Structural and Functional Characterisation of the Chitinase Gene in Chickpea under Aluminum Stress

Автор: Poonam Vanspati, Bhumi Nath Tripathi

Журнал: Журнал стресс-физиологии и биохимии @jspb

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.21, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Aluminum (Alі⁺) toxicity in acidic soils severely limits chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) productivity by impairing root growth and suppressing defence responses. Chitinases are well studied for antifungal activity, but their role under aluminum stress is largely unknown. We present the first structural and functional characterization of chickpea Chitinase 10 (XP_004494478.1) under Alі⁺ stress using in silico approaches. Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis revealed strong conservation and close relatedness to legumes such as Medicago truncatula and Cajanus cajan. Conserved domain mapping and 3D modeling confirmed a stable GH19 catalytic fold. The protein–protein interaction analysis demonstrated that Chitinase 10 is acting as a central hub in the stress responses, while the molecular docking analysis demonstrated that Feі⁺ attaches strongly to a distant site, while Alі⁺ attached comparatively weakly but destructively to the catalytic site near Lys46, Glu228 and Asp231, inhibiting the activity of the enzyme. Our findings reveal that aluminum disrupts the function of Chitinase 10 by disrupting the catalytic site, disrupting its antifungal mode of action. This mechanistic connection indicates that aluminum toxicity disrupts plant defence and provides structural basis to inform breeding or biotechnological applications to improve aluminum tolerance in chickpea.

Aluminum toxicity, Chitinase 10, Cicer arietinum , Molecular docking, Structural characterization

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143185135

IDR: 143185135

Текст научной статьи Structural and Functional Characterisation of the Chitinase Gene in Chickpea under Aluminum Stress

Chickpeas ( Cicer arietinum L.) are important grain legume crops grown throughout the world in semi-arid and tropical regions. It is valued for its protein content, ability to fix nitrogen, and ability to improve soil fertility. However, chickpeas, like many legumes, encounter challenges to productivity due to several abiotic stresses, with Al³ ⁺ toxicity being a significant limiting factor, especially in acidic soils (pH < 5.5). In acidic soils, Al³ ⁺ that is solubilized can easily be taken up by roots without restrictions, inhibiting cell division, root elongation, nutrient transportation, and inhibiting plant growth and development (Munyaneza et al. , 2024). Plants, especially legumes such as chickpeas, have shallow root systems that are more prone to aluminum injury, oxidative stress, and inhibition of physiological and biochemical processes, including nitrogen fixation (Choudhury & Sharma, 2014). However, plants use several detoxification and defence mechanisms, including chelation, compartmentalization, and stress-responsive genes, to respond to biotic and abiotic stress, such as the overexpression of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins.

Chitinases (EC 3.2.1.14) are an important class of PR proteins that contribute to plant defence primarily by hydrolyzing β-1,4-glycosidic bonds from chitin, which is a primary component of the cell walls of fungi and insect exoskeletons. In plants, GH chitinases that act on glycosidic bonds, such as chitin-forming enzymes, are primarily found in the GH18 and GH19 glycoside hydrolase families, with the majority belonging to GH19. In GH19, some class I and class II phytochemicals are commonly reported in higher plants (Panicker & Sayyed, 2022). Chitinases have primarily been documented for their antifungal action, and more research is being conducted on their involvement in abiotic stress, such as drought, salinity, heavy metal toxicity, and aluminum exposure (Sabir et al., 2025). Using transcriptomic and proteomic approaches, chitinase genes have been shown to be upregulated in the early response to abiotic stress, particularly in response to aluminum toxicity. This upregulation suggests a functional role in reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification, membrane stabilization, and cross-signaling during stress conditions, such as copper and iron toxicity and excess metal exposure. Notably, certain chitinases are implicated in both abiotic and biotic (e.g., fungal) stress responses, highlighting their dual role in plant defence mechanisms (Mészáros et al., 2014; Kusunoki et al., 2018; Ranjan et al., 2021). However, the molecular aspects of this interaction under abiotic stress are still not very clear, particularly in legumes such as chickpeas. The actual structural-functional characterization of chitinases with aluminum toxicity has only recently been reported. Notably, metal-protein interactions can add an additional layer of complexity to enzyme structure and function by either stabilizing or inactivating their catalytic activity. aluminum can bind both ionic and negatively charged residues while displacing catalytic metals (for example, Fe²⁺). This displacement potentially changes the active site conformation and prevents normal functionality. (Dudev et al., 2018). Identifying the structural basis for these types of interactions is necessary to understand how chitin-RHO-mediated defence is impacted under aluminum stressThis study provides a structural and functional in silico study of Chitinase 10 gene from Cicer arietinum ( P_004494478.1), which involved sequence verification using BLAST and comparative analysis across legumes, generating multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic investigations, identification of conserved domains, and structural modelling, development of protein-protein interaction networks, and homology-based molecular docking with Al³⁺ and Fe³⁺ ligands. Whether used alone or in combination, provides understanding of structural stability, evolutionary variability, and potential for disruption with aluminum binding, thereby helping to understand the molecular basis which underpins susceptibility or adaptation capacity of this key defensive gene in legumes under aluminum stress.

METHODOLOGY

Sequence Validation and Retrieval

To verify the identity of Al³⁺ stress-responsive genes in chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), the nucleotide sequences of chitinase were examined using the NCBI BLASTn and BLASTx tools .

BLASTn confirmed nucleotide homology, and BLASTx confirmed the translated protein identity. When identities were confirmed, full-length protein sequences for these genes were retrieved from the NCBI Protein Database for chickpeas and eight other legumes ( Glycine max, Medicago truncatula, Phaseolus vulgaris, Vigna radiata, Vigna unguiculata, Cajanus cajan, Lens culinaris, and Pisum sativum ).

