Socio-demographic characteristics and quality of employment of platform workers in Russia and the world

Автор: Chernykh Ekaterina A.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Global experience

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.14, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Digitalization of all spheres of life, technological, demographic, social, and other development drivers of the world contribute to the growing scale and depth of platform employment spread. Emergence of digital platforms was a major challenge for organizing and structuring the labor market. Platforms change not only existing business-paradigms, but the employment model. Platform employment in fact becomes a new institutional mechanism on the labor market. We used general scientific methods in the research: system analysis, comparison, description, generalization, systematization, formalization, and special methods - source analysis, SWOT-analysis, expert evaluation method, etc. The purpose of the research is to select and study socio-demographic features of platform workers in Russia and in the world, to compare them and reveal impact of these features on quality and stability of employment among platform workers. The article analyzes, systematizes, and sums up the results of recent European and American studies on socio-demographic features of platform workers. We attempt to assess similar characteristics among Russian workers (freelancers) analyzing sociological surveys and interviews. The author reveals primary signs of this employment type and their impact on quality of workers’ labor, compare the features of Russian and foreign platform workers, and conclude that pros and cons of platform workers are unevenly distributed, and experience of platform workers is polarized. It creates real problems for some workers and provides opportunities for others. Moreover, we designate risks of platform employment, which is a consequence of its instability, and propose areas for further studies.

Digital labor platforms (dlp), platform employment, platform workers, regulation of platform employment, quality of employment, employment status, precarious employment, work with multiple performers, work on demand

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147234734

IDR: 147234734 | УДК: 331.52 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2021.2.74.11

Текст научной статьи Socio-demographic characteristics and quality of employment of platform workers in Russia and the world

The relevance of our present study is due to the fact that under the impact of numerous economic and social challenges, over the past decades, the scale of platform employment in the world is increasing and its impact on the economy is growing. Digital labor platforms (DLPs) are altering and re-structuring labor markets, changing not only business practices, but also the employment model itself. DLPs are defined as digital networks that coordinate labor service transactions according to certain algorithms. Platforms position themselves as intermediaries or technology services that optimize the balance between supply and demand. However, in reality, they have considerable power, being able to determine key parameters of labor and employment conditions for formally independent workers. Platform employment is becoming a new reality in the labor market, and requires a deep rethinking of labor market institutions. The notion of “employment via digital platforms” does not have a full-fledged official definition, since there are no regulatory criteria to define it, and the interpretation of some terms differs across countries. DLPs operate across and beyond national borders, giving people more opportunities to provide professional and nonprofessional labor services from all over the world, with the exception of services provided locally. Very often, employees who provide online services operate in low-income countries, and the majority of their customers are located in high-income countries. Thus, the differences in employment and social indicators within the country may decrease, and the exposure of workers to global competition may increase.

Platform employment is in the sphere of interests of foreign researchers [1–7] and major international organizations (Eurofound [8], McKinsey Global Institute [9], OECD [10], BCG [11], European Parliament [12], ILO [13; 14], etc.); as for Russian authors, the number of their publications on the subject is still insignificant [15; 16; 17]. Researchers mainly analyze definitions and terms of platform employment and substantiate its features and properties. The materials of surveys of platform employees conducted by international organizations are of undoubted interest from the point of view of obtaining statistical data, because this new form of employment is not reflected in the statistics of almost any country in the world.

According to expert and statistics estimates [11; 13], platform work is often performed outside of the main work, that is, it is an additional source of income. The legislative gap in relation to platform workers is reflected in the fact that they do not always pay taxes from the income generated by this form of work, which leads to a decrease in tax revenues and the tax base, and also raises the question of the need to adapt the social security and social protection system to the new realities. It is still being discussed whether platform workers belong to the category of payroll employees or whether they should be considered self-employed. In some countries, people whose employment is based on digital platforms have been considered a separate group; but the question of whether new categories of workers should be created remains debatable.

The goal of our research is to identify and study socio-demographic features of platform workers in Russia and the world, compare them and consider the impact of these features on the quality and sustainability of platform workers employment.

The object of the article is digital labor platforms and platform employment. The subject of the article is socio-demographic characteristics of platform workers in Russia and the world, as well as other socio-economic aspects of employment via online platforms.

In the course of the research, we used general scientific methods such as system analysis, comparison, description, generalization, systematization, formalization, etc., and special methods such as analysis of sources, SWOT analysis, expert evaluation method, etc.

Within the framework of the study, we considered platform employment through the prism of sociodemographic and other qualitative and quantitative features that determine quality of employment and are typical of platform workers. Quality of employment is a multidimensional concept with numerous aspects or dimensions that are focused on satisfying human needs in various ways [18]. In particular, international practice distinguishes seven dimensions of quality of employment [19]: 1) safety and ethics of employment; 2) income and benefits of employment; 3) working hours and balancing work and non-working life; 4) security of employment and social protection; 5) social dialogue; 6) skills development and training; 7) workplace relationships and work motivation. Quality of employment cannot be analyzed outside the Decent Work Indicators defined by the International Labour Organization1. In the course of the study, platform employment was analyzed in the context of these indicators and their impact on the degree of its instability.

