Sorbic and benzoic acids affect adrenal morphology under chronic stress in male rats

Автор: Ryabova Yu. V., Gizatullina A. A., Khmel A. O., Mukhammadiyeva G. F., Smolyankin D. A., Repina E. F., Kurilov M. V., Karimov D. O.

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Background: Chronic stress significantly impacts endocrine function, especially in the adrenal glands, which produce hormones essential for stress adaptation. Food preservatives such as sorbic and benzoic acids are widely used in the food industry, yet their long-term effects on the endocrine system under stressful conditions remain poorly understood. This study aimed to determine whether combined chronic stress and high-dose preservatives induce more pronounced structural changes in the adrenal glands of male rats than either factor alone.

Chronic stress, food preservatives, adrenal glands, morphological changes, rats

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143184734

IDR: 143184734

Текст научной статьи Sorbic and benzoic acids affect adrenal morphology under chronic stress in male rats

In modern society, chronic stress has become a pervasive component of daily life, exerting effects that range from disruptions in homeostasis to potentially lifethreatening conditions (Yaribeygi et al., 2017). A critical mediator of the stress response is cortisol, a glucocorticoid hormone produced by the adrenal glands, which plays a pivotal role in various physiological processes. Elevated cortisol levels can induce DNA damage via reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, leading to base modifications and strand breaks (Flaherty et al., 2017). At the molecular level, cortisol also contributes to insulin resistance in adipose tissue, liver, and muscle (Beaupere et al., 2021). Prolonged cortisol elevation due to chronic stress has been implicated in metabolic disorders such as obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammatory bowel diseases (Hewagalamulage et al., 2016), and may promote tumorigenesis and cardiovascular events (Knezevic et al., 2023).

Concurrently, continuous exposure to stress is now recognized as a key contributor to endocrine dysfunctions, including impaired adrenal gland function (Stagl et al. , 2018; Borrow et al. , 2019; Berger et al. , 2019).The adrenal glands themselves are central to the organism’s adaptation to stress by regulating the synthesis of corticosteroids and catecholamines (Berger et al. , 2019). Prolonged stress can lead to both morphological and functional alterations in the adrenal cortex and medulla, ultimately disrupting homeostasis and diminishing the body’s overall resilience (Lee et al., 2015). Recent attention has also focused on the health implications of food additives and preservatives (Sambu et al., 2022; Hrncir et al., 2024; Emami et al., 2024). Sorbic and benzoic acids are widely used in the food industry; however, their long-term endocrine effects– particularly under chronic stress condition–remain insufficiently examined.

Investigating the combined impact of chronic stress and these commonly employed preservatives on adrenal morphology is thus of both scientific and practical importance. Such research enhances our understanding of potential risks associated with sustained endocrine dysfunction, sheds light on the mechanisms governing adrenal adaptation to adverse factors, and informs preventive strategies aimed at mitigating the long-term consequences of stress and dietary additives. We hypothesized that simultaneous exposure to sorbic and benzoic acids under chronic stress would induce more pronounced morphological alterations in the adrenal glands than either factor alone. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the toxic effects of sorbic and benzoic acids on the adrenal morphology of male rats subjected to chronic stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical Approval. Experimental modeling of chemical exposure under chronic stress conditions was approved by the Institutional Bioethics Committee (Protocol No. 01-02, dated February 8, 2024). All procedures for animal housing, feeding, care, and euthanasia were carried out in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation on the treatment of laboratory animals, as well as the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS No. 123) and Directive 2010/63/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Animal Model and Group Allocation. The study design followed the ARRIVE guidelines to ensure high-quality reporting of animal experiments. Outbred male white rats (body weight 190–210 g, age 10–12 weeks at the start) were randomly assigned to four groups (n=6 per group):

-

• Control Group: Received an equivalent volume of distilled water without additives.

-

• Stress Group: Exposed to stressors and also received distilled water in the same daily volume.