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis of Chitinase Protein

To assess the evolutionary conservation/ convergence of the chitinase protein, we obtained fulllength amino acid sequences from Cicer arietinum and other legumes from the NCBI database. All aligned sequences were then input into the Constraint-Based Multiple Alignment Tool (COBALT) on the NCBI website . Using this alignment, we identified conserved motifs and functional domains shared by chitinase proteins in different legumes. Next, we constructed a phylogenetic tree based on sequence similarity using the COBALT Phylogenetic Tree tool. To enhance visual fidelity and improve the ability to make comparisons, we exported the tree from the COBALT tree tool and loaded it into the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) web tool . We were able to examine, within this phylogenetic tree, where chitinase from Cicer arietinum is evolutionarily positioned among its homologous proteins in other legumes, which may reveal its likely functional conservation under the influence of aluminum stress.

Global Protein Alignment and Similarity Analysis

Pairwise global alignments were performed using the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm in EMBOSS Needle . Global alignments produced quantitative metrics, including percentage identity, similarity, and gap percentages, between chickpea proteins and their orthologs from other legumes.

Conserved Domain Identification

To identify any functionally important and evolutionarily conserved sequences in the proteins, the sequences were submitted to the NCBI Conserved

Domain Database (CDD) using the CD-Search Tool , and the domains were mapped and annotated based on known functional motifs and families.

3D Structure Prediction

The 3D structures of the chitinase protein were predicted using the SWISS-MODEL server . These were homology models based on template sequences, and the predicted structures were assessed using QMEAN scores and Ramachandran plots. In cases where high-confidence models were produced, predicted structures developed from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database were also included.

Molecular Docking Studies

To assess metal–protein interactions in the context of Aluminum stress, molecular docking simulations were performed between Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 protein and the metal ions Aluminum (Al³ ⁺ ) and iron (Fe² ⁺ ) using PyRx v0.8 and the docking engine AutoDock Vina. The three-dimensional structure of Chitinase 10 was predicted using SWISS-MODEL

with a homology model based on the closest related plant chitinase templates. The metal ion ligands (Al³⁺ and Fe²⁺) were acquired from the PubChem database.

sdf format, which was converted to. pdbqt format and energy minimized to confirm the geometrically optimized structures. The protein model was also processed before docking in PyRx, which included the addition of hydrogen atoms, assignment of Gasteiger charges, and geometry optimization. The docking simulations aimed to explore binding affinities (kcal/mol) and identify amino acid residues that were sensitive to metal ion docking, especially in the active site and conserved catalytic regions. The final docking outputs were visualized and characterized using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer, where interaction profiles, binding conformations, and structural implications were examined. The emphasis was placed on the differences in binding energy and fit between Al³⁺ and Fe²⁺, to determine whether aluminum could inhibit iron-dependent enzymatic activity or alter chitinase functionality during aluminum stress.

RESULTS

Sequence Confirmation via BLASTn and BLASTx

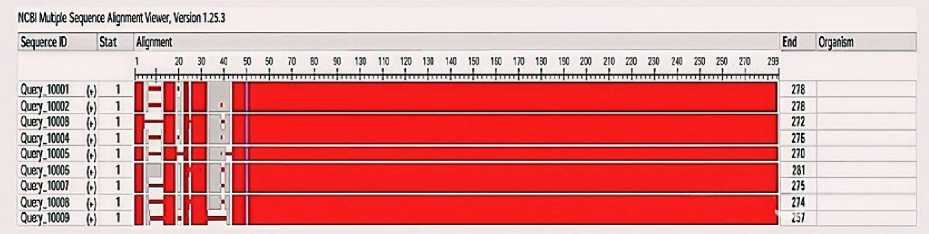

To confirm the identity of the cloned Chitinase gene from Cicer arietinum , the nucleotide and translated protein sequences were compared to known sequences using NCBI BLASTn and BLASTx. This analysis was performed to confirm the evolutionary conservation of the gene and functional annotation before further downstream characterization. The nucleotide sequence was shown ( Fig.1 ) to have a high degree of similarity to previously annotated chitinase genes across several legume species, as well as Cicer arietinum, Glycine max and Phaseolus vulgaris . The best hits had a query coverage of over 95% and strong sequence identity values (85–98%), indicating that the cloned gene was well conserved across legumes.

Following the BLASTn analysis, the translated protein sequence BLASTx results supported these findings by finding the highest alignment with species known to have chitinase proteins. The results indicated very high homology at the protein level, as they indicated conserved glycosyl hydrolase family domains, catalytic residues, and active site motifs generally associated with plant class I or II chitinases. These conserved areas are functionally important and strongly correlated with biotic defence and abiotic stress tolerance, including aluminum detoxification.

Retrieval of Chitinase Protein Sequences from Leguminous Species

After confirming the identity of the cloned chitinase gene from Cicer arietinum, homologous protein sequences were obtained from other leguminous species to conduct comparative structural and evolutionary analyses. Nine species were selected based on agricultural importance, phylogenetic relatedness, and previously reported evidence of agricultural/abiotic stress responses. The nine leguminous species (Table 1) selected were Cicer arietinum, Medicago truncatula, Glycine max, Cajanus cajan, Pisum sativum, Phaseolus vulgaris, Vigna radiata, Vigna unguiculata, and Arachis hypogaea. Full- length protein sequences for Chitinase 10 or the closest homologues were downloaded from the NCBI Protein Database using their respective reference accession numbers. These sequences were used as the basis for multiple sequence alignment, phylogenetic analysis, domain identification, and homology-based structural modeling, which enabled the comparison of sequence conservation and functional domains across species under aluminum stress conditions.

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) for Chitinase Protein Sequences

To evaluate the level of evolutionary conservation and functional similarities in the Chitinase gene in legumes, we carried out Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) using COBALT, a tool offered by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Nine legumes protein sequences were retrieved for the MSA: Cicer arietinum, Glycine max, Medicago truncatula, Cajanus cajan, Pisum sativum, Phaseolus vulgaris, Vigna radiata, Vigna unguiculata, and Arachis hypogaea shown in (Table 2). Through MSA, we detected an abundant amount of sequence conservation, primarily with the central and C-terminal portions of the proteins, assuming roughly amino acid coordinates 40–270. In these parts of the proteins, we were able to align each protein sequence across all species, and they are likely to be structurally and functionally constrained elements, potentially related to catalytic activity. The N-terminal regions (1–40) of the sequence were comparatively more variable, with a limited number of gaps and substitutions shown in (Fig. 2). These variations may be attributed to species-specific divergence, post-translational modifications, or different processing of signal peas. Even with the variation in the regions, we were still able to maintain the structural integrity of our chitinase proteins. Overall, the evidence from the MSAs bolsters the concept of functional conservation of chitinase proteins between legumes, indicating that they can withstand biotic and abiotic stressors, such as Aluminum stress and fungal defence.