Research findings

Information base of the research

Estimates of the composition of platform workers in the United States are provided according to The Gig Economy Data Hub2, which is a joint project of the Aspen Institute’s Future of Work Initiative and Cornell University’s ILR School.

Estimates of the composition of platform workers in the EU have been made according to a number of studies:

-

1. The COLLEEM pilot survey, an initial attempt to provide quantitative evidence on platform work. The survey was conducted in 2017 by the Joint Research Centre and covered DLPs in 14 EU member states [20].

-

2. Boston Consulting Group (BBG) 2018 survey [11]. The sample consisted of 11,000 people from 11 countries (1,000 people in each country).

-

3. European Parliament Survey (2017); 50 interviews were conducted in eight European countries, and 1,200 platform workers were interviewed [12].

-

4. Surveys of platform workers of the International Labour Organization (ILO). Two surveys were conducted: in 2015 (1,167 and 677 people) on the Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) and CrowdFlower platforms, and in 2017 (2,350 people) on five platforms: AMT, CrowdFlower, Clickworker, Microworkers and Prolific [13; 14].

Estimates regarding the composition of platform workers in Russia were made based on the following surveys:

-

1. Data from the Workspace portal, which surveyed 3,000 freelancers from its own database in December 2019 – February 20203.

-

2. “Research of Freelancer Service Customers 2020” – a sociological survey conducted by the IT holding TalentTech, the National Research University “Higher School of Economics” and

the Russian freelance exchange FL.ru [21]. The survey was conducted from January to July 2020 and involved 225 people who used the services of freelancers and interacted with them as representatives of organizations or individuals over the past year.

-

3. Data from surveys conducted by the AllRussian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM) on the opinion of Russians about freelancers and their activities (March 2020) 4.

-

4. 16 expert interviews with platform workers (mainly in the field of providing tutoring services) that we conducted in the period from September 1 to December 1, 2020. Among the respondents, ten are women and six are men. The age of the respondents varies from 27 to 64 years, 14 people live in Moscow, one – in Yekaterinburg, one – abroad.

Platform employment coverage

At present it is very difficult to make accurate estimates of the number of platform workers on a global scale due to the ambiguity of the terms and definitions used and the criteria for inclusion of individuals in the category of platform workers. Estimates of the scale of platform work in the world are discussed in detail in [2; 7; 8; 17; 20]. In general, the share of platform workers in the United States and European countries in 2016– 2019 was estimated at 1–5% of total employment. In developing countries, the scale of the platform economy is much larger, especially if we take into account those workers who receive additional, rather than main, income from platform employment [11]. Data on the number of platforms in Europe vary even more: from five (Cyprus) to 300 (France) [8]. The 2020 pandemic has adjusted these numbers. The seventh annual Upwork survey (September 2020), which surveyed more than 6,000 American workers over the age of 18, found that 59 million Americans (36% of the US workforce)

participated in platform work over the past 12 months, i.e. their number increased by two million over 20195. According to the UK freelance platform PeoplePerHour, since the beginning of 2020, the number of its subscribers has grown by 513% in Japan, by 329% in Spain and by 300% in the UK6.

EU estimates show that on average 10% of the adult population has ever used online platforms to provide certain types of labor services (workers with a small share of platform employment) . Less than 8% do this kind of work with some frequency, less than 6% spend a significant amount of time on it (at least 10 hours a week) or earn a significant amount of income (at least 25% of the total) – these are workers with a significant share of platform employment . Main platform workers are those who earn 50% or more of their income via platforms and/or work via platforms more than 20 hours a week. They account for about 2% of the adult population on average. The UK has the highest incidence of platform work. Countries with high relative values of platform employment are Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal and Italy. By contrast, Finland, Sweden, France, Hungary, and Slovakia show very low values compared to other countries [20].

There are no generalized data on the number and composition of Russia’s platform workers, so we can use publicly available information from companies, as well as findings of individual sociological surveys. The scale of platform employment in Russia can be estimated only indirectly, by considering each of the categories that make up the concept of “platform worker”.

In Russia, platform workers belong to several categories (these categories may overlap): self- employed; freelancers; individual entrepreneurs; unregistered workers; employees for whom DLPs provide secondary income; schoolchildren and students (in statistics, they are unoccupied and economically inactive); individuals who work on the basis of a civil law contract, the subject of which is the performance of works and (or) the provision of services, and individuals who work on the basis of an author’s commissioning agreement. In addition, the terms “professional income tax payers”, “selfemployed persons”, “freelancers” and others are used. This creates an issue of uncertainty about their employment status in the labor market.

The term “self-employed” has not yet been defined by law, but the Federal Tax Service clarifies7 that self-employment is a form of employment in which a citizen earns income from their professional activities (for example, provision of services or works, sale of goods they produce) in the implementation of which they are not in an employment relationship with an employer, are not registered as an individual entrepreneur and do not hire employees.