-

• Preservatives Group: Received daily aqueous solutions of sorbic acid (500 mg/kg body weight, 100 mg/mL) and benzoic acid (100 mg/kg body weight, 20 mg/mL), administered at the same time each day.

-

• Stress + Preservatives Group: Exposed to the same preservative regimen as the Preservatives Group, in addition to the chronic stress protocol.

The doses of sorbic and benzoic acids were set to ten times the average daily intake for an adult human, based on the list of food products approved by R2.1.10.3968-23 (Moscow, 2023) and TR TS 029/2012 (adopted by the Eurasian Economic Commission Council, No. 58 dated July 20, 2012). It is important to note that this study did not aim to replicate real-world consumption patterns of sorbic or benzoic acids for any specific population group; rather, it sought to identify potential toxic effects on the adrenal glands under chronic stress conditions at high-dose exposures to these widely used preservatives. In summary, the study design evaluated (1) the impact of stress, (2) the impact of preservatives, and (3) their combined effects on the morphological parameters of the adrenal glands. An overview of the experimental design is presented in Figure 1.

Chronic Stress Protocol. Chronic stress was induced following the method described by Matisz et al. (2021). Animals were subjected to mild, unpredictable stressors on a daily basis, comprising 2–3 randomly selected factors such as social isolation, immobilization, exposure to noise, continuous lighting during the dark phase, and restricted access to food and water for a limited period. Each combination of stressors was applied at random times over the course of a day, ensuring that the same stress factor was not repeated twice within a single day.

Evidence of chronic stress in the animals was confirmed by several behavioral and physiological signs, including reduced weight gain compared to the Control group, alterations in locomotor activity, and a tendency toward diminished exploratory behavior Gizatullina et al., 2024 a; Gizatullina et al., 2024 b), consistent with stress-induced changes described in related studies (Alexa et al., 2023).

Measurements of biochemical stress markers (e.g., corticosterone or cortisol) were deliberately omitted due to the substantial influence of circadian rhythms and procedural interventions (blood sampling) on hormone levels, which reduces the specificity of such assessments (Kim et al., 2018; Perhonen et al., 1995). Moreover, while cortisol is the principal stress hormone in humans, corticosterone serves this role in rats, complicating direct comparisons of these results with clinical data focused on human physiology (Joëls et al., 2019).

Euthanasia and Tissue Collection. After 4 weeks of exposure, animals were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation followed by decapitation. Body mass was recorded prior to euthanasia. Both the right and left adrenal glands were dissected, inspected, weighed, and the relative organ mass was calculated in relation to total body weight for each animal.

Histological Processing and Morphological Analysis. Adrenal gland tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Standard histological procedures were followed, including graded alcohol dehydration, xylene clearance, and embedding in paraffin to form tissue blocks. From each animal, two paraffin blocks were prepared. Sections 5–7 µm thick were cut on a Leica RM 2125 RTS rotary microtome (Leica Biosystems, Germany), stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined under a Celena X imaging system (Logos Biosystems, South Korea) at magnifications of ×200 and ×400. Morphological evaluation was performed by experts blinded to group allocation.

Morphometric analysis was conducted using the open-source software uPath-0.5.1 (The ueen’s University of Belfast, United Kingdom). In the zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis of each adrenal gland section, the nuclear area and perimeter were measured in 50 cells (one representative section per animal). Additionally, cell density per field of view was calculated across 50 fields (one section per animal).

Following literature-based recommendations, we selected these parameters for their diagnostic relevance. Nuclear area is widely assessed as an indicator of changes in metabolic activity and functional status (Rogovskaya et al., 2008; Alyabyev et al., 2008; Belyaev et al., 2017). Nuclear perimeter can reflect chromatin restructuring or membrane alterations associated with apoptosis, regeneration, or stress-induced damage (Areshidze, 2022). Cell density per field of view, although nonspecific, can indicate atrophic or hyperplastic processes in the tissue (Ilyasov, Umarkulova, 2024), making it useful for comparative rather than absolute quantification.

