Specifics of external migration into the Pskov oblast

Автор: Vasilenko Pavel Vladimirovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 3 (33) т.7, 2014 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Modern scientists consider migration to be a tool that makes it possible to redistribute human capital, which is currently the most important resource. At that, of special interest are the peripheral regions of the country, including those with the cross-border status, where the influence of migration processes on the structure of population is most noticeable. The Pskov Oblast is currently the leader in Russia in terms of depopulation. Natural decline in the region’s population is only partially compensated by migration. In this regard, the role of migration in the solution of demographic issues of regional development is becoming more and more important. The article presents the analysis of migration processes in the Pskov Oblast in the post-Soviet period; the analysis is based on the processing of statistical data. The author attempts to explain the main trends in migration processes in the framework of the Pskov Oblast for the last 20 years. Informational base of the research is formed by the materials of Pskovstat. The research findings can be used in the drafting and adjustment of a concept for demographic development of the region.

Pskov oblast, demographic crisis, depopulation, migration, external migration, migration balance, migration gain, cis countries

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223589

IDR: 147223589 | УДК: 314.7 | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2014.3.33.8

Текст научной статьи Specifics of external migration into the Pskov oblast

The Pskov Oblast population has been steadily declining since the oblast acquired modern borders (1957). Transcendence of death rate over birth rate was recorded in the region a quarter of a century earlier than on average in Russia [5]. During the last two decades the Pskov Oblast beyond any doubt takes up the top position according to the death rate and natural decline in population [7]. Due to the pessimistic predictive scenario, while keeping up the pace of depopulation outlined in the late 20th century – at the beginning of the 21st century, the population of the Pskov Oblast, having 661.5 thousand people in 2013 could decrease by 150 thousand people in twenty years, i.e. almost by a quarter. Population of the Pskov Oblast comprises 1/215 (0.46%) of the country’s population with density index higher than national average (2012). In the regions ranking according to the value of population the Pskov Oblast lost three points during the last twenty years and took 66th position in 2012. From 1990 the share of the region in the country’s population reduced from 1/175 to 1/215. Fractional data interpretation is used by the author to estimate indicators objectively and proportionally and to define sufficiency extent, in particular, external migration figures.

In the demographic structure the share of people older than working age comprises more than a quarter of the region’s population (about one third in the rural area) and continues to grow, that influences the increase of death rate. Alongside with high death rate among the people of working age and low birth rate, it forms natural decline in population. The share of migration in the structure of increase (decrease) in population of the region is growing.

Nowadays migration outflow to the metropolitan areas is compensated by inflow of migrants from foreign countries, consequently the migration balance comes up to zero. Since 1990 the negative balance has been observed, which is based on the results of seven years (2001, 2005–2010), but common balance has comprised +56.9 thousand people, which nevertheless could not overlap natural decline in population. Maximum figures of arrival were observed in the periods of 1990–1996 and 2011–2012;

however, maximum balance over the whole period belonged to the first interval. It is associated with forced migration of the first half of 1990s mainly from the former republics of the USSR (further from the CIS and Baltic countries). The peak year of 1994 is worth mentioning, when the common migration balance coincides in fact with the number of people migrated from the foreign countries in the current year.

Among the territorial entities of the Russian Federation the region takes 53rd place according to the total number of migrants from the foreign countries arrived during the last twenty years. In that period migrants from the CIS and Baltic countries as well as from Georgia comprised on average 95% of migration inflow to Russia. Neighboring countries with the Pskov Oblast – the Baltic states and Belarus – are able to give far less migrants than Kazakhstan and countries from Central Asia, that based the migration population increase in Povolzhye and Kazakh border zone. Moreover, for the Baltic countries, which are the EU member-states, “west drift” is essential as well as for the whole former Soviet republics, therefore the center of attraction for them is situated the other way round from Russia. If we rank regions, which are neighbored by other countries on land according to the same indicator, the Pskov Oblast will take 23rd place of 38, which is proportional to the common ranking. If we look at the region from the point of view of population size, not from the viewpoint of location, able to provide migration attraction, the region is behind 65 regions out of 83.