Phylogenetic Analysis of Chitinase 10 Proteins

To explore the evolutionary relationships of Chitinase

10 across various leguminous plants, a phylogenetic tree of full-length amino acid sequences obtained from the NCBI Protein Data Bank was constructed. Sequences from Cicer arietinum , Medicago truncatula, Glycine max , Pisum sativum, Phaseolus vulgaris, Cajanus cajan, Vigna radiata, Vigna unguiculata , and Arachis hypogaea were also included in the analysis. The resulting dendrogram illustrated several distinct clades and suggested several lineages. Cicer arietinum clustered closest to Medicago truncatula , indicating high sequence retention and possibly retention of functional similarities in these chitinase proteins, as these two species share a very similar relatedness, indicating a common evolutionary ancestor between the two species or shared conservation of stress-related functional motifs. The second cluster contained Pisum sativum, Phaseolus vulgaris, Vigna radiata , and Vigna unguiculata , indicating a moderate level of evolutionary similarity and that it is possible that chitinase functionality has diversified among these species. In contrast, Cajanus cajan and Arachis hypogaea were more distantly related and formed separate branches, which may be attributed to structural changes or lineage-specific adaptations in the chitinase gene families. The resulting tree topology is similar to the results of the Multiple Sequence Alignment ( Fig. 3 ), and it verifies either conserved or diverged evolutionary trends in leguminous chitinases. These phylogenetic insights offer a clearer understanding of how chitinase genes may have been selected in response to environmental pressures (e.g., aluminum toxicity) and provide insight into functional stability compared to adaptation in different species.