At the moment, there are one million service offers on the well-known digital platform Avito9. The YouDo platform shows offers from more than 1.5 million workers10. The number of Russians officially registered as self-employed in the YouDo service has increased eight-fold since the beginning of 202011. The PROFI.RU platform has more than one million registered specialists in 900 types of services in more than 1,000 cities where the service operates12. Tutor selection service repetitor.ru employs more than 15 thousand tutors, and since March 2020 it has been working with customers around the world13. Obviously, many platform workers register on several platforms at once, which makes it difficult to assess the scale of this type of employment. According to a VTsIOM survey14, every tenth Russian (11%) can call themselves a freelancer or self-employed.

As for the company Uber, it employs more than 22 thousand people in more than 700 cities15. In Russia, Uber is currently present in 17 cities, including Yekaterinburg, Kazan, Novosibirsk, and Voronezh16. The number of drivers connected to the platform in Russia is estimated in the tens of thousands, but there are no exact estimates in the public domain.

Socio-demographic characteristics of platform workers

Platform workers in the United States17, Europe [20], and Russia18 are on average 10 years younger than traditional workers. If the age distribution of ordinary workers is normal, then for platform workers it is biased toward the young; moreover, the age decreases with the increase in the intensity of platform employment.

According to the ILO study [13], the average age of platform workers was 33.2 years in 2017 and 34.7 years in 2015. It was different for different platforms. Indian workers were on average younger (31.8 years old) than American workers (35.5 years old). The majority of platform workers are between 25 and 40 years old; 10% are over 50, with the oldest respondents being 83 and 71 in 2015 and 2017, respectively.

According to the estimates of the Eurofound [8], the proportion of people under 35 years of age among European platform workers is significantly higher than among traditional workers. On average, only 5% of platform workers are 56–65 years old (in Austria – 13%, in Estonia – 6%, in the Czech Republic – 4% are 45 to 59 years old and 1% are over 60).

As for gender distribution, as the intensity of platform work increases, the proportion of women from the EU who engage in platform work gradually decreases [20]. In particular, women make up 47.5% of offline employees, 40.2% of insignificant platform workers, 31.2% of significant but not main platform workers, and only 26.3% of main and very significant platform workers. The representation of women among platform workers varies greatly across countries. If we look at gender and age in the aggregate, we will notice an even more dramatic division, the proportion of older women gradually decreases as the intensity of platform work increases: 34.2% of those engaged in offline work are women aged 35 and older. This share is almost halved (to 18.7%) among those who provide services from time to time via online platforms, 15.2% of respondents working via platform, and only 10.6% among those for whom platform work is the main source of income. On the contrary, the share of young men increases significantly with an increase in the intensity of platform work: from 12.7% among offline workers to 37.8% among those who receive their main income via platform.

According to earlier (2015 and 2017) data from the ILO [13], women to men ratio for platform workers is one to three. In developing countries, the gender distribution is particularly uneven: only one in five platform workers is a woman.

Data from the Eurofound [8] also show that men are more likely to perform platform work than women. In Austria, men make up 57% of platform workers, in the Netherlands – 60%. A study of five Eastern European countries found that 58% of platform workers were men. In the Czech Republic, 8% of men and 5% of women have experience working on the platform. In Estonia, about 26% of men, compared to 13% of women, have done work via platform at least once in the past.

In the United States, the distribution of workforce by gender depends on the type of survey: men and women participate in different types of platform work19. Men are significantly more likely than women to be involved in online work via platforms and are employed full-time. Women are more likely to receive additional income via platforms and work part-time.

This gender imbalance is based on discriminatory grounds. There are studies, for example [2], showing that women suffer statistical discrimination: they are less likely to be hired for jobs that are predominantly male (such as programming), and are more likely to be hired for jobs that are predominantly female (such as customer service).

According to the Russian survey20, among freelancers, the share of women is 46.8%, men – 53.2%, i.e. they are approximately equal. Our own expert interviews also show the gender balance among tutors, but these data are unrepresentative and cannot be extended to the entire population of workers.

The employment status of platform workers is one of the most pressing issues in terms of the quality and instability of employment. Estimates from the COLLEEM survey reveal that when asked about their current employment situation, 68.1% of the platform workers claimed to be an employee (68.1%) and 7.6% – self-employed. These answers can be explained in different ways. A first possibility is that platform workers also have a regular job as employees or self-employed and are therefore covered by standard employment legislation. A second possibility is that platform workers are not really sure of their employment status and may see themselves as employees, only because they provide a certain type of service with regularity through the same platform. This is a contradiction, because in most cases the providers of labor services via platforms are formally independent contractors rather than employees. The labor market status of platform workers remains unclear, even to themselves.