Figure 1. Number of foreign migrants per 10 thousand people

Number of arrived foreign immigrants per 10 000 inhabitants of the Pskov Oblast

Number of arrived foreign immigrants per 10 000 inhabitants of Russia

Source: Pskovstat data.

So far as population size of the Pskov Oblast in absolute terms has been rapidly decreasing during the last 50 years, it is better to use for analysis the relative indicator of the foreign migrants per 10 thousand people of the region’s population in a year (fig. 1) .

In the peak year of 1994 according to that indicator the Pskov Oblast took the 11th place (with the indicator 148 people/10 thousand people) after the Magadan Oblast and the Smolensk Oblast, but before Povolzhye and the metropolitan areas; among the cross-border regions – the 5 place, ahead of the Kursk Oblast and the Voronezh Oblast, but conceding the Kaliningrad Oblast and the Belgorod Oblast. In 2011–2012 the region got into the third decade according to the number of foreign migrants per 10 thousand people (the 9th and 12th places among the crossborder regions, respectively), owing to insignificant increase of migrants, as well as the decrease of population. The average value of indicator from 1993 till 2012 comprises 38 people/10 thousand people in the Pskov Oblast, and it takes the 22nd place in the common ranking and the 12th place in the cross-regions ranking.

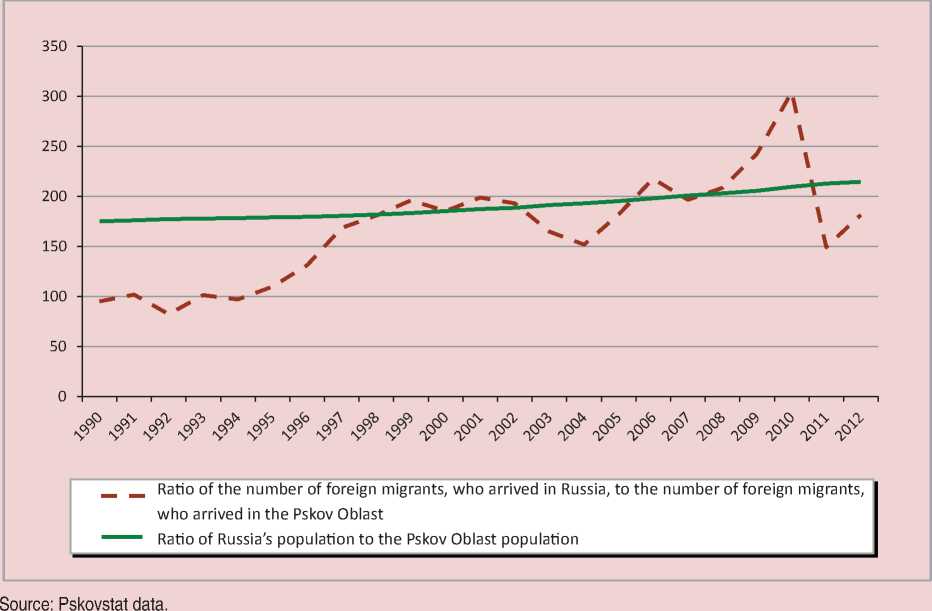

On the figure 2 there is a graph revealing two functions: proportion of the number of foreign migrants arrived in Russia to the number of those who arrived in the Pskov Oblast; and proportion of Russia’s population size to the number of inhabitants of the Pskov Oblast.