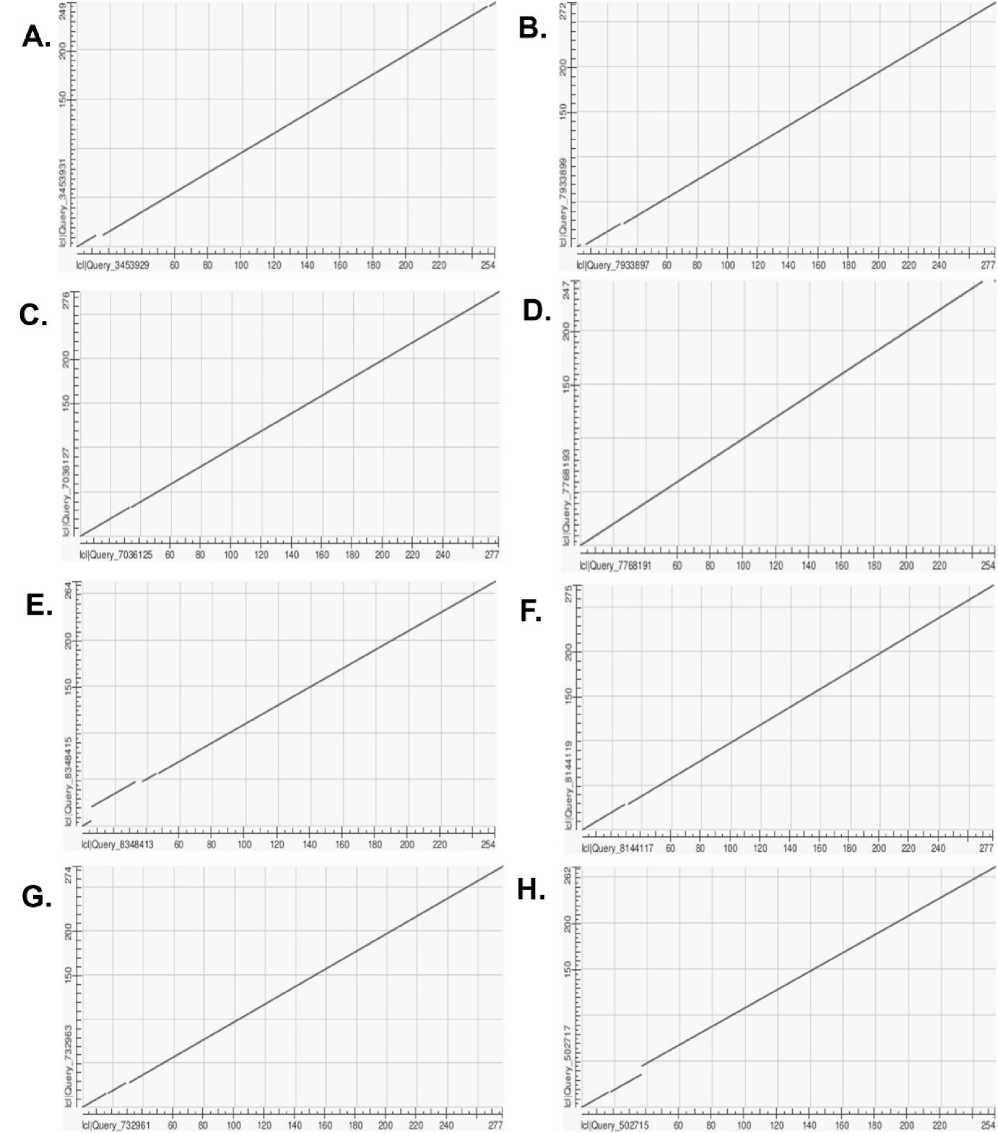

Global Protein Alignment and Dot Plot Analysis

To evaluate the overall structural conservation and sequence homology of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) chitinase 10 proteins with that of other legumes, we conducted several global alignments, specifically pairwise dot plots. We compared the protein sequence of C. arietinum with eight available homologous sequences downloaded from the NCBI Protein Database using EMBOSS Needle and dot plot visualizations. All comparisons represent one-to-one matches, and dot plots indicate the amount of global sequence similarity. The dot plot between Cicer arietinum and Medicago truncatula ( P_003626077.1) produced a nearly perfect linear diagonal (Fig.4A), suggesting very high homology with few insertions or deletions. A strong diagonal was also observed in Glycine max (NP_001276174.1) with equally strong evidence for maintaining the sequence of the primary structure (Fig. 4B). The dot plot with Cajanus cajan ( P_020227974.1) also consistently moved in linear correspondence, again exhibiting a strong sequence similarity (Fig. 4C). The dot plots with Pisum sativum ( P_050917459.1) and Phaseolus vulgaris ( P_068473866.1) both exhibited discernible diagonals (Fig. 4D and 4E), but each was more of a slightly divergent linear form at the start or end, suggesting mild domain variation. The same was true for Vigna radiata ( P_014495374.1) and Vigna unguiculata ( P_027918756.1), with strong alignments and minor shifts in the N-terminus (Fig. 4F and 4G), indicating species-specific processing or adaptation. The alignment with Arachis hypogaea (QHO45167.1) was predominantly linear, but there was slightly more divergence than in the other legumes (Fig. 4H), suggesting possible sequence variation or evolutionary divergence.

The graphical patterns were also validated quantitatively in ( Table 3 ). where the eight legume species returned high match quality (single match), and the amino acid lengths were between 267 and 281 amino acids. Collectively, these results suggest that Chitinase 10 is a highly conserved legume protein that may play a fundamental role in defence and stress responses across legumes.

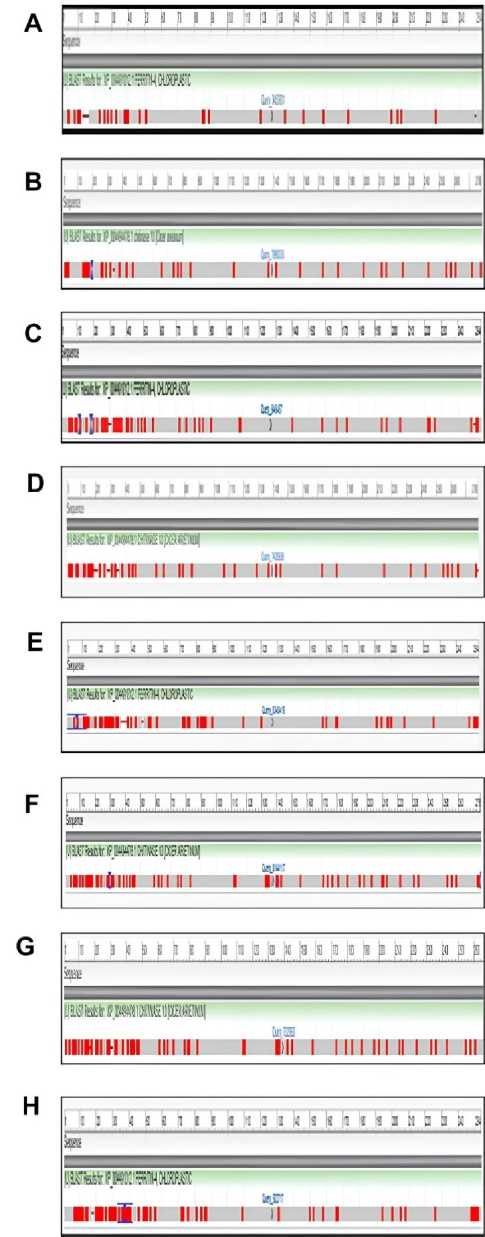

BLAST and Graphical Summary of Global Protein Alignments

Global protein alignments were then performed on the Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 protein to analyze the degree of conservation and evolutionary divergence. Protein alignments were performed using NCBI BLASTp and graphical output of alignments. Eight other homologous protein sequences from legume species were aligned against the chickpea query

P_004494478.1. (Table 4). and presented with graphical red-bar summaries showing areas of conservation for specific amino acid alignment locations. Compared with Medicago truncatula, there was moderate similarity. Areas of conservation were mainly in the N-terminal (residues 1-50) and C-terminal (residues 230-278), suggesting that these regions may contain important catalytic or structural motifs (Fig. 5A). Glycine max again demonstrated partial sequence conservation, with red blocks demonstrating homology primarily close to the terminal regions (Fig. 5B). Cajanus cajan demonstrated the largest conservation across the total protein length. This is shown in the alignment, which has many red bars accumulated and uninterrupted throughout.

Cajanus cajan showed a high level of evolutionary conservation and could offer a closer functional and structural similarity to C. arietinum (Fig. 5C). Alignments of Pisum sativum and Phaseolus vulgaris showed moderate similarities, mostly in the N-terminal and C-terminal domains, and little similarities in the midsequence regions (Fig. 5D and 5E) . This pattern of similarity was probably due to the conserved catalytic cores with diverse flanking sequences. Vigna radiata and Vigna unguiculata showed scattered passengers, but recognizable similarities with moderately strong alignment blocks sandwiched between unconserved regions (Fig. 5F and 5G) . These similarities most likely reflect a common evolutionary ancestor and divergences related to functional changes or evolution along the domain lines. The weakest alignment was observed in Arachis hypogaea , as it only had jagged red bars (Fig. 5H) . This suggests a relatively distant evolutionary relationship and perhaps implies functional divergence primarily in non-conserved specific domains or loop regions of the protein. Overall, the graphical summaries supported the MSA and phylogenetic analyses, confirming the hypotheses by showing that Cajanus cajan shared the most sequence similarity with chickpea Chitinase 10 and that Arachis hypogaea was the most distantly located representative homolog from the other legumes examined.