Statistical Analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM, USA). Normality was assessed via the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For normally distributed data, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s and Tamhane’s post-hoc tests were applied. Data are expressed as mean and standard error (SE). For non-normal distributions, the Kruskal–Wallis test (for comparisons of three or more groups) and the Mann–Whitney test (for comparisons between two groups) were used. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Macroscopic evaluation showed that the adrenal glands in both control and experimental groups were located at the cranial poles of the kidneys within the perirenal adipose tissue, exhibiting a normal size of approximately 5 mm, a uniform yellowish color, a beanlike shape, and a firm consistency. There were no significant differences in adrenal mass or the relative adrenal-to-body weight ratio among groups: Control (0.18 ± 0.01 g), Stress (0.20 ± 0.01 g), Preservatives (0.18 ± 0.01 g), and Stress + Preservatives (0.20 ± 0.01 g).

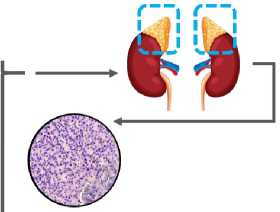

Representative histological overviews of the adrenal cortex in the control and experimental groups are presented in Figure 2. In the control group, the cortex showed a well-defined zonal arrangement, with orderly cellular organization and distinct fasciculate and reticular zones distinguishable by differences in cell density and morphology. The fasciculate zone consisted of large cells arranged in parallel cords and showing pronounced cytoplasmic vacuolization, indicative of high lipid content. In the reticular zone, smaller cells with basophilic cytoplasm formed a characteristic network. No signs of inflammation, edema, or other pathological changes were observed.

In the Stress group, the fasciculate zone exhibited increased vacuolization, cytoplasmic clearing, and widening of the intercellular spaces, most notably in the medullary region. The reticular zone maintained a relatively orderly cellular architecture.

Animals receiving only preservatives displayed a generally preserved architecture of the cortical layers, with intact zonal differentiation. However, the medullary region showed signs of functional alterations, including vacuolation and partial disruption of cell architecture.

The most pronounced histological changes were found in the Stress + Preservatives group, where marked expansion of intercellular spaces was detected in the adrenal cortex, consistent with edema. The structure of the glomerulosa zone remained comparatively intact.