Figure 2. Proportion of the number of foreign migrants arrived in Russia to the number of those who arrived in the Pskov Oblast; and proportion of Russia’s population size to the number of inhabitants of the Pskov Oblast

For instance, in 2000 the Pskov Oblast, population of which comprises 1/185 of Russia’s population, was chosen by share of 1/185 from the total number of foreign migrants. Approximately the same values were in 1998 and 2007 – 1/182 and 1/181, 1/201 and 1/197, respectively. Maximum values of indicators correlation were observed in the period up to 1994 – the peak year for external migration to Russia. By that period the tendency regarding return of Russian-speaking population from the former Soviet republics to Russia that began long before the break-up of the USSR still remained. Absolute maximum within 23 years was evidenced in 1992

(1/83), just after the collapse of the USSR. Then the cross-border position of the Pskov Oblast had an impact on the relatively large number of migrants. Correlation of indicators had evened by 1998, when the forced migrations remarkably reduced. Further hesitation of indicator occurred in the range from 1/152 in 2004, which is higher than correlation of population of the Pskov Oblast and Russia in this year, to absolute minimum 1/304 in post-crisis year of 2010, which corresponded the minimum of people arrived in Russia, and apparently, enhancing role of economic factors.

Therefore, the share of migrants in the total number of Russia’s foreign migrants, selected the Pskov Oblast, since 1990 was changing from 1/83 to 1/304, and the share of region in the population of Russia, as mentioned above, reduced from 1/175 to 1/215. Moreover, as the graph shows, trend lines of indicators are co-directional, but the graph of the share of people moved to the territory of the Pskov Oblast in the total number of those, who arrived in Russia, hovers around population function. All in all, if we take into consideration the structure of flow, then it corresponds the gravitation law of migration, according to which the intensity of migration flow is in direct proportion to disparity in the number of population of the arrival and departure points, and inversely proportional to distance between them [2]. Notwithstanding that the invention and widespread use of the gravitation law of migration refers to the middle of the 20th century, the model is used in the analysis of the modern migration processes [1, 8]. In the 1990s the Pskov Oblast, turned out to be in close proximity with contributing countries, took the highest number of migrants (small distance showed up). Then the flow from the western neighboring countries balanced with the flow from the Central Asia countries and on the share of the region fell out its own “quota”, corresponding to the number of the

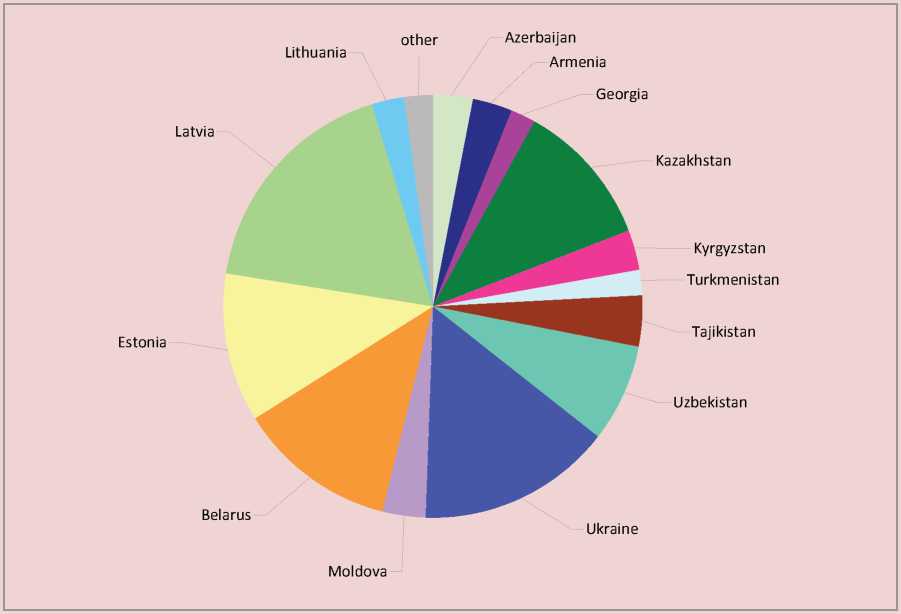

Figure 3. Total structure of foreign migration of the Pskov Oblast in 1990-2011 according to departure countries

Source: Pskovstat data.

region’s population. During the last years, when the migrants from the Central Asia start to predominate, again the small distance showed up (significant remoteness from the departure point), as the result the region lacks migrants (although economic factors and new peculiarities of migration registration interfere, consequently the situation does not look so unambiguous).