Conserved Domain Identification of Chitinase 10

To characterize the structural and functional properties of the Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 protein ( P_004494478.1), conserved domain analysis was performed using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) and SPARCLE tools. Conserved domain analysis revealed that the full-length 278 amino acid protein has a chitinase_GH19 domain that has been identified as a specific hit with high confidence, provides very precise functional annotation, and confirms the protein's identity as a chitinase enzyme (Fig. 6). The core domain is present in the majority of the protein length, suggesting that the structural integrity of the catalytic core is retained and highly conserved. The domain fits into two broad superfamilies: the Glyco_hydro_19 superfamily, which contains glycoside hydrolases involved in polysaccharide degradation, and the Lyz-like superfamily, which typically contains defence enzymes, including lysozymes and pathogenesis-related proteins. The domain map also illustrates functionally relevant features, including conserved interactions, such as catalytic residues and sugar-binding residues, which are critical for the enzymatic hydrolysis of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in fungal cell wall chitin. These functional residues were mapped as blue peaks and triangles throughout the primary protein structure, with the more feature-rich region located at approximately amino acid positions 50–230. Not only were there specific confident domain matches, but the protein also showed nonspecific hits to the GH19 (glycoside hydrolase family 19) and Glyco_hydro_19 families, indicating both structural and mechanistic similarities to a large class of plant chitinases. The color-coded domain bars in the analysis show bacterial, invertebrate, plant, and fungal periods, identifying the exact amino acid positions for each domain and showing the exceptional degree of evolutionary conservation for the related functional aspects of the protein.

Thus, this analysis consolidates the notion that Chitinase 10 from Cicer arietinum preserves a closely related catalytic domain architecture required for its biological role as a participant in defence responses. These findings are consistent with the results of multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses and further highlight the importance of this protein in exhibiting stress-induced antifungal activities, perhaps in addition to Aluminum alleviation responses.

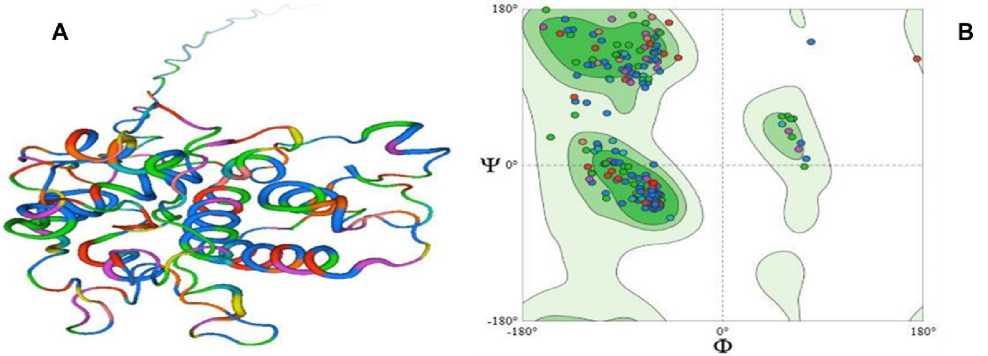

Structural Modelling and Validation

The three-dimensional structure of Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 ( P_004494478.1) was predicted using the SWISS-MODEL homology modeling package. The final constructed 3D structure is shown in (Fig. 7A) it possessed the classic glycosyl hydrolase fold, which consisted of multiple α-helices and β-strands, indicative of plant chitinases. The ribbon diagram highlights a seamless transition from the N- to C-terminus, with the color gradient moving from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus). The structure also verified that there were discrete secondary structural motifs that were organized and aligned as required for the catalytic activity.

The Ramachandran plot (Fig. 7B) from PROCHECK showed that most amino acids were clustered within the allowed and additionally allowed regions, suggesting correct stereochemical geometry. Few residues were in disallowed regions, and they were largely located in the loop regions or terminals, which are notably flexible regions of interaction. These results validate the predicted model while confirming that the protein has been correctly folded and in conformation. This structural validity supports the functional annotation of the protein as an active chitinase, with hydrolysis of chitin via its conserved catalytic core. The structure contains one or more favorable structural features consistent with members of the glycosyl hydrolase family, supporting the presumption that the protein is involved in important functions within plant defence response, especially during stress responses, such as fungal attack or Aluminum pressure to plants.

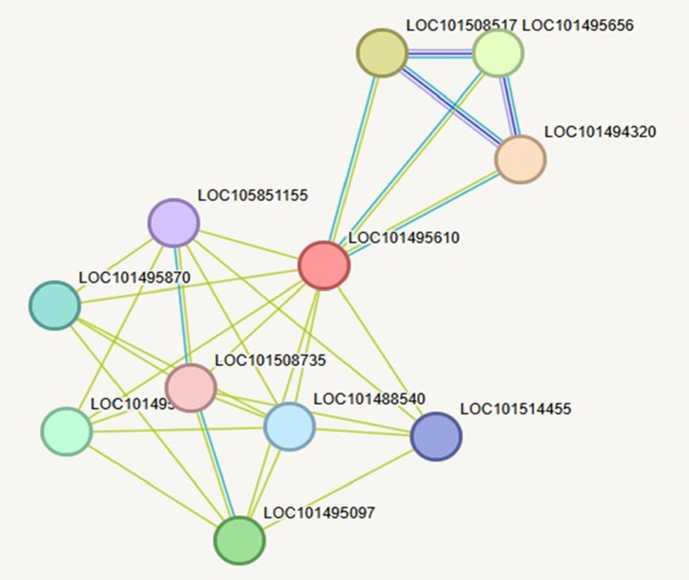

Protein-Protein Interaction Network of Chitinase 10

A protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was built using STRING to provide the contextual function of chitinase 10 (LOC101495610) from Cicer arietinum. STRING uses multiple lines of evidence, including experimental, gene co-expression, text mining, and protein homology data, to build an interaction map. The PPI map indicates that chitinase 10 is a central hub node (Fig. 8). which is associated with a dense cluster of proteins connected to defence- and stress-related functions, such as LOC101495870, LOC101508735, and LOC101495097. This finding indicates a strong potential for co-regulation via stress-induced signalling pathways. The presence of dense and thick edges directing interactions from Chitinase 10 to several partners indicates very high confidence from the STRING score.

In addition, the network has a modular structure in which proteins are grouped into closely related clusters. This is indicative of chitinase 10 acting in multi-protein complexes, possibly in signalling pathways related to immune response and pathogen recognition or antifungal defence. Taken together, the PPI analysis provides strong evidence to support the hypothesis that Chitinase 10 does not act alone but is part of a larger interconnected defence mechanism. Its location as a central hub in the network suggests that it may be a regulatory or catalytic component of the chickpea's defensive response to biotic or abiotic stress.