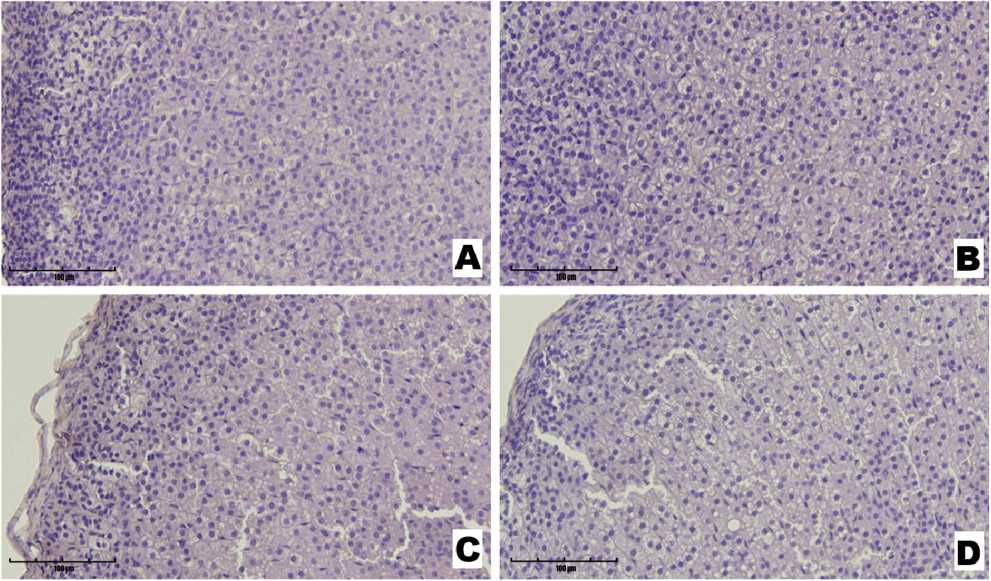

Morphometric assessment revealed that, in the glomerulosa zone, the nuclear area of adrenocortical cells in the Control group was 9.77 ± 0.33 µm², not differing from that in the Stress + Preservatives group (9.82 ± 0.22 µm², p = 0.999). By contrast, rats subjected to either Stress (11.31 ± 0.29 µm²) or Preservatives alone (13.85 ± 0.24 µm²) displayed significantly larger nuclear areas compared to Control (p = 0.001 for both). Additional comparisons indicated a statistically significant difference between the Stress and Preservatives groups (p = 0.001). In the Stress + Preservatives group, nuclear area was significantly lower than in the Preservatives group (p = 0.001). Nuclear perimeter exhibited a different pattern: it decreased in both the Stress group (12.36 ± 0.16 µm vs. 13.33 ± 0.27 µm in Control, p = 0.001) and the Stress + Preservatives group (11.46 ± 0.13 µm, p = 0.001), but remained unchanged in the Preservatives group (13.43 ± 0.12 µm, p = 0.083). Significant differences were also noted between Stress vs. Preservatives (p = 0.001) and Preservatives vs. Stress + Preservatives (p = 0.001). Cell density (cells per field of view) in the glomerulosa zone did not differ statistically among groups, with values of 105.33 ± 5.36 (Control), 112.33 ± 3.76 (Stress), 100.00 ± 6.25 (Preservatives), and 120.00 ± 6.66 (Stress + Preservatives). Representative micrographs of the glomerulosa zone and corresponding graphical data are shown in Figure 3.