Let us consider the structure of foreign migration of the Pskov Oblast during 1990– 2011 according to departure count-ries (fig. 3) . In the investigation period the share of the CIS and Baltic countries, as well as Georgia in this structure comprised 97.7%. Let us divide these countries into four groups: the Baltic states (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia), Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine, the Trans-Caucasian states (Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia) and the Central Asia countries (Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan).

Around one third of arrived migrants (32.4%) came from the Baltic states; that group took the first place among the contributing countries to the Pskov Oblast since 1990. Such indicator was determined by the high share of newcomers from Latvia (18.3%) and Estonia (11.8%), in consequence of mass migrations of the first half of the 1990s, when the arrival of the Russian-speaking population from the Baltic states started. The share of Lithuania was not significant (2.4%). The Pskov Oblast has a common border with Estonia, but historically the region is closely connected with its western neighbors not only by common border, but by population as well. The Russian-speaking population in the Baltic states remains numerous – 29.5% of Latvia’s population, 25.5% of Estonia’s population, and 5.8% of Lithuania’s population, according to the population census of 2011.

Moreover, the Russian-speaking diaspora in Latvia is the biggest one due to the number of Russians per its one resident. Every third resident of the border areas of the Pskov Oblast has relatives across the border in Estonia and Latvia [6].

Regardless of close relationship and high potential of diaspora, mass migration from the Baltic states stopped in the second half of the 1990s. On the one hand, the common peak of migrations of the Russian-speaking population to Russia passed by that time, and that corresponded to the common tendency (everybody, who wanted to leave immediately, left). On the other hand, in the end of 1995 the Baltic states applied for accession to the European Union, and new prospects marked out for residents from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Socio-economic inequality started to grow. Due to reduction of potential migrants, the migration flow ran down. For Estonia and Latvia that category included, first of all, stateless persons, the number of those significantly reduced, and many of them entered preretirement and retirement age, when the possibility of migration declined. Children, born after republics became independent, received citizenship (partly holding parents in place) and now, being the EU citizens, did not connect their future with Russia. For migrants from Latvia both to the Pskov Oblast, and to Russia at large, decrease of indicator was characteristic during 2002– 2008. It was noteworthy that in Latvia in that period there was a special body – Secretariat of the Minister on special commissions on common integration affairs. It was aimed at conducting a dialogue between government and ethnic minorities of Latvia (including Russians), struggling with discrimination, solving existing problems, contributing to creation of society with single value system, etc. Activities of secretariat came under constant criticism, and in 2008 it ceased to exist. After that migration outflow from Latvia to the Pskov Oblast increased again. It was worth mentioning that the program on contributing voluntary resettlement of nationals applied to the residents from the Baltic states as well.

The share of migrants from the Baltic states arrived in the Pskov Oblast in the amount of people arrived in Russia was high – on average 1/27 for the period 1993–2011. Maximum figures were observed for Estonia till 1998 – more than 1/10 of all migrants from that country settled in the Pskov Oblast. Similar figures in that period were observed in Latvia (around 1/10). Further the insignificant hesitation of indicator for both countries was under way (up to 1/20). The share of migrants from Lithuania, selected the Pskov Oblast, was maximum in 2007 – 1/28 and minimum in 2010 – 1/217, having the average value 1/57. For the region accumulating 1/191 of all Russia’s population, those indicators were high and were determined by neighborhood with those countries. Let us consider the distribution of average value concerning the number of migrants arrived from the Baltic states per 10 thousand people in the line Pskov – Moscow, with distance from the border. The highest value was observed in the Pskov Oblast – 11.6 people per 10 thousand people. The next were the Novgorod Oblast and the Smolensk Oblast – 4.6 people and 3.1 people per 10 thousand people, respectively. It was interesting that correlation of indicators of those regions was proportional to correlation of distance from Riga to Veliky Novgorod and from Riga to Smolensk. The closing regions were the Tver Oblast – 2.7 people per 10 thousand people and the Moscow Oblast along with Moscow, the low indicator of those (0.6 people per 10 thousand people) was determined not only by the remoteness, but large population size of the metropolitan area. Therefore, according to the distance of the Russian territory from the borders, the number of arrived migrants from the Baltic states per 10 thousand people is reducing, i.e. intensity of migration is in direct relationship to distance. The common share of the Baltic states in the migration structure to the Pskov Oblast reduced from 39% (1994) to 17% (2011).