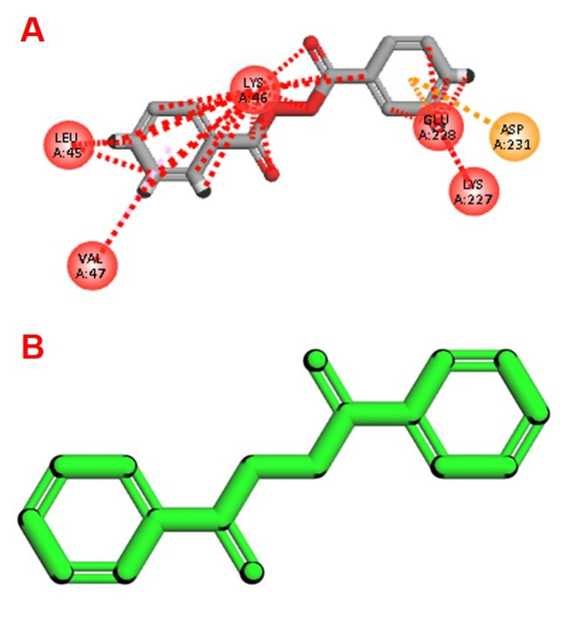

Molecular Docking Analysis of Chitinase with Metal Ligands

Molecular docking analyses were performed to study the interactions of chitinase from Cicer arietinum with aluminum (Al³ ⁺ ) and iron (Fe³ ⁺ ) ligands and the ability to modulate the action of the enzyme.

The docking model with the aluminum ligand (3GWP) indicated a weak binding energy (-5.1 kcal/mol, average binding energy of -4.29 kcal/mol) and posed madory docking poses, demonstrating a greater amount of variability (manoeuvrable positions) which yielded high RMSD values, (up to 55.62 Å). Al³ ⁺ binding was noting nearby catalytic residues (i.e. Lys46, Glu228, Asp231) Shown in (Fig. 9A) illustrating that this association can exist, however, is likely unstable and that the Al³ ⁺ can sterically or chemically inhibit the catalytic core. This indicates a potential inhibitory effect of Al³ ⁺ on chitinase in carrying out its function and therefore possibly compromise the antifungal nature of its defence role under aluminum stress.

The iron ligand (1JS2; ferrioxamine-bound Fe³ ⁺ ) exhibited greater binding affinity (-5.4 kcal/mol, average -4.93 kcal/mol) and significantly better manoeuvrability (≤23.45 Å) suggesting the binding energy is substantially greater and provides a high possibility for stable binding. Fe³ ⁺ was primarily associated with a distal hydrophobic pocket, which may act as structural or stabilizing aid to the overall function of chitinase and substrate chitin

Shown in (Fig. 9B) . The biological relevance of iron association with chitinases is supportive of the notion that functional roles include a redox balance and defence role when conditions are more favourable.

In general, as shown by docking data (Table 5), chitinase likely has a stronger and more stable interaction with Fe³⁺ than with Al³⁺. Aluminum's weak and unstable binding near the catalytic site could render the enzyme inactive, whereas the interaction with Fe³⁺ will likely elicit a physiological effect as chitinase participates in its physiological capacity. This supports the hypothesis that aluminum can indirectly interfere with Fe-dependent physiological defences by inhibiting or altering chitinase activity.

Sequence clone 1 (Chitinase)

>AAGCGTGCAACACACCGCTTTTCGCTCATTTCACGAAACGATACTACACCACTGCACCTGCTGGACCATACACTTGGCCCTTATCA

GTACAATTTGTCCTCAACGTTACTACTGTGTTTCTACTGGCAGACCGCATGTATTGCTTACAAAACTTACATACGTTACGGTCCTATT

CAACTATCTTGGAATTATACCTATGCTCGGAACCCTTCGCATCGTCAGGCTGCGGAATCCAGAGATTGTACCAAACAATTCAGTGCA

TGCTTTCAAAACTGCGACCGGTATTGAGTGGCAGACTCGAAAACCAATTGGTTCCATCACAATGTGTTGGGCATCAATATATTIGTT

ACACAGAGGTGTCATCACAGCTGCTTTTGGATTGGTGTCATATTGTCATGGATTGGAATGTCCAATTCAATGCTGCGTCGTCGACG

AAAAGGATCAAATTCAAAGATATACTCAGTTGTTCAATGTGCGCAAATCCATTTGGAAA

Figure 1. Nucleotide sequence of the cloned Cicer arietinum chitinase gene. The nucleotide sequence was used as the query input for BLASTn and BLASTx analyses to confirm gene identity and establish homology with known chitinase genes from other legume species. The sequence was confirmed to be a chitinase homolog based on the conserved domains and high alignment scores.

Figure 2. Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of the Chitinase 10 proteins from nine legume species. Highly conserved regions are shown in red blocks, and we observed significant alignment in the middle and C-terminal domains. We only observed modest variability, primarily in the first ~40 amino acids. We suspect that the variability in alignment is likely a consequence of species divergence.

Tree scale: 0.1 i-----------------------------------------------1

----------------------------------------------------------►'QHO45167.1 Chitinase'

>'NP 001276174.1 Chitinase 10-like precursor'

--------------- ----------------- ---------------►'XP 068473866.1 chitinase 10-like'

---------------►'XP 014495374.1 chitinase 10 '

---------► XP 027918756.1 chitinase 10-like 1

---------------- ------------------------------►'XP 050917459.1 chitinase 10-like '

------------------------------------►'XP 004494478.1 chitinase 10 '

-----------------------►'XP 003626077.1 chitinase 10 '

-------------------------------►'XP 020227974.1 chitinase 10 '

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree of chitinase 10 protein sequences from nine legumes. The tree was constructed utilizing NCBI COBALT's phylogenetic capability of NCBI COBALT embedded in the program/tool. The close clustering of Cicer arietinum and Medicago truncatula suggests an evolutionarily conserved lineage. Other legumes showed relatedness as groups of Glycine max , Phaseolus vulgaris , Pisum sativum , and Vigna species , whereas Cajanus cajan and Arachis hypogaea maintained a more distant position, suggesting different functional roles.