According to the freelancers survey21, half of respondents in Russia at the end of February 2020 worked off the books, 16.6% were self-employed, 9.8% worked under a civil law contract, and 23.7% were individual entrepreneurs. At the same time, freelancing is the only source of income for 2/3 of respondents, and a third of respondents have a steady job and use freelancing to earn additional income. Only 10% of organizations conclude a formal contract with freelancers, one third rely on the tools of remote work exchanges, such as secure transactions, etc., and more than half of customers do not formalize their labor relations with freelancers in any way [21].

Platform workers are on average more educated than the comparable general population. Among main platform workers, 55% have a high education , compared to 35.3% for the average worker in the EU [20]. According to [13], platform workers are well educated: 37% had a bachelor’s degree, 20% – a master’s degree. Among the degree holders, 57% had a major in science and technology (12% – in natural sciences and medicine, 23% – in engineering, and 22% – in information technology), 25% specialized in economics, finance and accounting. Data of the survey [11] also show a high level of education of platform workers.

To be able to provide services via platform one needs to be a savvy internet user, and internet use usually correlated with higher education. In addition, many types of work performed via online platforms require a higher than average level of skills, hence platforms could be a tool to improve the allocation of highly skilled workers to highly skilled tasks. This may also be related to the fact that some young and educated workers have difficulties in finding regular employment and resort to platform work to make ends meet.

In the U.S., according to most surveys, the platform workforce as a whole is only slightly more educated than the traditional workforce. Freelancers are more likely than traditional workers to have an academic degree. Conversely, temporary workers and on-call workers often do not even have a high school diploma22. In the Russian sample, 35.4% have a specialized higher education23.

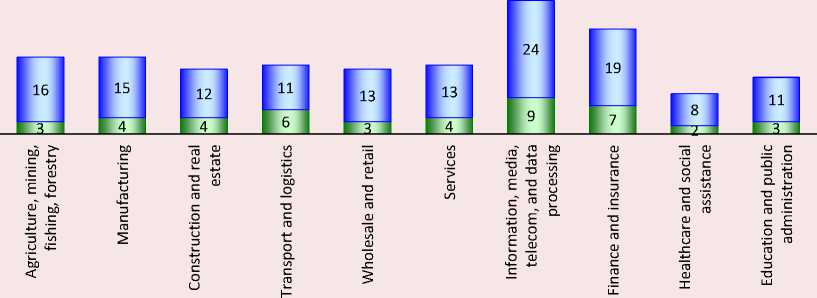

Platform employment is represented in almost all industries and it is an additional rather than the main income source for the majority of workers. Figure 1 shows the distribution of platform workers by industry, according to the study by Boston Consulting Group (BSG).

Figure 1 shows that platform work is more often represented in IT, media, telecom, data processing,

Figure 1. Platform workers, broken down by industry, BCG, 2018, % of respondents

□ Platform work is a primary source of income □ Platform work is a secondary source of income

Source: Wallenstein J., de Chalendar A., Reeves M., Bailey A. The New Freelancers: Tapping Talent in the Gig Economy. BCG Henderson Institute, 2019.

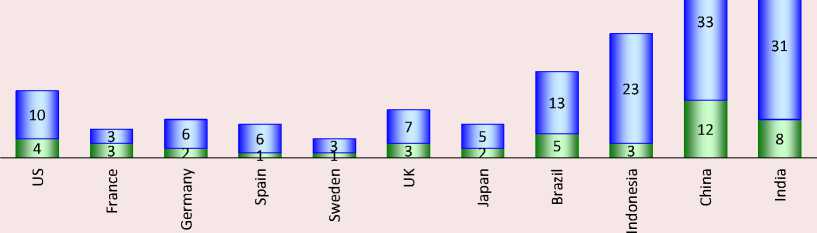

Figure 2. Distribution of platform workers broken down by country, BCG, 2018, % of respondents

□ Platform work as primary income □ Platform work as secondary income

Source: Wallenstein J., de Chalendar A., Reeves M., Bailey A. The New Freelancers: Tapping Talent in the Gig Economy. BCG Henderson Institute, 2019.

and in finance and insurance. In all the surveyed activities, platform work was mainly a secondary rather than primary source of income (Fig. 2) .

On average, half of the overall European platform workers perform both digital and on-location services. This suggests that many workers perform more than one type of task via platform.

Companies from various fields actively cooperate with Russian freelancers [21]. Typical customers are organizations engaged in software development, development, support and promotion of websites, working in the field of design, marketing, PR, advertising; as well as trade and industrial organizations (each of these areas accounts for 10–13% of respondents). For 23% of customers, hiring freelancers is an integral part of the business model, and 19% point out that freelancers play an important role in the organization’s activities.