The next group of countries consisting of Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova, in 1990–2011 provided 31.3% of foreign migrants of the Pskov Oblast. The share of people arrived from Ukraine during that period comprised 15.6%, Belarus – 12.3%, Moldova – 3.4%. Migration dynamics of this group differs from migration dynamics of the Baltic states. The peak year is 1990, then by 1992 the downswing was observed (it could be assumed that potential migrants ruminated to move or not). By the landmark year of 1994 there was a new growth. The common number of migrants till 1996 ceded the number of those arrived from the Baltic states, but in 1994 from the Central Asia as well. However, decrease of the common number of migrants in the second half of the 1990s did not turn out to be so rushing as for the Baltic states: since 1998 on average 450 people in one year from Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova were steadily coming to the Pskov Oblast against 180 people in one year from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

In contrast to the Baltic states, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova have more numerous Russian diasporas. The largest diaspora is situated in Ukraine (more than 8 million people, according to the population census of 2001); number of Russians in Belarus is great as well (7.9 million people according to the population census of 2009), 200 000 of Russians live in Moldova (according to the population census of 2004). Notwithstanding that number of Russian diasporas of post-Soviet Lithuania and Moldova are comparable, number of migrants from these countries comprise hundreds from Lithuania and thousands from Moldova. The share of migrants from Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova, selected the Pskov Oblast in the total number of migrants from these three countries, selected Russia during 1993–2011, is low – 1/133. However, inside this group there exist some differences: for Belarus, having the common border with the Pskov Oblast, this indicator equals 1/48. For Ukraine this indicator comprises 1/225, testifying that the Pskov Oblast all in all turned out to be less attractive than “average” region of Russia, though there are fluctuations of correlation. The share of migrants arrived in the Pskov Oblast in the total number of migrants arrived in Russia from Moldova during 1993–2011 equals 1/126 on average, moreover, indicator’s periods of growing smoothly interchange periods of decline. In view of political events in Ukraine at the close of 2013 – at the beginning of 2014 and expected growth of the migration flow, the role of this country as the migration donor including the Pskov Oblast situated over the western borders, increases.

Let us consider distribution of average value of the indicator concerning the number of migrants arrived from Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova per 10 thousand people in the line Bryansk – Saint Petersburg. Here the indicator smoothly decrease from the Bryansk Oblast (17.5 people/10 thousand people), lodged between Belarus and Ukraine, through border regions – the Smolensk Oblast (9.7) and the Pskov Oblast (11.2) to relatively distant the Novgorod Oblast (9.7) and populous St. Petersburg (along with the Leningrad Oblast – 7.7 people/10 thousand people).

According to population size the third group of contributing countries for the Pskov Oblast consists of Central Asia countries. Residents of Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan provided 28% of foreign migration during 1990–2011. Migration dynamics to the Pskov Oblast from Central Asia countries is more stable than dynamics of two previous groups of countries – disparity between minimum and maximum of migrants during the investigation period comprises 3233 people, while for the Baltic states – 5818 people, and for Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova – 4468 people.

In 1994 traditional peak was observed, and then local maximums in the total dynamics were evidenced, when migrants came from the remote republics of the Pskov Oblast. In the common structure of contributing countries Central Asia republics were obviously prevailing in 1998, 2001, 2004, as well as starting from 2009. Among the group of Central Asia countries Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan could be marked, which were leading due to the population size in their region and providing respectively 11 and 8% of the whole foreign migration to the Pskov Oblast during 1990–2011. However, from 2006 the number of migrants from the less successful Uzbekistan started to prevail.