Figure 4. Dot plot analysis of chickpea chitinase with homologs from ( A ) Medicago truncatula ( P_003626077.1), ( B ) Glycine max (NP_001276174.1), ( C ) Cajanus cajan ( P_020227974.1), ( D ) Pisum sativum ( P_050917459.1), ( E ) Phaseolus vulgaris ( P_068473866.1), ( F ) Vigna radiata ( P_014495374.1), ( G ) Vigna unguiculata ( P_027918756.1), and ( H ) Arachis hypogaea (QHO45167.1). In all comparisons, the continuous diagonals indicate strong sequence conservation and high homology with minimal mismatches.

Figure 5. BLAST and graphical summary of global protein alignments of Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 ( P_004494478.1) with homologs from ( A ) Medicago truncatula (Query_7890333), ( B ) Glycine max (Query_7890333), ( C ) Cajanus cajan (Query_7036125), ( D ) Pisum sativum (Query_7428559), ( E ) Phaseolus vulgaris (Query_7862119), ( F ) Vigna radiata (Query_8144117), ( G ) Vigna unguiculata (Query_732961), and ( H ) Arachis hypogaea (Query_7775611). Conserved regions are represented by red bars, with higher density indicating strong similarity. Alignments highlight conserved N-terminal and C-terminal domains, supporting structural and functional conservation of chitinase across legumes.

Domain families on selected sequences

H-ZOOtn: lx v| View [Full Results

] Show functional sites Q Show SPARCLE info Q

Q#1 - >XP_004494478.1 ((Local ID))

Redundancy

Full Results

Show functional sites ✓ Show SPARCLE info ✓

XP_004494478.1 chitinase 10 [Cicer arietinum]

It#

125 151 175

211 225

27#

Query seq.

catalytic residues sv^ar ЬЫ»1 sita

Specific hits

Non-specific hits

Superfanilies

<

diilmnjHH

SlywJ^.U а» chiliMseliht

Lyz-like superfamily Glyco_hyclro_19 superfamily

Figure 6. Conserved domain architecture of the Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 protein ( P_004494478.1). The black bar represents the full query sequence (1–278 amino acids). The Fig. shows a specific chitinase_GH19 domain (purple), broader non-specific domain matches including Glyco_hydro_19 and GH19 (light blue), and classification under the Lyz-like and Glyco_hydro_19 superfamilies (yellow). Functional sites, including conserved catalytic residues and sugar-binding motifs, are highlighted as blue peaks and triangles, respectively.

Figure 7. Predicted 3D structure and validation of Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 protein. ( A ) Ribbon diagram of the SWISS-MODEL–predicted structure showing α-helices and β-strands with N- to C-terminal progression (blue to red), characteristic of glycosyl hydrolase folds. ( B ) Ramachandran plot assessing stereochemical quality, with most residues located in favored (dark green) and allowed (light green) regions, confirming acceptable backbone geometry and proper folding.

Figure 8. STRING-based protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of chitinase 10 (LOC101495610) in Cicer arietinum . Nodes represent individual proteins (identified by their LOC IDs), and edges denote predicted functional or physical associations. Thicker edges represent stronger evidence and confidence. The network highlights the involvement of chitinase 10 in a defence-related interaction cluster, suggesting functional integration in stress-responsive pathways.

Figure 9. Molecular docking of Cicer arietinum chitinase 10 with metal ions. ( A ) Aluminum (Al³ ⁺ ) binds near the catalytic residues Lys46, Glu228, and Asp231, potentially interfering with the enzymatic activity. ( B ) Iron (Fe² ⁺ ) shows stable binding at a distal site, indicating a less disruptive or possibly structural role for iron.

Table 1- Retrieved Chitinase 10 protein sequences from chickpea and related legumes

|

S. No. |

Organism |

Protein Name |

NCBI Accession Number |

|

1. |

Cicer arietinum |

Chitinase 10 |

P_004494478.1 |

|

2. |

Medicago truncatula |

Chitinase 10 |

P_003626077.1 |

|

3. |

Glycine max |

Chitinase 10-like precursor |

NP_001276174.1 |

|

4. |

Cajanus cajan |

Chitinase 10 |

P_020227974.1 |

|

5. |

Pisum sativum |

Chitinase 10-like |

P_050917459.1 |

|

6. |

Phaseolus vulgaris |

Chitinase 10-like |

P_068473866.1 |

|

7. |

Vigna radiata var. radiata |

Chitinase 10 |

P_014495374.1 |

|

8. |

Vigna unguiculata |

Chitinase 10-like |

P_027918756.1 |

|

9. |

Arachis hypogaea |

Chitinase |

QHO45167.1 |

Table 2- Details of protein sequences used for multiple sequence alignment

|

Accession |

Species Name |

% identity |

|

P_004494478.1 |

Cicer arietinum |

100.00% |

|

P_003626077.1 |

Medicago truncatula |

90.38% |

|

NP_001276174.1 |

Glycine max |

88.89% |

|

P_020227974.1 |

Cajanus cajan |

86.96% |

|

P_050917459.1 |

Pisum sativum |

92.75% |

|

P_068473866.1 |

Phaseolus vulgaris |

87.92% |

|

P_014495374.1 |

Vigna radiata |

87.92% |

|

P_027918756.1 |

Vigna unguiculata |

87.92 |

|

QHO45167.1 |

Arachis hypogaea |

82.44% |

Table 3- Summary of global alignment results for Chitinase 10 protein

|

S. No. |

Protein Accession |

Species |

Sequence ID |

Length (aa) |

Number of Matches |

|

1. |

P_003626077.1 |

Medicago |

Query_7890335 |

278 |

1 |

|

truncatula |

|||||

|

2. |

NP_001276174.1 |

Glycine max |

Query_7933899 |

272 |

1 |

|

3. |

P_020227974.1 |

Cajanus cajan |

Query_7036127 |

276 |

1 |

|

4. |

P_050917459.1 |

Pisum sativum |

Query_7428559 |

270 |

1 |

|

5. |

P_068473866.1 |

Phaseolus vulgaris |

Query_7862121 |

281 |

1 |

|

6. |

P_014495374.1 |

Vigna radiata |

Query_8144119 |

275 |

1 |

|

7. |

P_027918756.1 |

Vigna unguiculata |

Query_732963 |

274 |

1 |

Table 4- Comparative summary of BLAST-based global protein alignments between Cicer arietinum and eight legume species