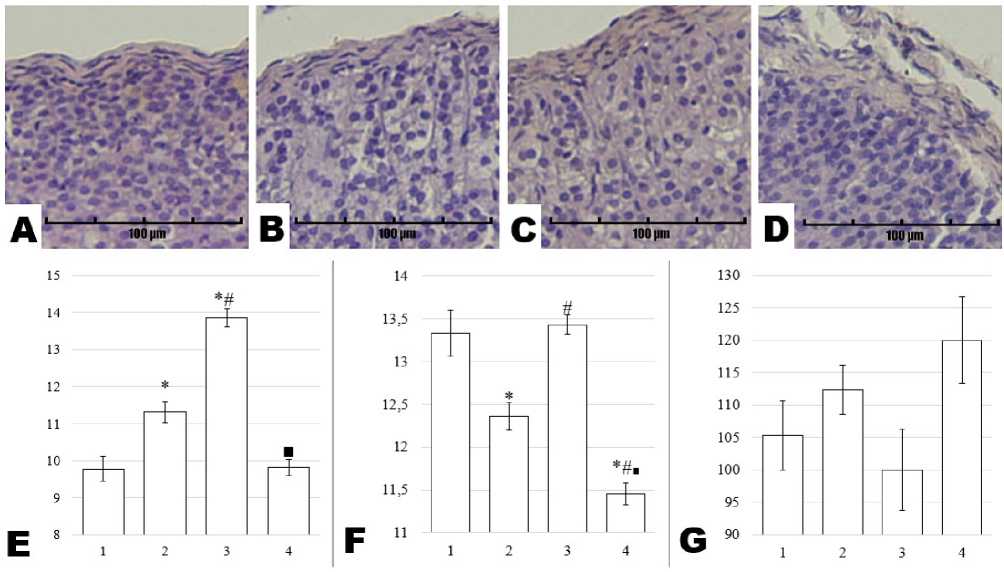

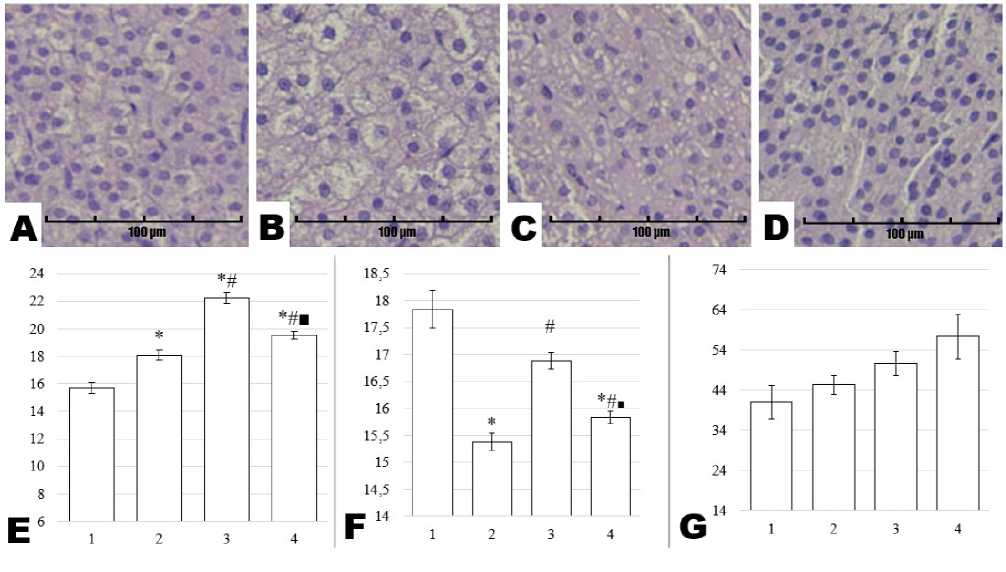

In the fasciculate zone, the nuclear area of adrenal cortical cells was 15.68 ± 0.38 µm² in the Control group. This parameter was significantly elevated in all experimental groups, reaching 18.10 ± 0.37 µm² (Stress), 22.26 ± 0.41 µm² (Preservatives), and

19.53 ± 0.29 µm² (Stress + Preservatives), respectively (p = 0.001 vs. Control for each). Notably, nuclear area in the Stress group was smaller than in the Preservatives (p = 0.001) and Stress + Preservatives groups (p = 0.034). A further significant difference was identified between the Preservatives and Stress + Preservatives groups (p = 0.001). Nuclear perimeter in the Control group was 17.84 ± 0.34 µm, decreasing significantly in the Stress group (15.39 ± 0.16 µm, p = 0.001 vs. Control) and the Stress + Preservatives group (15.83 ± 0.12 µm, p = 0.001). By contrast, the Preservatives group exhibited a perimeter of 16.88 ± 0.16 µm, which did not differ from Control (p = 0.083). Comparisons across experimental groups showed that nuclear perimeter was significantly lower in Stress vs. Preservatives (p = 0.001) and Stress + Preservatives vs. Preservatives (p = 0.001). The cell density per field of view in the fasciculate zone did not differ significantly among groups. Control animals had a mean of 41.00 ± 4.16 cells per field, whereas the Stress (45.33 ± 2.40, p = 0.866 vs. Control), Preservatives (50.67 ± 2.96, p = 0.375), and Stress + Preservatives (57.33 ± 5.61, p = 0.076) groups showed a nonsignificant upward trend. Representative histological images of the fasciculate zone and the corresponding data are presented in Figure 4.