During 1990–2011 22 910 people came to the Pskov Oblast from Central Asia, on average 208 people in a year from each of the five republics. Russian-speaking diasporas of Central Asia are numerous, Kazakhstan with 23% of Russians (around 4 million people) and Uzbekistan (around 1 million people) stand out. Outflow of population from Central Asia republics started in 1970 along with ethnic conflicts of the 1980s–1990s and breakup of the USSR strengthened. At present localization of personnel policy, nationalization of education and emerging role of national languages make Russianspeaking population leave Central Asia. Therefore, migration potential of republics remains high. According to the forecast of M.B. Denisenko and N.V. Mkrtchan [3], in the period till 2030 half of the rest Russianspeaking population of Central Asia, i.e. around 2.5 million people (125 thousand people per year) would move to Russia.

While retaining the tendency of the last five years, it would be around 350 people in a year for the Pskov Oblast.

The share of migrants from Central Asia arrived in the Pskov Oblast in total number of Central Asia’s migrants to Russia during 1993–2011 was not big – 1/264. More indifferent to the Pskov Oblast were former residents of Kazakhstan (1/378) and Uzbekistan (1/269). However, there were local maximums – in 1994 the region was chosen by 1/71 and 1/91 of all migrants of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. After the implementation of the state programme on rendering assistance to voluntary resettlement of nationals living abroad to Russia, the number of migrants from Central Asia increased next larger than migrants from other countries. Regardless of republics’ remoteness from the Pskov Oblast and existence of the Baltic Russianspeaking diasporas with high potential, in the near future it would make Central Asia countries the leaders of the contributing countries to the Pskov Oblast.

Let us consider distribution of average value of the indicator concerning the number of migrants arrived from Central Asia countries per 10 thousand people in the line Orenburg – Pskov. Here dynamics is not so unambiguous in comparison with two previous groups of countries. However, if we do not take into account Moscow and the Moscow Oblast, Mordovia and the Ryazan Oblast, we can say that the indicator decreases from Orenburg, Samara and Ulyanovsk to Tver and Pskov.

The last group of former Soviet republics, influencing the migration picture of the Pskov Oblast, consists of the republics of Transcaucasus. Their share in the total number of migrants during 1990–2011 was not big – 8.3% (6789 people). In dynamics of arrival since 1990 after maximum 1994 there was a long-term decline till growth in 2007 on the threshold of economic crisis. It was interesting that the number of migrants from other CIS countries in those years did not grow or grew slightly.

The Russian-speaking diaspora of Transcaucasus is not great, especially after mass migrations at the beginning of 1990s. Migration movement involves not only Russians, but also representatives of titular nations – according to the population census of 2010 2 million of Azerbaijanians, Armenians and Georgians live in Russia (including around 4 thousand on the territory of the Pskov Oblast), that suppose contact of mighty foreign diasporas with their native countries. However, the Pskov Oblast was not an attractive region for migrants from Transcaucasus – since 1990 it was chosen only by every four-hundredth newcomer from Azerbaijan, Armenia or Georgia.

Due to distribution of average value of the indicator concerning the number of migrants arrived from Transcaucasus countries per 10 thousand people in the line “North Ossetia – the Pskov Oblast”, all the migrants settle evenly along the way and do not reach the Pskov Oblast.

As a conclusion, we can mark that the Pskov Oblast, situated near the border, is attractive in terms of migration. Common migration balance during the last 20 years was positive. Foreign migration was presented generally by people from the post-Soviet republics, besides since 1990 in absolute indicators, almost equally both from the Baltic states, Ukraine, Belarus, due to their territorial closeness, and from Central Asia and in a less degree from Transcaucasus and Moldova. According to the existing tendencies, in the structure of external migration predominance of Central Asia direction and essential decrease of the Baltic direction should be expected in the nearest future. In relation to the political events in Ukraine and the possibility of reinforcement of migration flow to Russia it is necessary to take measures on the level of local authorities for creation of some advantages to redistribute part of the flow in favor of the Pskov Oblast. In the external migration picture of the Pskov Oblast the following peculiarity can be noted: the number of foreign migrants is relatively proportional to the population size of the region and co-directionally fluctuates in time with it. Herewith, there is a link between the intensity of migration and distance, which alongside with the previous remark allow speaking about impact of gravity forces on external migration picture of the region. While making out the conception of the Pskov Oblast it is recommended to pay attention to the expected change in the structure of foreign migration in relation to demographic and political processes in the contributing countries. While solving demographic problems of the Pskov Oblast, in general, special attention should be paid to attraction and adaptation of foreign migrants.