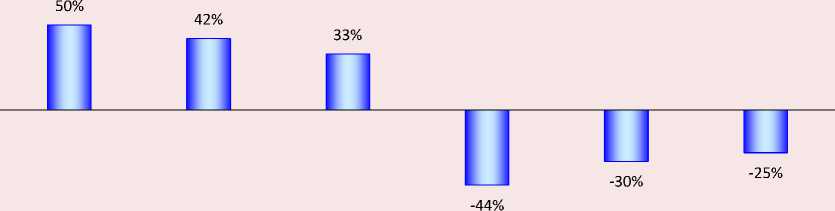

During the COVID-19 pandemic, different sectors of the Russian platform economy are experiencing divergent trends. Figure 3 shows the dynamics of demand for and supply of services in the areas of platform work.

Figure 3. Dynamics of platform work in Russia during the pandemic (supply and demand), broken down by industry

Demand dynamics

Delivery Hairdressers, Tutors and teachers Photographers and Cleaners and Maintenance and psychologists, videographers household staff construction fitness instructors, specialists nail artists

Supply dynamics

|

74% |

74% |

66% 63% 62% |

||||||||

|

U и -24% -33% Couriers Web developers Working with Computer repair Tutors and Event promotion Major repair text, audio teachers services transcription services, advertising and In t ernet promotion |

||||||||||

Source: The most popular professions during the lockdown have been named. Available at: obshchestvo/19052020/118331

According to the COLLEEM survey, for most workers, the conditions of platform work are flexible and safe: platform workers decide for themselves when and how many hours to work and which tasks to perform. Nevertheless, there is a significant proportion of platform workers who consider their work stressful and routine. While all three categories of those working via platform are characterized by similar values in terms of flexibility and security, poor conditions tend to increase as the intensity of platform work increases. More than half of the significant and main platform workers often consider their work stressful and routine, but they are more likely to say that their work via platform is paid fairly.

Respondents who predominantly provided professional services would in general be better paid but also face stressful situations more frequently. Non-professional platform work is associated with more routine tasks and fewer learning opportunities, but also with less stressful situations. On-location platform work tends to give the worker less choice over the tasks to be carried out and less learning, but also a lower level of routine.

Working hours is one of the core dimensions of working conditions (a component of quality of employment). In the COLLEEM survey, platform workers were asked how many hours they work in general and how many specifically on platforms. For all platform workers, the total number of working hours (including platform and non-platform work) is surprisingly small: almost one third of them work less than 10 hours a week, more than 50% work less than 30 hours a week, and only 15% work 40 hours a week. If we look at the hours of work in platforms, the values are even smaller: 42% of platform workers work via platforms less than 10 hours a week, and three quarters – less than 30 hours a week. However, there are significant differences by categories of platform workers: non-significant workers, as a rule, have very short work schedules, the hours of main and very significant platform workers are much closer to those of a regular worker. Almost 24% of platform workers (online and offline) work 40 hours a week, another 24% – between 30 and 39 hours a week, and only 5% work less than 10 hours a week, while 12% of all main platform workers have very long schedules – more than 60 hours a week.

According to [13], many platform workers work atypical hours: 36% regularly worked seven days per week; 43% reported working during the night and 68% reported working during the evening (6 p.m. to 10 p.m.), either in response to task availability (and differences in time zones) or because of other commitments. Many women combined work with childcare responsibilities (one out of five female workers in the sample had small children 0 to 5 years old). Nonetheless, these women spent 20 hours per week on the platform, just five hours fewer than the sample as a whole; many worked during the evenings and at night.

The situation is somewhat different for Russian freelancers24: 30.5% work less than 6 hours a day, 28.7% – more than 8 hours a day, and 4.1% – more than 12 hours a day. At the same time, 35.7% work several times a month on Saturdays and Sundays, while only 6.7% have their days off at weekends.

The opinion of Russians about the average number of working hours per week for platform workers (self-employed or freelancers) in comparison with regular employees is roughly consistent with reality25: a quarter of respondents believe that the self-employed work more than full-time employees, another quarter of respondents think the amount of working hours in two groups is the same, still another quarter find it difficult to answer (each quarter of respondents make up 28%, respectively). The fact that the self-employed work more is pointed out more likely by men (31%) and by Russians aged 45–59 (32%), as well as by those who have a positive attitude toward freelancers (36%). Representatives of the younger generation aged 18–24 and 25–34 are more likely to believe that the average number of working hours for the self-employed is equal to that for regular employees (41 and 39%, respectively). Only 16% of Russians assume that freelancers work less. This opinion is typical of young people (28%).

The issue concerning the number of hours of platform work in the context of quality of employment has two implications. If platform workers work less than the standard 40 hours a week, because it suits their lifestyle, helps them balance work and family commitments, or because they work so efficiently that they complete tasks faster than their customers expect, this positively characterizes the quality of their employment. If their working hours reduce due to a lack of demand for their work or the inability to find work via platforms, then this indicates the presence of risks related to platform work. The ILO research [14] shows that the demand for such work often exceeds the supply: 89% of the surveyed crowdworkers report that they would like to perform a larger amount of such work than at present, although 44% of them have access to more than one platform; 49% believe that “the amount of work is insufficient”, 22% say that the wage is not high enough.