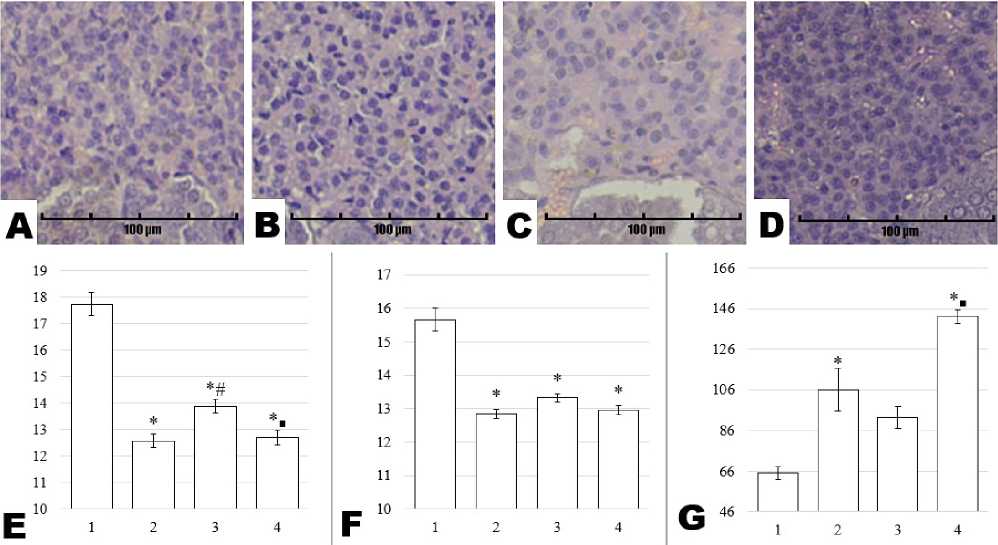

Within the reticular zone, the nuclear area in the Control group measured 17.74 ± 0.43 µm². All experimental groups exhibited significantly lower values

(p = 0.001 vs. Control), reaching 12.57 ± 0.25 µm² in Stress, 13.88 ± 0.25 µm² in Preservatives, and 12.71 ± 0.27 µm² in Stress + Preservatives. Between-group comparisons showed that the Preservatives group had a larger nuclear area than the Stress group (p = 0.003), with no statistical difference between Stress and Stress + Preservatives (p = 0.999). Additionally, nuclear area in Stress + Preservatives was significantly reduced relative to Preservatives alone (p = 0.014). The nuclear perimeter in the Control group reached 15.66 ± 0.33 µm, whereas all experimental groups showed a significant decrease (p = 0.001 vs. Control): 12.85 ± 0.13 µm (Stress), 13.33 ± 0.12 µm (Preservatives), and 12.96 ± 0.14 µm (Stress + Preservatives). No additional differences were found among these experimental groups. In contrast, cell density in the reticular zone was notably higher in all experimental groups compared with Control (65.00 ± 3.06): 106.00 ± 10.41 (Stress), 92.33 ± 5.24 (Preservatives), and 142.00 ± 3.46 (Stress + Preservatives) (p = 0.001 vs. Control for each). Significant distinctions were also identified between Control and Stress (p = 0.007), as well as Control and Stress + Preservatives (p = 0.001). Moreover, the Stress + Preservatives group demonstrated a marked increase in cell density relative to both the Stress (p = 0.015) and Preservatives (p = 0.002) groups. Representative sections from the reticular zone and supporting graphical results are presented in Figure 5.

28 days of exposure

10-12 week-old Male Wistar rats

Group 2. Chronic stress Modeled according to the protocol described by Matisz et al. (2021)

Group 1. Control

Group 4. Food preservatives + chronic stress

Histological examination of the adrenal glands was performed after exposure

Assessment of the adrenal cortex: zona reticular, zona fasciculata, and zona glomerulosa

. Group 3. Food preservatives A single dose of sorbic acid 500 mg/kg b.w. and benzoic acid 100 mg/kg b.w.

Nuclear area, pm2

Nuclear perimeter, pm

Cell density per field of view, units

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the experimental design.

Figure 2. Micrographs of rat adrenal gland sections from the Control (A), Stress (B), Preservatives (C), and Stress + Preservatives (D) groups (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, ×400).

Figure 3. Micrographs of rat adrenal gland sections from the Control (A), Stress (B), Preservatives (C), and Stress + Preservatives (D) groups (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, ×200), alongside morphometric assessments of the glomerulosa zone: nuclear area in µm² (E), nuclear perimeter in µm (F), and cell density per field of view (G). The y-axis represents the numerical value of the measured parameter, while the x-axis shows the experimental groups: Control (1), Stress (2), Preservatives (3), and Stress + Preservatives (4). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference versus Control, a hash (#) versus Stress, and a square (■) versus Preservatives (p < 0.05).