|

S. No. |

Species |

Sequence Conservation |

Regions with High Similarity |

Evolutionary Relationship |

|

1. |

Medicago truncatula |

Moderate |

N-terminal (1–50), C-terminal (230–278) |

Moderate |

|

2. |

Glycine max |

Low overall |

Some stretches in N- |

Partial functional domain |

|

and C-terminal |

retention |

|||

|

3. |

Cajanus cajan |

High |

Entire sequence |

Close relationship |

|

4. |

Pisum sativum |

Moderate |

Start and end regions |

Functional core conservation |

|

5. |

Phaseolus vulgaris |

High (N-terminal), moderate (rest) |

N-terminal half |

Shared ancestry, diverged regions |

|

6. |

Vigna radiata |

Scattered/moderate |

Conserved residues throughout |

Moderate divergence |

|

7. |

Vigna unguiculata |

Moderately strong |

Multiple aligned blocks across the sequence |

Closer than V. radiata |

|

8. |

Arachis hypogaea |

Limited |

Few and fragmented regions |

Distant relationship |

Table 5 Comparative analysis of docking parameters for chitinase interaction with Aluminum and iron ligands, including binding energy, RMSD, pose stability, and predicted functional implications

|

Parameter |

Aluminum Ligand (3GWP) Iron Ligand (1JS2) |

|

Ligand Type |

Tris (acetylacetonato) Aluminum Ferrioxamine B |

|

Metal Center |

Al³ ⁺ Fe³ ⁺ |

|

PDB Ligand ID |

3GWP 1JS2 |

|

Best Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) |

-5.1 -5.4 |

|

Average Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) Lowest RMSD_lb (Å) Highest RMSD_lb (Å) |

-4.29 -4.93 0.0 0.0 55.62 23.45 |

|

Pose Stability |

Highly variable and unstable More stable and consistent |

|

Biological Implication |

Weak and unstable binding near catalytic Stronger and more specific binding residues; may inhibit enzymatic action in distal pocket; supports Fe-related under Al stress functional stability |

|

Conclusion |

Al³ ⁺ binds weakly and inconsistently, Fe³ ⁺ binds more stably and potentially interfering with catalytic strongly, indicating its natural activity and impairing defence responses association with chitinase and under stress supporting normal enzymatic/structural functions |

DISCUSSION

Chitinases are known to play an important role in plant defence against fungal pathogens via the hydrolysis of chitin in the pathogens' cell walls. Recently, however, a few studies have provided evidence that chitinases perform a more general role in plant responses to abiotic stresses such as aluminium (Al³⁺) toxicity (Langner et al., Göhre, 2016; Pusztahelyi, 2018; Kumar et al., 2018). As a result, we characterized the Chitinase 10 gene from Cicer arietinum ( P_004494478.1) to investigate any structural and functional responses of chitinase10 under Al³⁺ stresses in legumes.

The BLASTn and BLASTx analyses showed Chitinase 10 to be a Class I chitinase with the conserved Glycoside Hydrolase Family 19 (GH19) domain, which is common of plant chitinases that perform roles in antifungal defence and abiotic stress toleration (Wang et al. , 2024; uan et al. 2024; Sabir et al. in press). The phylogenetic analysis grouped C. arietinum Chitinase 10 closely to Medicago truncatula, suggesting conservation of evolutionary history among Anseae, while Cajanus cajan and Arachis hypogaea were grouped separately, suggesting potential evolutionary adaptation specific to those lineages (Ellur, 2022; Narula et al. , 2024).

The analysis of conserved domains confirmed the identification of a GH19 catalytic core corresponding to the Lyz-like superfamily, thus demonstrating the presence of features that were structurally and functionally conserved to better withstand biotic and abiotic strain factors (Fig 6; Orlando et al. , 2021; Bolaños, L. M.). Structural modelling supports the typical glycosyl hydrolase fold and Ramachandran plot analysis would confirm correct stereochemical geometry of angle of rotation and secondary structural arrangement (Fig 7; Yusof et al. , 2017; Dutta et al. , 2021; Bhagwat et al. , 2021; El-Sayed et al. , 2024).

In particular, protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis showed that Chitinase 10 was important in several stress-registered signalling pathways, meaning that it could be co-regulated with other proteins related to defence response pathways (Fig 8; Ashraf et al. , 2018; Razalli et al. , 2025).

Specifically, molecular docking produced effective insights into the nature of the metal–protein interactions in the chickpea Chitinase 10. Aluminium (Al³ ⁺ ) was more weakly bound, yet it was still near the catalytic residues (Lys46, Glu228 or Asp231), hence, it could hinder substrate access, and/or perturbed the catalytic residue and thus the conformation of the active site (Fig 9A). Conversely, iron (Fe³ ⁺ ) was more stably bound to a distal hydrophobic pocket, supporting the suggestion that iron also contributes to structural stabilization and redox balance (Fig 9B). Collectively, these results indicate that

Al³ ⁺ was functioning as competitive inhibitor, displacing and not allowing bound functionally important co-factors like Fe³ ⁺ and impeding enzyme action (Yan et al. , 2022; Hajibolland et al. , 2023; Munyaneza et al. , 2024).

Overall, these results provide a mechanistic connection between Al³ ⁺ toxicity and damaged antifungal defence in legumes. Weak Al³ ⁺ interactions near the catalytic site may inhibit the function of Chitinase 10, causing increased susceptibility to fungal pathogens, as well as increased oxidative stress in acidic soils.

CONCLUSIONS

Chickpea Chitinase 10 is structurally conserved and a pivotal point in defence networks. Molecular docking studies show Fe³ ⁺ binds stably and lend support to enzymatic activity, and that Al³ ⁺ weakly binds near the catalytic residues and could potentially inhibit enzymatic activity. These data reveal a novel mechanism of aluminium toxicity that decreases chitinase-mediated antifungal defence. The mechanistic insights presented here can be utilized for breeding and biotechnological approaches to improve aluminum tolerance in chickpea and related legumes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Department of Biotechnology, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak, Madhya Pradesh, India.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this study.