Thus, we can conclude that the conditions of platform work are more polarized than those of regular workers.

In the U.S., more than two-thirds of platform workers report being satisfied with their work arrangements26. Just like in the EU, they appreciate the control this work allows them over their time and the flexibility of scheduling. Platform work income smooths unstable earnings from a traditional job, helps deal with financial hardships, meet basic needs and pay the bills; some workers use their platform earnings for traveling or other discretionary expenses.

As for the motives or reasons for platform work, the most significant for European workers [13; 20] are flexibility on where and when to work, possibility to balance work and family commitments and being one’s own boss, followed by characteristics of the work itself (interesting work, attractive pay). The less frequently mentioned motivations include difficulties associated with finding a regular job, health issues, desire to work part-time. For women, the main reason to work remotely is the need to care for their children. In the ILO survey [13], 10% of respondents indicated health issues (platforms give them the opportunity to continue working and earn income).

For American workers, an important motivation is the low barrier to access digital labor platforms. Some types of platform work are accessible for workers who may otherwise struggle to enter the labor market, including immigrant and formerly incarcerated populations27.

Half of the surveyed Russian freelancers28 named the desire to work on a flexible schedule as the main motivation; 35.9% do not want to work in the office, and 30.3% want to have more time for themselves. More than a quarter of the surveyed freelancers (26.8%) are introverts, they are more comfortable working remotely. Other reasons for platform work are related to professional development: 12.5% of respondents are bored with working for the same employer, and 11.9% wanted to achieve professional growth. The main advantages of freelancing, according to the freelancers themselves, are the ability to work remotely from anywhere (78.5%) and flexible working hours (74.8%); 44.6% are satisfied with the fact that they work only for themselves and create their own income; 39.3% have more time for themselves and their families thanks to freelancing.

Professional development and career development opportunities are important indicators for assessing the quality of platform work at the current moment and the quality of employment of the individual throughout their working life. One of the signs of platform work, recognized by international organizations and researchers, is the fragmentation of work [8], that is, the division of work processes into specific simple routine tasks (micro-tasks), which, when being performed, make it difficult for workers to improve their skills. Career promotion and professional growth can be achieved only by highly qualified freelancers who provide their services (web development, creative texts and translations, graphic design, accounting and legal advice) via specialized platforms, which often cooperate with international corporations and well-known companies (platform outsourcing). For example, AppJobber lists companies like Nestle, Sony and Telefonica among its clients. Clickworker has facilitated the provision of various types of labor outsourcing services for Deutsche Telekom, Honda, and Sharewise. The freelancing platforms Upwork, Peopleperhour, 99Designs, iWriter are being used by over five million businesses, including Accenture, AirBnB, and UCLA [7].

Negative aspects of platform work for both European and American workers are as follows: unpredictability of income, which leads to psychological stress and economic issues; lack of access to benefits, including health insurance and pension plans; and insecurity in work relations with customers. ILO survey findings [14] show that workers with more than six months’ experience face a substantial amount of rejections: 43% have had at least 5% of their work rejected, and 32% have had at least 10% of their work rejected. A number of platforms have rejection clauses (e.g. AMT, Clickworker, Microworkers) which allow the clients/requesters to reject received work as unsatisfactory with little or no justification.

The main disadvantages of freelancing, according to the freelancers themselves, are unstable income (65.7%), sedentary lifestyle (54.5%), tough competition in the market (41.9%), lack of communication (32.8%), poor self-discipline (30.2%), and frequent overwork (25.8%).

In the course of the interviews, respondents noted such negative aspects as the “invasion” of work in their personal lives and, in fact, the round-the-clock stay on the aggregator’s website (responding to customer requests, finding new students, sending reports and reading reviews about their work), the costs of organizing a remote workplace (Internet, computer, and software), social isolation and the lack of even a semblance of a team of labor colleagues.

To assess the quality of this type of employment, we find it important to consider whether the advantages of platform work compensate for its disadvantages. In the framework of expert interviews, respondents (tutors) said that, despite all the difficulties, platform work has become the best solution for combining paid activities, professional development, and fulfilling family obligations. For half of the respondents, platform work was their main job (women with small children, women and men of retirement age), and the other half said it was their additional job (middle-aged people).

According to the European survey [20], there are many more low-income people in the sample of platform workers in comparison with the general population, but the more hours a worker devotes to this activity, the lower the probability of receiving a low income.

A number of studies [13; 14] show that crowdworkers receive low pay by the standards of industrialized countries. Earnings varied depending on the platform and the country of the worker: CrowdFlower and Microworkers are the lowest-paying platforms (averaging 2 USD per hour). Prolific Academic and Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) remain the highest-paying platforms, with workers averaging 4.4 and 3.6 USD per hour, respectively; 75% of U.S. crowdworkers earned less than the federal hourly minimum wage. The low level of pay may be partially attributed to the significant amount of time that workers spend on unpaid work (looking for tasks, taking qualification tests, and researching clients), as well as the small number of hours worked, as we have already mentioned above.