Figure 4. Micrographs of rat adrenal gland sections from the Control (A), Stress (B), Preservatives (C), and Stress + Preservatives (D) groups (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, ×200), alongside morphometric assessments of the reticular zone: nuclear area in µm² (E), nuclear perimeter in µm (F), and cell density per field of view (G). The y-axis represents the numerical value of the measured parameter, while the x-axis shows the experimental groups: Control (1), Stress (2), Preservatives (3), and Stress + Preservatives (4). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference versus Control, a hash (#) versus Stress, and a square (■) versus Preservatives (p < 0.05).

Figure 5. Micrographs of rat adrenal gland sections from the Control (A), Stress (B), Preservatives (C), and Stress + Preservatives (D) groups (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, ×200), alongside morphometric assessments of the fasciculate zone: nuclear area in µm² (E), nuclear perimeter in µm (F), and cell density per field of view (G). The y-axis represents the numerical value of the measured parameter, while the x-axis shows the experimental groups: Control (1), Stress (2), Preservatives (3), and Stress + Preservatives (4). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference versus Control, a hash (#) versus Stress, and a square (■) versus Preservatives (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

During organ dissection, visual inspection, and adrenal mass assessment, we observed no significant alterations attributable to stress, chemical agents, or their combination. Nevertheless, we initially hypothesized that the adrenal glands might undergo hypertrophy under chronic stress an adaptation mechanism previously reported in the literature (Berger et al., 2019; Adzic et al., 2009). In our experiment, however, adrenal mass in the chronically stressed group did not differ from control values, suggesting that both the intensity and the duration of stress exposure may have been insufficient to induce overt organ enlargement. Indeed, morphological increases in adrenal size typically require either more prolonged activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis or more intense stress stimuli (Berger et al., 2019; Adzic et al., 2009; Karin et al., 2020).

Literature suggests that under stress conditions, the fasciculate zone — responsible for glucocorticoid production — bears the greatest functional load. Nevertheless, the glomerulosa zone may also respond indirectly to prolonged stress by helping maintain blood pressure through mineralocorticoid production (Leng et al., 2021; Seidel et al., 2016; Gabai et al., 2020), a vital process for sustaining homeostasis under chronic adverse factors. In the present study, cytoplasmic vacuolization in the glomerulosa zone was noted in the Stress group, alongside an increased nuclear area compared with controls (Holst et al., 2004), which may indicate heightened steroidogenic activity. In contrast, animals receiving only preservatives displayed intact histological organization in the glomerulosa zone, with no evidence of intercellular edema, inflammation, or nuclear enlargement, suggesting minimal functional load in this zone. In the Stress + Preservatives group, nuclear area was significantly lower than in Preservatives alone (p = 0.001), potentially reflecting destructive changes caused by chronic stress. Nuclear perimeter decreased in both the Stress (p = 0.001) and Stress + Preservatives (p = 0.001) groups, yet remained unchanged in Preservatives only, indicating that cells were more resilient to isolated chemical exposure. Cell density in the glomerulosa zone did not differ significantly among groups, suggesting that compensatory proliferation was not triggered within the parameters of this protocol or that the glomerulosa zone exhibits a degree of inherent stability.

