heidelberg: Springer VS, 2015. 309 p.

- Kirz M.M., Lim L.L., Zlotnik H. International Migration Systems: a Global Approach. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1992.

- Luhmann N. Risk: A Sociological Theory. New York, 1993. 236 p.

- Massey D.S. Social Structure, Household Strategies, and the Cumulative Causation of Migration.

- Population Index, 1990, vol. 56, pp. 3-26.

- Massey D.S., Arango J., Koucouci A., Pelligrino A., Taylor E.J. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. 376 p.

- Massey D.S., Goldring L.P., Jorge D. Continuities in Transnational Migration: An Analysis of 19 Mexican Communities. American Journal of Sociology, 1994, pp. 1492-1533.

- Morawska E. In Defense of the Assimilation Model. Journal of American Ethnic History, 1994, vol. 13, pp. 76-87.

- Ong A. Flexible Citizenship. The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham, 1999. 336 p.

- Piore M.J. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Society. Cambridge: CUP, 1979. 229 p.

- Portes A., Rumbaut R.G. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 430 p.

- Portes A., Zhou M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1993, vol. 530, pp. 74-96

- Sassen S. The Mobility of Labor and Capital: A Study in International Investment and Labor Flow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. 240 p.

- Schiller N.G., Basch L., Blanc-Szanton C. Towards a Transnational Perspective on Migration: Race, Class, Ethnicity and Nationalism Reconsidered. New York, 1992. 259 p.

- Stark O. The Migration of Labor. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell, 1991. 416 p.

- Therborn G. The killing fields of inequality. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013. 180 p.

- Todaro M.P. Internal Migration in Developing Countries. Geneva: International Labor Office, 1976. 112 p.

- Waldinger R. The Cross-Border Connection: Immigrants, Emigrants, and Their Homelands. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015. 240 p.