As for Russian freelancers, 72.3% “never run out of money”, but only 34.5% are likely to call their income stable. At the same time, the income of 69.9% of freelancers equals or exceeds the average pay in their region, 71.3% of freelancers want to earn more; 71.4% of respondents under 21 years of age and 73.38% of respondents aged over 50 receive up to 40,000 rubles a month, 68.8% of respondents aged from 30 to 40 earn up to 80,000 rubles a month. There is a noticeable difference in the earnings of freelancers without legal status and those registered as individual entrepreneurs: 41.5% of individual entrepreneurs and only 10.3% of freelancers without legal status earn more than 100,000 rubles a month. This indicates a certain degree of polarization in the income distribution among different categories of platform workers.

Interesting results are obtained when comparing these data with Russians’ opinion about the earnings of freelancers29: 31% of Russians believe that freelancers earn more than regular employees; 26% say their incomes are equal; 12% say that freelancers earn less.

We discussed social security of platform workers in more detail in [16]. Since most digital labor

-

29 Russians came to love freelancing. Available at: https:// (accessed: March 15, 2021).

platforms classify workers as independent contractors, platform workers are solely responsible for paying social security contributions; moreover, they are excluded from other forms of social protection. According to all the analyzed studies, the social protection coverage of platform workers is very low: according to ILO surveys [13], only six out of ten respondents were covered by health insurance in 2017, and only 35% had a pension plan. In most cases, this coverage stemmed from the respondents’ main job or through family members, or was funded by the state as part of universal benefits. About 16% of the workers for whom platform work is the main source of income were covered by a retirement plan, compared to 44% of those for whom platform work was not the main source of income. According to [14], In the case of the 56% of workers who state that crowdworking is their main job, only 55% of these report that they have access to health coverage, and only 24% make contributions to their health insurance. The proportions are even lower with respect to pensions: only 25% of workers have access to a pension scheme, and only 15% make contributions to a pension. Workers from Western Europe have better coverage than those from Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Platform workers have very limited opportunities for engaging in social dialogue30 that guides the participation of workers, employers, and governments in employment decision-making and includes negotiations, consultations, and information exchange among representatives of these groups regarding common interests in socioeconomic and labor policies. Many platforms specifically prohibit workers from joining any

-

30 International Labour Conference, 102nd Session, 2013. Report VI: Social dialogue. Recurrent discussion under the ILO Declaration on Social Justice for a Fair Globalization. International Labour Office. Geneva. Available at: https:// www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/ documents/meetingdocument/wcms_210128.pdf (accessed: March 15, 2021).

trade unions and conducting collective bargaining. Europe takes active steps to address this issue [16]. The solution for Russian workers could be to establish a “digital trade union” [22] in the form of a set of services available to every worker, regardless of the form of employment.

Conclusions

Platform workers are different from regular employees. However, just as there is no “average” traditional worker, we cannot derive a formula for an “average” platform worker. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify signs of the quality of employment of platform workers that affect the stability of employment.

The results of the comparative study suggest that platform workers in Russia and other countries have many similar socio-demographic features. In general, it can be argued that platform workers are younger and more educated. There are more men than women among platform workers. There are significant differences among workers, depending on whether they perform digital or on-location services. The quality of employment of online workers is generally better. Perhaps this is due to the fact that they perform more skilled work that requires a higher level of education and provides an opportunity for professional growth.

The advantages and disadvantages of platform work are distributed unevenly. The work that some workers perform so as to smooth out or supplement their income is a source of high financial instability for others. What brings flexibility and freedom to some (mothers with young children, the disabled, pensioners, schoolchildren and students living in remote areas, etc.), becomes a cause of instability and insecurity for others (taxi drivers, microtask workers, home staff, construction workers). The needs of a highly qualified freelancer are fundamentally different from those of a fulltime employee. Researchers should continue to study features of platform workers to get a better understanding of the range of needs of this group of workers.

The architecture and model of digital labor platforms can involve the exchange of highly substitutable or standardized work or become a channel for exploitation of workers (Uber, CrowdFlower, AMT), while others provide a space for workers to develop more specialized services and build a network of professionals (Toptal, 99Designs, iWriter); as a result, the architecture of the platform has important implications for the workers’ autonomy, as well as their working conditions and earnings.

As for the employment status of platform workers, we consider it impractical to introduce a separate category of those “employed on digital labor platforms”, since they can be classified either as economically dependent performers and contractors, or as self-employed. In Russian legislation, it is necessary to determine the specifics of the legal status of the self-employed in general, to develop rules for economically dependent performers and contractors (dependent selfemployed), and to create provisions that reflect the specifics of employment on digital labor platforms.

The new form of employment we have considered requires new solutions in the field of remuneration, preservation and documentation of workers’ experience, professional development and retraining, and protection of their labor rights [16]. From the point of view of social protection, it may be necessary to introduce insurance models that are not based on employment status.