The fasciculate zone, as the principal source of glucocorticoids, is particularly sensitive to physiological and pharmacological stressors. Acute stress triggers transient elevations in cortisol or corticosterone levels, whereas chronic exposure may lead to cellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia (Seidel et al., 2016). In the Stress group, we observed cytoplasmic vacuolization in the fasciculate zone: cells appeared lighter owing to the accumulation of lipid droplets, presumably related to intensified corticosteroid secretion. Morphometric analysis revealed that in the Stress group, nuclear area increased while perimeter decreased, implying chromatin or nuclear envelope remodeling (Areshidze et al., 2022). In the Preservatives group, nuclear area was maximally elevated, whereas perimeter remained unchanged, possibly reflecting enhanced corticosteroid synthesis in response to preservative exposure as a form of nonspecific toxic stress. In the Stress + Preservatives group, nuclear area was lower than in Preservatives alone but higher than in Stress, suggesting an additive or synergistic interplay of these factors. The concurrent decrease in nuclear perimeter alongside an increased nuclear area may signify modified functional activity. Cell density in the fasciculate zone remained statistically equivalent to control values in all groups, although we noted a slight upward trend in the combined-exposure group (p = 0.076).

Much attention has been paid to cortisol and other hormones produced in the fasciculate zone due to their roles in energy mobilization and homeostatic maintenance under stress. At the same time, dehydroepiandrosterone and androstenedione — synthesized in the reticular zone — can also modulate overall organismal resilience (Leng et al., 2021). In our study, the reticular zone showed the most pronounced degenerative changes: all experimental groups exhibited marked reductions in nuclear area and perimeter, consistent with diminished functional capacity and potential cellular atrophy. However, in the Preservatives group, nuclear area exceeded that in the Stress group (p = 0.003), indicating comparatively less damage under isolated preservative treatment. Nuclear perimeter likewise decreased in all groups (p = 0.001), pointing to ongoing destructive processes. Cell density, on the other hand, increased substantially across the experimental groups, especially in the Stress + Preservatives group (p = 0.001 vs. Control). The coexistence of degenerative and hyperplastic features suggests a dynamic tissue-remodeling process in which damage and regeneration occur simultaneously. Significant differences between Stress and Stress + Preservatives (p = 0.015), as well as between Preservatives and Stress + Preservatives (p = 0.002), support the notion of reinforced regenerative capacity under combined exposure.

Taken together, this histomorphological assessment of the adrenal cortex demonstrates that both chronic stress and food preservatives induce marked morphological alterations, with the most profound changes arising from their combination. The fasciculate and reticular zones proved particularly vulnerable, showing evidence of both cellular damage and compensatory proliferation. These findings highlight a potential risk of additive endocrine disruption when psychological stress is paired with high-dose dietary preservatives, underlining the need for more comprehensive investigations in stress-related toxicology. Nonetheless, our study faces certain limitations — namely, the absence of hormonal data, which restricts the functional interpretation of the observed morphological changes. Furthermore, although morphometric indices are diagnostically valuable, they warrant additional validation via analyses of steroidogenic enzyme expression and markers of apoptosis or oxidative stress. Such work offers a promising avenue for future research.

CONCLUSION

Chronic exposure to stress and high doses of preservatives (single daily doses of 500 mg/kg sorbic acid and 100 mg/kg benzoic acid) over a 28-day period produced distinct morphological changes in the adrenal cortex of male rats, with the most pronounced effects arising from their combined action. The fasciculate and reticular zones proved especially vulnerable, simultaneously exhibiting both destructive and compensatory processes. These findings underscore the potential risk of additive endocrine disruption when psychological stress coincides with high-dose preservative intake and highlight the need for further comprehensive investigations. In particular, evaluating hormonal status (corticosterone, aldosterone), steroidogenic enzyme expression, and apoptosis markers will be crucial for a more complete understanding of the mechanisms and long-term consequences of such exposure.

Author contribution

Conceptualization, Project administration: D.O. Karimov, Yu.V. Ryabova

Writing – original draft: Yu.V. Ryabova, A.A. Gizatullina, A.O. Khmel

Investigation: Yu.V. Ryabova, A.A. Gizatullina, A.O. Khmel, G.F. Mukhammadiyeva, D. A. Smolyankin, E.F. Repina, M.V. Kurilov

Visualization: Yu.V. Ryabova, A.O. Khmel

Validation, Formal analysis: A.A. Gizatullina, Yu.V. Ryabova, D.O. Karimov

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.