Sited works

-

1. Vasilenko P.V. Application of the Gravity Model for the Analysis of Intraregional Migrations on the Example of the Novgorod and Pskov oblasts. Pskov Journal for Regional Studies , 2013, no.15, pp. 83-90.

-

2. Vlasov M.P., Shimko P.D. Modeling of Economic Processes . Rostov-on-Don: Feniks, 2005. 409 p.

-

3. Denisenko M.B., Mkrtchyan N.V. Migration Potential in Central Asia. Strategy 2020 , 2011, July 14. Available at: strategy2020.rian.ru/load/366063112

-

4. Evdokimov S.I. The Forecast of the Main Demographic Indicators of the Pskov Oblast for the First Third of the 21st Century. Pskov Journal for Regional Studies , 2012, no.14, pp. 67-74.

-

5. Krivulya I.V., Manakov A.G. Depopulation in the Pskov Oblast and the Key Directions of Demographic Policy. Pskov Journal for Regional Studies , 2005, no.1, pp. 57-69.

-

6. Kuveneva T.N., Manakov A.G. Formation of Spatial Identities in the Border Region. Sociological Studies , 2003, no.7, pp. 77-84.

-

7. Manakov A.G., Evdokimov S.I. Population Dynamics, Natural and Migratory Movement of the Pskov Oblast Population (16th century – early 21st century). Bulletin of Pskov State University. Series “Natural, Physical and Mathematical Sciences”, 2012, no.1, pp. 91-103.

-

8. Andrienko Yu., Guriev S. Determinants of Interregional Mobility in Russia: Evidence from Panel Data. William Davidson Working Paper , 2003, p. 7.

Список литературы Specifics of external migration into the Pskov oblast

- Vasilenko P.V. Primenenie gravitatsionnoi modeli dlya analiza vnutrioblastnykh migratsii na primere Novgorodskoi i Pskovskoi oblastei . Pskovskii regionologicheskii zhurnal , 2013, no.15, pp. 83-90.

- Vlasov M.P., Shimko P.D. Modelirovanie ekonomicheskikh protsessov . Rostov-on-Don: Feniks, 2005. 409 p.

- Denisenko M.B., Mkrtchyan N.V. Migratsionnyi potentsial Srednei Azii . Strategiya 2020 , 2011, July 14. Available at: strategy2020.rian.ru/load/366063112

- Evdokimov S.I. Prognoz osnovnykh demograficheskikh pokazatelei Pskovskoi oblasti na pervuyu tret’ XXI veka . Pskovskii regionologicheskii zhurnal , 2012, no.14, pp. 67-74.

- Krivulya I.V., Manakov A.G. Depopulyatsionnye protsessy v Pskovskoi oblasti i klyuchevye napravleniya demograficheskoi politiki . Pskovskii regionologicheskii zhurnal , 2005, no.1, pp. 57-69.

- Kuveneva T.N., Manakov A.G. Formirovanie prostranstvennykh identichnostei v porubezhnom regione . Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya , 2003, no.7, pp. 77-84.

- Manakov A.G., Evdokimov S.I. Dinamika chislennosti, estestvennoe i mekhanicheskoe dvizhenie naseleniya Pskovskogo regiona (XVI -nachalo XXI v.) . Vestnik Pskovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya “Estestvennye i fiziko-matematicheskie nauki” , 2012, no.1, pp. 91-103.

- Andrienko Yu., Guriev S. Determinants of Interregional Mobility in Russia: Evidence from Panel Data. William Davidson Working Paper, 2003, p. 7.