Conducting large-scale nationwide surveys and introducing platform employment indicators in the surveys of the Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat), Federal Service for Labor and Employment (Rostrud) and other agencies can become important steps in studying the quality of employment of Russian platform workers.

Список литературы Socio-demographic characteristics and quality of employment of platform workers in Russia and the world

- De Stefano V. The rise of the “just-in-time workforce”: On-demand work, crowdwork and labour protection in the “gig-economy”. In: Conditions of Work and Employment Series, 2016, no. 71.

- Bogliacino F., Codagnone C., Cirillo V., Guarascio, D. Quantity and quality of work in the platform economy. GLO Discussion Paper, 2019, no. 420. Global Labor Organization (GLO), Essen. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/205800 (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Choudary S.P. The architecture of digital labour platforms: Policy recommendations on platform design for worker well-being. In: ILO Future of Work Working Paper Series, 2018. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/ wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---cabinet/documents/ publication/wcms_630603.pdf (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Codagnone C., Karatzogianni A., Matthews J. Platform Economics: Rhetoric and Reality in the «Sharing Economy». Emerald Publishing Limited, 2018. Pр. 169–199. Available at: https:// doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78743-809-520181009 (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- De Stefano V., Aloisi A. European Legal Framework for Digital Labour Platforms, European Commission, Luxembourg, 2018. DOI: 10.2760/78590 (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Schwellnus C., Geva A., Pak M., Veiel R. Gig economy platforms: Boon or bane? Organisation for economic co-operation and development. Economics Department Working Papers, 2019, no. 1550 (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Engels S., Sherwood M. What if We All Worked Gigs in the Cloud? The Economic Relevance of Digital Labour Platforms. European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/ economic-and-financial-affairs-publications_en. DOI:10.2765/608676 (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Mandl I. New Forms of Employment: 2020 Update. New forms of employment series. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg, 2020.

- Independent Work: Choice, Necessity and the Gig Economy. McKinsey Global Institute, 2016.

- An Introduction to Online Platforms and Their Role in the Digital Transformation. OECD Publishing. Paris, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/53e5f593-en

- Wallenstein J., de Chalendar A., Reeves M., Bailey A. The New Freelancers: Tapping Talent in the Gig Economy. BCG Henderson Institute, 2019.

- The Social Protection of Workers in the Platform Economy. Study for the EMPL Committee. IP/A/EMPL/2016-

- European Parliament, 2017. Available at: http:// www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Berg J., Furrer M., Harmon E., Rani U., Silberman M. Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World. Geneva, 2018.

- Job Quality in the Platform Economy. Geneva, ILO, 2018. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/futureof-work/publications/issue-briefs/WCMS_618382/lang--en/index.htm (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Geliskhanov I.Z., Yudina T.N., Babkin A.V. Digital platforms in economics: Essence, models, development trends. Nauchno-tekhnicheskie vedomosti SPbGPU. Ekonomicheskie nauki=St. Petersburg State Polytechnical University Journal. Economics, 2018, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 22–36. DOI: 10.18721/JE.11602 (in Russian).

- Chernykh E.A. The quality of platform employment: Unstable (precarious) forms, regulatory practices, challenges for Russia. Uroven’ zhizni naseleniya regionov Rossii=Living Standards of the Population in the Regions of Russia, 2020, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 82–97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.19181/lsprr.2020.16.3.7 (in Russian).

- Bobkov V.N., Chernykh E.A. Platform employment – the scale and evidence of instability. Mir novoi ekonomiki=The World of the New Economy, 2020, no. 14 (2), pp. 6–15. DOI: 10.26794/2220-6469-2020-14-2-6-15 (in Russian).

- Bobkov V.N. et al. Kachestvo i uroven’ zhizni naseleniya v novoi Rossii (1991–2005 gg.) [Quality and Living Standards of the Population in the New Russia (1991-2005)]. Moscow: VTsUZh, 2007.

- Measuring Quality of Employment. Country Pilot Reports. Geneva, 2010.

- Pesole Annarosa et al. Platform Workers in Europe. Evidence from the COLLEEM Survey. JRC Science for Policy Report. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientificand-technical-research-reports/platform-workers-europe-evidence-colleem-survey (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Issledovanie zakazchikov uslug frilanserov 2020. IT-kholding TalentTech, Vysshaya shkola ekonomiki, birzha frilansa FL.ru [Research of customers for freelance services 2020. IT holding TalentTech, Higher School of Economics, freelance exchange platform FL.ru]. Available at: https://freelance.hb.bizmrg.com/freelance_customer_research_2020.pdf (accessed: 26.12.2020).

- Loktyukhina N.V., Chernykh E.A. Dynamics and Quality of platform employment in the era of coronavirus: Challenges for Russia. Uroven’ zhizni naseleniya regionov Rossii=Living Standards of the Population in the Regions of Russia, 2020, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 80–95. DOI: 10.19181/lsprr.2020.16.4.7 (in Russian).